Abstract

Novel fluorescent dyes with ultra pseudo-Stokes Shift were prepared based on intramolecular energy transfer between a fluorescent donor and a Cyanine-7 acceptor. The prepared dyes could be excited at ~ 320 nm and emit fluorescence at ~ 780 nm. The energy transfer efficiencies of the system are found to be > 94 %.

Keywords: Ultra Pseudo-Stokes Shift (UPSS), Energy Transfer, Cyanine-7 Dyes, 7-hydroxycoumarine, benzothiazole

Heptamethine dyes (Cy-7) are one of the favorable fluorescent probes used for molecular imaging in biotechnology field.1–3 This is due to their emission wavelength being in the 750–850 nm near-infrared (NIR) region, where biological tissues have little background autofluorescence. However, most of the heptamethine dyes have a major drawback that their Stokes shifts are small, usually less than 20 nm. Small Stokes shifts cause errors in fluorescence measurement because of the overlapping of exciting and emission spectra, instigating a need to develop special dyes with large Stokes shifts. Amino Cy-7 dyes (Figure 1a) have Stokes shifts in the range of 50–150 nm due to the excited state intramolecular charge transfer, therefore they have been applied to multispectral NIR imaging both in vitro and in vivo.4, 5, 6 However, their fluorescence is closely dependent on solvent viscosity and pH, thus the fluorescence could be completely lost under extreme physiological pH environments.7 Resulting from this, many NIR pH probes based on amino Cy-7 have been developed for intracellular pH imaging.2, 8 Unfortunately, photo instability of this type of dyes has also been documented.5, 9 More recently, a large pseudo Stokes shift Cy-7 dye (Figure 1b) based on through-bond energy transfer has been developed and applied to label cells.10 In their design, the asymmetrical Cy-7 was conjugated to a TM-BODIPY donor using a palladium catalyzed coupling reaction. The preparation required multiple steps of complicated synthesis which could be time consuming. Its energy transfer efficiency (ETE) from BODIPY donor to the Cy-7 dye acceptor is around 40%, more than half of the energy was lost via non-emission decay.

Figure 1.

Two known types of large Stokes shift Cy-7

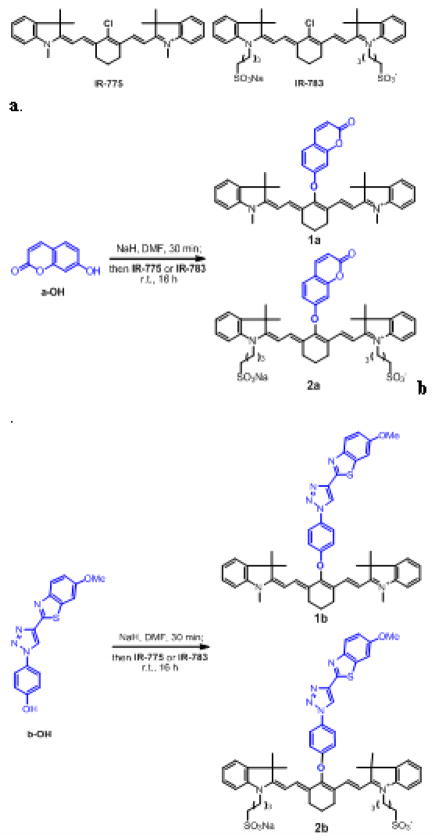

In this study, a facile approach to synthesize ultra pseudo-Stokes shift (UPSS) dyes (Scheme 1), up to 479 nm, was developed. The Cy-7 containing UPSS dyes were designed to have two closely placed fluorescent donor and acceptor (which are separated through one single C-O bond), so that intramoleculal energy transfer could be occurred efficiently,11, 12 when excitation energy was applied to the donor. The pseudo-Stokes shift was determined by the wavelength difference between the donor absorption and the acceptor emission. A large pseudo-Stokes shift of the UPSS dyes offer clear intracellular imaging fluorescence signal due to the elimination of cell autofluorescence and excitation scattering. These UPSS dyes were prepared conveniently by coupling reactive Cy-7 dyes, IR-775 or IR-783, with commercially available 7-hydroxycoumarin or a benzothiazole fluorophore b-OH, developed by our group.13 Importantly these UPSS dyes offer not only large pseudo Stokes shift in the range of 462–479 nm, but also extremely high energy transfer efficiency, > 94%.

Scheme 1.

Structure of Cy-7 dyes, and synthetic scheme of UPSS dyes1a–b, and 2a–b. Donors and acceptors are in blue and black, respectively.

