Abstract

Asenapine is a new second-generation antipsychotic approved in September 2010 by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of bipolar disorder. It demonstrated significant efficacy compared with placebo in acute mania or mixed episodes as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to mood stabilizers (lithium or valproate). Early improvement was noted at day 2 and was strongly associated with response and remission at week 3. Asenapine also appeared effective in treating acute mania in older patients with bipolar disorder. Post hoc analyses of asenapine showed efficacy in treating depressive symptoms during manic or mixed episodes compared with placebo. The efficacy of asenapine in patients with acute mania appeared to remain constant during maintenance treatment. Asenapine was reasonably well tolerated, especially with regard to metabolic effects. There were minimal signs of glucose elevation or lipid changes and the risk of weight gain appeared limited. The prolactin elevation was smaller than other antipsychotic comparators. Only oral hypoesthesia occurred as a new adverse event compared with other second-generation antipsychotics. Asenapine presents several advantages over other second-generation antipsychotics, such as sublingual formulation, early efficacy and good metabolic tolerability. This tolerability profile confirms the heterogeneity of the second-generation antipsychotic class and supports the view of some authors for the need to re-evaluate the boundaries of this group.

Keywords: antipsychotics, asenapine, bipolar disorder, mania

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and common cyclic mood disorder characterized by the occurrence of manic, depressive or mixed episodes. The lifetime prevalence is approximately 1% in Europe [Pini et al. 2005]. Its clinical heterogeneity requires a complex pharmacologic and psychosocial approach. For several decades, lithium, anticonvulsants and first-generation antipsychotic medications have been used in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

More recently, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have emerged in bipolar disorder as an option for the treatment of depressive or manic episodes and for maintenance treatment. In guidelines, these medications are recommended as first-line treatment for mania, and quetiapine or olanzapine as first-line treatment for bipolar depression [Goodwin, 2009; Grunze et al. 2009; Llorca et al. 2010; Malhi et al. 2009; Yatham et al. 2009].

Some SGAs may be somewhat more efficacious or more tolerated than others. Head-to-head comparisons demonstrate that SGAs cannot be considered as a homogeneous group and that current classification of the drugs should probably be revised [Leucht et al. 2009].

Each SGA has a different pharmacodynamic profile and a new compound may have a specific interest, in terms of efficacy or tolerance, for patients with bipolar disorder.

Asenapine is a new SGA approved in August 2009 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and in September 2010 by the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) for the treatment of acute manic episodes in adults with bipolar I disorder. Asenapine is also approved in the USA for the treatment of acute schizophrenia.

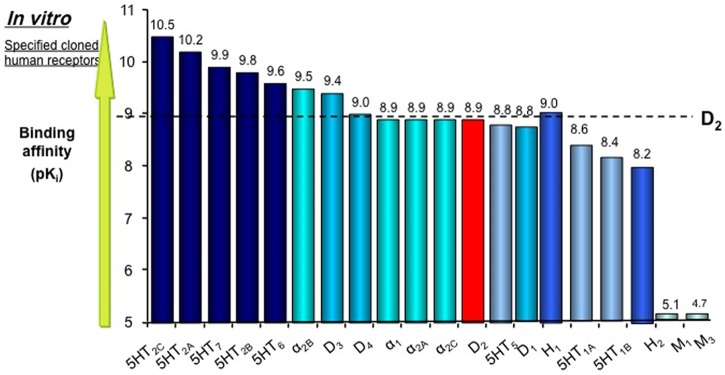

This compound has a mechanism of action mediated through a combination of antagonist activity at 5HT2A and D2 receptors [Shahid et al. 2009]. This antipsychotic also has a high affinity for other receptors, including antagonism at 5HT2B, 5HT2C, 5HT6 and 5HT7 serotoninergic, α1A, α2A, α2B and α2C adrenergic and D3 and D4 dopaminergic receptors (Figure 1). The serotoninergic profile (especially the effect on 5HT7) could justify clinical efficacy for anxiety, mood regulation and cognitive features. Asenapine has no appreciable affinity for muscarinic receptors and induces fewer anticholinergic side effects than other SGAs [Bishara and Taylor, 2009; Elsworth et al. 2012; Hedlund, 2009].

