Abstract

Docosahexaenoylethanolamide, the structural analog of the endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand anandamide, is synthesized from docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in the brain. Although docosahexaenoylethanolamide binds weakly to cannabinoid receptors, it stimulates neurite growth, synaptogenesis and glutamatergic synaptic activity in developing hippocampal neurons at concentrations of 10–100 nM. We have previously proposed the term synaptamide for docosahexaenoylethanolamide to emphasize its potent synaptogenic activity and structural similarity to anandamide. Synaptamide is subjected to hydrolysis by fatty acid amide hydrolase, and can be oxygenated to bioactive metabolites. The brain synaptamide content is dependent on the dietary DHA intake, suggesting an endogenous mechanism whereby diets containing adequate amounts of omega-3 fatty acids improve synaptogenesis in addition to well-recognized anti-inflammatory effects.

Keywords: Synaptamide, Synaptogenesis, Neuritogenesis, N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine, Docosahexaenoic acid, Omega-3 fatty acid, Fatty acid amide hydrolase, Endocannabinoids, Anandamide

1. Introduction

In 1984 Howlett and Fleming observed that cannabinoids inhibit adenylate cyclase in a plasma membrane fraction obtained from neuroblastoma cells, and they suggested that cannabimimetic drugs function through a selective receptor-mediated process [1]. A specific, high-affinity binding site for cannabinoids was subsequently detected in rat brain by Devane et al. [2], and the receptor, designated as CB1, was cloned by Matsuda et al. [3]. Based on these findings, Mechoulam predicted that an endogenous ligand for the cannabinoid receptor might be present in brain, and because plant cannabinoids are lipid-soluble, that the endogenous ligand was a lipid-soluble compound [4]. This hypothesis proved to be correct, and Devane et al. isolated the endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand arachidonoyl ethanolamide, which they named anandamide, by extraction from porcine brain with organic solvents and lipid chromatography [5]. Two n-6 poly-unsaturated fatty acid ethanolamide analogs of anandamide, eicosatrienoyl ethanolamide and docosatetraenoyl ethanolamide, subsequently were isolated from porcine brain and found to bind to the cannabinoid receptor [6]. Because neural tissue is rich in n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), Hanus et al. suggested that acyl ethanolamides containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids also might be present in the brain, but this possibility was not investigated [6].

Subsequent studies demonstrated that DHA is converted to an ethanolamide derivative, N-docosahexaenolyethanolamine. This DHA-derived structural analog of anandamide has a number of bioactive functions such as neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis [7]. Because DHA ethanolamide promotes synaptogenesis and synaptic activity at physiologically relevant concentrations [7], we have proposed use of the term synaptamide to indicate its synaptogenic properties and chemical nature [8]. Despite the structural similarity, these bioactivities of synaptamide are mediated in an endocannabinoid-independent manner. To make a distinct contrast to anandamide, the term synaptamide is adopted for this review. Fig. 1 summarizes the similarities and differences in metabolism and function of synaptamide and anandamide.

Fig. 1.

Metabolism and function of synaptamide and anandamide. It is likely that synaptamide and anandamide share common pathways, although biosynthetic mechanisms for synaptamide production have not been characterized. Both are subjected to FAAH-mediated hydrolysis. While it is well-established that anandamide effects are mediated through CB1 and CB2 receptors, synaptamide functions in a cannabiniod-independent manner, promoting neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis. Further conversion to oxygenated metabolites is possible for anandamide and synaptamide.

2. Cannabinoid receptor binding

The first experimental results with synaptamide are contained in a 1993 study of anandamide binding to the human brain cannabinoid receptor [9]. The receptor was expressed in L-cells, and binding was tested by displacement of a radiolabeled cannabinoid receptor agonist bound to a membrane fraction isolated from the cells. As a part of the study, the selectivity of the receptor for anandamide relative to other chemically synthesized acylethanolamides was compared in a displacement assay. The Ki for eicosatrienoylethanolamide and docosatetraenoylethanolamide binding was only slightly higher than the Ki for anandamide binding, 543±83 nM. However, the Ki for synaptamide binding was 25-times greater, 12.2±0.5 μM, indicating much weaker binding compared to anandamide or the other ethanolamide derivatives containing 20- and 22-carbon n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acyl moieties.

