Abstract

We examined the content of electronically mediated communications in a trial of shared care planning (SCP) for long-term condition management. Software supports SCP by sharing patient records and care plans among members of the multidisciplinary care team (with patient access). Our analysis focuses on a three-month period with 73 enrolled patients, 149 provider-assigned tasks, 64 clinical notes and 48 care plans with 162 plan elements. Results show that content of notes entries is often related to task assignment and that nurses are the most active users. Directions for refinement of the SCP technology are indicated, including better integration of notes, tasks and care team notifications, as well as the central role of nurses for design use cases. Broader issues are raised about workforce roles and responsibilities for SCP, integrating patient-provider and provider-provider communications, and the centrality of care plans as the key entity in mediation of the care team.

Introduction

The New Zealand National Shared Care Planning Programme (NSCPP) has been established by the National Information Technology Health Board (ITHB) to investigate approaches to implementing shared care planning (SCP) as an enabler to support long-term condition management. It is assumed in the SCP model that all stakeholders would have access to more timely and pertinent supporting information. By providing stakeholders with this shared information it will enable increased involvement in supporting a person (or self-supporting) while reducing the overall unplanned and preventable demand for health services. The evidence base for SCP activities has been reported in the United Kingdom (UK)1–3, the United States4–6, Australia7–9 and Canada10. The approach taken often emphasizes either shared care or care planning.

Shared care is “an approach to care which uses the skills and knowledge of a range of health professionals who share joint responsibility in relation to an individual’s care.”11 The concept of “shared care” has synergies with terms such as “coordinated care”, “collaborative care” and “integrated care.” Collaborative intervention using E.H. Wagner’s Chronic Care Model12, which can be seen as a type of shared care, has lowered the cardiovascular disease risk factors of patients with diabetes13. Shared care is sometimes associated with care planning. A UK Department of Health report suggests that every person with a long-term condition should have an “integrated care plan” developed and reviewed with a lead health care professional from the care team2. The Australian Flinders Program recommends a self-management care plan that is “a structured, comprehensive plan developed by the patient and their significant others, carers and health professional(s).”7

In this paper we provide an analysis of the content recorded into the software system supporting the NSCPP’s long-term condition management trial. While aspects of the analysis are quantitative, the objectives are qualitative: to understand who is using the system, for what, and through this to provide insight into barriers and opportunities to enable effective wider deployment of the IT-supported SCP.

Background

The New Zealand (NZ) healthcare system consists of primary, secondary and tertiary sectors administered by district health boards (DHBs)14. Like the UK and Australia, NZ has a strong culture of general practice medicine. General Practitioners (GPs) work as partners or employees of for-profit or charitable trust general practices, themselves aligned to Primary Healthcare Organisations (PHO). The PHOs are reimbursed by the DHBs on a capitated model for their enrolment of patients. The general practice may refer a patient for secondary care, often via the outpatient departments of public hospitals which are run directly by the DHBs and employ specialist physicians. Care of patients with chronic conditions sometimes becomes fragmented between the secondary departments and general practice, particularly if there is more than one chronic condition.

NZ enjoys a notably high level of computerization in general practice15, as well as nearly universal IT infrastructure in community pharmacy and hospitals. These systems, however, are only partially integrated. The National Health IT Plan16 is progressing their greater integration and building toward regional health data repositories that will enable services such as SCP. Metro Auckland (a combination of three DHBs) has the most matured kernel of such a repository in its regional laboratory (and now dispensing) repository, TestSafe17, and thus was a good basis for NSCPP field work.

The technology solution for NSCPP assists SCP by sharing both patient records and care plans among multiple care team members. This care team will generally include the GP and practices nurse, specialist and secondary nurse, and community pharmacist and possibly others (e.g. occupational therapist, physiotherapist or social worker). The SCP data accessible to the care team members include diagnoses, measurement results, medications, notes, record summary, care plans and task assignments (with some care plan elements being tasks). Communication may be through notes, tasks or messages. Patients can also be registered as users, although they have more limited access privileges: viewing their records rather than changing them; also patient users cannot, in the current version, assign tasks to their care team or send messages through the system to care providers. Beyond the designated care team, any authorized healthcare provider that is part of the NSCPP (but not a member of this specific care team) and hospital services in Metro Auckland can ‘break the glass’ to access a patient’s records, for instance in the Emergency Department to look up the summary page. General practice access to the tool is integrated with their practice management software. Secondary care team member and patient access is via browser.

