Abstract

Background

The growth in the use of anti-TNF-α agents for treatment of inflammatory conditions has led to increased recognition of the side effects associated with this class of drugs.

Case Description

We report a case of a patient who developed erythema multiforme (EM) major with characteristic oral and cutaneous lesions following treatment with the anti-TNF-α medication infliximab therapy for Crohn’s Disease (CD).

Clinical Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of infliximab-induced EM secondary to the treatment of CD. It is important for dental clinicians evaluating patients using anti-TNF-α agents to be aware of this possible complication.

The number of patients treated with medications that neutralize tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α such as infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira), has increased over the last decade because of the long-term efficacy and effectiveness of these agents.1 This includes patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, and ulcerative colitis. Although anti-TNF-α therapy is generally well tolerated,2–5 adverse serious cutaneous and oral reactions have been reported with the use of the fully humanized monoclonal adalimumab including hypersensitivity reactions, demyelinating disease, a lupus-like reaction, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and erythema multiforme (EM) major.6,7 Colombel et al.5 reported an incidence of 4–22% infusion reactions to infliximab. The majority of patients discontinued further infliximab drug therapy. In a safety and efficacy study of infliximab for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis2, four patients in the infliximab arm (N = 201) developed serious adverse reactions. One developed drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and a second patient discontinued treatment due to pleurisy, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, SLE, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Two additional patients developed uveitis after dose escalation of infliximab. Clearly, these drugs, although efficacious and safe for the vast majority of patients suffering from immune-related inflammatory conditions, have a significant risk for secondary immune reactivity.

As noted above, SJS and EM major have been associated with anti-TNF-α use. As of 2008, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had received twenty-one reports of adult patients with severe cutaneous adverse reactions associated with infliximab, including EM (15 cases), SJS (5 cases), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TENS).8 Also, severe cutaneous reactions have been reported with etanercept and adalimumab.

Although EM/SJS/TENS reactions to anti-TNF-α agents are well documented by the FDA, the literature is sparse with regard to the publication of such cases related to infliximab and negligible with regard oral lesions. While there have been 21 infliximab-induced EM/SJS/TENS cases reported to the FDA, a review of the literature did not reveal the publication of such cases within the medical literature. Only Ahdout et al., and Salama and Lawrance noted the issue of major oral involvement, and all previous such cases were reported within medical journals with the focus upon the cutaneous lesions. Both the Ahdout et al., 2010, and the Salama and Lawrance (2009) case reports noted oral involvement of EM/SJS reactions to adalimumab therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of Infliximab-induced EM secondary to the treatment of CD. This report details the presentation of a woman who presented with oral mucosal and cutaneous lesions consistent with EM major following treatment with infliximab for CD.

Case Report

A 39-year-old Caucasian female, diagnosed with CD in 1996, was referred for evaluation of oral ulcerations that developed after a dental prophylaxis four weeks earlier. She reported that this was the second time she had developed oral lesions after visiting the dentist. Unlike the outbreak following the first dental visit, new oral ulcerations continued to erupt after initial lesion development. The intraoral lesions increased in number, size and severity compared to the first eruption, and involved the buccal mucosa, labial mucosa and tongue. There was a corresponding increase in her pain level. The oral lesions worsened after she received an infusion of infliximab one week later, for the treatment of CD. That infliximab infusion would end up being her last, which was approximately one month prior to being examined by the NIH dental clinic.

The patient’s CD was diagnosed in 1996 and treated with azathioprine (Imuran) until 2006, with good control of her symptoms. In 2006, azathioprine was discontinued for an anticipated pregnancy. Postpartum, the drug was restarted, but the patient was subsequently hospitalized on two occasions for extreme “flares” of the gastrointestinal tract and joints symptoms believed to be rheumatoid arthritis. Sixty-five mg daily of prednisone was started, but discontinued due to side effects. In late 2008, the patient began treatment with 285 mg of (IV) infliximab every two months. Prior to the onset of her oral and cutaneous symptoms, she did not have any known complications during two years of infliximab treatment. When she presented there was no history of Crohn’s-associated oral ulcerations. No other significant medical history or allergies were noted.

