Abstract

Oxidative stress is involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the brain, protect neurons from reactive oxygen species (ROS) and provide them with trophic support, such as glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). Thus, any damage to astrocytes will affect neuronal survival. In the present study, an infusion prepared from the desert plant Pulicaria incisa (Pi) was tested for its protective and antioxidant effects on astrocytes subjected to oxidative stress. The Pi infusion attenuated the intracellular accumulation of ROS following treatment with hydrogen peroxide and zinc and prevented the H2O2-induced death of astrocytes. The Pi infusion also exhibited an antioxidant effect in vitro and induced GDNF transcription in astrocytes. It is proposed that this Pi infusion be further evaluated for use as a functional beverage for the prevention and/or treatment of brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases in which oxidative stress plays a role.

1. Introduction

Increased life spans in the Western world have led to an elevated frequency of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Neurodegenerative diseases are the result of gradual and progressive loss of neural cell function.

Oxidative damage plays a pivotal role in the initiation and progress of many human diseases and is considered to be a salient and early pathogenetic event in many neurodegenerative disorders that are characterized by selective neuronal death [1–5]. Compared with other tissues, the brain is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to its high rate of oxygen utilization and the great deal of oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids it contains [6, 7]. In addition, certain regions of the brain are rich in iron, a metal that is catalytically involved in the production of damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8]. Although ROS are critical intracellular signaling messengers [9], an excess of free radicals may lead to peroxidative impairment of membrane lipids and, consequently, to the disruption of neuronal functions and apoptosis. The ROS known to be responsible for neurotoxicity are hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2 −), and hydroxyl radicals (OH−).

Brain cells have the capacity to produce large quantities of peroxides, particularly H2O2 [10]. Excess, H2O2 accumulates in response to brain injuries and during the course of neurodegenerative diseases and can cross cell membranes to elicit biological effects from inside the cells [11]. Although H2O2 is generally not very reactive, it is thought to be the major precursor of highly reactive free radicals that may cause damage in the cell, through iron ion- or copper ion-mediated oxidation of lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. This capability can partially account for H2O2-mediated neuronal [12] and glial [13] death. H2O2 also induces differential protein activation, which accounts for its varied biological effects. In the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), the transition metal zinc is found only in the synaptic vesicles of glutamatergic neurons and plays a special role in modulating synaptic transmission. Chelatable zinc is released into the synaptic cleft with the neurotransmitter during neuronal execution [14]. Under normal circumstances, the robust release of zinc is transient and the zinc is efficiently cleared from the synaptic cleft to ensure the performance of successive stimuli. However, under pathological conditions, elevated levels of extracellular zinc have been recognized as an important factor in neuropathology [15–17]. In neurotransmission, the amount of zinc in the synaptic cleft is in the range of 10 to 30 μM, but, under pathological conditions that involve sustained neuronal depolarization (e.g., ischemia, stroke or traumatic brain injury), the concentration of extracellular zinc can increase to 100 to 400 μM, which can contribute to the resulting neuropathology [18, 19]. In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that at concentrations that can be reached in the mammalian CNS during excitotoxic episodes, injuries or diseases, zinc induces oxidative stress and ROS production, which contribute to the death of both glial cells [20] and neurons [21, 22]. Zinc has been shown to decrease the glutathione (GSH) content of primary cultures of astrocytes [20, 23], increase their GSSG content [23], and inhibit glutathione reductase activity in these cells [24]. Furthermore, it slows the clearance of exogenous H2O2 by astrocytes and promotes intracellular production of ROS [24]. Thus, ROS generation, glutathione depletion, and mitochondrial dysfunction may be key factors in ZnCl2-induced glial toxicity [20].

Astrocytes are the most abundant type of glial cell in the brain and play multiple roles in the protection of brain cells. Under ischemic conditions, astrocytes can remove excess glutamate and K+ to protect neurons from glutamate-mediated cytotoxicity and depolarization [25, 26]. Astrocytes can also supply energy and promote neurogenesis and synaptogenesis in response to ischemia-induced brain damage [27, 28]. Astrocytes release multiple neurotrophic factors, such as GDNF, to protect themselves and neighboring cells from in vitro ischemia and there is evidence that dysfunctional astrocytes can enhance neuronal degeneration by decreasing the secretion of trophic factors [29]. GDNF can promote the survival of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons, induce neurite outgrowth and sprouting [30–32], upregulate tyrosine hydroxylase expression, and enhance synaptic efficacy [33]. Moreover, GDNF has been shown to protect cultured astrocytes from apoptosis after ischemia by inhibiting the activation of caspase-3 [34].

The study of astrocytes is particularly important in light of the coexistence of apoptotic death of neurons and astrocytes in brains affected by ischemia and neurodegenerative diseases. Despite their high levels of antioxidative activity, astrocytes exhibit a high degree of vulnerability and are not resistant to the effects of ROS. They respond to substantial or sustained oxidative stress with increased intracellular Ca2+, loss of mitochondrial potential, and decreased oxidative phosphorylation [35]. Since astrocytes determine the brain's vulnerability to oxidative injury and form a tight functional unit with neurons, impaired astrocytic energy metabolism and antioxidant capacity and the death of astrocytes may critically impair neuronal survival [36, 37]. Thus, protection of astrocytes from oxidative stress appears essential for the maintenance of brain function.

Based on the pathophysiological roles of astrocytes in ischemic brains, it appears that astrocyte damage causes impairment of brain function during cerebral ischemia. In recent years, there has been an increased interest in plants as a source of bioactive substances that might be developed as potential nutraceuticals and various activities of such substances have been demonstrated in in vitro and in vivo experimental systems [38]. Several studies have shown that some herbal medications and antioxidants show promise toward preventing Alzheimer's disease [39–41].