Methods

The complex nature of shared care and the relative paucity of robust evidence of its effectiveness suggests that an interactive and iterative study protocol is appropriate to understand the impact of technology-enabled SCP on patients, health outcomes, workforce demand, funding/care models and health systems4. The NSCPP long-term condition management trial was designed to run in three phases: the “Exploration” Phase, from March to June 2011 with one participating general practice and one secondary service; the “Limited Deployment” Phase (July to December 2011), extending to eight general practices, five secondary services and four community pharmacies; and “Wide Deployment” Phase (January to June 2012). This paper focuses on the data collected up to 31 October 2011. Electronic transactional records were extracted for the period from commencement of system operation on 21 February through to 31 October 2011. This data reflects SCP activities by over 80 health care professionals and 73 patient participants with chronic conditions including heart failure, gout, COPD and diabetes.

Thematic analysis of communications records between 1 August and 31 October – including tasks descriptions (label and associated textual details), clinical notes, care plan elements and messages – is used to examine the content of SCP-related communications among care team members. This period was in the “Limited Deployment Phase” where there was a great scale-up in activity. Content was clustered by two of the authors [JW and YG].

The NSCPP pilot evaluation is part of an iterative action research approach with the software being refined in response to ongoing feedback from the evaluation, which is multi-dimensional18 and emphasizes attention to the ‘voices’ of the users19. Stakeholder perspectives are sought from interviews with 40 individual health care provider participants and three patients. In addition, 267 NSCPP project documents were reviewed along with the evaluators’ notes from attending over 40 NSCPP meetings. The focus of the present paper is on analysis of the system usage, particularly in the “Limited Deployment Phase.” Interview and document analysis findings are not integrated with the results reported here, but some findings from these sources are mentioned in the Discussion (the full evaluation report is available at http://hive.org.nz/page/resources). The evaluation protocol was approved by the Northern Y Regional Ethics Committee (Reference: NTY/11/06/058).

