Abstract

Background

MicroRNA (miRNA) alterations accompanying interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) in kidney allografts may point toward pathologic mechanisms. Small-RNA sequencing provides information on total miRNA abundance and specific miRNA expression, and allows analysis of differential expression based on read counts.

Methods

MiRNA expression profiles of 8 human kidney allograft biopsies (4 IFTA and 4 Normal biopsies, Discovery set) were characterized using barcoded deep-sequencing of a cDNA library prepared from multiplexed RNA. Statistical analysis of the sequence data guided selection of miRNAs for validation and the levels of selected miRNAs were quantified in 18 biopsies (10 IFTA and 8 Normal) using real-time quantitative PCR assays.

Results

Total miRNA content was 50% lower in RNA from IFTA compared to Normal biopsies. Global miRNA profiles clustered in partial agreement with diagnosis. Several miRNAs, including miR-21, 142-3p and 5p and the cluster comprising miR-506 on chromosome X had 2 to 7 fold higher expression in IFTA compared to Normal biopsies, whereas miRNA miR-30b and 30c were lower in IFTA biopsies (miR-30a, -30d, -30e and all respective star sequences showed similar trends). IFTA and Normal biopsy distinction was also noted in the pattern of miRNA nucleotide sequence variations. Differentially expressed miRNAs were confirmed on the larger set of allograft biopsies using RT-QPCR and the levels of miRNAs were found to be associated with allograft function and survival.

Conclusions

Differentially expressed miRNAs and their predicted targets identified by deep sequencing are candidates for further investigation to decipher the mechanism and management of kidney allograft fibrosis.

Keywords: biomarkers, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, kidney transplantation, microRNA, next generation sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation is remarkably successful in the short-term but almost 50% of the grafts fail by 10 years (1). Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) is a common histologic feature of kidney grafts failing beyond the first year of transplantation (2, 3). A better understanding of mechanisms involved in IFTA may lead to the development of targeted and safer therapeutic modalities.

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are evolutionarily conserved ~22 nucleotide RNAs that repress protein-coding genes by guiding the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) (4). miRNAs play critical roles in diverse biological processes. Currently more than 500 human miRNAs are known (5). A number of studies have described altered miRNA expression in native and allograft kidney diseases (6–17). In organ fibrosis, miRNAs are regulated by transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) and in turn, regulate TGFβ signaling components. Thus, feed-forward loops may result from release of miRNA inhibition on the TGFβ pathway (18).

We recently reported that urinary cell levels of mRNAs encoding proteins implicated in fibrogenesis and mRNA encoding renal tubule epithelial cell specific protein NKCC2 are associated with IFTA, and that a 4-gene signature of mRNAs for VIM, SLC12A1 (NKCC2), CDH1 (E-Cadherin) and 18S ribosomal RNA is diagnostic of allograft fibrosis (19). However the mechanistic basis of alterations in mRNA expression in fibrosis remains unclear. As miRNAs regulate mRNAs, we investigated whether IFTA is associated with altered intragraft miRNA expression, and whether miRNA profiles distinguish IFTA biopsies from normal allograft biopsies. To address this question we applied small-RNA sequencing to catalogue and characterize the miRNA transcriptome of human kidney allografts with or without fibrosis.

In this proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate the feasibility of a novel barcoded (multiplexed) miRNA sequencing protocol on human kidney allograft biopsies with or without fibrosis, validate differential expression of miRNAs using an independent cohort, associate miRNA levels with allograft function and outcome, and advance the potential of miRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of human renal allografts.

RESULTS

Study Cohort

We studied 26 kidney allograft biopsy samples from 26 kidney-transplant recipients who underwent either clinically indicated biopsies (n=9) or surveillance (protocol) biopsies (n=17) (Table 1). Eight biopsies from 8 recipients (4 IFTA and 4 Normal) were used for global miRNA profiling by small RNA sequencing and served as the Discovery set. The remaining 18 biopsies from 18 recipients (10 IFTA and 8 Normal) served as the independent Validation cohort and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-QPCR) assays were used to measure the miRNAs discovered by sequencing to be differentially expressed.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of kidney-transplant recipients and donors

| Characteristics | IFTA Biopsy Group N=14 |

Normal Biopsy Group N=12 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Recipient Gender | ||

| Male | 6 | 8 |

| Female | 8 | 4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 5 | 4 |

| White | 2 | 3 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 3 |

| Others | 3 | 2 |

| Age at biopsy, years, mean (SD)a | 49 (13) | 49 (12) |

| Multiple transplants | 1 | 0 |

| Type of donor kidney | ||

| Deceased | 8 | 8 |

| Living | 6 | 4 |

| Donor gender | ||

| Male | 7 | 7 |

| Female | 7 | 5 |

| Donor race | ||

| Black | 1 | 3 |

| White | 8 | 5 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 3 |

| Others | 3 | 1 |

| Donor age, years, mean (SD) | 48 (7) | 40 (12) |

| Time from transplant to biopsy, months, median (IQR)b | 29 (51) | 4 (12) |

| Biopsy indication | ||

| Protocol | 5 | 12 |

| For-cause | 9 | 0 |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | ||

| Corticosteroids-based | 6 | 0 |

| Not corticosteroids-based | 8 | 12 |

| Creatinine at biopsy, mg/dl, median (IQR) | 2.35 (1.60) | 1.35 (0.85) |

| Banff diagnostic categoryc | ||

| 1 / 2 / 5 | 0 / 5 / 9 | 12 / 0 / 0 |

| Banff IFTA graded | ||

| I / II / III | 3 / 9 / 2 | 0 / 0 / 0 |

Standard deviation.

