Natural killer cells can act as rheostats, or ‘master regulators’, controlling antiviral T-cell responses.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature10624) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Subject terms: NK cells, CD8-positive T cells, Gene regulation in immune cells, Viral pathogenesis

Immunoregulation by natural killer cells

In mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, a model for human hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, natural killer (NK) T cells are shown to regulate antiviral T-cell immunity by directly killing activated CD4 T cells. This immunoregulatory role is in addition to the direct antiviral effects of NK cells.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature10624) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Abstract

Antiviral T cells are thought to regulate whether hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections result in viral control, asymptomatic persistence or severe disease, although the reasons for these different outcomes remain unclear. Recent genetic evidence, however, has indicated a correlation between certain natural killer (NK)-cell receptors and progression of both HIV and HCV infection1,2,3, implying that NK cells have a role in these T-cell-associated diseases. Although direct NK-cell-mediated lysis of virus-infected cells may contribute to antiviral defence during some virus infections—especially murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infections in mice and perhaps HIV in humans4,5—NK cells have also been suspected of having immunoregulatory functions. For instance, NK cells may indirectly regulate T-cell responses by lysing MCMV-infected antigen-presenting cells6,7. In contrast to MCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection in mice seems to be resistant to any direct antiviral effects of NK cells5,8. Here we examine the roles of NK cells in regulating T-cell-dependent viral persistence and immunopathology in mice infected with LCMV, an established model for HIV and HCV infections in humans. We describe a three-way interaction, whereby activated NK cells cytolytically eliminate activated CD4 T cells that affect CD8 T-cell function and exhaustion. At high virus doses, NK cells prevented fatal pathology while enabling T-cell exhaustion and viral persistence, but at medium doses NK cells paradoxically facilitated lethal T-cell-mediated pathology. Thus, NK cells can act as rheostats, regulating CD4 T-cell-mediated support for the antiviral CD8 T cells that control viral pathogenesis and persistence.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature10624) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Main

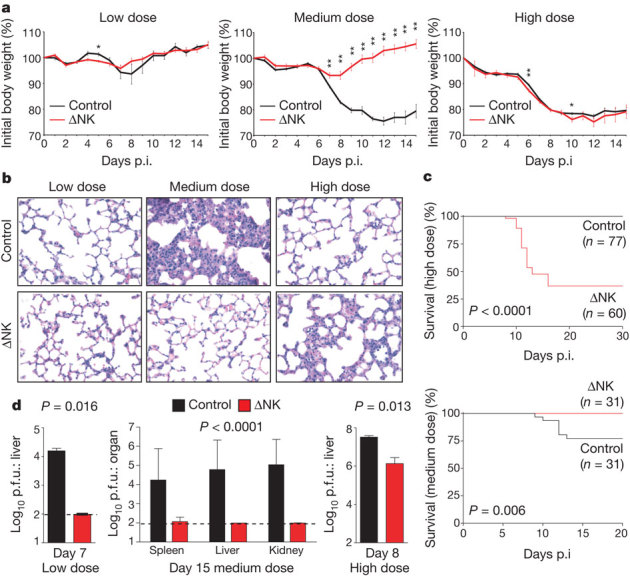

Intravenous (i.v.) inoculation of C57BL/6 mice with a low (5 × 104 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.), medium (2 × 105 p.f.u.), or high (2 × 106 p.f.u.) dose of LCMV, strain clone 13, resulted in different degrees of pathology, as indicated by weight loss (Fig. 1a) and by histological analysis of lung sections at day 15 post-infection (p.i.) (Fig. 1b). The high dose caused a precipitous drop in body weight during the first week of infection (Fig. 1a, right) but, thereafter, clonal exhaustion and deletion of LCMV-specific T cells resulted in a persistent infection9,10 associated with minimal lung pathology (Fig. 1b, right) and 100% (77 of 77) survival (Fig. 1c, top). Selective depletion of NK cells using 25 μg of anti-NK1.1 monoclonal antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 1) 1 day before high-dose infection resulted in 58% (35 of 65) mortality between days 9 and 13 of infection (Fig. 1c, top) associated with severe pulmonary oedema (data not shown) and reduced viral titres by day 7 p.i. (Fig. 1d, right). Under these high-dose conditions, therefore, the presence of NK cells promoted persistence and prevented mortality.

Figure 1. NK cells influence T-cell-dependent pathology and viral persistence during LCMV infection.

a–d, C57BL/6 mice treated with IgG2a (Control) or anti-NK1.1 (ΔNK) were infected with low (5 × 104 p.f.u.), medium (2 × 105 p.f.u.), or high (2 × 106 p.f.u.) doses of LCMV. a, Weight loss (mean ± s.e.m.) during infection (n = 3–43 per group per day), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. b, Haematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining of lung (×400) at day 15 p.i. c, Survival after high- or medium-dose infection. d, Viral titres (mean ± s.e.m.) after low (day 7, n = 3 per group), medium (day 15, n = 9–15 per group), or high (day 8, n = 3 per group) dose infection. Dotted line represents limit of detection.

