Abstract

We present and test the intuition that letters to the editor in journals carry early signals of adverse drug events (ADEs). Surprisingly these letters have not yet been exploited for automatic ADE detection unlike for example, clinical records and PubMed. Part of the challenge is that it is not easy to access the full-text of letters (for the most part these do not appear in PubMed). Also letters are likely underrated in comparison with full articles. Besides demonstrating that this intuition holds we contribute techniques for post market drug surveillance. Specifically, we test an automatic approach for ADE detection from letters using off-the-shelf machine learning tools. We also involve natural language processing for feature definitions. Overall we achieve high accuracy in our experiments and our method also works well on a second new test set. Our results encourage us to further pursue this line of research.

INTRODUCTION

Recognizing adverse drug events as early as possible and disseminating information about such effects are critical for the welfare of the public. Post-marketing surveillance systems such as the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) serve an important function as they allow health professionals and consumers to report adverse events. However, such post-marketing surveillance is passive. Thus there is keen interest in automatically detecting such events from other sources and thereby reducing the time delay between initial release of a drug to the finding of an adverse effect. Currently, researchers are detecting adverse events from DrugBank database1, PubMed searches2, narrative discharge summaries in electronic medical records3, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System VAERS4, etc. For example Botsis et al.4 found that multi-level text mining for automated classification of VAERS reports could potentially reduce human workload for finding ADEs. In another study, Aramaki et al.5 used a pattern-based method and Support Vector Machine (SVM) based method to examine patients’ clinical records. They used ‘word chain’ features (examining the words between the symptom and the drug name) and obtained encouraging results. Surprisingly one information source that has yet to be explored is that of Letters to the Editor (LtE) in medical journals. We suggest that LtE are also an important resource of ADE information.

There are three possible reasons why LtEs have been ignored for automatic ADE detection. The first is that LtEs almost never have abstracts; they are in effect extended abstracts themselves, usually no more than 1,000 words on average. In the total number of 101,832 LtEs we collected that were related to Adverse Effects, only 1,273 had an abstract (Information provided by PubMed). Thus LtEs are less likely to be retrieved when compared to other types of indexed items that do contain abstracts. Second, even when found, LtEs are less likely to be read as one has to access the online or print version of the journal in order to read any information other than just the title. Third, LtEs are more likely to represent individual observations or ‘cases’ and less likely to report results from a formal study of a drug such as a prospective study. It is more natural to report such results in formal full-sized journal publications. However, from our perspective, the observational- or case-study-based drug alerts raised in LtEs are important and in this sense seem analogous to the voluntary reports made by health professionals and consumers in the MedWatch section of the FDA’s AERS. Just as MedWatch serves an important role in monitoring drugs, so could LtEs that contain key early evidence of an adverse effect. Thus our goal is to explore the role of LtEs as an early indicator of ADEs; this class of publications has not yet been studied in this context. Indeed, LtEs may be one of the earliest publications reporting ADEs.