Inter-quartile range.

Banff ‘07 Classification – 1, normal allograft biopsy findings; 2, Antibody mediated changes; 5, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, no evidence of any specific etiology. Five of the 14 IFTA biopsies showed changes consistent with chronic active antibody mediated rejection.

Grade I, mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (<25% of cortical area); II, moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (26–50% of cortical area); III, severe interstitial fibrosis (>50% of cortical area)

Preparation of barcoded small-RNA cDNA libraries and small RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from 4 Normal and 4 IFTA biopsies (see Supplemental Digital Content [SDC], Table S1) and subjected to barcoded cDNA library preparation. The sequence library contained 2.1 million sequence reads with ~250,000 unique reads. The median number of redundant reads per sample was 2.5×105 (IQR 1.5×105–3.1×105). One sample, from an IFTA biopsy (M2), collected only 11,000 reads (accompanied by a similar reduction in calibrator reads, thus presumably due to suboptimal 3′-ligation reaction due to residual genomic DNA or salt from RNA isolation). This sample was excluded from statistical analyses due to too very few reads (there was no RNA for repeat sequencing).

Major classes of small-RNA annotations were miRNA 64%; synthetic calibrator 26%; rRNA 4%; and ‘none’ 3% (positive matching to genome but absence of annotation). Calculated miRNA content in input RNA was 7.7±1.3 and 4.0±1.8 fmol per μg total RNA in Normal and IFTA samples, respectively (P=0.027, Table S2). None of the small-RNAs with annotation ‘none’ were expressed over 300 reads per million miRNA reads, suggesting that our current miRNA annotation did not miss any reasonably abundant unrecognized miRNA. Inserts that mapped to the human genome but not assigned annotation are presented in Table S3.

Intragraft MicroRNA expression profile analysis

Reads with miRNA annotation were grouped according to 3 different schemes (Tables S4, S5 (5)); (i) mature miRNA with multiple genomic copies were merged into single entries (e.g., reads originating from miR-9-1, miR-9-2 and miR-9-3 were collapsed into a single entry, miR-9(3) – the number in parenthesis representing the number of merged genes); (ii) reads of mature miRNA and miRNA* originating from pri-miRNA cistronic transcripts were merged into precursor clusters; and (iii) miRNA reads were grouped by families according to sequence similarities.

Differential expression of miRNAs in the discovery set of IFTA and Normal biopsies

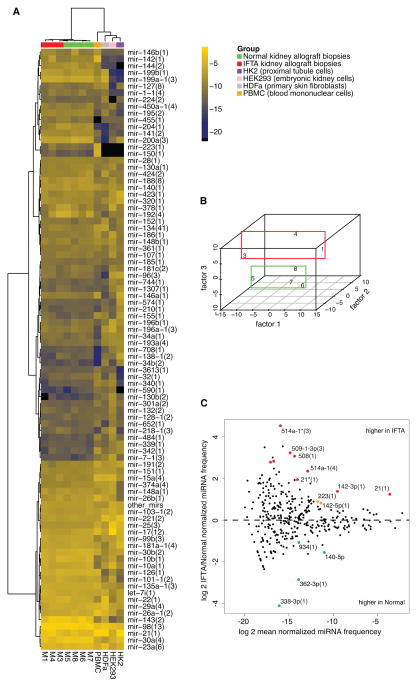

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and heatmap representation of intragraft miRNA profiles generated by small RNA sequencing of kidney allograft biopsy samples according to merged miRNA profiles are shown in Figure 1A. MiRNA profiles of HK2 cells (kidney proximal tubule cells), HEK293 cells (human embryonic kidney cells), HDFa (primary skin fibroblast) and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are also shown in Figure 1A for comparison. MiRNAs represented by fewer than 100 reads per sample (average) were collapsed into a single entry (‘other mirs’) in the heatmap. Figure 1B shows multidimensional scaling separation of IFTA samples from Normal samples by the third factor. Figure 1C shows the MA plot, generated using DESeq, depicting differentially expressed miRNA sequence families in IFTA samples and Normal samples. Both unsupervised hierarchical clustering and multidimensional scaling of samples (Figure 1A and 1B) was insensitive to the three methods (listed above) used to group miRNAs.

Figure 1. MicroRNA profiles generated by small RNA sequencing.

(A) Hierarchical clustering and heatmap representation of kidney allograft IFTA biopsy samples (M1, 3 and 4), Normal biopsies (M5, 6, 7 and 8), human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), HDFa (primary skin fibroblast), HEK293 cells (human embryonic kidney cells) and HK2 cells (kidney proximal tubule cells) according to merged miRNA profiles (average linkage, Manhattan distance). MiRNA represented by fewer than 100 reads per sample (average) were collapsed into a single entry (‘other mirs’). Brighter shades represent higher expression, according to the color scheme shown on the side, in which the numbers correspond to the log-2 of the normalized read frequency (for example, −4 on the scale corresponds to 2−4 = 6.25% of all miRNA reads). (B) Multidimensional scaling showing separation of IFTA biopsies from Normal biopsies by the third factor. (C) MA plot generated using DESeq depicting differentially expressed miRNA sequence families. MiRNA higher in IFTA samples appear above the horizontal midline. Colored data points represent P-value < 0.05 (red points signify in addition FDR<0.1). See also Table S6.

Table 2 displays differentially expressed miRNAs detected at false detection rate (FDR) <0.1 (Table S6 lists all differentially expressed miRNA with nominal P-value<0.05). Among the most abundant miRNAs, miR-21 was expressed higher in IFTA biopsies (2.3-fold increase, at FDR<0.01), while miR-30b (3-fold) and miR-30c(2) (2-fold) were higher in Normal biopsies (similar trends were noted for all other miR-30 family members and star sequences).