Figure 1.

Receptor binding profile of asenapine. Reproduced with permission from [Shahid et al. 2009].

The aim of this review is to provide an update of current data published about the efficacy and safety of asenapine for the treatment of bipolar disorder. In addition, the specific clinical interest of asenapine in clinical practice will be discussed.

A review of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of asenapine in bipolar disorder has been published in several articles [Bishara and Taylor, 2009; Chwieduk and Scott, 2011; Citrome, 2009; Gonzalez et al. 2011; Henry and Fuller, 2011; McIntyre, 2011; McIntyre and Wong, 2012; Pompili et al. 2011; Samalin et al. 2012; Stoner and Pace, 2012]. This update takes into account recent published studies completed and post hoc analysis of asenapine in patients with bipolar disorder.

Data sources

A literature search using the keywords ‘asenapine‘ and ‘bipolar disorder’ was undertaken using the databases PubMed and EMBASE to find all the relevant studies published. Additional references were identified from http://www.fda.gov, http://www.ema.europa.eu and http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Data were also collected from product user information and congress communications. Searches were last updated on 20 September 2012.

Short-term and long-term monotherapy studies of asenapine in bipolar disorder

Asenapine as monotherapy in the treatment of manic and mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder has been assessed in two short-term randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled studies for 3 weeks [McIntyre et al. 2009a, 2010b] with, for both, an extension study of 9 and 40 weeks [McIntyre et al. 2009b, 2010a]. A small open-label 4-week study, evaluating asenapine as monotherapy in older patients with bipolar mania, has also been conducted [Baruch et al. 2012] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical trials of asenapine in bipolar I disorder.

| Study | Design | Duration (weeks) | Sample | N randomized | Asenapine (± active comparator) |

Results (primary outcomes for short-term studies) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/day) | N (ITT) | ||||||

| Short-term studies | |||||||

| McIntyre et al. [2010b] A7501004 | RCT, DB, PC | 3 | Manic or mixed episodes | 488 | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20 | 183 | −11.5 ± 0.8 (p ≤ 0.01) | |||||

| Olanzapine 5–20 | 203 | −13.3 ± 0.8 (p ≤ 0.0001) | |||||

| Placebo | 94 | −7.8 ± 1.1 | |||||

| McIntyre et al. [2009a] A7501005 | RCT, DB, PC | 3 | Manic or mixed episodes | 488 | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20 | 189 | −10.8 ± 0.8 (p ≤ 0.0001) | |||||

| Olanzapine 5–20 | 188 | −12.6 ± 0.8 (p ≤ 0.0001) | |||||

| Placebo | 103 | −5.5 ± 1.0 | |||||

| McIntyre et al. [2009b] A7501006 | Extension study (subjects who completed A7501004/5 studies), DB | 9 | Manic or mixed episodes | 504 | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20 | 181 | −20.1 ± 10.7 (NS versus olanzapine) | |||||

| Olanzapine 5–20 | |||||||

| Placebo/asenapine | 229 | −21.3 ± 9.6 | |||||

| 94 | |||||||

| Baruch et al. [2012] | Open-label study | 4 | Manic episodes Older patients | - | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20 | 11 | −21.4 ± 12.9 | |||||

| Szegedi et al. [2012] A7501008 | RCT, DB, PC Adjunctive study in patients treated with Li or Val | 12 | Manic or mixed episodes treated with Li or Val | 326 | Least square mean changes in YMRS (week 3 and 12) ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20/Li, Val | 155 | −10.3 ± 0.8 (p = 0.0257); –12.7 ± 0.9 (p = 0.0073) | |||||

| Placebo/Li, Val | 163 | −7.9 ±0.8; –9.3 ±0.9 | |||||

| Long-term studies | |||||||

| McIntyre et al. [2010a] A7501007 | Extension study (subjects who completed A7501004/5/6), DB | 40 | Bipolar I disorder | 218 | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20 | 76 | −25.8 ± 10.3 (NS versus olanzapine) | |||||

