Abstract

This paper describes the use of action research in a patient conference to provide updated hereditary cancer information, explore patient and family member needs and experiences related to genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA), elicit feedback on how to improve the GCRA process, and inform future research efforts. Invitees completed GCRA at City of Hope or collaborating facilities and had a BRCA mutation or a strong personal or family history of breast cancer. Action research activities were facilitated by surveys, roundtable discussions, and reflection time to engage participants, faculty, and researchers in multiple cycles of reciprocal feedback. The multimodal action research design effectively engaged conference participants to share their experiences, needs, and ideas for improvements to the GCRA process. Participants indicated that they highly valued the information and resources provided and desired similar future conferences. The use of action research in a patient conference is an innovative and effective approach to provide health education, elicit experiences, identify and help address needs of high-risk patients and their family members, and generate research hypotheses. Insights gained yielded valuable feedback to inform clinical care, future health services research, and Continuing Medical Education (CME) activities. These methods may also be effective in other practice settings.

Introduction

Genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA) is a process of genetic counseling, genetic testing (when indicated), and providing personalized cancer risk management recommendations for patients and families, accompanied by psychosocial support [1–3]. GCRA is usually provided by a genetic counselor or advanced practice nurse along with a medical oncologist, surgeon, or geneticist [4]. In the past decade, this consultative service has become standard of care for individuals whose personal or family history is suggestive of a hereditary predisposition to cancer. The most common hereditary cancer syndrome for which GCRA is offered is hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, primarily caused by mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. In the GCRA setting, the relationship between the GCRA team and the patient typically ends after genetic test results are discussed with the patient. In most clinical settings, limited resources preclude additional GCRA appointments on a routine basis.

While there is growing literature showing that, for most patients, GCRA promotes adoption of effective risk management practices without triggering clinical levels of distress, most of these studies did not investigate long-term effects of GCRA [5–10]. Studies of BRCA carriers conducted a few months to a few years after genetic test result disclosure found that patients may experience a range of other psychosocial impacts, such as changes in body image, stress, anxiety, feelings of guilt, and the need to communicate with others outside the family regarding genetic test results and risk-reduction decisions [11,12]. Longer-term studies have also found that these patients desire additional services such as peer-to-peer support, partner education, additional family involvement in the testing process, and follow-up genetic counseling visits [13–17].

Support groups have been suggested as a way to help address the needs of various patient groups including BRCA carriers; however, several studies have shown a low level of interest in support groups among BRCA carriers [18–20]. National organizations such as Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE) and Bright Pink have emerged offering Internet resources, information, and support for BRCA carriers [21,22], however, not all patients have access to the Internet or feel comfortable using it. Additionally, Internet resources may not satisfy patient needs for further direct contact with their genetics providers. Clearly, additional modalities are needed to efficiently meet patients’ expressed need for long-term follow-up after GCRA.

Since its establishment in 1996, the Cancer Screening & Prevention Program Network (CSPPN) at City of Hope in Duarte, California, has delivered GCRA services to more than 7,000 at-risk families [4]. The CSPPN employs a one or two visit GCRA model. The first visit includes genetic counseling, personalized risk assessment, and informed consent if genetic testing is pursued. The second visit includes a discussion of test results and individualized cancer risk management recommendations. The majority of patients seen through the CSPPN also elect to participate in an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved registry that allows for continued contact through long-term follow up questionnaires. While our general procedure is to address the questions and needs identified through these questionnaires on a patient-by-patient basis, we observed that many patients had similar needs for ongoing information and support after completion of the risk assessment and genetic testing process [17]. We decided to use an action research approach within a patient conference to address identified needs and generate additional dynamic cycles of feedback and shared interactions between and among patients, family members and clinician researchers.

An Action Research Framework to Address and Explore Patient Needs

Action research is a broad style of research without one specific method. It is a cyclical process of inquiry, feedback, reflection, and informed action [23,24]. It involves cycles of interaction between and among researchers and participants throughout the study, the incorporation of participant input, and contribution to social change [25]. It is also often used to help improve professional practices [26]. In contrast to conventional approaches to research, the primary objectives of action research are the co-generation of knowledge and problem solving through the direct engagement of stakeholders in the research process. Introduced in the social sciences in the 1930s and practiced in the field of education for decades, the use and recognized value of action research in healthcare settings have increased in recent years [27,25,28–31]. We hypothesized that the dynamic, reciprocal interactions engendered by an action research methodology would help our clinical research team better understand and respond to the long-term needs of GCRA patients. In this paper we describe the incorporation of action research into the development, design, and delivery of an interactive patient conference to address and further explore the post-GCRA needs of patients with increased risk for breast and/or ovarian cancer.

