Crystals of the phosphotriesterase from M. tuberculosis were obtained and diffraction data were collected and processed to 2.27 Å resolution. An analytical ultracentrifugation experiment suggested that mPHP exists as dimers in solution.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, phosphotriesterases

Abstract

Organophosphates (OPs) are extremely toxic compounds that are used as insecticides or even as chemical warfare agents. Phosphotriesterases (PHPs) are responsible for the detoxification of OPs by catalysing their degradation. Almost 100 PHP structures have been solved to date, yet the crystal structure of the phosphotriesterase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (mPHP) remains unavailable. This study reports the first crystallization of mPHP. The crystal belonged to space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 68.03, b = 149.60, c = 74.23 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. An analytical ultracentrifugation experiment suggested that mPHP exists as a dimer in solution, even though one molecule is calculated to be present in the asymmetric unit according to the structural data.

1. Introduction

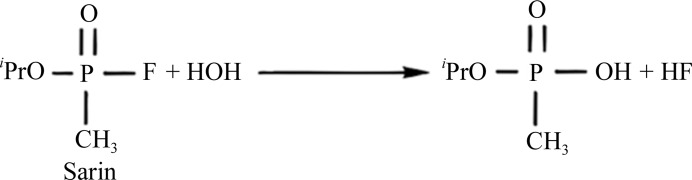

Organophosphates (OPs) are highly toxic compounds which are commonly used for eliminating insect pests and include chemical warfare agents such as sarin, soman and VX (Raushel, 2002 ▶). This class of small molecules irreversibly inhibit acetylcholinesterase and are therefore deadly toxic to the nervous system (Merone et al., 2005 ▶). Phosphotriesterases (PHPs), which belong to the amidohydrolase superfamily (LeJeune et al., 1998 ▶), are regarded as typical enzymatic antidotes for OPs. PHPs catalyse the hydrolysis of a broad range of compounds, including phosphoesters, esters and amides (Elias et al., 2008 ▶). The classical degradation of the nerve agent sarin by PHPs is shown in Fig. 1 ▶.

Figure 1.

Degradation of the nerve agent sarin by PHPs.

Most PHPs have been characterized as double zinc ion-binding proteins and have been reported to form monomers (Buchbinder et al., 1998 ▶) or dimers (McDaniel et al., 1988 ▶) in solution. In this study, we crystallized the phosphotriesterase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (mPHP) and collected a data set at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) in the People’s Republic of China. Furthermore, an analytical ultracentrifugation experiment suggested that mPHP forms dimers in solution.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning and transformation

The gene encoding the phosphotriesterase mPHP was PCR-amplified from the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. BamHI and EcoRI restriction sequences were added to the sense (5′-CGGGATCCATGCCAGAACTAAATACCGCTCGCG-3′) and antisense (5′-GGAATTCTCACTGATAGCCGCCCTGCC-3′) primers, respectively. Purified PCR fragments were digested by the two restriction enzymes and inserted into the pET28a(+) vector (Novagen). The recombinant plasmid was sequenced and transformed into competent Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells for expression.

2.2. Expression and purification

The E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells containing the recombinant plasmid were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 µg ml−1 kanamycin and 1 mM ZnSO4. The bacterial cells were grown at 310 K with shaking at 200 rev min−1 until the OD600 reached 0.6. Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the culture to a final concentration of 500 µM for induction. His-tagged mPHP protein was expressed by extending the culture time by an additional 24 h at 289 K with shaking at 200 rev min−1.

