Abstract

Cells face the challenge of storing two meters of DNA in the three-dimensional (3D) space of the nucleus that spans only a few microns. The nuclear organization that is required to overcome this challenge must allow for the accessibility of the gene regulatory machinery to the DNA and, in the case of embryonic stem cells (ESCs), for the transcriptional and epigenetic changes that accompany differentiation. Recent technological advances have allowed for the mapping of genome organization at an unprecedented resolution and scale. These breakthroughs have lead to a deluge of new data, and a sophisticated understanding of the relationship between gene regulation and 3D genome organization is beginning to form. In this review we summarize some of the recent findings illuminating the 3D structure of the eukaryotic genome, as well as the relationship between genome topology and function from the level of whole chromosomes to enhancer-promoter loops with a focus on features affecting genome organization in ESCs and changes in nuclear organization during differentiation.

Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), isolated from the inner cell mass of pre-implantation blastocysts, self-renew indefinitely under appropriate culture conditions and have the ability to produce cell types from all three germ layers upon induction of differentiation in vivo and in vitro 1,2. Linear genomic features, such as the location of transcription factors, the basic transcriptional machinery, and chromatin modifications, as well as DNase hypersensitivity, expression state, and replication timing have been extensively mapped in ESCs. Therefore, gene regulatory processes controlling the transcriptional program of ESCs are relatively well characterized (reviewed recently elsewhere3) and center on three core transcriptional networks: the pluripotency network, made up of highly expressed, ESC-specific genes bound by the transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog which, together, control pluripotency through co-binding of many enhancers and promoters including their own3; the cMyc network, formed by transcription factors of the Myc family which drives gene expression by promoting the release of paused polymerase at its target genes4; and, the Polycomb group (PcG) protein network, which represses developmental and lineage specific genes5 through the tri-methylation of lysine 27 of histone 3 (H3K27me3)6, H2AK119 ubiquitylation7, and chromatin compaction8. These transcriptional networks work in concert with external signaling pathways to maintain the pluripotent state, most notably the LIF-Jak-Stat pathway in mouse ESCs9 and bFGF-signaling in human ESCs10. Highlighting the importance of these transcriptional networks to pluripotent cell identity, ectopic expression of Oct4, Sox2, cMyc, and the pluripotency-associated transcription factor Klf4 is sufficient to reprogram somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)11. iPSCs carry all the typical characteristics of ESCs including self-renewal, expression of the endogenous pluripotency program, and differentiation in both the teratoma and chimera formation assays11. More recently, there has been a push towards determining genome organization and correlating 3D topology with genomic functions such as transcriptional regulation. Because transcriptional networks and gene regulation are well studied in ESCs, these cells are a great model system with which to understand 3D genome organization and its changes upon cell fate change. In this review, we will first summarize general aspects of genome organization revealed from work with various cell types and then focus on new findings that begin to address genome organization in ESCs and changes upon induction of differentiation.

Widely conserved features of genome organization: A top down view

Years of research from many groups utilizing a variety of cell types from numerous species have defined a number of general features of eukaryotic genome organization. Interphase chromosomes reside in discrete, minimally overlapping chromosome territories (CTs, reviewed exhaustively by the Cremer brothers12, Figure 1a). CTs are organized such that small, gene rich chromosomes tend to pair and localize to the nuclear interior13,14. Cell type-specific radial positioning of CTs within the nucleus has also been reported15, although the extent to which CT pairing and positioning are conserved through mitosis varies depending on the cell type analyzed16,17. Individual genes are largely confined to their respective chromosome’s territory, however, in certain developmental contexts, such as Hox gene activation18 and X-chromosome inactivation19 (discussed in more detail below), gene loci have been shown to loop out or move to the outer edges of their CTs.

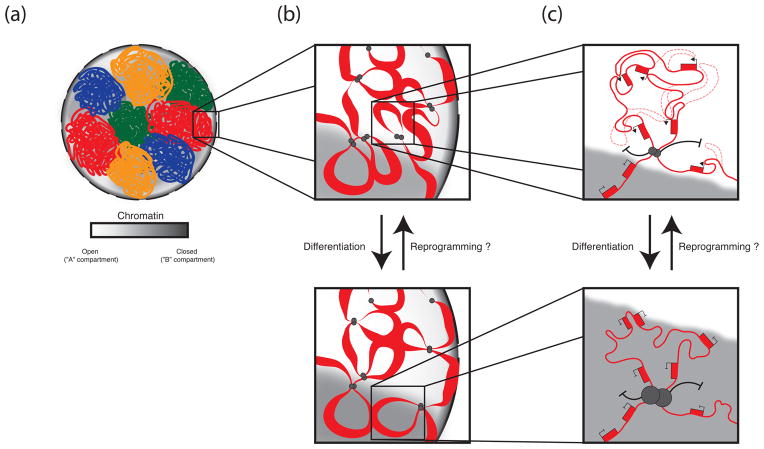

Figure 1. Hierarchical levels of genome organization and changes upon ESC differentiation.