In contrast to the beneficial role of NK cells during high-dose infection, NK-cell depletion prevented the severe weight loss (Fig. 1a, middle) and tissue pathology (Fig. 1b, middle) associated with the medium dose of LCMV. Twenty-three per cent (7 of 31) of control-treated mice succumbed to the medium dose during the second week of infection, and the lungs of surviving mice exhibited bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue, pulmonary oedema and interstitial mononuclear infiltration. Lung pathology was absent in NK-cell-depleted mice, which uniformly survived medium-dose challenge (Fig. 1c, bottom). Moreover, although high levels of replicating virus persisted in surviving control mice at day 15 p.i., NK-cell depletion resulted in complete viral clearance (Fig. 1d, middle). In this case the presence of NK cells was detrimental for the host, as they promoted immune pathology and death.

Irrespective of the presence of NK cells, inoculation with a low dose of virus was uniformly non-lethal in 18 of 18 (100%) control and 18 of 18 (100%) of NK-cell-depleted mice by >50 days p.i., with minimal weight loss (Fig. 1a, left) and minimal lung pathology (Fig. 1b, left). Virus was completely cleared in both groups of mice by day 15 of low-dose infection (data not shown), but NK-cell depletion resulted in more rapid elimination of LCMV in liver by day 7 p.i. (Fig. 1d, left).

The weight loss, lung pathology and mortality observed in medium-dose-infected wild-type mice (Fig. 1a, b) did not occur after infection of αβ T-cell-receptor-deficient (Tcrb−/− )mice, and NK-cell depletion of Tcrb−/− mice did not alter weight loss or viral burden (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, NK cells regulate viral clearance and immunopathology during LCMV infection through a T-cell-dependent mechanism.

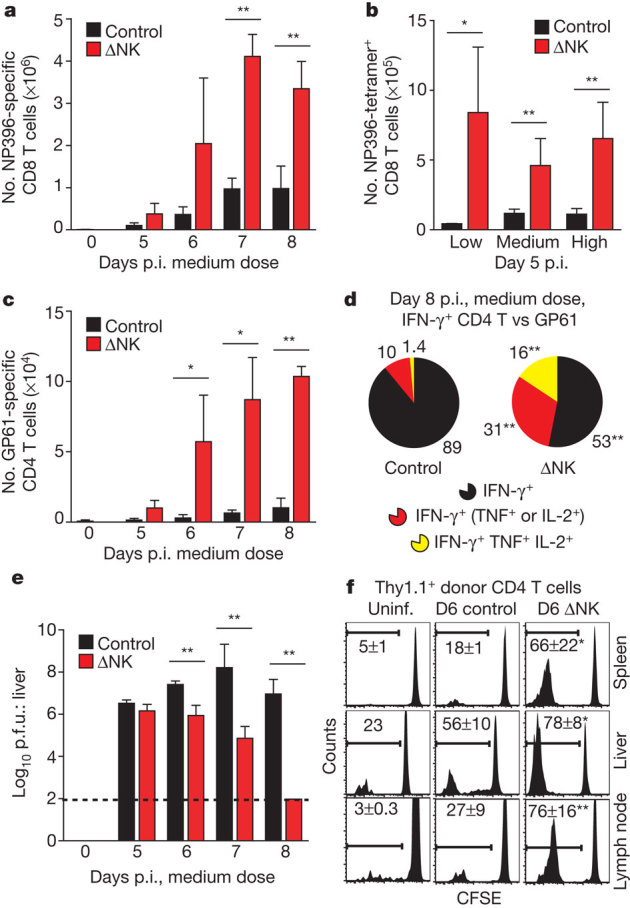

As early as day 6 after medium-dose infection, the proportion and number of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)+ LCMV-specific CD8 T cells was increased two- to sixfold in mice depleted of NK cells (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3), and antiviral T cells from these mice showed an enhanced ability to co-produce tumour necrosis factor (TNF) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The number of LCMV epitope NP396–404 tetramer-binding CD8 T cells in the spleen on day 5 p.i. was increased 4- to 20-fold in NK-cell-depleted mice relative to non-depleted control mice after infection with all doses of virus (Fig. 2b). The number of virus-specific IFN-γ+ CD4 T cells was also amplified 7- to 20-fold by NK-cell depletion compared to control mice on different days after medium-dose infection (Fig. 2c). Moreover, co-production of TNF and interleukin-2 (IL-2) by antiviral CD4 T cells was augmented by NK-cell depletion (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3). The increased magnitude of the LCMV-specific T-cell response in the absence of NK cells during medium-dose infection correlated with rapid viral clearance (Fig. 2e). Depletion of NK cells using a carefully titrated dose of anti-asialo GM1 antibody, which eliminates NK cells but not CD8 T cells11, also enhanced antiviral CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses during medium-dose infection (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2. LCMV-specific T-cell responses enhanced in NK-cell-depleted mice.

