Abstract

Objective

Up to 50% of burn patient fatalities have a history of alcohol use, and for those surviving to hospitalization, alcohol intoxication may increase the risk of infection and mortality. Yet, the effect of binge drinking on burn patients specifically with inhalation injuries is not well described. We aimed to investigate the epidemiology and outcomes of this select patient population.

Methods

In a prospective study, 53 patients with an inhalation injury and a documented blood alcohol content (BAC) were grouped as: BAC negative (n=37), BAC 1–79 mg/dL (n=4), and BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL (n=12). Those in the latter group were designated as binge drinkers according to National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism criteria.

Results

Binge drinkers with an inhalation injury had considerably smaller % total body surface area (TBSA) burns than did their non-drinking counterparts (mean % TBSA 10.6 vs 24.9; p = 0.065), and significantly lower revised Baux scores (mean 75.9 vs 94.9; p = 0.030). Despite binge-drinkers having smaller injuries, the groups did not differ in terms of outcomes and resource utilization. Finally, those in the binge-drinking group had considerably higher carboxyhemoglobin levels (median 5.2 vs 23.0; p=0.026) than did non-drinkers.

Conclusions

Binge drinkers with inhalation injuries surviving to hospitalization had less severe injuries than did non-drinkers, though their outcomes and burden to the health care infrastructure were similar to the non-drinking patients. Our findings affirm the impact of alcohol intoxication at the time of burn and smoke inhalation injury, placing renewed emphasis on injury prevention and alcohol abuse education.

Keywords: Alcohol, Burn, Smoke Inhalation

Introduction

In the United States, alcohol is the third leading lifestyle-related cause of mortality,1,2 and the years of potential life lost are measured in the millions.1 Without question the risks associated with alcohol play a prominent role in burn care, in that up to 50% who die from burn injury are intoxicated.3,4 Furthermore, alcohol use at the time of burn injury increases susceptibility to bacterial infection, suppresses cellular immunity,5 and is a risk factor for hospital mortality.6 Of concern is that recent reports indicate an upward trend of alcohol misuse in burn and inhalation injury.7–9 Nonetheless, alcohol use (particularly binge drinking) and its relation to inhalation injury remains poorly described. Therefore, we aimed to better characterize the epidemiologic and clinical implications of binge drinking in those with inhalation injuries.

Methods

Patients and Parameters

In a prospective study from January 2007 to May 2011, bronchoscopy was performed on 82 burn patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) when smoke inhalation injury was suspected by history, physical, and/or laboratory findings. Patients were excluded for the following: age less than 18 years, malignancy, use of immunosuppressive medications, or known autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases. Of these, 7 were excluded for declining study participation, and 22 were excluded for either having not had an inhalation injury or having no blood alcohol content (BAC) measured within 4 hours of hospital presentation. The final cohort of 53 patients were grouped as BAC negative (n=37), BAC 1–79 mg/dL (n=4), and BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL (n=12). Patients with a BAC ≥ 80 were designated as binge drinkers according to National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) criteria,10 and are referred to as such throughout the manuscript. Clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and outcomes were compared between groups. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Variables

The following variables were collected and determined prospectively: age, gender, race/ethnicity, presenting carboxyhemoglobin (% COHb) level, BAC (mg/dL), results of urine toxicity screen, % total body surface area (TBSA) burn, presence of inhalation injury, inhalation injury grade (1–4, with grade 4 being the worst severity of injury according to the bronchoscopic examination as described by Endorf and Gamelli),11 revised Baux Score [Age + % TBSA + 17*(Inhalation Injury, 1=Yes, 0=No)],12 pneumonia, sepsis, tracheostomy, ICU and hospital length of stay, and mortality. Pneumonia and sepsis were defined according to American Burn Association Consensus Conference criteria.13 Otherwise mechanism of injury, insurance status, transfusion requirements, days of antibiotics/antifungals, disposition, and total hospital charges were obtained retrospectively after patient discharge.

