Summary

Background

ALDH1 has been shown to play a role in the early differentiation of stem cells in some human malignancies. Whether cancer stem cells occur in ALDH1-associated cervical cancer is not known.

Material/Methods

We tested the hypothesis that cervical carcinomas contain subpopulations of cells that express ALDH1. The following sources of cervical carcinoma tissues were examined for the presence of stem cell marker ALDH1 by immunohistochemistry. Flow cytometric isolation of cancer cells was based on enzymatic activity of ALDH (Aldefluor assay). The mRNA and protein levels of ALDH1 were investigated by qRT-PCR and Western blot, respectively. We also detected the expression of CD133 identified as a stem cell marker for several cancers.

Results

23/89 samples of invasive squamous carcinoma and 4/20 samples of adenocarcinomas exhibited immunoreactivity to stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1). Expression of ALDH1 was found in 24.77% of the samples. Flow cytometric analysis, qRT-PCR and Western blot also confirmed the presence of small subpopulations of ALDH1-positive cells. In contrast, we found cervical carcinoma had low CD133 population.

Conclusions

Cervical carcinoma contains a small subpopulation of cells that may relate to a cancer stem cell-like phenotype, ALDH1.

Keywords: ALDH1, cervical carcinoma, cancer stem cell, CD133

Background

Cervical carcinoma is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide, with a global annual incidence of approximately 470,000 new cases and an estimated 233,000 deaths per year [1,2]. Management for early cervical cancers generally involves radical abdominal hysterectomy and radiotherapy, with good results in terms of survival and quality of life. However, the 5-year survival rate of advanced patients is from 3.2% to 13%, which is due to their resistance to the traditional treatments. This indicates that some cancer cells are not eradicated by current therapies. Mounting evidence suggests that cancer may in fact arise from a transformed stem cell that is able to self-renew, differentiate into diverse progenies, and drive continuous growth [3]. ALDH is a detoxifying enzyme that oxidizes intracellular aldehydes and confers resistance to alkylating agents [4–7]. Recent studies have shown that ALDH1 is a cancer stem cell marker and that its presence strongly correlates with tumor malignancy and self-renewal properties of stem cells in different tumors, including breast cancer, hepatoma, colon and lung cancer [8–11]]. However, whether ALDH1 can be a useful marker of CSC and/or aid cancer diagnosis in cervical carcinoma is still an open question.

Given this evidence, we investigated whether cervical carcinomas contain a tumorigenic stem cell-like population.

Material and Methods

Cell Culture

The human cervical cancer cell lines C33A, Caski, Hela and Siha were stored in our lab. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Tissue samples

Tumors from the uterine cervix were collected from archives of the Department of Gynecology at the 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Tissues were routinely fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin. A total of 112 specimens were analyzed, whose diagnoses were invasive squamous carcinoma (89 cases) and adenocarcinoma (20 cases), and normal cervical epithelium (3 cases) obtained from patients undergoing hysterectomy for various non-malignant causes served as normal controls. The median age of the patients was 47 years (range 34–56 years).

Immunohistochemical staining

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens were cut into 3μm sections and mounted on glass slides pre-treated with poly-l-Lysine. Sections were boiled for 15 minutes in citrate buffer (pH 6), cooled in the same buffer, and subsequently incubated for 10 minutes in 0.3% H2O2 to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. ALDH1 antibody (Santa Cruz) was used at a 1/100 dilution stored overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber, and rinsed in PBS. Sections were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:100) (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) for 60 minutes at room temperature, followed by ABC Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 5 minutes. All series included positive and negative controls. Replacement of the monoclonal antibody with mouse IgG1 protein of the same concentration was used as a negative control. Immunohistochemical staining of ALDH1 was classified as 3+ (≥50% positive tumor cells), 2+ (<50% but ≥10%), 1+ (<10%), or negative (0%). CD133 antibody (ab19898) and Smad3 antibody (ab28379) were used at a 1/100 dilution with anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ab6721). All slides were evaluated by 2 independent pathologists.

