Abstract

Objectives. To assess the current clinical evidence of Banxia Baizhu Tianma Decoction (BBTD) for essential hypertension (EH). Search Strategy. Electronic databases were searched until July 2012. Inclusion Criteria. We included randomized clinical trials testing BBTD against placebo, antihypertensive drugs, or combined with antihypertensive drugs against antihypertensive drugs. Data Extraction and Analyses. Study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and data analyses were conducted according to Cochrane standards. Results. 16 randomized trials were included. Methodological quality of the included trials was evaluated as generally low. 2 trials compared prescriptions based on BBTD using alone with antihypertensive drugs. Meta-analysis showed no significant effect of modified BBTD compared with captopril in systolic blood pressure (MD: −0.75 (−5.77, 4.27); P = 0.77) and diastolic blood pressure (MD: −0.75 (−2.89, 1.39); P = 0.49). 14 trials compared the combination of BBTD or modified BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs with antihypertensive drugs. Meta-analysis showed there are significant beneficial effect on systolic blood pressure in the combination group compare to the antihypertensive drugs (MD: −4.33 (−8.44, −0.22); P = 0.04). The safety of BBTD is uncertain. Conclusions. There is encouraging evidence of BBTD for lowering SBP, but evidence remains weak. Rigorously designed trials are warranted to confirm these results.

1. Introduction

Hypertension is an increasingly important medical and public health issue, which could lead to severe complications [1]. High blood pressure is a major, independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The relationship between blood pressure (BP) and risk of CVD events is continuous, consistent, and independent of other risk factors. The higher the BP, the greater is the chance of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and kidney diseases. The prevention and management of hypertension are major public health challenges. Much of hypertension, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases would be preventable if the rise in BP with age could be prevented or diminished [2].

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is becoming increasingly popular and frequently used among patients with CVD [3–7]. Approximately 50% of US residents use some form of alternative medicine; 10% use it for their children [8]. Recent researches showed that CAM (also integrative medicine) could contribute to blood pressure control [9–12]. Chinese medicine (CM) [13, 14], including herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion, and cupping Tai chi and Qigong, as one of the most important parts in CAM, is thought to be effective for the treatment of essential hypertension [15–18]. It has been considered as an effective adjunct treatment by either physicians or patients in China. More and more patients firstly select the combination therapy, just CM combined with antihypertensive drugs, for better efficacy both in BP and clinical symptom such as headache, neck and shoulder pain, dizziness, and fatigue. For seeking the best evidence of CM in making decisions for hypertensive patients, an increasing number of systematic reviews (SR) and meta-analysis have been conducted to assess the efficiency of CM for hypertension [19–24]. It is found out that CM could contribute to lower BP smoothly, recover the circadian rhythm of BP, and improve symptoms and signs especially [25]. And the efficacy of CM for treating hypertension is suggested by a large number of published case series and randomized trials [26, 27], although some trials have demonstrated negative results [28, 29]. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that the antihypertensive effect is related to activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [30, 31], regulation of vascular endothelium function [26, 32], inhibiting proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts and collagen synthesis [33], inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [34], and so forth. A series of Chinese herbs have been authorized recommended by the Chinese government in Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China (2010 edition).

Banxia baizhu tianma decoction (BBTD), containing eight commonly used herbs (Pinellia ternata, atractylodes macrocephala, Gastrodia elata, tangerine peel, poria cocos, Glycyrrhiza, ginger, and red jujube), is a classical Chinese herbal formula noted in Medical Revelations in Qing dynasty. It has been widely used to treat hypertension-related symptoms in clinical practice for centuries in China [25]. The most common symptoms include headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting, which belong to the liver yang hyperactivity and fluid retention syndrome [25]. The mechanism of the prescription maybe calming liver, suppressing liver yang hyperactivity, dissipating excessive fluid, and expelling phlegm according to the theory of TCM. Recently, modern researches showed that BBTD have potential effect of lowing BP in vitro and in vivo [25, 35–38]. Biochemically, BBTD also showed good effect in improving the mesenteric endothelial dysfunction and the hemodynamic parameters, inhibiting the expression of nitric oxide (NO) and interleukin-1 (IL-1), decreasing serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TGs), and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), regulating rennin-angiotensin system (RAS), and improving the oxidative stress state, so as to lower the arterial pressure [35–38].

Currently, BBTD used alone or combined with antihypertensive drugs has been widely used as an alternative and effective method for the treatment of essential hypertension in China. And until now a number of clinical studies of BBTD reported the clinical effect ranging from case reports and case series to controlled observational studies and randomized clinical trials. However, there is no critically appraised evidence such as systematic reviews or meta analyses on potential benefits and harms of BBTD for essential hypertension to justify their clinical use and their recommendation. This paper aims to assess the current clinical evidence of BBTD for essential hypertension.

