Abstract

Background

Previous studies demonstrate that anxiety is characterized by biased attention toward threats, typically measured by differences in motor reaction time to threat and neutral cues. Using eye-tracking methodology, the current study measured attention biases in anxious and nonanxious youth, using unrestricted free viewing of angry, happy, and neutral faces.

Methods

Eighteen anxious and 15 nonanxious youth (8–17 years old) passively viewed angry-neutral and happy-neutral face pairs for 10 s while their eye movements were recorded.

Results

Anxious youth displayed a greater attention bias toward angry faces than nonanxious youth, and this bias occurred in the earliest phases of stimulus presentation. Specifically, anxious youth were more likely to direct their first fixation to angry faces, and they made faster fixations to angry than neutral faces.

Conclusions

Consistent with findings from earlier, reaction-time studies, the current study shows that anxious youth, like anxious adults, exhibit biased orienting to threat-related stimuli. This study adds to the existing literature by documenting that threat biases in eye-tracking patterns are manifest at initial attention orienting.

Keywords: anxiety, threat-bias, orienting, eye tracking

INTRODUCTION

Mounting evidence links attention biases and anxiety disorders.[1–3] Enhanced attentional vigilance to threat can lead to hyperarousal, difficulty disengaging from minor threats, and avoidance. Threat-related attention biases are particularly pertinent for the developmental trajectory of anxiety in children and adolescents. Because children undergo sensitive periods of circuit formation, and attention may modulate the impact that stimuli exert on the maturing circuits, understanding the extent to which threat-related attention is biased in developmental anxiety disorders is of paramount importance to the neuronal structure that underlies anxiety. Furthermore, childhood and adolescence are often one of the earliest times during which threat-related stimuli are encountered, and as such, learning can shape emerging anxious phenotypes by establishing and reinforcing emotional “habits.” Given the importance of such cognitive processes on budding circuit and emotional organization, attention biases to threat may exert a particularly strong effect on youth.[4] The current study was designed to further examine attention biases in anxious youth using a paradigm that is particularly well suited for developmental studies.

Several well-established experimental paradigms have been used to compare attention biases in anxious and healthy populations.[3] Across these paradigms, adults with anxiety disorders show a biased tendency to orient toward threats.[1] However, findings in anxious children are equivocal.[5,6] These inconsistencies may be related to several factors. First, control of attention is dependent upon the maturation of fronto-cortical circuits, which are not fully developed until late adolescence,[7] thereby increasing intrasubject variability. Second, threat intensity has been shown to influence direction of attention bias and threat intensity may vary from adults to children even with comparable stimuli. Finally, many threat bias studies use motor-response times as a measure of attention bias and such cross modality integration may also vary across development. Consequently, patterns of attention biases in anxious youth may be affected by a number of different factors generating patterns that are less clear than in adults.

The dot-probe task is one such motor-dependent task commonly used to measure attention biases. In this task, two different facial expressions, typically one angry and the other neutral, appear simultaneously, followed by a visual probe, which replaces one of the faces and prompts a motor response. Threat-related attention bias is inferred from reaction-time differences between trials in which the probe replaces the angry face relative to trials in which the probe replaces the neutral face.[8] On the dot-probe task, anxious adults generally show a greater threat attention bias, manifesting as faster reaction time toward threat-related stimuli.[1,2] This effect has been consistently observed across studies, however, the magnitude is not large[1] and results can vary as a function of key experimental methods.[6]

Though the dot-probe task has generated a relatively consistent profile in studies of adult anxiety, findings from the dot-probe task in anxious youth are less consistent. Some studies find an orienting bias toward threat, whereas others find a bias away from threat; still others find that both anxious and nonanxious youth exhibit a threat bias relative to adults (for a comprehensive review see.[5,6]) As an attention-bias paradigm the dot probe has many shortcomings, particularly for developmental studies. First, developmental dot-probe studies may be influenced by factors other than attention, as detailed above. A second problem with the dot-probe paradigm is that stimulus duration can be another key methodological factor that appears to account for inconsistent findings. Dot-probe studies that use threatening stimuli presented for 500 ms (a standard approach) generally identify a threat bias in anxious but not healthy individuals.[1,9] However, dot-probe studies using stimuli presented for longer time often fail to detect such between-group differences. Such time-dependent discrepancies have generated complex models of the anxiety–attention relationship,[3] which generally suggest that anxiety is characterized by an initial, very rapid engagement of attention by threat, followed by more complex evaluative and avoidant cognitive processes that unfold over time. The temporal dynamics of attention engagement and avoidance may differ across anxiety states and development.[10, 11] Because attention is measured at only one time point in dot-probe tasks (during motor-response elicitation), which occurs after stimulus presentation, differences in stimulus duration can generate complex results. Furthermore because attention may unfold in a complex manner across time, the dot-probe task is limited by an inability to distinguish biases in the initial orienting toward threat from the subsequent disengagement from threat. Results using various manipulations suggest that both processes contribute to attention bias in anxiety disorders.[12–15]