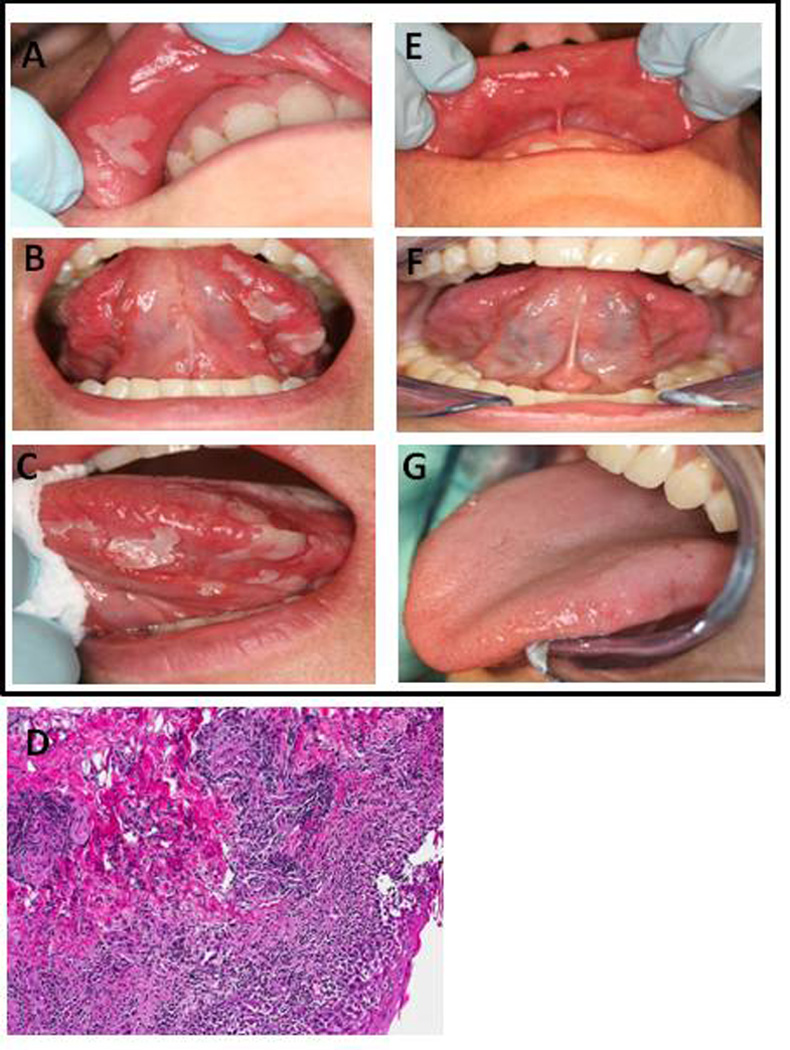

Oral ulcerations (Figs. 1A, 1B, 1C) developed after the second dental visit. The oral presentation included shallow ulcerations with an erythematous halo and pseudomembrane on the labial mucosa, and larger (1cm) ulcerations on the tongue. Nikolsky’s sign was negative. Furthermore, multiple cutaneous lesions were noted demonstrating small (less than one cm in diameter) erythematous papules on the hands, forearms, and plantar feet (Figs. 2A–E). Several of the papules had a central dusky appearance. The patient’s oral pain level was 7/10. She was afebrile and without signs or symptoms of upper or lower respiratory tract infection. The differential diagnosis included viral infection, EM, SJS, allergic reaction, erosive lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris and mucosal pemphigoid. The histopathological appearance (Fig. 1D) of the labial lesion revealed an acutely and chronically inflamed benign ulcer with marked spongiosis as well as intracellular edema with occasional necrotic keratinocytes. The histopathologic features were not consistent with diagnoses of oral CD, lichen planus, pemphigus, pemphigoid or malignancy. The cutaneous biopsy demonstrated necrotic keratinocytes and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate of the dermis without eosinophils, consistent with EM. Coxsackievirus A and B antibodies were negative/weakly positive, oral cultures and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative, and the patient did not respond to empiric treatment with oral acyclovir.

Figure 1.

Clinical oral presentation includes (A, B, C) shallow ulcerations with an erythematous halo and pseudomembrane on the labial mucosa, and larger (1 cm) ulcerations on the tongue. (D) H&E staining of the upper labial mucosa reveals prevalent lymphocytic infiltrate and necrotic keratinocytes. Labial biopsy section shown at 10× magnification. (E,F,G) Results post-treatment with dexamethasone (0.5 mg/5 ml) oral rinse.

Figure 2.

(A–E) Dermal presentation of the hands and forearm consisted of multiple small erythematous papules that had a central dusky appearance.