Results

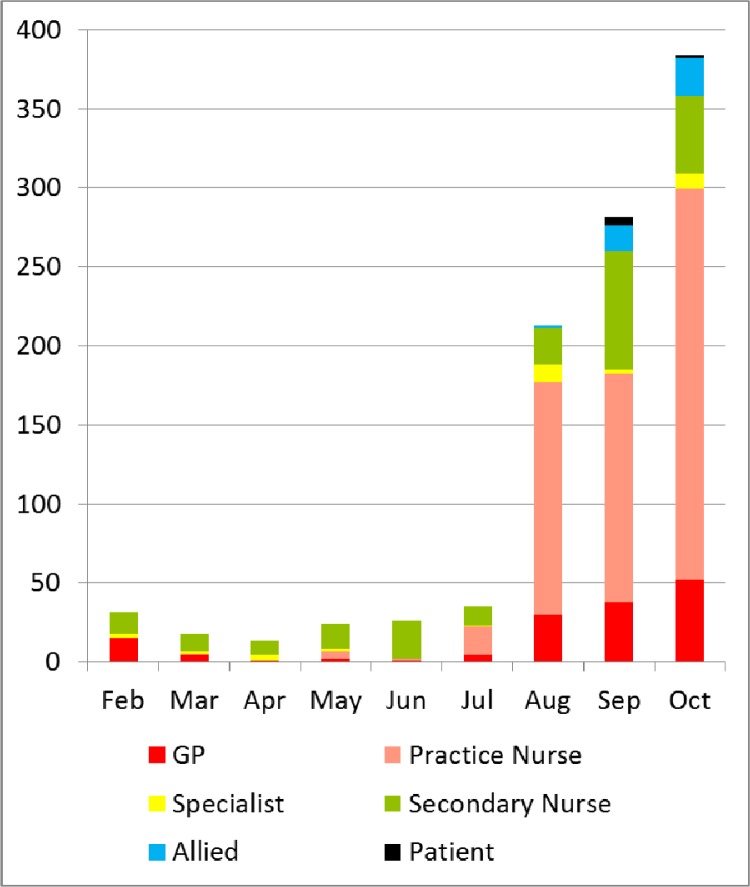

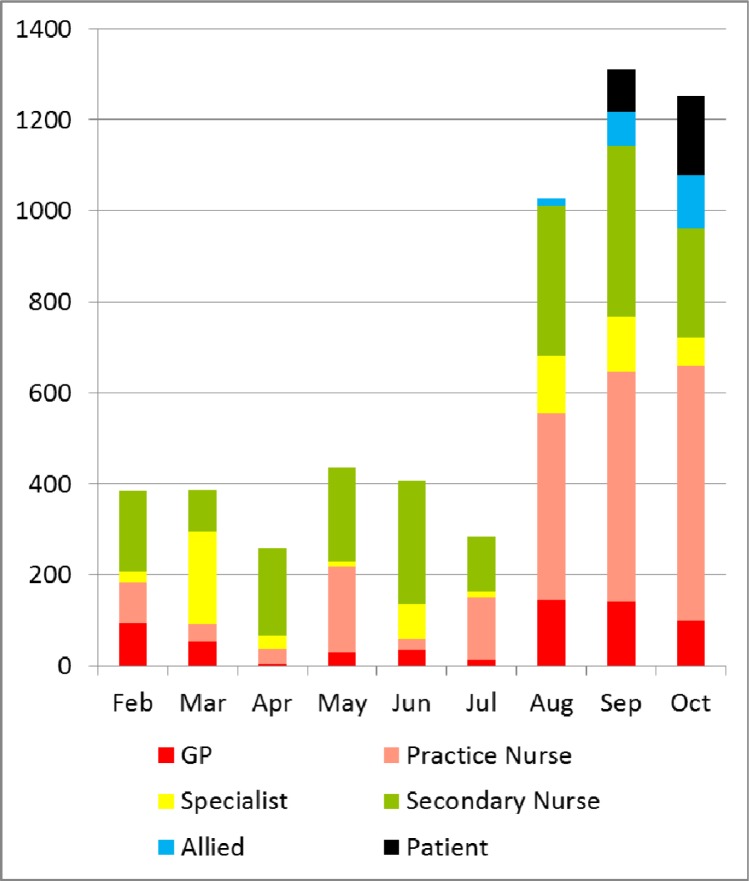

Figure 1 captures the provider/patient activities of creating and modifying tasks, notes, care plan elements and messages, by month and according to their roles – GP, general practice nurse, specialist physician, secondary nurse, allied health professional (including pharmacist and physiotherapist) and patient. The modification activity includes marking a task as completed (which is the only such action available to patients in the patient portal at the time). Figure 2 shows the provider/patient activities in terms of viewing the records, including tasks, notes, plans, messages, diagnosis, measurement results, medication and record summary, by month and roles.

Figure 1.

Sum of entries created or modified

Figure 2.

Elements viewed by user role

A number of observations can be made on the data in Figure 1 and 2, including the emergence of patient and allied users from August to October, with steady growth in allied activity and patient viewing. The role of specialist physicians as direct users, particularly with respect to element creation/modification, is quite small. The role of nurses is dominant for viewing and creation/modification on all time periods except for a few cases in the early “Exploratory Phase” in February. In “Limited Deployment Phase” (since July), the role of general practice in element creation is highly dominant (at least two-third of entries), but is more balanced by other users with respect to viewing (roughly 50%). We also see the great scale-up in activity starting in earnest in August.

Tasks

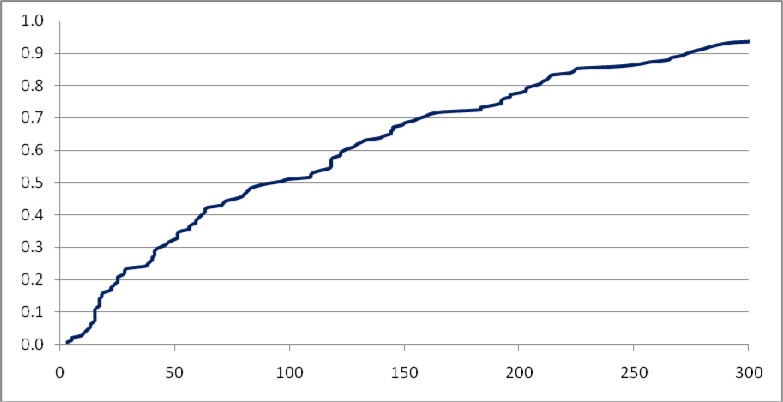

Of the 154 tasks recorded in the database as of 31 October 2011, two are recurring tasks; 106 tasks are recorded as “completed”; and 149 tasks were active on 1 August or later. These 149 tasks, with 281 relevant activities (as task creation and modification) recorded from 1 August to 31 October, were recorded as actioned by 35 individual users, including twelve secondary nurses, nine GPs, six general practice nurses, four pharmacists, two patients, one specialist and one physiotherapist. The distribution of task creation and modification activities by users is skewed to a few users. One particular user (a general practice nurse) has created 58 tasks (38.93% of all tasks) that were active during these three months; she has also undertaken 107 task modifications (38.08% of all task modification activities). Figure 3 shows the cumulative frequency distribution of the length of narrative of the tasks (including subject line and description). The median length of task text is 74 characters; the longest has 431 characters (inter-quartile range, 38 to 192).

Figure 3.

Cumulative frequency distribution of length of task text in characters (1 Aug – 31 Oct 2011)

Among the 149 tasks active on 1 August or later, 16 (10.74%) have been re-assigned to another user (including self). There are in total 35 tasks recorded as ‘assigned-to-self’ at some stage. In total, 58 users have been assigned at least one task: twelve GPs, eight general practice nurses, ten secondary nurses, one specialist, four allied health professionals (including three pharmacists and one physiotherapist), one PHO coach and 22 patients. Table 1 examines all the roles of provider/patient who use the ‘task’ feature. Table 2 shows the frequencies with which various topics were discussed in the tasks, based on a random sample of 50 tasks. Use of tasks appears to be largely in keeping with expectations for this feature, although the 10 tasks concerning activity (“what’s happening”) may be better as ‘notes.’