Methods

Conference Planning and Development

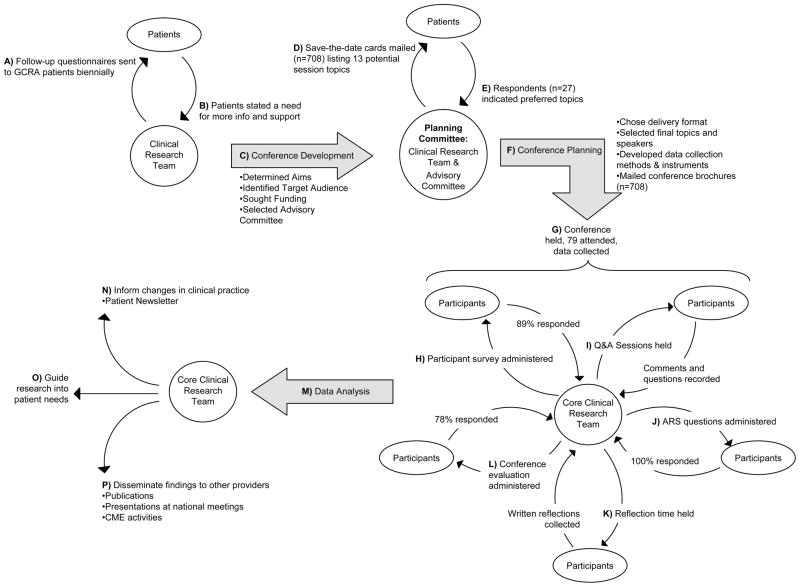

Figure 1 illustrates the multiple cycles of inquiry, feedback, reflection, and action that contributed to this action research project. The first action research cycle for the patient conference began when an interdisciplinary clinical research team of five experts in the field of clinical cancer genetics (three genetic counselors, a PhD nurse credentialed in genetics, and a medical oncologist/geneticist) convened to review patient follow-up questionnaires (Figure 1A,B), formulate the overall aims, and define the target audience. The team also met to secure funding to make the conference accessible to all eligible patients and families free of charge, and to identify additional members to represent an interdisciplinary conference advisory committee (Figure 1C). Six additional professionals were added to the clinical research team to form the conference planning committee: a genetic counselor who directs a community-based GCRA program, a clinical psychologist, a cancer genetics clinical research associate, a breast cancer patient advocate, and a representative of the local branch of the American Cancer Society. The planning committee convened three times over a six month period. As illustrated in Figure 1D–F, the conference planning (delivery format, session topics and speakers, marketing, methods, and instruments for data collection) was guided by another cycle of action research that incorporated patient feedback and the expertise of the planning committee.

Fig 1.

Patient conference action research process. This schema illustrates the flow of inquiry, feedback, and action between the clinician researchers and patients/conference participants. Curved arrows represent the flow of information and feedback between the clinical research team and key stakeholders. Straight arrows represent action taken by the clinical research team.

GCRA: genetic cancer risk assessment

Conference Description and Structure

The aims of the conference, titled “Closing the Loop and Opening Vistas: A Day for Patients and Families Coping with Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk,” were to: (1) address patient questions and needs identified through our initial cycles of inquiry by providing updates in risk assessment, genetic testing, cancer screening, and prevention care for individuals and families with increased cancer risk; (2) further explore patient experiences, needs, and ideas to improve the GCRA process; (3) connect patients and their families with the GCRA team, additional experts in the field, relevant community resources, and to each other, and (4) identify and catalyze further heredity cancer research initiatives that are informed by patient-centered feedback and outcomes.

A one-day delivery format was chosen. The agenda (Table 1) included podium presentations, small group break-out sessions, and a patient advocacy forum to provide the information, updates, and support requested by patients on follow-up questionnaires (Figure 1A,B) and save-the-date response cards (Figure 1E). All presentations were designed to include question and answer sessions to facilitate discussions among participants and presenters. A roundtable session with use of an Audience Response System (ARS, Audience Response Systems, Inc., Evansville, IN) and a reflection time (described below) were chosen to prompt cycles of interaction and feedback between participants and presenters.

Table 1.

Conference Agenda

| 8:00 am | Sign-In/Continental Breakfast |

| Health Fair: Exhibits and Community Resources (open all day) | |

| 9:00 am | Welcome |

|

| |

| 9:15 am | Clinical Cancer Genetics: New discoveries, new tools and surviving well |

| Introduction | |

| Medical Oncologist/Geneticist | |

| Breast Cancer Screening: Recommendations and Advances | |

| Radiologist | |

| Reducing Risk through Surgery: Options, Techniques, and Reconstruction Choices | |

| Plastic Surgeon | |

| Ovarian Hormones and Cancer Risk in the BRCA Carrier | |

| Medical Oncologist/Geneticist | |

| Choices and Consequences | |

| Psychologist | |

| Questions and Answers | |

|

| |

| 11:00 am | Breakout Session I (Choose One) |

| Young Women’s Issues: When Menopause Comes Early, Balancing Fertility and Cancer Risk Management | |

| Gynecologic Oncologist and a Medical Oncologist | |

| Family Relationships and Coping with Risk | |

| Psychologist and a PhD Nurse Credentialed in Genetics | |

| Genetics 101: Review of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risks, and Inheritance | |

