Abstract

Human and mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) genes are diversified in mature B cells by distinct processes known as Ig heavy chain class switch recombination (CSR) and Ig variable region exon somatic hypermutation (SHM). These DNA modification processes are initiated by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a DNA cytidine deaminase predominantly expressed in activated B cells. AID is post-transcriptionally regulated via multiple mechanisms including microRNA regulation, nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling, ubiquitination and phosphorylation. Among these regulatory processes, AID phosphorylation at Serine-38 (S38) has been a focus of particularly intense study and debate. Here, we discuss recent biochemical and mouse genetic studies that begin to elucidate the functional significance of AID S38 phosphorylation in the context of the evolution of this mode of AID regulation and the potential roles that it may play in activated B cells during a normal immune response.

Keywords: activation-induced cytidine deaminase, class switch recombination, evolution, phosphorylation, somatic hypermutation

1. INTRODUCTION

Antibodies are comprised of Ig heavy (IgH) and light (IgL) chains. The N-terminal variable region of IgH and IgL chains comprise the antigen-binding portion of antibody molecules; while the C-terminal constant region of the IgH chain determines effector functions of the molecule, such as where it goes in the body and which downstream pathways it activates to eliminate antigen. There are three somatic DNA alteration events that enable mammalian B lymphocytes to generate an antibody repertoire with enormous diversity and an array of effector functions. Developing B cells undergo V(D)J recombination to assemble exons encoding the IgH and IgL variable (V) regions from a large set of germline encoded V, D, and J gene segments. The V(D)J exon is assembled just upstream of the IgH Cμ constant region exons leading to expression of Ig μ heavy chains. Following the productive assembly of an IgL variable region exon, the μ heavy chain and IgL chain associate to produce IgM, which is expressed as a receptor on the surface of the newly generated B cell. Thereafter, the B cells migrate to secondary lymphoid organs where, upon encounter of cognate antigen, they can be activated to undergo two additional genetic alterations of their Ig genes, namely IgH and IgL variable region exon SHM which further diversifies the V(D)J exon and IgH CSR that allows expression of different IgH constant regions (CH regions) and hence different classes of antibody [1, 2]. Though two distinct processes, CSR and SHM absolutely require both transcription through the relevant Ig loci and AID [3-5]. AID is a single-stranded (ss)DNA-specific cytidine deaminase, expressed primarily in activated B cells [6-10]. Most evidence indicates that AID initiates CSR and SHM by deaminating cytidines to uracils in DNA although there are other views (see [11] for review). This article will focus on the post-translational regulation of AID by phosphorylation during CSR and SHM in B cells.

2. CLASS SWITCH RECOMBINATION

The IgH V(D)J exon is assembled upstream of the Cμ constant region exons, leading to generation of μ heavy chains. Additional sets of CH exons (Cγ, Cα and Cε) are located 100 to 200 kb downstream of Cμ. All of the different sets of CH exons that undergo CSR are flanked upstream by large (1–10 kb), repetitive “switch” (S) regions, which contain an abundance of so-called SHM motifs (see Figure 1 and below). CSR involves the introduction of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) into the “donor” Sμ region and into a downstream “acceptor” S region followed by joining of the donor and acceptor S regions. This CSR process juxtaposes a new downstream set of CH exons in place of the Cμ exons, allowing expression of the V(D)J exon with a different set of CH exons. An activator- and cytokine-specific promoter precedes each S region. Activation of these “germline” promoters and transcription through the corresponding S region is required to target CSR [11]. Such transcription directs the activity of AID to the targeted S region, which is essential for initiating the DSB-inducing process [12, 13]. In this context, mice with targeted deletion of the AID gene or human patients harboring loss-of-function AID mutations are unable to undergo CSR and express higher levels of IgM antibodies [3, 5]. AID initiates CSR by deaminating cytidine residues in transcribed S regions, leading to the generation of uracil lesions in DNA. The resulting U/G mismatches appear to be converted into DSBs through the co-opted activities of the base excision repair (BER) and mismatch repair (MMR) pathways [14, 15]. Once DSBs have been generated in two separated S regions, they are synapsed, apparently in large part by general cellular mechanisms [16], and joined, predominantly by the non- homologous end-joining pathway but also by an alternative end-joining pathway [17].

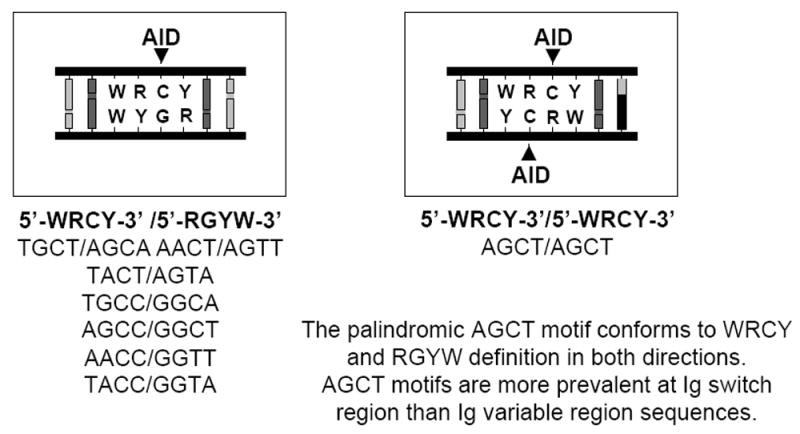

Figure 1. Schematic representation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) target preferences.

