Abstract

The potential therapeutic benefits associated with Hsp90 modulation for the treatment of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases highlight the importance of identifying novel Hsp90 scaffolds. KU-398, a novobiocin analogue, and silybin were recently identified as new Hsp90 inhibitors. Consequently, a library of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives that incorporated the structural features of KU-398 and silybin was designed, synthesized, and evaluated against two breast cancer cell lines. Western blot analysis confirmed that the resulting 3-arylcoumarin hybrids target the Hsp90 protein folding machinery.

Keywords: heat shock protein 90, Hsp90 inhibitors, novobiocin, silybin, 3-arylcoumarin, breast cancer

The 90 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) is an ATP-dependent chaperone that is responsible for the folding, activation, and stabilization of more than 200 client proteins, of which approximately 50 are kinases, hormone receptors, and/or transcription factors directly associated with signaling pathways that regulate cell growth.1,2 Hsp90 exists as a homodimer in normal cells and acts as a house-keeping chaperone to maintain protein homeostasis.3 However, in malignant cells, Hsp90 forms a superchaperone complex that binds to cochaperones and immunophilins to modulate the function of proteins associated with all six hallmarks of cancer. These oncogenic Hsp90-dependent clients include Raf-1, Akt, CDK4, Src, hTERT, and c-Met, all of which have developed an addiction to Hsp90 for their activity in transformed cells.4,5 Not surprisingly, inhibition of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery results in simultaneous disruption of these signaling cascades and induces client protein degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which can eventually lead to cell death.6,7 More than 16 small molecule inhibitors that target the Hsp90 N-terminus are under clinical evaluation in an effort to validate Hsp90 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer.8,9 During Hsp90 N-terminal inhibition, induction of the pro-survival heat shock response also occurs at the same concentration needed to promote client protein degradation, which can often lead to cytostatic activity in lieu of cytotoxicity. Ideally, it would be beneficial to segregate these two activities so that one can induce client protein degradation, without inducing a pro-survival pathway for the treatment of cancer or, conversely, induce the pro-survival pathways to aid cells exposed to toxic insults without causing client protein degradation, such as those found in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Prion, and Hodgkin's diseases.10−12 The existing and emerging therapeutic benefits associated with Hsp90 modulation highlight the importance of identifying novel Hsp90 inhibitors that can differentiate these attributes.

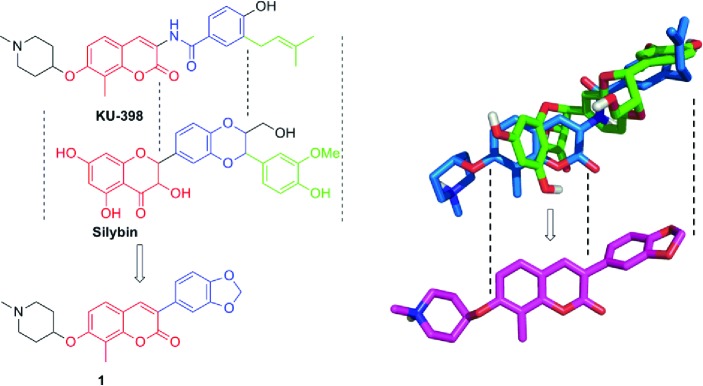

Hsp90 inhibitors for the treatment of cancers are under extensive investigation, and recently, a lead molecule named KU-398 was shown to exhibit promising anticancer activity.13−19 Alongside KU-398, the natural product, silybin, was also recently identified as an Hsp90 inhibitor through an Hsp90-dependent firefly luciferase rematuration and Hsp90-dependent heme-regulated eIF2α kinase (HRI) activation assay.20 These studies suggested that similar to KU-398, silybin also binds to the Hsp90 C-terminus. Structural alignment of KU-398 and silybin suggests that the coumarin and flavonone ring systems may be interchangeable (Figure 1) and that the corresponding 3-arylcoumarin derivatives could target the Hsp90 protein folding machinery. Interestingly, 3-aryl-containing coumarins are commonly produced by plants and often exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities, but more recently, they were shown to also manifest anticancer activity.21−24 As a consequence of these observations, compound 1 was designed to maintain the coumarin ring present in KU-398 while incorporating the 3-aryl appendage of silybin to provide a new class of Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Rationale for the design of 3-arylcoumarin 1. Left: Structural alignment of KU-398 and silybin. Right: Overlay of energy minimized KU-398 (blue) with silybin (green).