| Olanzapine 5–20 | 104 | −26.1 ± 8.4 | |||||

| Placebo/asenapine | 32 | ||||||

| Szegedi et al. [2012] A7501009 | Extension study (subjects who completed A7501008), DB | 40 | Bipolar I disorder | 77 | Least square mean changes in YMRS ± SD (LOCF) | ||

| Asenapine 10–20/Li, Val | 41 | −17.2 ± 13.65 (no statistical analysis) | |||||

| Placebo/Li, Val | 36 | −19.7 ± 11.81 | |||||

DB, double blind; ITT, intention to treat; Li, lithium; LOCF, last observation carried forward; NS, not statistically significant; PC, placebo controlled; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; Val, valproate; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Three-week placebo-controlled studies

The aim of these studies was to demonstrate the superiority of asenapine compared with placebo for 3 weeks in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes [McIntyre et al. 2009a, 2010b]. These randomized double-blind placebo-controlled studies also include an arm with olanzapine as an active control and were identically designed.

Subjects were included when having a current manic or mixed bipolar I episode that must have begun no more than 3 months prior to the screening visit and have a Young-Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score greater than or equal to 20.

A total of 976 patients were randomly assigned to receive asenapine (flexible dose, sublingual, 10 mg twice daily, adjustable to 5 mg), olanzapine (15 mg daily, adjustable to 5–20 mg) or placebo treatment in a 2:2:1 ratio.

The mean total daily doses for asenapine and olanzapine were similar in both studies (A7501004: 18.2 ± 3.1 mg/day and 15.8 ± 2.3 mg/day, A7501005: 18.4 ± 2.7 mg/day and 15.9 ± 2.5 mg/day, respectively).

In the two studies, the evolution of YMRS total scores from baseline to 3 weeks (primary endpoint) were statistically significantly improved in the asenapine and olanzapine arms compared with the placebo arm (p < 0.01). These significant improvements in the YMRS were noted for asenapine and olanzapine from day 2 onwards.

Only one study [McIntyre et al. 2009a] demonstrated a significantly higher rate of responders (p = 0.0049) and remitters (p = 0.002) for asenapine in comparison to placebo.

Nine-week extension study

The aim of this 9-week extension study was to demonstrate the noninferiority of asenapine compared with olanzapine for 12 weeks as a maintenance treatment [McIntyre et al. 2009b].

Subjects treated with active, double-blind therapy were to continue in their initial treatment group (asenapine 5–10 mg twice daily or olanzapine 5–20 mg once daily). Subjects previously treated with placebo were blindly allocated to receive asenapine (5–10 mg twice daily) but they were only included in the safety analyses.

Five hundred and four subjects received at least one dose of trial medication in this extension study (181 subjects treated with asenapine, 229 subjects treated with olanzapine and 94 who had received placebo in the feeder study).

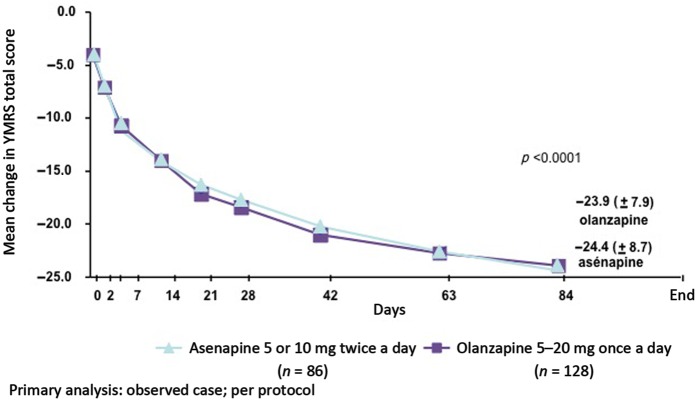

At day 84, the mean change in YMRS from baseline (primary endpoint) was not statistically different in the asenapine and olanzapine groups (Figure 2) and determined the noninferiority of asenapine versus olanzapine. The percentage of YMRS responders and remitters was similar in both groups.