ALDEFLUOR assay and separation of the ALDH-positive population by FACS

The population with high ALDH enzymatic activity was isolated by use of the ALDEFLUOR kit (StemCell Technologies, Durham, NC). Cells were suspended in ALDEFLUOR assay buffer containing ALDH substrate (BAAA, 1 μmol/l per 1×106 cells) and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C to allow the conversion of Aldefluor substrate, a green fluorescent product retained within the cell due to its negative charge. For each experiment, an aliquot of Aldefluor-stained cells was immediately quenched with 5 μL 1.5 mM diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), a specific ALDH inhibitor, to serve as a negative control. The sorting gates were established using as negative controls the cells stained with PI only; for viability, the ALDEFLUOR-stained cells treated with DEAB; and the staining with secondary antibody alone.

Flow cytometry for CD133

Cells were blocked with FcR blocking reagent and stained with CD133 mouse IgG1 antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA). Mouse IgG1-PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was the isotype control antibody.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

All reactions were done in a 20 μL reaction volume in triplicate by SYBR Green Real-time PCR Universal Reagent (GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and MX-3000P Real-time PCR machine (Stratagen). Standard curves were generated and the relative amount of ALDH1 and CD133 were normalized to β-actin (2−ΔCt). ALDH1 and CD133 expression fold change were evaluated using 2−ΔΔCt. Primers are ALDH1 (forward, 5′-CTGCTGGCGACAATGGAGT-3′; reverse, 5′-GTCAGCCCAACCTGCACAG-3′), CD133 (forward, 5′-CAACCCTGAACTGAG GCAGC-3′; reverse, 5′-TTGATAGCCCTGTTGGACCAG-3′) and β-actin (forward, 5′-GCATGGGTCAGAAGGATTCCT-3′; reverse, 5′-TCGTCCCAGTTGGTGACGAT-3′) was used as endogenous control. These primers yielded 111-, 103-, and 106-bp products, respectively.

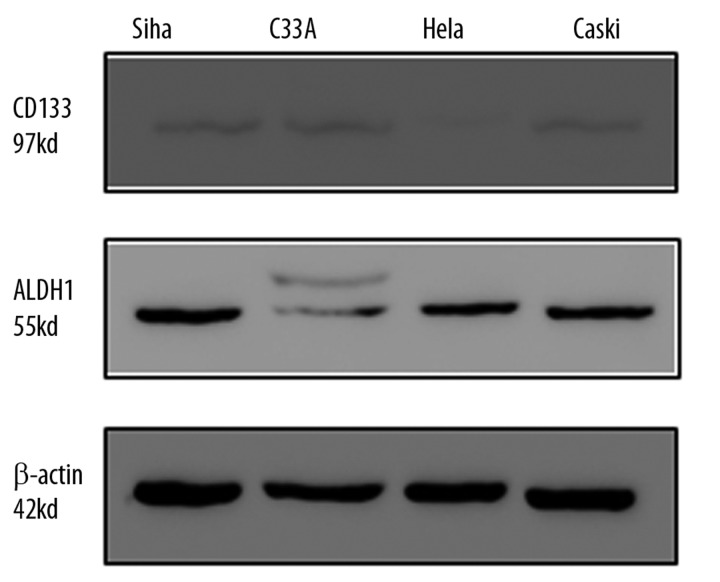

Western blot

Protein was extracted from cervical cancer cell lines C33A, Caski, Hela and Siha. Briefly, 10 μg protein of each sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels, electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated overnight at 4°C in Tris buffered saline with 0.05% tween (TBST) containing 5% dry milk and detected with mouse monoclonal IgG1 anti-ALDH1(BD, USA), rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-CD133 (Abcam, USA) and commercial ECL kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein loading was estimated using mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, USA) and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (MultiSciences Biotech Co. Ltd).