The cells were harvested by centrifugation (Beckman/Coulter Avanti J-26XP) at 5000 rev min−1 and 277 K for 30 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in cold lysis buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10%(v/v) glycerol and lysed by sonication on ice. The supernatant was obtained by centrifuging the cell lysate at 18 000 rev min−1 and 277 K (Beckman/Coulter AvantinJ-26XP) for 1 h. A typical nickel-affinity chromatography method (GE Healthcare) was applied for preliminary purification of the mPHP protein from the supernatant. The Ni–NTA resin was pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer described above and applied to the supernatant. After extensively washing the resin with lysis buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole, the bound protein was eluted with elution buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10%(v/v) glycerol, 300 mM imidazole]. The eluted mPHP protein was dialysed against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl overnight and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 column (GE Healthcare). The purified mPHP protein was submitted to SDS–PAGE for quality evaluation and concentrated to 10 mg ml−1 for crystallization.

2.3. Crystallization and data collection

Crystallization was performed at 293 K using the vapour-diffusion method with either sitting drops (for screening) or hanging drops (for optimization): 1 µl protein solution (10 mg ml−1) was mixed with 1 µl reservoir solution and equilibrated against 100 µl reservoir solution. Commercial crystallization kits from Hampton Research and Emerald BioSystems were employed in the screening experiment. Initial micro-crystals were observed in Crystal Screen 2 condition No. 35 (Hampton Research) and Wizard 3 condition No. 28 (Emerald BioSystems) kits after 24 h. Both conditions consisted of 70% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5. Following additive screening (Hampton Research), we determined the optimal reservoir solution for crystallization to be 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0, 55% MPD, 150 mM NaSCN.

Diffraction data were collected on beamline BL17U at the SSRF synchrotron. The data set was processed using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

2.4. Analytical ultracentrifugation assay of mPHP

Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) was performed using a Beckman/Coulter XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge with six-channel centrepieces and sapphirine windows at 42 000 rev min−1 and 277 K. 100 µl purified mPHP protein (1 mg ml−1) was loaded for the assay. No substrate or ligand was added for the assay.

3. Results

Our study started with the optimization of the protein-expression conditions. The initial expression of mPHP in basic LB medium without ZnSO4 yielded very little protein. Moreover, no crystals were obtained when screening crystallization conditions using this batch of protein. Given that PHPs are mostly Zn2+-dependent (Buchbinder et al., 1998 ▶) and metal-ion deficiency can compromise the expression or even cause structural disruption of metal-binding proteins in E. coli, we decided to test whether a zinc supplement in the medium would improve the protein yield. It turned out that mPHP production was three to five times higher (up to 2 mg of mPHP purified from 1 l medium) when using medium supplemented with ZnSO4 than with the initial condition. The protein product was also adequate for the subsequent experiments.