Statistical analysis

Data were assessed for normality and parametric or non-parametric tests applied where appropriate. Specifically, parametric data were analyzed by the Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (with Bonferroni’s post-test), and non-parametric data were analyzed by the Mann Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test (with Dunn’s post test). Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean with standard deviation, and non-parametric data are reported as median with 25th and 75th percentiles. Otherwise dichotomous variables were compared with Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, and are reported as a number and percent. Logistic regression was performed, where indicated, to adjust for the effects of relevant confounders. Statistical analyses were calculated with SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and corresponding graphs created with GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A difference between observed variables was considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

The overall frequency of burn patients admitted with both inhalation injuries and a positive BAC was 30%, whereas the frequency of binge drinking was 26 %. Table 1 represents these patients’ demographics classified by BAC. The groups did not differ in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, mechanism of injury, or insurance status. Compared to non-drinkers, binge drinking patients were more frequently male, more commonly injured at home, and less frequently Hispanic, though these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Demographics comparing patients with smoke inhalation injuries by presenting blood alcohol content (BAC)

| BAC negative n=37 | BAC 1–79 mg/dL n=4 | BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL n=12 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55 (35–72) | 51 (43–56) | 49 (27–57) | 0.712 |

| Gender | 0.125 | |||

| Male | 20 (54) | 4 (100) | 9 (75) | |

| Female | 17 (46) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.293 | |||

| White | 21 (57) | 1 (25) | 7 (58) | |

| Black | 10 (27) | 2 (50) | 4 (33) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (14) | 0 | 0 | |

| Asian | 1 (3) | 1 (25) | 1 (8) | |

| Mechanism of Injury | 0.653 | |||

| House Fire | 30 (81) | 3 (75) | 12 (100) | |

| Vehicle | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| Employment | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| Assault | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Suicide | 1 (3) | 1 (25) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Insurance | 0.543 | |||

| Private | 5 (14) | 0 | 2 (17) | |

| Medicare | 13 (35) | 0 | 5 (42) | |

| Medicaid | 5 (14) | 1 (25) | 3 (25) | |

| Uninsured | 12 (32) | 3 (75) | 2 (17) | |

| Workers Compensation | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 |

Data represented as n (%) or median and interquartile ranges (25th-75th)

Clinical Comparisons

Comparisons of the clinical features of inhalation-injured burn patients according to BAC are demonstrated in Table 2. The median BAC for binge drinkers was 212 mg/dL. Patients who were drinking at the time of burn and smoke inhalation injury more frequently tested positive for illicit substances than did non-drinkers (opiates and benzodiazepine were not included given the routine use of these for sedation and analgesia).

Table 2.

Clinical considerations comparing patients with smoke inhalation injuries by presenting blood alcohol content (BAC)

| BAC negative n=37 | BAC 1–79 mg/dL n=4 | BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL n=12 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAC (mg/dL) | 0 | 33 (11–61) | 212 (130–247) | N/A |

| Concurrent illicit drugs* | 7 (23) | 3 (100) | 4 (36) | 0.031 |

| % TBSA | 17.0 (1.3–41.0) | 3.5 (1.3–71.0) | 3.5 (0.3–18.5) | 0.218 |

| Inhalation injury grade | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.559 |

| Revised Baux Score | 99.0 (78.3–110.0) | 76.0 (67.8–133.0) | 76.0 (61.3–91.5)† | 0.069 |

| COHb (%) | 5.2 (2.0–10.9) | 4.4 (2.9–8.6) | 23.0 (7.5–27.4)‡ | 0.026 |

Data represented as n (%) and median and interquartile ranges (25th-75th)

COHb, carboxyhemoglobin; Revised Baux, Age + % TBSA + 17*Inhalation Injury (0=No, 1=Yes); % TBSA, total body surface area skin burn