Qualitatively similar results were obtained in a study of the structural requirements for acyl ethanolamide binding to the porcine brain cannabinoid receptor [10]. Binding was tested by displacement of a radiolabeled cannabinoid receptor agonist from porcine synaptsomal membranes. The Ki for anandamide binding was 39.2±5.7 nM, 8-times smaller than the Ki for synaptamide. Although these quantitative values differed from those obtained with the cloned human receptor [9], the results confirmed that synaptamide binding to the brain cannabinoid receptor was considerably weaker than anandamide binding.

Additional comparisons indicated that the Ki for synaptamide binding was 5-times larger than the Ki for docosatetraenoyl ethanolamide [10]. Likewise, the Ki for binding of eicosapentenoyl ethanolamide, the 20-carbon n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid analog, was 4-times larger than the Ki for anandamide binding. These results indicate that ethanolamides with n-3 fatty acyl groups bind to the brain cannabinoid receptor with lesser affinity than the corresponding congeners containing n-6 fatty acyl groups. Likewise, the binding of synaptamide to the recombinant human CB2 receptor overexpressed in HEK cells in a β-arrestin system was 10- to 50-fold weaker than the binding of anandamide [11].

The relatively weak binding of synaptamide suggests that its action probably is not mediated by cannabinoid receptors. Although synaptamide’s neuritogenic property resembles the function of some growth factors, there is no evidence at present for synaptamide binding to growth factor receptors. Identification of a high-affinity receptor would be an important step in elucidating the mechanism of action of synaptamide.

3. Endocannabinoid synthesis

Synaptamide biosynthesis was observed in a study comparing the utilization of various fatty acids for acyl ethanolamide synthesis in a bovine brain homogenate, but the amount formed was considerably less than that of anandamide [12]. P2 membranes containing 70 μg protein were suspended in Tris–HCl buffer, pH 9, and incubated with 20 mM ethanolamine and [14C]fatty acids. Anandamide synthesis increased from 600 to 1100 pmol/min mg protein when the [14C]arachidonic acid concentration was raised from 50 to 500 μM. The largest amounts of anandamide were formed by hippocampal membranes, but synthesis also occurred with membrane fractions prepared from the frontal cortex, thalamus and striatum. Much less synaptamide was synthesized by the P2 membranes, increasing from 120 to only 175 pmol/min mg protein over this range of [14C]DHA concentrations. [14C]Docosatetraenoic acid (22:4n-6), like [14C]DHA, was a poor substrate for acyl ethanolamide synthesis. By contrast, [14C]eicosatrienoic and [14C]eicosadienoic acid, 20-carbon n-6 fatty acids, were utilized almost as well as [14C]arachidonic acid. These results indicate that acyl ethanolamide synthesis in this brain membrane preparation is more effective with 20-carbon poly-unsaturated fatty acids than with the corresponding 22-carbon congeners.

Anandamide synthesis also was observed when rabbit brain microsomes or cytosol were incubated with 5 μM arachidonic acid and 50 mM ethanolamine [13]. Several other fatty acids, including DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid, were tested, but quantitative comparisons were not made. However, it is apparent from the thin layer chromatograms that the amounts of ethanolamide products synthesized from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and arachidonic acid were similar. By contrast, the synthesis of synaptamide from DHA was barely discernable. Taken together, these results suggest that the difference in fatty acid chain-length may be primarily responsible for the lesser capacity of brain preparations to synthesize synaptamide than anandamide.