In vitro, AID preferentially deaminates C residues in DNA to uracil in the context of a WRCY sequence motif (W = A or T, R = A or G, Y = C or T; the target of AID within the motif is underlined) [20-21]. Seven of the eight possible tetranucleotide permutations of this motif conform to 5’-WRCY-3’/5’-RGYW-3’ sequence structure in double-stranded (ds)DNA (left); in this context, a single AID-mediated deamination event is possible within each double-stranded motif (as indicated). The palindromic sequence AGCT is unique in that it conforms to 5’-WRCY-3’/5’-WRCY-3’ sequence structure in dsDNA (right); in this context, AID-mediated deamination events are potentially possible on both strands of the DNA duplex within the same double-stranded motif (as indicated). Switch regions contain a higher density of AGCT motifs than variable regions; AGCT motifs are often tandemly repeated within core switch sequences. AID-mediated deamination of C residues at switch and variable regions in vivo co-opts activities of the base excision repair (BER) and mismatch repair pathways [28]. The BER pathway is apparently the dominant pathway during CSR in vivo; it is thought that uracil-N glycosylase (UNG) removes AID-generated U lesions leading to subsequent endonuclease cleavage of the phosphodiester bond 5’ of the resultant abasic site [29]. AID-mediated deamination of cytosine residues on both DNA strands within the same or neighboring 5’-AGCT-3’/5’-AGCT-3’ motifs and processing of the resultant U lesions via activity of the BER pathway theoretically could lead to the efficient formation of the double strand breaks that are required for CSR.

3. SOMATIC HYPERMUTATION

During an immune response, the SHM process can introduce substitution mutations at a very high rate (estimated to be ~10-3 to 10-4/base pair/generation) [18] into the IgH and IgL variable region exons of activated B cells, ultimately allowing selection of B cells with increased affinity for antigen [19]. SHM at C/G pairs occurs preferentially at RGYW and WRCY DNA motifs (R = A or G, Y = C or T, W = A or T; mutated position underlined), which are particularly abundant in the DNA sequences that encode the variable region complementarity determining regions, the site of the majority of the antigen contact residues. Biochemical studies suggest that the WRCY motif is a preferential target for AID (Figure 1) [20-23]. In this context, CSR regions are also particularly rich in such motifs, most notably the AGCT sequence. SHM requires transcription, with mutations starting from about 100-200bp downstream from the V exon promoter and extending 1.5-2kb downstream, generally sparing the CH exons. SHM also occurs at significant levels in S regions and their immediate flanking sequences during CSR, presumably as a by-product of AID generating S region DSBs [24]. In addition, SHM occurs in certain non-Ig genes, although at much lower levels than in S region and V(D)J exon targets during CSR and SHM [25-27]. The mechanisms that lead to such precise targeting of AID are still under investigation; although some mechanisms that may help contribute to this specificity will be a topic of this review. Mice and human patients with loss-of-function mutations of AID fail to undergo SHM, indicating an essential role for AID in this process as well as in CSR [3, 5]. SHM also appears to be initiated by C to U deamination in DNA [2, 11]. AID-generated U lesions in DNA template transition hypermutations at C/G pairs and also co-opt activities of the BER and MMR pathways (resulting in the generation of the complete spectrum of hypermutations at C/G and A/T pairs) [28, 29].

4. POTENTIAL MECHANISMS FOR AID ACCESS TO DUPLEXED DNA DURING CSR AND SHM

Several potential mechanisms have been elucidated for transcription-dependent AID access to double-stranded (ds)DNA [30-33]. In this review, we will focus on just two potential mechanisms that have been the focus of studies in our labs; one mechanism involves R-loops and the other involves replication protein A (RPA). Other potential mechanisms will be mentioned in the last section of the review.

Mouse AID (mAID) has been shown to be a ssDNA-specific cytidine deaminase which deaminates ssDNA substrates in vitro, but does not deaminate dsDNA substrates, except under certain conditions [6, 33]. Several mechanisms have been implicated in AID access to duplex V(D)J exons and S regions in vivo. Because of their high G/C content and G richness on the non-template strand, mammalian S regions generate ssDNA within R-loops transcribed in the physiologic direction [34-36]. In vitro purified mAID deaminates the non-template strand of T7 RNA polymerase-transcribed dsDNA sequences that form R-loops (e.g., S regions in sense orientation) but not transcribed dsDNA sequences that do not form R-loops [6, 33]. Moreover, gene-targeting experiments showed that optimal S region function in vivo depends on transcriptional orientation, supporting the notion that S region transcription might allow AID access to ssDNA in S regions via R-loop formation. Thus, R-loop forming ability may have evolved in mammalian S regions to enhance AID access during CSR [35].

Variable region exons do not form R-loops [33]. In vitro assays led to the identification of RPA, a trimeric ssDNA binding protein involved in replication and repair, as a factor that allowed purified B cell mAID to deaminate transcribed SHM substrates, which contained repeated AGCT motifs but which did not form R-loops [33]. The 32-kDa subunit of RPA interacts with purified B cell mAID, and the AID/RPA complex binds to transcribed WRCY/RGYW-containing DNA in vitro, apparently promoting AID deamination of the substrates predominantly within or near SHM motifs. It has been proposed that the AID/RPA complex may bind to and stabilize ssDNA within transcription bubbles to allow AID to access ssDNA substrates [33]. These overall findings led to the proposal that AID may access transcribed variable regions, in the absence of R-loops, via an RPA-dependent mechanism [11, 33].

