Abstract

Successful immunization against challenging infectious diseases requires novel approaches to vaccine design. To control diseases of high human health impact such as AIDS and influenza by vaccination requires an understanding of the mechanisms of viral entry and identification of highly conserved vulnerable regions of the virus to which immune responses are not normally directed. Structural biology has provided important information about the three-dimensional organization and chemical structure of the HIV-1 and influenza glycoproteins. By harnessing structural biology, monoclonal antibody specificity, genomics, and informatics, we have been able to define neutralizing antibodies of exceptional breadth and potency against circulating strains of HIV-1, and we have begun to develop immunogens to elicit such antibodies. Similarly, for influenza, understanding of this target has led to structural and genetic approaches to the development of new immunogens that provide a proof of concept for universal influenza vaccination.

Our work is focused on the rational design of vaccines for AIDS and influenza viruses. To develop more effective preventive and therapeutic interventions for these challenging infectious diseases, we are attempting to understand the reason it has been so difficult to elicit effective protective immunity and how scientific advances can help solve these problems. For human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV), two problems have made it difficult to develop an effective vaccine. First, unlike almost every infectious disease where a single virus or a small subset of viruses is the target of the human immune system, there are many millions of different HIV-1 strains that have generated considerable diversity. Thus, there is a need to develop a vaccine not against a single virus but against an infinite number of viruses. The role of antibodies in mediating protection against HIV-1 has been questioned over the years because most of the antibodies generated to these viruses are strain-specific and not common to the highly conserved regions of the virus. A further challenge comes from the constant genetic mutation of the virus. Even within a single individual, the virus can give rise to millions of variants. So the virus presents a moving genetic target.

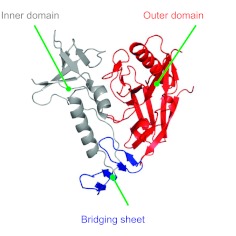

A second challenge comes from the behavior of the viral envelope, the part of the virus that attaches to the CD4 host cell to initiate infection. This protein has developed a number of biochemical features that allow it to evade neutralization. To solve this problem, we have worked with structural biologists, particularly Peter Kwong at the Vaccine Research Center, to help elucidate the structure of the HIV Envelope (Env) protein (reviewed in (1)). This knowledge allows an understanding of the molecular “geography” of this virus (Fig. 1). The Env protein is composed of three major regions: an outer domain, an inner domain, and a sheet that bridges between them. Between the outer and inner domains is the highly conserved region that is recognized initially by the CD4 molecule to which the virus binds (2). After that initial contact, it extends its area of contact, promoting multiple interactions between the viral protein and the host receptor, facilitating viral entry into the cell. This structural information facilitates identification of the vulnerabilities for a vaccine and suggests potential modifications of these structures that might enable the generation of successful vaccine candidates. While this structure is the Env monomer, on the surface of the virus, the viral spike is composed of a trimer, meaning there are three viral envelope proteins in each spike. Complicating vaccine development further, the viral envelope is heavily glycosylated with host-derived carbohydrates that the immune system recognizes as “self,” masking the virus. Thus, the immune system has a narrow window to recognize highly conserved structures on the viral surface.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the HIV-1 Envelope viral glycoprotein. A ribbon diagram representation of the stabilized core region of the gp120 subunit from the HIV-1 viral spike depicts its molecular geography, including an outer domain (red), inner domain (gray) and bridging sheet (blue). Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. (3)

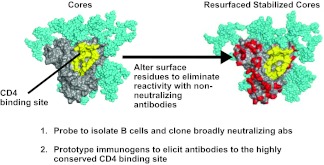

How can this knowledge be used to develop new vaccines and improved treatments? One approach is to modify this protein to make non-physiological and non-infectious forms of it that expose highly conserved and functionally required regions that are targets of broadly neutralizing antibodies. One such structure on the HIV viral envelope is the CD4 binding site. With our knowledge of structure, we are able to artificially alter the surface of the protein (Fig. 2; shown in red) so that we can present only the region of interest to the immune system (2, 3). These proteins can then be used as probes to isolate such antibodies from B cells of people who are infected by HIV that recognize this region specifically. We can also use them as prototype vaccines that would increase recognition of this region. With this approach, with my collaborators John Mascola, Peter Kwong, and their laboratories, as well as other partners, we have been able to isolate the relevant B cells, rescue their immunoglobulin transcripts, and identify a number of exceptionally broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV (4, 5). They recognize the CD4 binding site and neutralize with considerable potency. Prior to last year, the best broadly neutralizing antibody to this site could neutralize about 40% of viruses, primarily those of one specific type, clade B; now we are able to neutralize over 90% of circulating strains. These new antibodies have been honed to recognize this specific site (6). The binding of this antibody can prevent the virus from attaching to its target cell. These extraordinary new antibodies have been isolated with the benefit of recent advances in scientific technology and provide encouragement that a vaccine that elicits them can prevent infection against many diverse circulating strains. Such antibodies provide a proof-of-concept that broadly neutralizing antibodies can be made in humans and protect against infection.

Fig. 2.