a–c, Number (mean ± s.e.m.) of LCMV-specific T cells measured by IFN-γ expression (a, c) or tetramer-binding (b) at various days p.i. (a, c) (medium dose, n = 3 per group per day) or at day 5 p.i. (b) (various doses, n = 3–11 per group). d, Co-production of TNF and IL-2 by gated IFN-γ+ CD4 T cells (day 8 p.i., medium dose) after in vitro stimulation with GP61 peptide. e, Viral titres in liver (n = 3–11 per group per day, medium dose). f, CFSE dilution by donor (Thy1.1+) CD4 T cells in uninfected (Uninf.) and infected (medium dose, day 6 p.i.) control and ΔNK Thy1.2+ host mice. Control versus ΔNK mice, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The enhanced antiviral T-cell responses suggested that NK-cell depletion may augment proliferation of LCMV-specific T cells. Transfer of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled Thy1.1+ T cells revealed a larger population of CFSElow donor CD4 (Fig. 2f) and CD8 (data not shown) T cells in multiple host tissues at day 6 p.i. of high-dose infection in the absence of NK cells. There was also greater specific lysis of viral-peptide-coated target cells as detected by a conventional in vivo cytotoxicity assay at day 4 of infection (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, LCMV-specific Ly5.1+ TCR transgenic (P14) CD8 T cells (transfer 104) were recovered from tissues of NK-cell-depleted recipient (Ly5.2+) mice at two- to ninefold greater numbers than control-treated mice 6 days after low-dose infection (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together these results indicate that NK1.1+ cells repress the size of the antiviral T-cell response during LCMV infection.

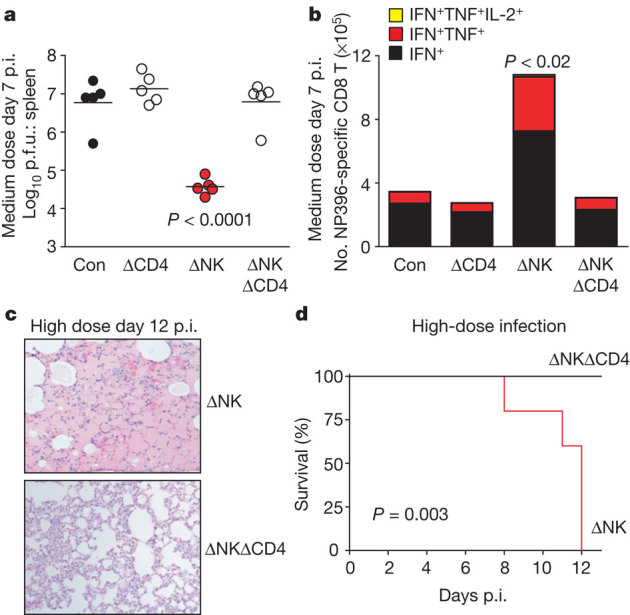

The activities of CD4 T cells are important for maintaining CD8 T-cell function during LCMV infection12,13,14. To assess whether CD4 T cells were involved in the NK-cell suppression of LCMV-specific CD8 T cells, mice were treated with antibodies to concurrently deplete both NK and CD4 T cells. Whereas depletion of NK cells before medium-dose LCMV infection resulted in a >200-fold reduction in splenic viral titres at day 7 p.i. relative to control and CD4-depleted (ΔCD4) mice (Fig. 3a), depletion of both NK and CD4 T cells (ΔNKΔCD4) had no effect on viral titres. The increase in the number of antiviral CD8 T cells producing more than one cytokine caused by NK-cell depletion was also prevented by co-depletion of CD4 T cells (Fig. 3b). In contrast, co-depletion of NK and CD8 T cells did not prevent an increase in IFN-γ+ LCMV epitope GP61–80-specific CD4 T cells (control: 3.8 ± 0.5% versus ΔNK: 9.8 ± 0.7% versus ΔNK/ΔCD8: 10.7 ± 1.6%, n = 3, P < 0.05 versus control) at day 12 of medium-dose infection.

Figure 3. Role of CD4 T cells in NK suppression of antiviral CD8 T cells, viral control and immunopathology.

a–e, Prior to medium- (a, b) or high-dose (c–e) infection, mice were injected with isotype (Con, control), anti-NK1.1 (ΔNK), anti-CD4 (ΔCD4), or both (ΔNKΔCD4). a, b, Viral titres in spleen (a) and number of cytokine-producing NP396–404-specific CD8 T cells (n = 5 per group, ± s.e.m.) in spleen at day 7 of medium-dose infection (b). c, d, H&E staining of lung (×100) (c) and survival at day 12 of high-dose infection (n = 3–5 per group) (d).

Paradoxically, at the high virus dose, co-depletion of NK and CD4 T cells prevented the severe pulmonary oedema (Fig. 3c) and increased mortality (Fig. 3d) associated with depletion of NK cells alone. In this experiment, mice were harvested on day 12 p.i., when three surviving NK-cell-depleted mice were moribund and required euthanasia, whereas all double-depleted mice showed relatively normal vigour. The livers of NK/CD4 double-depleted mice contained 25-fold more p.f.u. than livers from mice depleted of NK cells alone (NK: 5.7 ± 0.2 p.f.u. versus ΔNK/ΔCD4: 7.1 ± 0.1 p.f.u., n = 5, P < 0.0001). Enhancement of LCMV-specific CD8 T cells in the absence of NK cells was also abrogated by concurrent depletion of CD4 T cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). Together these data indicate that CD4 T cells are needed for NK-cell modulation of antiviral CD8 T-cell responses associated with viral clearance, persistence and immunopathology.

