Abstract

Background

A bacterial strain previously isolated from pyrite mine drainage and named BAS-10 was tentatively identified as Klebsiella oxytoca. Unlikely other enterobacteria, BAS-10 is able to grow on Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon and energy source, yielding acetic acid and CO2 coupled with Fe(III) reduction to Fe(II) and showing unusual physiological characteristics. In fact, under this growth condition, BAS-10 produces an exopolysaccharide (EPS) having a high rhamnose content and metal-binding properties, whose biotechnological applications were proven as very relevant.

Results

Further phylogenetic analysis, based on 16S rDNA sequence, definitively confirmed that BAS-10 belongs to K. oxytoca species. In order to rationalize the biochemical peculiarities of this unusual enterobacteriun, combined 2D-Differential Gel Electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) analysis and mass spectrometry procedures were used to investigate its proteomic changes: i) under aerobic or anaerobic cultivation with Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon source; ii) under anaerobic cultivations using Na(I)-citrate or Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon source. Combining data from these differential studies peculiar levels of outer membrane proteins, key regulatory factors of carbon and nitrogen metabolism and enzymes involved in TCA cycle and sugar biosynthesis or required for citrate fermentation and stress response during anaerobic growth on Fe(III)-citrate were revealed. The protein differential regulation seems to ensure efficient cell growth coupled with EPS production by adapting metabolic and biochemical processes in order to face iron toxicity and to optimize energy production.

Conclusion

Differential proteomics provided insights on the molecular mechanisms necessary for anaeorobic utilization of Fe(III)-citrate in a biotechnologically promising enterobacteriun, also revealing genes that can be targeted for the rational design of high-yielding EPS producer strains.

Background

Several species of enterobacteria use citrate as sole carbon and energy source. This capability is firstly due to appropriate transporters for citrate up-take, such as the citrate-specific proteins CitH and CitS [1,2] or like the tripartite tricarboxylate transporter (TTT) TctABC system able to transport several tricarboxylic acids into the bacterial cell [3] or like the ferric citrate transport system (the product of the fecABCDE operon) that shuttles the Fe(III)-citrate complex into the cytoplasm [4-7].

During aerobiosis, intracellular citrate is catabolized throughout the TCA cycle. Under anaerobic conditions, when TCA cycle is down-regulated, enterobacteria species, like Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella typhimurium, can grow on citrate by a Na(I)-dependent pathway, forming acetic acid and CO2 as final metabolites [1,8,9]. Genes specific for anaerobic citrate fermentation, such as those coding for regulators (citAB), catabolic enzymes (citCDEFG and oadGAB) and citrate transporters (citS and citW), have been identified in these bacteria [1,2,8,10]. The presence of sodium is essential for citrate symport by CitS and for the activity of oadGAB gene products that form the oxaloacetate decarboxylase complex. In fact, oxaloacetate decarboxylase converts oxaloacetate into pyruvate and pumps sodium externally to synthesize ATP [1,2,8,9].

Generally, iron is one of the major limiting nutrients [11] and citrate-fermenting enterobacteria do not usually thrive on high concentrations of Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon and energy source [12]. Indeed, there are habitats where the abundance of Fe(III) is so high, like in pyrite mine drainages, which represents one of the major elements to make rust-red the acidic waters. In this case, iron can represent an environmental hazard for life, especially for its oxidative properties and for the presence of other metals which increase the total toxicity of mine drainages and cause a significant reduction of microbial biodiversity [13-15]. Only specialized species can survive in extreme habitats with high heavy metal concentrations and carbon-depleted conditions and Enterobacteraceae are not expected to survive in such environments. Nevertheless, an enterobacterial strain was isolated under an iron mat formed by waters leached from pyrite mine drainages of Colline Metallifere, Tuscany, Italy [16]. This isolate, named BAS-10, was tentatively identified as K. oxytoca on the basis of partial (422 nt) 16S rDNA sequence and API Enterotube test [16]. Unique among Klebsiella strains, BAS-10 can ferment and proliferate on Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon and energy source, forming acetic acid and CO2 coupled with Fe(III) reduction to Fe(II) [12]. Under these growth conditions, BAS-10 produces an EPS made of rhamnose (57.1%), glucuronic acid (28.6%) and galactose (14.3%), which shows metal-binding properties [17,18]. Although extracellular EPS have been reported over recent decades and their composition, structure, biosynthesis and functional properties have been extensively studied, only a few have been industrially developed [19].

Chelating and sugar compositional properties of BAS-10 EPS are of high interest for potential biomedical, food, and environmental applications [18-20]. Further studies on BAS-10 physiology may be useful to develop efficient fermentation processes for EPS production. In order to investigate iron-dependent biochemical and metabolic adaptations and regulatory networks thereof during anaerobic growth on Fe(III)-citrate as the sole carbon source, a differential proteomic approach was used. In particular, proteomic repertoires from BAS-10 grown on Fe(III)-citrate under anaerobiosis, on Na-citrate under anaerobiosis and on Fe(III)-citrate under aerobiosis were comparatively evaluated.

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic identification

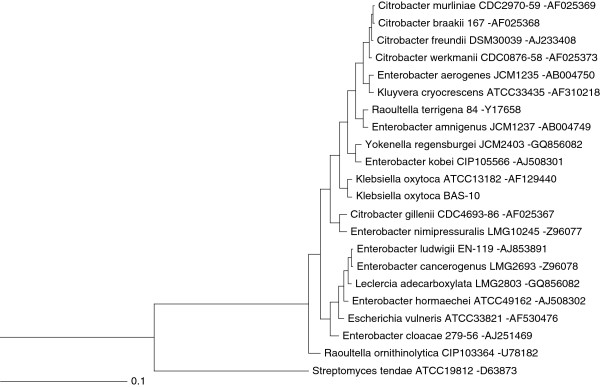

Physiological studies [12], EPS composition and metal-binding activity thereof [17,18] revealed characteristic peculiarities of BAS-10 strain. Thus, a sequence of 1447 nt gene was generated from BAS-10 16S rDNA (Additional File 1) to perform phylogenetic clustering. Two ClustalW analyses were performed by using the first twenty hits from Blast analysis, selecting only cultivable reference or whole strains from NCBI database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [21], respectively. Phylogenetic threes revealed that BAS-10 is related to K. oxytoca reference strain (Figure 1) and can be clustered into a group comprising other five very close related strains classified as K. oxytoca (Additional file 1 Figure S1). This investigation definitively confirmed previous taxonomical observations on BAS-10 [16].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of BAS-10 strain performed by using 16S rDNA sequences. The first twenty hits from BLAST analysis performed by selecting only cultivable reference strains were used to generate the phylogenetic three. The 16S rDNA sequence of Streptomyces tendae was used as outgroup. Distance unit is based on sequence identity. NCBI accession number of each 16S rDNA is reported after hyphen.

Proteomic analysis

To investigate iron-dependent cell processes and regulatory networks thereof associated to citrate fermentation and EPS production, BAS-10 was cultivated: i) under aerobic conditions on Fe(III)-citrate (FEC) as sole carbon source; ii) under anaerobic conditions using FEC or iii) Na(I)-citrate (NAC) as sole carbon source. Then, bacterial proteomes were analyzed using anaerobic FEC growth as pivotal condition. In particular, the “anaerobic FEC Vs aerobic FEC” differential analysis was carried out to reveal proteins that are required for anaerobic growth on FEC while “anaerobic FEC Vs anaerobic NAC” differential analysis was carried out to reveal proteins whose abundance is iron-dependent during anaerobic growth. In all cases, BAS-10 biomass samples were all harvested at late exponential growth phases, when anaerobic growth on FEC is coupled with iron-binding EPS production [12,16] at an average yield of 6.7 g/L (dry weight EPS per culture volume). Proteomic 2D-DIGE maps showed the occurrence of 869 reproducible protein spots (i. e. detected in all 2D-Gels) which were used to create the match set for comparative analysis. According to the criteria reported in the experimental section for identification of deregulated proteins, comparative analysis between FEC medium cultivations under anaerobic or aerobic conditions revealed 27 and 32 protein spots up- and down-regulated under anaerobic conditions, respectively (Table 1; Additional file 1 Figure S2). On the other hand, comparative analysis between cultivations in FEC and NAC media under anaerobic conditions revealed 28 and 42 protein spots as up- and down-regulated in the presence of Fe(III) (Table 1; Additional file 1 Figure S2). Among these protein spots, 46 resulted differentially abundant with a concordant profile in both analyses (anaerobic FEC vs aerobic FEC and anaerobic FEC vs anaerobic NAC) (Table 1), thus indicating that these proteins are specifically associated with anaerobic growth on FEC. The selected differentially abundant protein spots (83 in number) were alkylated, trypsinolyzed and identified by MALDI-TOF-peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) and nanoLC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS procedures (Table 1 and Additional file 1 Table S1). Corresponding protein entries were clustered into functional groups, according to KEGG (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/kegg2.html) [22], EcoCyc (http://ecocyc.org/) [23] and ExPASy (http://www.expasy.org) [24] databases (Additional file 1 Figure S3). Among the identified proteins, the most represented ones were related to central carbon metabolism -including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, citrate fermentation, pentose phosphate (PP) pathway -and membrane transport (Table 1; Additional file 1 Figure S3).