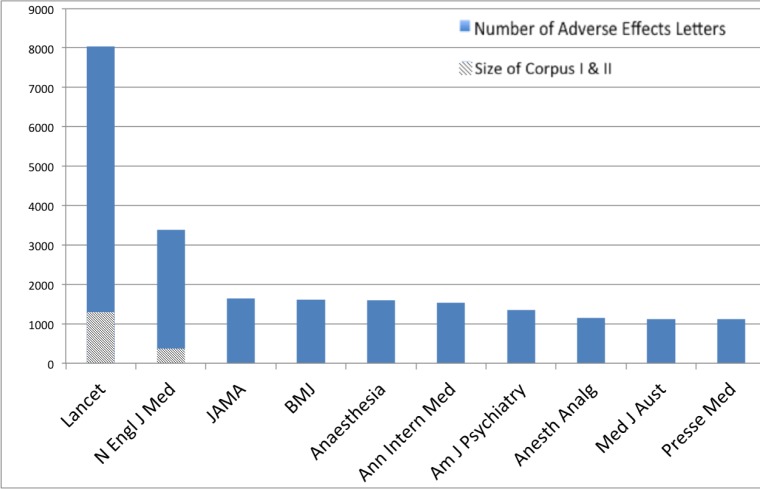

In preliminary research, published only as a one-page abstract6, we explored LtEs with a list of the 179 most commonly used drugs in 2008. This was compiled based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. We then used Micromedex1, a commercial drug information service, to find the ADEs listed for these drugs and their key publications. The number of drug-ADE pairs we obtained through this process for our 179 drugs was 8,521. Independent of these drugs, we conducted a PubMed search to retrieve LtEs reporting on adverse events. In particular we ran the PubMed search specifying ‘adverse effects’ as the MeSH term AND ‘letter’ as the PubType. (MeSH stands for Medical Subject Headings, and these terms are determined by human annotators.) A total of 101,832 LtEs were returned by the search. The LtEs spanned 2,400 sources. 1,273 had abstract and the remaining 100,559 did not. Because almost all the LtEs retrieved had no full text, next we retrieved their full-text from the respective journals. We limited the LtEs to those in The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) because these two journals have the most LtEs (The Lancet has 8,032 LtEs (7.89% of the total number) from 1967 to date, and NEJM has 3,384 LtEs (3.32% of the total number) from 1966 to date). Figure 1 shows the number of LtEs in the top 10 journals with the most LtEs referring to adverse effects. Finally we eliminated the LtEs with the label of ‘Comment’ to avoid searching LtEs specifically referencing a previously published paper. We refer to the resulting set of LtEs as our final corpus. In order to emphasize the importance of the full text, we also used the collection of LtEs without full text (i.e., LtE has just a title and MeSH) and referred to this as Corpus I. The same set of LtEs with full text, we referred to as Corpus II. The resulting dataset contained 1,290 LtEs for The Lancet and 374 for NEJM. The figure also indicates the final size of datasets Corpus I and Corpus II used in our research.

Figure 1:

Distribution of Number of LtE in Journals

We then used a heuristic to find the LtEs that matched at least one of the 8,521 drug-ADE pairs of interest in either corpus. For example: given drug D and its known ADE A, we search for D in the Substance field of the LtE. If the LtE MeSH or Full text has A in it, especially if the sentence containing A has no negation, we claim this LtE has drug D-ADE A pair in it. We found 23 LtEs in Corpus I (without full text) satisfying this criteria and 48 LtEs in Corpus II (with full text) satisfying it. All the 23 LtEs in Corpus I are subset of 48 LtEs in Corpus II. An important point to observe is that moreover all of these LtEs had publication dates that were earlier than the reported date in Micromedex for the corresponding drug-ADE pairs. The findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Drug/ADE pairs in LtEs

| Corpus I Title/MeSH | Corpus II Title/MeSH/Full-text | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Dataset size (# of LtEs) | 1,664 | 1,664 |

| # of drug-ADE pairs suggested using our heuristics | 23 | 77 |

| # of distinct drug-ADE pairs suggested using our heuristics | 10 | 35 |

| # of correct drug-ADE pairs suggested using our heuristics | 3 | 19 |

| # of LtEs matching at least one of 8,521 known drug-ADE pairs (set A) | 23 | 48 |

| Average #years prior to the year cited by Micromedex for set A | 5.29 | 6.901 |

