Abstract

The challenge of understanding the widespread biological roles of animal microRNAs (miRNAs) has prompted the development of genetic and functional genomics technologies for miRNA loss-of-function studies. However, tools for exploring the functions of entire miRNA families are still limited. We developed a method that enables antagonism of miRNA function using seed-targeting 8-mer locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides, termed tiny LNAs. Transfection of tiny LNAs into cells resulted in simultaneous inhibition of miRNAs within families sharing the same seed with concomitant upregulation of direct targets. In addition, systemically delivered, unconjugated tiny LNAs showed uptake in many normal tissues and in breast tumors in mice, coinciding with long-term miRNA silencing. Transcriptional and proteomic profiling suggested that tiny LNAs have negligible off-target effects, not significantly altering the output from mRNAs with perfect tiny LNA complementary sites. Considered together, these data support the utility of tiny LNAs in elucidating the functions of miRNA families in vivo.

miRNAs are ~22-nucleotide non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by mediating translational repression or promoting degradation of their target mRNAs1,2. Animal miRNAs play critical roles in the control of diverse biological processes, including apoptosis, differentiation, cell proliferation and metabolism3. Furthermore, miRNA perturbations are prevalent in and are strongly associated with the development of human diseases, such as viral infections, cancer, cardiovascular and muscle diseases4–6. Most animal miRNAs bind to partially complementary sites located predominantly in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) through Watson-Crick pairing of the miRNA seed region to the seed match site in the target mRNA2. Prediction of targets by identifying conserved seed sites in mammalian 3′ UTRs or by analysis of transcriptional profiles and proteomic data supports the notion that miRNAs may regulate a large fraction of all protein-coding genes7–9.

The challenges of deciphering the widespread roles of animal miRNAs demand the development of robust technologies that enable the determination of the biological functions of individual miRNAs and miRNA families in vivo. The expanding inventory of loss-of-function studies using miRNA gene knockouts has begun to shed light on the functions of animal miRNAs10–16. However, generation of genetic knockouts to study miRNA families is either difficult or nearly insurmountable, depending upon the complexity of the family. The use of highly expressed transgenes with multiple miRNA binding sites, termed miRNA sponges, offers an alternative approach, allowing sequestration of entire miRNA families in cultured cells17. Although miRNA sponges were recently applied to deplete individual miRNAs in transgenic flies18 and in transplanted hematopoietic cells in mice19, the utility of this tool to explore miRNA function in vivo in higher organisms has not yet been assessed.

An alternative approach to miRNA gene knockouts and sponges is to use chemically modified antisense oligonucleotides, termed antimiRs. These act as competitive inhibitors of miRNAs, negating their ability to interact with and repress cellular target mRNAs. A variety of nucleotide modifications, including LNA, 2′-O-methyl (2′-O-Me) and 2′-O-methoxyethyl (2′-MOE) have been used to enhance the binding affinity of antimiRs to their cognate miRNAs. Additionally, phosphorothioate backbone modifications provide high biostability and facilitate delivery of antimiRs to the liver20–22. The use of 3′ cholesterol-conjugated, 2′-O-Me oligonucleotides with a partial phosphorothioate backbone represents another approach to silence miRNAs in vivo23. Successful inhibition of individual miRNAs using antimiR oligonucleotides has been described in vitro and in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, mice, African green monkeys and hepatitis C virus–infected chimpanzees20–29. However, no study thus far has addressed the functions of co-expressed miRNA family members, which requires a strategy able to simultaneously inhibit the activity of entire miRNA families.

Here we describe an approach that enables miRNA antagonism using fully LNA-modified phosphorothioate oligonucleotides, termed tiny LNAs, complementary to the miRNA seed region. We demonstrate the utility of unconjugated tiny LNAs in inhibiting single miRNAs and entire miRNA families in cultured cells in several tissues of adult mice and in a mouse breast tumor model in vivo. Our study validates the use of tiny LNA–based knockdown in exploring miRNA function, with important implications for the development of therapeutics targeting disease-associated miRNAs.