Model of the 3D organization of the genome in ESCs and its changes during the course of differentiation. We infer this model by combining findings from many different cell types. (a) Chromosomes exist as discrete, minimally overlapping territories. At the megabase level, compartments of open (white) and closed (gray) chromatin coarsely divide the genome into regions enriched for features of euchromatin and those depleted of euchromatic features, respectively. Locus positioning within the open or closed compartment defines likely interaction partners, with loci in the open compartment interacting more frequently with other open loci, and those in closed more frequently with other closed loci. (b) Below the megabase, level the genome is divided into topological domains, which, we speculate, exist as large chromatin loops created by the juxtaposition of CTCF binding sites at TAD boundaries. These TADs function as modular units of genome organization whose member genes are often co-regulated, and we propose, localize as units within the nucleus and potentially switch between open and closed compartments during differentiation, somatic cell reprograming, or between different cell types as their euchromatic character changes. (c) Within TADs, enhancers and promoters loop together extensively and promiscuously to orchestrate cell type-specific gene expression profiles. Genes appear to be more likely co-regulated if they lie within the same TAD, as opposed to between TADs. During differentiation and transcription factor induced reprogramming, all genes within a TAD may switch their transcriptional state.

Localization of genomic regions to the nuclear periphery, specifically the nuclear lamina, is correlated with gene silencing across the eukaryotic kingdom20–22, and ectopic targeting of genetic loci to the nuclear envelope (NE) can induce transcriptional silencing in some cases20,23,24. NE-mediated gene silencing is thought to function in part through the interaction of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) with repressive protein complexes localized to the NE through interactions with the B-type lamins, the major constituents of the NE (reviewed extensively elsewhere25), as well as through histone-Lamin A interactions26. Sequestration of the transcriptional machinery away from the nuclear periphery has been suggested as an additional mechanism of NE-mediated transcriptional silencing, although it is unclear if this phenomenon is a general feature of eukaryotic genome organization27. Recent work has added a new player in targeting specific genomic regions to the NE, the vertebrate homologue of the Drosophila GAGA factor, cKrox. cKrox binds GA repeat-enriched lamina associating DNA sequences (LASs) in a cell type- specific manner, targeting these regions to the NE, although it is currently unclear how cKrox is targeted to specific LASs28.

Early studies of genome organization relied on cytological methods such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and as such were limited in the number of gene loci that could be analyzed in a single experiment. The past decade has witnessed the introduction of molecular techniques and high-throughput mapping to the field of genome organization in the form of chromosome conformation capture (3C)-based techniques. 3C allows for a molecular view of genome organization via chemical fixation, restriction enzyme digestion, ligation of juxtaposed DNA fragments and detection of ligation events by PCR. The juxtaposition frequency of two DNA fragments in 3D space can be inferred based on the quantity of the PCR product produced upon amplifying a given ligation event29. In recent years a number of groups have expanded 3C-based molecular techniques30 to include 4C – which allows for the identification of all chromatin contacts made by a single locus with the rest of the genome31,32, 5C – enabling the identification of all pair-wise chromatin interactions for a given genomic region33, Hi-C34 and its technical variants35–37 – permitting the identification of all pairwise chromatin interactions genome-wide, and ChIA-PET38 – allowing the identification of all pairwise chromatin interactions genome-wide, which share binding of a protein of interest.

These techniques have revealed a previously unappreciated hierarchical organization of eukaryotic genomes. As expected from the CT-based structure of the genome, intra-chromosomal (cis) chromatin interactions mapped by 3C-based techniques are much more frequent than inter-chromosomal (trans) ones31,34. Apart from verifying the existence of chromosome territories and the preferential pairing of small, gene rich chromosomes, mapping of genome-wide chromatin interactions with Hi-C in human lymphoblasts34, mouse pro-B cells39, and Drosophila embryos37 demonstrated the existence of a further organizational sub-division of the genome into ‘A’ and ‘B’ compartments, where the A compartment is enriched for features of euchromatin and the B compartment is depleted of these features34. From an organizational standpoint, chromatin interactions within compartments are much more frequent than those between compartments (Figure 1b).

The comparatively smaller size of the Drosophila genome allowed for higher resolution DNA topology mapping than was previously accomplished in mammalian genomes and led to the identification of a further organizational sub-division of the genome into linear domains with shared epigenetic features, ranging in size from 10 kilobases (kb) to 500kb37. These domains appear to act modularly in governing global genome organization in Drosophila. Interactions of loci within a given domain are more frequent than interactions between loci in different domains. However, where inter-domain interactions occur, active domains preferentially interact with other active, domains, inactive with inactive, and PcG-regulated with other domains of PcG enrichment37. Recent work with a number of different cell lines has identified analogous domains in mammalian genomes40–42, termed topological domains or topologically associating domains (TADs). TADs delimit the range within which enhancers can affect their target genes, as co-regulated enhancer-promoter groups tend to form extended clusters of interacting chromatin that align with TADs43 (Figure 1c). Additionally, the changes in gene expression upon differentiation are more likely to occur in the same direction for genes within a TAD than for genes in different TADs41. It has long been appreciated that enhancer-promoter interactions are responsible for regulating the cell type-specific expression of genes. The importance of looping between promoter and enhancers for gene regulation is highlighted by data from the ENCODE consortium showing that genes whose transcriptional start sites are contacted by an enhancer are more highly transcribed than those that are not44.