| Min # years prior to the year cited by Micromedex for set A | 1.29 | 0.16 |

| Max # years prior to the year cited by Micromedex for set A | 17.65 | 16.22 |

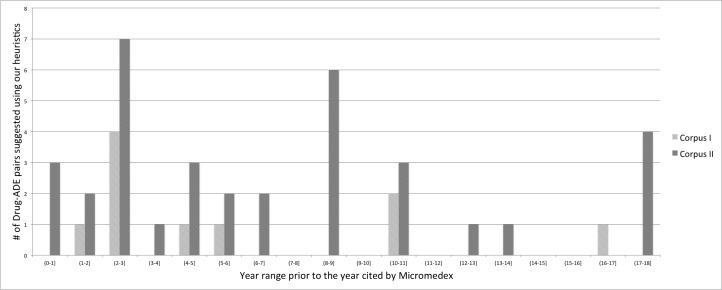

A follow up manual evaluation of the drug-ADEs pairs shows that 7 of the 10 distinct drug-ADE pairs found using Corpus I are incorrect (70% false positive rate): the LtE did not actually contain information about the specific drug-ADE pair. One of the most common mistakes of our heuristics is illustrated by this example: “A 22-year-old man with a history of malignant hypertension was given methylprednisolone on the same protocol, and towards the end of the infusion episodes of supraventricular tachycardia developed which were effectively treated.” Our heuristics mistakenly detects hypertension as the ADE of methylprednisolone. In the 35 distinct drug-ADE pairs found using Corpus II, 16 pairs are wrong. In this case, the false positive rate is 45.7%. Despite these errors, if we limit the analysis to just the pairs that were correctly identified in LtEs we find that all of them appear before their reporting in Micromedex. Also their average, minimum and maximum time prior to entry in Micromedex is 6.90, 0.16 and 16.22 years respectively using full text of LtEs. Detail of years prior to Micromedex appearance shown in Figure 2. These results demonstrate that examining the full text of LtEs is important. The results also demonstrate that LtEs do contain important and early signals of adverse drug effects.

Figure 2:

# Drug-ADE pairs: distribution of # years prior to Micromedex appearance

Although our preliminary work shows that LtEs carry early and important signals of adverse drug effects, the challenge of building a real-time post-marketing surveillance system via LtEs remains. LtEs have an unstructured format, unlike electronic health records (EHR) that contain many structured fields in addition to their unstructured ones; LtEs are narratives exhibiting linguistic sophistication and variations as in any other class of health-related articles. Manual examination of drug-ADE pairs in every LtE is time consuming, highly challenging, and certainly not a scalable strategy. Thus in order to continue our exploration of LtEs as a source for ADE detection, our goal in this paper is to adopt machine learning methods involving natural language processing (NLP) tool in the detection process.

METHODS

Architecture of Approach

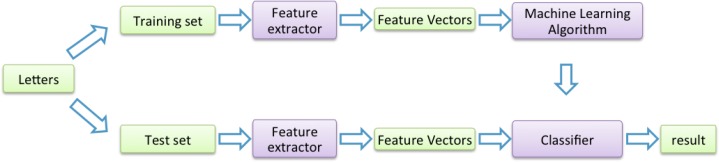

Figure 3 shows a flowchart of our classifier-based approach. We use the NLP tool MetaMap to tag the syntax label and semantic type for each word, and select two kinds of features, namely statistical features and n-gram features to build a classifier. Statistical features focus on the location of the candidate ADE term in the text and its co-occurrence with the drug. n-gram is a contiguous sequence of n items from the text. Both of them will be discussed in detail in the later sections. The goal of the binary classifier is to determine whether the candidate ADE IS or IS NOT an ADE of a drug.

Figure 3:

The Flow Chart for Training & Test Using Classifiers

Each instance in our data is a triplet of the form: <drug-candidate ADE pair, letter text, label>. Labels are True and False. ‘True’ for instance, indicates that the LtE does contain evidence that the drug is responsible for the ADE. We blank out the labels for the instances in our test set. We generate a feature vector for each instance. Then we test different machine learning algorithms to train the classifier which is then used to automatically label the test data. Finally we evaluate the test result using measures of accuracy, precision and recall, F-measure, ROC, etc.

EXPERIMENTS

Dataset

Our datasets are two subsets of Corpus II (1664 LtEs) from our preliminary research. All the LtEs are from The Lancet and NEJM and in full-text. First we create an ‘Initial Dataset’ of 48 LtEs that match at least one of the known drug-ADE pairs found using our heuristics. We also create a second ‘New Test Set’ with 20 randomly sampled LtEs from Corpus II that are not in ‘Initial Dataset’. We manually analyzed every drug-candidate ADE evidence in each LtE of these two datasets.

Because of the manual analysis we know which drug-ADE pairs are supported by each LtE. We then generate all possible triplet instances from this dataset. Specifically, we use the drug in the Substance field of LtE as our target drug and combine it with every candidate ADE we extract from the LtE. Candidate ADEs are identified using MetaMap2 with default settings. (candidate ADEs include semantic types dsyn, fndg, sosy and patf, based on the fact we found they are the top 4 most frequent semantic types in our Initial Dataset, details are given in Table 2) We didn’t limited the semantic types for target drug, the target drugs are selected from Substance field of LtE.