2. Methods

2.1. Database and Search Strategies

Literature searches were conducted in Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (July 2012). We also searched the reference list of retrieved papers. Databases in Chinese were searched to retrieve the maximum possible number of trials of BBTD for essential hypertension because BBTD is mainly used and researched in China. All of those searches ended on 3 July, 2012. Ongoing registered clinical trials were searched in the website of Chinese clinical trial registry (http://www.chictr.org/) and international clinical trial registry by US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/). The following search terms were used individually or combined: “hypertension,” “essential hypertension,” “banxia baizhu tianma decoction,” “clinical trial,” and “randomized controlled trial.” The bibliographies of included studies were searched for additional references.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

All the parallel randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of all the prescriptions based on “banxia baizhu tianma decoction” compared with antihypertensive drugs in patients with hypertension were included. RCTs combined banxia baizhu tianma decoction with antihypertensive drugs compared with antihypertensive drugs and all the modified banxia baizhu tianma decoction were included as well. According to the principle of the similarity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) formula [39], the number of modified herbs should not be more than 4, so that to ensure the similarity is greater than or equal to 0.5. And the key herbs in the modified banxia baizhu tianma decoction should include Pinellia ternata, atractylodes macrocephala, Gastrodia elata, and poria cocos, according to the theory of TCM. There were no restrictions on population characteristics, language and publication type. The main outcome measure was blood pressure. Duplicated publications reporting the same groups of participants were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors conducted the literature searching (Xiong and Yang), study selection (Xiong and Wang), and data extraction (Xiong and Li) independently. The extracted data included authors, title of study, year of publication, study size, age and sex of the participants, details of methodological information, name and component of Chinese herbs, treatment process, details of the control interventions, outcomes, and adverse effects for each study. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and reached consensus through a third party (J. Wang).

The methodological quality of trials was assessed independently using criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 (Xiong and Yang) [56]. The items included random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other bias. The quality of all the included trials was categorized to low/unclear/high risk of bias (“yes” for a low of bias, “no” for a high risk of bias, “unclear” otherwise). Then trials were categorized into three levels: low risk of bias (all the items were in low risk of bias), high risk of bias (at least one item was in high risk of bias), unclear risk of bias (at least one item was in unclear).

2.4. Data Synthesis

RevMan 5.1 software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration was used for data analyses. Continuous outcome will be presented as mean difference (MD) and its 95% CI. Heterogeneity was recognized significant when I 2 ≥ 50%. Fixed-effects model was used if there is no significant heterogeneity of the data; random-effects model was used if significant heterogeneity existed (50% < I 2 < 85%). Publication bias would be explored by funnel plot analysis if sufficient studies were found.

3. Result

3.1. Description of Included Trials

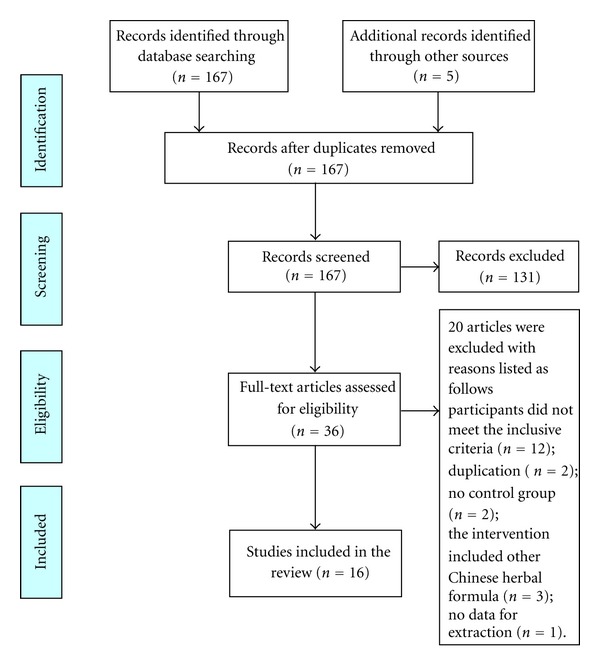

A flow chart depicted the search process and study selection (as shown in Figure 1). After primary searches from the databases, 167 articles were screened. After reading the titles and abstracts, 131 articles of them were excluded. Full texts of 36 articles were retrieved, and 20 articles were excluded with reasons listed as follows: participants did not meet the inclusive criteria (n = 12), duplication (n = 2), no control group (n = 2), the intervention included other Chinese herbal formula (n = 3), and no data for extraction (n = 1). In the end, 16 RCTs [40–55] were included. All the RCTs were conducted in China and published in Chinese. The characteristics of included trials were listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics and methodological quality of included studies.