| Genetic Counselor | |

| Genetics, Discrimination, and the Law: Should I be Concerned? | |

| Lawyer specializing in cancer patient issues | |

|

| |

| 12:00 pm | Lunch - Roundtable Session |

| What We’ve Learned From You | |

| Medical Oncologist/Geneticist | |

| What Do You Want Your Doctors To Know? | |

| Audience response system with open-mike | |

|

| |

| 1:15 pm | Breast Cancer Advocacy: How it Works, What Can I do to Help? |

| Breast Cancer Patient Advocate Panel | |

|

| |

| 2:00 pm | Reflection Time |

| Writing activity for attendees to explore their experiences & opinions on various topics | |

|

| |

| 2:30 pm | Breakout Session II (Choose One) |

| Better BRCA Tests, New Genes, More Confusion, and Taking Advantage of the Defective BRCA Gene in Cancer Treatment | |

| Medical Oncologist/Geneticist | |

| Lifestyle and Risk: Diet, Exercise, Body Size | |

| Epidemiologist | |

| Spouses and Partners: Working Together to Deepen Emotional Connections | |

| Social Worker Director of City of Hope’s Patient Resource Center | |

|

| |

| 3:00 pm | Closing Remarks, Ice Cream Reception, and Raffle |

| 4:00 pm | End of Program |

A health and resource fair with exhibitors from cancer-related organizations was also planned to help address patient requests for additional information and support. A list of 22 local and national organizations that provide information and/or support to individuals with, or at risk for, breast or ovarian cancer were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the patient conference with an exhibit table, at no charge. Sixteen organizations agreed to provide an exhibit.

Session Topic and Speaker Selection

Potential topics for presentations and break-out sessions were generated by members of the planning committee based on patient feedback from follow-up surveys (Figure 1A–C). A needs assessment was conducted by mailing a pre-addressed postage-paid card to eligible patients (Figure 1D) that listed 13 potential topics and also served as a “save-the-date” card for the conference. Invitees were asked to return the card indicating their interest in attending and their top four topic preferences (Figure 1E). Eight of the thirteen topics were incorporated based on this feedback (Figure 1F), with core medical management topics as podium presentations and other topics as break-out sessions (Table 1). Experts in various fields relevant to the care and management of BRCA carriers from City of Hope and other top cancer centers, who were best suited to address the patient information and support needs identified through this cycle of action research, were invited to present on the selected topics. Speakers included a medical oncologist-geneticist, breast radiologist, plastic surgeon, psychologist, gynecologic oncologist, medical oncologist, PhD nurse credentialed in genetics, genetic counselor, lawyer, research scientist, and social worker.

Five breast cancer advocates were invited and formed a distinguished panel to provide a forum to discuss the roles of, and how to participate in, patient advocacy. Most panel members lead or are involved with multiple local or national organizations, including the Los Angeles Breast Cancer Alliance, the California Breast Cancer Research Program, the National Breast Cancer Coalition, Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the Avon Breast Cancer Foundation, the State of California Breast Cancer Research Program, the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, the Kommah Seray Inflammatory Breast Cancer Foundation, FORCE, You Are Not Alone, and the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Biomedical Information Group.

Conference Invitees

Invitees were selected from an IRB-approved prospective hereditary cancer registry database which includes patients seen at City of Hope, St. Joseph Hospital, Mission Hospital, and Saddleback Memorial Medical Center, all located in Southern California. Inclusion criteria for invitees were English-speaking patients seen for GCRA between 1996 and 2009 who were found to have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene abnormality (mutation or variant of uncertain significance (VUS)) or who had a strong personal or family history of breast cancer and negative BRCA test results. Spanish-speaking patients were invited to a separate conference conducted in Spanish (manuscript in process). Patients were invited to bring adult family members and/or friends to the conference. Conference brochures were mailed to the invitees in February 2009 (Figure 1F). An automated calling system was used to deliver a message informing the recipient of the conference and directing the recipient to the conference Website or to call City of Hope for more information or to register. Grant funding allowed the conference to be held at no cost to all attendees.

IRB approval was obtained to measure the outcomes of the conference; consent was implied by patients registering for and attending the conference. In order to protect confidentiality, registration materials explicitly sought assent for video recording. Additionally, an announcement was made at the beginning of the conference stating that it was being video recorded and encouraging participants to not give their names when speaking or asking questions during the conference.

Instruments

All data collection instruments were developed by the clinical research team and revised based on feedback from members of the advisory committee (Figure 1F). An 18-item participant survey was developed to be administered to all participants as they signed in on the day of the conference. The first six items were applicable to all conference attendees, and included four demographics items (age, gender, and two items on cancer history), and multiple choice questions eliciting participants’ reason for attending and what they hoped to gain from attending the conference. Attendees who had been seen for GCRA were asked an additional 12 multiple choice questions regarding their GCRA experience, perceptions about genetic discrimination, and cancer risk management decisions.

Six questions were developed for use with an ARS during the lunch round table session to elicit participant feedback about the GCRA process (listed in Table 2). The ARS is an interactive, computer-driven question and answer data collection system that allows participants to individually and anonymously respond to questions via hand-held remote devices. Group responses can be immediately displayed in graph format on a screen, to be reviewed and discussed as a group. Five open-ended follow-up questions were also developed to be asked after each ARS question for participants to respond to in an open-mike format.