Pulicaria incisa (Pi) is a desert plant that belongs to the Asteraceae family and has been used for many years in traditional medicine for the treatment of heart disease and as a hypoglycemic agent [42–44]. Pi has been found to contain high amount of unsaturated fatty acids [45], to decrease total lipid, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels, and has been proposed as a potential hypocholesterolemic agent [46]. A Pi infusion is consumed in place of tea by many Egyptian Bedouins [42, 43, 47]. To the best of our knowledge, its effects in the context of neurodegenerative diseases have not yet been studied.

In light of the fact that oxidative stress has become accepted as a target of therapeutic interventions for the treatment of brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases and the critical role of astrocytes in neuronal survival, the present study examined the effects of an infusion prepared from Pi on the susceptibility of astrocytes to oxidative stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), Leibovitz-15 medium, glutamine, antibiotics (10,000 IU/mL penicillin and 10,000 μg/mL streptomycin), soyabean trypsin inhibitor, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Biological Industries (Beit Haemek, Israel); dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) was obtained from Applichem (Darmstadt, Germany) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (OH, USA). ZnCl2, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). 2,2′-Azobis(amidinopropane) (ABAP) was obtained from Wako chemicals (Richmond, VA,USA).

2.2. Experimental Animals

Newborn Wistar rats (0–2 days old) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories. The experiments were performed in compliance with the appropriate laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee of the Volcani Center, Agricultural Research Organization (number IL-135/07).

2.3. Preparation of Pi Infusion

The plants were collected in Nekarot Wadi in the Arava Valley on April, 2005, and the plant's voucher specimen (M86) has been kept and authenticated as part of the Arava Rift Valley Plant Collection; VPC (Dead Sea & Arava Science Center, Central Arava Branch, Israel, http://www.deadseaarava-rd.co.il/_Uploads/ dbsAttachedFiles/Arava_Rift_Valley_Plant_Collection.xls) under the accession code AVPC0193. Freshly collected plants were dried in 40°C for three days. Preparation of Pi infusion was initiated by soaking a 15 mL tube containing dried Pi (1 gr/10 mL) in a beaker containing 200 mL boiling DDW. The beaker was allowed to cool at RT for 30 min. The tube was centrifuged (4000 RPM, 10 min, RT), the supernatant was collected, filtered, and aliquots were stored at −20°C until use. In order to determine the extract concentration, a sample of the filtered supernatant was lyophilized to obtain extract powder. The averaged concentration of the various preparations that were tested was 10 mg/mL.

2.4. Preparation of Primary Astrocytes Cultures

Cultures of primary rat astrocytes were prepared from cerebral cortices of 1-to-2-day-old neonatal Wistar rats. Briefly, meninges and blood vessels were carefully removed from cerebral cortices kept in Leibovitz-15 medium; brain tissues were dissociated by trypsinization with 0.5% trypsin (10 min, 37°C, 5% CO2); cells were washed first with DMEM containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 μg/mL) and 10% FBS and then with DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were seeded in tissue culture flasks precoated with poly-D-lysine (PDL, 20 μg/mL in 0.1 M borate buffer pH 8.4) and incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. The medium was changed on the second day and every second day thereafter. At the time of primary cell confluence (day 10), microglial and progenitor cells were discarded by shaking (180 RPM, 37°C) for 24 h. Astrocytes were then replated on 24-well PDL-coated plastic plates, (a) for toxicity assays, at a concentration of 1 × 105/well, in DMEM (without phenol red) containing 2% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL pennicilin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. (b) For the cellular antioxidant activity assay at a concentration of 3 × 105/well, in DMEM containing 10% FBS 8 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL pennicilin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

2.5. Treatment of Astrocytes

Twenty four hours after plating, the original medium in which the cells were grown was aspirated off, and fresh medium was added to the cells. Dilutions of Pi infusion, ABAP, DCF-DA, zinc, and of H2O2 in the growth medium were made freshly from stock solutions prior to each experiment and were used immediately.

2.6. Evaluation of Intracellular ROS Production

Intracellular ROS production was detected using the nonfluorescent cell permeating compound, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA). DCF-DA is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases and then oxidized by ROS to a fluorescent compound 2′-7′-DCF. Astrocytes were plated onto 24-well plates (300,000 cells/well) and treated with DCF-DA (20 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Following incubation with DCF, cultures were rinsed twice with PBS and then resuspended. (1) For measurement of H2O2-induced ROS: in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 8 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. (2) For measurement of ZnCl2 -induced ROS: in a defined buffer containing 116 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 14.7 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM HEPES, pH, 7.4. The fluorescence was measured in a plate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm.

2.7. Cellular Antioxidant Activity of Pi Infusion

Peroxyl radicals are generated by thermolysis of 2,2′-Azobis(amidinopropane) (ABAP) at physiological temperature. ABAP decomposes at approximately 1.36 × 10−6 s−1 at 37°C, producing at most 1 × 1012 radicals/mL/s [48–50]. Astrocytes were plated onto 24 wells plates (300,000 cells/well) and were incubated for 1 hr with Pi infusion. Then astrocytes were preloaded with DCF-DA for 30 min, washed, and ABAP (0.6 mM final concentration) was then added. The fluorescence, which indicates ROS levels, was measured in a plate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm.

2.8. Induction of GDNF in Astrocytes

Astrocytes were replated at 6-well PDL-coated plastic plates at a density of 2 × 106/well, in DMEM/F12 containing 5% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL pennicilin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Twenty-four hr after plating, the original medium of the cells was aspirated off and fresh medium was added to the cells. Cells were then lysed and collected using RLT buffer containing 1% βME for RNA extraction.

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted by the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was removed from the RNA samples by using 50 units of RNase-free DNaseI at 37°C for 1 h. RNA (20 μg) was converted to cDNA using the Thermo Scientific Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA was used for quantitative real-time PCR amplification with TaqMan chemistry (Applied Biosystems) using Rat GDNF predesigned TaqMan Gene Expression Assay from Applied Biosystems (Assay ID Rn00569510). Values were normalized relative to rat glyceraldehyde-3-phospahte dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Assay ID Rn00569510). All results from three technical replicates were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as relative expression ratios calculated (relative quantity, RQ) using the comparative method and based on the data that were created by the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (using version 1.6 software).