Both AID and Ig gene SHM occur in bony fish [37-39]. However, CSR first occurs evolutionarily in amphibians, leading to the suggestion that CSR may have evolved after SHM [40-42]. Xenopus Sμ (XSμ) is A/T rich and does not form R-loops when transcribed in vitro [23, 40]. Yet, XSμ can replace mouse Sγ1 to promote substantial CSR in mouse B cells [23]. CSR junctions within XSμ in mice occurred in a region of densely packed AGCT sequences in the 5’ portion of XSμ; when this sequence was inverted in vivo, CSR junctions tracked with the AGCT motifs. Likewise, the AGCT repeat region was the predominant site of deamination by mAID/RPA in the context of an in vitro transcription-dependent deamination assay, regardless of orientation [23]. Based on these findings, it was suggested that CSR evolved from SHM with the early S regions in amphibians being sequences with a high density of SHM motifs that facilitated AID access via an RPA-dependent mechanism. Given that mammalian S regions are also dense in SHM motifs (notably AGCT motifs), these findings further raised the possibility that AID may access mammalian S regions via an RPA-dependent mechanism and that R-loop based mechanisms of access may have arisen later in evolution to further facilitate targeting of AID activity [23]. Because the high density of AID-preferred AGCT motifs appears to target DSBs in XSμ, it seems possible that the higher density of these motifs in IgH S regions versus Ig variable region exons may contribute to the DSB formation (and hence CSR) versus SHM outcome of AID deamination at these sites, respectively [11].

5. POST-TRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATION OF AID BY PHOSPHORYLATION

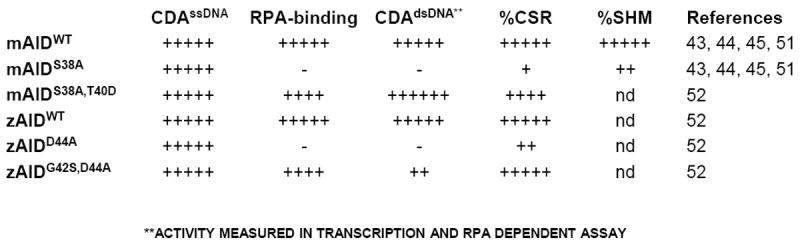

Mammalian AID is phosphorylated on multiple residues. Purified B cell mAID is phosphorylated at S38, Tyrosine-184 (Y184) and Threonine-140 (T140) [43-45]. Thus far, only the functional significance of S38 phosphorylation has been elucidated in detail. The ability of AID to interact with RPA and function in transcription-dependent dsDNA deamination assays depends on phosphorylation at S38 [33, 43]. The S38 residue exists in a cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) consensus motif; accordingly, mAID can be phosphorylated in vitro on S38 by PKA. In addition, a variety of evidence suggests that PKA also phosphorylates mAID on S38 in cells, including activated B cells [43, 46]. Mouse AID that is not phosphorylated on S38 does not bind RPA and does not mediate dsDNA deamination of transcribed AGCT-rich substrates in vitro [43], with both activities, however, being restored by in vitro PKA phosphorylation of non-phosphorylated mAID [43]. Correspondingly, a mutant form of mAID in which the S38 residue was changed to alanine (mAIDS38A) retains ssDNA deamination activity, but lacks ability to be phosphorylated by PKA and fails to interact with RPA or function in transcription-dependent dsDNA deamination assays [43]. Mouse AIDS38A also had reduced CSR activity (15-30% of WT activity) in activated AID-deficient B cells when ectopically introduced via a retroviral expression vector (Figure 2) [43, 44, 46, 47]. Likewise, drug-induced PKA inhibition decreased CSR, and PKA activation via deletion of the PKA negative regulatory subunit increased CSR in vivo [46]. Together, these studies supported a model that proposed mammalian AID phosphorylation at S38 is a mechanism for augmenting the ability of AID to access S region DNA and initiate CSR. In this context, a similar ex vivo system to test AID SHM activity in mouse B cells does not exist, but AIDS38A was found to have reduced capacity to mediate SHM in substrates introduced into mouse non-lymphoid cells and in Ig genes in chicken DT40 cells [44, 48].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of different in vitro and in vivo activities of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) mutant proteins.

The in vitro biochemical activities of each of the proteins presented are its cytidine deaminase activity on single-stranded (ss)DNA (CDAssDNA) or on transcribed RGYW-rich double-stranded (ds)DNA (CDAdsDNA). The ability of each protein to bind to replication protein A (RPA) in vitro is also represented (RPA-binding). The class switch recombination (CSR) or somatic hypermutation (SHM) in vivo activities of each protein represents data obtained from retroviral complementation assays or from knock-in mouse models. “nd” represents “not done”.

Despite the strong circumstantial evidence outlined above which points to a potential role for AID phosphorylation during CSR and SHM, this form of AID regulation has been the subject of significant debate. A major argument against this form of AID regulation came from a study that reported that retrovirally-driven expression of the AIDS38A mutant protein in AID-deficient B cells restored CSR to nearly WT levels [49]. However, given that the AIDS38A protein is a hypomorphic mutant with full ssDNA deamination activity these apparently discrepant findings might have resulted from overexpression levels that allowed the mutant to “catch-up” with WT activity [43, 44, 46, 47]. In another study, the AIDS38A protein purified from insect cell lines appeared to have similar activity as AIDWT protein in a transcription-dependent DNA deamination assay [50]. However, in this case, the substrate sequences employed had a high GC content which could generate R-loops upon transcription and allow RPA-independent access via the R-loop mechanism [6, 35]. Another point used to question the role of AID S38 phoshorylation was based on the observation that zebrafish AID (zAID), which lacks a PKA consensus motif and an S38 equivalent residue at the corresponding position to mAID, is able to catalyze robust CSR in mouse B cells [48, 49]. In this case, however, it was noted that such activity might be provided by a nearby aspartate residue (D44), which theoretically could allow zAID to mimic S38-phosphorylated mAID (Figure 3). Finally, it was noted that a putative molecular mimic of AID phosphorylated on S38 (replacement of S38 with an aspartic acid to generate AIDS38D) fails to undergo CSR at substantial levels (Figure 3) [44, 49]. However, it remained possible that this substitution might not fully mimic S38-phosphorylated AID or might have other unrelated effects on the protein. As discussed in detail in the following sections, each of these questions regarding the physiologic role of AID S38 phosphorylation has been addressed recently by either gene-targeted mutation studies [45, 51] or by studying the zAID activity in more depth [52].