Hippocampal neuron cultures prepared from mouse 18-day embryos converted [13C22]DHA to [13C22]synaptamide. The [13C22] synaptamide that was formed was recovered in both cell and culture medium. After incubation of 4.7 × 106 hippocampal neurons with 1 μM DHA for 3 days, the medium contained 313 ± 30 fmol nM [13C22]synaptamide, and the amount increased to 5560 ± 125 fmol when hydrolysis was blocked by addition of a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor [7].

3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes in culture synthesized synaptamide during incubation in DMEM medium containing 10% newborn calf serum and 10–50 μM DHA [14]. As noted with the hippocampal cultures [7], the synaptamide formed by the 3T3-L1 cells was recovered in the medium, and 70–150 pg/ml were produced during 24–48 h of incubation [14]. In similar incubations with EPA, the 3T3-L1 cells synthesized from 30- to 45-times more EPA ethanolamide, indicating that like the rabbit brain fractions [13], these pre-adipocytes also utilize EPA more effectively than DHA for acyl ethanolamide synthesis [14].

Anandamide and synaptamide were synthesized by a particulate fraction of bovine retina [15]. N-arachidonoyl phosphatidylethanolamine, an intermediate in the N-acylationphosphodiesterase pathway for anandamide biosynthesis [16], and N-docosahexaenoyl phosphatidylethanolamine, the corresponding DHA-containing intermediate, were present in the retina [15]. The retina also contained di-docosahexaenoyl phosphatidylcholine [17], a potential source of sn-1 DHA for transfer from phosphatidylcholine to the ethanolamine moiety of phosphatidylethanolamine to produce N-docosahexaenoyl phosphatidylethanolamine [18].

Human prostate and breast cancer cell lines synthesized acyl ethanolamides when incubated for 18 h in a medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 60–75 μM DHA or EPA [19]. Cell survival was 80% under these conditions. The prostate cancer cells synthesized 2.02±1.01–4.66±2.85 pmol/mg cell protein synaptamide and 0.75±0.49 pmol/mg cell protein EPA ethanolamide. Slightly higher levels were produced by the breast cancer cells. However, as opposed to the increase observed in the hippocampal incubations [7], the amounts formed by these malignant cells were not affected by inhibition of FAAH [19]. This suggests that hydrolysis by FAAH may not be a major step that regulates the synaptamide level in these cancer cells.

A key issue that remains to be determined is whether synaptamide, like anandamide, is synthesized from an N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine intermediate [20], and if so, which of the mechanisms that generate anandamide from this intermediate are operative in the synaptamide pathway [16,21,22]. Information about the metabolic processes that modulate this pathway would also improve our understanding on how synaptamide synthesis is regulated.

4. Metabolism

Two metabolic reactions have been reported for synaptamide, hydrolysis by FAAH and conversion to oxygenated products (Fig. 1). The FAAH expressed in the fetal brain hippocampus [7], retina [15], and prostate cancer cell lines [23] hydrolyzes synaptamide. However, comparative studies in the retina indicate that anandamide is a more effective substrate [15].

Conversion of synaptamide to oxygenated metabolites has been observed in brain and polymorphonuclear leukocytes [11]. The products detected in a mouse brain homogenate were 17-hydroxy-docosahexaenoylethanolamide (17-HDHEA) and 4,17-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoylethanolamide (4,17-diHDHEA). Poly-morphonuclear leukocytes produced these two products and three additional metabolites 7,17-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoylethanolamide (7,17-diHDHEA), 10,17-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoylethanolamide (10,17-diHDHEA) and 15-hydroxy, 16,17-epoxy-docosapentenoyl ethanolamide (15-HEDPEA). The initial step in the biosynthesis of these oxygenated metabolites, the conversion of synaptamide to 17-HDHEA, is catalyzed by a 15-lipoxygenase. The hydroxy-, di-hydroxy- and hydroxepoxy-metabolites are weak agonists for the human CB1 and CB2 receptors expressed in HEK cells [11]. Some of these oxygenated synaptamide metabolites have functional activity. 17-HDHEA and 15-HEDPEA at 10 nM concentrations inhibited IL-8-induced chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Furthermore, at concentrations between 0.01 and 10 nM, 10,17-diHDHEA inhibited platelet activating factor-stimulated platelet–leukocyte aggregate formation [11].