2.10. Determination of Cell Viability

Cell viability was determined using a commercial colorimetric assay (Roche Applied Science, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This assay is based on the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity released from the cytosol of damaged cells into the growth medium.

2.11. Determination of the Free Radical Scavenging Activity in the DPPH Assay

Antioxidant activity was measured using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryhydrazyl DPPH radical scavenging assay. Different dilutions of the infusion (0.15 mL) were added to 1 mL of DPPH (3.9 mg/100 mL methanol) in test tubes wrapped in aluminum foil. Absorbance (A) was measured at 517 nm after 15 min incubation in the dark. All measurements were made with distilled water as blank. The scavenging ability (%) of the samples was calculated as (Acontrol − Asample)/Acontrol × 100).

2.12. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison tests using Graph Pad InStat 3 for windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. The Pi Infusion Protected Astrocytes against H2O2-Induced Cell Death

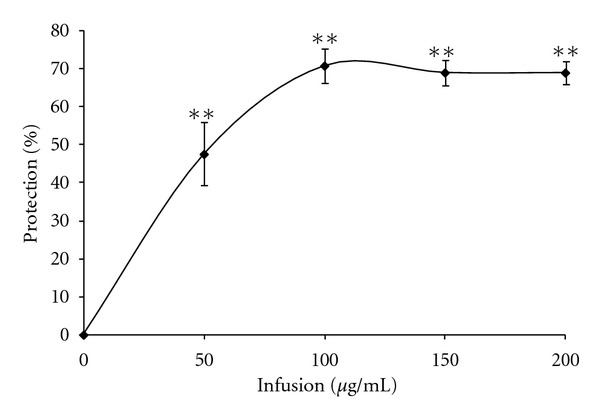

H2O2 exposure is used as a model of ischemia reperfusion. The concentration of H2O2 used in our experiments (175–200 μM) resembles the concentration reported in rat striatum under ischemic conditions [3]. In order to characterize the ability of the Pi infusion to protect against H2O2-induced oxidative stress, we assessed changes in cell viability and intracellular ROS production, using a model in which oxidative stress was induced by the addition of H2O2 to cultures of primary astrocytes. Exposure of normal primary astrocytes to H2O2 resulted in the time and concentration-dependent death of astrocytes at 20 h after exposure (data not shown). To find out whether the Pi infusion has a protective effect and to determine the optimal concentration of the extract needed for such an effect, astrocytes were pre-incubated with different concentrations of Pi infusion. H2O2 was then added and was determined after 20 h. Our results show that the Pi infusion exhibited a protective effect against H2O2-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pi infusion protects astrocytes from H2O2-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner. Astrocytes were treated with different concentrations of a Pi infusion. H2O2 was added 2 h after the addition of the Pi infusion and cell death was determined 20 h later. The results are mean ± SEM of four experiments (n = 16). **P < 0.001.

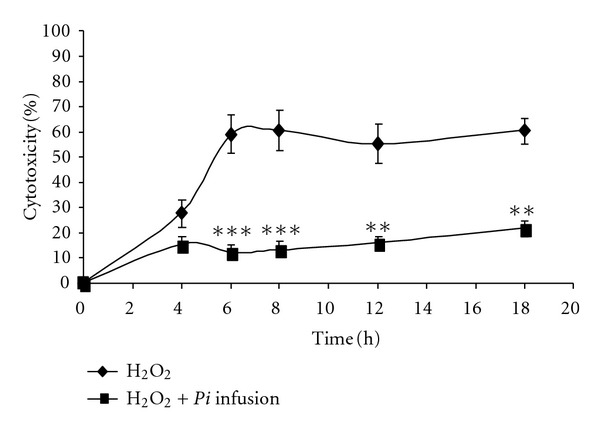

The kinetics of H2O2 cytotoxicity and inhibition in the presence of the Pi infusion are presented in Figure 2. As shown in that figure, H2O2-induced cytotoxicity reached its maximal level 6 h after the application of H2O2. The Pi infusion prevented the increased incidence of cell death for at least 18 h—the latest time point examined.

Figure 2.

Time course of the protective effect of the Pi infusion on astrocytes. Astrocytes were preincubated with the Pi infusion (100 μg/mL) for 2 h. H2O2 was then added and cytotoxicity was measured at the indicated time points. The results are the means ± SEM of four experiments (n = 16). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared to cells treated with H2O2 only.

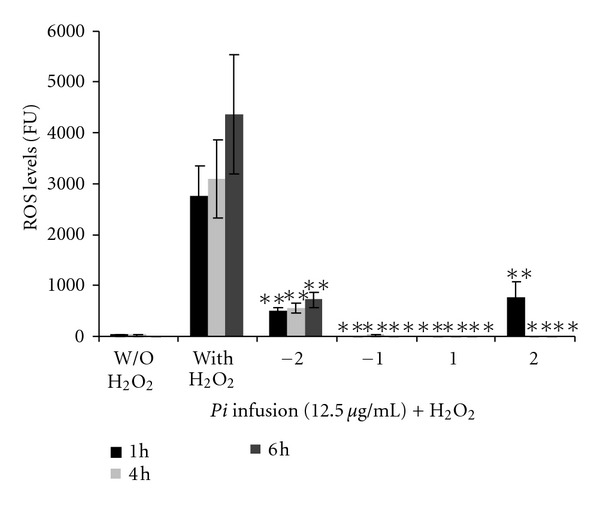

To determine the optimal timing of the application of the Pi infusion to ameliorate the effect of H2O2, the cells were pre-incubated with Pi infusion for 2 h or 1 h, cotreated or posttreated with H2O2. Our results demonstrate that the Pi infusion is more effective when applied to the cells before H2O2 and that the addition of Pi infusion to the cells after the application of H2O2 did not provide significant protection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Preincubation of astrocytes with Pi infusion is a prerequisite for the protective effect against H2O2 cytotoxicity. Pi infusion (12.5 μg/mL) was added to astrocytes before (−2 h, −1 h) or after (1 h, 2 h) the addition of H2O2. Cytotoxicity was measured 20 h later. The results are means ± SEM of one experiment (n = 4) out of three independent experiments. **P < 0.001 *P < 0.01.