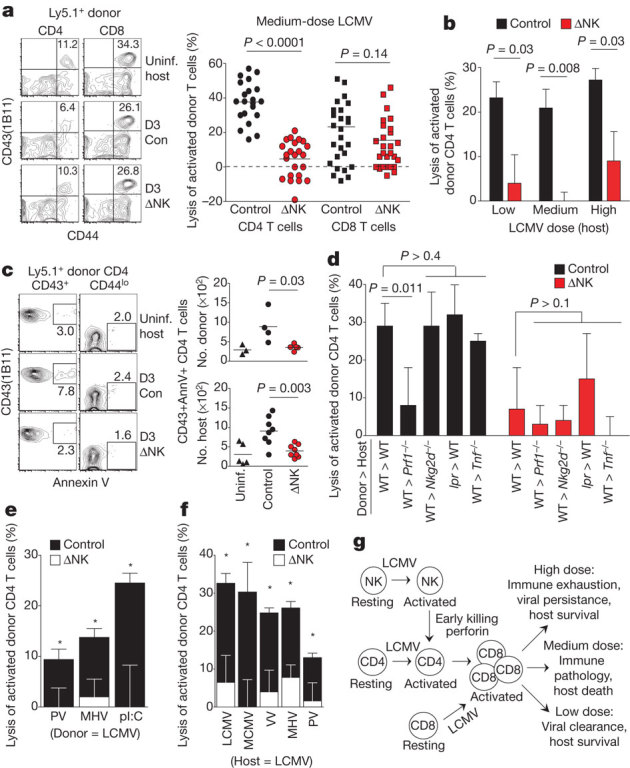

We used a modified in vivo cytotoxicity assay by injecting splenocytes from medium-dose-infected NK-cell-depleted mice (Ly5.1+, day 4 p.i.) into medium-dose-infected NK-cell-depleted (ΔNK) or isotype IgG2a-treated (control) recipient mice (Ly5.2+, day 3 p.i.). After 5 h, similar proportions of total donor T (control: 0.16 ± 0.03% versus ΔNK: 0.15 ± 0.02%, n = 21, P = 0.80) and B cells (control: 1.8 ± 0.2% versus ΔNK: 1.7 ± 0.2%, n = 21, P = 0.88) were recovered from infected recipients, regardless of NK-cell depletion. Likewise, recovery of activated (CD44hi CD43(1B11)+) donor CD8 T cells was similar from spleens of control and ΔNK mice, with minimal loss relative to uninfected control mice (Fig. 4a). In contrast, there was a substantial loss of activated donor CD4 T cells in infected relative to uninfected recipients, and this loss was prevented by depletion of NK cells (Fig. 4a). The magnitude of NK-cell-dependent loss of activated donor CD4 T cells was similar in low-, medium- and high-dose-infected recipients (Fig. 4b). More activated CD4 T cells, both donor and host derived, in infected (control) mice stained positively for the apoptosis indicator annexin V in comparison to naive donor CD4 T cells or to activated donor CD4 T cells in medium-dose-infected ΔNK recipient mice (Fig. 4c). In contrast to activated donor CD4 T cells, the recoveries of naive (CD44low) phenotype CD4 and CD8 donor T cells were not altered by NK-cell depletion (data not shown). These data indicate that NK cells in wild-type mice selectively and rapidly target activated CD4 T cells for elimination during LCMV infection.

Figure 4. NK cells rapidly eliminate activated CD4 T cells.

a–f, In vivo cytotoxicity assays were performed as described in Methods using donor cells from NK-cell-depleted wild-type (Ly5.1+) (a–f) or Faslpr (lpr) (d) mice 4 days p.i. with medium-dose LCMV (a–e) or other viruses (f). Recovery of donor T cells was examined 5 h after transfer into control or NK-depleted (ΔNK) Ly5.2+ mice (a, n = 21–28 per group; b–f, n = 3–5 per group). Host mice were uninfected or inoculated with medium-dose LCMV (day 3 p.i.) (a, c, d, f), various doses of LCMV (day 3 p.i.) (b), or PV (day 2), MHV (day 3) and polyI:C (pI:C) (day 1) (e). a, b, d–f, Lysis (mean ± s.e.m.) of donor T cells in infected relative to uninfected recipient mice; control versus ΔNK mice, *P < 0.05. WT, wild type. c, Annexin V reactivity of donor (Ly5.1+) and host (Ly5.1−) CD4 T cells. g, Proposed model connecting NK-cell killing of CD4 T cells to CD8 T cells and infection outcome in the presence of NK cells.

We next examined the involvement of NK-cell cytolytic mediators Fasl, TNF and perforin (Prf1) in this process. The loss of activated wild-type donor CD4 T cells in infected wild-type recipient mice (Fig. 4a, d) was seen when activated Faslpr (Fas mutant) mouse donor cells were transferred into wild-type recipient mice or when wild-type donor cells were transferred into Tnf−/− recipient mice (Fig. 4d). In contrast, there was relatively little loss of activated wild-type donor CD4 T cells in Prf1−/− hosts (Fig. 4d), whose retention of activated donor CD4 cells was not significantly different (P > 0.1) from that in NK-cell-depleted wild-type or Prf1−/− hosts. Thus, NK-cell elimination of activated CD4 T cells is mediated through a perforin-dependent pathway that does not require Fas or TNF.