Table 1.

Functional classification and relative fold change of K. oxytoca BAS-10 proteins differentially expressed during anaerobic growth in FEC

| Spot | Protein name | Acronym | NCBI code | Theor. pI/Mr (kDa) | Exp. pI/Mr (kDa) | Functional classa | Relative fold changeb(−O2FEC Vs +O2FEC) | Relative fold changeb(−O2FEC Vs -O2NAC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase |

GLDH |

376386651 |

6.73/49 |

6.26/45 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

1 |

2.6 |

| 5* |

Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II 2 |

GlnK |

376394829 |

5.84/12 |

5.62/13 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

−3.2 |

−8.7 |

| 6 |

Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II 2 |

GlnK |

376394829 |

5.84/12 |

5.62/13 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

1 |

−2.7 |

| 7 |

Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II 2 |

GlnK |

376394829 |

5.84/12 |

5.20/13 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

1 |

−2.2 |

| 3* |

Ketol-acid reductoisomerase |

IlvC |

376396684 |

5.25/54 |

5.04/54 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

2.3 |

2.2 |

| 4 |

D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase |

PHGDH |

365906793 |

6.06/44 |

5.92/46 |

Amino Acid Metabolism |

1 |

−2.7 |

| 8 |

Major outer membrane lipoprotein 1 |

Lpp |

376401994 |

9.36/8 |

4.16/12 |

Cell wall |

1 |

3.4 |

| 9 |

Major outer membrane lipoprotein 1 |

Lpp |

376401995 |

9.36/9 |

4.04/12 |

Cell wall |

1 |

3.4 |

| 10 |

Major outer membrane lipoprotein 1 |

Lpp |

376401994 |

9.36/8 |

4.44/12 |

Cell wall |

1 |

1.7 |

| 37 |

Aerobic respiration control protein ArcA |

ARCA |

376394332 |

5.30/27 |

5.04/29 |

Central carbon metabolism |

1.9 |

1 |

| 19* |

Glucose-specific phosphotransferase enzyme IIA component |

EIIAGlc |

376399349 |

4.73/18 |

4.6/22 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−1.9 |

−1.7 |

| 20* |

Glucose-specific phosphotransferase enzyme IIA component |

EIIAGlc |

376399349 |

4.73/18 |

4.62/20 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−1.5 |

−1.4 |

| 17* |

Hypothetical protein HMPREF9694_04828 (dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase, E2 component) |

