Abstract

Background

Haemophilus influenzae is an important human commensal pathogen associated with significant levels of disease. High-throughput DNA sequencing was used to investigate differences in genome content within this species.

Results

Genomic DNA sequence was obtained from 85 strains of H. influenzae and from other related species, selected based on geographical site of isolation, disease association and documented genotypic and phenotypic differences. When compared by Mauve alignment these indicated groupings of H. influenzae that were consistent with previously published analyses; capsule expressing strains fell into two distinct groups and those of serotype b (Hib) were found in two closely positioned lineages. For 18 Hib strains representing both lineages we found many discrete regions (up to 40% of the total genome) displaying sequence variation when compared to a common reference strain. Evidence that this naturally occurring pattern of inter-strain variation in H. influenzae can be mediated by transformation was obtained through sequencing DNA obtained from a pool of 200 independent transformants of a recipient (strain Rd) using donor DNA from a heterologous Hib strain (Eagan).

Conclusion

Much of the inter-strain variation in genome sequence in H. influenzae is likely the result of inter-strain exchanges of DNA, most plausibly through transformation.

Keywords: Haemophilus influenzae, Genome sequence, Population structure, Transformation

Background

Haemophilus influenzae is a frequently isolated member of the commensal microbiota of the human nasopharynx that also causes a variety of diseases including invasive infections (meningitis and septicaemia) as well as diseases resulting from contiguous spread within the respiratory tract, such as otitis media, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, epiglottitis, and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An important question is the extent to which genotypic variation within the species, especially that which affects surface expressed structures such as capsule, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and outer membrane proteins (OMPs), influences pathogenesis.

Within naturally occurring populations of transformable bacteria, it has been proposed that each strain in a population contributes to and can acquire genes from the pan-genome (the superset of all genes of the species) [1-3]. This hypothesis suggests that genetic exchange, especially through transformation-mediated homologous recombination, plays a major role in shaping the diversity of H. influenzae, and that these variations affect commensal and virulence behaviour. If so, investigations that detail the extent of the genomic diversity of the species and the mechanisms by which this diversity is transferred between strains are important for understanding both the population dynamics and characterising the genetic basis of the differences in severity and spectrum of disease associated with particular strains.

H. influenzae was the first free-living organism to have its genome sequenced [4]. This breakthrough marked the beginning of the “genome age” and offered the potential to gain more detailed information on the population structure of the species than current methods, including multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [5-13]. However, the availability of complete genome sequences for only a few strains is insufficient to interrogate the extent of the genetic diversity of H. influenzae and its close species relatives. In this study, a detailed analysis of 18 H. influenzae type b (Hib) strains compared to a common reference identified regions of high SNP density or sequence mismatches consistent with inter-strain exchange of DNA most plausibly derived from other H. influenzae strains through transformation, rather than phage or conjugative transfer. Further evidence for the role of transformation in the import of novel sequence flanked by regions of DNA found in both the donor and recipient was obtained through sequencing DNA obtained from a pool of strains each transformed with DNA from a heterologous donor Hib strain.

Results

Whole genome sequencing of 85 strains of Haemophilus spp

The genomes of 96 strains of Haemophilus spp. (Table 1) were sequenced using the Illumina GAII platform. For 85 of these strains where sufficient coverage had been attained, genome sequences of between 1.27 Mbp to 1.91 Mbp in length were assembled by Velvet [14] (Table 1). The sequencing and assembly resulted in between 351 and 1521 contigs per strain with a median of 785 contigs per assembled genome. The genome sequences were partial and the %G+C content of these (37.94 to 40.39%) was higher than expected based on data from other completed H. influenzae genomes (38.01-38.15%). DNA similarity searches and mapping of the sequence reads using MAQ [15] confirmed that the higher %G+C regions of the genomes had been preferentially sequenced, a known issue with early versions of the Illumina sequencing chemistry. We estimated the average genome coverage to be 83%, based on comparison with extant complete H. influenzae genome sequences; this data represents a ten-fold increase in the amount of genome sequence information available for H. influenzae.

Table 1.

Haemophilus strains selected for study

| Strain name | Type | Geographic location | Year | Length of sequence (Mb) | Disease/ Site of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM7190 |