The fact that synaptamide is hydrolyzed by FAAH suggests that pharmacologic inhibition of this enzyme might enhance synaptamide-induced hippocampal development and cognitive function. In addition, metabolism of synaptamide to bioactive oxygenated products may further enhance biological effects of synaptamide in the brain.

5. Function and mechanism of action

Functional effects of synaptamide have been observed on cAMP formation, cytokine production, growth of prostate and breast cancer cells, and neural development. Synaptamide inhibited forskolin-mediated cAMP production (IC50 =6 μM) in CHO–HCR cells, but the inhibition produced by anandamide (IC50=160 nM) was 38-times more potent [9]. Lipopolysaccharide- induced IL-6 and MCP-1 production was suppressed by 10 nM synaptamide in 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes, suggesting that it may have anti-inflammatory properties in adipose tissue under physiological conditions [14]. Synaptamide decreased the viability of the LNCaP and PC3 prostate cancer cell lines (IC50=120–130 μM) grown in media containing 10% fetal bovine serum [23], but these concentrations probably exceed those that can occur physiologically. Likewise, the synaptamide concentrations that produce cell cycle arrest (IC50=9–66 μM) and apoptosis (IC50=24–43 μM) in these prostate cancer cell lines also are excessive, and these anti-proliferative actions of synaptamide in malignant cell lines are of questionable physiological relevance.

The synaptamide level in E-18 fetal hippocampi (155±35 fmol/μmol fatty acid, or 11.5±2.3 fmol/hippocampus) was significantly higher than the anandamide level (44±3 fmol/ μmol fatty acid or 4.4±0.8 fmol/hippocampus) although the amounts of DHA (6.7±0.7%) and arachidonic acid (6.1±0.5%) in the hippocampus are comparable [24]. This relatively high content suggests that synaptamide might have important functions in the hippocampus. Consistent with this possibility, studies by Kim et al. indicated that synaptamide stimulated neurite growth, synaptogenesis and synaptic protein expression in developing hippocampal neurons [7]. Furthermore, the stimulatory effect of DHA on these processes was potentiated by inhibition of FAAH. Additional studies demonstrated that the cultured hippocampal neurons synthesized [13C22]synaptamide during incubation with [13C22]DHA. Taken together, these results suggested that the effects of DHA on neurite extension and synaptogenesis might be mediated by its conversion to synaptamide. This possibility was supported by studies showing that 10–100 nM synaptamide increased hippocampal neurite growth and synaptogenesis—concentrations that are substantially lower than those of DHA (0.5–1 μM) necessary to produce these effects [7,8]. Further support for this hypothesis was provided by findings that the expression of synapsin and glutamate receptor subunits, and glutamatergic synaptic activity, increased when the hippocampal neurons were treated with 100 nM synaptamide [7].