Table 2.

Audience Response System (ARS) and Open-mike Questions

| Question | Responses | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Generally we provide two consultation visits for genetic counseling and testing. Would you have liked another visit with us after your genetic test results disclosure session? (N=68) | A. Yes | 42 (61.8) |

| B. No | 6 (8.8) | |

| C. Not another appointment, but more information and resources | 20 (29.4) | |

|

| ||

| 2. Did you find the information given during genetic counseling overwhelming? (N=69) | A. Yes | 17 (24.6) |

| B. No | 22 (31.9) | |

| C. Some of the information was overwhelming, but not all | 30 (43.5) | |

|

| ||

| *What would help make the experience less overwhelming? | “an opportunity to talk with other women who were gene positive…to get information from them, maybe their own experience” | |

|

| ||

| 3. What kinds of information do you think you need more of? | ||

|

| ||

| a. Hereditary cancer risks (what types of cancer am I at risk for and how high are the risks)? (N=72) | A. Yes, I need more information | 51 (70.8) |

| B. No, I don’t need more information | 21 (29.2) | |

|

| ||

| b. Screening for and preventing cancer (what are the best ways to reduce risk)? (N=72) | A. Yes, I need more information | 53 (73.6) |

| B. No, I don’t need more information | 19 (26.4) | |

|

| ||

| c. The genetics of hereditary cancer (how is cancer risk inherited and what are the risks for family members)? (N=75) | A. Yes, I need more information | 45 (60.0) |

| B. No, I don’t need more information | 30 (40.0) | |

|

| ||

| *Do you have other information needs? | “some way for you to transmit to the people…the latest understandings every 6 months, every 12 months” | |

|

| ||

| 6. Did the genetic counseling process cause anxiety or worry for you? (N=71) | A. Yes | 42 (59.2) |

| B. No | 29 (40.8) | |

|

| ||

| *What about the process caused anxiety or worry? (i.e., too much information, information was complex, timing of the visit, what the info told me about my risk/about family risk, other) | “it was more about, what does this mean for the rest of the family my sisters, nieces, as well as what that means for me…for child bearing later on” | |

|

| ||

| *Did it cause any anxiety issues for family members? | “…the BRCA gene was passed on by our father’s side…he was never diagnosed with cancer, so for him the guilt was a lot.” | |

|

| ||

| *If you were to do the genetic counseling and testing process over, is there anything that we have not addressed that could be changed? If so, what? | “When you get the results, you’re really in a fog. Maybe if you know the person is going to get positive test results that you can give them time to digest it before you show them all those graphs.” | |

Open-mike questions and sample responses are in italics.

Ten questions (listed in Table 3) were developed to elicit qualitative feedback from participants about their feelings, coping mechanisms, and experiences related to their cancer risk during a 30-minute reflection time. Each question was printed on a large sheet of poster paper and placed on the walls of a smaller conference room to allow participants to write their reflections on the corresponding poster. Background relaxation music was selected to create a calm atmosphere. Blank 3x5 cards and collection boxes were also prepared for participants who preferred to share their reflections privately.

Table 3.

Reflection Time Questions

| Question | Responses (N) | Example Responses |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What has helped you cope with your cancer risk? | 16 | “Family, friends, and laughter” “Information--gives me power & options; faith-- gives me strength & wellness; friends & family-- give me hope” |

| 2. What about your cancer risk has been the most difficult to cope with? | 16 | “Leaving my children without a mother’s wisdom if I were to die early, & that horrible legacy of risk” “Not knowing about side effects (emotional and physical) that...interfere with regular life--especially those related to intimacy” |

| 3. Reflecting on how you have dealt with your cancer risk, what are you most proud of? | 18 | “My positive attitude and how I inspire others” “Never losing my sense of humor & my belief in the presence of God in all my trials” |

| 4. What message would you give to someone who just found out they have a BRCA mutation? | 17 | “Be calm, relax, seek knowledge. You don’t have to decide everything today” “You are still BEAUTIFUL and COMPLETE” |

| 5. What have you learned about yourself through coping with your cancer risk? | 14 | “I can still laugh! And I love DEEPER” “I can help others by educating them to be proactive” |

| 6. How has your family changed through learning about your cancer risk? | 16 | “Some members are no longer members, and some members are the best people I know” “We are even closer--life is precious!” |

| 7. Some families use humor to help cope with challenges. Have you or your family found humor to be helpful in coping with cancer risk? In what ways? | 8 | “Family thought it hilarious every time I burned a wig!” “Had a lot of fun barrettes to put on my wigs during chemo with young children” |

| 8. What has helped you talk to family members about cancer risk? | 10 | “Knowing that being pro-active is key!” “I lost my mother & I don’t want my children to lose theirs” |

| 9. What barriers have you run into talking with family members about cancer risk? | 11 | “People who want to bury their heads in the sand and the others who don’t want to share their results that could benefit others (selfish). Ahh!!” “Guilt and fear of information” |

| 10. What are your favorite resources for BRCA carriers and/or cancer survivors? | 5 | FORCE, American Cancer Society, City of Hope, ACOR lists, Johns Hopkins Website |

Note: The above questions were printed on large sheets of paper and posted around the reflection time room. Conference attendees were invited to write their responses to the questions on the posters or on 3x5 cards to be deposited in a confidential box provided.