Previous work has implicated NKG2D (also known as Klrk1) in targeting of activated T cells by murine NK cells in vitro15,16,17, but we observed no differences in activated wild-type donor CD4 T-cell survival in wild-type versus Nkg2d−/− recipients (Fig. 4d) or in wild-type mice treated with a blocking monoclonal antibody to NKG2D18 (data not shown). Of note is that we did not observe the expression of ligands for activating NK-cell receptors including NKG2D, NKp46 (also known as NCR1), DNAM-1 (also known as CD226) and TRAIL (also known as TNFSF10) on these early activated CD4 T cells, and NK-cell-mediated elimination of activated donor CD4 T cells also occurred in antibody-deficient (μMT−/−) mice (data not shown), precluding a role for antibody-dependent mechanisms. Activated CD4 T cells did, however, express much higher levels of adhesion molecules than naive cells, and these molecules have previously been shown to trigger NK-cell cytotoxicity via LFA-119,20. Somewhat surprising was the observation that the activated CD4 T cells were far more susceptible than activated CD8 T cells to direct killing by the NK cells, even though both expressed high levels of adhesion molecules. We previously had shown that the presence of the negatively signalling receptor CD244 (2B4) on NK cells prevented NK-cell-mediated lysis of activated CD8 T cells21. We found here that although expression of the CD244 ligand CD48 was upregulated on T cells after medium-dose LCMV infection, expression levels of CD48 were much higher on activated CD8 than on activated CD4 cells (mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD48: activated CD4, 3,423 ± 147; activated CD8, 6,180 ± 166; n = 9, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

To assess whether NK-cell-mediated lysis of activated CD4 T cells is a general principle of virus infections, we examined the loss of LCMV-activated CD4 T cells after transfer into mice inoculated with an unrelated Arenavirus, Pichinde virus (PV), the Coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), or the interferon inducer and NK-cell activator polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyI:C). All three stimuli induced measureable loss of activated donor CD4 T cells that was dependent upon the presence of NK cells (Fig. 4e). In reciprocal experiments, CD4 T cells activated during infection with PV, MHV, vaccinia virus (VV) or MCMV were lost upon transfer into mice infected with medium-dose LCMV when NK cells were present (Fig. 4f).

An analysis, by in vivo cytotoxicity assays after transfer into NK-cell-sufficient mice, of the window of time during which NK-cell regulation of T cells occurred in the LCMV medium-dose model showed reduced frequencies of activated donor CD4 T cells relative to uninfected recipients 1 (43%), 2 (32%), 3 (26%), 4 (4%) and 5 (8%) days after infection (Supplementary Fig. 8). The frequencies of activated donor CD4 T cells were increased by NK-cell depletion in recipient mice only at day 2 and day 3 p.i. These results indicate that NK cells target activated CD4 T cells mainly on the second and third day of infection, when the cytolytic activity of NK cells is at its peak22.

These results show that NK cells can have a crucial role in controlling virus-associated morbidity, mortality and persistence in the absence of direct NK-cell-mediated control of virus replication, and they do so by altering the numbers and polyfunctionality of virus-specific T cells. Their effect on activated CD4 T cells was presumably due to direct cytotoxicity, as demonstrated by rapid perforin-dependent elimination of activated CD4 T cells by NK cells in short-term in vivo cytotoxicity assays and the observation of enhanced annexin reactivity of CD4 T cells in the presence of NK cells. The effect of activated NK cells on CD8 T cells and virus clearance seemed to be indirect, and depended on the presence of CD4 T cells, which are known to produce factors that preserve CD8 T-cell viability and functionality12,13,23,24,25. This suggests a three-way interaction, whereby NK cells suppress the CD4 T-cell response, thereby preventing augmentation of the CD8 T-cell response, which, in turn, directly regulates viral clearance and immunopathology in this system (Fig. 4f).

Our observation of direct NK-cell-mediated lysis of T cells during virus infection is distinct from published accounts of NK-cell regulation of antiviral T cells during MCMV infection, in which NK-cell-mediated lysis of virus-infected cells contributes to control of viral burden and persistence of MCMV-infected dendritic cells that in turn regulate activity of antiviral T cells6,7,26. Moreover, we found no NK-cell-dependent changes in the number and antigen-presenting function of splenic dendritic cells during LCMV infection (Supplementary Fig. 9), consistent with our finding that NK cells directly regulated the T cells. A possible concern was that in vivo cellular depletion with antibodies against NK1.1 and CD4 have the potential to affect frequencies of NKT, γδ T and regulatory T cells, but the frequencies of these lymphocytes in the spleen of LCMV-infected mice were not altered after 3 to 4 days of infection by the low concentration of anti-NK1.1 used in these studies (Supplementary Figs 1 and 10). Moreover, depletion of NK cells in γδ T-cell-deficient (Tcrd−/− ) and NK T-cell-deficient (Cd1d−/− ) mice during medium-dose infection enhanced LCMV-specific T-cell responses and reduced viral loads (Supplementary Fig. 9), similar to that in wild-type mice. Therefore, these lymphocyte lineages seem to be dispensable for NK-cell immunoregulatory function during LCMV infection.