Resurfaced stabilized core HIV-1 Env proteins define antibodies to the CD4 binding site and serve as prototype vaccines. Modification of surface exposed residues of the HIV-1 Env (left) and substitution with divergent amino acids (red) allow development of a defined protein (right) that can be used to analyze sera and isolate monoclonal antibodies, as well as a prototype that can serve as an immunogen to elicit similar antibody responses. Reprinted from Figure 2 of (1) with permission from The Royal Society, 6-9 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AG, United Kingdom.

At the Vaccine Research Center, we have furthered our understanding of these immune responses by performing deep sequencing to clone and express hundreds of such antibodies from patients from around the world (5). Others have since also isolated such antibodies using similar probes that we have developed in the past (7, 8). These antibodies are readily generated in humans from multiple subjects around the world, despite the fact that their immune systems have been profoundly weakened by HIV-1 infection. We now have insight into this problem that was not available even 2 years ago. VRC01 has thus provided a window into understanding more about these broadly neutralizing antibodies. Using this knowledge, especially the additional antibodies defined by deep sequencing, we have been able to open new vistas for antibody-mediated protection against HIV. Importantly, this genetic information is allowing us to trace the pathways of development of these antibodies, and now we can use them as guides for vaccine design—to tell us how to evolve the antibody response to develop a highly effective vaccine that will elicit them.

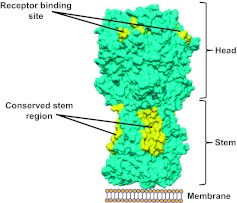

The problems with influenza viruses resemble those with HIV in that there is significant seasonal variation, although the genetic diversity of influenza viruses is considerably less than with HIV-1. Each year, new seasonal influenza vaccines are manufactured for clinical use, at a cost of $3 billion to $4 billion dollars annually. Even with these vaccines, more than 200,000 people succumb to influenza virus infections worldwide each year. Thus, vaccines with greater potency and breadth could have both a public health impact and an economic benefit. As with HIV-1, an understanding of the structure of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) protein is the basis for our current efforts. The trimeric viral HA attaches to its target cell (analogous to HIV Env), and there are conserved regions, one in the stem region, which undergoes conformational changes, and another in the receptor binding site, that are required for viral entry (Fig. 3, yellow). These highly conserved, largely invariant regions represent targets of broadly neutralizing antibodies (9–11). In essence, we can approach influenza vaccine design similarly to HIV by focusing on these regions.

Fig. 3.

Molecular representation of the influenza virus spike and two highly conserved regions of vulnerability. The spike is composed of a trimeric HA with an upper (head) and lower (stem) region that together are required for entry into respiratory tract cells. The location of the highly conserved sites in the receptor binding region and stem are highlighted (yellow).

New technology has allowed the use of structural design to create vaccine candidates. New tools include not only protein-based design but also the use of nanotechnology to create physiologic forms of viral spikes on nanoparticles that can elicit broadly neutralizing antibody responses. Such prototype vaccines have several potential advantages. First, they can form spikes very similar to those on the surface of influenza but without any other viral components that cause disease. It is thus possible to make forms of HA in a way that nature never intended but that improve antigen presentation to the immune system. This effect can also be achieved with other technology, for example, using gene-base prime boost vaccination to elicit remarkable breadth of neutralization. For instance, the 1999 inactivated vaccine would normally elicit neutralization to the matched viral strain from the same year or those closely related to it. When we used gene-based prime boost immunization, we not only improved the neutralization of the homologous virus, we could neutralize a virus that did not yet exist in 1999, a 2007 strain (12). We could even go back to 1934 viruses and begin to elicit antibodies to a virus that had been in circulation 80 years ago (12) but not since. These new technologies are beginning to enable improvements that may translate into better efficacy of future vaccines, with the ultimate goal of developing a universal influenza vaccine.

Through an understanding of viral entry, we aim to improve vaccine development for highly pathogenic infectious agents, specifically by targeting the highly conserved invariant structures on viruses. Using defined proteins to elicit antibodies to them has allowed us to develop new targets of antibody neutralization, structural serotypes that can be presented to the immune system with novel delivery technology. All licensed human vaccines have succeeded by mimicking natural immunity. With challenging infectious disease targets, such as HIV-1, influenza, TB, and malaria, natural human immunity has failed to contain infectious outbreaks. Our knowledge of structure is enabling a response that normally does not occur in nature, “unnatural immunity” (13). While not completely unnatural, this approach opens a window on penetrating the defenses that viruses have evolved and opportunities to contain them more effectively in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work would not be possible without the collaboration of numerous laboratories, especially those of Peter Kwong, John Mascola, Mario Roederer and other investigators at the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH. My thanks go to Jeffrey Boyington for helpful discussions and assistance in generating Figure 3, to Ati Tislerics and Tina Suhana for manuscript preparation, and to Brenda Hartman for graphics support. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Burns, Gainesville: Gary, can you comment on the ability of the new general flu vaccine to extend beyond the current human hemagglutinins?

Nabel, Bethesda: You mean can we have other targets for vaccination.