Synthesis of compound 1 commenced with commercially available 2-methyl resorcinol (2), which was formylated under Vilsmeier–Haack conditions using phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), followed by hydrolysis to give formyl-resorcinol 3 (Scheme 1).25 Condensation of 3 with 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylacetic acid in the presence of acetic anhydride and pyridine produced the acylated 3-arylcoumarin, 5, which upon hydrolysis of the ester yielded compound 6. Finally, a Mitsunobu etherification proceeded upon treatment of 6 with N-methyl-4-hydroxylpiperidine to afford 3-arylcoumarin, 1.17

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 3-Arylcoumarin 1.

Biological evaluation of 3-arylcoumarin 1 for anti-proliferative activity against SKBr3 (estrogen receptor negative, Her2 overexpressing breast cancer cells) and MCF-7 (estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells) cell lines was performed.18 Because Her2 and the estrogen receptor are two Hsp90-dependent client proteins and their stability and function are highly dependent upon Hsp90 folding machinery, studies with these two different cell lines were used. Compound 1 was shown to manifest anti-proliferative activity with an IC50 value of 5.21 ± 1.14 μM against SKBr3 cells and 3.71 ± 0.11 μM against MCF-7 cells. Western blot analyses of MCF-7 cell lysates confirmed selective degradation of Hsp90-dependent clients at concentrations that parallel the observed anti-proliferative activity (Figure 2), suggesting that 3-arylcoumarin derivatives target the Hsp90 protein folding machinery.

Figure 2.

Western blot analyses of Hsp90-dependent client proteins from MCF-7 breast cancer cell lysates upon treatment with 3-arylcoumarin 1 for 24 h. Concentrations (in μM) were indicated above each lane, and geldanamycin (G, 0.5 μM) and dimethylsulfoxide (D) were employed as positive and negative controls.

To generate structure–activity relationships for the phenyl appendage, commercially available coumarin 8, which lacks the 8-methyl substituent, was used. Bromination of 8 proceeded poorly following literature procedures.26−28 Therefore, compound 8 was first methylated with iodomethane in the presence of sodium hydride in DMF to afford compound 9, which underwent bromination with N-bromosuccinimide in the presence of catalytic sodium acetate. Subsequent demethylation of 10 with tribromoborane, followed by Mitsunobu coupling with N-methyl-4-hydroxylpiperidine, generated intermediate 12. The final products were then produced by Suzuki coupling of 12 with a series of phenylboronic acids (13a–p) or fused heteroarylbronic acids (15a,b) to give a library of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives, 14a–p and 16a,b (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 3-Arylcoumarins.

Upon construction of this library, the corresponding 3-arylcoumarins were evaluated for anti-proliferative activity against SKBr3 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. As shown in Table 1, 3-arycoumarin derivatives are more efficacious against MCF-7 than SKBr3 cells. Any substitution on the phenyl ring was determined beneficial; however, electron-deficient groups are more effective than electron-rich substitutions (14d/14h vs 14f). Substitution at the para position resulted in a slightly increased activity as compared to substitutions at the meta position (14d vs 14c), while substitution at the ortho position is detrimental (14b vs 14d and 14o vs 14p). It appears that bulky substitutions (14n) or a phenoxyl group (14m) at the para position can also lead to compounds that exhibit increased anti-proliferative activity. The decreased activity observed for 14l, when compared to compound 1, clearly demonstrates that a methyl group at the 8-position of the coumarin ring increases anti-proliferative activity. More interestingly, benzo[b]thiophene derivative 16a exhibited activity against both cell lines at concentrations below 1 μM and could serve as a lead compound for further diversification.

Table 1. Anti-proliferative Activity for 3-Arylcoumarin Derivatives.

| R | SKBr3 (μM) | MCF-7 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14a | H | 38.41 ± 2.31a | 28.98 ± 14.96 |