Results

ALDH1 expression and localization in cervical carcinoma tissues

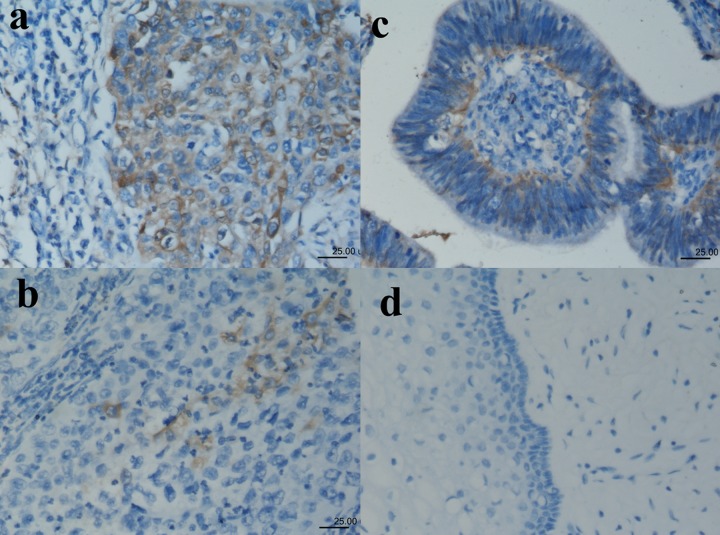

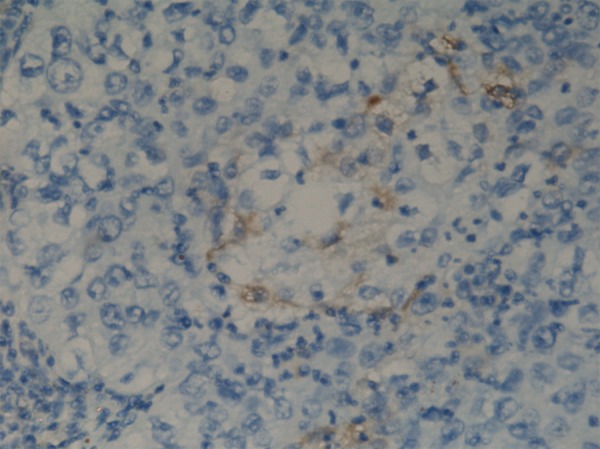

ALDH1 expression was observed in 23/89 (89 cases) cases of invasive squamous carcinoma and 4/20 cases of adenocarcinoma (20 cases) (Figure 1A–D). No ALDH1 was expressed in normal cervical epithelium obtained from patients undergoing hysterectomy for various non-malignant causes. The majority of positive staining demonstrated focal moderate staining, and occasionally moderate diffuse staining with moderate intensity. Among positive staining cases in primary cervical carcinomas and metastatic carcinomas, staining tended to be diffuse, with a spectrum ranging from weak to moderate-to-strong. The results of immunostaining of the tumor microarrays, organized according to clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients, are shown in Table 1. Correlation was found between the expression of the ALDH1 and lymph nodal metastasis in cervical carcinoma, and patients with recurrent disease were more likely to have a higher ALDH1 expression (Table 1). We also found the expression of ALDH1 has some relationship with Smad3 (Table 2). The immunohistochemical study showed there was almost no CD133-positive area (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Immunoreactivity patterns of ALDH1 in cervical squamous carcinomas (A, B), adenocarcinomas (C) and normal epithelium (D). (A) Diffuse positive staining for ALDH1 in cervical squamous carcinomas. (B) Squamous carcinoma cells (<10%) show cytoplasmic staining for ALDH1. (C) Adenocarcinoma cells (<50% but ≥10%) show cytoplasmic staining for ALDH1. (D) ALDH1-negative staining in normal epithelium.

Table 1.