| Study ID | Sample | Diagnosis standard |

Intervention | Control | Course (week) | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng, 2011 [40] | 60 | CGMH-2005 | Modified BBTD (600 mL/d#) | Enalapril (10 mg qd) | 3 | BP; adverse effect |

| Xiong, 2010 [41] | 60 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (250 mL/d#) plus L-amlodipine (2.5 mg qd) | L-amlodipine (2.5 mg qd) | 4 | BP |

| Chen et al., 2005 [42] | 70 | Hypertension diagnostic criteria (unclear); CDTDSS | Modified BBTD (240 mL/d#) plus nitrendipine (no detailed information) | Nitrendipine (no detailed information) | 8 | BP |

| Wang, 2001 [43] | 100 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH | Modified BBTD (1 dose/d#) plus captopril (25–37.5 mg tid) | Captopril (25–37.5 mg tid) | 4 | BP |

| Che et al., 2011 [44] | 60 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; TCM diagnostic criteria (unclear) | Modified BBTD (400 mL/d#) plus nifedipine controlled release tablet (10 mg bid) | Nifedipine controlled release tablet (10 mg bid) | 4 | BP; adverse effect |

| Jin, 2011 [45] | 60 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs (400 mL/d#) | Antihypertensive drugs (no detailed information) | 6 | BP; adverse effect |

| Chen, 2007 [46] | 120 | CGPMHBP-2004; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (1 dose/d#) plus losartan (50 mg qd) | Losartan (50 mg qd) | 12 | BP |

| Guo, 2009 [47] | 94 | CGPMHBP-2004; CIM | Modified BBTD (400–500 mL/d#) plus compound reserpine-triamterene tablets (1 pill, qd) | Compound reserpine-triamterene tablets (1 pill, qd) | 4 | BP |

| Li, 2011 [48] | 139 | Hypertension and TCM diagnostic criteria (unclear) | Modified BBTD (450 mL/d#) plus felodipine sustained release tablets (1 pill, bid)/levamlodipine besylate tablets (1 pill, qd) | Felodipine sustained release tablets (1 pill, bid)/levamlodipine besylate tablets (1 pill, qd) | 12 | BP |

| Guo et al., 2006 [49] | 116 | 1999 WHO—ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (250 mL/d#) plus levamlodipine besylate tablets (5 mg qd) | Levamlodipine besylate tablets (5 mg qd) | 2 | BP |

| Zhou, 2008 [50] | 102 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (400 mL/d#) plus nifedipine sustained release tablets (10 mg bid) | Nifedipine sustained release tablets (10 mg bid) | 4 | BP; adverse effect |

| Wu et al., 2007 [51] | 87 | CGMH-1999; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (1 dose/d#) plus antihypertensive drugs (no detailed information) | Antihypertensive drugs (no detailed information) | 8 | BP |

| Lei and Lin, 2009 [52] | 114 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | BBTD (400 mL/d#) plus benazepril (10 mg qd) | Benazeprill (10 mg qd) | 4 | BP |

| Liu et al., 2007 [53] | 80 | 1999 WHO—ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (300 mL/d#) | Captopril (12.5 mg bid) | 4 | BP |

| Zhang, 2002 [54] | 80 | JNC-VI | Modified BBTD (1 dose/d#) plus felodipine (5 mg qd)/hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg bid) | Felodipine (5 mg qd)/hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg bid) | 1 | BP |

| Wang, 2005 [55] | 82 | 1999 WHO—ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | Modified BBTD (1 dose/d#) plus captopril (no detailed information) | Captopril (no detailed information) | 4 | BP |

1424 patients with essential hypertension were included. There was a wide variation in the age of subjects (19–78 years). Sixteen (16) trials specified five diagnostic criteria of hypertension, five trials [40, 41, 45, 50, 52] used Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension-2005 (CGMH-2005), five trials [43, 44, 49, 53, 55] used 1999 WHO-ISH guidelines for the management of hypertension (1999 WHO-ISH GMH), two trials [46, 47] used China Guidelines on Prevention and Management of High Blood Pressure-2004 (CGPMHBP-2004), one trial [51] used Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension-1999 (CGMH-1999), one trial [51] used the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-VI), and two trials [42, 48] only demonstrated patients with essential hypertension. Sixteen (16) trials specified three diagnostic criteria of abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome in TCM, nine trials [41, 45, 46, 49–53, 55] used Guidelines of Clinical Research of New Drugs of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GCRNDTCM), one trial [42] used Convention of Diagnosis and Treatment of Disease and Syndrome in Shanghai (CDTDSS), one trial [47] used Chinese internal medicine (CIM), two trials [44, 48] only demonstrated patients with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome in TCM, and three trials [40, 43, 54] did not report any TCM diagnostic criteria.