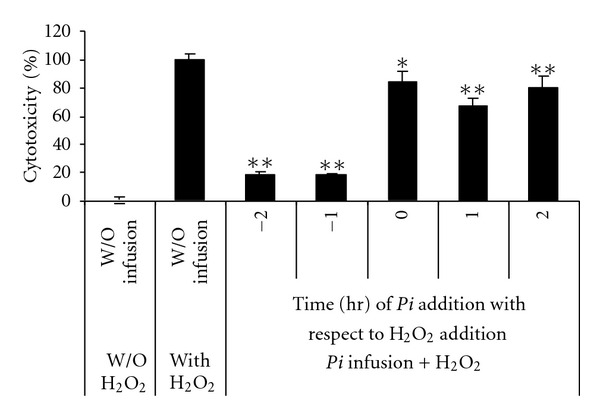

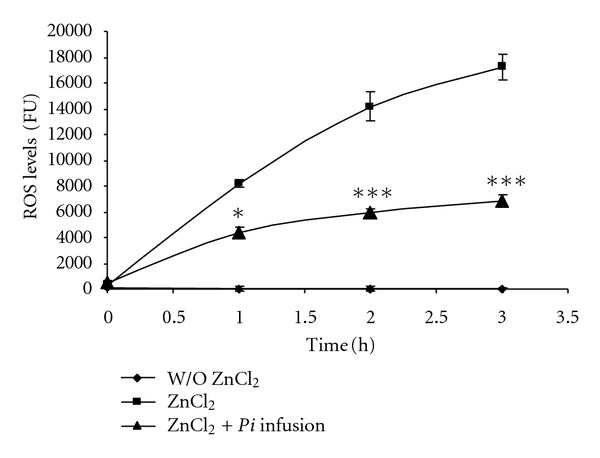

3.2. The Pi Infusion Inhibited the H2O2- and ZnCl2-Induced Generation of ROS

H2O2-induced cell death is accompanied by an increase in ROS levels. In order to determine whether our Pi infusion could inhibit the production of ROS that is induced by H2O2, we assessed the intracellular generation of ROS and tested whether treatment of astrocytes with the Pi infusion affected intracellular ROS levels. For the study of the preventive effects against intracellular ROS formation, the cells were preloaded with the ROS indicator DCF-DA and were treated with various concentrations of Pi infusionbefore the application of H2O2. ROS formation was determined by examining fluorescence every hour for 4 h. As shown in Figure 4(a), H2O2 induced the production of ROS in astrocytes, with the maximum levels of ROS produced after 1 h. Pretreatment of astrocytes with the Pi infusion inhibited the H2O2-induced elevation of the levels of intracellular ROS in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4(b)). We also found that treatment with ZnCl2 increased ROS generation in astrocytes and that, similar to the effect of the Pi infusion H2O2-induced generation of ROS, this infusion greatly attenuated ZnCl2-induced ROS generation (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Pi infusion attenuates H2O2-induced ROS production in astrocytes. Astrocytes were preloaded with the redox-sensitive DCF-DA for 30 min and washed with PBS. Preloaded astrocytes were then pre-incubated with various concentrations of Pi infusion for 2 h. H2O2 (175 μM) was added to the culture and the fluorescence intensity representing ROS production was measured. (a) The fluorescence levels of cells that had been preincubated with 100 μg/mL Pi extract were measured at the indicated time points. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 Compared to cells treated with H2O2 only. (b) The fluorescence levels of cells that had been pre-incubated with various concentrations of Pi extract were measured after 3 h. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of two experiments (n = 8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Zinc induces ROS generation and the Pi infusion attenuates ROS production following treatment of astrocytes with zinc. Astrocytes were preloaded with DCF-DA for 30 min and washed with PBS. They were then pre-incubated for 2 h with various concentrations of Pi infusion. Then, ZnCl2 (50 μM) was added and the resulting fluorescence signal was measured at the indicated time points. The results represent means ± SEM of two experiments (n = 8). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 compared to cells treated with zinc alone.

To determine the time at which the Pi infusion best ameliorates H2O2-induced ROS production, the cells were pre-incubated with Pi infusion for 2 h or 1 h, cotreated or posttreated (for 2 h or 1 h) with H2O2. Interestingly, in contrast to the results obtained in our cell protection assay (Figure 3), the Pi infusion was similarly effective in attenuating ROS production when it was pre-incubated with the cells and when it was applied after the H2O2 (Figure 6). This may indicate that Pi treatment sets the cells into a defensive state that helps them to contend with oxidative stress and that it takes about 1 h to get the cells into that defensive state. If this is the case, it indicates that the Pi infusion not only is an antioxidant cocktail, but also contains compounds that might bind to a cell surface or intracellular receptor(s) to conduct a protective signal.

Figure 6.

Pi infusion is similarly effective in attenuating ROS production when applied before or after H2O2. Pi infusion (12.5 μg/mL) was added to astrocytes before (−2 h, −1 h) or after (1 h, 2 h) the addition of H2O2. ROS levels in DCF-DA preloaded astrocytes were measured 1, 4, and 6 h after the application of H2O2. The results are mean ± SEM of two experiments (n = 6). **P < 0.001.