| 14b | o-Cl | 25.38 ± 9.24 | 10.58 ± 1.50 |

| 14c | m-Cl | 9.46 ± 0.84 | 5.79 ± 0.53 |

| 14d | p-Cl | 8.24 ± 1.59 | 3.89 ± 0.61 |

| 14e | p-CH3 | 11.23 ± 1.11 | 8.60 ± 0.25 |

| 14f | p-OCH3 | 29.93 ± 15.44 | 16.92 ± 2.34 |

| 14g | m-CF3 | 9.21 ± 1.67 | 4.64 ± 0.69 |

| 14h | p-OCF3 | 5.78 ± 0.59 | 4.12 ± 0.37 |

| 14i | m-CN | 10.60 ± 1.27 | 8.42 ± 0.12 |

| 14j | p-F | 43.85 ± 0.32 | 10.50 ± 0.57 |

| 14k | m-F | 24.86 ± 9.72 | 7.67 ± 1.46 |

| 14l | 3,4-methylenedioxyl | 14.80 ± 0.01 | 8.79 ± 1.32 |

| 14m | p-phenoxy | 4.43 ± 0.14 | 1.45 ± 0.11 |

| 14n | p-t-butyl | 4.42 ± 1.75 | 2.36 ± 0.30 |

| 14o | o-phenyl | 15.63 ± 4.35 | 15.62 ± 0.50 |

| 14p | p-phenyl | 3.33 ± 0.69 | 3.08 ± 0.09 |

| 16a | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | |

| 16b | 5.84 ± 0.06 | 4.93 ± 0.06 |

Values represent means ± standard deviations for at least two separate experiments performed in triplicate.

To further confirm that 8-methyl substituents are beneficial for anti-proliferative activity, a small set of commercial available phenylacetic acids 17a–e were similarly condensed with 3 in the presence of acetic anhydride, followed by hydrolysis to give 19a–e, which underwent etherication with N-methyl-4-hydroxylpiperidine to afford 8-methyl-3-arylcoumarin derivatives, 20a–e (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 8-Methyl-3-arylcoumarins.

As suggested by related compounds, the 8-methyl-3-arylcoumarin derivatives manifested improved anti-proliferative activity, when compared to the 8-desmethyl analogues against the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, suggesting that substitution at the 8-position of the coumarin ring is important (Table 2). Although compound 14f, which contains an electron-rich methoxy group at the para position, exhibited decreased activity when compared to 8-desmethyl compounds against both SKBr3 and MCF-7 cell lines (see Table 1), its 8-methyl counterpart (20b) manifested comparable activity to the other 8-methyl derivatives (20c–e).

Table 2. Anti-proliferative Activity for 8-Methyl-3-arylcoumarins.

| R | SKBr3 (μM) | MCF-7 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | H | 14.27 ± 0.54a | 7.72 ± 1.64 |

| 20b | p-OCH3 | 5.52 ± 1.44 | 1.97 ± 0.11 |

| 20c | p-Cl | 4.94 ± 0.03 | 1.24 ± 0.06 |

| 20d | p-F | 7.38 ± 0.23 | 3.83 ± 0.00 |

| 20e | p-OCF3 | 4.51 ± 0.42 | 1.65 ± 0.16 |

Values represent means ± standard deviations for at least two separate experiments performed in triplicate.

The 3-benzo[b]thiophenecoumarin 16a exhibited the most potent anti-proliferative activity against two breast cancer cell lines evaluated. The anti-proliferative activities exhibited by 16a result from Hsp90 inhibition as demonstrated by Western blot analyses of MCF-7 cell lysates following administration of 16a. As shown in Figure 3, the Hsp90-dependent client proteins, Raf-1 and Akt, were degraded in a concentration-dependent manner when exposed to 16a, which mirrored the concentration needed to manifest anti-proliferative activity and therefore linked client protein degradation to cell viability. The non-Hsp90-dependent protein, actin, was not affected upon administration of 16a, indicating that non-Hsp90-dependent proteins are not degraded. In addition, Hsp90 levels appear to decrease at increasing concentrations of 16a, which is consistent with other known Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitors.29

Figure 3.

Western blot analyses of MCF-7 cell lysates for Hsp90 client protein degradation after 24 h of incubation. Concentrations (in μM) of 16a are indicated above each lane. Geldanamycin (G, 500 nM) and DMSO (D) were employed, respectively, as positive and negative controls.

In conclusion, a library of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives was designed, synthesized, and evaluated against two breast cancer cell lines, and the initial structure–activity relationships for the phenyl appendage were investigated. 3-Arylcoumarin derivatives were identified as novel inhibitors of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery. Compound 16a exhibited lead like activity, and Western blot analyses of this compound supports binding to the Hsp90 C-terminus, as no increase in Hsp90 levels was observed. Further structural modifications are currently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures for the synthesis and characterization of new compounds (1H and 13C NMR, HRMS). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

We gratefully acknowledge support of this project by the NIH/NCI (CA120458).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Blagg B. S. J.; Kerr T. D. Hsp90 inhibitors: Small molecules that transform the Hsp90 protein folding machinery into a catalyst for protein degradation. Med. Res. Rev. 2006, 26, 310–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D.http://www.picard.ch/downloads/Hsp90interactors.pdf.