Table 1.

Roles of users who assign and/or being assigned tasks (1 Aug – 31 Oct 2011)

| Assign-to | GP | General Practice Nurse | Secondary Nurse | Specialist | Allied | PHO Coach | Patient | Total by Creator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task Creator | ||||||||

| GP | 6* | 2 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 38 |

| General Practice Nurse | 12 | 25* | 21 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 105 |

| Secondary Nurse | 7 | 3 | 4* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

| Specialist | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Allied | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Total by Assigned-to | 25 | 36 | 40 | 13 | 9 | 1 | 41 | 165† |

All of these tasks are assigned to self

This count includes the 16 re-assignments of 149 tasks.

Table 2.

Topics of Tasks (random 50 samples from 1 Aug to 31 Oct 2011)

| Topic | Frequency* | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up assignment | 17 | Monitoring and ordering of tests/measurements | Secondary nurse assigning a task to general practice nurse: ‘pl review pts weight and uric acid’ |

| Referral, including virtual review | GP assigning a task to secondary nurse: ‘heart racing incr CHF SOB: Please review if possible - has had episode 60mins heart racing, stable fluid status’ | ||

| Recommending further communication | GP assigning a task to secondary nurse: ‘Enrole diabetes shared care: please contact us to coordinate care’ | ||

| Care plan review | General practice nurse assigning a task to GP: ‘review care plan’ | ||

| Medication review required, sometimes with recommendations on dose change, start/stop | General practice nurse assigning a task to specialist: ‘His creatinine (228)and e GFR (27)are falling so safer to reduce allopurinol to 200 mg daily, despite good control of his urate (0.37 mmol/L)’ | ||

| Asking for or offering help for technology use | General practice nurse assigning a task to GP: ‘Hi [GP] - fixed your log on problem, blocked off some time Friday30.9.11 in am to go over it with you, and for you to add glivec to [patient]’s meds list’ | ||

| Self tasking | 12 | To record, write and review care plan | ‘Care plan for [patient]: 1. To stay well without shortness of breath & lose weight target 1 0 kg weight loss 2. To control gout and prevent it from recurring’ |

| Observations, symptoms or test result values | ‘chest xray back and no bi basal scarring’ | ||

| To change meds | ‘Stop aspirin’ | ||

| Patient review | ‘Recheck in a months time how he is going.’ | ||

| What’s happening | 10 | Medication, current dose or change | General practice nurse to specialist: ‘Have copied and pasted ‘note’ into pt notes for GP to see easily, this pt’s current dose allopurinol is 200 mg od’ |

| Patient’s NSCPP enrolment status | General practice nurse to secondary nurse: ‘Have enrolled this lady for [GP] following her discussion with you.’ | ||

| The care plan itself | General practice nurse to GP: ‘Goals: |1. Improve breathing. Breath a lot better. Walk along the beach without puffing.|2. Concerns with the amount of pills he is taking. Want to eventually cut them down….’ | ||

| Cancelled appointment | Secondary nurse to GP: ‘[Patient] was due to be seen at a clinic appt to perform spirometry today. He has cancelled this due to work commitments. He will phone again beg November to re-arrange another time.’ | ||

| Tasking patient | 8 | Exercises | ‘are you on track with the AB Doer and swimming’ |

| Promoting NSCPP | ‘Invitation to Premier showing of short movie on shared care plans’ | ||

| To write care plan | ‘can u fill out yr careplan please once u receive yr new computer’ | ||

| Communicating about care plan | ‘read the list of activities to do each weekend, check on quit smoking progress’ | ||

| Test/hello | 6 | Functionality Testing | ‘welcome, please action this task by ticking the completion box’ |

More than one topic is sometimes addressed in a single task: mean number of topics per task is 1.06 in the sample