Table 2.

Differential expression of miRNAs, miRNA cistronic clusters and miRNA sequence families at false detection rate < 0.1 (differential expression of miRNAs at nominal P-value < 0.05 are presented in Table S6) in discovery cohort biopsies

| miRNA, miRNA cistronic cluster or miRNA sequence family | Normalized miRNA read frequency | Fold change | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=4) | IFTA (n=3) | |||

|

| ||||

| Merged miRNA | ||||

| miR-21 | 3.6% | 8.4% | 2.3 | 0.006 |

| miR-142-3pa | 0.068% | 0.18% | 2.6 | 0.012 |

| miR-514a(3) | 0.0044% | 0.023% | 5.3 | <0.0001 |

| miR-21* | 0.0026% | 0.010% | 3.9 | 0.012 |

| miR-508 | 0.0011% | 0.0095% | 8.4 | <0.0001 |

| miR-509-3p(3) | 0.0007% | 0.0070% | 9.4 | <0.0001 |

| miR-506 | 0.0002% | 0.0015% | 7.1 | 0.074 |

| miR-514a*(3) | 0.0002% | 0.0042% | 24 | <0.0001 |

| miR-509-5p(2) | 0 | 0.0013% | inf. | 0.006 |

| miRNA cistronic clusters | ||||

| cluster-mir-21(1) | 3.4% | 8.2% | 2.4 | 0.006 |

| cluster-mir-142(1) | 0.087% | 0.21% | 2.4 | 0.077 |

| cluster-mir-506(11) | 0.0065% | 0.044% | 6.7 | <0.0001 |

| miRNA sequence families | ||||

| sf-miR-21(1) | 3.4% | 8.1% | 2.4 | 0.008 |

| sf-miR-142-3p(1) | 0.064% | 0.17% | 2.6 | 0.026 |

| sf-miR-514a-1(4) | 0.0044% | 0.022% | 5.1 | <0.0001 |

| sf-miR-21*(1) | 0.0024% | 0.0093% | 3.8 | 0.010 |

| sf-miR-508(1) | 0.0010% | 0.0088% | 8.4 | <0.0001 |

| sf-miR-509-1-3p(3) | 0.0006% | 0.0060% | 9.9 | <0.0001 |

| sf-miR-509-1-5p(3) | 0.0003% | 0.0018% | 7.0 | 0.026 |

| sf-miR-506(1) | 0.0002% | 0.0015% | 6.9 | 0.085 |

| sf-miR-514a-1*(3) | 0 | 0.0035% | inf. | <0.0001 |

miR-142-5p was also higher in IFTA biopsy samples, see Table S6.

Analysis of sequence variation in miRNA

Nucleotide variation found in deep sequencing data can represent SNP, somatic mutation, RNA editing (deamination, 3′-uridylation, 3′-adenylation), sequencing error or mapping error. Following previously established analysis of nucleotide variation in a deep-sequencing data (5) we identified 33 distinct nucleotide variations (Table 3). C>T variation in miR-196a-2 appears to be a known SNP (rs11614913) and A>G changes in mature sequence of miR-376a/c likely represent A-to-I editing by dsRNA-specific adenosine deaminase (5, 21, 22). Variation was noticeably more common in the 3′-end of mature/star sequences, showing changes compatible with adenylation and uridylation. The latter alterations were more frequent in IFTA compared to Normal biopsies.

Table 3.

MiRNA sequence variations in discovery cohort biopsies

| Position | IFTA librariesc | Normal librariesc | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| MiRNA precursor | Region | Genomic coordinates | Pos.a | Pos.b | Change | Comment | M1 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| mir-376c | mature | 14:101506074:+ | 53 | 6 | A>G | editingd | ND | 0.722 | 0.840 | 0.667 | 0.619 | 0.471 | 0 |

| mir-376a-1 | mature | 14:101507167:+ | 53 | 6 | A>G | editingd | ND | ND | 0.958 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ND | ND |

| mir-376a-2 | mature | 14:101506460:+ | 53 | 6 | A>G | editingd | ND | ND | 0.958 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ND | ND |

| mir-215 | mature | 1:220291259: − | 30 | 20 | A>C | ND | 0.615 | ND | 0.766 | ND | 0 | 0 | |

| mir-196a-2 | star | 12:54385599:+ | 64 | 18 | C>T | rs11614913 | ND | ND | ND | 0.909 | ND | ND | ND |

| mir-143 | 3p | 5:148808562:+ | 66 | 1 | A>T | 0.346 | 0.345 | 0.336 | 0.338 | 0.365 | 0.332 | 0.347 | |

| mir-151 | 3p | 8:141742684: − | 69 | 2 | C>A | 0.579 | 0 | 0.579 | 0.618 | 0.739 | 0.588 | 0.524 | |

| mir-92a-1 | 3p | 13:92003637:+ | 70 | 1 | T>A | ND | 0.611 | 0.490 | 0.469 | 0.431 | 0.518 | 0.608 | |

| mir-24-1 | 3p | 9:97848368:+ | 71 | 1 | G>T | 0.556 | 0 | 0.519 | 0.469 | 0.522 | 0.485 | 0.568 | |

| mir-378 | 3p | 5:149112452:+ | 71 | 1 | C>A | 0 | 0.536 | 0.481 | 0.589 | 0.619 | 0.727 | 0.579 | |

| mir-92a-2 | 3p | X:133303573: − | 72 | 1 | G>A | ND | 0.786 | 0.714 | 0.852 | 0.920 | 0.878 | 0.835 | |