Figure 2.

Mean change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score from baseline to day 84. Reproduced with permission from [McIntyre et al. 2009].

The risk of emergent depressive symptoms was relatively low with asenapine and not substantially different from olanzapine. The percentage of patients shifting their Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores from up to 8 at baseline to at least 16 at endpoint was 2.3% for asenapine-treated patients and 5% for olanzapine-treated patients.

Forty-week extension study

The aim of this 40-week extension study was to assess the safety of asenapine. The secondary analyses were conducted to determine the efficacy of asenapine and olanzapine from baseline to 52 weeks [McIntyre et al. 2010a].

Two hundred and eighteen completers of the 9-week extension study were eligible to enter in the 40-week extension study. The mean changes in YMRS from baseline are presented in Table 1. The responder and remitter rates were not significantly different between asenapine and olanzapine groups.

Four-week open-label study of older patients with bipolar mania

Eleven older patients consecutively admitted to a pyschogeriatric ward (Abarbanel Mental Health Center, Bat-Yam, Israel) due to acute mania received asenapine as monotherapy at a dosage of 10 mg twice daily for 4 weeks [Baruch et al. 2012].

Asenapine-treated subjects exhibited an 81.8% (9/11) response and a 63.6% (7/11) remission rate.

Short-term and longer-term adjunctive therapy studies of asenapine in bipolar disorder

Asenapine has also been evaluated as an adjunctive treatment in patients who were not fully responding to an ongoing mood stabilizer therapy (lithium or valproate).

Twelve-week placebo-controlled adjunctive study

The primary objective was to demonstrate the clinical superiority of asenapine compared with placebo in patients with bipolar I disorder with acute mania or mixed episode who had not fully responded to previous treatment with lithium or valproate [Szegedi et al. 2012].

Patients were eligible if they had been treated for at least 2 weeks prior to screening with a therapeutic blood level (lithium 0.6–1.2 mmol/liter or valproate 50–125 µg/ml).

A total of 326 subjects were randomized in two arms: 158 asenapine (5–10 mg twice daily)/mood stabilizer and 166 placebo/mood stabilizer.

YMRS total scores were statistically significantly improved at weeks 3 and 12 in the asenapine/mood stabilizer treatment group compared with the placebo/mood stabilizer treatment group (Table 1).

At week 12, the response and remission rates were significantly higher in the asenapine/mood stabilizer than in the placebo/mood stabilizer group (p = 0.0152 and p = 0.0148, respectively).

40-week extension adjunctive study

The aim of this 40-week extension study was to assess the safety of the combination asenapine/mood stabilizer [Szegedi et al. 2012].

Subjects completing the previous study were eligible to enter in the 40-week extension study. They were treated with a combination of asenapine/mood stabilizer (n = 38) or placebo/mood stabilizer (n = 33).

At week 52, the improvements in YMRS total scores (secondary endpoints) were not statistically significantly different between the two groups. However, these results should be interpreted with cautious because they were obtained from secondary analysis with small samples and a high dropout rate at the end of study (only 13 patients in each group completed the trial).

Post hoc analysis

Early improvement predicts later response and remission

A post hoc analysis of pooled data from two 3-week studies showed that early manic symptom improvement, in patients treated with asenapine or olanzapine, was strongly associated with response and remission at week 3 [Zhao et al. 2011]. This association was stronger for asenapine. The absence of early improvement within the first week of treatment was a predictor of subsequent nonresponse or nonremission at week 3. These results suggest that the evaluation of response in the first week may be a useful tool for individualized treatment adjustment during the early course of treatment.

Effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder with manic or mixed episodes

The effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes have been assessed in two post hoc analyses of the two 3-week studies and the 9-week extension study [Azorin et al. 2012; Szegedi et al. 2011].