The paradigm employed in the current study adopts a stimulus structure similar to a dot-probe task, but rather than using button-press speed to index attention, visual fixation patterns across relatively long stimulus exposure periods were assessed. This approach minimizes many limitations intrinsic to the traditional dot-probe task and quantifies attention across time. In the present study, we recorded eye movements while participants viewed pairs of faces (angry-neutral, happy-neutral, neutral-neutral) across a prolonged 10-s period of exposure.

Several studies have used eye-tracking methods to assess attentional biases to emotional stimuli in anxious adults. Most of these provide support for biased attention orienting toward threat among patients with various forms of anxiety, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),[12] generalized anxiety disorder (GAD),[16] and high trait anxiety.[17, 18] To date, only two studies have used eye tracking to study the time course of attention biases in anxious youth, both used the passive-viewing approach employed in the current study. In both studies, key differences in attention engagement to emotional stimuli were evident at the onset of stimulus exposure but not later in the trial. In one study, findings varied by age and anxiety status. Here, anxious children directed attention away from positive emotional faces in the first 500 ms of stimulus viewing, whereas anxious adolescents directed attention away from negative emotional faces, with both anxious groups differing from age-matched healthy comparison group.[19] In the second study, relative to healthy children, children with separation anxiety disorder (SAD) exhibited more fixations toward negative emotional scenes, but only during initial stimulus presentation.[20]

Based on prior behavioral and eye-tracking studies in anxious adults and youth, we hypothesized that anxious youth would show threat-related bias in visual fixation patterns in the initial, earliest temporal phases of stimulus exposure. Specifically, anxious youth were expected to orient their first fixation to threat-related stimuli more frequently and more quickly than healthy youth. In order to explore potential systematic changes in eye-movement patterns during relatively long stimulus presentation, we utilized long-duration stimuli, and performed analyses on attention biases across to both angry and happy faces across a prolonged exposure time. Because results from prior studies only generate clear, a priori hypotheses regarding orienting to threat faces in the earliest phases of stimulus exposure, no a priori predictions were made for fixation patterns to threat faces during longer exposure intervals, nor to happy faces across any time interval. Therefore, although we conducted these analyses here for the sake of completeness, results from these later analyses are to be considered exploratory.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Eighteen anxious and 15 nonanxious youth (8–17 years old) participated in this study. Anxious youth were identified when they sought treatment for an impairing anxiety disorder; all met DSM-IV criteria for a current anxiety diagnosis of GAD, SAD, or social phobia (SoPh). Youth with comorbid major depression (MDD), severe trauma, and those taking psychotropic medication were excluded. Diagnoses were determined with the Kiddie Schedule for AffectiveDisorders—Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) administered by a clinician. All clinicians were trained to an adequate level of reliability (κ > 0.70) for all disorders, and diagnoses were confirmed by a clinical interview with a senior psychiatrist. Inclusion criteria for healthy comparison subjects consisted of an absence of medical or psychiatric problems as determined by K-SADS. As depicted in Table 1, the groups did not differ on any of the demographic variables measured. Participants were recruited through local newspaper advertisements and word of mouth. Before participation, informed consent was obtained from parents of all participants and informed assent was provided by participants. All procedures were approved by the NIMH Institutional Review Board.

TABLE 1.

Sample demographics

| Anxious group N or mean (SD) |

Control group N or mean (SD) |

Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 9 | 5 | ||

| Female | 9 | 10 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 15 | 13 | ||

| African American | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 | ||

| Age | 12.25 (3.27) | 14.31 (2.23) | t(31) = −2.06 n.s. |

INSTRUMENTS AND METHOD

Visual Task

Fifty face pairs were presented randomly to each participant. The faces were derived from a standardized face emotion set of adult actors (Tottenham and Nelson, http://www.macbrain.org/faces/index.htm). All nonfacial features were removed from the images and gray-scale faces were displayed on a black background. Each face pair consisted of two pictures of the same individual with different facial expressions (20 angry-neutral, 20 happy-neutral, and 10 neutral-neutral). Equal numbers of male and female stimuli were used. The side depicting the emotional expression was counterbalanced across the stimulus set. Stimuli were displayed in full screen on a 16″ computer monitor approximately 60 cm in front of subject. Each face occupied approximately 2° on either side of visual field.