Notes

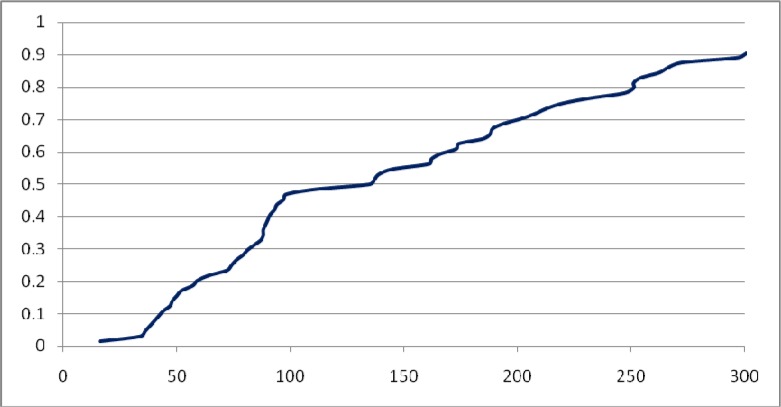

The notes field provides a general mechanism for adding text to the patient’s shared care record which all care team members can view. A note can, however, be indicated by the author as a type i.e. ‘Copy sent to GP’ (and then a notification will be sent to general practice management system to prompt about the new entry). Of the 91 notes entries in the database as of 31 October 2011, 64 were created 1 August or later and 50 of these (78.13%) are of the type ‘Copy sent to GP.’ The 64 notes were written by 20 individual users, including three GPs, five specialists, five general practice nurses, seven secondary nurses, two pharmacists and one physiotherapist. Note authorship, similar to task usage pattern, is skewed towards a few users. One user (a secondary nurse) created 20 (31.25%) of the notes, followed by one primary nurse who created 8 notes (12.5%); 65.6% of all notes were authored by six users (two secondary nurses, three general practice nurses and one specialist). The median length of notes is 135 characters (inter-quartile range, 74 to 220), see also Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cumulative frequency distribution of length of notes in characters (1 Aug 2011 – 31 Oct 2011)

Table 3 shows the frequencies of topics in the notes entries. The notes are largely the report of a home or clinic visit, including visits fundamentally related to the NSCPP enrolment process and/or care planning. The notes are frequently used as a means of communication related to assigning tasks and recommending actions for ongoing management of the patient’s condition. Notes can also be the result of actions to get into contact (e.g. results of attempts – successful or otherwise – to phone the patient) as well as intrinsic activities of technology use (e.g. noting that a user has been added). The visit notes generally include some clinical observations and care/treatment changes or actions. Many of the notes provide information related to the accuracy or currency of the medication record, often to indicate a change that has been made as the result of a visit.

Table 3.

Topics of all 64 notes created between 1 Aug and 31 Oct 2011

| Topic | Frequency* | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tasks | 40 | Intention to review | ‘will review in 2 weeks’ |

| Plans, task assignments, or recommendations on review, monitoring and ordering of tests | ‘suggested more blood glucose monitoring’ | ||

| Acknowledging task scheduled or completed | ‘Medication reviewed 29th Aug 2011.’ | ||

| Observations | 25 | Measurements taken | ‘Spirometry shows mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern’ |

| Laboratory test values | ‘His creatinine is rising 228 umol/L’ | ||

| Recent exacerbations | ‘still having some residual coughing since exacerbation of COPD 2 weeks ago’ | ||

| Reported symptoms | ‘son rang today, Mum breathing much better’ | ||

| Medications | 18 | Dose change | ‘I have increased metoprolol to 142.5mgs’ |

| Medication stopped, started, restarted | ‘re started diltiazem 12omg once daily’ | ||

| Correcting medication record | ‘Please change on meds list.her metformin she takes 2 tabs mane, i asked her to take 1 bd as prescribed until reviewed by diabetes team.’ | ||

| Administration† | 9 | Noting patient enrolled | ‘Enrolled in Shared Care today’ |

| Addition of users to care team | ‘Added [pharmacy staff member] to patients care team’ | ||

| Care plan done (or delayed) | ‘Hi [general practice nurse], Great start to care plan. I have made a few changes. feel free to add more when you see [Patient] again’ | ||

| Referrals | 5 | Plan to formally refer to service | ‘can you please fax thru referral’ |

| Patient Contact | 4 | Attempts to call patient (successful or not) | ‘I have made several calls and left messages to get in touch with [Patient] but no success’ |

| Admissions | 2 | Note of hospital or hospice admission | ‘admitted acutely to Hospice for symptom control’ |

| Test/hello | 1 | Functionality Testing | ‘Hi [general practice nurse] testing’ |

More than one topic is sometimes addressed in a single note: mean of the number of topics per note is 1.625

We grouped communications about care plan coordination in this category (five cases); alternatively, these could be seen as ‘tasks.’ We grouped them in this category as conducting a care plan is an inherent part of the NSCPP protocol.