a |

Malaysia |

1973 |

1.5 |

meningitis |

| RM6062 |

a |

England |

1965 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx |

| RM6064 |

a |

England |

1966 |

1.5 |

pleural fluid |

| RM6073 |

a |

England |

1966 |

1.6 |

bronchitis |

| RM7017 |

b |

Ghana |

1983 |

1.6 |

CSF |

| RM7060 |

b |

New York, USA |

1971 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx |

| RM7414 |

b |

Kenya |

1980’s |

1.5 |

|

| RM7419 |

b |

Kenya |

1980’s |

1.5 |

|

| RM7651 |

b |

Norway |

1976 |

1.7 |

|

| DC11238 |

b |

UK |

2003 |

1.8 |

meningitis |

| DC800 |

b |

UK |

1989 |

1.9 |

meningitis |

| DC8708 |

b |

UK |

2000 |

1.8 |

|

| DCG1574 |

b |

Gambia |

1993 |

1.8 |

nasopharynx |

| Eagan |

b |

|

|

1.5 |

|

| RM7578 |

b |

Switzerland |

1983 |

1.8 |

|

| RM7582 |

b |

RSA |

1980’s |

1.8 |

|

| RM7598 |

b |

USA |

1985 |

1.8 |

|

| RM7018 |

b* |

Ghana |

1983 |

1.4 |

CSF |

| RM7122 |

b* |

Australia |

<1984 |

1.5 |

meningitis |

| RM7459 |

b* |

Iceland |

1984 |

1.4 |

CSF |

| RM7465 |

b* |

Iceland |

1985 |

1.6 |

CSF |

| RM7617 |

b* |

Malaysia |

1970’s |

1.5 |

CSF |

| RM6132 |

c |

England |

1964 |

1.6 |

chronic sinusitis |

| RM6134 |

c |

England |

1975 |

1.4 |

abscess |

| RM7422 |

c |

Kenya |

1986 |

1.4 |

|

| RM6158 |

e |

England |

1962 |

1.7 |

cystic fibrosis |

| RM6237 |

f |

England |

1963 |

1.4 |

nasal discharge |

| RM7283 |

f |

Malaysia |

1972 |

1.5 |

trachea |

| RM7290 |

f |

Malaysia |

1974 |

1.5 |

trachea(malnutrition) |

| PLMIOG2822H-L |

H. haemolyticus |

|

|

1.6 |

|

| PLh.hlnctc10659T |

H. haemolyticus |

|

|

1.6 |

|

| PLHparaphorH-L |

H. paraphrophilus |

|

|

1.7 |

|

| PLMIOG2838H-L |

H. haemolyticus |

|

|

1.4 |

|

| DCMO-099-5-LST-8 |

H. parainfluenzae |

UK |

1997 |

1.7 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCMO-099-8-MST-8 |

H. parainfluenzae |

UK |

1997 |

1.6 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCO-CFE24-1-T2ST-27 |

H. parainfluenzae |

UK |

2001 |

1.8 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCO-OM30-1-A1 |

H. parainfluenzae |

UK |

2001 |

1.6 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT2T1ST-34 |

H. parainfluenzae |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.9 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT5A1ST-41 |

H. parainfluenzae |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.9 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT7B2ST-47 |

H. parainfluenzae |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.8 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT8A1ST-52 |

H. parainfluenzae |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.9 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| RY15 |

H. parainfluenzae |

|

|

1.7 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| RY20 |

H. parainfluenzae |

|

|

1.7 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| RY22 |

H. parainfluenzae |

|

|

1.9 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| RY8 |

H. parainfluenzae |

|

|

1.7 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT2B3ST-33 |

hybrid |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.4 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCG-T53T1 |

hybrid |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DCT8B3ST-51 |

hybrid |

Gambia |

2001 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx (commensal) |

| DH1500spain |

NTHi |

Spain |

2000 |

1.4 |

COPD |

| DH1559spain |

NTHi |

Spain |

2000 |

1.5 |

COPD |

| DH1630spain |

NTHi |

Spain |

2000 |

1.3 |

COPD |

| DH398spain |

NTHi |

Spain |

2000 |

1.5 |

COPD |

| Fi176 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.5 |

otitis media |

| Fi723 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.6 |

otitis media |

| Fi981 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.7 |

otitis media |

| RM6011 |

NTHi |

UK |

1984 |

1.3 |

meningitis |

| RM6019 |

NTHi |

UK |

1984 |

1.3 |

meningitis |

| RM6033 |

NTHi |

UK |

1984 |

1.5 |

pus hydrosalpinx |

| RM6051 |

NTHi |

UK |

1985 |

1.5 |

CSF |

| RM7028 |

NTHi |

PNG |

1980’s |

1.5 |

blood |

| RM7308 |

NTHi |

South Korea |

1984 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx |

| RM7309 |

NTHi |

South Korea |

1984 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx |

| RM7347 |

NTHi |

USA |

1985 |

1.4 |

sputum |

| RM7448 |

NTHi |

Iceland |

1978 |

1.4 |

blood |

| RM7477 |

NTHi |

Iceland |

1986 |

1.6 |

|

| RM7490 |

NTHi |

RSA |

1980’s |

1.6 |

CSF |

| DH1513spain |

NTHi |

Spain |

2000 |

1.5 |

COPD |

| Fi1180 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.6 |

otitis media |

| Fi162 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.7 |

otitis media |

| Fi667 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

1.7 |

otitis media |

| RM7029 |

NTHi |

PNG |

1980’s |

1.6 |

blood |

| RM7637 |

NTHi |

China |

1971 |

1.4 |

sputum |

| DC7331 |

NTHi |

UK |

1997 |

1.8 |

meningitis |

| DC7654 |

NTHi |

UK |

1997 |

1.8 |

blood |

| DC7695 |

NTHi |

UK |

1997 |

1.9 |

CSF |

| DCg2120 |

NTHi |

Gambia |

|

1.8 |

nasopharynx |

| DCH3151 |

NTHi |

Gambia |

1993 |

1.8 |

pneumonia |

| DCO-OM33-2B3ST-21 |

NTHi |

UK |

2001 |

1.5 |

nasopharynx |

| PLMIOG2819 |

|

|

|

1.5 |

|

| PLMIOG2820 |

|

|

|

1.5 |

|

| RM6006 |

|

|

|

1.4 |

|

| PLMIOG2836 |

|

|

|

1.7 |

|

| DCMO-009-14-S-TR-ST-12 |

|

UK |

1998 |

1.6 |

nasopharynx |

| PL10839T |

|

|

|

1.6 |

|

| PLMIOG2837 |

|

|

|

1.6 |

|

| RM7054 |

NTHi |

USA |

1984 |

|

blood (sepsis) |

| Fi1247 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| Fi1124 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| Fi486 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| Fi432 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| RM7068 |