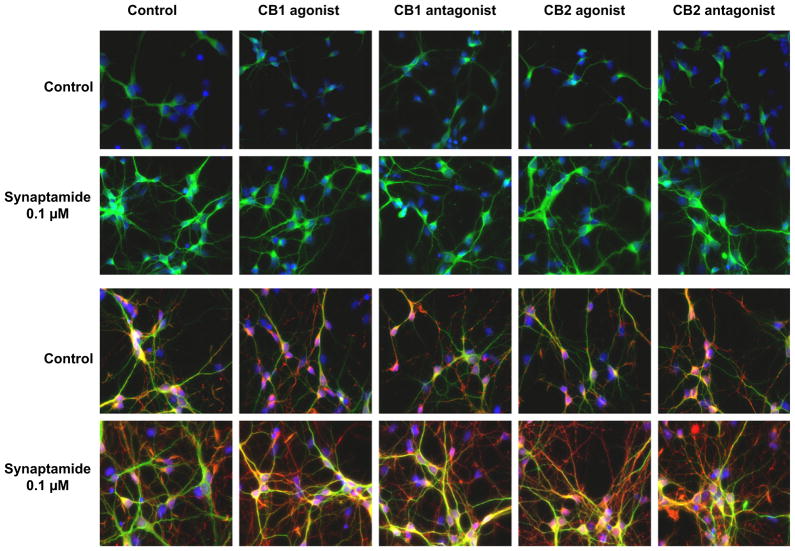

The observed synaptamide effects on hippocampal neuronal development are not affected by CB1 and CB2 agonists or antagonists (H.S. Moon and H.Y. Kim, unpublished data, Fig. 2). In addition, anandamide at concentrations as high as 1–1.5 μM does not stimulate neurite growth or synaptogenesis in cultured embryonic hippocampal neurons [7,8]. Furthermore, the binding of synaptamide to the brain cannabinoid receptor is 8- to 25-times weaker than anandamide binding [9,10], and synaptamide binding to the CB2 cannabinoid receptor is 10- to 50-fold weaker than anandamide binding [11]. These results indicate that synaptamide promotes neurite growth and synaptogenesis by a cannabinoid-independent mechanism. The finding that newly synthesized synaptamide is recovered in the medium may indicate that it acts as a ligand for a membrane-bound receptor that mediates its mechanism of action. However, an intracellular mechanism of action cannot be excluded because of the recent finding that cytosolic fatty acid binding proteins, including the brain fatty acid binding protein, bind acyl ethanolamides and transport them to activate nuclear receptors [25].

Fig. 2.

Cannabinoid-independent function of synaptamide. Neither agonists nor antagonists of CB1 and CB2 influence the neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in developing hippocampal neurons. Neurite growth is visualized by MAP2 (green) with DAPI staining for nuclei on both 3 and 7 days in vitro (DIV). Synaptogenesis is represented by synapsin-positive puncta (red) on day 7 cultures. HU210, CB1 agonist; JHW015, CB2 agonist; SR141716A, CB1 antagonist; SR144528, CB2 antagonist. (H.S. Moon and H.Y. Kim, unpublished data). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Studies on the mechanism of action of DHA in the nervous system initially emphasized changes in membrane physical properties and the resulting effects on signaling proteins interacting with [26] or embedded in DHA-rich membrane domains [27]. Subsequent work has focused attention on the production of bioactive DHA metabolites, including neuroprotectin D1 that protects against neuronal apoptosis and limits brain injury [28] as well as synaptamide. The stimulatory actions of synaptamide on neurite growth and synaptogenesis suggest that it also may contribute to the neuroprotective effects of DHA by improving neuronal repair after injury. Therefore, it is possible that synaptamide has a role in not only neural development but also neuroprotection.

6. Dietary modulation of the brain acyl ethanolamide content

The acyl ethanolamide content and composition of the brain can be altered by changes in dietary polyunsaturated fatty acid intake. Brain homogenates prepared from piglets fed diets supplemented with either arachidonic acid or DHA for the first 18 days of life contained 4-times more anandamide and 9-times more synaptamide, respectively, than brains from piglets fed the corresponding unsupplemented diet [29]. The levels of arachidonic acid and DHA in the supplemented diets were similar to those in porcine milk. DHA supplementation for 2 weeks also increased the synaptamide content of mouse brain by 22% (from 3.77±0.66 to 4.62±0.74 ng/g), accompanied by a quantitatively similar reduction in the anandamide content by 22% [30]. The diet containing DHA also produced a small increase in the synaptamide content of the plasma in these mice.

As opposed to these data indicating that the synaptamide content in the brain increases when the diet is supplemented with DHA, a diet containing fish oil fed to rats for 1 week did not alter the content of acyl ethanolamides. However, the DHA content in the brain was not altered, either, after this short-term feeding [31].