Table 2:

Most Frequent Drug and ADE’s Semantic Types In Intitial Dataset

| Candidate ADE | Drug |

|---|---|

|

| |

| dsyn: Disease or Syndrome | orch & phsu: Organic Chemical & Pharmacologic Substance |

| fndg: Finding | aapp & phsu: Amino Acid, Peptide, or Protei & Pharmacologic Substance |

| sosy: Sign or Symptom | phsu & strd: Pharmacologic Substance & Steroid |

| patf: Pathologic Function | antb & orch: Antibiotic & Organic Chemical |

This process yields our set of <drug-candidate ADE, letter text, label> instances for our dataset. MetaMap is a NLP tool developed by the National Library of Medicine (NLM). It is used to map biomedical text to concepts in the UMLS Metathesaurus. Note that, through our manual labeling process, we know the label for each instance of our dataset. Note too that we did not try to balance the true-false label ratio, because in a new test set the ratio could be similarly skewed. Table 3, column 2, shows some statistics of this dataset.

Table 3:

Dataset Statistics

| Initial Dataset | New Test Set | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| # letters | 48 | 20 |

| # triples | 315 | 88 |

| # true triples | 118 | 36 |

| # false triples | 197 | 52 |

| Average # of triples per letter | 6.6 | 4.4 |

Data Preprocessing

One of the challenges of automatic detection of ADEs is that the LtE text is highly narrative and has little to no predictable structure, so it is hard to develop algorithms to identify words representing drugs and those representing ADEs, not to mention identifying drug - ADE relationships. In order to find out the semantic meaning of words, we use MetaMap to process each LtE text. This gives us the label for each word in the LtE. Because MetaMap does not tag numbers, we use regular expressions to tag the numbers and then output the tagged text. The output of one of the tagged sentence in our corpus is like this:

6112549_0|0|thrombocytopeniadsyn causedverb byprep furosemideorch;phsu-inducedftcn plateletnoun antibodyaapp;imft.

Some of the semantic tags meaning are shown in Table 2. The full list of semantic type mapping can be downloaded from http://metamap.nlm.nih.gov/SemanticTypeMappings_2011AA.txt.

This tagged sentence has three parts divided by ‘|’, the first one is 6112549_0 which means the sentence is from a LtE that has a PubMed id of 6112549, and the number after the underscore refers to the nth sentence in this LtE, 0 means the title. In the second part, 0 is the negation count of the sentence provided by MetaMap NegEx3. The third part is the body of the sentence, and each word has been tagged by the semantic type or syntactic category. In this example, we know that thrombocytopenia is a candidate ADE, and furosemide is a drug. With these tagged words, we are able to generate our triplet instances (as described previous) and to generate features for our machine learning algorithms to classify the relationship between the drug and the candidate ADE.

Feature Definition

Feature definition is very important for classification. For each triplet instance in the datasets, we use two kinds of features (statistical features and n-gram features) to generate a feature vector. Statistical features shown in Table 4.

Table 4:

Statistical Features for Classification

| Type | Description | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | Boolean | Are both drug and candidate ADE in the title? |

| 2 | Boolean | Is candidate ADE in the title, while the drug is not? |

| 3 | Boolean | Are both drug and candidate ADE in the MeSH field? |

| 4 | Boolean | Is candidate ADE in the MeSH, while the drug is not? |

| 5 | Numerical | # times the candidate ADE appears in the letter |

| 6 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the same sentence |

| 7 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the first three sentences |

| 8 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the first three sentences, but drug does not |

| 9 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the first part of letter |

| 10 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the first part of letter, but drug does not |

| 11 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the second part of letter |

| 12 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the second part of letter, but drug does not |

| 13 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the third part of letter |

| 14 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the third part of letter, but drug does not |

| 15 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the fourth part of letter |

| 16 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the fourth part of letter, but drug does not |

| 17 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the fifth part of letter |

| 18 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the fifth part of letter, but drug does not |

| 19 | Numerical | # times both drug and candidate ADE appear in the last six sentences |

| 20 | Numerical | # times candidate ADE appears in the last six sentences, but drug does not |

| 21 | Numerical | the smallest word distance between the drug and candidate ADE |

| 22 | Numerical | # drug appearances in a sentence next to one containing candidate ADE |

| 23 | Numerical | # drug appearances two sentences away from sentence with candidate ADE |

| 24 | Numerical | # drug appearances three sentences away from sentence with candidate ADE |