Burns, Gainesville: Such as H5 or others?

Nabel, Bethesda: Well as you know better than I, the current licensed vaccines show efficacy only towards the strains for which they are developed. You occasionally see a little bit of cross-reactivity with H5 but it's very poor and I think from a public health perspective, it would contribute almost nothing.

Burns, Gainesville: I thought I saw a couple papers published where, in fact, I think it was in Science, where they actually found success looking at the conserved region and the ability to cover all group 1 and 2 flu viruses.

Nabel, Bethesda: Yes, so there have been a number of the antibodies like the ones that I have shown you and they have come from different groups. The lessons have been, at least for the stem antibodies, the stem antibodies come in two flavors; one that covers all the major groups and the one to which you are referring to comes from a recent paper from Antonio Lanzavecchia, which was quite interesting because it covered all of the viruses from both groups 1 and 2. The problem that we have for vaccine development is that those antibodies are exceptional. The ones that are group-specific are more common, and they are encoded by precursors that we know in our human genome. The one by Lanzavecchia is very unusual, and it's going to be a challenge to induce it. Having said that, either way that we can get there, whether we induce one antibody that covers all or we induce three antibodies that cover all subtypes, would be fine.

Burns, Gainesville: Right. Thank you.

Quesenberry, Providence: There have been some reports that exosomes and microvesicles may mediate HIV entry in the cells. I just would be interested in your comments. Is that a problem and how would you deal with that?

Nabel, Bethesda: It is a potential problem, especially for treatment and so what we are learning is that many of our drug therapies directed to HIV do quite well at targeting a virus once it goes through its complete viral life cycle but there can be short circuits in terms of cell-to-cell transmission where antiretroviral drugs can actually be very challenging. There is actually a recent paper from David Baltimore's lab in Nature on this if you want to read more about it. From the vaccine perspective, it's also a concern because we worry about whether virus could be transferred under the radar screen. Our proposed solution and our hope for dealing with the problem is to use antibodies induced by vaccines that can also stimulate T-cell responses, which would be able to actually locate the virus-producing cells and kill them. So we think there is a way to address that the problem, though we have to demonstrate it in people.

Schwartz, Philadelphia: Are these highly conserved invariant components or areas? Do they bind other things that the cell really needs in other words and if so, is there a way to figure that out before we start using this broadly?

Nabel, Bethesda: Well for HIV, the highly conserved region that we are looking at binds to CD4. It does pose a practical question for vaccine development because if we created an immunogen that was a perfect match to CD4, when we injected that vaccine, it would bind to CD4. These resurfaced cores were designed specifically so that the highly conserved initial region of contact was retained but the other elements required for stable CD4 binding, the ones that crept down toward the bridging sheet (in the yellow picture that I showed you) are gone. So they actually don't bind with high affinity to CD4. They present the conserved site, but they don't bind to CD4, and that's the way we get around it. We can apply an analogous strategy to flu as well. So it is a very important point and something we have to work on.

Glass, Bethesda: Gary, lovely presentation. One of the issues that seems critical for the flu vaccine is that in the elderly, there seems to be some kind of immune change so that even the current vaccines that are targeted specifically to the existing or the circulating strains, don't protect the elderly well and I guess that's quite controversial. Is there anything you can do with the new formulation of flu vaccines that might juice up the immune system at the same time, especially in the elderly who are most likely to be at risk?

Nabel, Bethesda: Excellent point, Roger. I think obviously the two black holes for flu vaccination, aside from the strain variability, are the very young and the very elderly. There has been progress recently from Novartis using their MF59 adjuvant in the very young, and they are now getting quite good coverage with the seasonal flu vaccine in the young using MF59 where it hasn't worked before. We are starting to look at that in the elderly as well, and I didn't have time to talk about it but one of the other approaches we are taking to stimulating these antibodies with highly-conserved residues is to use different prime boost immunization strategies. We've shown, in both animals and in humans, that if you use a DNA prime and follow it with the traditional vaccine boost, you recruit many, many more T-cells. So we have trials that are ongoing to specifically address the question that you asked—to see if that extra stimulus to the T-cell side can give enough help in the elderly to stimulate more effective responses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nabel GJ, Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Progress in the rational design of an AIDS vaccine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:2759–65. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, et al. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–59. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, et al. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329:856–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, et al. Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science. 2011;333:1593–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou T, Georgiev I, Wu X, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329:811–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey B, Svehla K, Xu L, et al. Structure-based stabilization of HIV-1 gp120 enhances humoral immune responses to the induced co-receptor binding site. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000445. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, et al. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science. 2011;333:1633–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, et al. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:265–73. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, et al. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science. 2009;324:246–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittle JR, Zhang R, Khurana S, et al. Broadly neutralizing human antibody that recognizes the receptor-binding pocket of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14216–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111497108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei CJ, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, et al. Induction of broadly neutralizing H1N1 influenza antibodies by vaccination. Science. 2010;329:1060–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1192517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nabel GJ, Fauci AS. Induction of unnatural immunity: prospects for a broadly protective universal influenza vaccine. Nat Med. 2010;16:1389–91. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]