p<0.05 vs BAC negative, Mann Whitney test

p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test, post-hoc analysis

of those who had available data

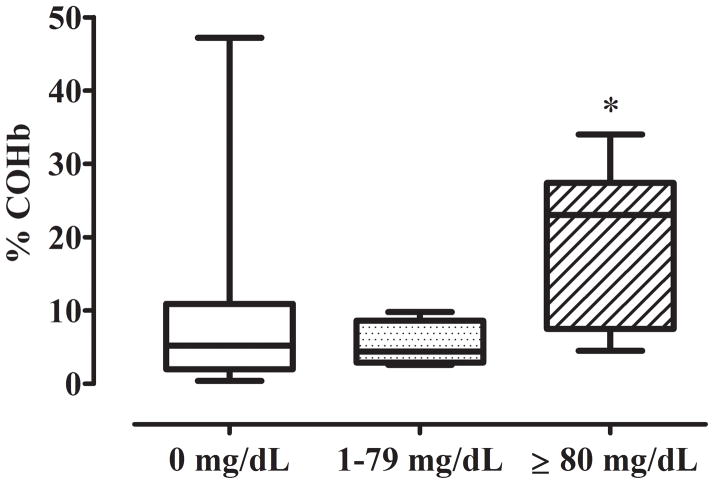

Surprisingly, binge drinking patients had much smaller % TBSA burns when compared directly against their non-drinking counterparts (median 3.5 versus 17.0, respectively; p=0.08), as well as significantly lower revised Baux scores (median 76.0 versus 99.0, respectively; p=0.02). The difference in % TBSA between binge-drinkers and non-drinkers was similar even if comparing the mean burn size (mean 10.6 versus 24.9; p=0.065), as was the difference in revised Baux scores (mean 75.9 versus 94.9; p=0.03). On the contrary, the grade of inhalation injury did not differ between groups. Despite a lower overall injury acuity, the % COHb varied widely between the groups. When compared to non-drinkers, the median % COHb of binge drinkers was over four times as high (median 23.0 versus 5.2; p=0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

% COHb in burn-injured patients with inhalation injuries, by blood alcohol content. *p<0.05, versus 0 mg/dL. Kruskal-Wallace test, post-hoc analysis.

Outcomes and resource utilization

Despite binge drinking patients having much smaller burn injuries, their outcomes and resource utilization were similar to non-drinkers (Table 3). First, the occurrence of sepsis and pneumonia did not differ between binge drinkers and non-drinkers. Likewise, the frequency and amount of blood transfusions, number of days on systemic antimicrobials, and number of days on the ventilator, in the ICU, and in the hospital were similar between binge drinkers and non-drinkers. The overall cost of hospitalization for these patients was impressive, and even for binge drinkers with relatively mild injuries was typically in the range of $200,000.

Table 3.

Outcomes comparing patients with smoke inhalation injuries by presenting blood alcohol content (BAC)

| BAC negative n=37 | BAC 1–79 mg/dL n=4 | BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL n=12 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septic | 10 (27) | 0 | 2 (17) | 0.647 |

| Pneumonia | 22 (59) | 1 (25) | 6 (50) | 0.390 |

| Transfusions | ||||

| Yes | 22 (59) | 0 | 6 (50) | 0.095 |

| Units PRBCs | 1 (0–6) | 0 | 1 (0–3) | 0.095 |

| Antibiotic Days | 10 (2–26) | 0 (0–12) | 13 (3–20) | 0.174 |

| Antifungal Days | 11 (0–31) | 0 (0–16) | 14 (2–23) | 0.355 |

| Tracheostomy | 16 (43) | 1 (25) | 5 (42) | 0.904 |

| Ventilator Days | 14 (6–35) | 5 (2–24) | 19 (7–35) | 0.276 |

| ICU Days | 23 (9–42) | 7 (7–30) | 23 (10–35) | 0.457 |

| Hospital LOS | 26 (10–46) | 8 (7–32) | 24 (13–35) | 0.429 |

| Hospital charges | 221,282 (77,002–393,443) | 74,920 (37,073–242,686) | 201,137 (97,439–380,244) | 0.381 |

| Disposition | 0.119 | |||

| Home/Home Health | 10 (27) | 3 (75) | 2 (17) | |

| Rehabilitation | 2 (19) | 0 | 5 (42) | |

| Nursing Home/SNF | 4 (11) | 0 | 5 (3) | |

| LTAC | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (8) | |

| Deceased | 12 (32) | 1 (25) | 0 | |

| Other | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (8) | |

Data represented as n (%) or median and interquartile ranges (25th-75th)

ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; LTAC, long-term acute care; PRBCs, packed red blood cells; SNF, skilled nursing facility

Finally, the overall disposition of non-drinking and binge-drinking burn patients hospitalized with inhalation injuries was similar, again despite much lower injury severities in the binge-drinking group. The rates of mortality in the BAC group, the BAC 1–79 mg/dL group, and the binge-drinking group were 32%, 25%, and 0%, respectively, though these differences were not significant on multivariate analysis.