Apparatus

Eye movements were recorded from the left pupil using a remote mounted eye tracker with a sampling rate of 240 Hz (Applied Science Laboratories; ASL Inc., Bedford, MA). The study was conducted in an illuminated room with standard fluorescent lights. Participants were comfortably seated in a chair in front of the computer. A chin rest was used to minimize movement and to ensure an invariable distance of 60 cm from the monitor. A standard calibration procedure took place at the beginning of each experiment, during which the position of the eye was recorded in nine target locations on the screen. Participants were instructed to simply look at the faces on the screen. The visual task therefore required only passive viewing, with no additional behavioral demands.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

ASL software was used to calculate the location, onset, and duration of fixations (Applied Science Laboratories). A fixation was defined as a stable gaze within 1° of visual angle lasting at least 100 ms. Three primary analyses of fixation patterns were performed. The first two analyses focused on initial vigilance to threat, and a third assessed attention over time.

Prior research has consistently found anxiety-related bias for angry faces, but results from studies of bias to happy faces have been inconsistent, particularly among children and adolescents. As a result, most prior studies on anxiety-related attention bias include both happy faces and angry faces as part of the study design. However, the statistical approach in the vast majority of past studies on attention bias in pediatric anxiety conducts separate analyses on happy-bias and threat-bias scores.[11, 21–23] Therefore, a similar approach is followed in the current study. Note that this approach does not provide definitive conclusions on the stimulus specificity of attention biases. Consequently, secondary analyses used a multivariate, repeated-measure approach to evaluate evidence on emotion specificity of any observed attention biases.

Analysis 1 (Vigilance Bias): Probabilities of First Fixation Direction

To index initial orienting response, we assessed the proportion of trials in which the first fixation was to the side of the screen where the emotional stimulus was presented, an important variable in prior eye-movement studies.[12, 18,19] Prior behavioral research allows for the generation of relatively clear a priori hypotheses for this first analysis for the angry-neutral stimuli. Anxious adults and youth show a temporally early hypervigilance to threat-related stimuli. As such we predicted an initial bias toward angry faces in angry-neutral trials.[12, 16,19] Probabilities of first fixation to either the angry or neutral stimulus were averaged across the 20 trials. A t-test was used to compare groups on probability of fixation toward threat.

Analysis 2 (Vigilance Bias): Latency of First Fixation

This variable was quantified as the time from stimuli onset until the first fixation to either the emotion or neutral face. Much like biases in the probability of first fixations, prior research also generates clear predictions concerning biases in latency of this initial fixation for angry relative to neutral faces.[16,18] Therefore, much like the probability analysis, analyses of latency focused specifically on between-group differences for first fixation on angry compared to neutral faces in trials where angry-neutral pairs appeared. A repeated-measure ANOVA of latency data, with stimulus type (angry, neutral) × group (anxious, nonanxious youth) was used. Note that this measure is not completely independent from the first vigilance metric as the first fixation will always be a shorter latency than subsequent ones. Importantly, however, these measures do not completely overlap. In order to decouple these two measures, a secondary analysis was conducted only in trails in which first fixation was directed toward the angry face.

Analysis 3 (Maintenance Bias): Dwell Time on Each Stimulus

Finally, in order to assess biases across longer periods of threat exposure, we measured the total amount of time each subject fixated on each stimulus across the entire trial. Unlike data on the direction and latency for the first fixation, consistent findings do not emerge in the literature with respect to analyses of eye-movement patterns during longer duration stimulus exposures. Thus, this final set of analyses used an exploratory approach, rather than focused testing of specific hypotheses. For the overall gaze duration, we divided each of the 10-s trials into 20 time bins of 500 ms in order to decompose the temporal dynamics of attention allocation across the prolonged stimulus duration.[13,24] We used 500 ms as the time unit, based on previous studies using this stimulus duration.[20] The mean duration of fixations to angry and neutral stimuli were analyzed in a three-way repeated-measure ANOVA with Time (20 time bins) × stimulus type (angry, neutral) × group (anxious, nonanxious youth). Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used to correct for sphericity. A separate analysis using the same methods was conducted for the happy-neutral trials.