- Taipale M.; Jarosz D. F.; Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 515–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P. Altered states: Selectively drugging the Hsp90 cancer chaperone. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P.; Burrows F.; Neckers L.; Rosen N. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic expolitation on oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1113, 202–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Burrows F. Targeting multiple signal transduction pathways through inhibition of Hsp90. J. Mol. Med. 2004, 82, 488–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S.; Alarcon S. V.; Lee S.; Lee M. J.; Giaccone G.; Neckers L.; Trepel J. B. Update on Hsp90 inhibitors in clinical trial. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biamonte M. A.; Van de Water R.; Arndt J. W.; Scannevin R. H.; Perret D.; Lee W. C. Heat Shock Protein 90: Inhibitors in Clinical Trials. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2332–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L. B.; Blagg B. S. J. To fold or not to fold: modulation and consequences of Hsp90 inhibition. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 267–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W. J.; Sun W. L.; Taldone T.; Rodina A.; Chiosis G. Heat shock protein 90 in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo K. A. Targeting HSP90 to halt neurodegeneration. Chem. Biol. 2006, 13, 115–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly A. C.; Mays J. R.; Burlison J. A.; Nelson J. T.; Vielhauer G.; Holzbeierlein J.; Blagg B. S. J. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of coumarin ring derivatives of the novobiocin scaffold that exhibit anti-proliferative activity. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8901–8920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlison J. A.; Neckers L.; Smith A. B.; Maxwell A.; Blagg B. S. J. Novobiocin: redesigning a DNA gyrase inhibitor for selective inhibition of Hsp90. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 15529–15536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. M.; Shen G.; Neckers L.; Blake H.; Holzbeierlein J.; Cronk B.; Blagg B. S. J. Hsp90 inhibitors identified from a library of novobiocin analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12778–12779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly A. C.; Zhao H. P.; Kusuma B. R.; Blagg B. S. J. Cytotoxic sugar analogues of an optimized novobiocin scaffold. Med. Chem. Commun. 2010, 1, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. P.; Kusuma B. R.; Blagg B. S. J. Synthesis and evaluation of noviose replacements on novobiocin that manifest anti-proliferative activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 311–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. P.; Donnelly A. C.; Kusuma B. R.; Brandt G. E. L.; Brown D.; Rajewski R. A.; Vielhauer G.; Holzbeierlein J.; Cohen M. S.; Blagg B. S. J. Engineering an antibiotic to fight cancer: optimization of the novobiocin scaffold to produce anti-proliferative agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3839–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlison J. A.; Avila C.; Vielhauer G.; Lubbers D. J.; Holzbeierlein J.; Blagg B. S. J. Development of novobiocin analogues that manifest anti-proliferative activity against several cancer cell lines. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2130–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. P.; Brandt G. E.; Galam L.; Matts R. L.; Blagg B. S. J. Identification and initial SAR of silybin: an Hsp90 inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 2659–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demizu S.; Kajiyama K.; Takahashi K.; Hiraga Y.; Yamamoto S.; Tamura Y.; Okada K.; Kinoshita T. Antioxidant and antimicrobial constituents of licorice—isolation and structure ellucidation of a new benzofuran derivative. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 3474–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Seedi H. R. Antimicrobial arylcoumarins from Asphodelus microcarpus. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai T.; Marumo A.; Kaitou K.; Kanda T.; Terada S.; Nomura T. Anti-helicobacter pylori flavonoids from licorice extract. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 1449–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L. S.; An R.; Wang X. H.; Li Y. M. Discovery of novel osthole derivatives as potential anti-breast cancer treatment. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7426–7428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L. B.; Blagg B. S. J. Click chemistry to probe Hsp90: synthesis and evaluation of a series of triazole-containing novobiocin analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3957–3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B.; Venkateswarlu K.; Majhi A.; Siddaiah V.; Reddy K. R. A facile nuclear bromination of phenols and anilines using NBS in the presence of ammonium acetate as a catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 267, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly N. C.; De P.; Dutta S. Mild regioselective monobromination of activated aromatics and hetero-aromatics with N-bromosuccinimide in tetrabutylammonium bromide. Synthesis-Stuttgart 2005, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswarlu K.; Suneel K.; Das B.; Reddy K. N.; Reddy T. S. Simple catalyst-free regio- and chemoselective monobromination of aromatics using NBS in polyethylene glycol. Synth. Commun. 2009, 39, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.; Kim S. A.; Choi H. S.; Yoon J. H.; Ahn S. G. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses the expression of HSP70 and HSP90 and exhibits anti-tumor activity in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.