Relationship between ALDH1 expression and clinicopathological parameters of cervical carcinoma.

| − | + | ++ | +++ | Positive (%) | χ2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | >0.05 | |||||||

| ≤40 | 43 | 30 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 30.23 | 1.1369 | |

| >40 | 66 | 52 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 21.21 | ||

| Tumor diameter | >0.05 | |||||||

| <4cm | 74 | 55 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 25.68 | 0.1013 | |

| ≥4cm | 35 | 27 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 22.86 | ||

| Histological type | >0.05 | |||||||

| Squamous carcinoma | 89 | 66 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 25.84 | 0.0678 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 20.00 | ||

| FIGO stage | >0.05 | |||||||

| Ib | 71 | 54 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 23.94 | 0.0747 | |

| IIa | 38 | 28 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 26.32 | ||

| Lymph nodal metastasis | <0.05 | |||||||

| − | 81 | 67 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 17.28 | 9.4844 | |

| + | 28 | 15 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 46.43 | ||

| Differentiation | >0.05 | |||||||

| Well | 27 | 23 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 14.81 | 1.2649 | |

| Mediate or Poor | 82 | 59 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 28.05 | ||

| Recurrence or metastasis | <0.05 | |||||||

| − | 100 | 81 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 19.00 | 18.0545 | |

| + | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 88.89 |

Table 2.

The relationship of ALDH1 and Smad3.

| Smad3 | Total | ALDH1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | ||

| + | 59 | 26 | 33 |

| − | 50 | 1 | 49 |

Figure 2.

Few CD133 positive cells in cervical carcinoma.

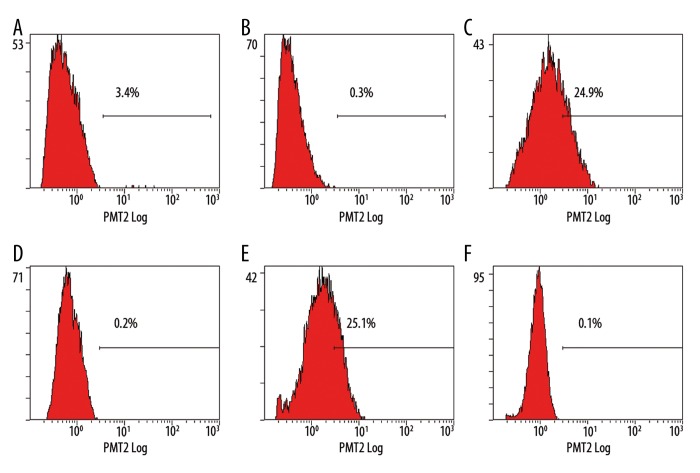

The ALDEFLUOR-positive population isolated from cervical cell properties

Single-cell suspensions of cells were obtained by enzymatic digestion. We utilized the ALDEFLUOR assay to assess the presence and size of the population with ALDH enzymatic activity in normal human breast epithelium. Analysis of C33A, Caski, Hela and Siha cells showed an average of 3.1±0.26%, 22.07±2.63%, 11.63±3.54% and 27.53±3.96% ALDEFLUOR-positive population, respectively (Figure 3A–F).

Figure 3.

The ALDEFLUOR-Positive Population Isolated from Cervical Cell Properties. (A) ALDEFLUOR-positive population of C33A (B) Control of C33A (C) ALDEFLUOR-positive population of Caski (D) Control of Caski (E) ALDEFLUOR-positive population of Siha (F) Control of Siha.