Discussion

From the perspective of binge drinking in this select population of burn-injured patients with concomitant inhalation injuries, our primary findings are threefold. First, the prevalence of alcohol use at the time of injury (30%) was consistent with the literature. Second, % COHb in binge drinking patients with inhalation injuries was much higher than their non-drinking counterparts. And third, despite a considerably lower % TBSA and revised Baux score, the binge drinking group had similar resource utilization compared to the non-drinking group.

The prevalence of alcohol dependence in those injured or killed by burns may be as high as 40–60%.3,4,14 Similarly high frequencies of acute intoxication in burn patient fatalities have also been described.15,16 For instance, in a metaanalysis involving 1,677 burn-related deaths, Smith et al found that approximately 40% were intoxicated at the time of injury (as defined by a BAC ≥ 100 mg/dL).15 Of those surviving to hospitalization, the frequency of those with alcohol use disorders is equally impressive, in that over 20% may meet criteria for at-risk drinking.17 Recent data from the United Kingdom (some specific to those with inhalation injuries) indicate that the frequency of alcohol abuse in this population is not only very high, but that it is also increasingly common.7,9 The results of our study are in-line with both recent and historical data, as we identified that 26% of inhalation-injured burn patients admitted to the ICU had a BAC ≥ 80 mg/dL; undoubtedly, excessive consumption of alcohol in this patient population is considerable and may be the primary risk factor for their high % COHb levels in that they may have been unable to detect the smoke or fire, or may have been unable to safely remove themselves from their environment.

Unexpectedly, there were no deaths among inhalation-injured patients in the binge-drinking group. This is particularly surprising given that many, if not the majority, of burn fatalities involve inhalation injury, carbon monoxide (CO) exposure, and/or alcohol toxicity.18–20 In fact, alcohol consumption at the time of burn injury has almost ubiquitously been associated with an increased risk of mortality,6,16,18–22 other than the rare study that finds either no correlation23–25 or a seemingly protective effect.26 We explain our findings in that the % TBSA was much lower in the binge group and hence the difference in mortality was not significant after adjusting for the effects of age and % TBSA. Moreover, we cannot account for fatalities either at the scene or in transit to our institution. We do not believe that our data suggest a protective effect of binge drinking against mortality in inhalation-injured patients. A much larger sample size is required to investigate these effects, especially for matched comparisons, and future studies should include data from the field for comparison.

The direct association between % COHb levels and alcohol use at the time of burn injury is rarely reported, and oftentimes such a correlation can only be inferred. However, there are studies such as that by Yeoh and Braitberg that do note a positive correlation between BAC and % COHb.27 Other reports have either not made a direct comparison or have not found such an association. For example, in a study of 286 fire-related deaths, Rogde et al found no influence on % COHb by BAC.28 Though the effects of CO toxicity vary considerably in burn patients, high circulating levels of CO can result in death, permanent neurologic impoverishment, delayed neurologic recovery, and may negatively impact cardiopulmonary physiology in the way of ischemia, pulmonary arterial shunting, and pulmonary edema.29,30 Moreover, it is plausible that tissue hypoxia as the result of CO toxicity could exacerbate the local pro-inflammatory effects in the lung previously documented with the combination of alcohol and burns.31 Further investigations into the biological effects of CO in these patients are thus warranted.

This study underscores the public health implications of alcohol misuse in a well-defined patient population. Indeed, the median BAC of binge drinkers in this study was 212 mg/dL, and the higher % COHb levels in these patients is likely reflective of significant impairment of self-extrication.32 Moreover, binge drinkers had similar resource consumption as did non-drinkers who had considerably worse burns, with both groups having similar hospital charges, antimicrobial use, transfusion requirements, and post-hospitalization dispositions requiring home health, rehabilitation/nursing facilities, and/or long-term acute care. Finally, the negative impact of alcohol use at the time of burn injury on subsequent outcomes, such as infectious complications and length of stay, is well-described.6,7,16,21–23,25,26,33,34 Our findings thus place a renewed emphasis on the importance of alcohol abuse education and injury prevention programs, and suggest that the binge-drinking victim of burn and inhalation injury should be managed according to their specific presentation.