The ‘part’ of letter in features 9–18 means the letter text is divided into five parts. For example: if the LtE has 10 sentences, the first part of the LtE means the combination of 1st and 2nd sentences. The reason why we use features 7, 8, 19, 20 is that usually the first three sentences and last three sentences are the most important (according to our manual examination of the LtEs). But in our corpus, LtEs may end with the author name, affiliation, and date. So we extend the last three sentences to last six sentences, and then do the feature selection.

Another kind of feature is the n-gram. It is popular in text mining and NLP research. In our case, n-grams could preserve the hidden patterns of the relationship between the drug and its candidate ADEs. Our n-grams are built from a combination of words and categories. Before generating n-grams from a sentence, we generalize certain words (concepts) by using dummy strings to replace the target drug, candidate ADE term and replace other drug, disease or symptom terms with different dummy strings. We want to select features using the generalized sentences.

For example, given a tagged sentence as follows:

Inprep 1970numb furosemideorch;phsu wasauxreportedhlca toadv causecnce thrombocytopeniadsyn inprep 26numb% ofprep patientsnoun butconj theypron maymodal haveaux hadaux hypersplenismdsyn secondaryqnco toadv thedet heart failuredsyn forprep whichpron thedet drugphsu wasaux prescribedhlca.

If the drug-candidate ADE pair is furosemide-thrombocytopenia, then before generating n-grams, we generalize the sentence to:

In <numb> <drug> was reported to cause <candidate ade> in <numb> % of patients but they may have had <dsyn> secondary to the <dsyn> for which the drug was prescribed.

Notice that we replace the drug name with <drug> , and candidate ADE name with <candidate ade> to preserve the pattern, and we also preserved <numb> and <dsyn> in this example.

Finally, we extract n-grams from all sentences which contain drug-candidate ADE pair. For the example above, some n-grams (separated by ‘;’) are:

unigram: in; <numb> ; <drug> ; was; reported; to; cause ...

bigram: in <numb> ; <numb> <drug> ; <drug> was; was reported; reported to ...

3-gram: in <numb> <drug> ; <numb> <drug> was; <drug> was reported; was reported to ...

From our initial dataset, we get 1,368 unigram features, 3,959 bigram features, and 5,202 3-gram features. Finally we combine the statistical features and n-gram features to generate a feature vector for every triplet in the dataset. In the later section, we denote (st.)+{1,n}gram as the combination of statistics features and cumulative ‘n’-gram features. For instance, (st.)+{1,3}gram means the feature vector combines statistics features, unigram, bigram, and 3-gram features.

Classification Runs

Algorithms:

Different classification algorithms like Naïve Bayes7, Decision Tree8, and SVM9 perform differently based on the problem addressed. In order to find the best algorithm for our problem, we test three algorithms using 10-fold cross validation with only (st.)+{1,3}gram features and our initial data set. K-fold cross-validation has advantage to reduce variability, and 10-fold is commonly used. And we use the probability of majority class as our baseline (ZeroR in weka). C4.510 (J48 in weka) decision tree was used as decision tree algorithm, and SMO11 was used as the SVM algorithm. The results of the comparison are in Table 5

Table 5:

Comparison of Classification Algorithm Using (st.)+{1,3}gram features

| Algorithm | ZeroR (Baseline) | Naïve Bayes | Decision Tree | SVM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Accuracy (std.) | 62.54 (1.12) | 71.49 (7.96) | 77.10 (6.97) | 81.53 (6.11) |

| Weighted Average F-Measure | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

Accuracy gives the number of instances that are classified correctly. Std. is the standard deviation across the 10 fold-validation. Weighted Average F-Measure is the combination of F-Measure of class True and False, weighted by the number of instances in the two classes. These results show that SVM has the best performance and is significantly better than the baseline. It has more than 80% accuracy. Therefore, we decided to use SVM as our classification algorithm in our later experiments.