Care Plans

Among the 73 patients enrolled in NSCPP by 31 October, 48 patients have 49 care plans created (a process undertaken in a session between the patient and a care team member). More than half of these plans (30, 61%) are entered by general practice nurses, followed by GPs (9, 18%), secondary nurses (8, 16%) and allied health professionals (including pharmacists and physiotherapists with 2 plans recorded, 4%). One GP and one physiotherapist appear to be working on developing care plans for the same patient demonstrating that a full range of provider roles can contribute to a patient’s plans. Of the 549 plan elements (detailed items in the 48 patients’ care plans), 508 were created 1 Aug or later (the core of the “Limited Deployment Phase”) for 43 patients. More than half of these entries (319) are leftover (incomplete) elements from the plan templates offered to the users by the tool such as “My main priority is.” A further 27 entries are identified as duplicates; therefore and thus omitted from the content analysis. Table 4 shows the frequencies of topics discussed in the care plans based on content analysis of a random sample of 50 records of care plan elements out of the remaining 162 entries. The frequency counts in these categories are based on a synthesis of user-chosen types and the themes identified by the researchers as emerging from the content.

Table 4.

Topics of plan elements (random 50 samples 1 Aug – 31 Oct 2011)

| Type/Topic | Frequency | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action* | 23 | Exercise | ‘walk 3 times a week for 20 – 30 mins with wife’ |

| Diet | ‘don’t eat too much pork or mussels, red meat’ | ||

| To take medication | ‘Takes warfarin regularly as prescribed’ | ||

| To take measurement | ‘Weigh daily and recognise if weight going up it means I am holding on to fluid and I need to contact GP/ Nurse or HF [heart failure] nurse’ | ||

| To make plans | ‘write down small list goals for each week’ | ||

| Smoke cessation | ‘create list of why I like smoking, why want to stop,’ | ||

| Humour | ‘get in touch with NASA via [general practice nurse] and her pt’ | ||

| Problem* | 20 | Condition | ‘to continue long term management of his heart failure’ |

| Observation/symptom | ‘I get short of breath and I can’t do anything and I become uncomfortable, angry and upset.’ | ||

| Overweight | ‘loose big stomach’ | ||

| Medication to stop in the future | ‘currently taking allopurinol’ | ||

| Personal | ‘I am bored in the weekends’ | ||

| Humour | ‘can’t get to the moon’ | ||

| Goal* | 11 | Health goals | ‘being able in 9 months time to walk 800meters to bus stop’ |

| Weight control | ‘reducing my thick waist’ | ||

| Stop certain medication | ‘come off allopurinol’ | ||

| Humour | ‘land on the moon’ | ||

| Patient/Family Knowledge | 6 | What measurements (or lab test results) mean | ‘Check sugars three times a day for a week. To be able to review insulin dose and see where sugars are high or lower’ |

| How to relieve symptoms | ‘Check that not breath holding, use puffers first, pace activity’ | ||

| How to use inhaler | ‘Needs to use spacer and wait between puffs’ | ||

| To encourage patient to use guidance booklet | ‘follow self mgmt guidance - A5 sheet, folder’ | ||

| To educate family | ‘good support but know only a little about disease encourage to ensure they are more informed’ | ||

| Task reminder | 4 | To review patient (or medications) | ‘If no improvement next week after b12 injection to have review with DR’ |

| Communication | ‘Phone check with daughter’ |

Users of the NSCPP tool can choose these types on the plan template drop-down menu.

Messages

There were 78 messages sent in total before the feature was disabled. Messages were used moderately frequently up to that time by five users (four of which were involved since February). Their content appeared frequently redundant with tasks and notes. For example, a secondary nurse created a note on medication adjustment then sent this information via a message to the GP. Based on user feedback, the message feature was disabled in late August.

Discussion

Usage analysis has revealed a number of informative patterns. Firstly, it is notable that nurses (secondary and primary care) are the most active users, particularly in terms of creating (as compared to viewing) content in the SCP database. This even extends to task assignment, an indicator of who’s ‘driving.’ However, user interviews indicated that this may underestimate the guidance provided by physicians (indeed at times even literally looking over the shoulder of the nurse operating the software). And of course the technology does not capture verbal communications that occur between nurses and physicians onsite. Nonetheless, the data suggest a major role for nurses as NSCPP moves ahead.

In terms of thematic analysis, the preponderance of task-oriented communications among the notes entries, along with the decision to shut down the message entry function, suggests a need for a degree of user interface re-design. With this re-design come opportunities to reformulate the interaction around key use cases. Already functionality has been modified to allow notes to be flagged for GP attention. One path ahead may to further integrate notes, tasks and message as a single user interface entity with options to identify task assignment and care team members for specific notification. A further interaction problem is revealed by the presence of many incomplete care plan fragment elements in the database. User interviews and focus groups revealed lack of satisfaction with the care planning user interface. Moreover, some of this dis-satisfaction may relate to a lack of fit of care planning with current care delivery activities. In any event, due to their high level of usage, nurses are key candidates to serve as central users in use case driven re-design.