We also speculate that alcohol intoxication at the time of burn and smoke inhalation alters the biological response to injury and negatively impacts outcomes, particularly when combined with the effects of CO toxicity and alcohol withdrawal among chronic alcohol users. Although our methods do not allow us to differentiate chronic heavy drinkers from episodic binge drinkers in this study, the fact that even acute alcohol intoxication can alter the biological response to injury is an important consideration. Indeed, this factor can subsequently enhance the risk for infections and impair wound healing, which are both essential determinants of outcome in these patients.5,35–39 Additionally, it is already known that alcohol intoxication at the time of burn injury increases fluid resuscitation requirements,23 which we should continue to recognize while managing these patients. However, an under-recognized dynamic is that not all binge drinkers are chronic users of alcohol. Not all binge drinkers will be at risk for alcohol withdrawal, and assessing burn patients with inhalation injuries for patterns of chronic alcohol abuse is difficult since they often remain intubated through the period when alcohol withdrawal will typically begin. In our unit, we thus observe the potential need for enhanced resuscitation requirements and expectantly manage alcohol withdrawal as it occurs. Although the data are not available in the present study, we currently employ the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) protocol in our burn intensive care unit in order to detect and manage alcohol withdrawal. Until we have a better understanding of how isolated acute alcohol exposure alters the biological response to injury in humans, our recommendation is to recognize that even binge drinkers with seemingly minor injuries may behave like individuals who are more severely injured.

We acknowledge a few limitations. First, without data from fatalities (either at the scene or at referring hospitals), the generalizability of our data is restricted. Second, we did not routinely assess all patients for chronic alcohol abuse nor did we determine if patients developed the alcohol withdrawal syndrome; thus, we cannot determine if the binge drinkers in this study have acute alcohol exposure in addition to chronic drinking or if they episodically binge drink. Nevertheless, it is clear that a high BAC is a good reflection of alcohol use at the time of inhalation injury. Last, though our sample size was moderate, a larger cohort will be required in the future to determine if binge-drinking is indeed an independent predictor of poor outcomes in burn patients with inhalation injuries.

Conclusion

The prevalence of binge drinking in burn patients with inhalation injuries is high. These patients are at increased risk for CO intoxication, and their consumption of health care resources is high. However, the biological effects of alcohol intoxication at the time of burn and inhalation injury remain to be elucidated in humans. These points are deserving of further investigative and intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the National Institutes of Health [T32 AA013527 (EJK), R01 AA012034 (EJK), R01 AA015067 (TJE), P30 AA01937 (EJK)], the Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-1-0619), and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (EJK)

This work could not have been accomplished without the nursing and support staff in the Burn ICU at Loyola University Hospital.

Footnotes

Accepted for poster presentation during the 44th Annual Meeting of the American Burn Association, April 24-27, Seattle, Washington.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost--United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(37):866–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howland J, Hingson R. Alcohol as a risk factor for injuries or death due to fires and burns: review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 1987;102(5):475–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingson R, Howland J. Alcohol and non-traffic unintended injuries. Addiction. 1993;88(7):877–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on cellular immune responses in a murine model of thermal injury. J Leukoc Biol. 1997 Dec;62(6):733–40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, et al. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J Trauma. 1995;38(6):931–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes WJ, Hold P, James MI. The increasing trend in alcohol-related burns: it’s impact on a tertiary burn centre. Burns. 2010;36(6):938–43. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam N, Hussain MA. Comments on “the increasing trend in alcohol-related burns: it’s impact on a Tertiary burn centre”. Burns. 2011 May;37(3):542–3. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.10.012. author reply 543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett SP, Trickett RW, Potokar TS. Inhalation injury associated with smoking, alcohol and drug abuse: an increasing problem. Burns. 2009;35(6):882–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. [Accessed March 31, 2008];NIAAA Newsletter. 2004 (3):3. Available at http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf.