A nine-item conference evaluation survey was designed to be distributed at the end of the conference. The survey items (listed in Table 4) included five questions using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, to elicit participant satisfaction, and four open-ended questions requesting feedback about the conference and future topics desired.

Table 4.

Results of Conference Evaluations

| Question | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Today’s conference met my expectations | Strongly Agree | 38 (64.4) |

| Agree | 19 (32.2) | |

| Disagree | 0 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | |

| Unsure | 2 (3.4) | |

|

| ||

| The topics covered issues that I am interested in | Strongly Agree | 35 (57.4) |

| Agree | 24 (39.3) | |

| Disagree | 0 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | |

| Unsure | 2 (3.3) | |

|

| ||

| I will be able to use information I learned today in the future | Strongly Agree | 35 (58.3) |

| Agree | 23 (38.3) | |

| Disagree | 0 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | |

| Unsure | 2 (3.3) | |

|

| ||

| I will be able to use resources I gained today | Strongly Agree | 36 (60.0) |

| Agree | 24 (40.0) | |

| Disagree | 0 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | |

| Unsure | 0 | |

|

| ||

| I would like to attend a conference like this again | Strongly Agree | 39 (63.9) |

| Agree | 21 (34.4) | |

| Disagree | 0 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | |

| Unsure | 1 (1.6) | |

|

| ||

| What topics would you like to see covered in future conferences? | Open ended response | |

|

| ||

| If you came to another conference, who would you want to bring with you? | Open ended response | |

|

| ||

| Is there anything about today’s conference that you think should be changed? | Open ended response | |

Data Analysis

Quantitative analyses, including descriptive statistics of survey data and ARS responses, were completed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). All conference proceedings were recorded. Recordings that contained participant comments, including question and answer sessions and the open-mike responses between the ARS questions, were transcribed verbatim for future qualitative analyses (Figure 1M).

Results

The conference was held at City of Hope’s Cooper Auditorium on March 21, 2009, from 8 am to 4 pm (Figure 1G). Selection criteria identified 708 previous patients to receive invitations. Of these, 105 (15%) were returned due to incorrect addresses resulting in a total of 603 effective invitations sent. One hundred eighteen individuals registered for the conference (20%) and of those, 79 (67%) attended. As described in Table 5, the 79 attendees included patients, friends, and family members. Eighty-nine percent (70/79) of attendees completed the participant survey (Figure 1H). Of these, 84% were female, mean age was 48 years (range: 26–74), 57% reported a personal history of cancer (of which 88% had breast cancer and 20% had ovarian cancer). Sixty-four percent of respondents had a BRCA mutation, 4% had a BRCA VUS, and 22% were friends or family members of patients.

Table 5.

Demographic characteristics and cancer history of conference attendees who completed the participant survey

| Attendee Demographics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| All Conference Attendees | 79 | -- |

| Completed participant survey | 70 | 88.6 |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| Mean | 48 | -- |

| Range | 26–74 | -- |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 59 | 84.3 |

| Male | 10 | 14.3 |

| Not reported | 1 | 1.4 |

|

| ||

| Participant category | ||

| BRCA carrier | 45 | 64.3 |

| Individuals with a VUS | 3 | 4.3 |

| Relative of a BRCA carrier | 9 | 12.9 |

| Friend/partner of a BRCA carrier | 6 | 8.6 |

| Other* | 6 | 8.6 |

| Not reported | 1 | 1.3 |

|

| ||

| Participant cancer history | ||

| Personal history of 1 or more cancers | 40 | 57.1 |

| Breast | 35 | 87.5 |

| Ovarian | 8 | 20.0 |

| Skin | 5 | 12.5 |

| Lung | 1 | 2.5 |

| Prostate | 1 | 2.5 |

| Uterine | 1 | 2.5 |

| Other** | 5 | 12.5 |

BRCA = BRCA1 or BRCA 2; VUS = variant of uncertain significance

Other includes a patient advocate, relative/spouse of patient with inconclusive results, and non-BRCA carriers who were invited due to their requests for additional information.

Other cancers reported include 2nd primary breast, cervical, and bladder.