Interventions included all the prescriptions based on “banxia baizhu tianma decoction” alone, or combined with antihypertensive drugs. The controls included antihypertensive drugs alone. Two trials investigated the prescriptions based on “banxia baizhu tianma decoction” used alone [40, 53] versus antihypertensive drugs, and the rest fourteen trials [41–52, 54, 55] compared the prescriptions based on “banxia baizhu tianma decoction” plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs.

The total treatment duration ranged from 7 days to 3 months. The variable prescriptions are presented in Table 1. The different compositions of Chinese herbal formula BBTD are presented in Table 2. All of the 16 trials used the BP as the outcome measure. Adverse effect was described in detail.

Table 2.

Composition of formula.

| Study ID | Formula | Composition of formula |

|---|---|---|

| Zheng, 2011 [40] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 9 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 10 g, poria cocos 10 g, Glycyrrhiza 4 g, ginger 2 pieces, red jujube 5, grass leaved sweetflag 10 g, ligusticum chuanxiong hort 9 g, alisma orientalis 15 g, and Grifola umbellata 10 g |

| Xiong, 2010 [41] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 12 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 15 g, tangerine peel 12 g, poria cocos 12 g, alisma orientalis 15 g, plantain seed 15 g, bamboo bark 9 g, villous amomum fruit 3 g, Pinellia pedatisecta Schott 12 g, grass leaved sweetflag 15 g, ginger 9 g, red jujube 5, and Glycyrrhiza 6 g |

| Chen et al., 2005 [42] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 6 g, Gastrodia elata 9 g, atractylodes macrocephala 9 g, poria cocos 12 g, tangerine peel 12 g, Pinellia pedatisecta Schott 12 g, fructus aurantii 12 g, Glycyrrhiza 6 g |

| Wang, 2001 [43] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 15 g, atractylodes macrocephala 12 g, Gastrodia elata 15 g, tangerine peel 12 g, poria cocos 12 g, alisma orientalis 15 g, Uncaria 15 g (put in later), abalone shell 15 g (decocting first), ginger 15 g, jujube 5, and Glycyrrhiza 6 g |

| Che et al., 2011 [44] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 15 g, atractylodes macrocephala 25 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 10 g, poria cocos 10 g, kudzu root 10 g, Sophora flower 15 g, cassia seed 10 g, hawthorn 15 g, and Glycyrrhiza 5 g |

| Jin, 2011 [45] | BBTD | Pinellia ternate 10 g, atractylodes macrocephala 10 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 10 g, poria cocos 15 g, Glycyrrhiza 5 g, ginger 10 g, and jujube 10 g |

| Chen, 2007 [46] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 9 g, atractylodes macrocephala 12 g, Gastrodia elata 6 g, tangerine peel 10 g, poria cocos 15 g, alisma orientalis 10 g, hawthorn 10 g, cassia seed 15 g, grass leaved sweetflag 6 g, ligusticum chuanxiong hort 6 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza 12 g, and Glycyrrhiza 5 g |

| Guo, 2009 [47] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 12 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 9 g, poria cocos 10 g, ligusticum chuanxiong hort 10 g, officinal magnolia bark 6–10 g, chrysoidine 9 g, grass leaved sweetflag 10 g, curcuma longa 10 g, ginger 3 pieces, and jujube 3 |

| Li, 2011 [48] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 10 g, atractylodes macrocephala 10 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 12 g, poria cocos 15 g, citrus aurantium 10 g, bamboo bark 10 g, and Glycyrrhiza 6 g |

| Guo et al., 2006 [49] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 18 g, atractylodes macrocephala 12 g, Gastrodia elata 18 g, tangerine peel 12 g, poria cocos 15 g, grass leaved sweetflag 15 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 15 g, Prunella vulgaris 12 g, Glycyrrhiza 6 g, and jujube 5 |

| Zhou, 2008 [50] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 12 g, atractylodes macrocephala 12 g, Gastrodia elata 6 g, tangerine peel 9 g, poria cocos 12 g, bamboo bark 9 g, Glycyrrhiza 6 g, villous amomum fruit 3 g, ginger 3 g, and jujube 5 |