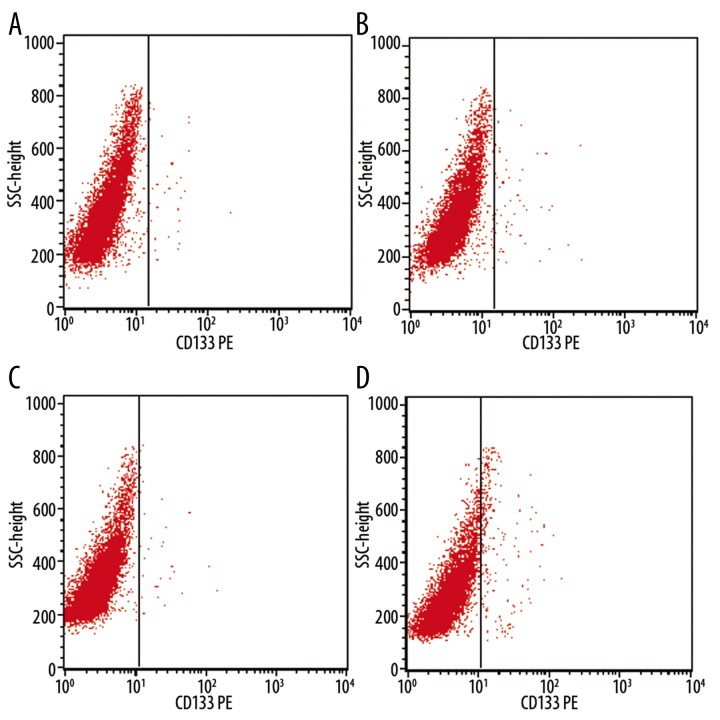

We also studied expression of CD133 by the cervical cancer cell lines C33A, Caski, Hela and Siha. Figures 4A–D show the 0.22±0.01%, 0.67±0.03%, 0.43±0.06% and 3.78±1.02% CD133-positive populations, respectively (the control antibody background was not subtracted because it did not overlap CD133 fluorescence).

Figure 4.

The expression of CD133 in cervical cancer cell lines by flow cytometry. (A) C33A (B) Caski (C) Hela (D) Siha.

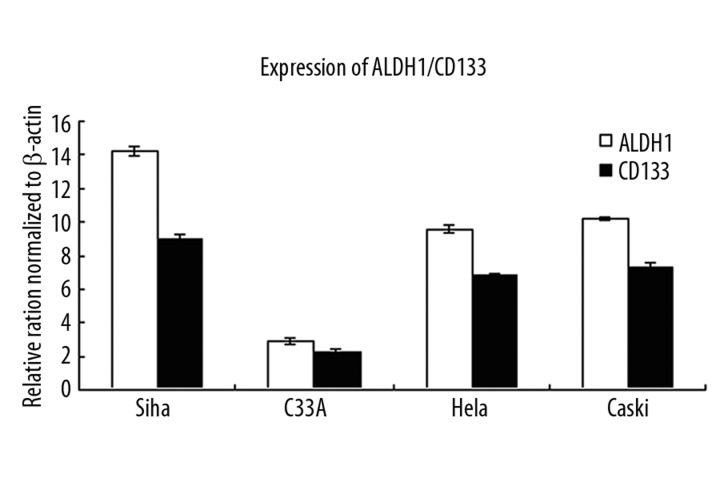

ALDH1 mRNA expression

ALDH1 mRNA expression was significantly higher in cervical cell lines than was CD133 mRNA expression (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Expression of ALDH1 and CD133 on mRNA level.

ALDH1 protein expression

ALDH1 protein was detected as a single band at 55 kDa in all of the cervical cell lines tested by Western blot (Figure 6). Densitometry analysis of the blots showed lower levels of CD133 in cervical cell lines. There was a positive correlation between ALDH1 protein expression and ALDH1 enzymatic activity.

Figure 6.

Expression of ALDH1 and CD133 on protein level.

Discussion

The cancer stem cell hypothesis supposes that the cancer stem cells may relate to the cancer risk assessment, early detection, prognostication and prevention. The development of more effective cancer therapies [12] may require targeting cancer stem cell populations. The success of these new approaches concentrates on the identification, isolation, and characterization of cancer stem cells. However, the phenotype of these cells has remained elusive [13,14]. The study of cervical cancer SC would be greatly enhanced by availability of specific markers to identify and isolate these cells. The aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) families of enzymes are cytosolic isoenzymes that are responsible for oxidizing intracellular aldehydes and contributing to the oxidation of retinol to retinoic acid in early stem cell differentiation [15]. Visus et al. suggested that ALDH1A1 is a marker for distinguishing premalignant cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [16], and the increased incidence of ALDH1 expression correlated positively with the staging of patients. Bin Chang et al. analyzed the associations between the expression of the ALDH1 and clinical factors (diagnosis, tumor grade, stage, and clinical response to chemotherapy), as well as overall and disease-free survival. They found ALDH1 was a favorable prognostic factor of ovarian carcinoma. In breast carcinomas, the expression of ALDH1 detected by immunostaining was correlated with poor prognosis [7]. A key finding of our study was that immunohistochemistry identifies a small subpopulation of ALDH1+ cells localized in the cervical carcinoma. In the current study, high levels of ALDH1 expression were observed in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease, suggesting that ALDH1 might be a potential independent prognosis predictor in cervical cancer.