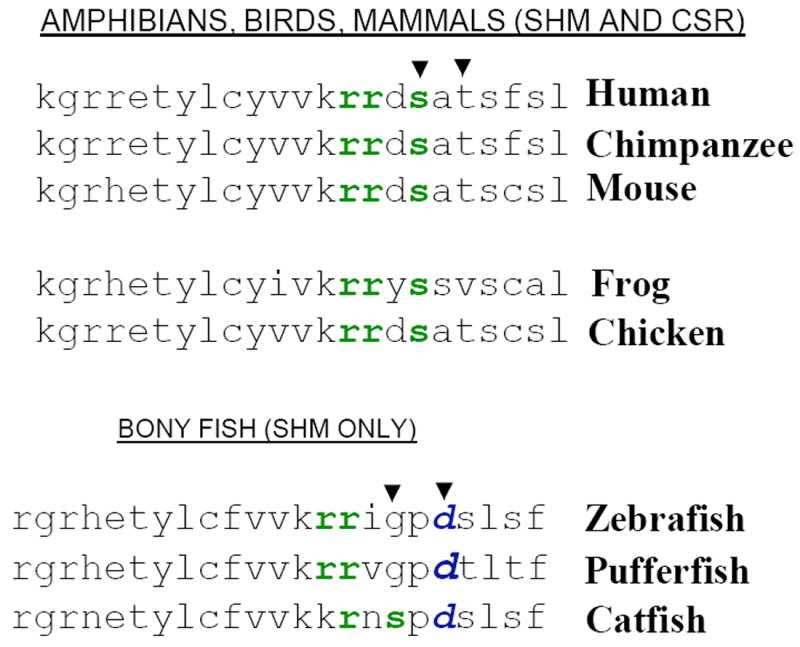

Figure 3. Conservation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) phosphorylation site Serine-38 in different species.

The protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation site of AID at Serine-38 is present in all organisms that undergo CSR (mammals, amphibians and birds) but is absent in organisms that undergo SHM only (bonyfish). The PKA consensus site is represented by “rrxs/t”, where “r” represents an arginine residue, “x” any amino acid and “s/t” represents “serine or threonine”. All bonyfish AID amino acid sequences contain an aspartic acid residue “d”, which is absent in the AID amino acid sequences of organisms that undergo CSR.

6. ANALYSIS OF CSR AND SHM IN AIDS38A KNOCK-IN MUTANT MICE

To address the physiological significance of AID phosphorylation at S38, analysis of a mouse model (in which AIDS38A is expressed at physiological levels utilizing its endogenous control elements) was required. Two recent studies reported the generation and analysis of mice expressing only the AIDS38A mutant protein, which occurred at levels quite comparable to those of WT mAID expression in activated B cells, from their endogenous AID alleles [45, 51]. In addition, one of these studies also demonstrated that the AIDS38A protein expressed from the endogenous AID allele failed to associate with RPA in vivo [51]. Both studies found that mice homozygous for the AIDS38A (AIDS38A/S38A) mutation have quite severe CSR defects, clearly demonstrating that the apparently normal levels of CSR reported for this mutant form of AID by others [49] likely resulted from over-expression of the mutant protein as proposed [47].

Activation of AIDS38A/S38A B cells with αCD40 plus IL-4 for 3 days (to induce CSR to Cγ1) resulted in IgG1 CSR levels that were only 5% of those of WT levels, with WT levels essentially reaching their maximum values by that day of activation [51]. After 4.5 days of αCD40 plus IL-4 treatment, the level of CSR of AIDS38A/S38A B cells reached 40-50% of the WT levels, likely reflecting the fact that WT B cells reached their maximum, plateau values by day 3.5 and that the AIDS38A/S38A hypomorphic mutant B cells were able to partially “catch-up” in the intervening day and a half of activation [45, 51]. On the other hand, activation of AIDS38A/S38A B cells with bacterial lipopolysacharride (LPS) plus anti–δ-dextran for 3 days (to induce CSR to Cγ3) led to barely detectable CSR to IgG3 at any of the measured time-points (less than 1% of WT levels) [51]. Thus, AIDS38A/S38A mutant B cells appear even more severely impaired for CSR to IgG3 than to IgG1. The more severe CSR defect for CSR to IgG3 might reflect several factors including a lower level of AID expression following LPS plus anti-δ-dextran stimulation [51] (see below for discussion of effects of AID levels on CSR) and/or the smaller size and different sequence of the Sγ3 target region as compared to the Sγ1 region, which theoretically could make Sγ3 a poorer AID target [51].