The locations of TAD boundaries are strongly conserved between the mouse and human genomes, particularly within syntenic regions; and TADs of both species’ are largely conserved across different cell types40,41. CP190, a critical contributor to the function of various Drosophila insulator proteins through its mediation of DNA looping45, is enriched at TAD boundaries in Drosophila, and the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF46 is similarly enriched at the boundaries of a large subset of mammalian TADs40,42, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of TAD formation by insulator proteins, similar to what has been proposed for mammalian insulators in general47. In ESCs, CTCF has been shown to mediate DNA looping events which partition the genome into physical domains each characterized by distinct epigenetic states42, supporting a model of DNA organization wherein many TADs function as large, independently regulated DNA loops (Figure 1b,c). Although the data arguing for the role of insulator proteins in delimiting TAD boundaries is strong, it is worth noting that only a portion of insulator binding sites function as TAD boundaries in mammalian and Drosophila cells37,40, and that many enhancer-promoter interactions cross CTCF binding events in a variety of mammalian cells types44. More work will therefore be required to determine the necessary and sufficient constituents of TAD boundary delimiters.

Albeit in flies the interactions of TADs has been described37 (see above), the extent to which mammalian TADs interact with each other, and the mechanistic logic behind these interactions, remains unclear. Distal chromatin interactions between loci many millions of bases (Mb) apart, or in trans, have been demonstrated in a number of mammalian cell types by various 3C-based studies31,32,34,42,44, but these interactions have not been examined in the context of TADs. It has been shown that long-range chromatin contacts can be cell type-specific and can occur between regions of the genome enriched for the DNA binding motif of a given transcription factor or for genes regulated by the same trans acting factors48,49, or by binding of gene regulatory factors as has been demonstrated for PcG-regulated distal chromatin interactions in Drosophila37,50 (Figure 1). One may speculate that co-regulated TADs are brought together in physical space in mammalian genomes as a general rule. Comprehensive analysis of long-range interactions in a well-annotated cell type such as ESCs should contribute to a better understanding of this question, as gene regulatory networks are well understood3, and - in the case of mouse ESCs - are amenable to genetic manipulations, which can be used to test causal links between linear genomic features and genome organization both in pluripotency and during the course of differentiation.

The ESC genome in pluripotency and differentiation

The genomes of ESCs have a number of unique characteristics that distinguish them from somatic cell genomes. The contribution of these features to the different layers genome organization described above is currently unclear, however they may have an effect on the interpretation of organizational data in ESCs and thus are important to note. Among features unique to the genome of mouse ESCs are a hyper-dynamic association of chromatin proteins with the chromatin polymer51, enhanced global transcriptional activity52, a lack of condensed heterochromatin at the NE and peri-nucleolar regions53, and two active X-chromosomes in females cells. Upon differentiation, chromatin protein association becomes more stable51, wide-spread transcription of both protein coding and non-coding regions is restricted, repeat elements are silenced51,52, and heterochromatic regions of the genome compact and localize to the nuclear periphery53. At the same time, a subset of pluripotency gene loci is silenced and moves to the nuclear periphery even before germ layer restriction occurs53–56. These processes occur contemporaneously with large-scale changes in DNA replication timing54,55, silencing of an X-chromosome in female cells57, and the onset of Lamin A expression, which stabilizes histone H1 in heterochromatin and is required for the establishment of the large number of heterochromatin foci characteristic of differentiated cells58. Together, these data indicate that the dramatic changes in gene expression that occur upon pluripotent cell differentiation are accompanied by large-scale changes in genome topology.

Despite the correlation between NE localization and gene silencing in ESCs56, LaminB1/B2 double knockout ESCs and trophectoderm cells show few changes in gene expression compared to their respective wild-type cells, and those genes that do change expression levels are not bound by B-type Lamins in wild-type cells59. This suggests that LaminB does not directly regulate expression of its interacting genes in ESCs or trophectoderm cells. Alternatively, unidentified redundant mechanisms may work to maintain gene silencing at the NE in the absence of B-type lamins in these cells. Additionally, LaminB-null ESCs show none of the NE morphology defects typical of somatic cells with mutations in nuclear lamina proteins59,60. During the course of differentiation of ESCs to neural precursor cells, many pluripotency specific genes are re-localized to the nuclear lamina and many NPC-specific genes detach from the lamina56. In contrast to the phenotypically wild-type ESCs, upon embryonic development, LaminB1/B2-null mice display severe organogenesis and neural migration defects59. Implicated as a major player in somatic cell genome organization, it will be important to understand the role of the nuclear lamina in regulating genome organization of ESCs, or alternatively, to determine if chromatin-NE co-localization is only required upon differentiation.