A starting material, compound b-OH, was prepared as previously published13 and the detailed synthesis was described in the supporting information. The synthesis of UPSS dyes 1a–b and 2a–b was straight forward as shown in scheme 1. Each product was synthesized via a two-step, one pot reaction. First, the phenol, a-OH or b-OH, was deprotonated with NaH in demethylformamide (DMF) to form the sodium phenolate, which was then reacted with commercially available chlorosubstituted IR-775 or -783 overnight at room temperature to afford the desired products in good to moderate yields respectively. The compounds 1a14 and 1b synthesized from IR-775 were purified by chromatography on silica. For reactions involving IR-783, the resulting water soluble products 2a and 2b containing polar sulfonate groups were purified by reverse-phase high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). All the compounds were characterized by 1H NMR and HRMS.

The UV-visible absorption spectra of 1a–b and 2a–b have two maxima corresponding to the donor and acceptor fragments (Figure 2a). The fluorescent coumarin and benzothiazole donors have the characteristic absorption signal with small peaks around 310 nm in compounds 1a and 2a, and 320 nm in compounds 1b and 2b respectively (Figure 2a and Table 1). The acceptor fragments based on Cy-7 dyes displayed large characteristic absorbance peaks around 770 nm. The acceptor absorbance peaks are 6–10 times larger than that of the donor fragments. The energy transfer dyes containing the coumarin donors (1a and 2a) have smaller absorbance peaks for both the donor and acceptor components compared to compounds 1b and 2b that contain the benzothiazole donors (see Figure 2a). This result indicates that the electronic interactions between the coumarin donor and the Cy-7 acceptor in the ground state might be stronger than that of benzothiazole donor and acceptor. Upon excitation of the donor absorption maximum at 306 nm, 307 nm, 318 nm and 315 nm in compounds 1a, 2a, 1b, 2b (1.0 μM, MeOH) respectively, the characteristic emission bands of the acceptor Cy-7 (around 780 nm) were observed (Figure 2b and Table 1). The undesirable fluorescence leakage from the donors with the characteristic emission in the range of 350–425 nm was also observed in the fluorescence spectra (Figure 2b). However, this leakage of fluorescence from the donors did not significantly decrease the energy transfer efficiency (ETE) from the donors to the acceptors in these four energy transfer systems. The parameter ETE is defined as:

Figure 2.

a) Absorption spectra of equimolar (1.0 μM) 1a–b, 2a–b in MeOH. b) Fluorescence spectra of equimolar (1.0 μM) 1a–b, 2a–b excited at 306, 318, 307 and 315 nm respectively in MeOH. c) Fluorescence spectra of equimolar (1.0 μM) 1a–b, 2a–b and IR-775 excited at 306, 318, 307, 315 and 315 nm respectively in MeOH.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of dyes 1a–b and 2a–b and acceptor IR-775 in methanol.

| Compds | Absorption | Emission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λabs[nm](a) | logεmax | λabs[nm](b) | logεmax | λem[nm](c) | ETE%(c) (%)(d) | FEF(e) | φ(f) | Δλ(g) | |

| 1a | 306 | 4.00 | 767 | 5.08 | 782 | 99 | 6.9 | 0.01 | 476 |

| 1b | 318 | 4.38 | 769 | 5.28 | 780 | 98 | 19.2 | 0.01 | 462 |

| 2a | 307 | 3.96 | 775 | 5.10 | 786 | 94 | 6.3 | 0.01 | 479 |

| 2b | 315 | 4.28 | 775 | 5.26 | 786 | 94 | 17.0 | 0.01 | 471 |

| IR-775 | - | - | 775 | 5.20 | 790 | - | 1.0 | - | - |

Maximal absorption of donor.

Maximal absorption of acceptor.

Maximal emission of the cassettes.

Energy transfer efficiencies.

Fluorescence enhancement factors relative to the acceptor.

Quantum yields, 7-hydroxycoumarin is used as the standard (φ = 0.35, MeOH), which is calculated using tryptophan (φ =0.14, MeOH).

Psuedo-Stokes shifts of the cassette.

The overall ETE for UPSS 1a–b and 2a–b dyes were very efficient (94%–99%). This indicates that almost all irradiation energy received by the donors was transferred to the acceptors. The sharp peaks around 625 nm are due to the double excitation phenomenon, which has been removed from the spectra for better presentation of the data (Figure 2b). It was also observed small fluorescence shoulders around 700 nm to the left of the major emission peak of every compound, which might be corresponding to minor π*- π transition in the π –conjugated Cy-7 systems.