The usage patterns can be further characterized by the dominance of a few lead users. On one hand, the pattern suggests the natural emergence of a few, particularly nurses, taking dominant roles in shared care activity. On the other hand, this can be taken to indicate that technology use is still not matured in terms of uptake (leaving open the possibility that usability per se is poor, or that a larger issue is presenting a barrier, such as the lack of a clear business case for investing time in shared care planning). There is some recent evidence for improved patient experience by introducing a leading role in chronic care such as community-based care coordinators in childhood asthma care20 and nurse navigators in cancer care21. There is exciting potential for workforce transformation with SCP, but with the related challenge of defining the new responsibilities (and determining if these are met by new people or reorientation of existing roles). For the present trial, the question of who funds the time to create care plans has been raised repeatedly. A designated – and appropriately compensated – lead care coordinator (perhaps a nurse), would facilitate solution of a further problem regarding the need to ensure timely responsiveness to issues emerging in the SCP record.

The present conservative approach to the patient-as-user role is based on concern that no-one in the care team is specifically responsible to respond to a patient’s online message in a timely fashion. There is a need to carefully work through the workflows and protocols for these interactions, for example, to manage expectations and understand legal and ethical implications. With respect to present technology, the general practice systems provide ‘inbox’ mechanisms used for laboratory test reports and electronic discharge summaries that help to facilitate notification; but the best mechanism is less clear on the hospital side, with a mix of more formal processes (e.g. referrals) and informal modes (e.g. personal e-mail), neither of which suit this new interaction modality.

The content analysis suggests a potential dichotomy of patient-provider and provider-provider communications. It is a tenant of Wagner’s model12 that the patient should be ‘activated’ and a requirement of the Flinders Model7 to systematically elicit and track problems and goals in the patient’s own terms. As such, the development of a care plan based on a face-to-face session with the patient appears to be a minimum requirement. Development of clearer protocols and associated functionality for more direct patient engagement (e.g. patient online questions) is identified as a priority for the next phase of NSCPP. With this said, the other side of Wagner’s model is the “prepared, proactive care team”. The value of a tool that could fuse our present system of un-integrated providers into such a team should not be underestimated. A great proportion of the communications may continue to be amongst the professional care team members, particularly for patients with complex clinical needs. In relation to this, the language of the care plan elements appears approachable to a wide range of patients (unsurprisingly, since the patients participated in the care planning sessions). Conversely, the notes and some of the tasks contain many dense segments regarding observations and medications, often rich in acronyms. While not generally harmful for the patient to see, they are also not generally comprehensible for the patient. The difference in language suggests that notes intended to facilitate communication amongst providers might usefully be presented differently in the user interface, particularly the patient user interface, than care plan problems and goals and patient-initiated messages.

There is a question as to how central the care plan itself is as the key artifact in SCP. There is great potential benefit in shared discourse amongst clinical users around relatively narrow clinical matters, particularly medication issues. Such discourse centers on a complete medication record and supporting laboratory test results, clinical observations and related notes. It often involves a narrow, tactical treatment plan such as to titrate a dose dependent on a test result value. This is valuable ‘shared care’ – and could usefully involve the patient directly in terms of reporting side effects or measurements they take at home. But it may be awkward to force this activity into the structure of a hierarchical care plan stemming from a care planning session with the patient. On the other hand, the more that SCP interaction occurs outside of the patient-centered care plan, the more the care plan (and thus patient problems and goals) is marginalized. If care planning is to be meaningful, the software interface and protocols should encourage easy integration of plan elements with clinical management and treatment tasks, but should also allow good management of a clinical conversation that emerges outside of the care planning cycle.

The NSCPP evaluation has a number of inherent limitations. Most notably, there is no basis for direct measurement of SCP contribution to outcomes such as improved health status or cost benefits. The recruitment method opted for: (a) providers that are volunteers and likely to be a biased representation of the provider population; and (b) patients selected by the providers with biases both in terms of their need for SCP and their appropriateness for such management. While these limitations could have been addressed by randomization, participants are of course not blind to the fact that they are participating in a trial of SCP and using novel IT. In the long run, if a region is saturated with use of SCP it would be feasible to compare the outcome of specific patient cohorts in that region to the same region at an earlier time and/or to other regions, controlling for patient and provider variables. In the near term, the most accessible measures are related to the process of care – engagement of clinicians across organizational boundaries in online conversations about patient care tasks and management is a good sign that the program is creating a communications medium amenable to the promotion of timely and evidence based care.

Conclusion

We have observed IT facilitating shared care planning activities by sharing both patient records and planned care activity among care team members. The team members across the primary-secondary boundary have communicated with one and another as well as with the patient to coordinate care through task assignments, notes, care plans, and messages between users. The results indicate directions for ongoing refinement of the SCP technology. There appears to be potential for a closer linkage of notes, tasks and assignment of care team recipients to receive notifications to allow clearer interaction pathways and less redundant data entry. Also striking is the central role of nurses for re-design use cases based on their dominance as creators of database content. The trial also raises a broader issue about appropriate workforce roles and responsibilities for SCP, how patient-provider communication integrates with provider-provider communication, and the centrality of care plans as the key entity in IT-mediation of a care team. The need to understand the best funding models is also evident from the trial outcomes and will be a significant lever in the scaling-up process.