By adjusting the dose of the LCMV inocula, it is possible to generate diverse patterns of CD8 T-cell-regulated pathogenesis, similar to the variety of pathogenic patterns a human HCV infection can take, including rapid viral clearance, severe T-cell-dependent immunopathology and long-term persistence. We show here that at a high dose of LCMV, NK cells act beneficially by suppressing T-cell responses, thereby preventing severe pathology and mortality while enabling the development of a persistent infection from which mice eventually recover and clear the virus27. At the medium-dose inoculum, NK-cell suppression of T cells is detrimental to the host, as virus clearance is impaired due to the limited number and functionality of T cells. However, a medium dose of virus is not sufficient for complete clonal exhaustion of T cells, ultimately resulting in severe T-cell-dependent immunopathology that can lead to death of the host.

These results indicate that NK cells can serve as rheostats, or master regulators, of antiviral T-cell responses. Consistent with the fact that many virus infections induce cytokines that potently activate NK cells28, we found that NK-cell lysis of activated CD4 T cells was triggered by several viruses as well as after inoculation with polyI:C, which induces interferon and activates NK cells. Although a previous study found that NK-cell depletion did not alter the magnitude of antiviral T-cell responses during infection with the Armstrong strain of LCMV29, we have observed enhanced antiviral T-cell responses and improved viral control at early time points after infection of NK-cell-depleted mice with both LCMV Armstrong and Pichinde virus (S.N.W., unpublished observations). Thus, the timing and the type of evaluation may be important to detect detrimental effects of NK cells on T cells during more benign viral infections.

Methods Summary

Infection model

One day before infection, male C57BL/6 mice were selectively depleted of NK cells through a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 25 μg anti-NK1.1 monoclonal antibody (PK136) or a control mouse IgG2a (both from Bio-X-Cell), as previously described21 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In some cases, mice were also depleted of CD4 T cells by i.p. injection of 100 μg anti-CD4 (GK1.5) at days −1 and +3 of infection. Mice were then infected i.v. with 5 × 104 (low dose), 2 × 105 (medium dose) or 2 × 106 (high dose) p.f.u. of the clone 13 variant of LCMV. Virus was titrated by plaque assay on Vero cells. In some experiments, mice were inoculated i.p. with 1.5 × 107 p.f.u. of PV, 8 × 105 p.f.u. of MHV strain A59, 1 × 106 p.f.u. of VV strain Western Reserve, 1 × 106 p.f.u. of Smith strain MCMV, or 200 μg of polyI:C (Invivogen).

Immune assays

The number of LCMV-specific T cells was measured by H-2Db-NP396–404 tetramer staining or by intracellular cytokine staining after 5 h ex vivo stimulation with 1 μM viral peptide in the presence of brefeldin A. T-cell cytolytic activity was measured in vivo as described previously21.

In vivo NK-cell assay

An unconventional in vivo cytotoxicity assay was previously established to determine NK-cell killing of lymphocyte populations21. Donor mice were depleted of NK cells and then infected i.v. or i.p. with different viruses. At day 4 p.i., single-cell splenocyte suspensions were prepared from these mice, labelled with 2 μM CFSE, and transferred (2 × 107) into various strains of NK-cell-depleted or control recipient mice that were either uninfected or had been infected with virus 1–5 days previously. Spleens of recipient mice were harvested 5 h after transfer and assessed for survival of donor T cells.

Online Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, Thy1.1+, Tcrd−/− , Tcrb−/− , Faslpr, Prf1−/− and μMT−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. Ly5.1+ mice were from Taconic Farms. Nkg2d−/− and Cd1d−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were obtained from B. Polić30 and M. Exley31, respectively. Congenic (Ly5.1+) TCR transgenic P14 (ref. 32) mice and Tnf−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were bred at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS). Male mice at 6–16 weeks of age were routinely used in experiments. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were performed in compliance with institutional guidelines as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UMMS.

Virus infections and in vivo cell depletions

The clone 13 variant of LCMV was propagated in baby hamster kidney BHK21 cells9 and titrated by plaque assay on Vero cells. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 104 (low dose), 2 × 105 (medium dose), or 2 × 106 (high dose) p.f.u. of LCMV. Selective depletion of NK cells was achieved through a single i.p. injection of 25 μg anti-NK1.1 monoclonal antibodies (PK136) or a control mouse IgG2a produced by Bio-X-Cell, as previously described21 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Alternatively, mice received a carefully titrated dose of 10 μl of anti-asialo GM1 antibody (Wako Biochemicals) diluted in 200 μl PBS i.p. 1 day before virus infection. Anti-NKG2D monoclonal antibody (CX5) was a gift of L. Lanier, and 200 μg was injected i.p. at the time of infection. Mice were depleted of T cells by i.p. injection of either 100 μg anti-CD4 (GK1.5) or 50 µg anti-CD8 (2.43) produced by Bio-X-Cell at day −1 and day +3 of infection. In some experiments, mice were inoculated i.p. with 1.5 × 107 p.f.u. of PV, 8 × 105 p.f.u. of MHV strain A59, 1 × 106 p.f.u. of VV strain Western Reserve, 1 × 106 p.f.u. of Smith strain MCMV, or 200 μg of polyI:C (Invivogen).