The photophysical data of the UPSS 1a–b, 2a–b and acceptor IR-775 are given in Table 1. All four energy transfer dyes prepared have very large pseudo-Stokes shifts in the range of 462–479 nm. To the best of our knowledge, these are the largest pseudo-Stokes shifts energy transfer dyes that have ever been reported, and they are much larger than those of any donor-acceptor energy transfer systems reported in the literature. Through-bond energy transfer cassettes have pseudo Stokes shifts < 230 nm15–17 and those of the typical fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based systems are limited within 100 nm.18 In order to employ an energy-transfer compound for practical applications, the fluorescence intensity of the acceptor in the donor-acceptor system must be greater than that of the acceptor (without the donor) when it is excited at the donor absorption wavelength. For comparison, the fluorescence spectra were examined of an equimolar mixture (1.0 μM) of IR-775, which has a similar fluorescence wavelength as the acceptors, and the UPSS dyes (Figure 2c). As is evident from Figure 2c, the fluorescence enhancement factors (FEFs) are 6.9-, 6.3-, 19.2-, and 17.0-fold for the compounds 1a, 2a, 1b and 2b respectively. FEFs of compounds 1b and 2b are almost three times larger than that of fluorophores 1a and 2a because the former two compounds can absorb three times more light than the last two compounds (Figure 2a). The FEFs of compounds 1b and 2b are much longer than those of other typical FRET-based or through-bond energy transfer systems (~ 6.0-fold).

For sulfonated UPSS dyes 2a and 2b, their spectral properties were also determined under aqueous environments. Because they formed aggregates in pure PBS, a mix solvent (50% PBS 7.4, 50% MeOH) was used. The spectral behaviors of these two compounds in the mix solvent environment are very similar to that in organic methanol solvent. Two characteristic absorbance bands were observed for each compound, which were corresponding to the donor and acceptor absorbance peaking around 310 nm and 770 nm respectively (Figure S1a and table S1). Excited at 310 nm, emission maximum was detected at 790 nm (Figure S1b and table S1). The ETE for 2a is moderate (37%), indicated by a big fluorescence emission peak from the donor at 470 nm, which is a bathochromic shift compared to the spectra in methanol (Figure S1b and Figure 2b). Interestingly, UPSS 2b was three time brighter in aqueous media than in methanol (quantum yield is 0.03 and 0.01 respectively). The ETE of 2b is 95% in aqueous solution similar to that in methanol. In addition, both 2a and 2b have excellent FEFs, 6.2 and 19.2, respectively.