NTHi |

PNG |

|

|

pneumonia |

| Fi285 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| PP H.parasuis |

NTHi |

|

|

|

|

| RM7876 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fi1200 |

NTHi |

Finland |

1995 |

|

otitis media |

| RM7066 |

The 96 strains selected for genome sequencing are listed along with respective information on serotype, isolation, and associated disease. The total length of the genome sequence following assembly is listed (to the nearest 0.1 Mbp) for each strain. The 11 strains below the horizontal line are those for which the quality of the assembled genome sequence was insufficient for the sequence data to be included in subsequent analyses.

* Strains were originally designated as NT.

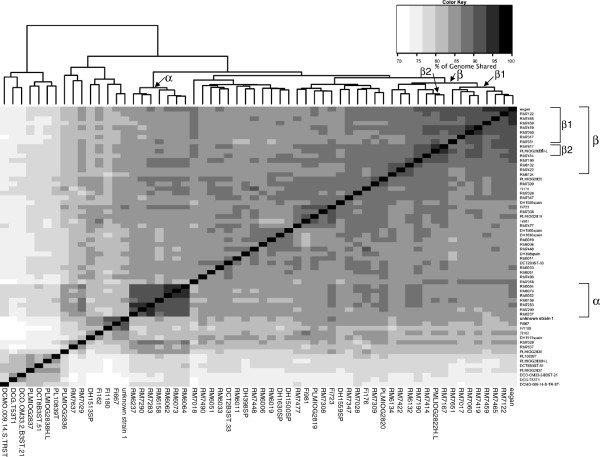

The genome assemblies were aligned in a pair-wise fashion using Mauve [16]. The length of the aligned portion of genomes achieved between any pair of strains, expressed as a percentage of the genome sequence length, was used as a measure of the relatedness of the strains. These pair-wise relationships were displayed as a heatmap using the R statistical package included within the analysis software (Figure 1). This method of ordering of strains is dependent on each having a similar degree of sequence coverage, and hence assembly length, thus the analysis was confined to data for the 60 genomes of H. influenzae and H. haemolyticus sequenced in the same flow cell (see Methods). A tree obtained following a simpler SNP-based analysis of the genome sequences (Additional file 1: Figure S1) gave an overall similar grouping of strains, validating the output from the Mauve analysis.

Figure 1.

Whole genome heat map, constructed by Mauve, to achieve pairwise percentage of genome sequence alignment. Pair-wise Mauve alignments were conducted with 60 H. influenzae and H. haemolyticus genome sequences from strains included on a single sequencing flow cell. For each pair-wise comparison the length of the alignment achieved, expressed as the percentage of the total sequence length, was calculated and a distance matrix created. The heat map was created using the R statistical package and shows the clustered genomes determined by the default R heatmap function clustering methods ( http://www.r-project.org/). At the top of the figure, an indication of the relatedness between genomes is given. Mauve achieved pairwise genome sequence alignments of between 69.8 and 94.4% across our range of genomes. Strains are listed in the same order on the x and y axes; groupings discussed in the text are indicated along the top axis and the relevant strains are indicated by brackets on the right hand side axis, labelled with a Greek letter.

Whole genome alignment reveals details of the genetic relationships of H. influenzae type b strains

Although this approach cannot give information on detailed phylogenetic relationships, it did allow the identification of some major groups and many sub-groups of strains (Figure 1) that were plausible and consistent with previously published analyses. Strains expressing a capsule fell into two groups (α and β in Figure 1) distinct from other H. influenzae strains. Hib strains were found only in two closely positioned sub-groups (β1 and β2 in Figure 1) which, interestingly, also included four strains that had originally been designated as non-typeable by serological tests (Table 1). BLAST analysis of these four genome sequences revealed a type b capsule locus in each case and all four strains were recorded as being isolated from CSF, or were associated with meningitis. We suppose that loss, or reduction, of type b capsule expression in these strains may have occurred during isolation and/or culture in the laboratory.