The conference opened with a continental breakfast and a health fair with 16 community resource exhibits, followed by four podium presentations providing medical management updates and a discussion of choices and consequences for BRCA carriers (Table 1). A central aim of the conference was to complete the first cycle of action research by addressing patient needs for information and support identified through patient questionnaires (Figure 1A) and indicated on responses to the survey on save-the-date cards (Figure 1E). Participants could choose to attend two of six small group interactive break-out sessions offered. Podium presentations and break-out sessions were each followed by a question and answer session where participants could submit questions to the presenters on 3x5 cards or via microphone (Figure 1I). A roundtable luncheon session allowed faculty to share information gained through patient participation in the hereditary cancer research registry and engaged participants in providing feedback on their genetic counseling experience using the ARS and open-mike format (Figure 1J). All 79 participants responded to at least some of the ARS questions and many shared personal experiences, needs, or ideas for improvement, related to their GCRA experience, during the open-mike time. A patient advocate panel shared examples and discussed the role of advocacy for breast cancer survivors and their families. The reflection time invited participants to share their thoughts and feelings on questions related to the psychosocial aspects cancer risk and read their peers’ reflections while listening to relaxation music (Figure 1K). An average of 13 responses was recorded for each of the 10 reflection time questions (range 5–18). Example responses for each question are listed in Table 3. All of these inquiries to conference attendees initiated another cycle of action research (Figure 1I–K).

As summarized in Table 4, of the 62 conference evaluations completed (78% response rate; Figure 1L), nearly all respondents reported that the conference met their expectations (97%) and covered topics they were interested in (97%), that they would be able to use information (97%) and resources (100%) gained at the conference, and that they would like to attend a similar type of conference again (98%). Topics participants most frequently requested to be addressed in future conferences were: advances and/or updates in treatment, prevention, and research (n=12); female sexuality and how to cope after having breasts and/or ovaries removed (n=6); and information for the next generation such as prevention measures (n=4). The individuals most attendees would bring with them to a future conference were spouses or significant others and daughters (n=25). The most commonly mentioned changes to the conference format requested by attendees were to provide PowerPoint handouts of presentations (n=8), and allow for longer sessions (n=6). Only two participants reported that there was too much information or that some of it was too technical.

Discussion

Previous research within our own patient population and others clearly demonstrates that carriers of a BRCA mutation have continued needs for information and support after completion of the GCRA process [13–17]. FORCE has conducted several annual conferences specifically for BRCA mutation carriers; however, to date there are no published data exploring the experiences, perceptions, and ongoing needs of FORCE conference attendees. In addition, many individuals are not able to travel to other parts of the country to attend such conferences. Another one-day conference was held for BRCA carriers in the Vermont region [32]. While several instruments were administered to attendees of this conference, patient experiences with the genetic counseling and testing process, their ongoing needs, or how these needs might be addressed, were not reported. To our knowledge, no previous patient conference has used action research to directly link professional and lay education with a cycle of reciprocal feedback between patients, advocates, and providers.

This study demonstrates that interactions generated by an action research-based patient conference uniquely allow for information dissemination from clinicians and researchers to patients, as well as feedback gathering from patients to clinicians and researchers. Through podium presentations and small group breakout sessions, attendees were provided with updates on cancer risk and risk management, as well as psychological support and resources pertinent to their previously expressed needs. The ARS enhanced the lecture-based component of the conference by providing an interactive way for the participants to discuss their experience with GCRA and what can be done to improve the process. The ARS was particularly effective at engaging the conference attendees (100% participated). This may be attributed to its anonymous nature as well as the appeal of seeing and discussing the graphic display of aggregated participant responses immediately after a question was posed. As illustrated in Table 2, the supplementary open-mike questions were especially fruitful in eliciting the specific needs and experiences of these patients and their families. For example, one male participant asked about counseling for spouses: “How do you support someone that has this mutation and being able to say the right things and not say the wrong things?” Allowing participants to comment on their experiences on large posters during the reflection time gave them the opportunity to share and build on each other’s comments and to support each other through their insights on shared experiences. For example, in response to the question shown in Table 3, “What message would you give to someone who just found out they have a BRCA mutation?” one participant said, “Be calm, relax, seek knowledge. You don’t have to decide everything today.” The breakout sessions also helped address patients’ previously expressed needs for emotional support, through activities and group discussions led by a clinical psychologist or social worker, while generating more data directly from the participants about their support and information needs.

Data from the conference are being used to inform strategies for meeting long-term post-GCRA needs of our patients. For example, in follow-up questionnaires completed prior to the conference and at the conference, many patients mentioned a desire to receive periodic updates regarding cancer screening and prevention for those at increased risk of breast and/or ovarian cancer. During the open-mike time, the idea of a patient newsletter was suggested. This feedback was used to develop an annual newsletter sent to our patients with the updates they have requested (Figure 1N). The first issue included a report on the patient conference and some of the conference findings. The insights into patient needs and experiences are also being used to revise our GCRA process in general (Figure 1N) and are being shared with cancer genetics professionals through peer-reviewed publications and continuing medical education (CME) activities, including our Intensive Course in Cancer Risk Assessment [33,34], as a step toward “closing the loop” between patient needs and patient care (Figure 1P). These educational activities are designed to foster best practices in cancer genetics and personalized medicine, in alignment with highest standards of excellence in CME [35] and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) vision for lifelong medical professional learning that is focused on improving patient care and population health [36]. The patient newsletter is just one step toward addressing these additional needs and others are in progress. For example, findings from the conference are also informing the development of future patient and health services research questions (Figure 1O). Since fertility, menopausal, family communication, and other psychosocial well-being concerns were identified among the attendees, members of the conference planning committee are examining these issues in reproductive age women at high risk for breast or ovarian cancer [37].