The first post hoc analysis [Szegedi et al. 2011] defined three subsamples using baseline depressive symptoms: patients with a MADRS total score of at least 20, subjects with a Clinical Global Impression for Bipolar Disorder Depression (CGI-BP-D) scale severity score of at least 4, and subjects with a diagnosis of mixed episodes. At days 7 and 21 in the three groups, decreases in MADRS total score were statistically more important with asenapine than with placebo. No significant difference was found between olanzapine and placebo.

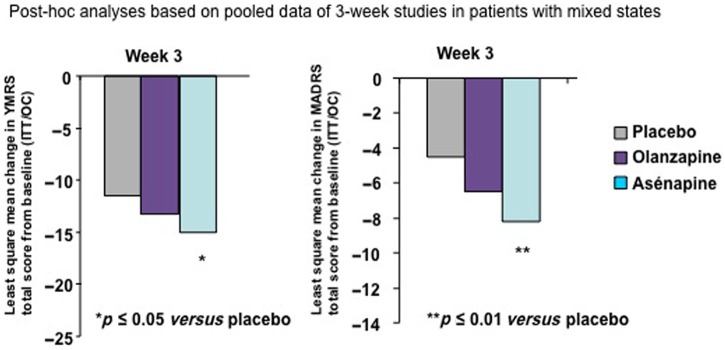

A second post hoc analysis [Azorin et al. 2012] evaluated only the effect of asenapine in patients with mixed episodes. Asenapine had a significantly greater effect on both manic and depressive symptoms compared with placebo at week 3 (differences between olanzapine and placebo were not statistically significant) (Figure 3). Asenapine showed greater efficacy than olanzapine in some specific symptoms (inner tension, inability to feel, aggressive behavior, appearance) after 3 and 12 weeks of treatment.

Figure 3.

Effects of asenapine on depressive and manic symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder with mixed states. Reproduced with permission from [Azorin et al. 2012]. ITT, intention to treat; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; OC, observed case; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Post hoc analyses show that asenapine reduced depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes. In those studies, the efficacy of olanzapine appeared to be less consistent. Prospective randomized controlled trials in bipolar depression are needed to confirm the effect of asenapine on depressive symptoms.

Summary

Asenapine has demonstrated significant efficacy compared with placebo in acute mania or mixed episodes as a monotherapy or an adjunctive therapy to mood stabilizers (lithium or valproate). Early improvement was noted on day 2 and was strongly associated with response and remission at week 3. Asenapine also appeared to be effective in treating acute mania in older patients with bipolar disorder. Post hoc analyses of asenapine showed an efficacy on depressive symptoms during manic or mixed episodes compared with placebo. The efficacy of asenapine in patients with acute mania appeared to remain constant during maintenance treatment.

Safety

The database for this safety section included the combined population of phase II/III trials in short- and long-term treatment of asenapine in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The comparators were placebo, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

Overall 4565 subjects had received sublingual asenapine, including 3457 subjects treated in the phase II and III trials [EMEA, 2010; HAS, 2011]. Within the proposed dose range, 1314 subjects received asenapine for at least 6 months and 785 for at least 12 months.

The most commonly reported adverse events, with an incidence of at least 2.0% and with a higher incidence that was twofold or more with asenapine than with placebo, were sedation (9.1% versus 4.4%), somnolence (8.4% versus 2.3%), akathisia (5.4% versus 2.4%), oral hypoesthesia (5.0% versus 0.7%) and increased bodyweight (3.5% versus 0.4%) [EMEA, 2010]. Serious adverse events were reported in 16% of asenapine-treated subjects compared with 10% in the placebo group, 12% in the olanzapine group, 18% in the risperidone group and 11% in the haloperidol group [EMEA, 2010]. The most common serious adverse events in the combined population of phase II/III trials of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were psychiatric exacerbations (schizophrenia and psychotic disorder, suicidal behaviors, manic episodes or depressed mood disorders). In the pooled analysis of the short-term trials, the proportion of subjects with a serious adverse event was 5% in the asenapine group, 7% in the placebo group and 7% in the olanzapine group.

Extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia and dyskinesias

Neurological effects in clinical trials were assessed using the Simpson Angus Rating Scale (SARS) for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BARS) for akathisia and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) for dyskinesia. The occurrence, severity and relation-to-treatment of all EPS reported as adverse events were recorded.

In the short-term and long-term mania trials, treatment-emergent EPS were observed in 10% and 15.7% of asenapine-treated patients compared with 5% and 12.7% of placebo-treated patients and 9.4% and 16.2% of olanzapine-treated patients, respectively [EMEA, 2010].

According to pooled results from both the monotherapy short-term trials, the BARS and AIMS rating scale showed comparable scores between asenapine and placebo [EMEA, 2010; McIntyre et al. 2009a, 2010b]. In the long-term 40-week extension study, the percentage of subjects worsening their AIMS scores was higher in the asenapine group versus the olanzapine group (placebo/asenapine group 3.1%, asenapine group 3.8% and olanzapine group 0%) [McIntyre et al. 2010a].

In the combined phase II/III safety data, 14 cases of tardive dyskinesia were reported in asenapine-treated patients, resulting in an incidence of 0.4% [EMEA, 2010].

Only akathisia and parkinsonism appeared to be dose related: the greatest incidence occurred with the highest dose of asenapine (10 mg twice daily). There was no dose relationship for dyskinesia and dystonia.

Metabolic and endocrine side effects

Safety data based on pooled analyses from overall phase II/III studies showed a mean body weight change of +0.8 kg in the asenapine group compared with a minimal change for placebo and +3.5 kg in the olanzapine group [EMEA, 2010]. The incidence of a clinically significant weight gain (≥7%) was 12.6% for asenapine (n = 374) compared with 31.7% for olanzapine (n = 344). In the monotherapy long-term study, the proportion of patients with weight gain of at least 7% occurred in 39.2% for asenapine and 55.1% for olanzapine [McIntyre et al. 2010a]. The change in weight for asenapine does not appear to be dose related.

The effect of asenapine related to glucose and lipid metabolism disorders was minimal.

A meta-analysis assessed the effect of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone on bodyweight and cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose metabolic parameters [De Hert et al. 2012]. These newer SGAs had demonstrated better tolerability than other SGAs (such as olanzapine or clozapine) but have not been compared. A total of 56 trials (n = 21,691) in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were included. The results highlight the lowest weight gain potential with lurasidone and the best tolerance for short-term metabolic effects with asenapine and iloperidone.

Asenapine increased prolactin levels more often than placebo but less than other comparators [EMEA, 2010]. The incidence of prolactin elevations at least two times the upper limit of normal were 6% for placebo, 28.9% for asenapine, 71.6% for risperidone, 39% for olanzapine and 38.7% for haloperidol.

Cardiovascular side effects

According to the combined phase II/III safety data, incidences of electrocardiogram QT prolongation, syncope and orthostatic hypotension were comparable in both the asenapine and olanzapine groups [EMEA, 2010].

Summary

In the different phase II and III trials, asenapine was reasonably well tolerated, especially with regard to metabolic effects.

There were minimal signs of glucose elevation or lipid changes with asenapine. The risk of weight gain appeared limited. The prolactin elevation was smaller than other antipsychotic comparators. Only oral hypoesthesia occurred as a new adverse event compared with other SGAs.

Place of asenapine in clinical practice in the management of bipolar disorder

According to the results of clinical trials, EMEA has considered that, for asenapine, the benefit/risk balance was positive for manic episodes and negative for schizophrenia [EMEA, 2010]. These results confirm the current interest of SGAs in the management of bipolar disorder in clinical practice.

The efficacy for asenapine has been demonstrated when used as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for the acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder.