The NSCPP long-term condition management trial has moved into a Wide Deployment stage, engaging a larger user base across the Auckland metro area. Refinement of the software functionality and user interface is continuing, as is the dialogue concerning appropriate user roles, responsibilities and compensation.

Acknowledgments

The evaluation study was funded by the New Zealand national IT Health Board. We extend our thanks to all the users, project team members and software vendor staff for accommodating our study.

References

- 1.Fulop N, Mowlem A, Edwards N. Building Integrated Care: Lessons from the UK and elsewhere. London: The NHS Confederation; 2005. [updated 2005; cited 2011 Mar 15]; Available from: http://www.nhsconfed.org/Publications/Documents/Building%20integrated%20care.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UK Department of Health Impact assessment for implementing personalised care planning for people with long-term conditions (including guidance to NHS and social care) 2009. [updated 2009; cited 2011 Mar 14]; Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_098503.pdf.

- 3.Lewis RQ, Rosen R, Goodwin N, Dixon J. Where next for integrated care organisations in the English NHS? : Nuffield Trust. 2010. [updated 2010; cited 2011 Mar 15]; Available from: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/members/download.aspx?f=%2Fecomm%2Ffiles%2FWhere_next_ICO_KF_NT_230310.pdf&a=skip.

- 4.Crabtree BF, Chase SM, Wise CG, Schiff GD, Schmidt LA, Goyzueta JR, et al. Evaluation of patient centered medical home practice transformation initiatives. Med Care. 2010 Jan;49(1):10–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f80766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaen CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, Palmer RF, Wood R, Davila M, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S57–67. S92. doi: 10.1370/afm.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Yu O, Ross TR, Tufano JT, Soman MP, et al. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009 Sep;15(9):e71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Battersby M, Harvey P, Mills PD, Kalucy E, Pols RG, Frith PA, et al. SA HealthPlus: a controlled trial of a statewide application of a generic model of chronic illness care. Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):37–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battersby M, Von Korff M, Schaefer J, Davis C, Ludman E, Greene SM, et al. Twelve evidence-based principles for implementing self-management support in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011 Dec;36(12):561–70. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preen DB, Bailey BE, Wright A, Kendall P, Phillips M, Hung J, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary, post-discharge continuance of care intervention on quality of life, discharge satisfaction, and hospital length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005 Feb;17(1):43–51. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomik TA. A report on shared care (Part of the Primary Health Shared Care Network Development Initiative), 2005, Provincial Health Services Authority. 2005. [updated 2005; cited 2011 Mar 14]; Available from: http://www.phsa.ca/NR/rdonlyres/6A84F609-CCAA-40DC-BD62-B2FAC7BE2356/0/SharedCareReport2005.pdf.

- 11.Moorhead R. Sharing care between allied health professional and general practitioners. Aust Fam Physician. 1995 Nov;24(11):1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vargas RB, Mangione CM, Asch S, Keesey J, Rosen M, Schonlau M, et al. Can a chronic care model collaborative reduce heart disease risk in patients with diabetes? J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Feb;22(2):215–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0072-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health . Overview of the health system. Wellington: 2011. [updated 2011 March 19; cited 2012 Feb 29]; Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/overview-health-system. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squires D, Peugh J, Applebaum S. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 Nov-Dec;28(6):w1171–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Health IT Board . National Health IT Plan: Enabling an integrated healthcare model. Wellington: 2010. Sep, ( http://www.ithealthboard.health.nz/content/national-health-it-plan) Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 17.healthAlliance . CareConnect: TestSafe. Auckland: 2012. [updated 2012; cited 2012 March 02]; Available from: http://www.testsafe.co.nz/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J, Georgiou A, Ampt A, Creswick N, Coiera E, et al. Multimethod evaluation of information and communication technologies in health in the context of wicked problems and sociotechnical theory. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007 Nov-Dec;14(6):746–55. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T, Russell J. Why do evaluations of eHealth programs fail? An alternative set of guiding principles. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Findley S, Rosenthal M, Bryant-Stephens T, Damitz M, Lara M, Mansfield C, et al. Community-based care coordination: practical applications for childhood asthma. Health Promot Pract. 2011 Nov;12(6 Suppl 1):52S–62S. doi: 10.1177/1524839911404231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thygesen MK, Pedersen BD, Kragstrup J, Wagner L, Mogensen O. Benefits and challenges perceived by patients with cancer when offered a nurse navigator. Int J Integr Care. 2011 Oct;11:e130. doi: 10.5334/ijic.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]