SucB |

376395176 |

5.74/44 |

5.39/54 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−2.8 |

−3.6 |

| 41 |

Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha |

A-SCS |

365909192 |

5.89/30 |

5.65/30 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−3.9 |

1 |

| 33 |

Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit beta |

B-SCS |

365909191 |

5.35/42 |

5.05/43 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−1.8 |

1 |

| 42 |

Fumarate hydratase class II |

FH |

376401593 |

6.02/50 |

5.92/46 |

Central carbon metabolism |

1 |

−2.7 |

| 2* |

Fumarate reductase flavoprotein subunit |

FrdA |

376396036 |

5.60/66 |

5.44/77 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.1 |

2.6 |

| 22* |

Malate dehydrogenase |

MDH |

376398117 |

5.57/33 |

5.34/34 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−3.1 |

−2.7 |

| 23* |

Malate dehydrogenase |

MDH |

376398117 |

5.57/33 |

5.08/29 |

Central carbon metabolism |

−1.9 |

−2.7 |

| 14 |

Citrate lyase beta subunit |

CitE |

376376734 |

5.33/31 |

4.87/29 |

Central carbon metabolism |

1.9 |

1 |

| 26 |

Citrate lyase beta subunit |

CitE |

376376734 |

5.33/31 |

5.07/31 |

Central carbon metabolism |

4.9 |

1 |

| 36* |

Citrate lyase beta subunit |

CitE |

376376734 |

5.33/31 |

5.19/29 |

Central carbon metabolism |

3.0 |

2.4 |

| 15* |

Citrate lyase, alpha subunit |

CitF |

365908401 |

5.94/55 |

5.98/55 |

Central carbon metabolism |

8.7 |

9.0 |

| 16* |

Citrate lyase, alpha subunit |

CitF |

365908401 |

5.94/55 |

5.89/55 |

Central carbon metabolism |

14.1 |

11 |

| 24* |

Oxaloacetate decarboxylase alpha chain |

OadA |

376376739 |

5.44/63 |

5.04/64 |

Central carbon metabolism |

10.4 |

8.7 |

| 25* |

Oxaloacetate decarboxylase alpha chain |

OadA |

376376739 |

5.44/63 |

4.7/43 |

Central carbon metabolism |

3.7 |

2.8 |

| 81* |

Oxaloacetate decarboxylase alpha chain |

OadA |

376376739 |

5.44/63 |

4.74/43 |

Central carbon metabolism |

4.0 |

2.4 |

| 29* |

Pyruvate formate lyase |

PFL |

376393708 |

5.63/85 |

5.09/80 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.7 |

12.4 |

| 30* |

Pyruvate formate lyase |

PFL |

376393708 |

5.63/85 |

5.3/80 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.1 |

15.4 |

| 31* |

Pyruvate formate lyase |

PFL |

376393708 |

5.63/85 |

5.37/80 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.9 |

12.1 |

| 32* |

Pyruvate formate lyase |

PFL |

376393708 |

5.63/85 |

5.44/77 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.7 |

12.4 |

| 35* |

Pyruvate formate lyase |

PFL |

376393708 |

5.63/85 |

5.16/43 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.3 |

3.4 |

| 27* |

Phosphotrans-acetylase |

PTA |

365911544 |

5.26/77 |

5.27/65 |

Central carbon metabolism |

3.6 |

2.7 |

| 12* |

Acetate kinase A/propionate kinase 2 |

ACK |

365911543 |

5.84/44 |

5.39/27 |

Central carbon metabolism |

4.1 |

1.7 |

| 46* |

Triosephosphate isomerase |

TIM |

376397984 |

5.82/26 |

5.5/26 |

Central carbon metabolism |

1.6 |

1.5 |

| 38* |

Pyruvate kinase |

PK |

365911037 |

6.00/52 |

5.78/55 |

Central carbon metabolism |

1.9 |

1.9 |

| 21* |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

GAPDH |

376401359 |

6.33/36 |

6.2/31 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.2 |

1.5 |

| 28 |

Pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit E1 |

PDH |

365908482 |

5.47/100 |

5.52/67 |

Central carbon metabolism |

2.4 |

1 |

| 40 |

3-Methyl-2-oxobutanoate hydroxymethyltransferase |

PanB |

365908516 |

5.64/28 |

5.34/29 |

Cofactor biosynthesis |

1 |

−2.5 |

| 49 |

6,7-Dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase |

RibH |

365908789 |

5.12/16 |

4.87/14 |

Cofactor biosynthesis |

1 |

−2 |

| 51 |

DNA protection during starvation protein |

DPS |

376393609 |

5.72/19 |

5.61/16 |

DNA ricombination, replication and repair |

−1.5 |

1 |

| 50 |

DNA-binding protein HU-alpha |

HU-2 |

376396790 |

9.40/9 |

9.07/11 |

DNA ricombination, replication and repair |

1 |

−2.3 |

| 52* |

ATP synthase subunit beta |

ATPβ |

376397178 |

4.93/50 |

4.81/51 |

Energy metabolism |

2.5 |

2.2 |

| 53* |

ABC transporter arginine-binding protein 1 |

ArtJ |

376393664 |

6.90/27 |

5.98/25 |

Membrane Transport |

4.9 |

7.4 |

| 57* |

Glutamate and aspartate transporter subunit |

DEBP |

365909131 |

8.61/33 |

7.85/30 |

Membrane Transport |

−7.7 |

−6.7 |

| 58* |

Glutamine-binding periplasmic protein |

GlnH |

376388520 |

8.74/27 |

5.81/26 |

Membrane Transport |

−1.9 |

−2.4 |

| 59* |

Glutamine-binding periplasmic protein |

GlnH |

376388520 |

8.74/27 |

7.8/25 |

Membrane Transport |

−3.1 |

−6.2 |

| 60* |

Glutamine-binding periplasmic protein |

GlnH |

376388520 |

8.74/27 |

6.87/25 |

Membrane Transport |

−2.3 |

−3.8 |

| 34* |

Leucine ABC transporter subunit substrate-binding protein LivK |

LivK |

365907255 |

5.71/40 |

5.03/42 |

Membrane Transport |

3.0 |

3.5 |

| 61* |

Maltose ABC transporter periplasmic protein |

MBP |

365907919 |

6.88/43 |

5.96/40 |

Membrane Transport |

−7 |

−14 |

| 56* |

D-galactose-binding periplasmic protein |

MGLB |

376381367 |

6.14/36 |

5.42/29 |

Membrane Transport |

−2.6 |

−2.5 |

| 13 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

4.98/31 |

Membrane Transport |

2.7 |

1 |

| 39 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

5.5/28 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−1.6 |

| 43 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

4.78/32 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−1.5 |

| 44 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

4.86/32 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−1.6 |

| 62 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

5.17/32 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−2.3 |

| 63 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

5.03/32 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−3.1 |

| 64 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

5.39/22 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−5 |

| 88 |

Outer membrane protein A |

OmpA |

376393752 |

5.98/38 |

5.46/27 |

Membrane Transport |

1 |

−3.7 |

| 45 |

Outer membrane protein W |

OmpW |

365909926 |

6.17/23 |

5.2/22 |

Membrane Transport |

−4.0 |

1 |

| 18* |

Hypothetical protein HMPREF9694_01670 (tricarboxylic transport) |

TctC |

376400424 |

8.61/35 |

6.7/26 |

Membrane Transport |

−6.5 |

−5.0 |

| 48* |

Hypothetical protein HMPREF9694_01670 (tricarboxylic transport) |

TctC |

376400424 |

8.61/35 |

7.8/29 |

Membrane Transport |

−4.1 |

−8.0 |

| 71* |

Hypothetical protein HMPREF9694_01670 (tricarboxylic transport) |

TctC |

376400424 |

8.61/35 |

8.37/29 |

Membrane Transport |

−10 |

−6.2 |

| 65* |

Carbamoyl phosphate synthase small subunit |

CPSase |

365908404 |

5.79/42 |

5.4/42 |

Nucleotide metabolism |

−2 |

−3.3 |

| 66* |

Multifunctional nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

NdK |

365911711 |

5.55/15 |

5.38/14 |

Nucleotide Metabolism |

−2.6 |

−4.2 |

| 67* |

Nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

NdKs |

376399440 |

5.55/15 |

5.42/14 |

Nucleotide Metabolism |

−1.8 |

−4.1 |

| 89 |

Isochorismatase hydrolase |

|

365909686 |

5.61/24 |

5.36/26 |

Other |

−1.6 |

1 |

| 68 |

Adenosine-3'(2'),5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase |

CysQ |

365908080 |

5.67/28 |

5.31/29 |

Other |

1 |

−2.1 |

| 72 |

Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C |

AHPC |

376395087 |

5.03/21 |

4.95/23 |

Oxido reduction |

−2.3 |

1 |

| 76 |

Superoxide dismutase [Fe] |

FeSOD |

376402095 |

5.75/21 |

5.49/22 |

Oxido reduction |

1 |

3.1 |

| 73 |

Superoxide dismutase [Mn] |

MnSOD |

376396893 |

6.23/23 |

5.84/25 |

Oxido reduction |

1 |

−2.6 |

| 74* |

Superoxide dismutase [Mn] |

MnSOD |

376396893 |

6.23/23 |

6.01/24 |

Oxido reduction |

−2.8 |

−6.3 |

| 75* |

Superoxide dismutase [Mn] |

MnSOD |

376396893 |

6.23/23 |

5.62/24 |

Oxido reduction |

−2 |

−4.5 |

| 11 |

Thiol peroxidase |

TPX |

376401245 |

4.67/18 |

4.8/19 |

Oxido reduction |

1 |

−1.9 |

| 79 |

Chaperonin |

CHA10 |

376396016 |

5.38/10 |

4.97/16 |

Protein metabolism |

1 |

−3.2 |

| 82* |

Elongation factor G |

EF-G |

365907166 |

5.17/77 |

5.62/50 |

Protein metabolism |

1.8 |

1.9 |

| 86* |

Ribosomal protein L1 |

RPL1 |

376396770 |

9.56/25 |

7.77/27 |

Protein metabolism |

−2 |

−2.2 |

| 87* |

Ribosomal protein L1 |

RPL1 |

206564980 |

9.56/25 |

7.56/28 |

Protein metabolism |

−1.7 |

−2.1 |

| 80 |

Ribosomal protein L13 |

RPL13 |

365907069 |

9.60/16 |

8.84/16 |

Protein metabolism |

1 |

−3.9 |

| 85* |

Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase SurA |

SurA |

365908414 |

6.42/47 |

5.68/48 |

Protein metabolism |

−2.1 |

−2.3 |

| 78 |

Autonomous glycyl radical cofactor |

GrcA |

365911773 |

4.82/14 |

4.71/12 |

Stress response |

−1.9 |

1 |

| 69* |

Osmotically-inducible protein Y |

OSMY |

376376350 |

8.67/21 |

5.84/22 |

Stress response |

−3.0 |

−3.7 |

| 47 | Universal stress protein F | USF | 376401205 | 5.46/16 | 5.11/14 | Stress response | −1.5 | 1 |

Fold change refers to normalized spot volumes as calculated by in silico analysis of 2D-DIGE protein maps. Positive and negative values stand for up- and down-regulation in anaerobic growth on FEC, respectively. Protein spots differentially abundant in anaerobic FEC with the respect to both aerobic FEC and anaerobic NAC are marked by an asterisk.

aFunctional classification was performed according to KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

bRelative fold change was measured according to the criteria reported in the experimental section. FEC: Fe(III)-citrate containing medium. NAC: Na(I)-citrate containing medium. +O2: aerobiosis. -O2: anaerobiosis.

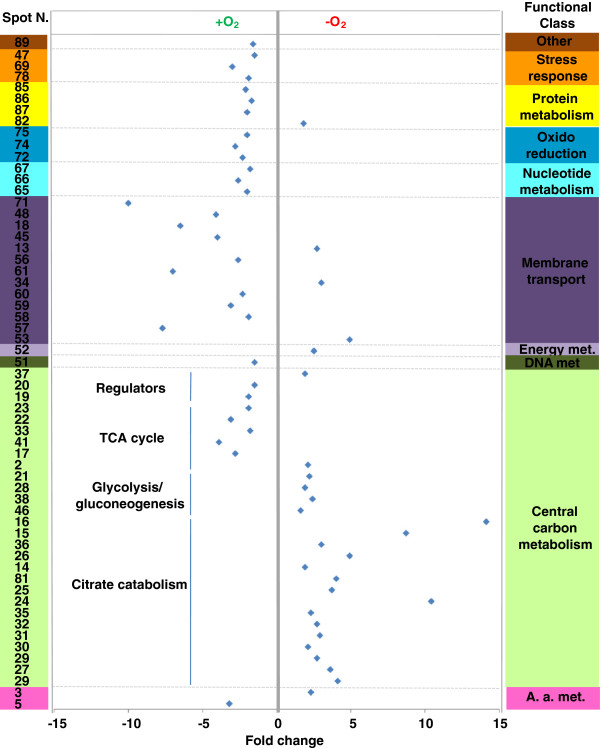

Figure 2.

Functional distribution and abundance fold change (blue diamond) of differentially represented protein spots resulting from the proteomic comparison between anaerobic and aerobic growth on FEC. Fold change and spot number refer to Table 1. A. a. stands for Amino acid. Met. stands for metabolism.