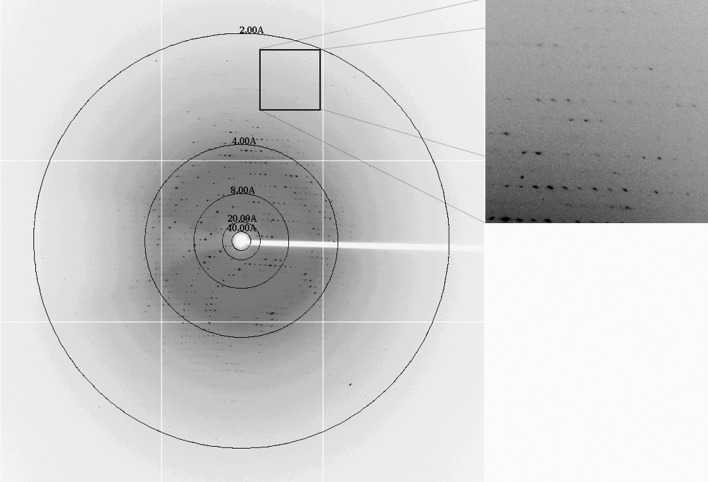

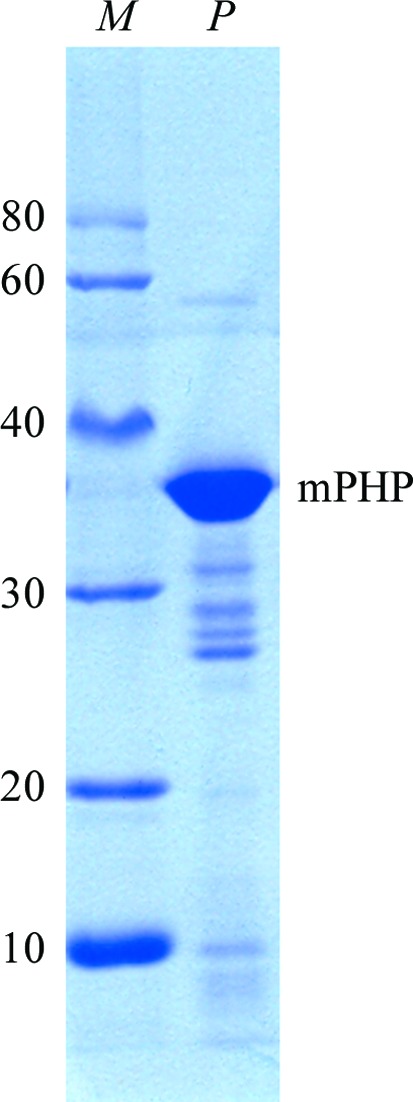

The purity of the mPHP that we prepared was evaluated by SDS–PAGE and was fairly high despite some degradation (Fig. 2 ▶). In the crystallization experiment, rod-like crystals were observed in the hanging drops (Fig. 3 ▶). The crystals appeared small, thin and fragile, and no diffraction spots could be observed when using our in-house X-ray system (R-AXIS HTC, Rigaku). However, the quality of the diffraction data collected at the SSRF synchrotron was significantly improved (Fig. 4 ▶). For the best data set collected, the maximal resolution was 2.27 Å in space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 68.03, b = 149.60, c = 74.23 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. Detailed statistics of this data set are summarized in Table 1 ▶. We are currently in the process of solving the structure of mPHP using the molecular-replacement method with the structure of E. coli phosphotriesterase (PDB entry 1bf6; Buchbinder et al., 1998 ▶) as the search model.

Figure 2.

Coomassie Blue-stained 12% SDS–PAGE showing recombinant mPHP before crystallization. Lane M, Protein Ruler I (TransGen Biotech; labelled in kDa). Lane P, recombinant mPHP protein.

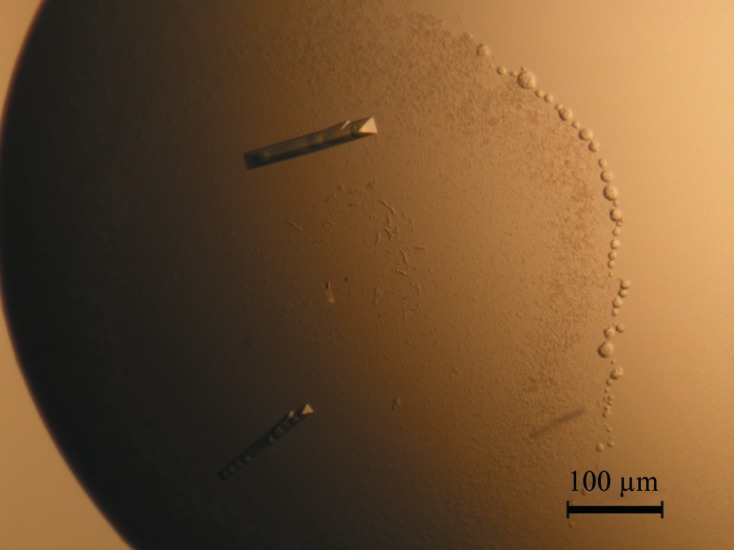

Figure 3.