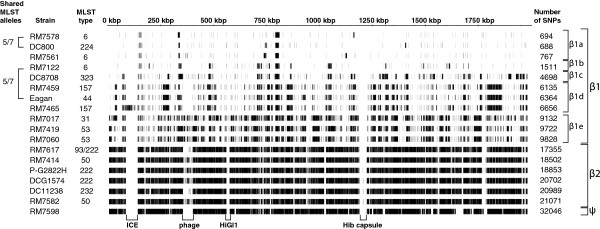

Based on the output from Mauve analysis, we selected Hib strains to analyse, in more depth, the differences in genome content that shape this level of diversity within the species. We used read-mapping by MAQ to investigate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between 18 Hib strains included in our genome sequence database and a common reference (Table 1, Figure 2). Strain RM7018, originally designated non-typeable was excluded as it was not a member of this Hib group based on Mauve analysis (Figure 1). Conversely, we included strain PLMIOG2822H-L, a type b strain that had been wrongly classified as H. haemolyticus. Sequence reads were mapped onto a complete reference Hib genome sequence (strain 10810; Genbank FQ312006.1) and used to identify SNPs for all Hib strains. The Hib groupings observed (Figure 2) were essentially the same as those observed by Mauve analysis (Figure 1). Based on the location and number of SNPs, the β1 strains can be sub-grouped into β1a-β1e, and strain RM7598 contains sufficient differences to constitute a separate group (ψ) from the β2 strains (Figure 2). Genome sequence data provides greater resolution in characterising divergence of strains that share identical or similar MLST profiles. For example, when we compared the patterns of SNPs of the sub-grouped β1a-β1e strains to their respective MLSTs, we found that strains RM7578 and DC800 shared similar blocks of SNPs when compared to strain 10810, in a pattern indicative of a common vertical inheritance. Strains RM7578 and DC800 had differed by two MLST alleles (Figure 2). Strains RM7122 and Eagan also differed by two MLST alleles but differed by 4,853 SNPs in comparison to strain 10810.

Figure 2.

SNPs of H. influenzae type b strain sequences when compared with Hib strain 10810. The complete genome sequence of the Hib strain 10810 was used as a reference against which the sequence reads of each strain were mapped using MAQ. Each vertical black line represents the location of a SNP. The equivalent groupings to those identified in Figure 1 are labelled on the right hand side. Regions marked at the bottom of the figure represent genome segments which are present in the reference strain 10810 but that may not be found in all other strains. The brackets on the left hand side of the figure indicate the number of MLST alleles shared between the pairs of genomes indicated; the sequence type (ST) of each strain is indicated to the right of its name.

Distribution of SNPs in Hib strains indicates putative transformation events and evidence of loss and gain of genes between Hib strains

The SNPs in the genomes representative of the three lineages of Hib strains (β1, β2 and ψ) were compared in more detail to the Hib strain 10810 (a β1 strain) reference genome (Figure 2). With respect to the reference genome, β1 strains had between 688 and 9,828 SNPs and β2 strains had between 17,355 and 21,071 SNPs (Figure 2). In the β1 strains the number of SNP-dense regions was low, whereas there were many more SNPs in the β2 strains due to their greater phylogenetic difference from the reference. The single ψ strain had 32,828 SNPs (not shown in Figure 2). Although the β2 strains and the ψ strain had a broadly similar number of SNPs, they were clustered in patterns that were distinct between the groups, a finding consistent with regions of high SNP density likely representing distinct recombination events.

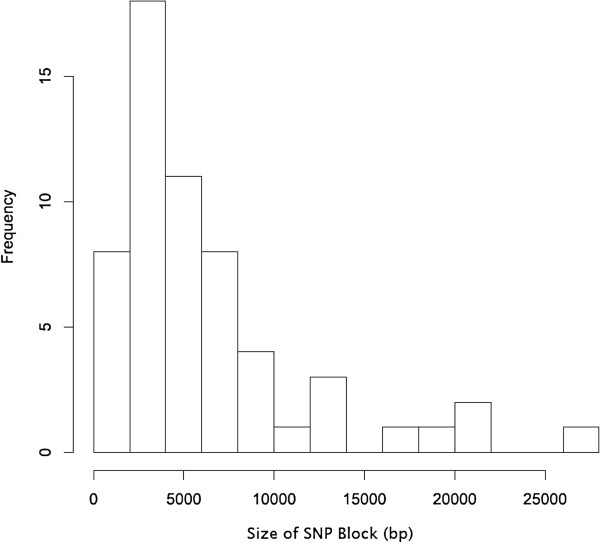

We hypothesised that “blocks” of DNA sequence with a high frequency of SNPs, separated by regions of the genome with low SNP density, could each represent an individual transformation event (Figure 2). To investigate this, we analysed two strains (RM7578 and RM7122) that have the same multi-locus sequence type. RM7578, the strain most closely related to the reference strain 10810, has five blocks of SNPs. For this analysis, blocks were defined as contiguous regions containing at least 30 SNPs, with each SNP separated by no more than 300 bp. 91% of 694 SNPs between strains RM7578 and 10810 were found within these five blocks, amounting in total to 23.5 kbp of DNA, or 1.2% of the genome. Strain RM7122 had 15 blocks of SNPs when compared to strain 10810, equivalent to 2.4% of the genome. In the β1 strains, the size of these blocks ranged from less than 0.5 to more than 25 kbp, with a median size of 4.8 kbp (Figure 3), findings within the range recently reported experimentally for H. influenzae strains [17]. We concluded that the blocks of SNPs identified between the closely related Hib strains represented recombination events, resulting in allelic exchanges that could delete or insert novel DNA, including whole genes.

Figure 3.

Size of SNP blocks found in the β1 group of Hib strains. This histogram represents the frequency of different sizes of SNP blocks (as defined in the text) in the genomes of β1 H. influenzae type b strains.