Proteins required for Fe(III)-citrate fermentation

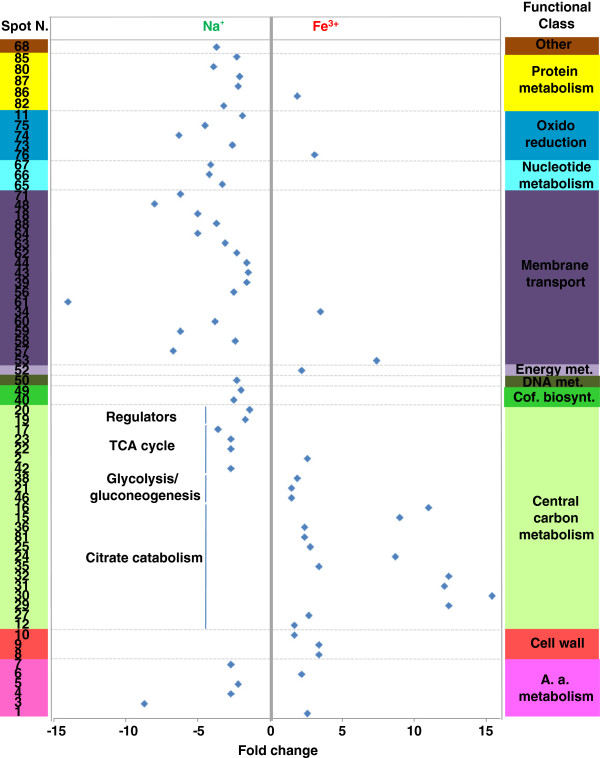

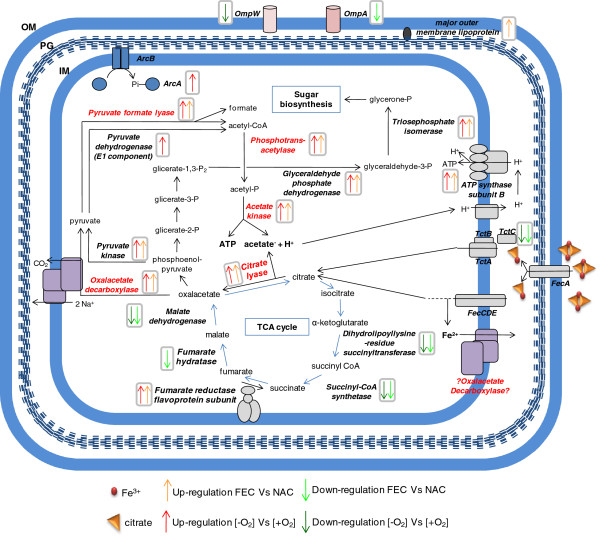

The differential proteomic analysis revealed up-regulation of citrate lyase α- and β-subunit (CitE and CitF), oxaloacetate decarboxylase α-subunit (OadA), pyruvate formate lyase (PFL), phosphotrans-acetylase (PAT) and acetate/propionate kinase (ACK) in anaerobic FEC with respect to both aerobic FEC and anaerobic NAC (Table 1; Figures 2 and 3). These proteins are known to be involved in anaerobic citrate fermentation, eventually converting citrate to acetate with production of ATP. In particular, CitF and CitE are part of the citrate lyase complex, the key enzyme in initiating the anaerobic utilization of citrate, which is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of citrate into acetate and oxaloacetate. The oxaloacetate decarboxylase complex, constituted by alpha, beta and gamma subunits, catalyzes the second step of citrate fermentation by converting oxaloacetate into pyruvate, the latter being the substrate of PFL, a typical enzyme of enterobacteria growing under anaerobic conditions [25], that generates formate and acetyl-CoA. Phosphotrans-acetylase (PAT) catalyzes conversion of acetyl-CoA into acetyl-P, which finally transfers the phosphate group to ADP to yield acetic acid and ATP in the ACK-catalyzed last step of citrate fermentation. Different forms of CitE, CitF, OadA and PFL were identified in K. oxytoca BAS-10 2D-protein maps (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3; Additional file 1 Table S1 and Figure S2). The occurrence of several protein forms having Mw and/or pI different from the predicted one would imply that protein activity could be controlled by post-translational modifications (PTMs), like covalently-bound charged small molecules (as in the case horizontal spot trains) or proteolytic digestion (as in the case of protein isoform with reduced Mw). Indeed, PTMs, like acetylation, succinylation and radical formation have already been shown for PFL activity regulation [26-28], thus giving count for the generation of different protein spots in 2D-maps. In the case of OadA, biotinylation in lysine, reported to be crucial for oxaloacetate decarboxylase activity [29], could explain the slight increase of the measured Mw while the generation of reduced Mw species is likely to be due to proteolytic fragmentation. Concerning CitE and CitF, this is the first study suggesting PTM regulatory events. The differential analysis showed that anaerobic conditions promote citrate fermentation enzymes accumulation, similarly to what already reported in other enterobacteria [10,30,31]. In addition and more interestingly, during BAS-10 anaerobic growth, Fe(III) positively controls the accumulation of citrate fermentative enzymes better than Na(I). In fact, in K. oxytoca BAS-10 citrate fermentation appears much more up-regulated in presence of Fe(III) than Na(I), making this process unique for this microorganism among enterobacteria which usually ferment citrate in a NA(I)-dependent manner [1,8-10].

Figure 3.

Functional distribution and abundance fold change (blue diamond) of differentially represented protein spots resulting from the proteomic comparison between anaerobic growth on FEC and NAC. Fold change and spot number refer to Table 1. A. a. stands for Amino acid. Met. stands for metabolism. Cof. biosynth. stands for Cofactor biosynthesis.

Occurrence of Fe(III) during anaerobic growth also modulated the abundance of many central carbon metabolism enzymes. In particular, pyruvate kinase (PK), glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) were up-regulated whereas TCA cycle enzymes, such as dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase (SucB), malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and fumarate hydratase (FH) were down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to both aerobic FEC and anaerobic NAC (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3). Interestingly, fumarate reductase flavoprotein subunit (FrdA) was up-regulated during the anaerobic growth on FEC with respect to both NAC and aerobic FEC (Figure 4). FrdA is part of complex II homolog menaquinol:fumarate oxidoreductase, which oxidizes menaquinol and transfers the electrons to fumarate during bacterial anaerobic respiration, with fumarate as the terminal electron acceptor [32], thus counteracting TCA cycle down-regulation. Altogether these data suggest that to efficiently divert the carbon flux towards acetate and ATP production citrate fermentation enzymes are up-regulated during anaerobic growth on FEC, whereas TCA cycle enzymes are repressed (Table 1 and Figure 4). In addition, these data indicated that the increased catabolism of citrate throughout a fermentative pathway is coupled to the synthesis of metabolic precursors necessary for anabolic processes like sugar biosynthesis. In particular, the TIM product glycerone-P is a precursor involved in rhamnose biosynthesis (Figure 4). Since rhamnose is the major sugar of EPS [17], the observed TIM up-regulation can represent an interesting link between central carbon metabolites and EPS synthesis in Klebsiella. As a consequence of the increased anaerobic citrate fermentation, the production of acetic acid may also determine an increment of H+ gradient across cell membrane, which positively affects the activity of the ATP synthase complex. In agreement with this view, ATP synthase subunit B was observed as up-regulated under anaerobic conditions in FEC medium, in the respect of both NAC and aerobic FEC (Table 1, Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

Synoptic scheme of metabolic pathways involved in Fe(III)-citrate catabolism. Anabolic routes, regulatory and membrane-associated proteins are also indicated. Reactions are reported according to KEGG [22] and EcoCy [23] databases. OM: outer membrane. PG: peptidoglycan. IM: inner membrane.

Central carbon and nitrogen metabolism key regulators

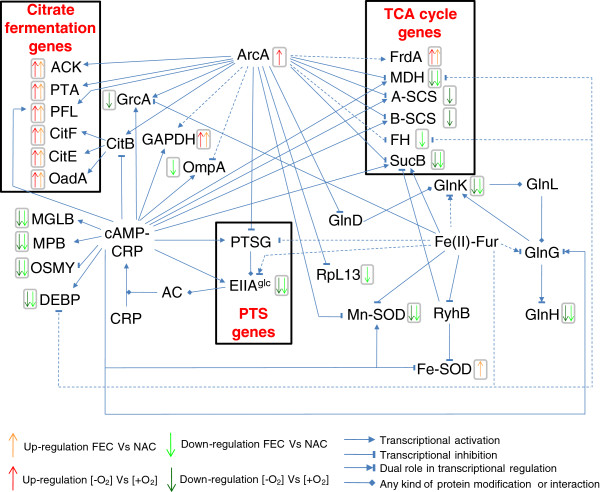

The proteomic comparison showed down-regulation in anaerobic FEC of EIIAGlc, a component of bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP): carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS), which was revealed as two protein spots differing for Mw in 2D-maps (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3; Additional file 1 Table S1 and Figure S2). The differential regulation of EIIAGlc may be related to the differential regulation of central carbon metabolism enzymes. In fact, in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria PTS consists of several factors interacting with different regulatory proteins thus controlling glucose metabolism and many other cellular functions [33]. In particular, EIIAGlc is the central processing unit of carbon metabolism in enteric bacteria since it is involved in the regulation of adenylate cyclase (AC) and therefore in carbon catabolite repression trough the control of the catabolite repressor protein (CRP) (Figure 5). In addition, it also interacts with several non-PTS permeases and glycerol kinase to inhibit their activity (inducer exclusion) [33].

Figure 5.

Regulatory network controlling the expression or the activity ofK. oxytocaBAS-10 differentially abundant proteins. The relationships are reported according to EcoCyc database [23], Bott (1997) [1], Salmon et al. (2005) [34] and Kumar et al. (2011) [49]. Dashed lines refer to an indirect relationship.

Moreover, during anaerobic growth, the down regulation of EIIAGlc may be related to the observed up-regulation of ArcA in FEC with respect to NAC (Table 1; Figures 2 and 3). ArcA, a negative response regulator of genes in aerobic pathways [34,35], is a central regulator of carbon metabolism which, from one hand, negatively controls the expression of pts and of TCA cycle genes [33,36] (Figure 5), and, from the other one, it positively regulates the expression of genes, like citAB, pfl and ack, necessary for fermentative metabolic activities under anaerobic conditions [34,37] (Figure 5). In addition to its role of activator of fermentative genes and inhibitor of aerobic catabolism genes ArcA appears to regulate a wide variety of processes like amino acid and sugar transport and metabolism, cofactor and phospholipids biosynthesis, nucleic acid metabolism [34,38].