AID expression has been found to demonstrate haploinsufficiency, with AID+/- B cells having only about half the level of AID expression as AID+/+ WT B cells [45, 51, 53, 54]. In this context, AID+/- mice also tend to show proportionately reduced CSR [45, 51]; although in our experiments, we observe this reduction to be more marked for CSR to IgG3 than for CSR to IgG1 [45, 51] (see below). Remarkably, this haploinsufficiency effect was greatly magnified in the context of the AIDS38A mutation. Thus, AIDS38A/- B cells had dramatically reduced CSR to both IgG1 and IgG3, as compared to levels of AID+/- B cells after 3 or 4.5 days of stimulation for switching either to IgG1 or to IgG3 [45, 51]. In this case, IgG1 CSR of the AIDS38A/- B cells did not exceed 5% of control levels and CSR of AIDS38A/- B cells to IgG3 were at background AID-/- B cell levels [45, 51]. The potential significance of the haploinsufficiency phenotype will be discussed further below.

The activity of mAID in the transcription-coupled SHM assay in vitro is dependent on phosphorylation at S38 and RPA association and was abrogated by the S38A mutation [43, 52]. Therefore, it was hypothesized initially that the AIDS38A mutation might have a more severe effect on SHM than on CSR, in which AID might still access S region DNA via a R-loop mechanism [11, 33]. However, as mentioned earlier, no system existed to analyze the effect of the mAIDS38A mutation on SHM in B cells before the generation of AIDS38A/S38A mutant mice. Thus, the only previous assays to examine the effects of the AIDS38A mutation on SHM were done via the introduction of artificial substrates into fibroblast cells [44]. In contrast to expectations based on the in vitro transcription-dependent deamination assays, analyses of SHM just downstream of the rearranged V(D)J allele in the IgH locus (a standard assay for studying SHM in vivo) revealed that, while B cells from AIDS38A/S38A mice had significantly decreased SHM, substantial residual levels (30% of WT levels) remained [44]. Therefore, at least based on this particular SHM assay, CSR appears more severely impaired in AIDS38A/S38A mice than SHM. However, as observed for CSR in AIDS38A/- mutant mice, SHM levels in AIDS38A/- were found to be close to background levels and, thus, were dramatically decreased as compared to those of WT mice (which were only down approximately 50%) [45]. The latter finding suggests the possibility that, as observed with IgH CSR, SHM levels may also be closely titrated to AID levels in appropriately activated B cells. If so, by analogy to CSR, more severe effects of the AIDS38A mutation might be observed during SHM in particular physiological contexts in which AID induction levels are not as high as in others or in a substrate-dependent manner (e.g., similar to the potentially differing effects of the AIDS38A on CSR to Sγ1 versus Sγ3; see above). Of course, it is also possible that there are additional mechanisms that promote AID access, or downstream functions during SHM that are not dependent on S38 phosphorylation (see below for further discussion).

7. EVOLUTION OF AID PHOSPHORYLATION AT SERINE-38

Bony fish undergo SHM but do not undergo CSR, potentially because they lack the CSR target sequences (e.g., S regions and different sets of CH exons). In this context, AID from bony fishes (e.g., zebrafish and pufferfish) lacks a PKA phosphorylation site corresponding to S38 but still catalyzes CSR following ectopic expression in AID-deficient mouse B cells [38, 39]. These findings led some to conclude that AID phosphorylation at S38 is not likely to be of physiological relevance [38, 39, 49]. However, AID from all species of bony fish analyzed has been found to contain an aspartic acid residue at amino acid position 44 (D44) [38, 39]. Biochemical studies revealed that zAID D44 acts as a mimic of the phosphorylated mAID S38 residue with respect to RPA binding and function in the transcription-dependent dsDNA deamination assay [52]. Likewise, the integrity of the AID D44 residue is required for normal CSR; a zAIDD44A mutant shows greatly reduced CSR activity, which correlates with loss of ability to bind RPA and loss of activity in the transcription-coupled dsDNA deamination assay (Figure 2) [52].

These observations led to the hypothesis that bony fish AID represents a “constitutively active” mimic of S38 phosphorylated AID from higher organisms. Notably, increases in AID activity beyond its physiological levels seem to affect its off-target activities (e.g., initiation of translocations), more dramatically than its on-target activities (e.g., CSR and SHM of Ig genes) [55-58]. This property may have led to the evolution of precise mechanisms to titrate the level of active AID to better control its physiological activity. Such regulatory mechanisms appear to include a variety of different post-transcriptional modes of control [43, 47, 52, 58-61]. Notably, amphibians, in which CSR first evolved, as well as higher vertebrates, all express AID that appears capable of regulation via S38 phosphorylation. In this context, one speculation is that the evolution of CSR, which involves large numbers of dangerous DNA DSBs also led to the evolution of more stringent AID control mechanisms, including S38 phosphorylation.

A standard method to mimic a phosphorylated serine is to convert it to an aspartic acid. In this regard, several groups generated an AIDS38D mutant protein and found it to still be impaired with respect to promoting CSR following introduction into AID-deficient activated B cells [44], which again has been cited as evidenced that S38 phosphorylation has no physiological relevance [49]. However, any amino acid substitution might have adverse negative effects on activity via a variety of different mechanisms (so such an argument is not necessarily valid). On the other hand, if one could indeed make a relevant second site mutation that simultaneously reversed all of the negative biochemical and in vivo CSR effects of the AIDS38A mutation, it would be strong evidence in support of the proposed mechanism. Taking a clue from zAID, an aspartate residue was incorporated on the mAIDS38A polypeptide at the same relative position (in place of the threonine at residue 40) as the zAID D44 residue to generate mAIDS38A,T40D double-mutant protein [52]. Remarkably, the AID T40D mutation substantially reversed the negative biochemical effects of the S38A mutation (Figure 2). Thus, the mAIDS38A,T40D now showed ability to bind RPA constitutively and, thereby, catalyze RPA-dependent deamination of a transcribed dsDNA substrate in a PKA-phosphorylation-independent fashion. In addition, the mAIDS38A,T40D double-mutant protein had significantly increased CSR activity as compared to the AIDS38A mutant protein. These observations demonstrate that the AIDS38A,T40D protein acts like a mimic of AID phosphorylated at S38 both with respect to known biochemical activities and in vivo CSR activity (Figure 2) [52]. This linkage of the various biochemical and CSR activities with this second site mutation provides the most compelling evidence to date for the physiological relevance of AID phosphorylation at S38 and resulting RPA interaction. A remaining question, potentially of significant mechanistic interest, is why AIDS38D mutant protein does not regain CSR activity.