| mir-199a-2 | 3p | 1:172113693: − | 72 | 2 | G>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.442 | 0.488 | 0.415 | |

| mir-24-2 | 3p | 19:13947102: − | 71 | 1 | G>T | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.364 | 0.392 | 0.394 | |

| mir-423 | 3p | 17:28444172:+ | 70 | 1 | C>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.500 | 0.706 | 0 | 0 | |

| mir-324 | 3p | 17:7126626: − | 68 | 1 | G>T | ND | ND | ND | 0 | 0 | ND | 0.667 | |

| mir-125b-2 | 3p | 21:17962634:+ | 72 | 1 | A>T | ND | ND | 0 | 0 | 0.684 | 0 | 0 | |

| mir-148b | 3p | 12:54731084:+ | 72 | 1 | C>T | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| mir-27a | 3p | 19:13947260: − | 73 | 1 | C>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.336 | 0 | 0 | |

| let-7c | loop | 21:17912180:+ | 33 | 1 | T>A | 0.278 | 0.245 | 0.203 | 0.149 | 0.158 | 0.164 | 0.149 | |

| let-7i | loop | 12:62997493:+ | 33 | 1 | G>A | 0.410 | 0.356 | 0.346 | 0.376 | 0.376 | 0.298 | 0.314 | |

| mir-143 | loop | 5:148808528:+ | 32 | 1 | T>A | 0 | 0.202 | 0.206 | 0.274 | 0.245 | 0.410 | 0.307 | |

| mir-26a-2 | loop | 12:58218440: − | 33 | 1 | G>T | 0 | 0.383 | 0.253 | 0.365 | 0.403 | 0.300 | 0.225 | |

| mir-26a-1 | loop | 3:38010926:+ | 33 | 1 | G>T | 0 | 0 | 0.242 | 0.360 | 0.366 | 0.254 | 0.211 | |

| mir-125b-1 | loop | 11:121970516: − | 33 | 1 | T>A | ND | 0.920 | 0.571 | 0.698 | 0.576 | 0 | 0.627 | |

| mir-125b-2 | loop | 21:17962595:+ | 33 | 1 | G>A | ND | 1.000 | 0.690 | 0.909 | 0.704 | 0 | 0.914 | |

| mir-194-1 | loop | 1:220291547: − | 33 | 1 | C>A | ND | 0 | ND | 0.738 | ND | 0.786 | 0 | |

| mir-26a-1 | loop | 3:38010926:+ | 33 | 1 | G>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.208 | 0 | 0.261 | 0.154 | |

| mir-99a | loop | 21:17911443:+ | 33 | 2 | G>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.368 | 0.212 | 0 | 0 | |

| let-7b | loop | 22:46509594:+ | 34 | 2 | C>T | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.295 | 0 | 0 | 0.180 | |

| mir-143 | loop | 5:148808538:+ | 42 | 11 | G>A | ND | ND | 0 | 0 | 0.526 | ND | ND | |

| mir-100 | loop | 11:122022982: − | 33 | 1 | G>A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| mir-200b | loop | 1:1102537:+ | 44 | 12 | C>A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.000 | ND | |

| mir-21 | 5p | 17:57918633:+ | 10 | 10 | G>C | ND | 0 | 0.475 | 0 | 0.417 | 0 | 0.396 | |

33 distinct nucleotide variations were identified, 5 of which were located in mature/star miRNA sequences, 1 in a 5′ region, 14 in loops and 13 in the 3′ regions of a precursor.

Position in the entire precursor follows our previously published definitions (5).

Position within the specific sub-region of the precursor follows our previously published definitions (5).

Numbers denote the ratio of varied divided by total reads at the indicated position; ND denotes sequence coverage insufficient to analyze (< 10 reads with the respective position)

A->G changes in mature sequence of miR-376a-1, mir-376a-2 and mir-376c are likely representing A to I RNA editing by dsRNA-specific adenosine deaminase. This specific editing event and its effect on targeting have been previously described (21, 22), and is supported by a well-represented unimodal distribution of the nucleotide variation frequency from a previous study (5).

MicroRNA target identification with PAR-CLIP

Of the differentially expressed miRNAs, 2 sequence families showed expression exceeding 0.1% of total miRNA reads in either patient group, suggesting they may be causally and traceably involved in the fibrotic process: miR-21 (8.1% in IFTA samples, 2.4-fold over Normal) and the myeloid/lymphoid-lineage specific miR-142-3p (0.2% in IFTA samples, 2.6-fold over Normal). Inspection of kidney miRNA profiles in relation to profiles obtained from kidney cell-lines, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and cultured fibroblasts (Figure 1A) suggested that occurrence of miR-142-3p in IFTA samples is due to leukocyte infiltration, whereas miR-21 is likely upregulated in kidney parenchymal cells. Notably, miR-223 (expressed in monocytes > lymphocytes), miR-150 (expressed in lymphocytes) and miR-155 (expressed in lymphocytes > monocytes) (23) were also more abundant in IFTA biopsies (1.9, 2.3 and 1.8-fold respectively), but variability was higher. MiR-199a/b, moderately expressed in fibroblasts, appeared to have lineage-specificity (i.e., were absent in kidney cell-lines and not of vascular lineage) that could potentially impact on the tissue miRNA profile. However, miR-199a and miR-199b were not differentially expressed between IFTA and Normal samples. We thus focused on miR-21, and searched for possible targets among transcripts that were coimmunoprecipitated with proteins Argonaute 1–4 (EIF2C1-4). We queried a published dataset of mRNA clusters from pooled PAR-CLIP experiments on FLAG/HA-tagged Argonaute proteins in human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells (24) for miR-21 binding sites. Using in-house search algorithms we found enrichment for 7-mer (ATAAGCT) and 8-mer (GATAAGCT) seed-complementary sequences of miR-21 (both P<0.05). PAR-CLIP clusters harboring these sites are listed in Table S8. An example of a miR-21 target identified in this manner, SMAD7, is illustrated in Figure S1.