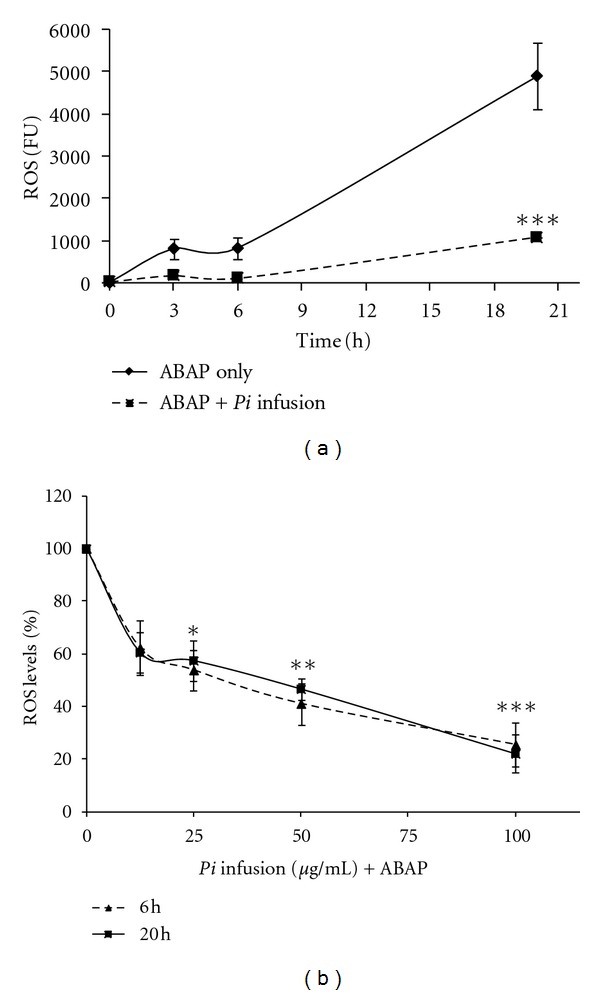

3.3. The Pi Infusion Reduced 2,2′-Azobis(amidinopropane)-(ABAP-) Mediated Peroxyl Radicals Levels in Astrocytes

In addition to H2O2, various other species, such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−), nitric oxide (NO•), and peroxyl radicals, have been found to oxidize DCFH to DCF in cell cultures [51]. Therefore, we used a cellular antioxidant activity assay to measure the ability of compounds present in the Pi infusion to enter the cells and prevent the formation of DCF by ABAP-generated peroxyl radicals [52]. The kinetics of DCFH oxidation in astrocytes by peroxyl radicals generated from ABAP is shown in Figure 7(a). As shown in that figure, ABAP generates radicals in a time-dependent manner and the treatment of cells with the Pi infusion moderated this induction. The increase in ROS-induced fluorescence was inhibited by the Pi infusion in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 7(b). This indicates that compounds present in the Pi infusion entered the cells and acted as efficient intracellular hydroperoxyl radical scavengers.

Figure 7.

Peroxyl radical-induced oxidation of DCFH to DCF in primary astrocytes and the inhibition of oxidation by the Pi infusion.(a) Astrocytes were incubated for 1 h with Pi infusion. Then, the astrocytes were preloaded with DCF-DA for 30 min and washed. ABAP (0.6 mM) was added to the culture and the fluorescence intensity representing ROS levels was measured. (a) The fluorescence levels of cells that had been preincubation with 100 μg/mL Pi extract were measured at the indicated time points. ***P < 0.001 compared to cells treated with ABAP only. (b) The fluorescence levels of cells that had been pre-incubated with various concentrations of Pi extract were measured at the indicated time points. The results represent means ± SEM of three experiments (n = 12). *P < 0.05,**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

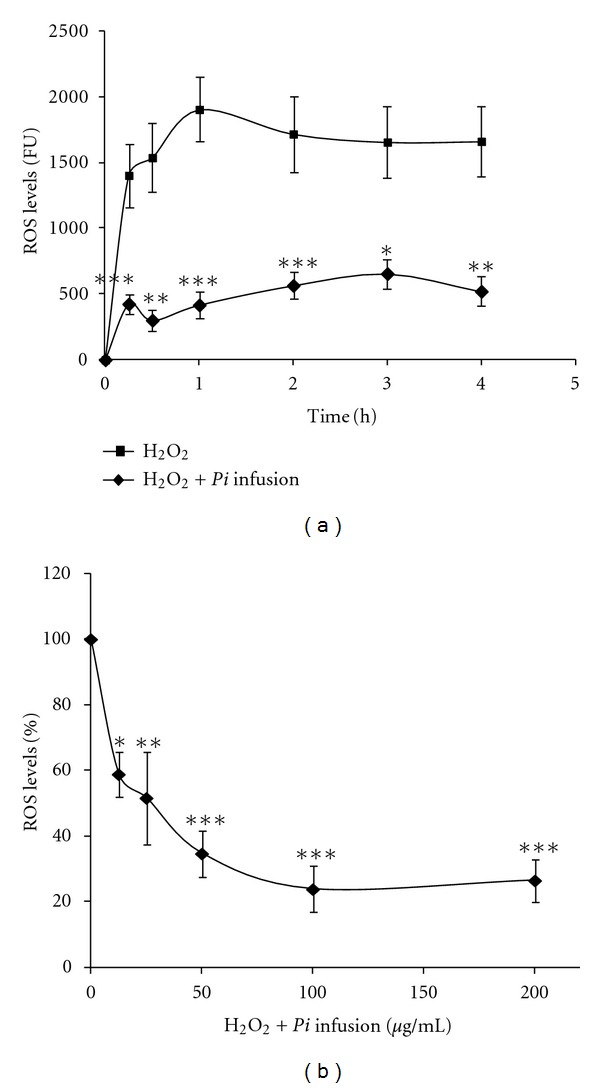

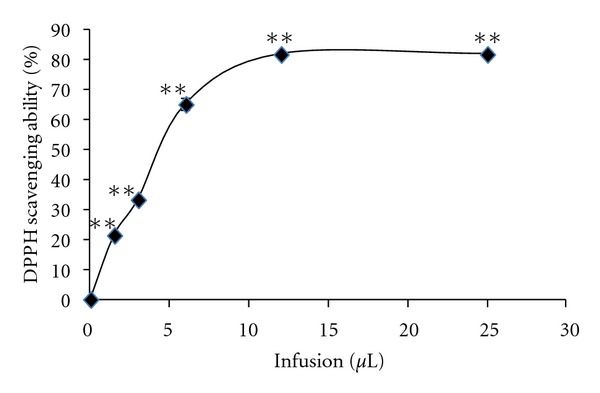

3.4. Free-Radical Scavenging Activity of Pi Infusion

Since many low molecular weight antioxidants may contribute to cellular antioxidant defense properties, we analyzed radical scavenging activity rather than seeking specific antioxidants. The free-radical scavenging activity of the Pi infusion was determined by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryhydrazyl (DPPH) radical which is considered to be a model lipophilic radical. In this assay, the Pi infusion was found to be a very potent free-radical scavenger with an IC50 value of 45 μg/mL and 80% inhibition of DPPH absorbance at 517 nm (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of the Pi infusion. The concentration of the infusion was 10 mg/mL. **P < 0.001.