A diagnosis of EM major was made based upon the minimal cutaneous lesion presentation, the patient history, the temporal relation to infliximab infusions, the histopathologic evaluations, and a negative evaluation for active HSV disease. The patient's treatment consisted of dexamethasone rinse (0.5 mg/5 ml), 5 ml, swish and spit, every six hours for seven days. The oral lesions resolved in seven days without recurrence. (Fig. 1E, 1F, 1G) Skin lesions were treated concurrently with 40 mg prednisone, systemically for one week, with tapered doses in subsequent weeks. The patient’s skin lesions gradually resolved in 5 weeks. Taking into consideration the lack of present CD symptoms, the patient was not challenged with infliximab.

In subsequent 6 month and one year recalls, the patient never had another oral flare up. This seemingly can be attributed to the fact that the patient was taken off of infliximab and once again placed on a daily dose of 125 mg of Imuran (not accompanied with any corticosteroid) for management of the patient’s CD.

Discussion

There were several challenges in the diagnosis of this case. First, CD may manifest as oral lesions (oral CD). Typically, oral CD presents as indurated taglike lesions, described as deep linear ulcers with hyperplastic margins, labial, buccal or gingival swelling with induration and cobblestone or hyperplastic appearance of the buccal mucosa.9,10 EM is noted for its multiple ulcerations of the oral mucosal surfaces, often with prominent involvement of the lips. Multiple papules and vesicles are preceded by erythematous macules. The vesicles tend to rupture, leaving multiple areas of superficial erosions that are usually covered by a yellow fibrinous pseudomembrane.11–13

Another challenge in this case was to decide if the patient had EM or SJS, as both are reported to occur after anti-TNF-α therapy. In the past twenty years, a number of authors have reviewed the categorization of the diagnostic categories of EM major, SJS, and TENS and highlighted relatively new delineations and consensus regarding these terms.11, 14–17 EM major is highly variable with regard to its episodic frequency and the severity with oral mucosal lesions that occur in more than 70% of cases. Skin lesions, which may or may not be present, are characterized by atypical targetoid papules and plaques that are limited to less than 10% of the skin. There is a strong association with HSV or opportunistic infections including mycoplasma pneumoniae and candidiasis in over 70% of cases, with medications sometimes being implicated as well.11–16 Oral lesions are often painful but in general the oral lesions associated with EM are less severe than those of SJS. EM lesions heal without scarring, have a negative Nikolsky’s sign, and medical complications are rare.11, 14–16 EM’s histopathology tends to demonstrate inflammation with an abundance of lymphocytic infiltrate and necrotic keratinocytes.11, 14–17 Immunofluorescence was not utilized because the H & E biopsy was sufficient, given the history and clinical appearance. Furthermore, HSV or other microbial infections may elicit further EM episodes, and anti-viral suppression therapy may be necessary.11, 14–16

SJS also demonstrates variability. It usually occurs within 45 days after a drug exposure, and re-exposure to the same pharmacotherapy may result in secondary episodes with greater severity. A prodrome may occur 7 to 14 days before SJS lesions. There are a potential range of symptoms which include fever, headache, myalgia and nausea.11 The widespread cutaneous lesions of SJS are macular and may cover over 10% of the skin, including the face, neck, chin, and trunk. When such lesions cover greater than 30%, the diagnostic category becomes TENS. When target lesions occur, they are larger, and not as well demarcated compared with EM. Some, but not all, SJS lesions may elicit a positive Nikolsky’s sign. Several mucosal sites may be affected including the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, conjunctiva, and genitalia, sometimes with hemorrhagic tissue sloughing. In contrast to EM, SJS is strongly associated with a drug reaction.11, 14–16 With regard to histopathology in SJS, there is a predominant necrotic pattern, while with EM the predominant pattern is inflammatory with a lichenoid infiltrate and minimal necrosis of keratinocytes.11, 14–17 EM and SJS are generally treated with corticosteroids, topical and/or systemic, based upon the severity of symptoms.11, 15, 16

In the present case, it was noted that the cutaneous lesions tended to be papular rather than macular and covered less than 10% of the cutaneous surface area, the Nikolsky’s sign was negative, and the histopathologic appearance leaned more towards inflammation and less towards necrosis. Therefore, the consensus diagnosis of the presented case was EM major. Although, the immune-related reaction appeared to be drug-induced by infliximab, the clinical appearance, histopathology, and history supported the diagnosis of EM major rather than SJS.

Oral lesions associated with anti-TNF-α reactions have been reported previously. Ahdout et al., 2010,6 described a patient treated with adilimumab for psoriasis who met the diagnostic criteria for both EM major and SJS. At the time of the first dose of adilimumab, active HSV-2 was identified. Following the second dose of adalimumab, signs of both EM major and SJS developed. The patient described in this case report had histological features more consistent with EM. In addition, the targetoid morphology and acral distribution of skin lesion was consistent with EM.