RESULTS

PROBABILITIES OF FIRST FIXATION DIRECTION

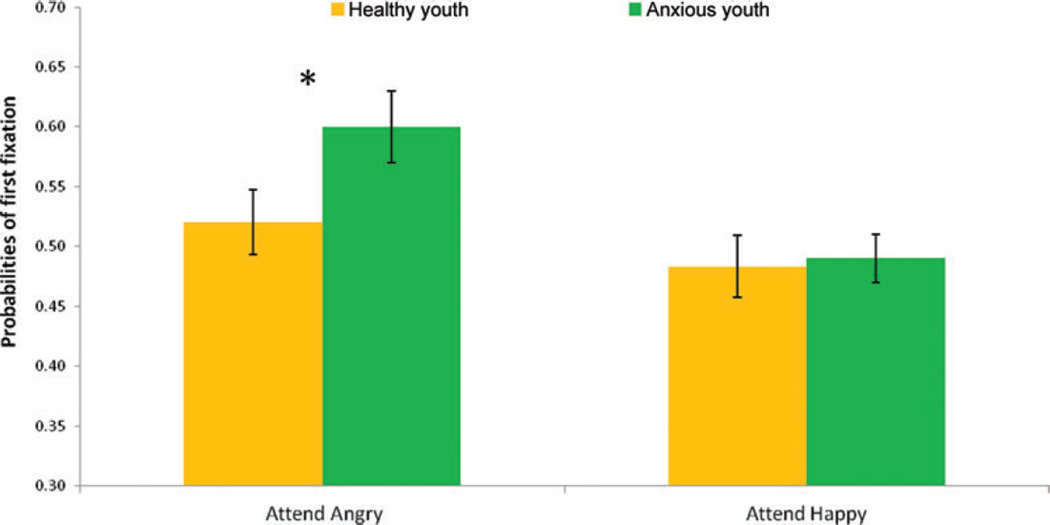

Analysis of the angry-neutral pairs revealed that anxious youth were more likely to direct their first fixation to the angry stimulus (M = 0.61, SD = 0.11) than nonanxious youth (M = 0.52, SD = 0.10), t(30) = 2.35, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.86. The proportion of first fixating on the angry side was significantly greater than chance (50%) in the anxious t(16) = 4.16, P < .01, Cohen’s d = 1.00, but not in the nonanxious, group, t(14) = 0.74, P > .05, Cohen’s d = 0.20. Therefore, anxious but not healthy youth show a threat-bias in initial orienting.

For the happy-neutral face pairs, neither the anxious nor healthy group demonstrated bias (Ps > .05), with no between-group differences (Ps > .05). Probabilities of fist fixation direction are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proportions of first fixation to angry and happy stimuli in emotional-neutral pairs among anxious and nonanxious youth.