3.5. The Pi Infusion Stimulated GDNF Expression in Astrocytes

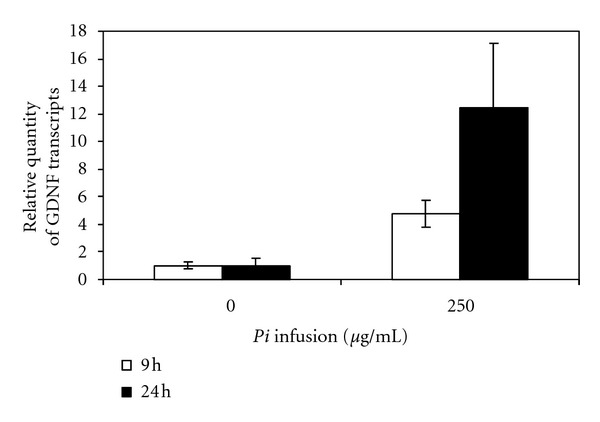

The contrast between the need for a preincubation of the cells with the infusion (Figure 3) in order to gain the protective effect and the fact that the timing of the addition of the Pi infusion did not appear to affect the ability of the treatment to neutralize ROS levels (Figure 6) led us to examine whether another factor aside from antioxidant activity might be involved in the beneficial effect of the Pi infusion. One possible factor could be GDNF secretion. It has been previously shown that GDNF protects astrocytes from ischemia-induced apoptosis [34]. Thus, we raised the possibility that the protective effect of Pi infusion on astrocytes suffering oxidative stress might be at least partially due to the induction of GDNF by the Pi infusion. This possibility might be supported by the need for preincubation of the Pi infusion with the cells in order to elicit the protective effect against H2O2-induced cell death. To test this possibility, we used real-time PCR and quantified GDNF mRNA. Primary astrocytes were treated with different concentrations of Pi infusion for several incubation periods and levels of GDNF transcripts were determined. The results of this work showed that incubation with Pi infusion at an optimal concentration of 250 μg/mL leads to a 5-fold increase in GDNF mRNA levels following 9 h of incubation and a 10-fold increase in GDNF mRNA levels following 24 h of incubation (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Treatment with the Pi infusion increases the levels of GDNF transcript in primary astrocytes. Rat primary astrocytes were exposed to 250 Mg/mL of Pi infusion for 9 or 24 h. Total RNA was then extracted. GDNF transcripts were measured using quantitative real-time PCR. The results of three technical replicates were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAPDH) and are expressed as relative quantities of GDNF transcripts. The results are means ± SD of one out of three experiments. Means-paired, one-tailed t-tests were used to evaluate the effects of the infusion on the expression of GDNF and the effect of the duration of the incubation. These tests yielded P(t) values of 0.029 and 0.105, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that, in cases in which the effect of the duration is not statistically significant, the effect of the Pi infusion is significant at a 95% significance level.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the effectiveness of the Pi infusion for counteracting oxidative damage in cultured astrocytes treated with hydrogen peroxide, zinc, or ABAP. The main findings of this study are that the examined Pi infusion can protect primary cultures of rat brain astrocytes from H2O2-induced cell death and reduce the levels of intracellular ROS produced following treatment with H2O2, ZnCl2, or ABAP. The beneficial effects of the Pi infusion are also demonstrated by the induction of astrocyte GDNF expression. Substances that can protect brain cells from oxidative stress are potential tools for the treatment of brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases. Specifically, the neurotrophic and protective effects of GDNF on neuronal cells that have been demonstrated in previous studies have made GDNF a promising candidate for gene and cell therapy for various neurodegenerative diseases [53–55].

H2O2 has been shown to induce the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, AKT/protein kinase B, and ATF-2 in C6 glioma cells [56]. The components of the Pi infusion might exert their protective effects by different mechanisms affecting one or more of these processes. Alternatively, or in addition, compounds present in the Pi infusion might act as signal-transduction agents to enhance the resistance of astrocytes to oxidative stress induced by ZnCl2 and H2O2, for example, by inducing the expression of neurotrophic factors such as GDNF or upregulating the expression of antioxidant stress-responsive genes such as glutathione S-transferase (GST).

The protective effect of the Pi infusion and the observed reduction in ROS levels might be mediated by its antioxidant activities, as was demonstrated by the DPPH experiment. Strong free-radical scavenging activity of a methanolic extract of Pi was also reported before [45, 57].

In our model, there are two opportunities for compounds present in the Pi infusion to elicit antioxidant effects. They can act at the cell membrane to disrupt peroxyl radical chain reactions at the cell surface or they can be taken up by the cell and react with ROS inside the cell. The efficiency of cellular uptake and/or membrane binding combined with that of the radical-scavenging activity dictate the efficacy of the tested infusion. In order to discriminate between these possibilities, astrocytes were pre-incubated with ABAP, which generates ROS inside cells. According to our results, the Pi infusion inhibited intracellular ROS levels, suggesting that, in addition to other possible activities, compounds present in the Pi infusion may enter the cells and react with ROS inside those cells.