Differential expression of miRNAs in the validation set of IFTA and normal biopsies

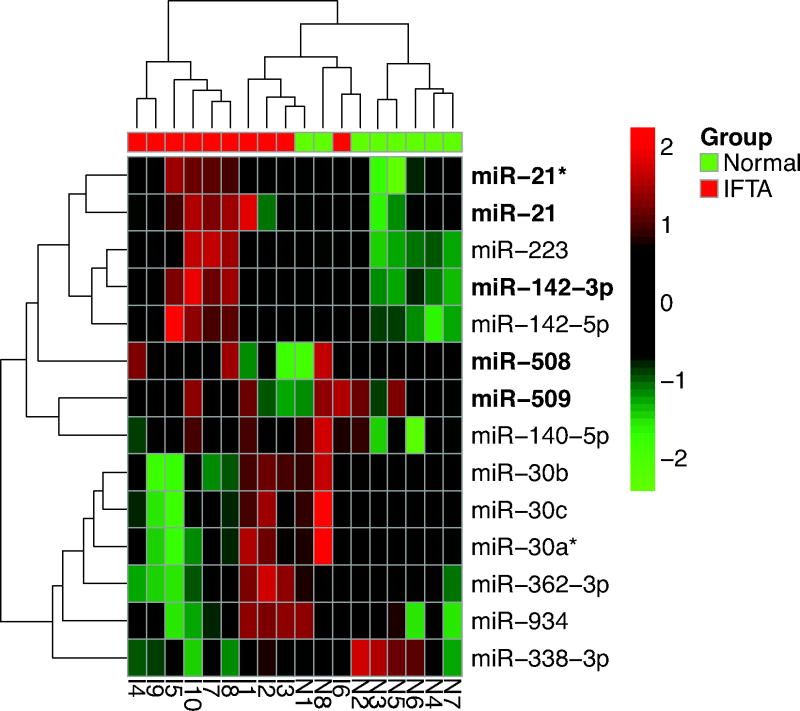

An independent cohort of 18 kidney-transplant recipients (10 IFTA and 8 Normal) was used to validate the differential expression of miRNAs discovered by small RNA sequencing (Table 2). We used our previously described RT-QPCR standard curve method for the quantification of absolute levels of intragraft miRNAs (15). Of the 14 miRNAs chosen based on differential sequence counts, significant differences in the levels were found in 8 miRNAs, including confirmation of increased levels of miR-21/miR-21*, miR142-3p/miR-142-5p and miR-223 in IFTA biopsies, and decreased levels of mir-30a family members (Table S7). Furthermore, unsupervised clustering according to RT-QPCR copy numbers of all assayed miRNAs clearly followed disease classification (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Unsupervised Hierarchical Clustering of miRNA in the Validation Cohort.

RT-QPCR levels of miRNA in kidney allograft biopsies of kidney-transplant recipients were subjected to unsupervised hierarchical clustering (complete linkage, Manhattan distance). MiRNA copies (per μg total RNA) were determined by the standard curve method on an ABI Prism 7700 system in kidney allograft biopsy tissue obtained from 10 subjects with IFTA biopsies and 8 subjects with Normal biopsy results, and were normalized across the rows. Levels of RNU6B (U6), a small nuclear RNA used as endogenous control, did not differ across the groups and was not included in the clustering. See Table S7 for miRNA absolute copy numbers ascertained by RT-QPCR.

Small RNA sequencing and the RT-QPCR protocol used in this study provided information regarding absolute abundance of miRNAs. Among the miRNAs quantified with both techniques, we found a fair agreement between standard curve-derived copy numbers and small-RNA sequencing read counts (r=0.53 with miR-509-1-3p excluded). We found using linear regression that in Normal biopsy samples, a normalized read count of 1% corresponds to 1×107 copies per μg total RNA by RT-QPCR assay. Considering that in Normal samples global miRNA content according to sequencing was 7.7 fmol per μg total RNA, 1% represents 0.077 fmol or 4.6×107 molecules per μg total RNA. One exception to the reasonable agreement between the two platforms was miR-509-1-3p, which was determined to be several orders of magnitude more abundant according to RT-QPCR compared to sequencing. Together with the lack of concordance between small RNA sequencing and RT-QPCR assay regarding differential expression of miR-509-1-3p, the discrepancy might point to mispriming/misprobing associated with the RT-QPCR assay for this specific miRNA. MiR-21, on the other hand, collected more sequence reads than expected from RT-QPCR-derived copy numbers. Notwithstanding possible differences between the study cohorts evaluated by RNA sequencing and RT-QPCR, the greater abundance of miR-21 is in agreement with a previously published ligation bias associated with miR-21 (ligation biases are listed in supplementary Table S6) (20).