An important finding regarding dietary lipid effects on brain development is that the level of synaptamide in fetal mouse hippocampi decreased by more than 80% when omega-3 fatty acids were removed from the maternal diet [7]. While the anandamide content was not significantly affected, a compensatory increase of docosapentaenoyl ethanolamide occurred in these hippocampi, from non-detectable level to 69.2±22.8 fmol/μmol fatty acid or 4.5±1.7 fmol/hippocampus. These changes in acyl ethanolamide levels were accompanied by similar changes in the total fatty acid composition of the brain. The fact that the brain synaptamide content is dependent on the maternal dietary DHA intake provides a potential mechanism through which adequate omega-3 fatty acid intake facilitates optimal brain development during gestation.

No information is presently available regarding whether these dietary DHA effects on the synaptamide content in the hippocampus or other regions of the brain are age-dependent, or whether they might be affected by neurodegenerative diseases.

7. Nomenclature

Thus far, five terms have been used in the literature for this DHA derivative, N-docosahexanoyl ethanolamine, docosahexanoylethanolamide, synaptamide, and the abbreviations DHEA and DEA. This has led to some confusion, especially with regard to DHEA which has been the widely used abbreviation for the adrenal steroid hormone dihydroxyepiandrosterone. The term ‘synaptamide’ for N-docosahexanoylethanolamine is consistent with the term ‘anandamide’ established for N-arachidonylethanolamine in that both represent the function and the chemical structure of the amide bond in the respective compounds [5]. It is also anticipated that more synaptamide-derived novel bioactive compounds other than the oxygenated compounds already reported will soon emerge. Therefore, to facilitate communication and obviate further nomenclature problems, we suggest that the synaptamide-based term be used for its derivatives; for example, 17-hydroxysynaptamide, 10,17-dihydroxy-ynaptamide, etc. As in the case of other biomediators, the term synaptamide would not imply that the biosynthesis and biological actions of synaptamide or its derivatives are limited to the nervous system; for example, use of the term prostaglandins does not imply that these biomediators only are synthesized and exert biological effects in the prostate gland.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural program of NIAAA, NIH.