8. PERSPECTIVE

The clear defects in CSR and, to a lesser extent, SHM of the AIDS38A/S38A mutant mice, coupled with the generation of a “S38 phospho-mimetic” form of the mAID protein provide strong evidence in support of a significant physiological role of AID phosphorylation at S38. Likewise, these studies also strongly support the physiological significance of S38-phosphorylated AID interaction with RPA to augment AID access to transcribed target DNA sequences. Yet, there are many important unanswered questions regarding this mechanism. One major question is the precise role of S38 phosphorylation in AID regulation. The bulk of AID in activated B cells is found in the cytoplasm with only a fraction of AID being found in the nucleus [43, 62]. On the other hand, most of the S38-phosphorylated AID in activated B cells is found in the nucleus, likely in association with the chromatin fraction of cellular DNA [44]. In this context, it remains to be determined where the PKA phosphorylation of AID occurs within activated B cells and how it is regulated. In any case, PKA-phosphorylated AID may be preferentially accumulated in the nucleus, perhaps in the context of binding to target DNA via its RPA association. Likewise, the precise role for the evolution of the regulation of AID interaction with RPA via S38 phosphorylation remains to be determined. As outlined above, it appears that the pool of functionally active AID in activated B cells is quite strictly titrated. Moreover, the effect of small decreases in the level of AID that cannot be phosphorylated on S38 appear disproportionately greater than similar decreases in WT AID levels, suggesting that S38 phosphorylation might have a significant role in determining the level of “active” AID in the cells. It has been speculated that such a level of regulation may be critical to maintain the balance between on-target AID in the context of SHM and CSR versus off-target activities that could lead to mutations and/or DSBs in other cellular genes that might contribute to transformation [27, 55, 56, 63, 64]. The availability of a mutant AID that appears to behave like a “constitutively S38-phosphorylated mimetic” should now allow these notions to be addressed by gene-targeted knock-in mutational strategies that will facilitate evaluation of the effects of having all of the endogenous AID in an “activated” form.

IgH CSR appears to be dramatically impaired in AIDS38A/S38A mutant B cells. Residual IgH CSR activity (generally less than 5% of WT levels) could be provided by the R-loop mechanism for AID access. However, this raises the question of why R-loops do not provide greater access. Among the possibilities is that the S38 phosphorylation/RPA mode of AID access is important for accessing the template strand (which is hybridized to the germline transcript in a R-loop). Another would be that the RPA bound to S region DNA in the context of the AID/RPA complex has additional functions in recruitment of factors downstream of AID deamination [11, 33]. The relatively high levels of residual SHM in AIDS38A/S38A mice raises various questions. First, the SHM levels observed in AIDS38A/S38A represent steady-state levels in B cells that have likely undergone significant selection following the germinal center response in which SHM occurs. Thus, it still remains possible that the actual rate of SHM might be lower than indicated by the steady-state levels. In this regard, we note that, based on kinetics of induction, the actual rate of CSR in AIDS38A/S38A activated B cells appears much less than the steady-state levels observed in activated AIDS38A/S38A versus WT B cells following 4.5 days of induction (see above). On the other hand, there well may be additional mechanisms by which AID accesses transcribed variable region exons in the context of SHM. Studies of genetically modified yeast and DT40 cells have suggested the existence of a R-loop-related mechanism of AID access that relies on factors involved in the processing of nascent RNA transcripts and their release from the DNA template [65-67]. In addition, other potential modes of generation of ssDNA substrates, including generation of negative super-coiling of transcribed DNA, have been shown to provide AID access to DNA substrates in biochemical assays [30-32]. Clearly there is much to be done to further elucidate the mechanisms that target AID to its appropriate substrates and protect other cellular DNA sequences from its highly mutagenic activities. In this regard, none of the postulated mechanisms for AID access appear sufficient to provide the remarkable specificity of AID access to Ig gene SHM and CSR substrates versus other cellular DNA sequences.