Interestingly, the observed down-regulation of EIIAGlc in anaerobic FEC with respect to both NAC and aerobic FEC seemed coupled with a differential regulation of important players of nitrogen and amino acid metabolism. In particular, GlnK, identified as three different spots in K. oxytoca BAS-10 2D-maps (Table 1, Figure 2 and 3; Additional file 1 Table S1 and Figure S2), is part of nitrogen regulatory system (ntr) which facilitates the efficient assimilation of nitrogen from a variety of compounds into glutamine and glutamate as reported in many bacteria like E. coli[39]. The activity of GlnK, which is encoded by an operon encoding the ammonia transporter AmtB too, is controlled by uridylylaton state. In nitrogen proficiency, not-uridylylated GlnK form is the most abundant and interacts with and inhibits AmtB [40]. In nitrogen limitation, uridylylated GlnK inhibits the phosphatase activity of the sensor membrane protein GlnL, that forms a two-component system with the regulatory protein GlnG. Phosphorylated GlnG positively affects the expression of many ntr genes, including GlnK [39,41] (Figure 5). The difference in pI of the GlnK forms here identified gives count for protein uridylylation, which decreases the predicted pI value of native protein form. The protein form with decreased Mw may be due to the possible removal of a N-terminal amino acid stretch as reported in Streptomyces coelicolor[42]. Interestingly, the putative uridylylated GlnK was down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to both anaerobic NAC and aerobic FEC thus suggesting that nitrogen limitation was sensed by BAS-10 growing in anaerobic FEC. The GlnK abundance was in agreement with the down-regulation in anaerobic FEC of carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small subunit (CPSase) in the respect of both NAC and aerobic FEC. In fact, CPSase, an enzymes involved in pyrimidine and arginine biosynthesis, regulates nitrogen disposal by catalyzing synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate from ammonia or glutamine and carbamate [43].

Carbon and nitrogen metabolism could also be associated to the regulation of membrane proteins participating to amino acid up-taking, like the glutamine ABC transporter periplasmic-binding protein (GlnH) and glutamate and aspartate transporter subunit (DEBP), down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to both NAC and aerobic FEC, or arginine 3rd transport system periplasmic-binding protein (ArtJ) and leucine ABC transporter subunit substrate-binding protein (LivK), up-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to both NAC and aerobic FEC. In many bacteria, nitrogen and carbon metabolism are linked to cell energetic state through the conversion of TCA cycle intermediate alpha-ketoglutarate and the amino acid glutamate [44-46]. In K. oxytoca BAS-10 growing in anaerobic FEC, carbon metabolism regulators, like ArcA and CRP, and nitrogen assimilation factors, such as GlnG, could be coordinately controlled (Figure 5) in order to balance amino acid content and to promote biomass accumulation.

Redox balance and stress response proteins

Two isoforms of superoxide dismutase Mn-dependent (Mn-SOD) were down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with the respect to both aerobic FEC and anaerobic NAC (Table 1, Figure 2 and 3; Additional file 1 Table S1 and Figure S2). Mn-SOD is devoted to destroy radicals which are normally produced within the cells. Interestingly and in agreement with what already observed in E. coli[47] and S. typhimurium[48], the presence of iron causes the accumulation of a Fe-SOD whose activity is devoted to contrast iron dependent free radical formation. In particular, Fe-SOD had an abundance level not depending on oxygen, since their relative amount was the same during aerobic and anaerobic growth on FEC. Transcriptional regulation of both SOD genes is reported to be mediated by the Ferric uptake regulator (Fur). Fur controls the transcription of genes, like fecABCDE, involved in iron homeostasis and participates also in the transcriptional regulation of many other genes, such as TCA cycle and PTS genes [49] (Figure 5). Indeed, Fur is mainly a transcriptional repressor when it binds Fe(II). Anyway, by repressing the expression of the non-coding RNA Ryhb, that negatively controls mRNA translation into proteins, consequently Fur may also indirectly exert a positive gene regulatory effect as observed in E. coli[50]. This phenomenon could also occur in K. oxytoca BAS-10 since both fur and ryhb homologues were identified in Klebsiella genus (BLAST analysis, data not shown). Thus, it is likely that the Fe(III)-dependent accumulation of Fe-SOD under anaerobiosis may depend on Fur action to counteract metal toxicity, as observed in E. coli[51].

Furthermore, two proteins, the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (AHPC) and the thiol peroxidase (TPX), contrasting reactive oxygen species (ROS), were differentially regulated in K. oxytoca BAS-10. In particular, AHPC was down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to aerobic FEC, thus revealing an oxygen dependent control, while TPX was down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to anaerobic NAC, thus revealing a Fe(III)-dependent regulation.

Concerning stress associate proteins, the hyperosmotically inducible periplasmic (OSMY) was down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with respect to both aerobic FEC and anaerobic NAC. This protein was found associated with osmotic stress response during E. coli[52]. Other stress associated proteins, like DNA protection during starvation protein (DPS) and the universal stress protein F (USF), were down-regulated in anaerobic FEC with the respect to aerobic FEC showing an oxygen dependent regulation. In DPS, a ferritin-like protein, binds to the chromosome and protects DNA from oxidative damage by sequestering intracellular Fe(III) and storing it in the form of Fe(III)-oxyhydroxide mineral [53].

Proteome data revealed that outer membrane proteins are differentially regulated under anaerobic condition in presence of FEC or NAC. In particular, three isoforms of major outer membrane murein-associated lipoprotein (Lpp), differing in pI value, were up-regulated in anaerobic FEC. In E. coli, Lpp is synthesized as a precursor protein (prolipoprotein) and processed by a signal peptidase after modification with the addition of di-acyl-glycerol and a fatty acid chain [54]. No modification altering pI has been reported up to day being this study the first one suggesting the possibility of such similar PTMs in Lpp. This finding was coupled with the down-regulation of outer membrane OmpA. Indeed, OmpA was revealed as four down-regulated full size isoforms and one and three protein fragments up- and down-regulated in anaerobic FEC, respectively (Table 1). In E. coli OmpA acts as a low permeability porin and it is present in E. coli protein 2D-maps as different protein spots suggesting PTM control [55]. Interestingly, both Lpp and OmpA are reported to interact with PAL that is part of Tol-PAL complex, a membrane-spanning multiprotein system that has been reported playing several functions in Gram-negative bacteria, including transport regulation, cell envelope integrity and pathogenicity [56]. In addition, Lpp has been reported to interact with TonB protein, which serves to couple the cytoplasmic membrane proton motive force to the active transport of iron-siderophore complexes, including the Fec system [57]. The differential regulation of Lpp and OmpA suggests differential roles for these two proteins in controlling iron omeostasis, membrane transport and/or preventing possible cellular damage.

In conclusion, this proteomic analysis revealed an iron-dependent regulation for several stress-related proteins; altogether, these observations suggest the occurrence of different concomitant mechanisms to contrast and/or prevent BAS-10 cell damage during aerobic or anaerobic growth.

Conclusion

At the best of our knowledge, for the first time this study describes at the proteome level biochemical mechanisms allowing the physiological adaptation of the enterobacterium K. oxytoca strain BAS-10 [12,16-18] to sustain anaerobic growth on Fe(III)-citrate as sole carbon and energy source. K. oxytoca BAS-10, isolated from pyrite mine drainages of Colline Metallifere (Tuscany, Italy) and sharing the same ecological niche of specialized bacteria like Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans[58], has the peculiarity of thriving on high concentrations of Fe(III)-citrate. This character distinguishes it from other clinically-isolated enterobacteria, belonging to K. oxytoca, K. pneumonia, S. typhimurium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae species, which are able to uptake and ferment anaerobically citrate as sole carbon and energy source in a Na(I)-dependent manner only [1,10,12,59]. When anaerobically grown on FEC or NAC, K. oxytoca BAS-10 biomass production yields and citrate consumptions were very similar [16]. Under this condition, about half of the initial Fe(III) was reduced to Fe(II) [12,16], the highest levels observed so far with respect to other fermentation processes [60,61].