Inserted or deleted regions of DNA in Hib strains, relative to the genome sequence of reference strain 10810, were identified by BLASTN searches and the ACT genome browser. For a closely related strain, DC800, an example of insertion of a novel block of SNPs, mediated through transfer of DNA from an unknown donor, was identified. This inserted DNA included a putative gene flanked by regions of significant similarity. As a further example, comparison between two more divergent genomes (RM7060 and 10810) revealed at least 16 regions of DNA, each over 500 bp in length, that were present in one strain but not the other (Table 2). These regions constitute over 17.1 kbp or approximately 1% of the genome sequence length. Similarity searches using BLASTX revealed that eleven of the 16 regions contained sequences associated with phage proteins found in H. influenzae and related species. The remaining five regions encoded a putative tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase C, a predicted transcriptional regulator (NikR), a transport protein, and Hia and Hap proteins.

Table 2.

Regions in the H. influenzae strain RM7060 genome not found in strain 10810

| Accession number | Highest match by BLASTX analysis | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

ZP_01791522 |

NikR predicted transcriptional regulator |

H. influenzae PittAA |

|

AAL79955 |

Hia/YadA-like similar to neisserial GNA992 |

H. influenzae nontypeable strain 1860A |

|

AAM74927 |

Hap peptidase S6 |

H. influenzae HK274 |

|

ZP_05977792 |

putative carboxylate/amino acid/amine transporter |

Neisseria mucosa |

|

P46495 |

Putative integrase/recombinase HI_1572 |

H. influenzae |

|

ZP_00134779 |

Phage-related protein, tail component |

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

|

YP_001968298 |

Phage-related protein, tail component |

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

|

ZP_01791539 |

Mu-like prophage protein |

H. influenzae PittAA |

|

YP_003007008 |

Phage-related minor tail protein |

Aggregatibacter aphrophilus NJ8700 |

|

ZP_01791533 |

putative phage tail component |

H. influenzae PittAA |

|

YP_001290203.1 |

tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase C |

H. influenzae PittEE |

|

YP_001053216.1 |

predicted bacteriophage tail assembly protein |

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae L20 |

|

ZP_05990265 |

hypothetical protein COK_2151 |

Mannheimia haemolytica |

|

ZP_04753126 |

possible prophage antirepressor |

Actinobacillus minor NM305 |

|

ZP_04464399 |

Phage Mu protein F like protein |

H. influenzae 6P18H1 |

| YP_003007004 | phage protein | Aggregatibacter aphrophilus |

Experimental assessment of H. influenzae transformation

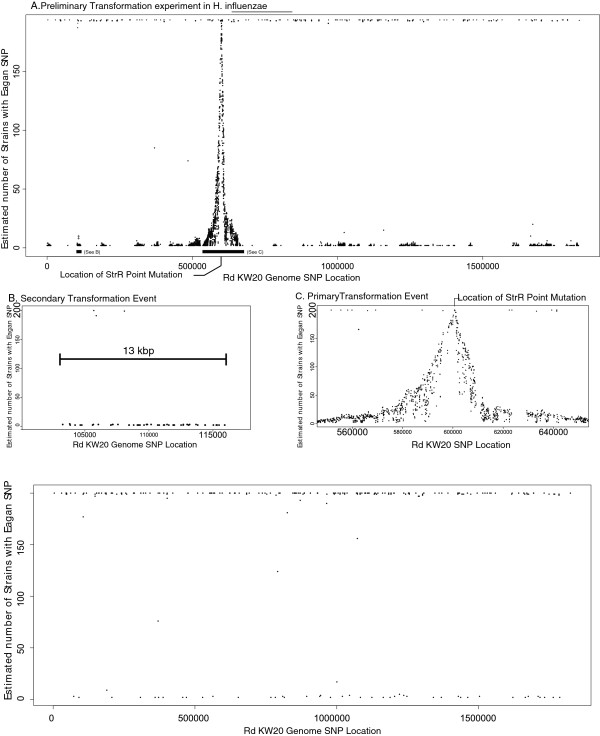

High throughput sequencing provides a useful experimental tool to examine in detail the recombination events associated with the transfer and exchange of DNA between H. influenzae strains through transformation. To this end, we investigated the transformation of DNA from a Hib strain donor into a high efficiency recipient strain. To ensure that each transformant was the result of a recombination event we used a spontaneous, high level streptomycin resistant (strR) derivative of strain Eagan (EaganstrR), possessing a point mutation in rpoB. Spontaneous strR mutants were infrequent (<10-10 in control transformations of Rd using streptomycin-sensitive Eagan DNA). Compared to strain Rd, the donor strain Eagan genome sequence had 18,789 SNPs relatively uniformly distributed throughout the genome (an average density of 10.3 SNPs per kbp) including the region around rpoB, the location of the strR mutation. Following transformation and selection on streptomycin, 200 independent Rd+EaganstrR colonies were pooled, the genomic DNA sequenced and mapped to the Rd reference genome sequence using the MAQ programme to identify SNPs. The number of Rd+EaganstrR transformants carrying each SNP was estimated from the pooled sequence using the SNPSeeker script [18] and is plotted in Figure 4. 4,501 SNPs consistent with transfer from Eagan (i.e. they were in the same genome location as the Eagan SNPs identified above) were found in the Rd+EaganstrR transformants. We identified 202 SNPs that were common to all respective sequence reads, were not linked closely to other SNPs and were found in both Rd+EaganstrR and Rd+Eagan transformants obtained in control experiments using non-strR Eagan DNA as donor. We conclude that these SNPs were consistent with, and most likely explained by, errors within the reported Rd genome sequence published in 1995. Another possibility, not mutually exclusive with sequencing errors, could be sequence drift in our laboratory strain (RM118) when compared to the sequenced isolate (Rd KW20). This level of error is similar to the several hundred SNPs reported upon re-sequencing of strain Rd by other investigators [17] and comparable with the 243 discrepancies found between the original 1997 E. coli strain MG1655 genome sequence [19] and the 2006 re-sequencing [20] of the same strain.