References

- 1.Howlett AC, Fleming RM. Cannabinoid inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Pharmacology of the response in neuroblastoma cell membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:532–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devane WA, Dysarz WA, III, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;34:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechoulam R. Discovery of endocannabinoids and some random thoughts on their possible roles in neuroprotection and aggression. Prostaglandins Leuketrienes Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:93–99. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee PG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Ettinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanus L, Gopher A, Almog S, Mechoulam R. Two new unsaturated fatty acid ethanolamides in brain that bind to the cannabinoid receptor. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3032–3034. doi: 10.1021/jm00072a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HY, Moon SY, Cao D, Lee J, Jun SB, Lovinger DM, Abkar M, Huang BX. N-docosahexaenoylethanolamide promotes development of hippocampal neurons. Biochem J. 2011;435:327–336. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HY, Spector AA, Xiong ZM. A synaptogenic amide N-docosahexaenoylethanolamide promotes hippocampal development. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators. 2011;96:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felder CC, Briley EM, Simpson JT, Mackie K, Devane WA. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabimimetic eicosanoid, binds to the cloned human cannabinoid receptor and stimulates receptor-mediated signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7656–7660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheskin T, Hanus L, Slager J, Vogel Z, Mechoulam R. Structural requirements for binding of anandamide-type compounds to the brain cannabinoid receptor. J Med Chem. 1997;40:659–667. doi: 10.1021/jm960752x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang R, Fredman G, Krishnamoorthy S, Agrawal N, Irimia D, Piomelli D, Serhan CN. Decoding functional metabolomics with docosahexaenoylethanolamide (DHEA) identifies novel bioactive signals. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31532–31541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devane WA, Axelrod J. Enzymatic synthesis of anandamide, and endogenous ligand for the cannabinoid receptor, by brain membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6698–6701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruszka KK, Gross RW. The ATP- and CoA-independent synthesis of arachidonoylethanolamide. A novel mechanism underlying the synthesis of the endogenous ligand of the cannabinoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14345–14348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balvers MGJ, Verhoeckx KCM, Plastina P, Worteboer HM, Meijerink J, Witkamp RF. Docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid are converted by 3T3-L1 adipocytes to N-acyl ethanolamines with anti-inflammatory properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bisogno T, Delton-Vandenbroucke I, Milone A, Lagarde M, DiMarzo V. Biosynthesis and inactivation of N-arachidonoylethanolamide (anandamide) and N-docosahexaenoylethanolamide in bovine retina. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;370:300–307. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid HHO, Schmid PC, Natarajan V. The N-acylationphosphodiesterase pathway and cell signaling. Chem Phys Lipids. 1996;80:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(96)02554-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu SL, Mitchell DC, Lim SY, Wen ZM, Kim HY, Salem N, Jr, Litman BJ. Reduced G protein-coupled signaling efficiency in retinal rod outer segments in response to n-3 fatty acid deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31098–31104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid HHO, Schmid PC, Natarajan V. N-acylated glycerophospholipids and their derivatives. Prog Lipid Res. 1990;29:1–43. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(90)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown I, Wahle KWJ, Cascio MG, Smoum-Jaouni R, Mechoulam R, Pertwee RG, Heys SD. Omega-3 N-acylethanolamines are endogenously synthesized from omega-3 fatty acids in different human prostate and breast cancer cell lines. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essent Fatty Acids. 2011;85:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadas H, di Tomaso E, Piomelli D. Occurrence and biosynthesis of endogenous cannabinoid precursor, N-arachidonoyl phosphatidylethanolamine, in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1226–1242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01226.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Anandamide biosynthesis catalyzed by the phosphodiesterase GDE1 and detection of glycerophospho-N-acylethanolamine precursors in mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9341–9349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Tonegawa T, Nakane S, Yamasita A, Ishima Y, Waku K. Transacylation-mediated and phosphodiesterase-mediated synthesis of N-arachidonoylethanolamine, an endogenous cannabinoid ligand, in rat brain microsomes: comparison and synthesis from free arachidonic acid and ethanolamine. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0053h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown I, Cascio MG, Wahle KWJ, Smoum R, Mechoulam R, Ross RA, Pertwee RG, Heys SD. Cannabinoid receptor-dependent and -independent anti-proliferative effects of omega-3 ethanolamides in androgen receptor-positive and -negative prostate cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1584–1591. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao D, Kevala K, Kim J, Moon HS, Jun SB, Lovinger D, Kim HY. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes hippocampal neuronal development and synaptic function. J Neurochem. 2009;111:510–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaczocha M, Vivieca S, Sun J, Glaser ST, Deutsch DG. Fatty acid-binding proteins transport N-acylethanolamines to nuclear receptors and are targets of endocannabinoid transport inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3415–3424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akbar M, Calderon F, Wen Z, Kim HY. Docosahexaenoic acid: a positive modulator of Akt signaling in neuronal survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10858–10863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502903102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litman B, Niu SL, Polozova A, Mitchell DC. The role of docosahexaenoic acid in modulating G-protein coupled signaling pathways: visual transduction. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16:237–242. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Marcheselli VL, Bodker A, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. A role for docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2774–2787. doi: 10.1172/JCI25420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger A, Crozier G, Bisogno T, Cavaliere P, Innis S, DiMarzo V. Anandamide and diet: inclusion of dietary arachidonate and docosahexaenoate leads to increased brain levels of the corresponding N-acylethanolamines in piglets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6402–6406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101119098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood JT, Williams JS, Pandarinathan L, Janero DR, Lammi-Keefe CJ, Makiyannis A. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid supplementation alters select physiological endocannabinoid-system metabolites in brain and plasma. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1416–1423. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artmann A, Petersen G, Hellgren LI, Boberg J, Skonberg C, Nellemann C, Hansen SH, Hansen HS. Influence of dietary fatty acids on endocannabinoid and N-acylethanolamine levels in rat brain, liver and small intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]