Differential proteome analyses, carried out using anaerobic FEC as pivotal condition, revealed two sets of proteins whose abundance is O2- and Fe(III)-dependent, respectively. The cross checking of these proteome data revealed proteins whose abundance is specifically associated to anaerobic growth on Fe(III). Interestingly, these data portrayed a coordinated regulation of citrate catabolic enzymes during anaerobic growth on FEC. Citrate may enter the cell throughout several kind of permeases, including Cit transporters [1,10], TctABC [3] and FecABCDE systems [4-7]. Then, it is catabolised via the TCA cycle or the citrate fermentation pathway under aerobic or anaerobic growth, respectively. Under anaerobic conditions, the first pathway is repressed, while the second one is favoured. In addition, a fascinating speculation is that one BAS-10 citrate fermentation enzyme, the oxalacetate decarboxylase, can be adapted to act as both Fe(II)- and Na(I)-depending pump to excrete Fe(II) and Na(I). This hypothesis has to be verified by functional studies on BAS-10 oadGAB genes. Furthermore, PK, GAPDH and TIM abundance levels suggested an increased synthesis of metabolic precursors necessary for anabolic processes, such as those yielding rhamnose, linking together central carbon metabolism and EPS biosynthesis in Klebsiella. Differential regulation of metabolic enzymes was associated with variable cellular levels of carbon metabolism key regulators ArcA and PTS EIIAGlc, and important players of nitrogen and amino acid metabolism, like GlnK. In this context, ArcA plays a central role in regulating anaerobic carbon metabolism by controlling the expression of citrate fermentation and TCA cycle enzymes directly or indirectly – i.e. throughout PTS gene regulation – and nitrogen metabolism (Figure 5). Furthermore, during anaerobic FEC growth, ArcA-dependent gene regulation may be combined to iron effect on gene expression trough the activity of Fur (Figure 5). Proteome results also suggest that metabolic pathway modulation seems coupled with regulation of redox balance, stress response and outer membrane protein content. The occurrence of various proteins involved in these processes is finely balanced to face iron and pH toxicity, thus allowing K. oxytoca BAS-10 to survive in extreme habitats. Altogether, these data well correlate with previous observations on other microorganisms able surviving in highly polluted environments [62,63] or extremophile organisms living under extreme conditions [64,65], both generally activating multiple intracellular processes devoted to contrast environmental toxic effects and optimize energy production.

According to the results presented here, K. oxytoca BAS-10 faces high iron concentration by various molecular adaptation mechanisms, which are summarized in Figures 4 and 5. The coordinated regulation of metabolic pathways and cellular networks allows K. oxytoca BAS-10 to efficiently sustain bacterial growth by adapting metabolic and biochemical processes in order to face iron toxicity and to ensure optimization of energy production. In this context, EPS production is intrinsically related to bacterial biomass production and metabolic and energy supply for anabolic reactions. Since K. oxytoca BAS-10 was proven to have a high potential for biotechnological applications [18-20], the data presented here could be used for redesigning fermentation strategies that are difficult to be intuitively identified and approaching novel genetic targets to be engineered for a rational design of high-yielding EPS producer strains.

Methods

Bacterial cultivation and metal binding exopolysaccharide (EPS) quantification

For K. oxytoca BAS-10 cultures, two defined media were prepared containing the same mineral composition (2.5 g NaHCO3, 1.5 g NH4Cl, 1.5 g MgSO4.7H2O, 0.6 g NaH2PO4, 0.1 g KCl, buffered at pH 7.6 with NaOH) and 50 mM Na-citrate (14.7 g.l-1), named NAC medium, or 50 mM ferric citrate (13.15 g.l-1), named FEC medium, as the sole carbon and energy source. BAS-10 was retrieved from cryovials kept at −80°C in 25% glycerol in Nutrient Broth (NB) (Difco). One ml aliquots of dense (abs600nm = 1.4) overnight NB pre-culture of BAS-10 were used to inoculate (1:100 v:v) FEC or NAC medium cultivations. Aerobic cultivations were performed in flasks, aerated by a magnetic stir bar (250 r.p.m.). Anaerobic cultivations were performed in pirex bottles, previously fluxed with N2 and kept under anaerobiosis by sealed cap. Aerobic and anaerobic cultivations were performed in parallel quadruplicates, at 30°C. Biomass samples for proteomic analysis were harvested by centrifugation at late exponential growth stages. i.e. after 36 and 72 h of incubation in aerobic and anaerobic cultivations, respectively. For EPS extraction and quantification, the procedures described by Baldi et al. (2009) [12] were followed.

Phylogenetic analysis

One microliter of diluted (1:10 in autoclaved distilled water) BAS-10 bacterial suspension was used for PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene by using fD1 and rD1 universal primers [66] and 1.5 units of recombinant Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s specifications. To perform bacterial cell lysis and DNA denaturation, a treatment of 5 min, at 95 °C, was performed. Then, amplification steps were carried out for 40 cycles consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C and 2 min at 72 °C, with a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR fragments were purified by using PCR clean-up kit (NucleoSpin, Macherey-Nagel) according to manufacturer’s specifications and sequenced with the same primers at BMR Genomics (University of Padova, Italy).

BAS-10 16S rDNA sequence was compared using BLAST probing [67] of DNA sequences from the NCBI database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?CMD=Web&PAGE_TYPE=BlastHome) with default parameters, selecting either only cultivable reference strains (refseq_rna) or whole database strains (rn/nt). ClustalX program [68] was used to align the homologous 16S rDNA gene sequences obtained from the database, choosing the slow/accurate method for pairwise alignment. All positions containing alignment gaps were eliminated in pairwise sequence comparisons by selecting the related option. The 16S rDNA sequence of Streptomyces tendae was used as outgroup. Alienated sequences were then used to generate rooted trees throughout Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) algorithm.

Protein extraction

Total proteins were extracted from frozen biomass samples of quadruplicated cultivations per each condition by using an experimental procedure previously described [69,70]. Briefly, pellets were cleaned three times with a washing solution (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 4 mg/ml leucopeptin, 0.7 mg/ml pepstatin, 5 mg/ml benzamidin). Following re-suspension in washing solution containing 0.3% SDS, bacterial cells were disrupted by sonication on ice (output control 4, 4 x 15 s, Vibra Cell, USA). Samples were then boiled (5 min) and rapidly cooled down on ice (15 min). DNase (100 μg/ml) and RNase (50 μg/ml) were added in ice for 20 min. Cell debris and non-broken cells were separated by centrifugation at 15,000 x g, for 15 min, at 4°C. Protein solutions were dialyzed against distilled water for 3 h, at 4°C, precipitated by using 3 vol of acetone, at −20°C, overnight, and re-suspended in 30 mM Tris pH 8.5, 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% w/v CHAPS.

2D-DIGE analysis

Proteomes of K. oxytoca BAS-10 grown in FEC medium under anaerobiosis [−O2 and aerobiosis [+O2 or in NAC under [−O2 conditions were compared, using FEC medium under [−O2 as pivotal condition. To this aim, protein samples were labelled for 2D-DIGE analysis using CyDyeTM DIGE minimal labelling kit (GE Healthcare, Sweden), as previously described [71]. Briefly, protein samples (40 μg) were labelled with 320 pmol of CyDye on ice in the dark for 30 min. Labelling reaction was stopped by addition of 0.8 μl of 10 mM lysine and incubation was continued on ice for 15 min., in the dark. Two samples out of a total of four per each condition were labelled using Cy3 dye and the other two using Cy5 dye to account for florescence bias. In addition, a standard protein pool was generated by combining an equal amount of protein extracts from which six 40 μg protein aliquots were then minimally labelled with 320 pmol Cy2 fluorescent dye (CyDyeTM DIGE, GE Healthcare), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Thus, a total of six 2D-DIGE gels were performed containing a mix of Cy2-labeled pooled protein standard and Cy3- and Cy5-labeled protein samples from cells incubated in FEC medium under [−O2 and [+O2 and in NAC under [−O2 conditions, analysed in couples, i.e. FEC [−O2vs FEC [+O2, FEC [−O2vs NAC [−O2 and FEC [+O2vs NAC [−O2. For IEF, DeStreak rehydration solution (GE Healthcare), containing 0.68% v/v IPG buffer (GE Healthcare) and 10 mM DTT (Sigma), was added to each mix up to a 340 μl final volume. IEF was performed as previously described [57] using 4–7 pH range 18 cm-IPG strips (GE Healthcare) in an Ettan IPGphor III apparatus (GE Healthcare). After IEF, IPG strips were incubated with an equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 30% v/v glycerol, 2% w/v SDS, 0.05 M Tris–HCl, pH 6.8) containing 2% w/v DTE for 10 min; thiol groups were then blocked by further incubation with equilibration buffer containing 2.5% w/v iodoacetamide. Focused proteins were then separated by using 12% SDS-PAGE, at 10°C, in a Hettan Dalt six (GE Healthcare), with a maximum setting of 40 μA per gel and 110 V.

Protein visualization and image analysis

The 2D-gels were scanned with a DIGE imager (GE Healthcare) to detect cyanin-labeled proteins, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Differential gel analysis was performed automatically by using the Image Master 2D Platinum 7.0 DIGE software (GE Healthcare), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein spots were automatically detected and then matched. Individual spot abundance was automatically calculated from quadruplicated 2D-gels as mean spot volume, i.e. integration of optical density over spot area, and normalized to the Cy2-labeled internal pooled protein standard. Protein spots showing more than 1.5 fold change in spot volume (increased for up-regulation or decreased for down-regulation), with a statistically significant ANOVA value (P ≤ 0.05), were considered differentially represented and further identified by MS analysis.