MiRNAs and clinical variables in the validation cohort

Time from kidney transplantation to biopsy was longer in the IFTA group compared to Normal biopsy group (Mann-Whitney, P=0.005). There was a positive association between time to biopsy and the levels of miR-142-3p/5p, miR-223, miR-508, miR-21* and an inverse association with the levels of miR-362-3p, miR-338-3p, miR-30b, miR-30c (Spearman rs, P<0.05). After adjustment for biopsy diagnosis (IFTA vs. Normal), the associations between the time to biopsy and levels of miR-21, miR-21*, miR-142-3p/5p and miR-223 was not significant in the full validation cohort (GLM, P-values>0.1), whereas the relationship between time-to-biopsy and miR-30b/c was significant only within the IFTA subgroup (P<0.05)

Rate of prednisone use, but not other immunosuppressive medications, was higher in the IFTA subgroup (5/10 vs. 0/8 in the Normal subgroup, P=0.036). Expression levels of several miRNAs (increased: miR-21, miR-21*, miR-142-3p/5p and miR-223; decreased: miR-362-3p, miR-338-3p, miR-30a-3p, miR-30c and miR-30b) were linked with prednisone use (Mann-Whitney, P<0.05). However, these associations were abolished by adjustment for histological diagnosis, except miR-223, which remained increased in prednisone users after adjustment for histological diagnosis (GLM, P=0.039). MiR-142-3p/5p, miR-223 and miR-21* remained significantly increased in IFTA biopsies after adjustment for prednisone use.

MiR-21, miR-21*, miR-142-3p and miR-934 were linked with donor type (living vs. deceased). After adjusting for the type of donor kidney, miR-21, miR21*, miR-142-3p/-5p and miR-223 (higher in IFTA) and miR-338-3p (lower in IFTA) were still significantly associated with patient group (IFTA vs. Normal, multivariate GLM, P<0.05). Nine of the 14 IFTA biopsies were classified as IFTA with no specific etiology (Banff category 5) and the remaining 5 IFTA biopsies showed additional histological changes consistent with chronic active antibody mediated rejection (Banff category 2, Chronic active AMR+IFTA+). The miRNAs that were differentially expressed in IFTA biopsies and Normal biopsies were not different between chronic AMR+IFTA+ and IFTA group without chronic active AMR. Interestingly, miR-199a/b, not differentially expressed between IFTA and Normal biopsies, were ~2-fold higher in the IFTA alone group compared to IFTA plus chronic active AMR group (P<0.01).

Differentially expressed miRNAs and clinical outcomes in the validation set

When kidney transplant recipients were divided into two groups based on the median level of miRNAs, allograft survival was significantly inferior in those with above median levels of the following miRNAs: miR-21 (P=0.03), miR-21* (P=0.02), miR-142-3p (P=0.02), miR-142-5p (P=0.02) and miR-223 (P=0.02), and with below median levels of miR-30b (P=0.02) and miR-30c (P=0.02). The slope of the reciprocal of serum creatinine over 6 months and 36 months after biopsy was significantly associated with the levels of miR-142-3p (rs=−0.49 at 6 months and −0.73 at 36 months), miR-142-5p (rs=−0.57 and −0.77), and miR-223 (rs = −0.53 and −0.59) (all P-values <0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this first study of human kidney allograft biopsy miRNA sequencing, we profiled 4 normal and 4 IFTA kidney allograft specimens by small RNA sequencing, and validated differential expression of miRNAs by RT-QPCR assaying of 10 IFTA and 8 normal allograft biopsies from 18 patients. Sequencing can detect previously unrecognized molecules and sequence variants of known transcripts, e.g., polymorphism and editing, allowing us to exclude the possibility of an abundant yet previously unrecognized kidney miRNA and also report on miRNA editing in kidneys, with altered adenylation/uridylation pattern in IFTA (the causes and consequences of which require further study); it can differentiate between highly similar transcripts; and transcriptome-wide quantification is possible by spiking external calibrator oligoribonucleotides. We overcame and even overturned potential disadvantages, such as cumbersome preparation protocols and high costs, by multiplexing, i.e. pooling RNA specimens such that most preparative steps and the sequencing reaction were performed on a single library containing multiple source samples. Our overall sequencing depth and the number of reads were similar across the samples, indicating that multiplexing did not compromise subsets of samples.

Total miRNA content was 1.9-fold lower in IFTA allograft RNA compared to Normal samples. This finding has implications on quantitative analysis of differential expression, and it is of interest to evaluate whether this reflects a general phenomenon. Neal and colleagues have reported ~2-fold lower miRNA content, and possibly lower miRNA stability, in uremic plasma (25). Conceivably, the kidneys could be major contributors to the circulating miRNA pool, and the decreased circulating miRNA in uremia might reflect reduced renal mass. Alternatively, uremic toxins may inhibit in-vivo miRNA biogenesis or miRNA detection in-vitro. Both are inline with our finding of decreased miRNA content in IFTA RNA (IFTA patients in the Discovery cohort had lower kidney function at baseline). In addition, miRNA content in rat organs (kidney, thyroid and liver) was found to be 1.8-fold lower in early-stage CKD compared to healthy rats (P=0.01; Ben-Dov IZ, unpublished). We cannot however rule out the possibility that differences in cellular content between IFTA biopsies and Normal biopsies contributed to the observed difference identified in the current study (as well as to differences in specific miRNA as detailed below).