It was of interest to determine the rank of use of asenapine with respect to the other SGAs in clinical practice. Overall guidelines for the management of bipolar disorder recommend lithium, valproate or a SGA as first-line treatment in acute manic episodes [Goodwin, 2009; Grunze et al. 2009; Llorca et al. 2010; Malhi et al. 2009; Yatham et al. 2009]. A meta-analysis assessed the efficacy of 17 available antimanic drugs from 38 randomized, placebo-controlled studies for acute mania or mixed episodes involving 10,800 patients [Yildiz et al. 2011]. Of the agents tested, 13 (with 7 SGAs) were more effective than placebo: aripiprazole, asenapine, carbamazepine, cariprazine, haloperidol, lithium, olanzapine, paliperdone, quetiapine, risperidone, tamoxifen, valproate and ziprasidone. Their pooled effect size for mania improvement (Hedges’ g in 48 trials) was 0.42 [confidence interval (CI) 0.36–0.48], corresponding to a moderate effect size. SGAs demonstrated greater effect sizes than mood stabilizers (lithium, anticonvulsants). The asenapine effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.40; CI 0.13–0.66) was similar to the SGA effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.40; CI 0.32–0.47). In several direct comparisons, responses to various antipsychotics were somewhat greater or more rapid than lithium, valproate or carbamazepine. Due to an onset of action slower than other antimanic agents with lithium and a teratogenic risk for women of childbearing potential with valproate, SGAs present a relevant alternative therapeutic strategy of acute mania.

The efficacy of asenapine in patients with acute mania appeared to remain constant during long-term studies. However, the primary objective of these 40-week extension studies was to assess the safety of asenapine. Well designed long-term controlled studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of asenapine as maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder.

Because of the heterogeneity of SGA class, the choice of an antipsychotic in practice is made according to its tolerability profile. While the side effects of first-generation antipsychotics are dominated by extrapyramidal symptoms, SGAs are often associated with a risk of metabolic effects (weight gain, diabetes, dyslipidemia). Asenapine, like the ‘newer’ SGAs (aripiprazole, lurasidone, iloperidone), has a favorable metabolic profile. It does not appear to have significant impact on metabolic parameters and weight gain unlike other SGAs such as olanzapine or clozapine, and to a lesser extent, risperidone and quetiapine.

Nevertheless, asenapine has a few side effects that can have a negative impact for the patient (i.e. sedation). This has to be taken into account in the benefit–risk balance.

Asenapine presents several advantages over other SGAs, such as sublingual formulation, early efficacy and good metabolic tolerability. This tolerability profile confirms the heterogeneity of the SGA class and supports the view of some authors for the need to re-evaluate the boundaries of this group.

Asenapine may be of interest in other conditions, such as depressive symptoms (due to a unique receptor binding profile) and in older patients, but well designed controlled studies are needed.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: Dr Samalin has received honoraria from Astrazeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly. Dr Charpeaud has received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Professor Llorca has received honoraria or research support from Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly.

Contributor Information

Ludovic Samalin, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand, Psychiatry B, 58, rue Montalembert, Clermont-Ferrand 63000, France.

Thomas Charpeaud, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand, Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Pierre-Michel Llorca, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand, Clermont-Ferrand, France.

References

- Azorin J., Sapin C., Weiller E. (2012) Effect of asenapine on manic and depressive symptoms in bipolar I patients with mixed episodes: results from post hoc analyses. J Affect Disord 4 August (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch Y., Tadger S., Plopski I., Barak Y. (2012) Asenapine for elderly bipolar manic patients. J Affect Disord 6 August (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishara D., Taylor D. (2009) Asenapine monotherapy in the acute treatment of both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 5: 483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwieduk C., Scott L. (2011) Asenapine: a review of its use in the management of mania in adults with bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs 25: 251–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L. (2009) Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved sublingually absorbed second-generation antipsychotic. Int J Clin Pract 63: 1762–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Yu W., Detraux J., Sweers K., van Winkel R., Correll C. (2012) Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 26: 733–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth J., Groman S., Jentsch J., Valles R., Shahid M., Wong E., et al. (2012) Asenapine effects on cognitive and monoamine dysfunction elicited by subchronic phencyclidine administration. Neuropharmacology 62: 1442–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMEA (2010) Assessment Report Sycrest. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/001177/WC500096898.pdf (accessed 7 November 2012).