In contrast to the transcriptionally repressive nuclear envelope, in yeast, gene localization to the nuclear pore complex is associated with transcriptional activation in certain inducible systems61. In metazoans, however, some of the nucleoporins (Nups), the major constituents of the nuclear pore complex, have been implicated as regulators of gene expression through direct binding of chromatin in the nucleoplasm, mostly away from the nuclear pore62–64. Specifically, Nup133-null mice display defects in neural differentiation and Nup133-null ESCs differentiate inefficiently along neural lineages and do not contribute to the neural tube of chimeric embryos65. Similarly, the integral membrane protein Nup210 is expressed cell type specifically and is, not essential for nuclear pore function, but is required for ESC differentiation into neural progenitors as well as for myogenesis. Nup210 depletion abrogates the upregulation of differentiation-associated genes and its overexpression facilitates the expression of essential differentiation genes. Notably, the authors argue against a role for Nup210 in tethering genes to the nuclear pore complex upon induction, as they do not see changes in candidate, Nup210 regulated gene localization to the NE66. It will be important to understand the differing roles of Nups when they are chromatin bound in the nucleoplasm, versus when they are part of the nuclear pore complex, as well as their role in genome organization or re-organization upon differentiation in metazoans.

Re-organization of the X chromosome during ESC differentiation

The X chromosome inactivation process is a striking example for topology changes associated with differentiation. The equalization of X-linked gene expression between sexes in mammals occurs via the silencing of one of two X chromosomes upon induction of differentiation of ESCs. This process, induced by the upregulation and spreading of the non-coding RNA Xist on the future inactive X chromosome (Xi), leads to the transcriptional silencing of the majority of X-linked genes on the Xi, and the establishment of a number of repressive chromatin modifications along the Xi, including Polycomb group protein-mediated H3K27 methylation, DNA methylation, and deposition of the histone variant macroH2A57.

At the onset of X-inactivation homologous X chromosomes co-localize allowing for the pairing of the Xist-encoding X-inactivation centers (XIC), a process thought to be necessary for the initiation of X-inactivation on one of the two X chromosomes67–69. Following X-chromosome pairing, the Xi preferentially localizes to the NE and peri-nucleolar regions of the nucleus70, both of which are enriched for autosomal heterochromatin in differentiated cells71. This localization occurs predominantly during S phase of the cell cycle, and is dependent on Xist expression. Deletion of Xist in fibroblasts causes a re-localization of the Xi away from the nucleolus, with concomitant re-activation of a subset of genes in small proportion of cells70.

In addition to these large scale movements of the X-chromosome upon induction of X-inactivation, Xist expression leads to the formation of an Xist RNA domain over one of the two X-chromosomes and the immediate exclusion of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) and transcription machinery from the future Xi19. Interestingly, the exclusion of transcription machinery precedes the completion of transcriptional silencing. At the time of transcription machinery exclusion from the territory of the Xi, genes localize to the periphery of the X chromosome territory, where they can contact the transcriptional machinery. As these genes are silenced during the course of differentiation and X-inactivation, they localize to the interior of the Xi territory. Silencing and sequestration of X-linked genes into the Xi territory requires the A-repeat19, a portion of Xist necessary for transcriptional silencing72. Genes that escape X-inactivation remain localized to the periphery of the Xi territory19. A subsequent 4C study has shown that these escaping genes co-localize with other escaping genes as well as with gene loci on other chromosomes73. Conversely, silenced genes in the center of the Xi territory make few preferential interactions with other genomic regions, suggesting a random localization or restricted movement of these loci within the Xi73. Xi-specific 3D chromatin organization is partially dependent on Xist RNA coating, as Xist deletion results in an organizational state of the Xi resembling the Xa19,73.

The mechanisms regulating the dramatic re-organization of the X-chromosome upon silencing are unclear, however, SatB1/B2 are implicated in this process74. In thymocytes, the SatB1 protein is organized in a cage-like structure throughout the nucleus75 where it regulates gene expression through the anchoring of looped chromatin structures and the recruitment of chromatin modifying enzymes76,77. Upon induction of Xist expression in thymocytes and ESCs, Xist RNA accumulates in a region delimited by SatB1, and SatB1 depletion during ESC differentiation reduces the efficiency of X-inactivation74, although MEFs derived from SatB1/B2-null embryos display normal X-inactivation78,79, calling into question an essential role for SatB1 in the organization of chromatin and gene silencing during X-inactivation.