Analysis of miRNA expression pattern in IFTA samples and normal samples revealed 16 mature and star miRNAs, arranged in 3 precursor clusters that were significantly different at a FDR<0.1. RT-QPCR assaying of a larger set of patient samples recaptured the differential miRNA expression pattern. This independent confirmation is important in light of the absolute differences noted in total miRNA content between Normal and IFTA allografts. It is noteworthy that compared to a recent report of miRNA expression in allograft fibrosis (26), the differences in miRNA expression between IFTA samples and normal samples in our study were more modest both in diversity and magnitude. Differences in the characteristics of the patients studied, allograft pathology and/or assay platforms used to evaluate miRNA expression may have contributed to differences between our study and the earlier report (26). Scian and colleagues employed hybridization/PCR-based arrays requiring polyadenylation of input RNA for cDNA generation (26), while we subjected total RNA to ligation-based small-RNA sequencing of a barcoded cDNA library. Overestimation of differential expression by procedures employing hybridization may be due to greater batch effects compared to sequencing, and to lower discrimination between closely related miRNAs (27). The latter may lead to false positive hybridization of a highly-expressed miRNA to a low-expressed miRNA probe. Conversely, barcoded small-RNA profiling may mask the true magnitude of differential expression due to barcode-related ligation biases (28). We have shown however that our 3′ adapter-based sample indexing, rather than 5′-adapter barcodes (28), does not introduce barcode biases (5, 20). Notwithstanding the above discussion, miRNAs discovered in the current study were associated with IFTA biopsy histology independent of clinical patient characteristics and predicted clinically relevant allograft outcome.

Querying a dataset of mRNA captured by Argonaute IP from HEK293 cells served as an alternative to genome-wide target prediction, affording enhanced specificity. We confirmed SMAD7 among the biochemically identified miR-21 targets. SMAD7 has been shown to inhibit TGFβ fibrotic effects on tubular epithelial cells by blocking SMAD2 activation (29). It will be worthwhile to examine whether increase in miR-21, in itself upregulated by SMAD3 (30), directly decreases SMAD7 levels thus contributing to this fibrogenic pathway. MiR-21 expression is under complex regulatory mechanisms involving a unique promoter, several transcription factors and hormones and signaling events (31). It is upregulated in a wide variety of tumors and cardiovascular disorders, where it promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and prevents apoptosis (31, 32). In murine cardiac fibroblasts, miR-21 overexpression was noticed in response to stress or infarct (33). MiR-21 antagonists applied for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis in pressure-overloaded mice inhibited interstitial fibrosis and improved cardiac function (34). In animal models of kidney fibrosis, existing communications present conflicting evidence for miR-21 as either a bystander (35) or having a causative role in the pathogenic process (30). Our finding of increased miR-21 expression in human allograft fibrosis highlights the need to delineate disease processes affected by miR-21. It should be noted that miR-21 has relatively few validated targets, possibly due to AU-rich seed sequence interactions. For perspective, the ratio between miRTarBase-reported, experimentally-verified targets (36) and total PubMed publications is 0.09 for miR-21; 0.40 for let-7; 0.49 for miR-16; 0.58 for miR-15a/b; 0.55 for miR-30a-e; 0.21 for miR-122 and 0.08 for miR-10a/b. This suggests that in the case of miR-21, finding a small set of targets mediating downstream effects might be more feasible compared to research on other miRNAs.

The current investigation demonstrates the feasibility of miRNA profiling using barcoded small-RNA sequencing of a multiplexed cDNA library. Our study, to our knowledge, is the first report of human kidney miRNA transcriptome small RNA sequencing. While more demanding in terms of laboratory procedures, sequencing provides information above and beyond other profiling platforms, and the barcode design keeps costs and labor competitive with other methods. We have validated, with a small but independent cohort, differential miRNA expression between IFTA biopsies and normal allograft biopsies and provide preliminary data of the association between miRNA expression levels and kidney allograft function and survival.

METHODS

Study Cohorts

We studied 26 kidney allograft biopsy samples from 26 kidney-transplant recipients who had undergone either a clinically-indicated kidney allograft biopsy or a surveillance (protocol) biopsy. Further details about the study cohort and RNA extraction are provided in the supplementary digital content (SDC) text. All patients provided written informed consent and the Institutional Review Board approved the study.

MiRNA Sequencing and Data Analyses

We used 0.5 μg of total RNA from each sample for library preparation as previously described (20, 37). Heatmaps (‘pheatmap’) and multidimensional-scaling plot (‘scatterplot3d’) were generated using R/Bioconductor. We tested for differentially expressed miRNA with DESeq (38) and used a published Argonaute PAR-CLIP dataset (24) to identify targets of differentially expressed miRNA (39). Additional details of miRNA sequencing, data analyses, quantification by RT-PCR assays and evaluation of the association between miRNA expression and allograft outcomes are provided in the SDC text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Rockefeller University’s Genomics Core Facility and Dr. Scott Dewell in particular, in sequencing of the small-RNA, and also acknowledge Dr. Moin A. Saleem (Bristol, UK) for providing HK2 cell pellets.

Funding Support:

IZB was supported by an award (UL1RR024143) from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research and was also supported in part by a fellowship from the American Physicians Fellowship for Medicine in Israel.

TM is supported by an award (K08-DK087824) from the NIH.

MS is supported in part by an award from the NIH (2R37-AI051652) and from the Qatar National Research Foundation (NPRP 08-503-3-11).

This work was supported in part by an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Center award (ULI RR 024996) to Weill Cornell Medical College.

Abbreviations

- 3′UTR

3′ untranslated region

- FDR

false detection rate

- GLM

general linear model

- IFTA

interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- MiRNA

microRNA

- PAR-CLIP

photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation

- RT-QPCR

reverse-transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SCr

serum creatinine

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

IZB: participated in designing the study, performing the research, analyzing the data, and writing the article. No conflict of interest.

TM: participated in designing the study, performing the research, analyzing the data, and writing the article. No conflict of interest.

PM: Contributed new reagents or analytic tools and participated in analyzing the data. No conflict of interest.

FBM: Participated in analyzing the data. No conflict of interest

TT: participated in designing the study, analyzing the data, and writing the article. No conflict of interest.