ONLINE METHODS

Oligonucleotides

The LNA oligonucleotides were synthesized with a phosphorothioate backbone, and their duplex melting temperatures were determined as described21 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

AntimiR oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| antimiR-21 | GATAAGCT | 65 |

| antimiR-122 | CACACTCC | 78 |

| antimiR-155 | TAGCATTA | 61 |

| antimiR-221/222 | ATGTAGC | 56 |

| antilet-7 | ACTACCTC | 75 |

| 2′-O-Me antimiR-21 | gauaagcu | 37 |

| LNA mismatch | GGTAAACT | 39 |

| LNA scramble | TCATACTA | <30 |

LNA nucleotides are shown in uppercase and 2′-O-methyl–modified nucleotides are shown in lowercase. The LNA mismatch control had two mismatches (underlined) to the miR-21 seed region. We measured the Tm values of the LNA control oligonucleotides for the miR-21-LNA mismatch and the miR-21-LNA scramble duplexes.

Cell culture and luciferase reporter assays

Cells were cultured as described in the Supplementary Note. The miRNA reporters were generated by cloning annealed 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotides corresponding to single perfect-match target sites for mouse miR-155 and human miR-21, miR-17, miR-18, miR-19, miR-221 and miR-222 into the 3′ UTR of the Renilla luciferase gene in the dual-luciferase psiCHECK2 plasmid (Promega) (XhoI/NotI sites) (Supplementary Table 4). The 3′ UTRs of AldoA and HMGA2 genes were cloned into the 3′ UTR of the Renilla luciferase gene (XhoI/NotI sites) in the dual-luciferase psiCHECK2 plasmid (Promega) using the PCR primers described in Supplementary Table 5. Transfections and luciferase activity measurements were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Lipofectamine-2000 and Promega Dual-luciferase kits). The pre-miRs were from Ambion. For in vivo studies, a 1.2-kb PCR fragment corresponding to the Firefly luciferase gene was amplified from pGL3 vector (Promega) and subsequently cloned into BglII and XhoI sites of a modified MSCV vector (Clontech), where the hygromycin resistance gene was replaced by the RFP gene. For luciferase control primers and miR-21 luciferase reporter primers, see Supplementary Table 5. The 4T1 cells were infected with virus supernatant and RFP-positive clones were sorted by flow cytometry.

Immunoprecipitation of Ago2 and detection of antimiR-21 in the Ago2 complex

HeLa cells were transfected with 50 nM antimiR-21 and grown for 48 h. The Ago2 protein complex was immunoprecipitated as described47. The Ago2-bound RNA was isolated, electrophoresed in 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to Hybond NX membrane (Amersham) at 20 V for 45 min and cross-linked with EDC reagent at 50–60 °C for 2 h. The LNA-modified oligonucleotide probe (10 pmol) complementary to the 8-mer antimiR-21 was end-labeled at 37 °C for 60 min using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and γ[32P]ATP (Amersham) and purified on a Quick Spin Column (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cross-linked membrane was pre-hybridized for 30 min at 35 °C in hybridization buffer followed by addition of pre-heated probe (1 min at 95 °C) and hybridization for 2 h at 50 °C. Membranes were washed twice in 2×SSC, 0.1% SDS at 50 °C for 10 min and scanned using a Storm 860 scanner (Molecular Dynamics).

Subcellular localization of antimiR-21 in HEK293 cells

HEK293 cells stably expressing the FLAG-tagged Ago2 protein were incubated with 5 µM FAM-labeled antimiR-21 for 72 h followed by staining as described48 using the following antibodies: FLAG antibody (M2, Sigma-Aldrich) or IgG antibody of the same isotype at 1:500 and Alexa 594–labeled goat mouse antibody (Molecular Probes) at 1:500. The cells were mounted using VECTASHIELD containing DAPI and analyzed using a 60× oil immersion objective on an Olympus IX81 confocal microscope with the merge image compiled using the ImageJ program.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from cells and mouse tissues using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). mRNA quantification was done using TaqMan assays and an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems).

RNA blot analysis

Total RNAs (15–20 µg per sample) were electrophoresed in 20% TBE acrylamide gels (Invitrogen) using Hi-Density TBE sample buffer (Invitrogen) without pre-heating, transferred to GeneScreen Plus Membranes (PerkinElmer) and hybridized at 45 °C with dual FAM-labeled LNA probes (Exiqon) as described21. Synthetic miR-21 or miR-122 oligonucleotides and preannealed miR-21– and miR122–antimiR heteroduplexes were used as controls. The blots were scanned using a Storm 860 scanner (Molecular Dynamics).