N-gram Feature Selection:

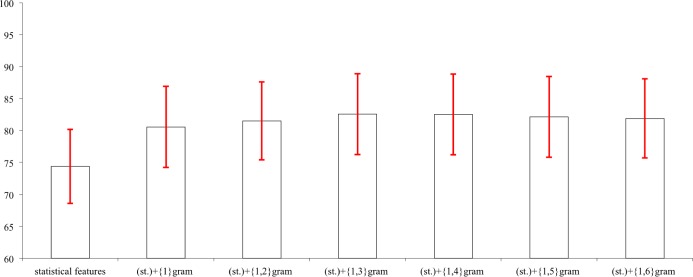

The next question we address is what kinds of features are important for our classifiers. We generated seven different feature vectors for triplets in the dataset, including statistical features (without gram feature), (st.)+{1}gram, (st.)+{1,2}gram, ..., (st.)+{1,6}gram features. Then we use SVM and these seven different feature vectors on our initial data set to run 10-fold cross validation. These results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 4.

Table 6:

Comparison of Different Feature Vectors using SVM

| Features | Accuracy(std.) | Avg. F-Measure | Features | Accuracy(std.) | Avg. F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| statistical features | 74.38(5.81) | 0.71 | (st.)+{1,4}gram | 82.52(6.31) | 0.83 |

| (st.)+{1}gram | 80.55(6.35) | 0.81 | (st.)+{1,5}gram | 82.14(6.32) | 0.82 |

| (st.)+{1,2}gram | 81.53(6.11) | 0.82 | (st.)+{1,6}gram | 81.89(6.19) | 0.82 |

| (st.)+ {1,3} gram | 82.55(6.32) | 0.83 | |||

Figure 4:

Comparison of Different Feature Vectors using SVM

These results show that just using the statistical features is already significant higher than the baseline (ZeroR). So we have good feature selection using statistical features. The n-gram features do even better to improve performance. All of the feature vectors using n-gram achieve more than 80% accuracy. But increasing the n-gram does not mean that the performance always improves. The highest performance is achieved by using (st.)+{1,3}gram, and (st.)+{1,4}gram yields similar performance. Considering the running time of the classifier, (st.)+{1,3}gram is our best choice.

New Test Set Results

Next we test our methods on a new test set as a second validity check. For this we build our classifier with SVM and (st.)+{1,3}gram features using all of our Initial Dataset and test on the New Test Set. The New Test Set contains 20 LtEs randomly sampled from Corpus II and not in the Initial Dataset. Again we use MetaMap to parse the LtE text. We consider the word tagged ‘dsyn’, ‘fndh’, ‘sosy’ and ‘patf’ as the candidate ADEs, with the drug in Substance field of LtE, and generate drug-candidate ADE pairs, then we generate triplets for the test set. These triplet instances were also manually analyzed for labels (True or False). Features of this dataset are described in column 2 of Table 3. Using our classifier we achieved the accuracy 81.82%. Detailed results are in Table 7, and the confusion matrix is shown in Table 8.

Table 7:

Performance of Test Set Using SVM

| Class | TP Rate | FP Rate | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | ROC Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| True | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.795 |

| False | 0.92 | 0.33 | 0.8 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.795 |

| Weighted Average | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.795 |

Table 8:

Confusion Matrix of Test Set Using SVM

| Predicted Class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | False | Total | ||

| Actual Class | True | 24 | 12 | 36 |

| False | 4 | 48 | 52 | |

| Total | 28 | 60 | 88 | |

The classifier has high precision in both classes, and the recall of class False is above 90%. However, recall for class True is not as high as for class False. A reason could be that the non-major ADEs in the LtE create a confounding factor. For example, a LtE claims drug D has ADE A1. It is possible that in addition to discussing A1 and its detailed information, the author will mention another ADE A2 of drug D. A2 might appear once in the LtE, and this is not uncommon. This low frequency appearance is likely not strong enough to be captured appropriately by the statistical features we use. Therefore, it would be classified into Class False. The confusion matrix indicates that the majority of our errors are actually false negative errors. So we are missing signals of drug - ADE links that we should be capturing. This is something we will look further into in future research.