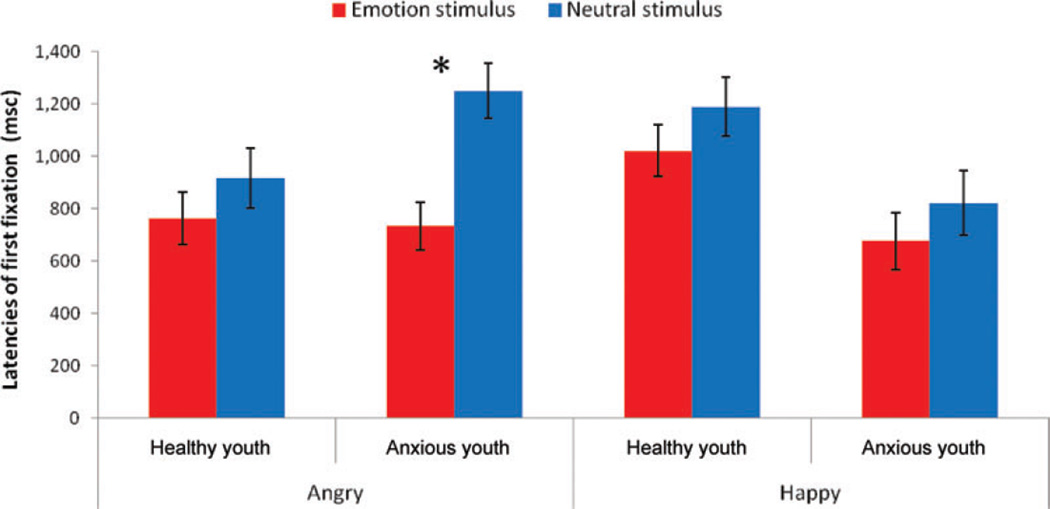

LATENCY OF FIRST FIXATION

A repeated-measure ANOVA on the angry-neutral pairs with stimulus type (angry, neutral) × group (anxious, nonanxious youth) yielded a significant interaction, F(1, 29) = 4.33, P < .05, partial η2 = .13. The first fixation to angry (M = 0.734, SD = 0.344) was faster than to neutral (M = 1.250, SD = 0.495) in anxious youth, t(16) = −4.91 P < .01, but not among nonanxious youth (M = 0.764, SD = 0.408) (M = 0.917, SD = 0.336), t(13) = −1.06 P > .05. Latency to attend to emotion only on trials in which the first fixation was directed toward the angry face were not different between the anxious group (M = 0.37 SD = 0.135) and the nonanxious group (M = 0.42, SD = 0.183), t(31) = 0.95, P > .05, Cohen’s d = 0.31, indicating that the latency and probability of initial fixation measures were likely a reflection of the same hypervigilance phenomenon.

The analysis of the happy-neutral pairs revealed a significant main effect for stimulus type, F(1, 29) = 11.78, P < .01, partial η2 = .29. Across both groups, the first fixation was faster to the happy (M = 0.865, SD = 0.436) than the neutral stimulus (M = 1.023, SD = 0.489). In addition, a main effect was found for group, F(1, 29) = 5.64, P < .05, partial η2 = .16, indicating that anxious youth exhibited a faster first latency than nonanxious youth to happy-neutral pairs (collapsed across happy-neutral stimulus type). No group × stimulus type interaction was detected (P > .05). The latency results are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Latencies of first fixation to angry-neutral pairs and happy-neutral pairs among anxious and nonanxious youth.

DWELL TIME

A repeated-measure ANOVA on the angry-neutral pairs with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction, with time (20 time bins) × stimulus type (angry, neutral) × group (anxious, nonanxious youth) was not significant, F(7.40, 229.16) = 1.608, P > .05, partial η2 = .05. Only the main effect of time was statistically significant, F(8.74, 270.96) = 7.33, P < .01, partial η2 = .19.

The same analysis was conducted for the happy-neutral pairs. The three-way interaction of time (20 time bins) × stimulus type (happy, neutral) × group (anxious, nonanxious youth) was not significant, F(8.90, 275.94) = 1.499, P > .05, partial η2 = .05. Only the main effect of time was significant, F(8.74, 270.96) = 7.33, P < .01, partial η2 = .19.

EMOTION SPECIFICITY

In addition to performing independent analyses on each emotion-neutral pair separately, we also performed a full omnibus repeated-measures ANOVA with emotion (angry, happy faces) × group (anxious, nonanxious) on each measure. Using this approach, group by emotion interactions were not significant for initial fixation probability (F(1, 30) = 2.75, P > .05, partial η2 = .08, power = 0.361), and yielded only a trend for latency, F(1, 29) = 3.31, P = .079, partial η2 = .10, power = 0.421.

DISCUSSION

To further assess the hypothesis that one of the key attributes of anxiety is threat hypervigilance, we examined differences between anxious and nonanxious youth in eye-fixation patterns made in the context of viewing threat and neutral face pairs. Our results indicate that, under free viewing conditions, anxious relative to nonanxious youth had a greater tendency to direct initial attention toward angry than neutral faces. They also displayed a shorter latency to fixate on angry relative to neutral faces than their nonanxious counterparts. It is important to note, however, that the latency and direction of the first fixation are not entirely independent: a bias in initial fixation could also influence latency. Regardless, both measures do reflect the importance of the early response to threatening stimuli in differentiating healthy from anxious youth.

The importance of alterations in the earliest phases of attentional engagement to threat-related stimuli for childhood anxiety disorders replicates findings in Gamble & Rapee[19] and In-Albon.[20] That is, both prior studies found that anxious and nonanxious youth differed primarily in fixation patterns early, but not late, in stimulus presentation. Nevertheless, other findings across the current and prior reports show some differences. Although In-Albon et al. reported a bias toward threatening pictures in anxious children, Gamble and Rapee reported an attention bias away from aversive stimuli in anxious adolescents. Although differing from the pattern of threat reported by Gamble and Rapee, our results are consistent with a majority of behavioral studies in adults that have demonstrated attention bias toward threat. Thus, the current results are largely consistent with findings indicating that anxiety involves enhanced responding toward threat during early phases of attention allocation. However, anxiety-related biases away from threatening stimuli have been reported by us and others.[6,22] Thus, although biases have been found consistently in early phases of attention orienting tasks, the direction of bias is often hard to predict. As mentioned in the introduction, direction of attention bias may be affected by methodological issues, subject developmental state, severity of disorder, intensity of stimulus, and possibly other factors.