We have shown this method of embedding multimodal action research in a patient conference to be effective in addressing the needs of this patient group and learning more about their needs and experiences. This method is also a natural venue for learning from and providing support to other patient groups, including cancer survivors, since 57% of attendees of this conference were cancer survivors and many of their issues go far beyond genetics.

The clinical research team is conducting thematic analysis [38] of all qualitative data from Q&A sessions, ARS discussion, and the reflection time to probe deeper into the unique questions and concerns of this patient population in order to identify areas for additional patient-centered research.

Limitations

The participants in this conference represent a high-risk clinic-based population from one region of the country, which may limit the generalizability of these findings; however, the needs expressed by this group of BRCA carriers were similar to those previously reported [16,13,15,14]. It is also important to note that data were gathered from a subset of our patient population who were available and motivated to attend the conference. In an effort to reduce bias resulting from participant reluctance to voice their concerns, several opportunities were provided at the conference for participants to provide comments or feedback anonymously; however, it is possible that patients who did not feel comfortable voicing their opinions or who had a negative GCRA experience chose not to attend the conference.

General limitations of the patient conference method are cost and time. This conference was funded by grants, which allowed us to provide the conference free of charge to all participants. Charging a registration fee could present a barrier to attendance for patients with limited financial resources. Although the conference format was more efficient than seeing each patient individually for an additional follow-up appointment (and allowed each patient to receive much more information and support than could have been compressed into a single one-hour appointment), planning and holding a large conference is time consuming. Development of a standardized format with materials that can be easily updated could reduce the time investment in preparing similar events. A formal cost-benefit analysis is needed in future studies to supplement outcome and satisfaction data.

Conclusion and Implications

Previous research and feedback given by patients seen for GCRA on long-term follow-up questionnaires demonstrate a need for ongoing information and support after the GCRA process is complete. Since it is not possible to offer additional follow-up appointments to all patients, this project sought to develop a novel way to address the expressed needs of this patient group and learn more about their specific needs and experiences related to GCRA. This study demonstrates the practical utility and value of employing an action research approach within a one-day patient conference where key stakeholders–the patients, their families, and the interdisciplinary clinical research team–can explore and address post-GCRA needs and share information, resources, and support for patients with a BRCA mutation and their families.

Insights gained from this conference are guiding our approach to clinical care and post-GCRA communication, including the distribution of an annual patient newsletter to help address patients’ ongoing information needs. Consistent with the IOM goals for patient-centered professional development, the insights and knowledge gained from this conference are also being disseminated through CME activities to help other GCRA clinicians “close the loop” between patients and providers. Additionally, findings from the conference are informing future research efforts related to patient needs and the GCRA process. The use of action research methodology within a patient conference, with information distribution and patient feedback, may serve as a model to help address the needs of patients in other practice settings.

Acknowledgments

This conference was funded by grants provided by the Regents of the University of California, Breast Cancer Research Program and Susan G. Komen for the Cure, Los Angeles County. The City of Hope Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network is supported by Award Number RC4 CA153828 (PI: J. Weitzel) from the National Cancer Institute and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to acknowledge the conference faculty, Dr. James Anderson, Karen Clark, Dr. Katherine Henderson, Kory Jasperson, Matthew Loscalzo, Joanna Morales, Dr. Joanne Mortimer, Dr. Lalit Vora, and Dr. Mark Wakabayashi, for their contributions of time and expertise. We would also like to thank Shawntel Payton and Tracy Sulkin for assistance with manuscript preparation, Gloria Nunez for help with conference coordination, and the rest of the Division of Clinical Cancer Genetics for providing logistical support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state that they have no financial relationship with the funders.