Protein blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from cultured cells and mouse tissues and subjected to protein blot analysis as described25. The primary antibodies (Supplementary Note) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Soft agar assays

PC3 (2.5 × 103) or HepG2 cells (2.0 × 103) were seeded on 0.35% soft agar plates 24 h after transfection with antimiR-21, incubated at 37 °C for 12 days and stained with 0.005% crystal violet, followed by colony counting.

In vivo experiments

Female NMRI mice (Taconic) were dosed intravenously for three consecutive days with saline-formulated (0.9% NaCl) antimiR-21, antilet-7 or LNA scramble control compound, receiving daily doses of 10 mg/kg and were then killed 48 h after the last dose. For the antimiR-21 time-course study, NMRI mice were dosed with a single intravenous injection of 25 mg/kg and killed at different time points. For miR-122 antagonism, female C57BL/6 mice (Taconic) received three intravenous doses of 5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg of saline-formulated tiny or 15-mer antimiR-122 over 7 days and were killed at day 7.

The 4T1 cells (5 × 104) expressing either Luc control or Luc-21 were injected into the fourth and/or ninth mammary gland of 8–10-week-old Balb/C female mice under isoflurane anaesthesia. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with three daily doses of 10 mg/kg antimiR-21 or LNA scramble control starting at day 10 following transplantation. For in vivo imaging of luciferase activity, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 mg/kg D-Luciferin (Caliper LifeSciences), anaesthetized with isoflurane and imaged 10 min post luciferin injection. In vivo luciferase activity was measured using an IVIS100 imaging system (Caliper LifeSciences).

Biodistribution

The antimiR-21 oligonucleotide was 35S-labeled as described49. Nine female C57BL/6 mice were given a single intravenous dose of 10 mg/kg of saline-formulated 35S-antimiR-21 (specific activity 75.7 µCi/mg). Individual mice were killed at different time points ranging from 5 min to 21 days after administration, immediately frozen at −80 °C and sectioned sagittally for quantitative whole-body autoradiography49.

Human serum albumin binding assay

Human serum albumin (Sigma) was dissolved in PBS (Sigma), filtered on YM-30 columns (Microcon) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with 5′ FAM-labeled antimiR-122 oligonucleotides, synthesized with a complete phosphorothioate or with an unmodified phosphodiester backbone. The samples were centrifuged at 1,500g in YM-30 columns, diluted with distilled water and dispensed for fluorescence measurements using a FLUOstar Optima Microplate Reader.

Cholesterol and transaminase measurements

Total cholesterol, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured as described24.

Microarray expression profiling, proteomics and miRNA target site analyses

Total RNAs were labeled using Whole Transcript Sense Target Labeling Assay (Affymetrix) and hybridized to MoGene 1.0 ST or HuGene 1.0 ST arrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Pre-processing of the microarray data was done using the Variance Stabilization and Normalization (VSN) method for background correction, between-array normalization and transformation, and summarization was done using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) method. The low-level analysis was done using Chip Definition Files where probes were reorganized into Ensembl gene-specific probe set50. In each experiment, we included a filtering step to remove genes that had low absolute expression values and were therefore not likely to be expressed in the tissue under study. The analysis was limited to probe sets exceeding the overall median intensity for at least half of the replicates in a single group.

PC3 cells (6 × 106) were seeded, transfected with 25 nM antilet-7 or LNA control and harvested 48 h post transfection. Washed cell pellets were lysed in 8 M urea, 50 mM Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB, pH 8.5) 0.05% w/v ProteaseMax containing phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor cocktails, pelleted at 14,000g and the soluble protein concentrations were determined. Proteins were extracted from mouse liver samples as described25. Aliquots of 100 µg total protein from each sample were reduced, alkylated and precipitated51. Following re-suspension, samples were digested with Trypsin (1:50 w/w) overnight at 37 °C. The solution volumes were reduced to a final volume of ~20 µl, and labeling with iTRAQ was performed essentially as described51. After labeling, the solutions were combined and desalted with C18 Sep-Pak cartridges. Bound peptides were eluted, reconstituted in OFFGEL sampling buffer and subjected to high resolution fractionation using a reduced glycerol protocol52. Each of the 24 fractions was then analyzed by capillary liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using a protocol modified from reference 53. Mass spectrometry acquisition parameters were adapted from reference 54, with the top four most intense ions selected for consecutive collision induced dissociation (CID) and high energy collisional dissociation (HCD).