| Wu et al., 2007 [51] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 10 g, atractylodes macrocephala 10 g, Gastrodia elata 10 g, tangerine peel 10 g, poria cocos 15 g, bamboo bark 10 g, Coix lacryma-jobi 20 g, Glycyrrhiza 3 g, and ginger 3 pieces |

| Lei and Lin, 2009 [52] | BBTD | Pinellia ternate 12 g, atractylodes macrocephala 12 g, Gastrodia elata 15 g, tangerine peel 9 g, poria cocos 12 g, Glycyrrhiza 6 g, ginger 3 g, and jujube 5 |

| Liu et al., 2007 [53] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 9 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 6 g, tangerine peel 6 g, poria cocos 6 g, Glycyrrhiza 5 g, angelica sinensis 10 g, white peony root 10 g, lotus leaf 15 g, and alisma orientalis 15 g |

| Zhang, 2002 [54] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 15 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 12 g, tangerine peel 12 g, poria cocos 12 g, Glycyrrhiza 10 g, plantain seed 15 g, and Loranthus parasiticus 15 g |

| Wang, 2005 [55] | Modified BBTD | Pinellia ternate 10 g, atractylodes macrocephala 15 g, Gastrodia elata 15 g, tangerine peel 15 g, poria cocos 30 g, hawthorn 15 g, and grass leaved sweetflag 15 g |

3.2. Methodological Quality of Included Trials

The majority of the included trials were assessed to be of general poor methodological quality according to the predefined quality assessment criteria (Table 3). The randomized allocation of participants was mentioned in all trials; however, only 5 trials stated the methods for sequence generation including random number table [40, 44, 46, 54] and drawing [48]. Insufficient information was provided to judge whether or not it was conducted properly. Allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, and blinding of outcome assessment were not mentioned in all trials. None of trials reported dropout or withdraw. None of trials had a pretrial estimation of sample size. All the trials did not mention followup. We tried to contact the author for further information; however, no information has been provided to date.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included randomized controlled trials.

| Included trials | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng, 2011 [40] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Xiong, 2010 [41] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Chen et al., 2005 [42] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Wang, 2001 [43] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Che et al., 2011 [44] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Jin, 2011 [45] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | High |

| Chen, 2007 [46] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Guo, 2009 [47] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Li, 2011 [48] | Drawing | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Guo et al., 2006 [49] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Zhou, 2008 [50] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | High |

| Wu et al., 2007 [51] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Lei and Lin, 2009 [52] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Liu et al., 2007 [53] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Zhang, 2002 [54] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Wang, 2005 [55] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

3.3. Effect of the Interventions

3.3.1. “Banxia Baizhu Tianma Decoction” versus Antihypertensive Drugs (Western Medicine)

Two trials [40, 53] compared prescriptions based on BBTD used alone with antihypertensive drugs. A change in blood pressure was reported in all the two RCTs [40, 53]. One trial [53] showed the homogeneity in the consistency of the trial results. Thus, fixed-effects model should be used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed no significant effect of modified BBTD compared with captopril alone in systolic blood pressure (MD: −0.75 (−5.77, 4.27); P = 0.77) and diastolic blood pressure (MD: −0.75 (−2.89, 1.39); P = 0.49) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Analyses of systolic blood pressure.

| Trials | MD (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBTD versus antihypertensive drugs | |||

| Modified BBTD versus captopril | 1 | −0.75 (−5.77, 4.27) | 0.77 |

|

| |||

| Meta-analysis | 1 | −0.75 (−5.77, 4.27) | 0.77 |

|

| |||

| BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | |||

| Modified BBTD plus L-amlodipine versus L-amlodipine | 1 | −0.13 (−4.93, 4.67) | 0.96 |

| Modified BBTD plus losartan versus losartan | 1 | −7.38 (−9.95, − 4.81) | <0.00001 |

| Modified BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | 1 | −4.31 (−8.39, − 0.23) | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Meta-analysis | 3 | −4.33 (−8.44, − 0.22) | 0.04 |

Table 5.

Analyses of diastolic blood pressure.

| Trials | MD (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBTD versus antihypertensive drugs | |||

| Modified BBTD versus captopril | 1 | −0.75 (−2.89, 1.39) | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| Meta-analysis | 1 | −0.75 (−2.89, 1.39) | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | |||

| Modified BBTD plus L-amlodipine versus L-amlodipine | 1 | 1.55 (−2.39, 5.49) | 0.44 |

| Modified BBTD plus losartan versus losartan | 1 | −3.85 (−5.70, − 2.00) | <0.0001 |

| Modified BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | 1 | −1.24 (−4.04, 1.56) | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| Meta-analysis | 3 | −1.57 (−4.54, 1.40) | 0.30 |

3.3.2. “Banxia Baizhu Tianma Decoction” Plus Antihypertensive Drugs versus Antihypertensive Drugs

Fourteen trials [41–52, 54, 55] compared the combination of BBTD or modified BBTD plus antihypertensive drugs with antihypertensive drugs. A change in blood pressure was reported in all the included RCTs.

Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) —

The 3 independent trials [41, 46, 51] did not show homogeneity in the trial results, chi-square = 7.18, (P = 0.03); I 2 = 72%. Thus, random-effects model should be used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed that there are significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to the antihypertensive drugs used alone (MD: −4.33 (−8.44, −0.22); P = 0.04) (Table 4).

Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP) —

Three trials [41, 46, 51] did not show homogeneity in the trial results, chi-square = 6.87, (P = 0.03); I 2 = 71%. Thus, random-effects model should be used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed that there are no significant beneficial effect on the combination group compare to the antihypertensive drugs used alone (MD: −1.57 (−4.54, 1.40); P = 0.30) (Table 5).

3.4. Publication Bias

The number of trials was too small to conduct any sufficient additional analysis of publication bias.

3.5. Adverse Effect

Four out of sixteen trials mentioned the adverse effect [40, 44, 45, 50]. Four trials reported five specific symptoms including headache, distending feeling in head, palpitations, drowsiness, and fatigue. Among them, no adverse events were found in two trials [44, 45]. One trial reported adverse effect in enalapril group including headache, palpitations, drowsiness, and fatigue [40]. One trial mentioned adverse effect both in modified BBTD plus nifedipine sustained release tablets group and nifedipine sustained release tablets group including distending feeling in head [50].

4. Discussion

Based on the paper and meta-analyses of the outcome on either SBP or DBP, BBTD may have positive effects for lowing BP. BBTD as an adjunctive treatment to antihypertensive drugs significantly lowered SBP in patients with hypertension. However, according to potential publication bias and low-quality trials, available data are not adequate to draw a definite conclusion of BBTD for essential hypertension. And the positive findings should be interpreted conservatively.

Several limitations should be considered before accepting the findings of this paper. First, the quality of the included RCTs is generally low. Sixteen trials included in this paper had risk of bias in terms of design, reporting, and methodology. They provided only inadequate reporting of study design, allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, intention to treat analysis, and dropouts account in the majority of trials. Randomization was mentioned but without further details, which do not allow a proper judgment of the conduct of the trials. All the trials did not describe the blinding in details. It directly led to performance bias and detection bias due to patients and researchers being aware of the therapeutic interventions for the subjective outcome measures. All the sixteen RCTs prohibited us to perform meaningful sensitivity analysis. All the included trials were not multicenter, large-scale RCTs. If poorly designed, all the trials would show larger differences compared with well designed trials.

Second, all the sixteen trials did not report the adverse effect of banxia baizhu tianma decoction. Therefore, a conclusion about the safety of BBTD cannot be made clearly. In China, it is widely believed that it is safe to use herbal medicines for various diseases. With more and more reports of adverse effects of Chinese herbal medicines, the safety of Chinese herbs and formulae needs to be monitored rigorously and reported appropriately in the future clinical trials.

Third, Vickers et al. demonstrated that some countries, for example, China, generate virtually no “negative” studies at all [57]. In other words, publication and other biases may play an important role. We only identified and included trials published in Chinese after conducting comprehensive searches. Most of the trials are small sample with positive findings. We tried to avoid language bias and location bias, but we cannot exclude potential publication bias.

Fourth, it is pointed out that, lacking Chinese medicine (CM) pattern criteria (also called syndrome or zheng) become the key issue both for RCT and clinical practice [58–60]. For example, receiving CM or conventional therapies in patients with the same disease respectively, conventional treatment tends to produce a better curative effect than CM [61–64]. This should be the major reason why the RCTs failed to evaluate the real efficacy of CM. In this systematic review, three out of the sixteen trials [40, 43, 54] did not report the TCM diagnostic criteria. Two trials [44, 48] reported the TCM diagnostic criteria but without further details. Therefore, further clinical trials should be conducted with clear TCM diagnostic criteria.

In conclusion, there is some encouraging evidence of BBTD for lowering SBP, but the evidence remains weak due to poor methodological quality of including studies. Rigorously designed trials seem to be warranted to confirm the results.