MS: participated in designing the study, analyzing the data, and writing the article. No conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) OPTN / SRTR 2010 Annual Data Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias M, Seron D, Moreso F, Bestard O, Praga M. Chronic renal allograft damage: existing challenges. Transplantation. 2011;91 (9 Suppl):S4. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821792fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nankivell BJ, Chapman JR. Chronic allograft nephropathy: current concepts and future directions. Transplantation. 2006;81 (5):643. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000190423.82154.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravin A, Tuschl T. Identification and characterization of small RNAs involved in RNA silencing. FEBS Lett. 2005;579 (26):5830. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farazi TA, Horlings HM, Ten Hoeve JJ, et al. MicroRNA sequence and expression analysis in breast tumors by deep sequencing. Cancer Res. 2011;71 (13):4443. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petillo D, Kort EJ, Anema J, Furge KA, Yang XJ, Teh BT. MicroRNA profiling of human kidney cancer subtypes. Int J Oncol. 2009;35 (1):109. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun H, Li QW, Lv XY, et al. MicroRNA-17 post-transcriptionally regulates polycystic kidney disease-2 gene and promotes cell proliferation. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37 (6):2951. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagalakshmi VK, Ren Q, Pugh MM, Valerius MT, McMahon AP, Yu J. Dicer regulates the development of nephrogenic and ureteric compartments in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int. 2011;79 (3):317. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung M, Schaefer A, Steiner I, et al. Robust microRNA stability in degraded RNA preparations from human tissue and cell samples. Clin Chem. 2010;56 (6):998. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.141580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Y, Sui W, Lan H, Yan Q, Huang H, Huang Y. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression patterns in renal biopsies of lupus nephritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29 (7):749. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saal S, Harvey SJ. MicroRNAs and the kidney: coming of age. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18 (4):317. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832c9da2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G, Kwan BC, Lai FM, et al. Intrarenal expression of miRNAs in patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23 (1):78. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang G, Kwan BC, Lai FM, et al. Intrarenal expression of microRNAs in patients with IgA nephropathy. Lab Invest. 2010;90 (1):98. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shan J, Feng L, Luo L, et al. MicroRNAs: potential biomarker in organ transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2011;24 (4):210. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anglicheau D, Sharma VK, Ding R, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles predictive of human renal allograft status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106 (13):5330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813121106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartono C, Muthukumar T, Suthanthiran M. Noninvasive diagnosis of acute rejection of renal allografts. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15 (1):35. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283342728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sui W, Dai Y, Huang Y, Lan H, Yan Q, Huang H. Microarray analysis of MicroRNA expression in acute rejection after renal transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2008;19 (1):81. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit KV, Milosevic J, Kaminski N. MicroRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res. 2011;157 (4):191. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anglicheau D, Muthukumar T, Hummel A, et al. Discovery and Validation of a Molecular Signature for the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Human Renal Allograft Fibrosis. Transplantation. 2012;93 (11):1136. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824ef181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafner M, Renwick N, Brown M, et al. RNA-ligase-dependent biases in miRNA representation in deep-sequenced small RNA cDNA libraries. RNA. 2011;17 (9):1697. doi: 10.1261/rna.2799511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blow MJ, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, et al. RNA editing of human microRNAs. Genome Biol. 2006;7 (4):R27. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawahara Y, Zinshteyn B, Sethupathy P, Iizasa H, Hatzigeorgiou AG, Nishikura K. Redirection of silencing targets by adenosine-to-inosine editing of miRNAs. Science. 2007;315 (5815):1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1138050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129 (7):1401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141 (1):129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neal CS, Michael MZ, Pimlott LK, Yong TY, Li JY, Gleadle JM. Circulating microRNA expression is reduced in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26 (11):3794. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scian MJ, Maluf DG, David KG, et al. MicroRNA profiles in allograft tissues and paired urines associate with chronic allograft dysfunction with IF/TA. Am J Transplant. 2011;11 (10):2110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarver AL. Toward understanding the informatics and statistical aspects of micro-RNA profiling. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3 (3):204. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alon S, Vigneault F, Eminaga S, et al. Barcoding bias in high-throughput multiplex sequencing of miRNA. Genome Res. 2011;21 (9):1506. doi: 10.1101/gr.121715.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li JH, Zhu HJ, Huang XR, Lai KN, Johnson RJ, Lan HY. Smad7 inhibits fibrotic effect of TGF-Beta on renal tubular epithelial cells by blocking Smad2 activation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13 (6):1464. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000014252.37680.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong X, Chung AC, Chen HY, Meng XM, Lan HY. Smad3-mediated upregulation of miR-21 promotes renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22 (9):1668. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jazbutyte V, Thum T. MicroRNA-21: from cancer to cardiovascular disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11 (8):926. doi: 10.2174/138945010791591403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farazi TA, Spitzer JI, Morozov P, Tuschl T. miRNAs in human cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223 (2):102. doi: 10.1002/path.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy S, Khanna S, Hussain SR, et al. MicroRNA expression in response to murine myocardial infarction: miR-21 regulates fibroblast metalloprotease-2 via phosphatase and tensin homologue. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82 (1):21. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456 (7224):980. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yi-Chun J, Nair V, Ju W, Luo J, Orkin S, Nelson RG. American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week. Vol. 22. Philadelphia, PA: Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, supplement; 2011. MicroRNA-21 and TGF-beta in diabetic glomerulopathy. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu SD, Lin FM, Wu WY, et al. miRTarBase: a database curates experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39 (Database issue):D163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berninger P, Gaidatzis D, van Nimwegen E, Zavolan M. Computational analysis of small RNA cloning data. Methods. 2008;44 (1):13. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11 (10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA. org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36 (Database issue):D149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.