A further analysis of the latency of first fixation to the threat among anxious youth reveals that this difference derives primarily from a slower latency to the neutral stimuli. In attentional tasks such as the dot probe, where two competing stimuli are presented simultaneously, attention patterns are most accurately evaluated by relative differences in the subject’s response to each of the two stimuli (emotion-neutral). For example, attention biases are most commonly operationalized by the relative difference in reaction time to two types of stimuli. The current eye-tracking study uses a similar task where two competing stimuli are presented together. With this approach, between-group differences in attention are inferred from relative differences in within-trial orienting to each type of stimulus presented in a pair, as reflected in the latency of first fixation and overall viewing time to each type of stimulus. Although this approach of paired-stimulus presentation replicates the approach used in prior, reaction-time studies, it does have limitations. Most importantly, it precludes isolation of attentional biases to one specific type of stimulus (i.e., emotional) without considering the relative influence of the concurrently presented type of stimulus (i.e., neutral). Thus, it is most appropriate to use relative differences to quantify a bias.

In addition, no between-group differences were found in the analysis that included only trials in which the first fixation was toward the angry face, indicating that although anxious youth tended to initially orient toward the threatening face more than the nonanxious youth, the speed with which they made this initial fixation did not differ between the groups when only initial angry fixations were included. A secondary analysis (not presented here) revealed that most participants, irrespective of their diagnostic status, tended to shift their attention from the face associated with their first fixation to the other face in the pair, during their second fixation (~70% of trials). Hence, analyzing the mean latencies to first fixation for each face across all trials could partially reflect both the time for the initial orientation and the stimulus ability to capture attention, both indicating vigilance.

Other methodological constraints of eye-fixation analyses make the interpretation of the attentional bias difficult. For example, fixation in the current study was defined as a stable gaze within 1° of visual angle lasting at least 100 ms, the definition most frequently used in prior studies. However, future eye-movement studies might consider alternative approaches. This is because prior to the first fixation, subjects often exhibit rapid, brief duration eye movements between the two stimuli. Consequently, the slower first fixation to the neutral compared to the angry face among anxious youth could derive from longer prefixation scanning patterns (more saccades) of the two stimuli, context effects, by which the angry and neutral stimuli compete to draw attention, or potentially more difficulty in disengaging from the angry face if that was the first fixation. Such possibilities should be considered in future research, since the current paradigm was designed to identify group differences in eye-movement patterns examined in previous studies, as reflected in the direction and latency of initial, persistent fixations between two competing stimuli.

Posner and Petersen[25] divide the attention system into three subsystems, which operate on different time scales, require different levels of cognitive control, and perform different but interrelated functions. According to this model, the initial orienting phase happens very rapidly, is comprised both voluntary and involuntary control processes, and can even be engaged without foveal fixation of the stimulus. In contrast, the latter two processes of selecting and maintaining attention occur later in the engagement process and involve predominately voluntary control.[25] The results of the current study, like those of many other tasks,[3] indicate that the most prominent difference in attention allocation between anxious and nonanxious individuals occurs in early orienting, and not in the later stages of attention. Anxious youth were more likely to orient their first fixation to the angry faces, and they were faster to do so than nonanxious counterparts. This implies that in a potentially threatening context, the first and, possibly, involuntary attention phase is atypical in anxious youth.

In contrast to the orienting phase, the current data did not provide support for vigilance avoidance theories, which posit that an initial hypervigilance response is followed by an avoidance response with continued exposure to threat stimuli.[10, 11] Although anxious youth exhibited vigilance toward threats during the early portion of the trial, they did not show systematic avoidance, compared to their nonanxious counterparts, in the later part of the trial. However, if individuals employed different temporal dynamics in their engagement of vigilance-avoidance strategies, a pattern of avoidance on the individual level may have been obscured by our group level analysis.