References

- 1.Weitzel JN. Genetic cancer risk assessment: Putting it all together. Cancer. 1999;86(Suppl 11):2483–2492. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991201)86:11+<2483::aid-cncr5>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trepanier A, Ahrens M, McKinnon W, et al. Genetic cancer risk assessment and counseling: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2004;13 (2):83–114. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGC.0000018821.48330.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palomares MR, Paz IB, Weitzel JN. Genetic cancer risk assessment in the newly diagnosed breast cancer patient is useful and possible in practice. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):3165–3166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.157. author reply 3166–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald DJ, Blazer KR, Weitzel JN. Extending comprehensive cancer center expertise in clinical cancer genetics and genomics to diverse communities: the power of partnership. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8 (5):615–624. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braithwaite D, Emery J, Walter F, et al. Psychological impact of genetic counseling for familial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Cancer. 2006;5 (1):61–75. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-2577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitzel JN, McCaffrey SM, Nedelcu R, et al. Effect of genetic cancer risk assessment on surgical decisions at breast cancer diagnosis. Arch Surg. 2003;138 (12):1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerman C, Croyle RT, Tercyak KP, et al. Genetic testing: Psychological aspects and implications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70 (3):784–797. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelps C, Wood F, Bennett P, et al. Knowledge and expectations of women undergoing cancer genetic risk assessment: a qualitative analysis of free-text questionnaire comments. J Genet Couns. 2007;16 (4):505–514. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metcalfe A, Werrett J, Burgess L, et al. Cancer genetic predisposition: information needs of patients irrespective of risk level. Fam Cancer. 2009;8 (4):403–412. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Brzosowicz J, et al. Experiences of genetic counseling for BRCA1/2 among recently diagnosed breast cancer patients: a qualitative inquiry. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26 (4):33–52. doi: 10.1080/07347330802359586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotser CB, Boehmke M. Survivorship considerations in adults with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome: state of the science. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3 (1):21–42. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald DJ, Sarna L, Weitzel JN, et al. Women’s perceptions of the personal and family impact of genetic cancer risk assessment: Focus group findings. J Genet Couns. 2010;19 (2):148–160. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metcalfe KA, Liede A, Hoodfar E, et al. An evaluation of needs of female BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers undergoing genetic counselling. J Med Genet. 2000;37 (11):866–874. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.11.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metcalfe KA, Liede A, Trinkaus M, et al. Evaluation of the needs of spouses of female carriers of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Clin Genet. 2002;62 (6):464–469. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Prospero LS, Seminsky M, Honeyford J, et al. Psychosocial issues following a positive result of genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: findings from a focus group and a needs-assessment survey. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;164 (7):1005–1009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner-Lin A. Formal and informal support needs of young women with BRCA mutations. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26 (4):111–133. doi: 10.1080/07347330802359776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habrat D, MacDonald DJ, Lagos V, et al. Assessing Patients’ Perceptions of Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment and Post Counseling Needs. Paper presented at the City of Hope Eugene and Ruth Roberts Summer Student Academy; Duarte, CA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thewes B, Meiser B, Tucker M, et al. The unmet information and support needs of women with a family history of breast cancer: A descriptive study. J Genet Couns. 2003;12 (1):61–67. doi: 10.1023/A:1021447201809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamann HA, Croyle RT, Smith KR, et al. Interest in a Support Group Among Individuals Tested for a BRCA1 Gene Mutation. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;18 (4):15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorval M, Maunsell E, Dugas MJ, et al. Support Groups for People Carrying a BRCA Mutation. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;165 (6):740–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed February 3 2010];Bright Pink. 2009 Available at: http://www.bebrightpink.org/

- 22.FORCE: Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered, Inc. [Accessed February 3, 2010];2009 Available at: http://www.facingourrisk.org/

- 23.Sagor R. Guiding School Improvement with Action Research. Vol. 100047. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; Alexandria, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost P. Principles of the action research cycle. In: Ritchie R, Pollard A, Frost P, editors. Action Research: a Guide for Teachers - Burning Issues in Primary Education. National Primary Trust; Birmingham, England: 2002. pp. 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. Br Med J. 2000;320 (7228):178–181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNiff J, Whitehead J. All you need to know about action research. SAGE; London, Thousand Oaks, Calif: 2006. Ch 4: Where did action research come from? pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mander R, Cheung NF, Wang X, et al. Beginning an action research project to investigate the feasibility of a midwife-led normal birthing unit in China. J Clin Nurs. 2009;19:517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spetz A, Henriksson R, Salander P. A Specialist Nurse as a Resource for Family Members to Patients With Brain Tumors: An Action Research Study. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:E18–26. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305741.18711.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gresty K, Skirton H, Evenden A. Addressing the issue of e-learning and online genetics for health professionals. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9 (1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison B, Lilford R. How can action research apply to health services? Qual Health Res. 2001;11 (4):436–449. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong DK, Chow SF. Beyond clinical trials and narratives: a participatory action research with cancer patient self-help groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60 (2):201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKinnon W, Naud S, Ashikaga T, et al. Results of an intervention for individuals and families with BRCA mutations: A model for providing medical updates and psychosocial support following genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2007;16 (4):433–456. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blazer K, Sand S, Hilario J, et al. Using action research to evaluate and innovate a program of personalized cancer genetics training for personalized medicine. Paper presented at the AACE International Cancer Education Conference: The Art and Science of Cancer Education and Evaluation; Houston, TX. Joint Annual Meeting for AACE CPEN EACE.2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazer KR, MacDonald DJ, Culver JO, et al. Personalized cancer genetics training for personalized medicine: Improving community-based healthcare through a genetically literate workforce. Genet Med. 2011;13 (9):832–840. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821882b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ACCME . [Accessed June 1, 2010];ACCME Guide to the Accreditation Process: Demonstrating the Implementation of the ACCME’s Updated Accreditation Criteria. 2009 Available at: http://www.accme.org/index.cfm/fa/AccreditationProcess.home/AccreditationProcess.cfm.

- 36.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald DJ, Hurley K, Garcia N, et al. Psychosocial Well-Being in Ethnically Diverse Reproductive Age BRCA+ Women. Paper presented at the International Society of Nurses in Genetics 24th Annual Education Conference; Montreal, Canada. Oct 17 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3 (2):77–101. [Google Scholar]