Despite the large-scale re-organization of the X chromosome during the course of inactivation, the existence of the two TADs encompassing the XIC does not change. However, specific intra-TAD interactions are lost upon X-inactivation, suggesting a random organization of the intra-TAD space within the Xi41, similar to that shown for long-range interactions with in the Xi by 4C analysis73. Alternatively, molecular ‘gluing’ of these TADs to the nuclear lamina could lead to a very limited interactome. Cell lines lacking G9a, an H3K9 methyltransferase, or Eed, an essential component of the Polycomb repressive complex 2, have no effect on the chromatin conformation or TAD structure within the XIC, suggesting that epigenetic modifications function downstream of TAD formation. In contrast, deletion of the TAD boundary region in the XIC, specifically between Xist and Tsix, resulted in the partial merger of neighboring TADs in mouse ESCs41, although cells lacking this TAD boundary are still capable of undergoing random X-inactivation upon differentiation80, leaving open the question of whether a specific organization of the XIC is required for X-inactivation.

Together, these data argue that X-inactivation is an essential developmental process that is associated with topology changes at various levels and may be a great model system to dissect the molecular mechanisms underlying genome organization and its dynamics during the course of differentiation. Notably, the 3D organization of the X-chromosome during Xi-reactivation events in vitro or in vivo, either in the context of somatic cell reprogramming81 or germ cell development82, has not been investigated.

Mechanistic insights into genome organization

Based on studies of promoter and enhancer interactions by DNA looping, it is clear that gene expression is facilitated and regulated through contacts of distal chromatin contacts. The mode and mechanism of action of enhancer elements has been the subject a large body of work over the years, and recent experiments have brought to light various molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. In particular, the Cohesin complex – which, canonically, forms a ring around sister chromatids during mitosis83 - has been shown to play a major role in organizing DNA topology and affecting gene regulatory processes at the level of enhancer-promoter interactions. It was initially characterized at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus in T-cells where it is required for enhancer-promoter looping and expression of IFNG84, and at the H19/IF2 loci in humanized mouse cells where it is required for insulator activity85. Cohesin binding sites overlap significantly with CTCF binding sites genome wide85–88, many of which are conserved across cell types and species47, leading to a model wherein CTCF-associated Cohesin localization is largely cell type invariant89 (Figure 1b,c), potentially explaining the conservation of TAD boundaries across cell types and species, as hypothesized by Dixon et al40,47.

In order to generate cell-type specific DNA topologies for the facilitation of specific transcriptional programs, cells appear to utilize non-CTCF mediated recruitment of Cohesin. For instance, Cohesin is co-bound with the transcription factor CEBPA in Hep2G cells and with the estrogen receptor (ER) in MCF7 cells, where Cohesin binding persists in the absence of CTCF90. In the case of MCF7 cells, Cohesin binding is particularly enriched at regions involved in ER-mediated chromatin interactions38. Mounting evidence suggests that, similar to its role during mitosis, Cohesin functions by holding functional DNA elements together in the nucleus (Figure 2), and additionally, may stabilize TF binding to highly occupied cis regulatory elements91.

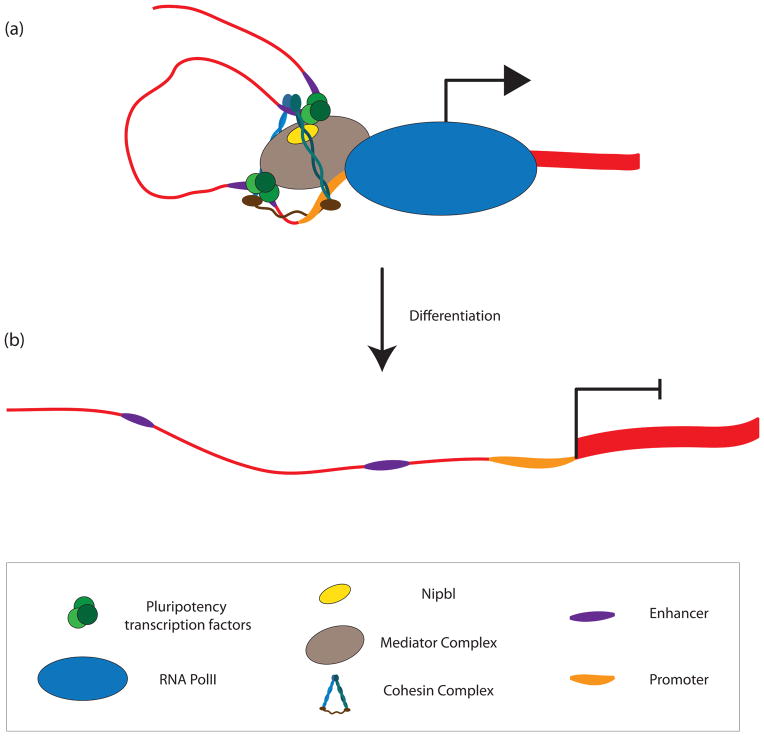

Figure 2. The Mediator complex recruits Cohesin to chromatin and facilitates cell-type specific enhancer-promoter looping and gene expression.