Next we see what kind of features are important. Table 9 shows the top 20 most important features using SVM and our Initial Dataset. Only two statistical features are in the top 20, so n-gram are very important features to detect ADEs. A few of the features are not sensible (a risk with automated methods like SVM) such as ‘times, ‘three times’. However, this may be explained by the fact that the sentence like show the incidence of rash with captopril to be some four times greater than that with enalapril appears often. Another questionable feature is furberg, it refers to Curt D. Furberg, a professor in Wake Forest University whose name repeats in some letters. These oddities point to future research.

Table 9:

Top 20 Most Important Features

| Rank | Features | Rank | Features | Rank | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1 | <fndg> and <dsyn> | 8 | <candidate ade> or <fndg> | 15 | day for |

| 2 | <dsyn> with | 9 | <sosy> and <candidate ade> | 16 | or <dsyn> |

| 3 | receiving <orch;phsu> | 10 | primary | 17 | use of |

| 4 | <orch;phsu> <numb> | 11 | <dsyn> | 18 | or |

| 5 | Both drug cand. ADE are in title | 12 | furberg | 19 | had an |

| 6 | <candidate ade> or | 13 | # times cand. ADE in first part LtE | 20 | three times |

| 7 | <candidate ade> occurred | 14 | times | ||

RELATED RESEARCH

ADE detection methods with free text can be classified into three categories: Rule-based, Statistic-based, Machine Learning-based. Rule-based methods use patterns or association rules to match the drug name and ADE name in text. Usually the precision is not high. Kuo et al.12 demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of using Apriori association algorithm for ADE detection goal. The most widely used statistics-based algorithms are the proportional reporting ratio (PRR)13, reporting odds ratio (ROR)14, information component (IC)15, and the empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM)16. This is consistent with Forster et al. ’s review17. PRR and ROR are frequentist (non-Bayesian), whereas the IC and EBGM are Bayesian.

Few studies compare machine learning results with statistical methods. Wang et al.18 used neural networks and statistical graphical models to find drug relationships from the biomedical literature. But these methods were all designed to extract information at the level of individual sentences. Also their work aims to determine the likelihood of a specific drug-ADE relationship based on the classification of multiple documents associated with the pair.

The work most similar to ours is by Aramaki et al.5 using NLP to automatically extract ADEs from clinical records (Electronic Health Records EHR). They use Named Entity Recognition (NER) methods, conditional random fields(CRF), to identify drug and symptom expression. Then they use both pattern-based and machine learning (SVM) based methods to identify the drug - ADE relation. In contrast, we have a very different data source (LtEs), and our feature selection strategies are also different.

Botsis et al4 selected 6034 VAERS reports for H1N1 vaccine that were classified by medical officers as potentially positive or negative for anaphylaxis. Their goal was only to classify the document, not find ADEs. They demonstrate a multi-level text mining approach for automated text classification that could potentially reduce human workload. Similar work but from a different field is by Conway et al.19 where they explored n-grams and semantic features for classification of disease outbreak reports. They also use Naïve Bayes, C4.5 decision tree and SVM. However, our goal of ADE detection is different. In terms of data analyzed there is research in detecting adverse events, from patient clinical records5, from DrugBank database1, from PubMed articles2, from narrative discharge summaries of clinical information system3, from Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System VAERS4. These were also introduced earlier.