Tetramers and peptides

T-cell epitopes encoded by LCMV include NP396–404 (FQPQNGQFI), GP33–41 (KAVYNFATC) and GP61–80 (GLKGPDIYKGVYQFKSVEFD)33,34,35. Peptides were purchased from 21st Century Biochemicals and purified by reverse phase-HPLC to 90% purity. H-2Db-NP396–404 tetramers were prepared as described36. CD1d-PBS57-allophycocyanin tetramers provided by NIAID Tetramer Facility were a gift from L. Berg.

Antibodies and FACS analysis

Fluorescently labelled antibodies and reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences, eBioscience, BioLegend and R&D Biosystems. Flow cytometric analyses of cells were performed on a LSR II cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with FACSDiva software and data were analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

CFSE labelling and adoptive transfer

Spleens from donor mice were mechanically disrupted, and erythrocytes were lysed using a 0.84% NH4Cl solution in order to generate single-cell leukocyte suspensions. Cells were labelled for 15 min at 37 °C with the 2 µM fluorescent dye CFSE (CFDA-SE, Molecular probes), washed, and transferred i.v. (3 × 107 cells) to recipient mice.

In vivo cytotoxicity assays

T-cell cytolytic activity was measured in vivo as described previously21. Briefly, single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens of uninfected mice, and separate fractions of cells were then loaded with LCMV peptides (1 µM) for 45 min at 37 °C before labelling with CFSE (2.5, 1 or 0.4 µM, Molecular Probes) for 15 min at 37 °C. After washing, these populations were combined at equal ratios and transferred i.v. into either naive or infected recipients. Survival of each transferred population in the spleens of recipient mice was assessed 16 h after transfer. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: 100 − ((% LCMV target population in infected experimental/% unlabelled population in infected experimental) ÷ (% LCMV target population in naive control/% unlabelled population in naive control)) × 100).

An unconventional in vivo cytotoxicity assay was previously established to determine NK-cell killing of lymphocyte populations in vivo21. Wild-type or Faslpr donor mice were depleted of NK cells and then infected with VV, MCMV, MHV, PV, or a medium dose of LCMV clone 13. At day 4 p.i., single cell splenocyte suspensions were prepared from these mice, labelled with CFSE, and then transferred (2 × 107) into experimental recipient mice on day 3 of medium dose LCMV infection, unless otherwise noted. Recipients included WT, Prf1−/−, Tnf−/− , or Nkg2d−/− mice that were administered anti-NK1.1 or isotype control antibodies one day before inoculation with PV, MHC, polyI:C, or various doses of LCMV clone 13. Some recipient mice were uninfected and served as controls. Spleens of recipient mice were harvested 5 h after transfer and assessed for survival of donor T cells.

In vitro antigen presentation assay

Stimulator cells were prepared by isolation of single-cell suspensions from the spleens of uninfected as well as isotype-treated or anti-NK1.1-treated mice infected 3 days previously with a medium dose of LCMV i.v. Following irradiation, stimulator cells (5 × 104) were plated at a 1:10 ratio with CFSE-labelled Ly5.1+ LCMV-specific P14 CD8 T cells (5 × 105) in T-cell stimulation medium (RPMI supplemented with 100 U ml−1 penicillin G, 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin sulphate, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% heat-inactivated (56 °C, 30 min) FBS), which was refreshed every 2 days. P14 cells were enumerated and analysed for dilution of CFSE as a measure of proliferation every 24 h after initiation of co-culture.

Lymphocyte preparation and intracellular cytokine assay

Single-cell leukocyte suspensions from spleens, inguinal lymph nodes, lung and liver were prepared as described previously21 and were plated at 2 × 106 cells per well in 96-well plates. Cells were stimulated for 5 h at 37 °C with either 1 µM viral peptide or 2.5 µg ml−1 anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody in the presence of brefeldin A and 0.2 U ml−1 rhIL-2. Stimulated cells were then pre-incubated with a 1:200 dilution of Fc Block (2.4G2) in FACS buffer (HBBS, 2% FCS, 0.1% NaN3) and stained for 20 min at 4 °C with various combinations of fluorescently tagged monoclonal antibodies. After washing, cells were permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution and then stained in BD Permwash using monoclonal antibodies specific for various cytokines. AnnexinV staining was performed in azide-free FACS buffer directly ex vivo according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Results are routinely displayed as mean ± s.e.m., with statistical differences between experimental groups determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, where a P value of <0.05 was deemed significant. Statistical differences in survival were determined by log rank (Mantel–Cox) analysis. Graphs were produced and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism.

Supplementary information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-10 with legends. (PDF 691 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Hearn, C. Baer, J. Suschak and P. Afriyie for technical support; K. Daniels and M. Seedhom for insightful discussions; R. Taniguchi and V. Kumar for sharing unpublished observations; and H. Ducharme for mouse husbandry. We thank L. Berg for NKT tetramer, L. Lanier for anti-NKG2D blocking antibody (CX5), B. Polić for Nkg2d−/− mice and M. Exley for Cd1d−/− mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant AI07349 (S.N.W.) and research grants AI-17672, AI-081675, CA34461 (R.M.W.), AI46578 (L.K.S.), a German Research Foundation fellowship CO310-2/1 (M.C.) and an institutional Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (DERC) grant DK52530. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily express the views of the NIH.