Figure 4.

Frequency of EaganstrRand Eagan SNPs in the Rd+EaganstrRand Rd+Eagan transformants. Panel A; Location and frequency of EaganstrR specific SNPs plotted as estimated number of strains (y-axis) against location in RdKW20 genome sequence (x-axis) using SNPSeeker. MAQ was used to identify SNPs in the pooled sequences from 200 transformants. The location of the strR point mutation is indicated. Panel B; A magnified view of one region marked on Panel A showing a putative secondary transformation event. The extent of the chromosomal region involved with this predicted transformation event (13 kbp) is marked. Panel C; A magnified view of the primary transformation event from Panel A with the location of the strR point mutation marked. Panel D; The location and frequency of Eagan-specific SNPs in the genome of pooled Rd+Eagan transformants (200); Eagan unmarked (wild-type) genomic DNA was used as the donor.

In the Rd+EaganstrR transformants, a large peak in SNP density centred on the site of the point mutation in rpoB conferring strR (Figure 4). Moving outwards from this central SNP peak, the Eagan-specific SNPs decrease at a relatively constant rate such that within 10 kbp of the strR mutation the frequency of strains containing Eagan-specific SNPs decreases at approximately 1 strain/100 bp. Across the 200 transformants, the region of the genome involved in recombination events centred on the strR locus would appear to span an arc of the genome over 80 kbp in size (Figure 4). Given that the strR locus can be at any location in the recombined block of DNA, this indicates a maximum size for the recombined block of at least 40 kbp.

In addition to the intense peak centred on the strR conferring SNP, secondary small peaks of SNPs can be observed at other locations in the genome. These secondary peaks contain Eagan strain-specific SNPs at a frequency of approximately 0.5% (Figure 4), a finding consistent with the occurrence of secondary transformation events in individual strains. These data serve to emphasize the significant impact of transformation in promoting changes in genome sequence between strains through the frequent uptake and recombination of one or more fragments of chromosomal DNA.

Discussion

The sequencing of whole genomes from multiple strains provides a powerful means by which to examine the diversity within a bacterial species. We sequenced the genomes of 96 selected strains of H. influenzae and closely related Haemophilus spp. The approximately 25 times depth of coverage for the genomes provides a substantial increase in the existing sequence information that can expand our understanding of the gene content and organisation of H. influenzae. The potential role of horizontal transfer of DNA through transformation in shaping the diversity of H. influenzae is illustrated by our detailed analysis of SNPs in the genome sequences obtained for 18 H. influenzae type b (Hib) strains. Through pair-wise alignment of genome sequences, we identified regions of high SNP density (range between 3 to 40.5% of genome length), or sequence mismatches, that were consistent with inter-strain exchange of DNA. Further, in the six strains most closely related to the reference genome of strain 10810, we identified the beginnings and ends of these “blocks” that were up to 25 kbp in size with a median size of 4.8 kbp (approx. 1.5% and 0.3% of the entire genome respectively). Strains of identical MLST type display allelic variation, insertions and deletions that can include complete genes most plausibly derived from other H. influenzae strains through transformation. These variations may be associated with important biological differences since they can involve sequences within genes such as hap and hif that are determinants of microbial-host interaction.

In a recent publication (17), Mell and colleagues allude to the natural variation within H. influenzae but do not characterise it. Here we document both the details and pattern of such sequence variation in several Hib strains, variations that are consistent with recombination, most plausibly achieved through DNA transformation. To provide further independent evidence for the role of transformation, we analysed 200 laboratory transformants that were made using donor and recipient strains of known genotypes.

Each transformant contained clusters of donor-specific SNPs that represent recombinational events through transformation. The sizes of the respective chromosomal segments involved are evidently up to 40 kbp in some transformants, somewhat larger than those reported recently (8.1 ± 4.5 kbp) for other transformations carried out in H. influenzae[17]. Both the extent of the region of the chromosome involved in recombination events, and the possibility of secondary transformation events targeting other positions in the genome, provide good evidence indicating the potential for transformation to substantially impact on genome evolution in this bacterium. Our findings provide evidence that transformation-mediated homologous recombination plays a major role in shaping the diversity of natural H. influenzae populations and that individual strains contribute to and can acquire genes from the superset of all genes of the species [1-3] as has been shown also in other bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae[21]. The “pan genome” is a resource from which specific strains can draw to allow the effective trialling of new alleles and genes in different genome backgrounds and which, through natural selection, promote survival and adaptation of H. influenzae within its obligate host, humans. The significant genetic divergence of genomic sequence, documented here for type b strains, but doubtless characteristic of the species as a whole, can provide information about the biological differences between strains that may determine in part the variations in commensal and pathogenic behaviour of the species.