Loss of responsiveness to TGF-β-induced cell growth inhibition during cancer development is a feature of many tumors, including cervical cancer. In this study, we found that increased Smad3 protein expression in cervical cancers was associated with ALDH1 expression.

A second key finding of our study is that ALDH-based markers can be used to track cervical SC during cervical tumorigenesis. Utilizing in vitro assays, the enzymatic activity of ALDH has been used to isolate SC subpopulations. ALDH activity in cells was measured by using dansyl aminoacetaldehyde, and the activity of ALDH was used to isolate precursor cells. Unlike the previously described breast cancer stem cell phenotype, which requires the use of a combination of 10 surface antigens [17], testing for ALDH1 activity is a simple method for identifying normal and cancer stem cells. Cells with high ALDH activity contain the tumorigenic cell fraction able to self-renew and to recapitulate the heterogeneity of the parental tumor. These cells may also have the highest ability to grow in vivo in a xenotransplantation animal model.

We observed high levels of ALDH1 in primary cultures obtained from resected tumor tissue, confirming that ALDH1 overexpression is not a phenomenon restricted to established cell lines.

Thus far cellular markers including CD133 have been used to identify CSCs in several tumors. Recently, the relevance of CD133 as a reliable CSC marker has been doubted, since it was shown that even CD133-negative GBM cells may behave as brain CSCs [18]. However, in cervical carcinoma, we found the expression of CD133 was very limited.

Conclusions

Since ALDH1 is also expressed in hematopoietic and neuronal stem cells, this marker may prove useful for the detection and isolation of cancer stem cells in other malignancies, thus facilitating the application of cancer stem cell biology to clinical practice. Our study suggests that ALDH1 expression may be used to detect cervical cancer stem cells. Identification of ALDH1 as a potential marker of cancer stem cells opens important new avenues of research in cervical carcinogenesis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

All database searches were carried out by staff according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Collection of patient data was kept to a minimum and data were stored in a secure manner in a database under the control of the University of Sun Yat-Sen, to which only the corresponding author has access.

Source of support: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (30672221 and 30872743), Guangdong province Natural Scientific Grant (6021279), Science Technology Planning Key Project of Guangdong Province (2009A030301006), Guangzhou Science and Technology Plan(2010J-E291) and Key Clinical Program of the Ministry of Health([2010]439)

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer–burden and assessment of causality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–11. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magni M, Shammah S, Schiro R, et al. Induction of cyclophosphamide-resistance by aldehyde-dehydrogenase gene transfer. Blood. 1996;87:1097–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sophos NA, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase gene superfamily: the 2002 update. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143–144:5–22. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:549–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dylla SJ, Beviglia L, Park IK, et al. Colorectal cancer stem cells are enriched in xenogeneic tumors following chemotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma S, Chan KW, Lee TK, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase discriminates the CD133 liver cancer stem cell populations. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1146–53. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3382–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:330–38. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottwald L, Lech W, Sobotkowski J, et al. Transvaginal doppler sonography for assessment the response to radiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cervical cancer: a preliminary study. Arch Med Sci. 2009;5(3):459–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villadsen R, Fridriksdottir AJ, Ronnov-Jessen L, et al. Evidence for a stem cell hierarchy in the adult human breast. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:87–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3382–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visus C, Ito D, Amoscato A, et al. Identification of human aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 as a novel CD8+ T-cell-defined tumor antigen in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10538–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida A. Molecular genetics of human aldehyde dehydrogenase. Pharmacogenetics. 1992;2:139–47. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beier D, Hau P, Proescholdt M, et al. CD133(+) and CD133(−) glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cells show differential growth characteristics and molecular profiles. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4010–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]