(a) Mediator-recruited Cohesin complexes orchestrate cell-type specific enhancer-promoter loops, providing a mechanism for the cell-type specific action of an enhancer on a given promoter and, by extension, cell-type specific gene expression patters. In ESCs, many Oct4 (O), Sox2 (S), and Nanog (N) bound regions of the genome coincide with Mediator and Cohesin occupancy, indicating that these transcription factors recruit mediator to enhancers and promoters. (b) In fibroblasts, where OSN are not expressed, Mediator and Cohesin show differential DNA binding patterns and enhancer-promoter looping events at ESC-specific gene loci are absent.

A major advance in our understanding of the mechanistic underpinnings of promoter-enhancer interactions in ESCs was achieved recently through an shRNA screen for loss of Oct4 gene expression89. This screen identified numerous subunits of Mediator - a massive protein complex that regulates the activity of RNA Polymerase II92 - and Cohesin subunits, as well as the Cohesin loading factor Nipbl, as regulators of Oct4 gene expression. The authors found that Cohesin and Mediator co-immunoprecipitate with each other and Nipbl in ESCs, potentially allowing Cohesin to enable ESC-specific enhancer-promoter interactions upon recruitment of Mediator to chromatin by various transcription factors (Figure 2). Unlike CTCF and Cohesin co-bound sites, Mediator and Cohesin co-bound sites are cell type-specific and often overlap with locations of pluripotency transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog in ESCs. In MEFs, among loci where Mediator binding is different compared to ESCs, enhancer-promoter looping interactions are likewise different, as shown using 3C at a number of candidate loci89. These findings likely explain previous work demonstrating a chromatin topology that brings together a variety of DNase HS sites and co-regulated genes within the extended 150kb Nanog locus, a topology that is lost upon Oct4 depletion93. Although it has not been explicitly demonstrated outside of ESCs, we speculate that recruitment of mediator to binding sites occupied by cell type-specific transcription factors facilitates the recruitment of Cohesin to interphase chromatin where it mediates enhancer-promoter interactions, and potentially even more long-range chromatin contacts.

Conclusions and Outlook

The synthesis of recently published data leads us to propose the following speculative model of mammalian genome organization (Figure 1): Within TADs37,40,41, enhancers and promoters dynamically co-localize with and co-regulate each other44,94 in a cell type-specific manner44, limited in range along the chromatin polymer by TAD boundaries41,43. These TADs, existing as topologically isolated loops42, can re-locate to various sub-nuclear compartments18,34,41,56 in response to specific developmental and gene regulatory cues, but apart from limited cases where specific genes (and likely entire TADs) loop out of their CTs, TAD localization is limited to its own CT. An important piece of information missing from this model is the mode and mechanism of preferential TAD-TAD interactions that we infer from 4C data. Due to their well-defined transcriptional networks, chromatin states, and gene expression data sets, ESCs - in pluripotency and during the course of differentiation - will be an ideal cell type for studying this question with 3C-based methodologies. In combination with a transcriptionally permissive nuclear environment52 and a lack of highly condensed heterochromatin53, future studies may also help us to understand whether an ESC-specific 3D genomic organization contributes to the developmental plasticity of ESCs.