The availability of whole genome sequencing raises the question of how best to determine the relatedness of strains of bacteria, especially in species where there is known to be substantial recombination. For H. influenzae, the relationships between strains inferred by the number of shared genes and the sequence similarity in house-keeping genes yield different tree topologies [3], indicating that the assumptions which underlie these methods do not reconcile phylogenetic relationships. Transformation and other mechanisms of recombination in H. influenzae are strong forces which can distort the perceived phylogenetic relationships between strains based on sequence similarity. It is evident from the strains examined in detail in this study that despite the genetic variation identified, there is considerable conservation of the genome between most strains. However, there are genetic elements in H. influenzae genomes which mediate genetic variation at a rate greater than ‘natural’ transformation. Mobile genetic elements such as phage and integrative and conjugative elements (ICE) promote more rapid genome evolution in response to strong selection pressure, such as the use of antibiotics in the human host. The ICE in H. influenzae is responsible for significant spread of antibiotic resistance in the bacterium and is able to cross the barrier to other species, such as H. parainfluenzae[22], at a rate which is greater than that predicted to be achievable through transformation.

Conclusions

The pair-wise alignment of whole genomes, using Mauve, provided us a useful means to inform on relationships between strains that are influenced by frequent recombination. Our findings provide evidence that transformation-mediated homologous recombination plays a major role in shaping the diversity of natural H. influenzae populations and that individual strains contribute to and can acquire genes from the superset of all genes of the species.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

Strains were selected for genome sequencing (Table 1) from a collection of more than 1900 strains archived in Oxford. A majority of the strains has been characterised by one or more methods including MLST, MLEE, 16S rRNA sequencing, biotyping, and capsular type. Data on the association of strains with different diseases, dates and geographical sites of isolation were also available for many strains. 46 H. influenzae strains were selected for study that represented the diversity within a tree created from the concatenated sequence data from the entire MLST database ( http://haemophilus.mlst.net). A further 15 strains were selected based on existing MLEE and biotype data. Finally, clinical, geographical and temporal data were used to identify some further strains that were included, based on criteria other than MLST or MLEE, as well as a number of strains from closely related species and sub-species of H. influenzae including H. haemolyticus, Haemophilus parahaemolyticus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Haemophilus paraphrophilus, H. influenzae biotype IV strains, and putative ‘hybrid’ H. influenzae-H. parainfluenzae strains (Table 1). The latter ‘hybrid’ strains are H. influenzae isolates that do not contain a fucK MLST allele, a characteristic of H. parainfluenzae, and therefore their classification is uncertain (personal communication Abdel Elamin, University of Oxford). Most of the serotype b strains were recovered from patients with invasive disease but a number were associated with non-symptomatic carriage.

Bacterial isolates were cultured from frozen on solid brain heart infusion (BHI) medium supplemented with 10% Levinthals reagent and 1% agar, and incubated at 37°C. For DNA preparation, bacteria were cultured on BHI liquid supplemented with haemin (10 μg/ml) and NAD (2 μg/ml).

Genome sequencing, assembly, and comparison of genome sequence data

Strains were grown on BHI broth and chromosomal DNA was isolated from bacteria using Qiagen columns as described by the supplier. The genomic DNA from 96 strains was sequenced using multiplex (12 separately indexed DNAs per lane) Illumina sequencing as described previously [21]. The sequencing was conducted utilising 7 lanes (84 DNAs) on one flow cell and one lane (12 DNAs) on a second flow cell. The 55 bp reads from each of the 96 strains were separated using the index tags, and then assembled using the Velvet assembly programme [14]. Genome sequences for eleven strains were rejected due to poor assembly; the result of insufficient coverage or large numbers of small contigs (lower part of Table 1). For 85 Haemophilus strains, genome sequences of between 1.27 Mbp to 1.91 Mbp in length were assembled by Velvet (Table 1).

The sequence reads were mapped to a reference using MAQ [15] and default parameters, these were then tested to identify the depth of reads covering the lower %G+C regions of DNA, as an indication of when coverage was insufficient for assembly.

A SNP-based tree was generated by mapping the Illumina fastq sequences against the reference sequence of Hib strain 101810 (acc. number FQ312006) using SMALT version 0.6.3 software, SNPs were called and a tree generated from the SNP alignment using FastTree.

Serotyping

The serotype of predicted type b strains was determined by the slide agglutination test using serotype-specific serum as described elsewhere [23]. The results from these tests were supported by BLAST analysis of the respective genome sequence derived in this study using published type b capsule gene sequence as a probe.

Transformation of H. influenzae

Genomic DNAs from strains Eagan and a spontaneous high level streptomycin resistant derivative, EaganstrR, were prepared and then used to transform strain Rd using the standard MIV protocol [24]. Transformants were selected following growth overnight on BHI plates with or without added streptomycin (500 μg/ml). 200 independent colonies were selected, pooled, and genomic DNA was isolated from the respective Rd+EaganstrR and Rd+Eagan transformants. The pooled genomic DNA from each transformation was sequenced on an individual Illumina GAII flow cell at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. The frequency of spontaneous strR mutation was calculated by plating on BHI/streptomycin plates competent Rd cells taken through the transformation procedure but without added donor DNA.

Abbreviations

Hib: Serotype b Haemophilus influenzae; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MLEE: Multi-locus enzyme electrophoresis; MLST: Multi-locus sequence typing; NTHi: Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PP, ERM and DWH designed the study and PP carried out the analyses of the whole genome sequence data thus obtained. SB and JP facilitated the sequencing of the bacterial genomes. PP, ERM and DWH were the main contributors to the writing of the manuscript, all authors read and approved the final draft.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Tree indicating the relatedness of Haemophilus genome sequences based on similarities in their patterns of SNPs. Illumina fastq sequences were mapped against the reference sequence of Hib strain 10810 and the tree was generated using FastTree from the SNP alignments. Some minor differences in strain placement when compared to Mauve analysis reflects those strains with the lowest quantity (and quality) of genome sequence information.