- Gonzalez J., Thompson P., Moore T. (2011) Review of the safety, efficacy, and side effect profile of asenapine in the treatment of bipolar 1 disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence 5: 333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin G. (2009) Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition–recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 23: 346–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze H., Vieta E., Goodwin G., Bowden C., Licht R., Moller H., et al. (2009) The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry 10: 85–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAS (2011) Avis de la commission de transparence 2 novembre 2011. http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2011-12/sycrest_2-11-2011_avis_ct-11050.pdf (accessed 7 November 2012).

- Hedlund P. (2009) The 5-HT7 receptor and disorders of the nervous system: an overview. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206: 345–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J., Fuller M. (2011) Asenapine: a new antipsychotic option. J Pharm Pract 24: 447–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Kissling W., Davis J. (2009) Second-generation antipsychotics for schizophrenia: can we resolve the conflict? Psychol Med 39: 1591–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca P., Courtet P., Martin P., Abbar M., Gay C., Meynard J., et al. (2010) [Screening and management of bipolar disorders: results]. Encephale 36(Suppl. 4): S86–S102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi G., Adams D., Lampe L., Paton M., O'Connor N., Newton L., et al. (2009) Clinical practice recommendations for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl (439): 27–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R. (2011) Asenapine: a review of acute and extension phase data in bipolar disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther 17: 645–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R., Cohen M., Zhao J., Alphs L., Macek T., Panagides J. (2009a) A 3-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of asenapine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar mania and mixed states. Bipolar Disord 11: 673–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R., Cohen M., Zhao J., Alphs L., Macek T., Panagides J. (2009b) Asenapine versus olanzapine in acute mania: a double-blind extension study. Bipolar Disord 11: 815–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R., Cohen M., Zhao J., Alphs L., Macek T., Panagides J. (2010a) Asenapine for long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a double-blind 40-week extension study. J Affect Disord 126: 358–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R., Cohen M., Zhao J., Alphs L., Macek T., Panagides J. (2010b) Asenapine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord 122: 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R.S., Wong R. (2012) Asenapine: a synthesis of efficacy data in bipolar mania and schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 5(4): 217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S., de Queiroz V., Pagnin D., Pezawas L., Angst J., Cassano G.B., et al. (2005) Prevalence and burden of bipolar disorders in European countries. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M., Venturini P., Innamorati M., Serafini G., Telesforo L., Lester D., et al. (2011) The role of asenapine in the treatment of manic or mixed states associated with bipolar I disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 7: 259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samalin L., Tixeront C., Llorca P. (2012) Asenapine in bipolar disorder: efficacy, safety and place in clinical practice. Encephale 38: 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid M., Walker G., Zorn S., Wong E. (2009) Asenapine: a novel psychopharmacologic agent with a unique human receptor signature. J Psychopharmacol 23: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner S., Pace H. (2012) Asenapine: a clinical review of a second-generation antipsychotic. Clin Ther 34: 1023–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegedi A., Calabrese J., Stet L., Mackle M., Zhao J., Panagides J.; Apollo Study Group (2012) Asenapine as adjunctive treatment for acute mania associated with bipolar disorder: results of a 12-week core study and 40-week extension. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32: 46–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegedi A., Zhao J., van Willigenburg A., Nations K., Mackle M., Panagides J. (2011) Effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes: a post hoc analysis of two 3-week clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry 11: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham L., Kennedy S., Schaffer A., Parikh S., Beaulieu S., O'Donovan C., et al. (2009) Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2009. Bipolar Disord 11: 225–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz A., Vieta E., Leucht S., Baldessarini R. (2011) Efficacy of antimanic treatments: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 375–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Ha X., Szegedi A. (2011) Early improvement predicts later outcome in manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: post hoc analyses of asenapine studies. 9th International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, 9–11 June 2011, Pittsburgh, NJ, USA [Google Scholar]