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

X. Xiong, X. Yang, W. Liu, J. Ma, X. Du, P. Wang, F. Chu, and J. Li contributed equally to this paper.

Acknowledgments

The current work was partially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, no. 2003CB517103) and the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (no. 90209011). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause T, Lovibond K, Caulfield M, McCormack T, Williams B, Guideline Development Group Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. British Medical Journal. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4891.d4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen KJ, Hui KK, Lee MS, Xu H. The potential benefit of complementary/alternative medicine in cardiovascular diseases. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:1 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/125029.125029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su DJ, Li LF. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002–2007. Journal of Health Care For the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22:295–309. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawk C, Ndetan H, Evans MW. Potential role of complementary and alternative health care providers in chronic disease prevention and health promotion: an analysis of National Health Interview Survey data. Preventive Medicine. 2012;54:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Chen K. Integrative medicine: the experience from China. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(1):3–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Chen KJ. Integrating traditional medicine with biomedicine towards a patient-centered healthcare system. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(2):83–84. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer CS. Weighing alternative remedies. February, 2012, amednews.com, http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2012/02/20/prsa0220.htm.

- 9.Luiz AB, Cordovil I, Barbosa Filho J, Ferreira ASA. Zangfu zheng (patterns) are associated with clinical manifestations of zang shang (target-organ damage) in arterial hypertension. Chinese Medicine. 2011;6:p. 23. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahas R. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches to blood pressure reduction: an evidence-based review. Canadian Family Physician. 2008;54(11):1529–1533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst E. Complementary/alternative medicine for hypertension: a mini-review. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 2005;123:386–391. doi: 10.1007/s10354-005-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Current situation and perspectives of clinical study in integrative medicine in China. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/268542.268542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Wang PQ, Xiong XJ. Current situation and re-understanding of syndrome and formula syndrome in Chinese medicine. Internal Medicine. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Chen KJ. Making evidence-based decisions in the clinical practice of integrative medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(6):483–485. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen KJ, Xu H. The integration of traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine. European Review. 2003;11(2):225–235. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H, Chen KJ. Complementary and alternative medicine: is it possible to be mainstream? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2012;18(6):403–404. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MS, Lim HJ, Lee MS. Impact of qigong exercise on self-efficacy and other cognitive perceptual variables in patients with essential hypertension. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(4):675–680. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MS, Lee MS, Choi ES, Chung HT. Effects of Qigong on blood pressure, blood pressure determinants and ventilatory function in middle-aged patients with essential hypertension. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2003;31(3):489–497. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X03001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee MS, Pittler MH, Taylor-Piliae RE, Ernst E. Tai chi for cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: a systematic review. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(9):1974–1975. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32828cc8cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JI, Choi JY, Lee H, Lee MS, Ernst E. Moxibustion for hypertension: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2010;10, article 33 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MS, Choi TY, Shin BC, Kim JI, Nam SS. Cupping for hypertension: a systematic review. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2010;32(7):423–425. doi: 10.3109/10641961003667955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MS, Pittler MH, Guo R, Ernst E. Qigong for hypertension: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(8):1525–1532. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328092ee18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MS, Lee EN, Kim JI, Ernst E. Tai chi for lowering resting blood pressure in the elderly: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2010;16(4):818–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Yao KW, Yang XC, et al. Chinese patent medicine liu wei di huang wan combined with antihypertensive drugs, a new integrative medicine therapy, for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/714805.714805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Control strategy on hypertension in Chinese medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/284847.284847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong GW, Chen MJ, Luo YH, et al. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine for calming Gan and suppressing hyperactive yang on arterial elasticity function and circadian rhythm of blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(6):414–420. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0761-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Liu LT, Zhao WM, et al. Effect of traditional and integrative regimens on quality of life and early renal impairment in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(3):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0216-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macklin EA, Wayne PM, Kalish LA, et al. Stop Hypertension with the Acupuncture Research Program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48(5):838–845. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000241090.28070.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Long-term effects of xuezhikang on blood pressure in hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction: data from the Chinese coronary secondary prevention study (CCSPS) Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2010;32(8):491–498. doi: 10.3109/10641961003686427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DD, Sanchez FA, Duran RG, Kanetaka T, Duran WN. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is a molecular vascular target for the Chinese herb Danshen in hypertension. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;292:H2131–H2137. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DD, Pica AM, Durán RG, Durán WN. Acupuncture reduces experimental renovascular hypertension through mechanisms involving nitric oxide synthases. Microcirculation. 