Salama and Lawrance (2009)7 described a patient with cutaneous sloughing consistent with SJS, and oral mucositis and peripheral rash consistent with both SJS and EM after adalimumab therapy. Initially, adalimumab was discontinued, but was restarted following flares of perianal CD. After the second dose, severe oral mucositis and skin rash recurred, and the histopathologic diagnosis of the skin lesions noted a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Interestingly, the patient tolerated subsequent treatment with infliximab without recurrence of her symptoms. Both of these previously reported cases were managed successfully with systemic steroids and discontinuation of the offending drug.

This case emphasizes the need of the dental professional to be cognizant of the complications of anti-TNF-α agents. The leading anti-TNF-α medications, infliximab (Remicade), etanercept (Enbrel) and adalimumab (Humira) all have documented adverse and serious cutaneous reactions associated with their use. Numerous reports also have identified paradoxical specific induction of cutaneous-based reactions including dermatitis, psoriasis,18 Henoch-Schönlein purpura,19 SJS,7 and EM.20

In summary, patients concurrently taking anti-TNF-α agents presenting with vesiculoerosive/vesiculobullous oral lesions should be referred to the clinician-prescriber of the anti-TNF-α agent for a complete evaluation, which may include discontinuation of the anti-TNF-α agent if causative. It is recommended that contributory oral lesions receive glucocorticoid treatment to achieve efficacious healing. Consultation with the patient’s primary physician is suggested, since many patients taking this class of biological agents will have an underlying inflammatory disease and additional co-morbidities. It can be expected that physicians will discontinue the use anti-TNF-α agent, as occurred in our case report.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement statement; This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDCR/NIH. We wish to thank Dr. Jane Atkinson for her supervision and help with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kvien TK, Heiberg LE, Kaufmann C, Mikkelsen K, Nordvag BY, Rodevand E. A Norwegian DMARD register: prescriptions of DMARDs and biological agents to patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S188–S194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun J, Deodhar A, Kijkmans B, Geusens P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over a two-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1270–1278. doi: 10.1002/art.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidder HF, Schnitzier F, Ferrante M, Norman M, et al. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:501–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zabana YE, Domenech E, Manosa M, Garcia-Planella E, et al. Infliximab safety profile and long-term applicability in inflammatory bowel disease: 9-year experience in clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, et al. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease: the Mayo clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 126(1):19–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahdout J, Haley JC, Chiu MW. Erythema multiforme during anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:874–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salama M, Lawrance IC. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:444–452. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDA Drug Safety Newsletter. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. [Date access 2/23/12];2008 Winter;Volume 1(Number 2) Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drugsafety/drugsafetynewsletter/ucm109165.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupuy A, Cosnes J, Revuz J, Delchier JC, Gendre JP, Cosnes A. Oral Crohn disease: clinical characteristics and long-term follow-up of 9 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:439–442. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn's disease. An analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 13:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams PM, Conklin RJ. Erythema multiforme: a review and contrast from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dent Clin North Am. 49:67–76. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lozada-Nur F, Gorsky M, Silverman S., Jr Oral erythema multiforme: Clinical observations and treatment of 95 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:36–40. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown RS, Farquharson AA, Morton I, Tyler MT. Oral Erythema Multiforme major: a triple case report. Gen Dent. 2011;59:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayangco L, Rogers RS., 3rd Oral manifestations of erythema multiforme. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assier H, Bastuji-Garin S, Revuz J, Roujeau JC. Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are clinically different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cote B, Wechsler J, Bastuji-Garin S, Assier H, Revuz J, Roujeau JC. Clinicopathologic correlation in erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1268–1272. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690230046008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau J-C. Clinical Classification of Cases of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Erythema Multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma N, Lindsay J. Anti-TNF-Alpha-Induced Psoriasis-An Unusual Paradox. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:404–407. doi: 10.1159/000257907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman FZ, Takhar GK, Roy O, Sherpherd A, Bloom SL, McCartney SA. Henoch-Schonlein purpura complicating adalimumab therapy for Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2010;1:119–122. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v1.i5.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sciaudone G, Pellino G, Guadagni I, Selvaggi F. Education and imaging: gastrointestinal: herpes simplex virus-associated erythema multiforme (HAEM) during infliximab treatment for ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:610. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]