Acknowledgments

KP is supported by the NIH (DP2OD001686 and P01 GM099134), CIRM (RN1-00564 and RB3-05080), and by the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. MD is supported by the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA, CIRM (TG2-01169), and the UCLA graduate division.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–6. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson JA, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RA. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011;144:940–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahl PB, et al. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell. 2010;141:432–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer LA, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–53. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao R, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, et al. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. 2004;431:873–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eskeland R, et al. Ring1B compacts chromatin structure and represses gene expression independent of histone ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2010;38:452–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niwa H, Ogawa K, Shimosato D, Adachi K. A parallel circuit of LIF signalling pathways maintains pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Nature. 2009;460:118–22. doi: 10.1038/nature08113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu RH, et al. Basic FGF and suppression of BMP signaling sustain undifferentiated proliferation of human ES cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:185–90. doi: 10.1038/nmeth744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cremer T, Cremer C. Rise, fall and resurrection of chromosome territories: a historical perspective. Part II. Fall and resurrection of chromosome territories during the 1950s to 1980s. Part III. Chromosome territories and the functional nuclear architecture: experiments and models from the 1990s to the present. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:223–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle S, et al. The spatial organization of human chromosomes within the nuclei of normal and emerin-mutant cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:211–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warburton D, Naylor AF, Warburton FE. Spatial relations of human chromosomes identified by quinacrine fluorescence at metaphase. I. Mean interchromosomal distances and distances from the cell center. Humangenetik. 1973;18:297–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00291126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parada LA, McQueen PG, Misteli T. Tissue-specific spatial organization of genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-7-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cremer T, Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:292–301. doi: 10.1038/35066075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cremer T, Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003889. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambeyron S, Bickmore WA. Chromatin decondensation and nuclear reorganization of the HoxB locus upon induction of transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1119–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Chaumeil J, Le Baccon P, Wutz A, Heard E. A novel role for Xist RNA in the formation of a repressive nuclear compartment into which genes are recruited when silenced. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2223–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.380906. This work describes the localization of X-linked genes relative to the territory of the X chromosome during initiation of X-inactivation. It additionally characterizes the role of the Xist silencing domain in the relocalization of genes during X-inactivation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrulis ED, Neiman AM, Zappulla DC, Sternglanz R. Perinuclear localization of chromatin facilitates transcriptional silencing. Nature. 1998;394:592–5. doi: 10.1038/29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosak ST, et al. Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science. 2002;296:158–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1068768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickersgill H, et al. Characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster genome at the nuclear lamina. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1005–14. doi: 10.1038/ng1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumaran RI, Spector DL. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:51–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schirmer EC, Foisner R. Proteins that associate with lamins: many faces, many functions. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattout A, Goldberg M, Tzur Y, Margalit A, Gruenbaum Y. Specific and conserved sequences in D. melanogaster and C. elegans lamins and histone H2A mediate the attachment of lamins to chromosomes. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:77–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao J, Fetter RD, Hu P, Betzig E, Tjian R. Subnuclear segregation of genes and core promoter factors in myogenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:569–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zullo JM, et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell. 2012;149:1474–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hakim O, Misteli T. SnapShot: Chromosome confirmation capture. Cell. 2012;148:1068 e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simonis M, et al. Nuclear organization of active and inactive chromatin domains uncovered by chromosome conformation capture-on-chip (4C) Nat Genet. 2006;38:1348–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Z, et al. Circular chromosome conformation capture (4C) uncovers extensive networks of epigenetically regulated intra- and interchromosomal interactions. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1341–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dostie J, et al. Chromosome Conformation Capture Carbon Copy (5C): a massively parallel solution for mapping interactions between genomic elements. Genome Res. 2006;16:1299–309. doi: 10.1101/gr.5571506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lieberman-Aiden E, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan Z, et al. A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature. 2010;465:363–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalhor R, Tjong H, Jayathilaka N, Alber F, Chen L. Genome architectures revealed by tethered chromosome conformation capture and population-based modeling. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:90–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Sexton T, et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell. 2012;148:458–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.010. This study was the first to identify topological domains as a unit of metazoan genome organization, and presented evidence for a heirarchical organization of the genome as illustrated in Figure 1, as well as for Polycomb-mediated long-range chromatin interactions genome wide. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fullwood MJ, et al. An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462:58–64. doi: 10.1038/nature08497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, et al. Spatial organization of the mouse genome and its role in recurrent chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2012;148:908–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Dixon JR, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. This study demonstrated the existence of TADs in mammalian cells and showed them to be conserved across cell types and human and mouse cell types. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41**.Nora EP, et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature. 2012;485:381–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11049. This work showed that genes within TADs, specifically within the Xist/Tsix containing TADs of the X-inactivation centre are coordinately regulated during the course of differentiation, that TADs remain static during the course of XCI, and that deletion of a TAD boundary region results in ectopic chromatin interactions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42**.Handoko L, et al. CTCF-mediated functional chromatin interactome in pluripotent cells. Nat Genet. 2011;43:630–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.857. This study demonstrated the role of CTCF in ESCs as an organizer of large chromatin loops containing distinct epigenetic modifications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43**.Shen Y, et al. A map of the cis-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature. 2012;488:116–20. doi: 10.1038/nature11243. Using ChIP-seq and RNA-seq across a wide variety of cell lines for a large number of transcription factors and chromatin modifications, this study demonstrated that TADs function as domains of coordinately regulated enhancers and promoters in mammalain cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G, Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature. 