The most popular traditional remedies are infusions or decoctions prepared from plants and herbs. These herbal teas are frequently used in the treatment of chronic diseases, such as cancer, gastrointestinal diseases, and type 2 diabetes. Scientific documentation is available regarding the functionality of herbal and tea extracts that contain different ingredients and have a wide variety of biological effects. For example, green tea (unfermented Camellia sinensis) contains large amounts of catechins and vitamin C, has anticancer effects [58], and protects against age-related neurodegeneration [59]. Oolong tea (semifermented Camellia sinensis) is known to be an effective treatment for allergic diseases [60] and the suppression of the accumulation of neutral fat [61]. Animal model studies with rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) and honeybush (Cyclopia intermedia) extracts indicate that teas prepared from both of these plants possess potent immune-modulating and chemopreventive activity [62]. Several other studies have revealed that some herbal medications and antioxidants show promise for the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases [63].

5. Conclusions

Neurodegenerative diseases are multifactorial and strategies for treating these diseases need to include a variety of interventions directed at multiple targets. On the basis of the current results, we suggest that various compounds present in the Pi infusion might have beneficial effects and should be further evaluated for the development of a health-promoting functional beverage for the prevention or treatment of brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases in which oxidative stress and astrocytic cell death play a role. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of Pi in the context of neurodegenerative diseases have not been studied previously and this is the first study to characterize the astroprotective effects of this plant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Science, Israel and by The Israel Science Foundation (Grant no. 600/08). The authors wish to thank Miriam Rinder (The Volcani center) Tatiana Rabinsky (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev) for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

Central nervous system

- GDNF:

Glial-derived neurotrophic factor

- Pi:

Pu li ca ri a incisa

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- DPPH:

2,2- Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- DCF-DA:

2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- ABAP:

2,2′-Azobis (amidinopropane).