Acknowledgments

U.B. is a fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America. J.C. is supported by grants from the Damon-Runyon Scholars Fund and the Bressler Foundation. This work was supported by NIH grant A1077595 to F.W.A. F.W.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Chaudhuri J, Alt FW. Class-switch recombination: interplay of transcription, DNA deamination and DNA repair. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:541–552. doi: 10.1038/nri1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Molecular Mechanism of Class Switch Recombination: Linkage with Somatic Hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:165–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, Forveille M, Dufourcq-Labelouse R, Gennery A, Tezcan I, Ersoy F, Kayserili H, Ugazio AG, Brousse N, Muramatsu M, Notarangelo LD, Kinoshita K, Honjo T, Fischer A, Durandy A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhuri J, Tian M, Khuong C, Chua K, Pinaud E, Alt FW. Transcription-targeted DNA deamination by the AID antibody diversification enzyme. Nature. 2003;422:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nature01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramiro AR, Stavropoulos P, Jankovic M, Nussenzweig MC. Transcription enhances AID-mediated cytidine deamination by exposing single-stranded DNA on the nontemplate strand. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:452–456. doi: 10.1038/ni920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson SK, Market E, Besmer E, Papavasiliou FN. AID Mediates Hypermutation by Deaminating Single Stranded DNA. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:1291–1296. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohail A, Klapacz J, Samaranayake M, Ullah A, Bhagwat AS. Human activation-induced cytidine deaminase causes transcription-dependent, strand-biased C to U deaminations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2990–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen-Mahrt SK, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. AID mutates E. coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature. 2002;418:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature00862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhuri J, Basu U, Zarrin A, Yan C, Franco S, Perlot T, Vuong B, Wang J, Phan RT, Datta A, Manis J, Alt FW. Evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain class switch recombination mechanism. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:157–214. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutzker S, Alt FW. Structure and expression of germ line immunoglobulin gamma 2b transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1849–1852. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1849. published erratum appears in Mol Cell Biol 1988 Oct;8(10):4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutzker S, Rothman P, Pollock R, Coffman R, Alt FW. Mitogen- and IL-4-regulated expression of germ-line Ig gamma 2b transcripts: evidence for directed heavy chain class switching. Cell. 1988;53:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuberger MS, Harris RS, Di Noia J, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Immunity through DNA deamination. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:305–312. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Noia J, Neuberger MS. Altering the pathway of immunoglobulin hypermutation by inhibiting uracil-DNA glycosylase. Nature. 2002;419:43–48. doi: 10.1038/nature00981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarrin AA, Del Vecchio C, Tseng E, Gleason M, Zarin P, Tian M, Alt FW. Antibody class switching mediated by yeast endonuclease-generated DNA breaks. Science. 2007;315:377–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1136386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan CT, Boboila C, Souza EK, Franco S, Hickernell TR, Murphy M, Gumaste S, Geyer M, Zarrin AA, Manis JP, Rajewsky K, Alt FW. IgH class switching and translocations use a robust non-classical end-joining pathway. Nature. 2007;449:478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature06020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKean D, Huppi K, Bell M, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert M. Generation of antibody diversity in the immune response of BALB/c mice to influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:3180–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YJ, Joshua DE, Williams GT, Smith CA, Gordon J, MacLennan IC. Mechanism of antigen-driven selection in germinal centres. Nature. 1989;342:929–931. doi: 10.1038/342929a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham P, Bransteitter R, Petruska J, Goodman MF. Processive AID-catalysed cytosine deamination on single-stranded DNA simulates somatic hypermutation. Nature. 2003;424:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu K, Huang FT, Lieber MR. DNA substrate length and surrounding sequence affect the activation-induced deaminase activity at cytidine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6496–6500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311616200. Epub 2003 Nov 6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beale RC, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Harris RS, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Comparison of the differential context-dependence of DNA deamination by APOBEC enzymes: correlation with mutation spectra in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarrin AA, Alt FW, Chaudhuri J, Stokes N, Kaushal D, Du Pasquier L, Tian M. An evolutionarily conserved target motif for immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ni1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue K, Rada C, Neuberger MS. The in vivo pattern of AID targeting to immunoglobulin switch regions deduced from mutation spectra in msh2-/- ung-/- mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2085–2094. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen HM, Peters A, Baron B, Zhu X, Storb U. Mutation of BCL-6 gene in normal B cells by the process of somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. Science. 1998;280:1750–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasqualucci L, Neumeister P, Goossens T, Nanjangud G, Chaganti RS, Kuppers R, Dalla-Favera R. Hypermutation of multiple proto-oncogenes in B-cell diffuse large-cell lymphomas. Nature. 2001;412:341–346. doi: 10.1038/35085588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu M, Duke JL, Richter DJ, Vinuesa CG, Goodnow CC, Kleinstein SH, Schatz DG. Two levels of protection for the B cell genome during somatic hypermutation. Nature. 2008;451:841–845. doi: 10.1038/nature06547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rada C, Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Mismatch recognition and uracil excision provide complementary paths to both Ig switching and the A/T-focused phase of somatic mutation. Mol Cell. 2004;16:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rada C, Williams GT, Nilsen H, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, Neuberger MS. Immunoglobulin Isotype Switching Is Inhibited and Somatic Hypermutation Perturbed in UNG-Deficient Mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1748–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besmer E, Market E, Papavasiliou FN. The transcription elongation complex directs activation-induced cytidine deaminase-mediated DNA deamination. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4378–4385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02375-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen HM, Ratnam S, Storb U. Targeting of the activation-induced cytosine deaminase is strongly influenced by the sequence and structure of the targeted DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10815–10821. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10815-10821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen HM, Storb U. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) can target both DNA strands when the DNA is supercoiled. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhuri J, Khuong C, Alt FW. Replication protein A interacts with AID to promote deamination of somatic hypermutation targets. Nature. 