2012;489:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature11279. As part of the recently released ENCODE consortium data, this work demonstrated the promiscuity of enhancer elements in contacting numerous gene promoters, explicitly demonstrating that genes in contact with enhancers are more highly expressed than those without enhancer contacts across ENCODE analyzed regions of the genome, and explored the enrichment of numerous chromatin modifications taking part in looping interactions across a number of cell types. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood AM, et al. Regulation of chromatin organization and inducible gene expression by a Drosophila insulator. Mol Cell. 2011;44:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell AC, West AG, Felsenfeld G. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell. 1999;98:387–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt D, et al. Waves of retrotransposon expansion remodel genome organization and CTCF binding in multiple mammalian lineages. Cell. 2012;148:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noordermeer D, et al. Variegated gene expression caused by cell-specific long-range DNA interactions. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:944–51. doi: 10.1038/ncb2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoenfelder S, et al. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:53–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bantignies F, et al. Polycomb-dependent regulatory contacts between distant Hox loci in Drosophila. Cell. 2011;144:214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meshorer E, et al. Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;10:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Efroni S, et al. Global transcription in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:437–47. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmed K, et al. Global chromatin architecture reflects pluripotency and lineage commitment in the early mouse embryo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hiratani I, et al. Genome-wide dynamics of replication timing revealed by in vitro models of mouse embryogenesis. Genome Res. 2010;20:155–69. doi: 10.1101/gr.099796.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hiratani I, et al. Global reorganization of replication domains during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peric-Hupkes D, et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol Cell. 2010;38:603–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minkovsky A, Patel S, Plath K. Concise review: Pluripotency and the transcriptional inactivation of the female Mammalian X chromosome. Stem Cells. 2012;30:48–54. doi: 10.1002/stem.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melcer S, et al. Histone modifications and lamin A regulate chromatin protein dynamics in early embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:910. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim Y, et al. Mouse B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis but not by embryonic stem cells. Science. 2011;334:1706–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1211222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Capell BC, Collins FS. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:940–52. doi: 10.1038/nrg1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan-Wong SM, Wijayatilake HD, Proudfoot NJ. Gene loops function to maintain transcriptional memory through interaction with the nuclear pore complex. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2610–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1823209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Capelson M, et al. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 2010;140:372–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaquerizas JM, et al. Nuclear pore proteins nup153 and megator define transcriptionally active regions in the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lupu F, Alves A, Anderson K, Doye V, Lacy E. Nuclear pore composition regulates neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation in the mouse embryo. Dev Cell. 2008;14:831–42. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.D’Angelo MA, Gomez-Cavazos JS, Mei A, Lackner DH, Hetzer MW. A change in nuclear pore complex composition regulates cell differentiation. Dev Cell. 2012;22:446–58. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bacher CP, et al. Transient colocalization of X-inactivation centres accompanies the initiation of X inactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:293–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu N, Tsai CL, Lee JT. Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science. 2006;311:1149–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1122984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masui O, et al. Live-cell chromosome dynamics and outcome of X chromosome pairing events during ES cell differentiation. Cell. 2011;145:447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang LF, Huynh KD, Lee JT. Perinucleolar targeting of the inactive X during S phase: evidence for a role in the maintenance of silencing. Cell. 2007;129:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao R, Bodnar MS, Spector DL. Nuclear neighborhoods and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wutz A, Rasmussen TP, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal silencing and localization are mediated by different domains of Xist RNA. Nat Genet. 2002;30:167–74. doi: 10.1038/ng820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Splinter E, et al. The inactive X chromosome adopts a unique three-dimensional conformation that is dependent on Xist RNA. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1371–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.633311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agrelo R, et al. SATB1 defines the developmental context for gene silencing by Xist in lymphoma and embryonic cells. Dev Cell. 2009;16:507–16. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cai S, Han HJ, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Tissue-specific nuclear architecture and gene expression regulated by SATB1. Nat Genet. 2003;34:42–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1278–88. doi: 10.1038/ng1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yasui D, Miyano M, Cai S, Varga-Weisz P, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 targets chromatin remodelling to regulate genes over long distances. Nature. 2002;419:641–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nechanitzsky R, Dávila A, Savarese F, Fietze S, Grosschedl R. Satb1 and Satb2 Are Dispensable for X Chromosome Inactivation in Mice. Dev Cell. 2012;23:866–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wutz A, Agrelo R. Response: The Diversity of Proteins Linking Xist to Gene Silencing. Dev Cell. 2012;23:680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monkhorst K, Jonkers I, Rentmeester E, Grosveld F, Gribnau J. X inactivation counting and choice is a stochastic process: evidence for involvement of an X-linked activator. Cell. 2008;132:410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maherali N, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sasaki H, Matsui Y. Epigenetic events in mammalian germ-cell development: reprogramming and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:129–40. doi: 10.1038/nrg2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haering CH, Farcas AM, Arumugam P, Metson J, Nasmyth K. The cohesin ring concatenates sister DNA molecules. Nature. 2008;454:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nature07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hadjur S, et al. Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature. 2009;460:410–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wendt KS, et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parelho V, et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubio ED, et al. CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801273105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stedman W, et al. Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. EMBO J. 2008;27:654–66. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89**.Kagey MH, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. Kagey et al. described the role of Mediator and Cohesin in mediating enhancer promoter looping in ESCs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmidt D, et al. A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription. Genome Res. 2010;20:578–88. doi: 10.1101/gr.100479.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Faure AJ, et al. Cohesin regulates tissue-specific expression by stabilizing highly occupied cis-regulatory modules. Genome Res. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.136507.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taatjes DJ. The human Mediator complex: a versatile, genome-wide regulator of transcription. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:315–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levasseur DN, Wang J, Dorschner MO, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Orkin SH. Oct4 dependence of chromatin structure within the extended Nanog locus in ES cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:575–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1606308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li G, et al. Extensive promoter-centered chromatin interactions provide a topological basis for transcription regulation. Cell. 2012;148:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]