Although the data demonstrate a clear pattern of vigilance for angry faces in anxious youth, the results of the happy bias are less clear. The anxious group did not demonstrate an increased probability of initial fixation to happy faces. Further, emotionality of stimulus (either happy or angry) did not affect initial fixation of the nonanxious group. These results are consistent with previous studies indicating that typically developing children show no attentional biases to threat[1] or happy stimuli,[6] and with previous eye-tracking studies that failed to find group differences in fixation patterns to happy faces among anxious and nonanxious adolescents.[19] Moreover, omnibus statistical models including both happy and angry faces generally failed to find interactions between the valence of face emotions and anxiety-disorder status. Nevertheless, statistical power is limited on such higher order interactions, and minimal evidence emerged for any consistent biases to happy faces in this and other studies. As a result, the failure to detect group-by-emotion interactions may reflect a Type II error.

Analysis of happy-neutral pairs in the current study did reveal that all participants had faster latencies for the happy face compared to the neutral one, indicating some degree of attention bias to happy across both groups. Although outwardly similar across groups, this same attention pattern could reflect the influence of distinct psychological processes in the two subject groups. That is, the nonanxious group may shift attention to the smiling face as a sign of attention to positive social reinforcement, whereas the anxious group might shift attention based on perceptions of social threat.[26] The current paradigm is ill suited for evaluating these possibilities.

There was, however, one between-group difference in fixation patterns on happy-neutral trials: the anxious group, compared to the nonanxious group, demonstrated an overall faster initial fixation on happy-neutral trials, although the direction of this initial fixation (toward happy or neutral) did not differ. This may suggest some nonspecific arousal effect in anxious subjects in the context of positive emotion. However, when using behavioral measurements such as the dot-probe task, most of the published studies have not found either a bias toward positive stimuli or similar nonspecific arousal effects. Based on the dearth of previous data, the relatively small sample, and the fact that the nonsignificant differences between groups that could reflect Type II errors, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions from this finding without independent replication (for a complete review see[6]).

From a clinical perspective, the present data may have relevance for attention training treatment regimens. Attention training is an implicit learning process in which patients are exposed continually to experiences that progressively shape their attentional focus toward or away from different stimulus classes. For example, the use of the dot-probe task in attention retraining involves consistently placing the probe in locations that are spatially incongruent with the threat stimulus. Subjects thereby learn to direct their attention away from the threat in order to complete the task quickly and accurately.[27] Recent data indicate that biased orienting toward threats and rewards may be modified through training, and these training regimens may have a clinical effect. Such training protocols may be especially important in youth, for whom medication is not always an option and for those who respond poorly or discontinue interventions based on aversive exposure therapy.

A recent meta-analysis reports a moderate clinical effect size for attention retraining methods.[28] This suggests that teaching anxious individuals to orient attention away from threat not only alters attention bias within the task, but also reduces anxious symptoms outside the confines of the task. A major scientific effort is underway to identify methods of attention training that could eventually maximize these clinical effects in anxious youth. Results from the current study suggest that attention training might be most effective when targeted at the earliest stages of stimulus presentation. Consequently, this type of learning could modify the rapid (voluntary and involuntary) processes involved in the allocation of attention, similar to the automatic learning that occurs with motor-learning routines. Most attention training procedures have used the dot-probe task to measure, and then manipulate attention. If eye movements are indeed a direct measure of attention orienting, it is reasonable to assume that attention training could also be delivered by manipulating and training saccades. This may be both a more direct and more effective means of attention control. This idea should be examined in future research.

Finally, the results of this study should be considered in light of some methodological limitations. First, the age range of participants in both the anxious and nonanxious groups was large, and the numbers of participants did not allow for a more specific analysis differentiating children from adolescents. Based on previous studies,[19] attention biases of children and adolescents do not necessarily show the same pattern and therefore treating them as a homogeneous group may obscure other plausible effects. Along the same lines, the restricted sample size did not allow for the analysis of specific diagnostic subgroups among the anxious youth. Both the small size and heterogeneous nature of our sample minimize statistical power on tests of between-group differences. As a result, our failure to detect hypothesized associations could reflect Type II errors. However, it is important to note that our study did detect some potentially important associations, which manifested with large effects. Hence, because our study did detect these associations despite the limitations in power associated with small, heterogeneous samples, our findings suggest that a relatively strong association exists between eye-movement response and clinical anxiety. Previous research demonstrated larger effect sizes of attention bias to threats when the sample was more heterogeneous and disorder-specific stimuli were used.[27] Selecting the right combination of stimuli for specific patient populations in future research, and using larger samples of clinically relevant subgroups, could impact the magnitude of attention biases. Another limitation might result from using adult faces as emotional stimuli when studying group difference between anxious and nonanxious youth. One previous study showed that children are slower in responding to adult, compared to child, emotional stimuli.[29] It might be the case that the emotion presented by the adult faces, compared to neutral faces, are particularly salient cues for children, irrespective of anxiety diagnoses. Future studies could examine this by using age-appropriate emotional stimuli that have recently become available.[30] Finally, although analyzing the two types of emotions separately coincide with our a-priori hypothesis and previous results, it is important to note that this analytic approach could not indicate emotion specificity and it is more prone to Type I error.