CONCLUSION

We demonstrate that LtEs contain early signals of adverse drug effects. We successfully designed automatic ADE detection methods with off-the-shelf machine learning and NLP tools. We chose a sufficient number and variety of useful feature types for our classifier to achieve high performance. And importantly, our method adapts nicely to a new test set. However, we only find the candidate ADEs in four semantic types of MetaMap tags, we will look for candidate ADEs in more semantic types (groups) as described by Bodenreider and McCray20. It will ensure that events are adequately detected as suggested by anonymous reviewer. In addition, our experiments are limited by the size of the datasets. The selection of LtE in Initial Dataset is not by random but heuristic match in the previous research, those LtEs in Initial Dataset may have higher rates of ADEs, compared to the average one in the overall corpus of LtEs. The New Test Set works find but the performance may be different if the number of labeled LtEs is much more than 20. However, this is a new direction of research, as LtEs in journals have never before been exploited for drug ADE detection. The sizable time lag (in months and years) between ADE indications in LtEs and notations in Micromedex underlines the importance of LtEs. In future research, we will gather more annotated data, and we will explore additional features. We also plan to explore new feature types. For example, we have not used any data about ADEs linked to other members of a given drug’s family. Finally, we would like to explore more systems like SemRep, and more advanced algorithms. Our results are encouraging and give us the confidence that this direction of research is worth expanding upon. We conclude that it is worth going through the trouble of collecting the full text equivalents of these letters (so sparsely indexed in MEDLINE) and analyzing them for ADEs. Thus we see ample scope for future research on ADEs and LtEs.

Footnotes

Micromedex Healthcare Series [Internet database] Greenwood Village, Colo: Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc. Updated periodically.

References

- 1.Vilar S, Harpaz R, Chase HS, Costanzi S, Rabadan R, Friedman C. Facilitating adverse drug event detection in pharmacovigilance databases using molecular structure similarity: application to rhabdomyolysis. JAMIA. 2011 Dec.18(Suppl 1):i73–i80. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty KD, Dalal SR. Using information mining of the medical literature to improve drug safety. JAMIA. 2011 Aug.18(5):668–674. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Hripcsak G, Markatou M, Friedman C. Active computerized pharmacovigilance using natural language processing, statistics, and electronic health records: a feasibility study. AMIA. 2011 Sep;16(3):328–337. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botsis T, Nguyen MD, Woo EJ, Markatou M, Ball R. Text mining for the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System: medical text classification using informative feature selection. JAMIA. 2011 Aug;18(5):631–638. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aramaki E, Miura Y, Tonoike M, Ohkuma T, Masuichi H, Waki K, et al. Extraction of adverse drug effects from clinical records. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160(Pt 1):739–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Simmering J, Srinivasan P, Polgreen L, Polgreen P. Early detection of adverse drug events using the full text of letters to the editor. EHTJ. 4(11103):2011. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.v4i0.11103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.John George H, Langley Pat. Estimating continuous distributions in Bayesian classifiers. 7th Conference on UAI; 1995. pp. 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986 Mar;1(1):81–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1022643204877. ISSN 0885-6125. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022643204877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vapnik VN. The nature of statistical learning theory. HeidelbergA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinlan Ross. C45: programs for machine learning. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; San Mateo, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt John C. Fast training of support vector machines using sequential minimal optimization. In: Schoelkopf B, Burges C, Smola A, editors. Advances in Kernel Methods - Support Vector Learning. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo MH, Kushniruk AW, Borycki EM, Greig D. Application of the Apriori algorithm for adverse drug reaction detection. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;148:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans SJW, Waller PC, Davis S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2002;10(6):483–486. doi: 10.1002/pds.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman Kenneth J, Lanes Stephan, Sacks Susan T. The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2004 Aug.13(8):519–523. doi: 10.1002/pds.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bate A, Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Olsson S, Orre R, Lansner A, et al. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998 Mar;54:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s002280050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szarfman Ana, et al. Use of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDAs spontaneous. Drug Saf. 2002 Sep;25:381–392. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster AJ, Jennings A, Chow C, Leeder C, van Walraven C. A systematic review to evaluate the accuracy of electronic adverse drug event detection. JAMIA. 2011 Dec;19(1):31–38. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Wei, et al. A drug-adverse event extraction algorithm to support pharmacovigilance knowledge mining from PubMed citations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc; 2011. Oct, 2011. pp. 1464–1470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway Mike, Doan Son, Kawazoe Ai, Collier Nigel. Classifying disease outbreak reports using n-grams and semantic features. Int J Med Inform. 2009 Dec;78(12):e47–e58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodenreider Olivier, McCray Alexa T. Exploring semantic groups through visual approaches. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2003 Dec;36(6):414–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]