Protein identification

Protein spots were excised from the 2D-gels, alkylated, digested with trypsin and identified as previously reported [56]. Peptide mixtures were desalted by μZip-TipC18 (Millipore, MA) using 50% v/v acetonitrile/5% v/v formic acid as eluent before MALDI-TOF-MS and nLC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS analysis.

In the case of MALDI-TOF-MS experiments, peptide mixtures were loaded on the MALDI target, by using the dried droplet technique, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix, and analyzed using a Voyager-DE PRO mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, USA) operating in positive ion reflectron, with an acceleration voltage of 20 kV, a N2 laser (337 nm) and a laser repetition rate of 4 Hz [72]. Final mass spectra, measured over a mass range of 700–4000 Da and obtained by averaging 400–800 laser shots, were elaborated using the DataExplorer 5.1 software (Applied Biosystems) and manually inspected to get the corresponding peak lists. Internal mass calibration was performed with peptides deriving from trypsin autoproteolysis. Tryptic digests were eventually analyzed by nLC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS using a LTQ XL mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA) equipped with a Proxeon nanospray source connected to an Easy-nanoLC (Proxeon, Odense, Denmark) [73,74]. Peptide mixtures were separated on an Easy C18 column (10–0.075 mm, 3 μm) (Proxeon). Mobile phases were 0.1% v/v aqueous formic acid (solvent A) and 0.1% v/v formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B), running at total flow rate of 300 nL/min. Linear gradient was initiated 20 min after sample loading; solvent B ramped from 5% to 35% over 15 min, from 35% to 95% over 2 min. Spectra were acquired in the range m/z 400–1800. Acquisition was controlled by a data-dependent product ion scanning procedure over the 3 most abundant ions, enabling dynamic exclusion (repeat count 2 and exclusion duration 60 s); the mass isolation window and collision energy were set to m/z 3 and 35%, respectively.

MASCOT search engine version 2.2.06 (Matrix Science, UK) was used to identify protein spots from an updated NCBI non-redundant database by using MALDI-TOF-MS and nLC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS data and by selecting trypsin as proteolytic enzyme, a missed cleavages maximum value of 2, Cys carbamidomethylation and Met oxidation as fixed and variable modification, respectively. In the first case, a mass tolerance value of 40–80 ppm was selected; in the second case, a mass tolerance value of 2 Da for precursor ion and 0.8 Da for MS/MS fragments was chosen. MALDI-TOF-PMF candidates with a MASCOT score > 83 or nLC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS candidates with more than 2 assigned peptides with an individual MASCOT score > 25, both corresponding to P < 0.05 for a significant identification, were further evaluated by the comparison with their calculated mass and pI values, using the experimental data obtained from 2D-DIGE.

Abbreviations

2D-DIGE: 2D-Differential Gel Electrophoresis; MS: Mass Spectrometry; FEC: Fe(III)-Citrate; NAC: Na(I)-Citrate; EPS: Exopolysaccharide; PTM(s): Post-Translational Modification(s); AC: Adenylate Cyclase; CRP: Catabolite Repressor Protein.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

GG carried out 16S rDNA amplification, phylogenetic analysis, 2D-DIGE analysis, gene ontology and wrote the draft manuscript. FB designed and performed BAS10 cultivations and helped to wrote the draft manuscript. GR carried out protein MS-identification. MG helped to performe BAS10 cultivations. AC helped to perform 16S rDNA amplification, phylogenetic analysis and 2D-DIGE experiments. AS supervised protein MS-identification and revised the manuscript. AMP conceived and supervised the study and participated in its design and coordination and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table S1:containing mass spectrometry parameters of K. oxytoca BAS-10 differentially abundant protein identification;Figure S1:showing phylogenetic tree generated by using 16S rDNA sequence ofK. oxytocaBAS-10 and the first twenty hits from a BLAST analysis performed by selecting whole database strains; Figure S2 showing 2D-protein maps, chosen as examples of anaerobic FEC, anaerobic NAC and aerobic FEC condition, respectively. Labels indicating differentially abundant protein spots and referring to Table 1 and Table 1 are also reported in Figure S2; Figure S3: containing distribution into functional classes of the identified protein spots, according to KEGG metabolic database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), from the comparison between anaerobic and aerobic growth on FEC from the comparison between anaerobic growth on FEC and NAC, respectively; 1447 nt gene sequence generated from BAS-10 16S rDNA. (DOC 1711 kb)

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Gallo, Email: giumir@msn.com.

Franco Baldi, Email: baldi@unive.it.

Giovanni Renzone, Email: giovanni.renzone@ispaam.cnr.it.

Michele Gallo, Email: baldi@unive.it.

Antonio Cordaro, Email: giuseppe.gallo@unipa.it.

Andrea Scaloni, Email: andrea.scaloni@ispaam.cnr.it.

Anna Maria Puglia, Email: a.maria.puglia@unipa.it.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by Italian Ministery of Education, University and Research (MIUR, ex 60%) to AMP and by funds from the “Rete di Spettrometria di Massa della Regione Campania (RESMAC)” to AS. GG was supported by the European-funded project “LAntibiotic Production: Technology, Optimization and improved Process” (LAPTOP), KBBE-245066.

References

- Bott M. Anaerobic citrate metabolism and its regulation in enterobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:78–88. doi: 10.1007/s002030050419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kästner CN, Dimroth P, Pos KM. The Na+-dependent citrate carrier of Klebsiella pneumoniae: high-level expression and site-directed mutagenesis of asparagine-185 and glutamate-194. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s002030000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnen B, Hvorup RN, Saier MH. The tripartite tricarboxylate transporter (TTT) family. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:457–465. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härle C, Kim I, Angerer A, Braun V. Signal transfer through three compartments: transcription initiation of the Escherichia coli ferric citrate transport system from the cell surface. EMBO J. 1995;14:1430–1438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. Iron uptake by Escherichia coli. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1409–s1421. doi: 10.2741/1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visca P, Leoni L, Wilson MJ, Lamont IL. Iron transport and regulation, cell signalling and genomics: lessons from Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1177–1190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Herrmann C. Docking of the periplasmic FecB binding protein to the FecCD transmembrane proteins in the ferric citrate transport system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6913–6918. doi: 10.1128/JB.00884-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott M, Meyer M, Dimroth P. Regulation of anaerobic citrate metabolism in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:533–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pos KM, Dimroth P. Functional properties of the purified Na(+)-dependent citrate carrier of Klebsiella pneumoniae: evidence for asymmetric orientation of the carrier protein in proteoliposomes. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1018–1026. doi: 10.1021/bi951609t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kästner CN, Schneider K, Dimroth P, Pos KM. Characterization of the citrate/acetate antiporter CitW of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Arch Microbiol. 2002;177:500–506. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder I, Johnson E, de Vries S. Microbial ferric iron reductases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:427–447. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi F, Marchetto D, Battistel D, Daniele S, Faleri C, De Castro C, Lanzetta R. Iron-binding characterization and polysaccharide production by Klebsiella oxytoca strain isolated from mine acid drainage. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1241–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DB, Hallberg KB. The microbiology of acidic mine waters. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:466–473. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Toril E, Llobet-Brossa E, Casamayor EO, Amann R, Amils R. Microbial ecology of an extreme acidic environment, the Tinto River. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4853–4865. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4853-4865.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaby N, Dold B, Pfeifer HR, Holliger C, Johnson DB, Hallberg KB. Microbial communities in a porphyry copper tailings impoundment and their impact on the geochemical dynamics of the mine waste. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:298–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi F, Minacci A, Pepi M, Scozzafava A. Gel sequestration of heavy metals by Klebsiella oxytoca isolated from iron mat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;36:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone S, De Castro C, Parrilli M, Baldi F, Lanzetta R. Structure of the iron-binding exopolysaccharide produced anaerobically by the gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella oxytoca BAS-10. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;31:5183–5189. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi F, Marchetto D, Paganelli S, Piccolo O. Bio-generated metal binding polysaccharides as catalysts for synthetic applications and organic pollutant transformations. N Biotechnol. 2011;29:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas F, Alves VD, Reis MA. Advances in bacterial exopolysaccharides: from production to biotechnological applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Annibale A, Leonardi V, Federici E, Baldi F, Zecchini F, Petruccioli M. Leaching and microbial treatment of a soil contaminated by sulphide ore ashes and aromatic hydrocarbons. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:1135–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0749-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLAST. http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

- KEGG. http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/kegg2.html.

- EcoCyc. http://ecocyc.org.

- ExPASy. http://www.expasy.org.