2004;430:992–998. doi: 10.1038/nature02821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian M, Alt FW. Transcription-induced cleavage of immunoglobulin switch regions by nucleotide excision repair nucleases in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24163–24172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinkura R, Tian M, Smith M, Chua K, Fujiwara Y, Alt FW. The influence of transcriptional orientation on endogenous switch region function. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:435–441. doi: 10.1038/ni918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu K, Chedin F, Hsieh CL, Wilson TE, Lieber MR. R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:442–451. doi: 10.1038/ni919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz M, Flajnik MF, Klinman N. Evolution and the molecular basis of somatic hypermutation of antigen receptor genes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:67–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakae K, Magor BG, Saunders H, Nagaoka H, Kawamura A, Kinoshita K, Honjo T, Muramatsu M. Evolution of class switch recombination function in fish activation-induced cytidine deaminase, AID. Int Immunol. 2006;18:41–47. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barreto VM, Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Zhao Y, Hammarstrom L, Misulovin Z, Nussenzweig MC. AID from bony fish catalyzes class switch recombination. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:733–738. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du Pasquier L, Robert J, Courtet M, Mussmann R. B-cell development in the amphibian Xenopus. Immunol Rev. 2000;175:201–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.2000.imr017501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flajnik MF. Comparative analyses of immunoglobulin genes: surprises and portents. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stavnezer J, Amemiya CT. Evolution of isotype switching. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:257–275. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu U, Chaudhuri J, Alpert C, Dutt S, Ranganath S, Li G, Schrum JP, Manis JP, Alt FW. The AID antibody diversification enzyme is regulated by protein kinase A phosphorylation. Nature. 2005;438:508–511. doi: 10.1038/nature04255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Barreto VM, Robbiani DF, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of hypermutation by activation-induced cytidine deaminase phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:8798–8803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603272103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Schwickert TA, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of class switch recombination and somatic mutation by AID phosphorylation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:2585–2594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasqualucci L, Kitaura Y, Gu H, Dalla-Favera R. PKA-mediated phosphorylation regulates the function of activation-induced deaminase (AID) in B cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509969103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basu U, Chaudhuri J, Phan RT, Datta A, Alt FW. Regulation of activation induced deaminase via phosphorylation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;596:129–137. doi: 10.1007/0-387-46530-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chatterji M, Unniraman S, McBride KM, Schatz DG. Role of activation-induced deaminase protein kinase A phosphorylation sites in Ig gene conversion and somatic hypermutation. J Immunol. 2007;179:5274–5280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shinkura R, Okazaki IM, Muto T, Begum NA, Honjo T. Regulation of AID function in vivo. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;596:71–81. doi: 10.1007/0-387-46530-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pham P, Smolka MB, Calabrese P, Landolph A, Zhang K, Zhou H, Goodman MF. Impact of phosphorylation and phosphorylation-null mutants on the activity and deamination specificity of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17428–17439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802121200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng H-L, Vuong B, Basu U, Franklin A, Schwer B, Phan R, Datta Manis J, Alt FW, Chaudhuri J. Integrity of Serine-38 AID phosphorylation site is critical for somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in mice. Proceeding of the national cademy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812304106. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basu U, Wang Y, Alt FW. Evolution of phosphorylation-dependent regulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Mol Cell. 2008;32:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sernandez IV, de Yebenes VG, Dorsett Y, Ramiro AR. Haploinsufficiency of activation-induced deaminase for antibody diversification and chromosome translocations both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takizawa M, Tolarova H, Li Z, Dubois W, Lim S, Callen E, Franco S, Mosaico M, Feigenbaum L, Alt FW, Nussenzweig A, Potter M, Casellas R. AID expression levels determine the extent of cMyc oncogenic translocations and the incidence of B cell tumor development. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1949–1957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramiro A, San-Martin BR, McBride K, Jankovic M, Barreto V, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. The role of activation-induced deaminase in antibody diversification and chromosome translocations. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:75–107. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramiro AR, Jankovic M, Callen E, Difilippantonio S, Chen HT, McBride KM, Eisenreich TR, Chen J, Dickins RA, Lowe SW, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. Role of genomic instability and p53 in AID-induced c-myc-Igh translocations. Nature. 2006;440:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature04495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramiro AR, Nussenzweig MC, Nussenzweig A. Switching on chromosomal translocations. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7837–7839. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teng G, Hakimpour P, Landgraf P, Rice A, Tuschl T, Casellas R, Papavasiliou FN. MicroRNA-155 is a negative regulator of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Immunity. 2008;28:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Basu U, Franklin A, Alt FW. Review. Post-translational regulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aoufouchi S, Faili A, Zober C, D’Orlando O, Weller S, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. Proteasomal degradation restricts the nuclear lifespan of AID. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1357–1368. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dorsett Y, McBride KM, Jankovic M, Gazumyan A, Thai TH, Robbiani DF, Di Virgilio M, San-Martin BR, Heidkamp G, Schwickert TA, Eisenreich T, Rajewsky K, Nussenzweig MC. MicroRNA-155 suppresses activation-induced cytidine deaminase-mediated Myc-Igh translocation. Immunity. 2008;28:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schrader CE, Linehan EK, Mochegova SN, Woodland RT, Stavnezer J. Inducible DNA breaks in Ig S regions are dependent on AID and UNG. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:561–568. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robbiani DF, Bothmer A, Callen E, Reina-San-Martin B, Dorsett Y, Difilippantonio S, Bolland DJ, Chen HT, Corcoran AE, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. AID is required for the chromosomal breaks in c-myc that lead to c-myc/IgH translocations. Cell. 2008;135:1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramiro AR, Jankovic M, Eisenreich T, Difilippantonio S, Chen-Kiang S, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. AID is required for c-myc/IgH chromosome translocations in vivo. Cell. 2004;118:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gomez-Gonzalez B, Aguilera A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase action is strongly stimulated by mutations of the THO complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8409–8414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Manley JL. Cotranscriptional processes and their influence on genome stability. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1838–1847. doi: 10.1101/gad.1438306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li X, Manley JL. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell. 2005;122:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]