PowerPoint slides

Author Contributions

S.N.W. designed the study, performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript; R.M.W. designed the study, analysed data and wrote the manuscript; M.C. and L.K.S. were involved in study design, discussed results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Martin MP, et al. Epistatic interaction between KIR3DS1 and HLA-B delays the progression to AIDS. Nature Genet. 2002;31:429–434. doi: 10.1038/ng934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennes W, et al. Cutting edge: resistance to HIV-1 infection among African female sex workers is associated with inhibitory KIR in the absence of their HLA ligands. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6588–6592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khakoo SI, et al. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2004;305:872–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1097670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter G, et al. HIV-1 adaptation to NK-cell-mediated immune pressure. Nature. 2011;476:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature10237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukowski JF, Woda BA, Habu S, Okumura K, Welsh RM. Natural killer cell depletion enhances virus synthesis and virus-induced hepatitis in vivo. J. Immunol. 1983;131:1531–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins SH, et al. Natural killer cells promote early CD8 T cell responses against cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews DM, et al. Innate immunity defines the capacity of antiviral T cells to limit persistent infection. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1333–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welsh RM, Brubaker JO, Vargas-Cortes M, O’Donnell CL. Natural killer (NK) cell response to virus infections in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. The stimulation of NK cells and the NK cell-dependent control of virus infections occur independently of T and B cell function. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1053–1063. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler LD, Chiller JM, Oldstone MB. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J. Exp. Med. 1984;160:521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zajac AJ, et al. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Yogeeswaran G, Bukowski JF, Welsh RM. Expression of asialo GM1 and other antigens and glycolipids on natural killer cells and spleen leukocytes in virus-infected mice. Nat. Immun. Cell Growth Regul. 1985;4:21–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battegay M, et al. Enhanced establishment of a virus carrier state in adult CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice. J. Virol. 1994;68:4700–4704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4700-4704.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matloubian M, Concepcion RJ, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J. Virol. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller MJ, Khanolkar A, Tebo AE, Zajac AJ. Maintenance, loss, and resurgence of T cell responses during acute, protracted, and chronic viral infections. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4204–4214. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noval Rivas M, et al. NK cell regulation of CD4 T cell-mediated graft-versus-host disease. J. Immunol. 2010;184:6790–6798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabinovich BA, et al. Activated, but not resting, T cells can be recognized and killed by syngeneic NK cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3572–3576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soderquest K, et al. Cutting edge: CD8+ T cell priming in the absence of NK cells leads to enhanced memory responses. J. Immunol. 2011;186:3304–3308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogasawara K, et al. NKG2D blockade prevents autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Immunity. 2004;20:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naganuma H, et al. Increased susceptibility of IFN-γ-treated neuroblastoma cells to lysis by lymphokine-activated killer cells: participation of ICAM-1 induction on target cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1991;47:527–532. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber DF, Faure M, Long EO. LFA-1 contributes an early signal for NK cell cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 2004;173:3653–3659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waggoner SN, Taniguchi RT, Mathew PA, Kumar V, Welsh RM. Absence of mouse 2B4 promotes NK cell-mediated killing of activated CD8+ T cells, leading to prolonged viral persistence and altered pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:1925–1938. doi: 10.1172/JCI41264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welsh RM., Jr Cytotoxic cells induced during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection of mice. I. Characterization of natural killer cell induction. J. Exp. Med. 1978;148:163–181. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1572–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1175194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frohlich A, et al. IL-21R on T cells is critical for sustained functionality and control of chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1172815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.1174182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bukowski JF, Woda BA, Welsh RM. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection in natural killer cell-depleted mice. J. Virol. 1984;52:119–128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.119-128.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldstone MB. Biology and pathogenesis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;263:83–117. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56055-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsh RM. Regulation of virus infections by natural killer cells. Nat. Immun. Cell Growth Regul. 1986;5:169–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su HC, et al. NK cell functions restrain T cell responses during viral infections. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:3048–3055. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<3048::AID-IMMU3048>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zafirova B, et al. Altered NK cell development and enhanced NK cell-mediated resistance to mouse cytomegalovirus in NKG2D-deficient mice. Immunity. 2009;31:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Exley MA, et al. Innate immune response to encephalomyocarditis virus infection mediated by CD1d. Immunology. 2003;110:519–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2003.01779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pircher H, et al. T cell tolerance to Mlsa encoded antigens in T cell receptor V beta 8.1 chain transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1989;8:719–727. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Most RG, et al. Identification of Db- and Kb-restricted subdominant cytotoxic T-cell responses in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice. Virology. 1998;240:158–167. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oxenius A, et al. Presentation of endogenous viral proteins in association with major histocompatibility complex class II: on the role of intracellular compartmentalization, invariant chain and the TAP transporter system. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:3402–3411. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klavinskis LS, Whitton JL, Joly E, Oldstone MB. Vaccination and protection from a lethal viral infection: identification, incorporation, and use of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte glycoprotein epitope. Virology. 1990;178:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90336-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mylin LM, et al. Quantitation of CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses to multiple epitopes from simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen in C57BL/6 mice immunized with SV40, SV40 T-antigen-transformed cells, or vaccinia virus recombinants expressing full-length T antigen or epitope minigenes. J. Virol. 2000;74:6922–6934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.15.6922-6934.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-10 with legends. (PDF 691 kb)