In sum, consistent with earlier behavioral as well as some eye-tracking findings, the current study shows that anxious youth, like anxious adults, exhibit a bias in initial orienting to threat-related stimuli. This bias is evident in initial, but not later, attention process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH.

Contract grant sponsor: NIMH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. No conflict of interest was declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, et al. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(1):1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(9):809–848. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cisler JM, Koster EH. Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: an integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pine DS, Helfinstein SM, Bar-Haim Y, et al. Challenges in developing novel treatments for childhood disorders: lessons from research on anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(1):213–228. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puliafico A, Kendall P. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious youth: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2006;9(3):162–180. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shechner T, Britton JC, Perez-Edgar K, et al. Attention biases, anxiety, and development: toward or away from threats or rewards? Depress Anxiety. 2011 doi: 10.1002/da.20914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hare TA, Tottenham N, Davidson MC, et al. Contributions of amygdala and striatal activity in emotion regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLeod C, Mathews A, Tata P. Attentional bias in emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(1):15–20. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frewen PA, Dozois DJ, Joanisse MF, Neufeld RW. Selective attention to threat versus reward: meta-analysis and neural-network modeling of the dot-probe task. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(2):307–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogg K, Bradley BP, de Bono J, Painter M. Time course of attentional bias for threat information in non-clinical anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(4):297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waters AM, Kokkoris LL, Mogg K, et al. The time course of attentional bias for emotional faces in anxious children. Cogn Emot. 2010;24(7):1173–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong T, Olatunji BO, Sarawgi S, Simmons C. Orienting and maintenance of gaze in contamination fear: biases for disgust and fear cues. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(5):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckner JD, Maner JK, Schmidt NB. Difficulty disengaging attention from social threat in social anxiety. Cogn Ther Res. 2010;34(1):99–105. doi: 10.1007/s10608-008-9205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koster E, Crombez G, Van Damme S, et al. Signals for threat modulate attentional capture and holding: fear-conditioning and extinction during the exogenous cueing task. Cogn Emot. 2005;19(5):771–780. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Damme S, Crombez G, Notebaert L. Attentional bias to threat: a perceptual accuracy approach. Emotion. 2008;8(6):820–827. doi: 10.1037/a0014149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogg K, Millar N, Bradley BP. Biases in eye movements to threatening facial expressions in generalized anxiety disorder and depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(4):695–704. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvo MG, Avero P. Time course of attentional bias to emotional scenes in anxiety: gaze direction and duration. Cogn Emot. 2003;19(3):433–451. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garner M, Mogg K, Bradley BP. Orienting and maintenance of gaze to facial expressions in social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(4):760–770. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamble AL, Rapee RM. The time-course of attentional bias in anxious children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(7):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.In-Albon T, Kossowsky J, Schneider S. Vigilance and avoidance of threat in the eye movements of children with separation anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(2):225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, et al. Attention bias toward threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(10):1189–1196. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825ace. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1091–1097. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attention bias for angry faces in children with social phobia. J Exp Psychopathol. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schofield CA, Johnson AL, Inhoff AW, Coles ME. Social anxiety and difficulty disengaging threat: evidence from eye-tracking. Cogn Emot. 2012;26(2):300–311. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.602050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashdan TB, Weeks JW, Savostyanova AA. Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: a self-regulatory framework and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(5):786–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bar-Haim Y. Research review: attention bias modification (ABM): a novel treatment for anxiety disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(8):859–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, et al. Attention bias modification treatment: a meta-analysis toward the establishment of novel treatment for anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(11):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benoit KE, McNally RJ, Rapee RM, et al. Processing of emotional faces in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Behav Change. 2007;24(4):183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger HL, Pine DS, Nelson E, et al. The NIMH Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS): a new set of children’s facial emotion stimuli. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(3):145–156. doi: 10.1002/mpr.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]