- Knappe J, Blaschkowski HP, Groebner P, Schmitt T. Pyruvate formate lyase of Escherichia coli: the acetyl enzyme intermediate. European J. 1974;50:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A, Fritz-Wolf K, Kabsch W, Knappe J, Schultz S, Volker Wagner AF. Structure and mechanism of the glycyl radical enzyme pyruvate formate-lyase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:969–975. doi: 10.1038/13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sprung R, Pei J, Tan X, Kim S, Zhu H, Liu CF, Grishin NV, Zhao Y. Lysine acetylation is a highly abundant and evolutionarily conserved modification in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:215–225. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800187-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Tan M, Xie Z, Dai L, Chen Y, Zhao Y. Identification of lysine succinylation as a new post-translational modification. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E, Oesterhelt D, Reinke H, Beyreuther K, Dimroth P. The sodium ion translocating oxalacetate decarboxylase of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sequence of the biotin-containing alpha-subunit and relationship to other biotin-containing enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9640–9645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Matsumoto F, Oshima T, Fujita N, Ogasawara N, Ishihama A. Anaerobic regulation of citrate fermentation by CitAB in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:3011–3014. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheu PD, Witan J, Rauschmeier M, Graf S, Liao YF, Ebert-Jung A, Basché T, Erker W, Unden G. CitA/CitB two-component system regulating citrate fermentation in Escherichia coli and its relation to the DcuS/DcuR system in vivo. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:636–645. doi: 10.1128/JB.06345-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CP, Hansen AK, Cotter P, Gunsalus RP. Effect of cell growth rate on expression of the anaerobic respiratory pathway operons frdABCD, dmsABC, and narGHJI of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6599–6605. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6599-6605.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon KA, Hung SP, Steffen NR, Krupp R, Baldi P, Hatfield GW, Gunsalus RP. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12: effects of oxygen availability and ArcA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15084–15096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpica R, Sandoval GR, Rodríguez C, Franco B, Georgellis D. Signaling by the arc two-component system provides a link between the redox state of the quinone pool and gene expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:781–795. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JY, Kim YJ, Cho N, Shin D, Nam TW, Ryu S, Seok YJ. Expression of ptsG encoding the major glucose transporter is regulated by ArcA in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38513–38518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawers G, Suppmann B. Anaerobic induction of pyruvate formate-lyase gene expression is mediated by the ArcA and FNR proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3474–3478. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3474-3478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalel-Levanon S, San KY, Bennett GN. Effect of ArcA and FNR on the expression of genes related to the oxygen regulation and the glycolysis pathway in Escherichia coli under microaerobic growth conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:147–159. doi: 10.1002/bit.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwkamp TA, Ninfa AJ. Physiological role of the GlnK signal transduction protein of Escherichia coli: survival of nitrogen starvation. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:203–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boogerd FC, Ma H, Bruggeman FJ, van Heeswijk WC, García-Contreras R, Molenaar D, Krab K, Westerhoff HV. AmtB-mediated NH3 transport in prokaryotes must be active and as a consequence regulation of transport by GlnK is mandatory to limit futile cycling of NH4(+)/NH3. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwkamp TA, Ninfa AJ. Antagonism of PII signalling by the AmtB protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1017–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldvogel E, Herbig A, Battke F, Amin R, Nentwich M, Nieselt K, Ellingsen TE, Wentzel A, Hodgson DA, Wohlleben W, Mast Y. The PII protein GlnK is a pleiotropic regulator for morphological differentiation and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92:1219–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden HM, Thoden JB, Raushel FM. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: an amazing biochemical odyssey from substrate to product. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:507–522. doi: 10.1007/s000180050448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commichau FM, Forchhammer K, Stülke J. Regulatory links between carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninfa AJ, Jiang P. PII signal transduction proteins: sensors of alpha-ketoglutarate that regulate nitrogen metabolism. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Ninfa AJ. Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein controlling nitrogen assimilation acts as a sensor of adenylate energy charge in vitro. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12979–12996. doi: 10.1021/bi701062t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrac S, Touati D. Fur-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of FeSOD expression in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2002;148:147–156. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxell B, Fink RC, Porwollik S, McClelland M, Hassan HM. The Fur regulon in anaerobically grown Salmonella enterica sv. typhimurium: identification of new Fur targets. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Shimizu K. Transcriptional regulation of main metabolic pathways of cyoA, cydB, fnr, and fur gene knockout Escherichia coli in C-limited and N-limited aerobic continuous cultures. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpica R, Sandoval GR, Rodríguez C, Franco B, Georgellis D. Signaling by the arc two-component system provides a link between the redox state of the quinone pool and gene expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:781–795. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecerek B, Moll I, Afonyushkin T, Kaberdin V, Bläsi U. Interaction of the RNA chaperone Hfq with mRNAs: direct and indirect roles of Hfq in iron metabolism of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:897–909. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Kögl SA, Jung K. Time-dependent proteome alterations under osmotic stress during aerobic and anaerobic growth in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7165–7175. doi: 10.1128/JB.00508-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Kolter R. Protection of DNA during oxidative stress by the nonspecific DNA-binding protein Dps. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5188–5194. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5188-5194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugai M, Wu HC. Export of the outer membrane lipoprotein is defective in secD, secE, and secF mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2511–2516. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2511-2516.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EM, Nair U, Phadke ND, Maddock JR. Proteomic screening and identification of differentially distributed membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1029–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlewska R, Wiśniewska K, Pietras Z, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK. Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (Pal) of Gram-negative bacteria: function, structure, role in pathogenesis and potential application in immunoprophylaxis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;298:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs PI, Letain TE, Merriam KK, Burke NS, Park H, Kang C, Postle K. TonB interacts with nonreceptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1640–1648. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.6.1640-1648.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi F, Olson GJ. Effects of Cinnabar on Pyrite Oxidation by Thiobacillus ferrooxidans and Cinnabar Mobilization by a Mercury-Resistant Strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:772–776. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.772-776.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Faou AE, Morse SA. Characterization of a soluble ferric reductase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Biol Met. 1991;4:126–131. doi: 10.1007/BF01135390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley DR. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:259–287. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.259-287.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz M, Brune A, Schink B. Anaerobic and aerobic oxidation of ferrous iron at neutral pH by chemoheterotrophic nitrate-reducing bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s002030050555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrendt AJ, Tollaksen SL, Lindberg C, Zhu W, Yates JR 3rd, Nevin KP, Babnigg G, Lovley DR, Giometti CS. Steady state protein levels in Geobacter metallireducens grown with iron (III) citrate or nitrate as terminal electron acceptor. Proteomics. 2007;7:4148–4157. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RH, Xiong AS, Xue Y, Fu XY, Gao F, Zhao W, Tian YS, Yao QH. Microbial biodegradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:927–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ji X, Zhou Z, Wang Y, Zhang X. Thermus thermophilus proteins that are differentially expressed in response to growth temperature and their implication in thermoadaptation. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:855–864. doi: 10.1021/pr900754y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesbah NM, Wiegel J. Life at extreme limits: the anaerobic halophilic alkalithermophiles. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1125:44–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Alduina R, Renzone G, Thykaer J, Bianco L, Eliasson-Lantz A, Scaloni A, Puglia AM. Differential proteomic analysis highlights metabolic strategies associated with balhimycin production in Amycolatopsis balhimycina chemostat cultivations. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Renzone G, Alduina R, Stegmann E, Weber T, Lantz AE, Thykaer J, Sangiorgi F, Scaloni A, Puglia AM. Differential proteomic analysis reveals novel links between primary metabolism and antibiotic production in Amycolatopsis balhimycina. Proteomics. 2010;10:1336–1358. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Lo Piccolo L, Renzone G, La Rosa R, Scaloni A, Quatrini P, Puglia AM. Differential proteomic analysis of an engineered Streptomyces coelicolor strain reveals metabolic pathways supporting growth on n-hexadecane. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;94:1289–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio C, Arena S, Salzano AM, Renzone G, Ledda L, Scaloni A. A proteomic characterization of water buffalo milk fractions describing PTM of major species and the identification of minor components involved in nutrient delivery and defense against pathogens. Proteomics. 2008;8:3657–3666. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scippa GS, Rocco M, Ialicicco M, Trupiano D, Viscosi V, Di Michele M, Arena S, Chiatante D, Scaloni A. The proteome of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) seeds: discriminating between landraces. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:497–506. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Verrillo F, Renzone G, Arena S, Rocco M, Scaloni A, Marra M. Response to biotic and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis thaliana: analysis of variably phosphorylated proteins. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1934–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1:containing mass spectrometry parameters of K. oxytoca BAS-10 differentially abundant protein identification;Figure S1:showing phylogenetic tree generated by using 16S rDNA sequence ofK. oxytocaBAS-10 and the first twenty hits from a BLAST analysis performed by selecting whole database strains; Figure S2 showing 2D-protein maps, chosen as examples of anaerobic FEC, anaerobic NAC and aerobic FEC condition, respectively. Labels indicating differentially abundant protein spots and referring to Table 1 and Table 1 are also reported in Figure S2; Figure S3: containing distribution into functional classes of the identified protein spots, according to KEGG metabolic database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), from the comparison between anaerobic and aerobic growth on FEC from the comparison between anaerobic growth on FEC and NAC, respectively; 1447 nt gene sequence generated from BAS-10 16S rDNA. (DOC 1711 kb)