- 11.Endorf FW, Gamelli RL. Inhalation injury, pulmonary perturbations, and fluid resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(1):80–3. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802C889F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osler T, Glance LG, Hosmer DW. Simplified estimates of the probability of death after burn injuries: extending and updating the baux score. J Trauma. 2010;68(3):690–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c453b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Holmes JHt, et al. American Burn Association consensus conference to define sepsis and infection in burns. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(6):776–790. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181599bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steenkamp WC, Botha NJ, Van der Merwe AE. The prevalence of alcohol dependence in burned adult patients. Burns. 1994;20(6):522–5. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR. Fatal nontraffic injuries involving alcohol: A metaanalysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):659–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones JD, Barber B, Engrav L, Heimbach D. Alcohol use and burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1991;12(2):148–52. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albright JM, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL, Schermer CR. Implications of formal alcohol screening in burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(1):62–9. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181921f31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine MS, Radford EP. Fire victims: medical outcomes and demographic characteristics. Am J Public Health. 1977;67(11):1077–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.11.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patetta MJ, Cole TB. A population-based descriptive study of housefire deaths in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(9):1116–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.9.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristinsson J, Johannesson T, Bjarnason O. The role of carbon monoxide and ethanol in fire casualties: A retrospective study of carboxyhemoglobin and blood ethanol levels in fire victims. Laeknabladid. 1994;80(5):185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, et al. The effects of preexisting medical comorbidities on mortality and length of hospital stay in acute burn injury: evidence from a national sample of 31,338 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245(4):629–34. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250422.36168.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haum A, Perbix W, Häck HJ, et al. Alcohol and drug abuse in burn injuries. Burns. 1995;21(3):194–9. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)80008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silver GM, Albright JM, Schermer CR, et al. Adverse clinical outcomes associated with elevated blood alcohol levels at the time of burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(5):784–9. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818481bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thal ER, Bost RO, Anderson RJ. Effects of alcohol and other drugs on traumatized patients. Arch Surg. 1985;120(6):708–12. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390300058010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brezel BS, Kassenbrock JM, Stein JM. Burns in substance abusers and in neurologically and mentally impaired patients. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9(2):169–71. doi: 10.1097/00004630-198803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grobmyer SR, Maniscalco SP, Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Alcohol, drug intoxication, or both at the time of burn injury as a predictor of complications and mortality in hospitalized patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17(6 Pt 1):532–9. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeoh MJ, Braitberg G. Carbon monoxide and cyanide poisoning in fire related deaths in Victoria, Australia. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(6):855–63. doi: 10.1081/clt-200035211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogde S, Olving JH. Characteristics of fire victims in different sorts of fires. Forensic Sci Int. 1996;77(1–2):93–9. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(95)01844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grieb G, Simons D, Schmitz L, et al. Glasgow Coma Scale and laboratory markers are superior to COHb in predicting CO intoxication severity. Burns. 2011;37(4):610–5. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange M, Cox RA, Enkhbaatar P, et al. Predictive role of arterial carboxyhemoglobin concentrations in ovine burn and smoke inhalation-induced lung injury. Exp Lung Res. 2011;37(4):239–45. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2010.538133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel PJ, Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Duffner LA, Kovacs EJ. Elevation in pulmonary neutrophils and prolonged production of pulmonary macrophage inflammatory protein-2 after burn injury with prior alcohol exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999 Jun;20(6):1229–37. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barillo DJ, Rush BF, Jr, Goode R, et al. Is ethanol the unknown toxin in smoke inhalation injury? Am Surg. 1986;52(12):641–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powers PS, Stevens B, Arias F, et al. Alcohol disorders among patients with burns: crisis and opportunity. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1994;15(4):386–91. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199407000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelley D, Lynch JB. Burns in alcohol and drug users result in longer treatment times with more complications. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1992;13(2 Pt 1):218–20. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung MK, Callaci JJ, Lauing KL, et al. Alcohol exposure and mechanisms of tissue injury and repair. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(3):392–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karavitis J, Murdoch EL, Gomez CR, et al. Acute ethanol exposure attenuates pattern recognition receptor activated macrophage functions. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28(7):413–22. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radek KA, Kovacs EJ, DiPietro LA. Matrix proteolytic activity during wound healing: modulation by acute ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(6):1045–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radek KA, Matthies AM, Burns AL, et al. Acute ethanol exposure impairs angiogenesis and the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(3):H1084–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00080.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Messingham KA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol, injury, and cellular immunity. Alcohol. 2002;28(3):137–49. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]