Rod-like crystals of mPHP used for data collection at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility with a wavelength of 1.005 Å.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction pattern of the mPHP crystal. The circles from the edge to the centre indicate 2, 4, 8, 20 and 40 Å resolution, respectively.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outermost resolution shell.

| Space group | C2221 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 68.03, b = 149.60, c = 74.23, α = β = γ = 90 |

| Matthews coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 2.73 |

| Solvent content (%) | 55 |

| No. of molecules in the asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.005 |

| Light source | SSRF BL17U, U25 |

| Detector | MX225 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.27 |

| No. of observed reflections | 128164 |

| No. of unique reflections | 17797 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (99.0) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 13.9 (1.82) |

| Multiplicity | 7.2 (7.4) |

| R merge † | 0.119 (0.446) |

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of the reflection.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of the reflection.

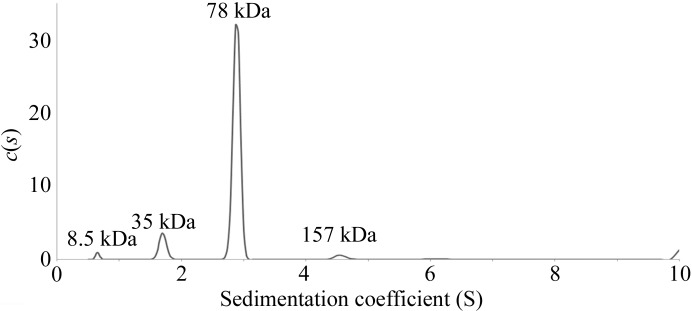

The calculated Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶; Kantardjieff & Rupp, 2003 ▶) strongly indicated that one mPHP molecule was present in the asymmetric unit with a solvent content of 55%. The calculated solvent content correlated well with the resolution of our data set. This finding is inconsistent with the previous reports that most PHPs form dimers (Bernstein et al., 1977 ▶; McDaniel et al., 1988 ▶; Vanhooke et al., 1996 ▶; Benning et al., 2000 ▶; Berman et al., 2000 ▶, 2003 ▶; Elias et al., 2008 ▶), although a few monomeric PHPs have also been reported (Buchbinder et al., 1998 ▶). In order to determine the polymerization status of mPHP, we performed an AUC experiment and found that the protein existed as dimers in solution (Fig. 5 ▶).

Figure 5.

Analytical ultracentrifugation assay for mPHP. The AUC results are presented as a c(M) distribution model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility beamline BL17U for data collection and Dr Wenqing Shui for improving the language. This study was supported by the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 31000345 and 31000056), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program; grant No. 2010CB833600) and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China (grant No. 09JCZDJC18000).

References

- Benning, M. M., Hong, S.-B., Raushel, F. M. & Holden, H. M. (2000). J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30556–30560. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H., Henrick, K. & Nakamura, H. (2003). Nature Struct. Biol. 10, 980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, F. C., Koetzle, T. F., Williams, G. J., Meyer, E. F., Brice, M. D., Rodgers, J. R., Kennard, O., Shimanouchi, T. & Tasumi, M. (1977). Eur. J. Biochem. 80, 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, J. L., Stephenson, R. C., Dresser, M. J., Pitera, J. W., Scanlan, T. S. & Fletterick, R. J. (1998). Biochemistry, 37, 5096–5106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elias, M., Dupuy, J., Merone, L., Mandrich, L., Porzio, E., Moniot, S., Rochu, D., Lecomte, C., Rossi, M., Masson, P., Manco, G. & Chabriere, E. (2008). J. Mol. Biol. 379, 1017–1028. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kantardjieff, K. A. & Rupp, B. (2003). Protein Sci. 12, 1865–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- LeJeune, K. E., Wild, J. R. & Russell, A. J. (1998). Nature (London), 395, 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, C. S., Harper, L. L. & Wild, J. R. (1988). J. Bacteriol. 170, 2306–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Merone, L., Mandrich, L., Rossi, M. & Manco, G. (2005). Extremophiles, 9, 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raushel, F. M. (2002). Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5, 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vanhooke, J. L., Benning, M. M., Raushel, F. M. & Holden, H. M. (1996). Biochemistry, 35, 6020–6025. [DOI] [PubMed]