References

- 1.Casetta I, Govoni V, Granieri E. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and neurodegenerative diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11(16):2033–2052. doi: 10.2174/1381612054065729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;97(6):1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyslop PA, Zhang Z, Pearson DV, Phebus LA. Measurement of striatal H2O2 by microdialysis following global forebrain ischemia and reperfusion in the rat: correlation with the cytotoxic potential of H2O2 in vitro . Brain Research. 1995;671(2):181–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01291-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Oxidative stress and nitration in neurodegeneration: cause, effect, or association? Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(2):163–169. doi: 10.1172/JCI17638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minghetti L. Role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2005;18(3):315–321. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000169752.54191.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floyd RA. Antioxidants, oxidative stress, and degenerative neurological disorders. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1999;222(3):236–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sastry PS. Lipids of nervous tissue: composition and metabolism. Progress in Lipid Research. 1985;24(2):69–176. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallgren B, Sourander P. The effect of age on the non-hem iron in the human brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1958;3(1):41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1958.tb12607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreck R, Baeuerle A. A role for oxygen radicals as second messengers. Trends in Cell Biology. 1991;1(2-3):39–42. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(91)90072-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dringen R, Pawlowski PG, Hirrlinger J. Peroxide detoxification by brain cells. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2005;79(1-2):157–165. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1758(8):994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaudry D, Pamantung TF, Basille M, et al. PACAP protects cerebellar granule neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;15(9):1451–1460. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero-Gutiérrez A, Pérez-Gómez A, Novelli A, Fernández-Sánchez MT. Inhibition of protein phosphatases impairs the ability of astrocytes to detoxify hydrogen peroxide. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;44(10):1806–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assaf SY, Chung SH. Release of endogenous Zn2+ from brain tissue during activity. Nature. 1984;308(5961):734–736. doi: 10.1038/308734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi DW, Koh JY. Zinc and brain injury. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1998;21:347–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Côté A, Chiasson M, Peralta MR, III, Lafortune K, Pellegrini L, Tóth K. Cell type-specific action of seizure-induced intracellular zinc accumulation in the rat hippocampus. Journal of Physiology. 2005;566(3):821–837. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Swiercz R, Englander EW. Elevated metals compromise repair of oxidative DNA damage via the base excision repair pathway: implications of pathologic iron overload in the brain on integrity of neuronal DNA. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;110(6):1774–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Hough CJ, Suh SW, Sarvey JM, Frederickson CJ. Rapid translocation of Zn2+ from presynaptic terminals into postsynaptic hippocampal neurons after physiological stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86(5):2597–2604. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frederickson CJ, Koh JY, Bush AI. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(6):449–462. doi: 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryu J, Shin C, Choi JW, et al. Depletion of intracellular glutathione mediates zinc-induced cell death in rat primary astrocytes. Experimental Brain Research. 2002;143(2):257–263. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EY, Koh JY, Kim YH, Sohn S, Joe E, Gwag BJ. Zn2+ entry produces oxidative neuronal necrosis in cortical cell cultures. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11(1):327–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YH, Kim EY, Gwag BJ, Sohn S, Koh JY. Zinc-induced cortical neuronal death with features of apoptosis and necrosis: mediation by free radicals. Neuroscience. 1999;89(1):175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim GW, Gasche Y, Grzeschik S, Copin JC, Maier CM, Chan PH. Neurodegeneration in striatum induced by the mitochondrial toxin 3-nitropropionic acid: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in early blood-brain barrier disruption? Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(25):8733–8742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08733.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop GM, Dringen R, Robinson SR. Zinc stimulates the production of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibits glutathione reductase in astrocytes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;42(8):1222–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danbolt NC. The high affinity uptake system for excitatory amino acids in the brain. Progress in Neurobiology. 1994;44(4):377–396. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barreto G, White RE, Ouyang Y, Xu L, Giffard RG. Astrocytes: targets for neuroprotection in stroke. Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;11(2):164–173. doi: 10.2174/187152411796011303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song H, Stevens CF, Gage FH. Astroglia induce neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells. Nature. 2002;417(6884):39–44. doi: 10.1038/417039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullian EM, Christopherson KS, Barres BA. Role for glia in synaptogenesis. Glia. 2004;47(3):209–216. doi: 10.1002/glia.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takuma K, Baba A, Matsuda T. Astrocyte apoptosis: implications for neuroprotection. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(2):111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Åkerud P, Alberch J, Eketjäll S, Wagner J, Arenas E. Differential effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and neurturin on developing and adult substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73(1):70–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke RE, Antonelli M, Sulzer D. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic growth factor inhibits apoptotic death of postnatal substantia nigra dopamine neurons in primary culture. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;71(2):517–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oo TF, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Regulation of natural cell death in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra by striatal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(12):5141–5148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05141.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. GDNF enhances the synaptic efficacy of dopaminergic neurons in culture. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(9):3172–3180. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu AC, Liu RY, Zhang Y, et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protects astrocytes from staurosporine- and ischemia-induced apoptosis. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2007;85(15):3457–3464. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robb SJ, Robb-Gaspers LD, Scaduto RC, Thomas AP, Connor JR. Influence of calcium and iron on cell death and mitochondrial function in oxidatively stressed astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1999;55(6):674–686. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990315)55:6<674::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feeney CJ, Frantseva MV, Carlen PL, et al. Vulnerability of glial cells to hydrogen peroxide in cultured hippocampal slices. Brain Research. 2008;1198:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu M, Hu LF, Hu G, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide protects astrocytes against H2O2-induced neural injury via enhancing glutamate uptake. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;45(12):1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakkali F, Averbeck S, Averbeck D, Idaomar M. Biological effects of essential oils—a review. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(2):446–475. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anekonda TS, Reddy PH. Can herbs provide a new generation of drugs for treating Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Research Reviews. 2005;50(2):361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solfrizzi V, Panza F, Capurso A. The role of diet in cognitive decline. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2003;110(1):95–110. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wengreen HJ, Munger RG, Corcoran CD, et al. Antioxidant intake and cognitive function of elderly men and women: the Cache County study. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2007;11(3):230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mansour RMA, Ahmed AA, Melek FR, Saleh NAM. The flavonoids of Pulicaria incisa . Fitoterapia. 1990;61(2):186–187. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleh NAM. Global phytochemistry: the Egyptian experience. Phytochemistry. 2003;63(3):239–241. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shabana MM, Mirhom YW, Genenah AA, Aboutabl EA, Amer HA. Study into wild Egyptian plants of potential medicinal activity. Ninth communication: hypoglycaemic activity of some selected plants in normal fasting and alloxanised rats. Archiv fur Experimentelle Veterinarmedizin. 1990;44(3):389–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abd El-Gleel W, Hassanien M. Antioxidant properties and lipid profile of Diplotaxis harra, Pulicaria incisa and Avicennia marina . Acta Alimentaria. 2012;41(2):143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amer MMA, Ramadan MF, Abd El-Gleel W. Impact of pulicaria incisa, diplotaxis harra and avicennia marina as hypocholesterolemic agent. Deutsche Lebensmittel-Rundschau. 2007;103(7):320–327. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stavri M, Mathew KT, Gordon A, Shnyder SD, Falconer RA, Gibbons S. Guaianolide sesquiterpenes from Pulicaria crispa (Forssk.) oliv. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(9):1915–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowry VW, Stocker R. Tocopherol-mediated peroxidation. The prooxidant effect of vitamin E on the radical-initiated oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1993;115(14):6029–6044. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niki E, Saito M, Yoshikawa Y, Yamamoto Y, Kamiya Y. Oxidation of lipids XII. Inhibition of oxidation of soybean phosphatidylcholine and methyl linoleate in aqueous dispersions by uric acid. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1986;59(2):471–477. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas MJ, Chen Q, Franklin C, Rudel LL. A comparison of the kinetics of low-density lipoprotein oxidation initiated by copper or by azobis (2-amidinopropane) Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1997;23(6):927–935. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1999;27(5-6):612–616. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolfe KL, Rui HL. Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) assay for assessing antioxidants, foods, and dietary supplements. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(22):8896–8907. doi: 10.1021/jf0715166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alberch J, Pérez-Navarro E, Canals JM. Neuroprotection by neurotrophins and GDNF family members in the excitotoxic model of Huntington’s disease. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002;57(6):817–822. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burton EA, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ. Gene therapy progress and prospects: Parkinson’s disease. Gene Therapy. 2003;10(20):1721–1727. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manabe Y, Nagano I, Gazi A, et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protein prevents motor neuron loss of transgenic model mice for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurological Research. 2003;25(2):195–200. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altiok N, Ersoz M, Karpuz V, Koyuturk M. Ginkgo biloba extract regulates differentially the cell death induced by hydrogen peroxide and simvastatin. NeuroToxicology. 2006;27(2):158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramadan MF, Amer MMA, Mansour HT, et al. Bioactive lipids and antioxidant properties of wild Egyptian Pulicaria incise, Diplotaxis harra, and Avicennia marina . Journal fur Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit. 2009;4(3):239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen ZP, Schell JB, Ho CT, Chen KY. Green tea epigallocatechin gallate shows a pronounced growth inhibitory effect on cancerous cells but not on their normal counterparts. Cancer Letters. 1998;129(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andrade JP, Assunção M. Protective effects of chronic green tea consumption on age-related neurodegeneration. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2012;18(1):4–14. doi: 10.2174/138161212798918986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sano M, Suzuki M, Miyase T, Yoshino K, Maeda-Yamamoto M. Novel antiallergic catechin derivatives isolated from oolong tea. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47(5):1906–1910. doi: 10.1021/jf981114l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han LK, Takaku T, Li J, Kimura Y, Okuda H. Anti-obesity action of oolong tea. International Journal of Obesity. 1999;23(1):98–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKay DL, Blumberg JB. A review of the bioactivity of South African herbal teas: rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) and honeybush (Cyclopia intermedia) Phytotherapy Research. 2007;21(1):1–16. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iriti M, Vitalini S, Fico G, Faoro F. Neuroprotective herbs and foods from different traditional medicines and diets. Molecules. 2010;15(5):3517–3555. doi: 10.3390/molecules15053517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]