In conclusion, we have developed a platform for the facile synthesis of UPSS dyes based on energy transfer. The acceptor in the platform was Cy-7 dyes, which emit maximally around 785 nm. Various donor molecules containing a hydroxyl group were activated under basic condition and then conjugated with the acceptor. Fluorescent 7-hydroxyl coumarin a-OH and benzothiazole b-OH are the donors that were coupled with IR-775 and IR-783 to give four UPSS dyes, 1a–b and 2a–b. Excellent photophysical properties of these four novel UPSS dyes were determined both in methanol. The key feature is their very large pseudo-Stokes shifts (462 to 481 nm), which could be the largest ones among all published energy transfer dyes. This special feature of the UPSS dyes could also lead to novel light-harvesting materials. Moreover, the energy transfer efficiency of these four UPSS dyes from the donors to the acceptors is very high, which is >94%. This implies that most of the irradiation energy put on the donor was relayed to the acceptors. Also these UPSS dyes have excellent FEFs > 6. FEFs of compounds 1b and 2b are even up to 19 folds. These advantageous FEF properties of UPSS dyes are expected to be favorable for various imaging applications under physiological conditions. To make the current four UPSS dyes more useful, reactive functional groups will be introduced for further conjugation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NMR facility at University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center for acquiring the NMR data. This research was supported in part by NIH CA135312 and GM 094880.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: detailed experimental procedures, quantum yield calculation, synthesis and characterization data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Kobayashi H, Ogawa M, Alford R, Choyke PL, Urano Y. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2620–2640. doi: 10.1021/cr900263j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han J, Burgess K. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2709–28. doi: 10.1021/cr900249z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goncalves MST. Chem Rev. 2009;109:190–212. doi: 10.1021/cr0783840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pham W, Cassell L, Gillman A, Koktysh D, Gore JC. Chem Commun. 2008:1895–1897. doi: 10.1039/b719028j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vendrell M, Samanta A, Yun S-W, Chang Y-T. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4760–4762. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05519d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masotti A, Vicennati P, Boschi F, Calderan L, Sbarbati A, Ortaggi G. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:983–987. doi: 10.1021/bc700356f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng XJ, Song FL, Lu E, Wang YN, Zhou W, Fan JL, Gao YL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4170–4171. doi: 10.1021/ja043413z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myochin T, Kiyose K, Hanaoka K, Kojima H, Terai T, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3401–3409. doi: 10.1021/ja1063058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samanta A, Vendrell M, Das R, Chang Y-T. Chem Commun. 2010;46:7406–7408. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02366c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueno Y, Jose J, Loudet A, Perez-Bolivar C, Anzenbacher P, Jr, Burgess K. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:51–55. doi: 10.1021/ja107193j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheriya RT, Joy J, Alex AP, Shaji A, Hariharan M. J Phy Chem C. 2012;116:12489–12498. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loudet A, Thivierge C, Burgess K. Dojin News. 2011;137:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi J, Han M-S, Chang Y-C, Tung C-H. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:1758–1762. doi: 10.1021/bc200282t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.General procedure for the synthesis of energy transfer dyes 1a–b: To a solution of donor phenol (3.0 eq) in anhydrous DMF was added NaH (4.5 eq). Hydrogen bubbling was seen immediately, and sonication was used to help dissolve the compound in DMF. After stirring at r.t. for 30 min, IR-775 (1.0 eq) was added and the solution was stirred overnight. An ice-cold HCl solution (1 M) was added into the DMF solution, and the product was precipitated out of the solution. The collected crude product was purified by flash column eluting with MeOH:CH2Cl2 (10:1) to yield the desired product as a blue solid.Compound 1a: dark blue solid (38% yield); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) λ 7.79 (d, J = 14.4.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.72 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.37–7.34 (m, 2 H), 7.24 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.08 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.31 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.17 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1 H), 3.67 (s, 6 H), 2.78 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 4 H), 2.06 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.34 (s, 12 H). HRMS calculated for [M]+ C41H41N2O3+, 609.3112, found 609.3133.Compound 1b: dark blue solid (77% yield); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) λ 8.68 (s, 1 H), 7.90–7.87 (m, 3 H), 7.84 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.38 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.09 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.19 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 3.69 (s, 6 H), 2.79 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 4 H), 2.06 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.37 (s, 12 H); HRMS calculated for [M ]+ C48H47N6O2S+, 771.3476, found 771.3488.General procedure for the synthesis of energy transfer dyes 2a–b: To a solution of donor phenol (3.0 eq) in anhydrous DMF was added NaH (4.5 eq). Hydrogen bubbling was seen immediately, and sonication was used to help dissolve the compound in DMF. After stirring at r.t. for 30 min, IR-783 (1.0 eq) was added and the solution was stirred overnight. The solvent DMF was removed under reduced pressure, and the product was purified by reverse phase C18 semi-Prep HPLC (Method: Solvent A: H2O and solvent B CH3CN, gradient 10–90 % of solvent B in 20 min).Compound 2a: dark blue solid (46% yield); (1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) λ 7.92 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.91 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.38–7.35 (m, 4 H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 8.17 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.21–7.19 (m, 3 H), 7.21–7.19 (m, 3 H), 7.14 (s, 1 H), 6.31 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.25 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 2 H), 4.16 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.80 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.07 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.98–1.90 (m, 8 H), 1.35 (s, 12 H). HRMS calculated for [M]− C47H51N2O9S2−, 851.3041, found 851.3067.Compound 2b: dark blue solid (25% yield); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) λ 9.05 (s, 1 H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.97 (bs, 2 H), 7.87 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.58 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.38–7.35 (m, 4 H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H),7.19 (bs, 2 H), 7.14 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.16 (bs, 4 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 2.88 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.79 (bs, 4 H), 2.07 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.00–1.90 (m, 8 H), 1.39 (s, 12 H). HRMS calculated for [M]− C54H57N6O8S3−, 1013.3405, found 1013.3402.

- 15.Lin W, Yuan L, Cao Z, Feng Y, Song J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:375–379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J, Gonzalez O, Aguilar-Aguilar A, Pena-Cabrera E, Burgess K. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:34–36. doi: 10.1039/b818390b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao GS, Thoresen LH, Burgess K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14668–14669. doi: 10.1021/ja037193l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.