2006;13(7):577–585. doi: 10.1080/10739680600885210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng CF, Koona CM, Cheung DWS, et al. The anti-hypertensive effect of Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) and Gegen (Pueraria lobata) formula in rats and its underlying mechanisms of vasorelaxation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137:1366–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren M, Zhang J, Wang B, et al. Qindan-capsule inhibits proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts and collagen synthesis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;129(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Chen Y, He D, et al. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by serum from rats treated orally with Gastrodia and Uncaria decoction, a traditional Chinese formulation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;114(3):458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang JY, Wang XZ, Luo SS, Wang X, Bian K, Yan Y. Effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on the left ventricular hypertrophy of hypertrophied myocardium in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2010;30(10):1061–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XZ, Jiang JY, Luo SS, et al. Effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on the vascular endothelial function of spontaneous hypertensive rats. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2011;31(6):811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang MQ. Effect of modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on 38 cases of elderly patients with hypertension. Shiyong Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Lin Chuang. 2010;10(2):19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu QF, Wen MX, Lan DH. Effects of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on salt sensitivity and blood lipid in hypertensive patients with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome. Fujian Yi Yao Za Zhi. 2007;29(1):146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li YB, Cui M, Yang Y, et al. Similarity of traditional Chinese medicine formula. Zhong Hua Zhong Yi Yao Xue Kan. 2012;30(5):1096–1097. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng MJ. Effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on 30 patients with hypertension. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Yao Xian Dai Yuan Cheng Jiao Yu. 2011;9(14):p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong YW. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction combining western medicine on 60 patients with phlegm-dampness type primary hypertension. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Yao Xian Dai Yuan Cheng Jiao Yu. 2010;8(13):67–68. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen LQ, Yu HF, Wang WZ. Report of hypertension treated with Banxia baizhu tianma decoction and western medicine. Gansu Zhong Yi. 2005;18(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang JT. Effects of modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction and captopril on essential hypertension with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Ji Zhen. 2001;10(6):p. 364. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Che QF, He LJ, Xu JY. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on homocysteine in essential hypertension with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome. Liaoning Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2011;1813-1814(9):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin ZX. Clinical effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on essential hypertension with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome and blood uric acid metabolism. Xin Zhong Yi. 2011;43(11):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen LQ. The effects of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction and Zexie Decoction on bodymass index and depressurization of patient with hypertension type of accumulation of phlegm-damp in TCM. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Ji Zhen. 2007;16(6):650–651. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo XH. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on 48 patients with phlegm-dampness type hypertension. Hebei Zhong Yi. 2009;31(6):870–871. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li BH. Clinical effect of Wen Dan Decoction and Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on 73 patients with hypertension. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xin Nao Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;9(8):p. 910. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo SP, He XP, Lin XM, Zhu H. Effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on 60 patients with phlegm-dampness type primary hypertension. Shanxi Zhong Yi. 2006;27(7):797–798. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou HM. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on hypertension with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome. Beijing Zhong Yi Yao. 2008;27(5):363–365. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu QF, Wen MX, Lan DH. Effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on insulin resistance and blood lipid in hypertensive patients with abundant phlegm-dampness syndrome. Fujian Zhong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2007;17(2):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lei ZY, Lin X. Effect of Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on blood pressure variability of menopausal patients with hypertension. Xian Dai Zhong Xi Yi Ji He Za Zhi. 2009;18(5):499–500. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu YP, Hu ML, Zhang HT, Shen YS. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on middle-aged primary hypertension. Zhong Yi Yao Xin Xi. 2007;24(1):27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang ZZ. Clinical effect of the modified Banxia baizhu tianma decoction on isolated systolic hypertension. Liaoning Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2002;29(1):p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang SX. Clinical effect of treating hypertension from spleen. Zhong Yi Yao Xue Kan. 2005;23(11):p. 2100. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook For Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5. 1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R. Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1998;19(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen KJ. Clinical service of Chinese medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2008;14(3):163–164. doi: 10.1007/s11655-008-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen KJ, Li LZ. Study of traditional Chinese medicine—which is after all the right way? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2005;11(4):241–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02835782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen KJ. Where are we going? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(2):100–101. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson N. Integrative medicine—traditional Chinese medicine, a model? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(1):21–25. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu AP, Chen KJ. Chinese medicine pattern diagnosis could lead to innovation in medical sciences. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(11):811–817. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0891-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu AP, Chen KJ. Integrative medicine in clinical practice: from pattern differentiation in traditional Chinese medicine to disease treatment. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2009;15(2):p. 152. doi: 10.1007/s11655-009-0152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu MY, Chen KJ. Convergence: the tradition and the modern. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2012;18(3):164–165. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]