Summary

Background

Tuberculosis is a world-wide public health problem which may clinically present in many different ways. Here we report on a patient with presumed serpiginous choroiditis (PSC) found to have latent ocular tuberculosis.

Case Report

The clinical history and physical examination, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, chest radiograph, fundus fluorescein angiography, tuberculin skin test, serological tests, and systemic evaluation carried out by consultant internist of a 42-year-old man with PSC were evaluated. The patient presented with gradual painless loss of central vision in his left eye and dark rings in the central visual field of the right eye. Upon examination, he was found to have 1 round choroidal lesion centered in the left macula and multiple serpiginous-like choroidal lesions in the right eye. Based on positive tuberculin skin test result, the patient was initially treated with anti-tubercular therapy combined with systemic corticosteroids. An immunosuppressive agent (Azathioprine) was consequently administered due to unsatisfactory response to initial therapy and the vicinity of the pathological process to the right fovea.

Conclusions

It is important to remember that tubercular choroiditis may present with clinical features of serpiginous choroiditis, requiring timely and appropriate therapy and close observation in order to prevent the progression of visual loss and recurrences.

Keywords: latent tuberculosis, case reports, choroiditis, drug therapy, posterior uveitis

Background

Intraocular tuberculosis may have a wide spectrum of clinical signs, including mutton fat keratic precipitates, fine keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, iris nodules, vitreal snowballs, snow banking, retinal vasculitis, choroiditis, serpiginous-like choroiditis, and panuveitis [1]. The diagnosis is rather challenging since all those clinical signs may also result from nontubercular causes. The definite diagnosis of intraocular tuberculosis may be based only on demonstration of presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on direct smears, in ocular fluids, or tissue cultures [2]. As this is very difficult to do in everyday praxis, most of diagnoses of intraocular tuberculosis remain presumptive, based on other evidence of tubercular infection such as positive tuberculin skin test, healed lesions on chest x-rays, or associated systemic tuberculosis [3]. Gupta et al. reported that among all these clinical signs the incidence of serpiginous-like choroiditis, vasculitis, and posterior synechiae was significantly higher in the group of uveitic patients with positive tuberculin skin test when compared to uveitic patients with negative tuberculin skin test.

Tuberculosis infection, like serpiginous choroiditis, affects the choroid and may produce similar choroidal changes [4]. These may present with geographic pattern typical of serpiginous choroiditis, with multifocal lesions like ampiginous choroiditis, and as a mixture of both [5].

Here we present a patient with presumed intraocular tuberculosis who presented with serpiginous-like choroiditis.

Case Report

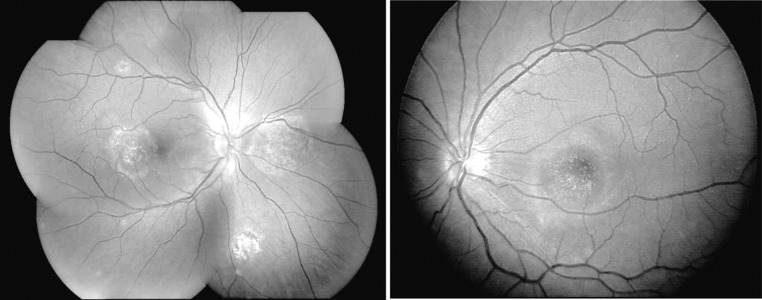

A 42-year-old man complained of deterioration in left eye (LE) visual acuity (VA) and dark rings in the central visual field of the right eye (RE) for 2 days. The patient smoked 40 cigarettes daily. LE and RE VA was 1.0 and <0.1, respectively (Snellen charts). The anterior chambers and vitreous bodies were quiet. A fundus examination revealed bilateral, multiple, round, subretinal, grayish-yellow lesions, and a peripapillary geographic yellowish lesion in the RE. All lesions had sustained activity by fluorescein angiography (FA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A, B) Red free fundus photographs of round subretinal, grayish-yellow lesions in temporal macula and nasal parapapillary region of the right eye (ampiginous form of serpiginous coroiditis) and foveal solitary lesion of the left eye (macular form of serpiginous coroiditis). There is also a peripapillary geographic subretinal yellowish lesion present in the right eye. (C, D) Fluorescein angiography, showing early hypofluorescence, (E, F) followed by late leakage in the active areas of both eyes.

Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and chest radiograph were normal. Tuberculin skin test was positive (induration diameter >10mm). All other known infective causes of posterior uveitis were ruled out by negative serological test results. Systemic evaluation was carried out by consultant internist who ruled out any concurrent systemic tubercular disease. Presumed tubercular choroiditis was diagnosed, based on the positive tuberculin skin test, clinical presentation, FA, and negative systemic workup. Given that at the moment when patient presented to us, lesions had already involved the left fovea and had begun to invade the right fovea, we decided to treat the patient with high systemic doses of corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/daily for 3 days), periocular dexamethasone injections, and anti-tubercular therapy (rifampicin 600 mg/day, isoniazid 5 mg/kg/day, ethambutol 15 mg/kg/day, and pyridoxine supplementation).

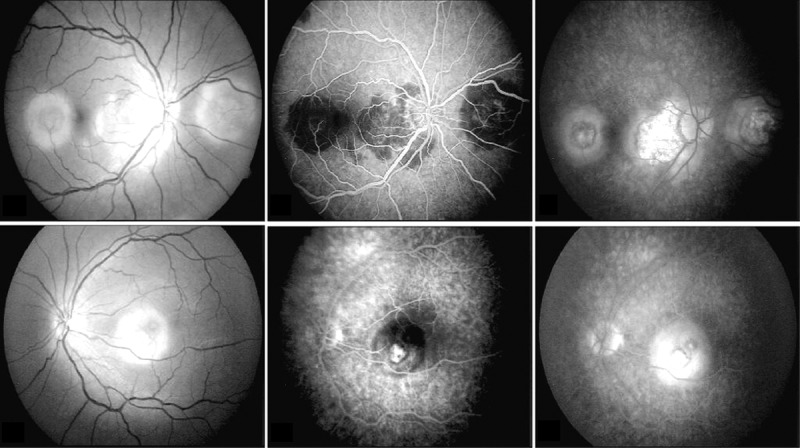

Since the disease did not show a satisfactory level of remission during the first week, we decided to add azathioprine 150 mg/daily. As the lesions started to show less activity in the next week, systemic corticosteroids were tapered over the next month. The lesions lost all activity 5 weeks after the start of treatment, and RE and LE VA were 1.0 and 0.1, respectively (Figure 2). Azathioprine and ethambutol were discontinued after 4 months and the other medications after 9 months. No recurrence occurred in the past 2.5 years of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Fundus photographs of the right and left eye, taken 5 weeks after the start of the treatment, showing healed lesions with granular appearances and minimal pigmentation.

Discussion

Choroidal involvement in intraocular tuberculosis has long been recognized as choroidal tubercles, while today we know that it can also manifest itself in the form of retinal vasculitis and serpiginous-like choroiditis [6]. To our knowledge, tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis has been described in only 1 paper, in 7 patients of Asian origin [5]. In this case report we described a case of a patient who had all the morphologic features of serpiginous choroiditis at presentation, but also had a positive tuberculin skin test, which led us to initiate anti-tubercular and corticosteroid therapy. We used high doses of corticosteroids because choroidal lesions had already heavily compromised LE visual acuity and were approaching the right fovea. For the same reason, we felt justified in also adding an immunosuppressive drug in order to gain faster control of the inflammation.

The gold standard for diagnosis of tuberculosis is microbiological demonstration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in various tissues or body liquids. Since such analysis is difficult to perform in cases of tubercular choroiditis, and because of large variations in clinical presentation, the diagnosis of intraocular tuberculosis becomes a particular challenge, especially in countries where tuberculosis is not endemic.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of serpiginous-like tubercular choroiditis is justified by the fact that the presented patient responded well to the therapy and did not have any remissions in last 2.5 years of follow-up. In addition, the patient was not assuming any therapy for last 1.5 years of follow-up, whereas patients with serpiginous choroiditis usually require low-dose maintaining corticosteroid therapy to avoid remission of the disease. Therefore, ophthalmologists must be aware of this particular manifestation of intraocular tuberculosis so that it can be diagnosed and treated as soon as possible.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interest

Authors of this manuscript did not have any proprietary interest connected to the content of this manuscript, and did not receive any grants or funds in support of this manuscript

References

- 1.Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis – an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:561–87. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas J, Madhavan HN, Gopal L, Badrinath SS. Intraocular tuberculosis. Clinicopathologic study of five cases. Retina. 1995;15:461–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, et al. Role of anti-tubercular therapy in uveitis with latent/manifest tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:772–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim WK, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Serpiginous choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:231–44. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, et al. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1744–49. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, et al. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:562–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]