Contributor Information

Peter M Power, Email: peter.power@bfriars.ox.ac.uk.

Stephen D Bentley, Email: sdb@sanger.ac.uk.

Julian Parkhill, Email: parkhill@sanger.ac.uk.

E Richard Moxon, Email: richard.moxon@paediatrics.ox.ac.uk.

Derek W Hood, Email: derek.hood@ndm.ox.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

ERM and DWH were supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, UK and PP, SB and JP were supported by the Wellcome Trust. The authors are grateful for Thomas Connor at the Sanger Institute for help in producing the SNP-based tree.

References

- Boissy R, Ahmed A, Janto B, Earl J, Hall BG, Hogg JS, Pusch GD, Hiller LN, Powell E, Hayes J, Comparative supragenomic analyses among the pathogens Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae using a modification of the finite supragenome model. BMC Genomics. p. 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Medini D, Donati C, Tettelin H, Masignani V, Rappuoli R. The microbial pan-genome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(6):589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg J, Hu F, Janto B, Boissy R, Hayes J, Keefe R, Post J, Ehrlich G. Characterization and modeling of the Haemophilus influenzae core and supragenomes based on the complete genomic sequences of Rd and 12 clinical nontypeable strains. Genome Biol. 2007;8(6):R103. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, Bult CJ, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Merrick JM. et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269(5223):496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian M. A taxonomic study of the genus Haemophilus, with the proposal of a new species. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;93(1):9–62. doi: 10.1099/00221287-93-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser JM, Kroll JS, Moxon ER, Selander RK. Clonal population structure of encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1988;56(8):1837–1845. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1837-1845.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenkamp SJ, Munson RS, Granoff DM. Subtyping isolates of Haemophilus influenzae type b by outer-membrane protein profiles. J Infect Dis. 1981;143(5):668–676. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenkamp SJ, Munson RS, Granoff DM. Outer membrane protein and biotype analysis of pathogenic nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1982;36(2):535–540. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.535-540.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi CT, Alber D, Dull P, Mothershed EA, Whitney AM, Barnett GA, Popovic T, Mayer LW. High level of sequence diversity in the 16S rRNA genes of Haemophilus influenzae isolates is useful for molecular subtyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):3734–3742. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3734-3742.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos BG, Bernstein JM, Dryja DM, Murphy TF, Dickinson DP. Determination of the epidemiology and transmission of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae in children with otitis media by comparison of total genomic DNA restriction fingerprints. Infect Immun. 1989;57(9):2751–2757. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2751-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaves NI, Jordens JZ. Development of a ribotyping scheme forHaemophilus influenzae type b. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious. 1994;13(12):1038–1045. doi: 10.1007/BF02111824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet V, Huot H, Goldstein R. Molecular Genetic Basis of Ribotyping. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):262. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meats E, Feil E, Stringer S, Cody A, Goldstein R, Kroll J, Popovic T, Spratt B. Characterization of encapsulated and noncapsulated Haemophilus influenzae and determination of phylogenetic relationships by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(4):1623–1636. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1623-1636.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18(5):821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ruan J, Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008;18(11):1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14(7):1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mell JC, Shumilina S, Hall IM, Redfield RJ. Transformation of natural genetic variation into Haemophilus influenzae genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002151. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druley TE, Vallania FL, Wegner DJ, Varley KE, Knowles OL, Bonds JA, Robison SW, Doniger SW, Hamvas A, Cole FS. et al. Quantification of rare allelic variants from pooled genomic DNA. Nat Methods. 2009;6(4):263–265. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF. et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277(5331):1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Morooka N, Yamamoto Y, Fujita K, Isono K, Choi S, Ohtsubo E, Baba T, Wanner BL, Mori H. et al. Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia coli K-12 strains MG1655 and W3110. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006 0007. doi: 10.1038/msb4100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croucher NJ, Harris SR, Fraser C, Quail MA, Burton J, van der Linden M, McGee L, von Gottberg A, Song JH, Ko KS. et al. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science. 2011;331(6016):430–434. doi: 10.1126/science.1198545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M, van der Meer JR, Gaillard M, Harding RM, Hood DW, Crook DW. Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33(2):376–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram DL, Collier AM, Pendergrass E, King SH. Methods for serotyping nasopharyngeal isolates of Haemophilus influenzae: slide agglutination, Quellung reaction, countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis, latex agglutination, and antiserum agar. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9(5):570–574. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.5.570-574.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herriott RM, Meyer EM, Vogt M. Defined nongrowth media for stage II development of competence in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1970;101(2):517–524. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.2.517-524.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Tree indicating the relatedness of Haemophilus genome sequences based on similarities in their patterns of SNPs. Illumina fastq sequences were mapped against the reference sequence of Hib strain 10810 and the tree was generated using FastTree from the SNP alignments. Some minor differences in strain placement when compared to Mauve analysis reflects those strains with the lowest quantity (and quality) of genome sequence information.