Protein identification and quantification was carried out with Mascot 2.3 (Matrix Science) against the human IPI database (87,040 sequences). Methylthiolation of cysteine, N-terminal and lysine iTRAQ modifications were set as fixed modifications, methionine oxidation as variable and one missed cleavage was allowed. iTRAQ ratios were calculated as intensity weighted, using only peptides with expectation values <0.05. Global ratio normalization was performed using intensity summation with no outlier rejection. A more detailed description of the proteomics protocols is given in the Supplementary Note.

Sequence information was downloaded from Ensembl (build 56) and in the case of one-to-many mapping between Ensembl genes and sequence information, the longest sequence was chosen. MicroRNA targets were predicted by searching for canonical seed match sites in the 3′ UTR sequences. Sylamer analysis was carried out as described in reference 40 using spliced complementary DNA sequence information from Ensembl version 59.

RESULTS

Design of miRNA seed-targeting tiny LNAs

Our goal was to develop an antimiR approach that would enable inhibition of miRNA families by targeting their shared seed region (Fig. 1). We have previously reported efficient silencing of the liver-specific miR-122 in rodents and primates using a high-affinity 15-mer LNA-modified antimiR24,26. Here we hypothesized that 8-mer antimiRs complementary to the miRNA seed could have adequate affinity to attain efficient inhibition when synthesized as fully LNA-substituted phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Indeed, 8-mer tiny LNAs targeting the seed regions of miR-21, miR-122, miR-155 and the miR-17/18/19 and let-7 families all showed high duplex melting temperatures (Tm) ranging from 60 °C to 78 °C (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

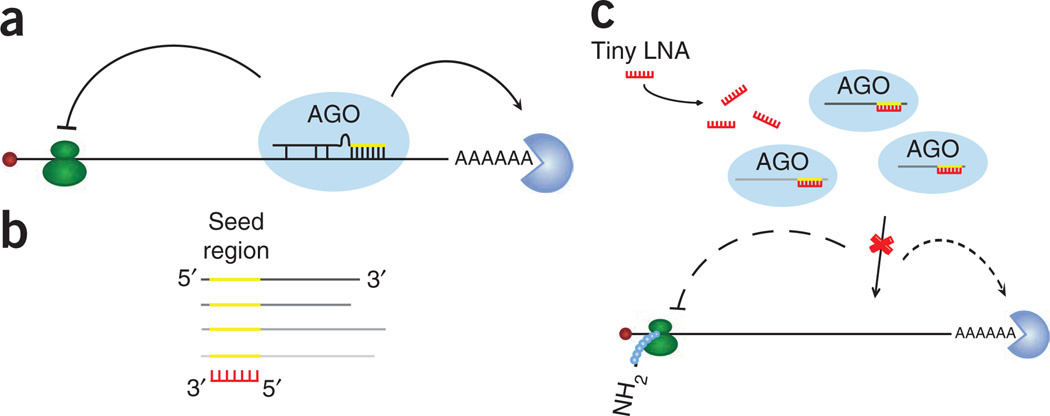

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the miRNA silencing approach using seed-targeting tiny LNAs. (a) miRNAs bind to partially complementary target sites in the 3′ UTRs of target mRNAs and thereby mediate translational repression or mRNA degradation. (b) Tiny LNAs are designed as fully LNA-modified phosphorothioate oligonucleotides complementary to the seed region. (c) The high binding affinity of tiny LNAs enables functional inhibition of co-expressed members of miRNA seed families, which leads to de-repression of target mRNAs.

Inhibition of miR-21 function by an 8-mer tiny LNA

To test our knockdown strategy in cultured cells, we first chose to target miR-21, a potentially oncogenic miRNA that is upregulated and abundant in many solid tumors and in most cancer cell lines30. Thus, a miR-21 luciferase reporter harboring a perfect-match miR-21 target site in its 3′ UTR was repressed in HeLa cells as compared to luciferase controls (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Transfection of the tiny LNA complementary to nucleotides 2–9 in the mature miR-21 sequence resulted in potent antagonism of miR-21, as shown by specific de-repression of the miR-21 reporter with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.9 nM (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). This coincided with sequestration of miR-21 in a slower-migrating heteroduplex with antimiR-21, de-repression of HeLa mRNAs with canonical miR-21 seed match sites and upregulation of the Pdcd4 target protein31 (Fig. 2c–e). Moreover, tiny LNA–transfected PC3 and HepG2 cells formed significantly fewer colonies on soft agar compared to LNA control treated cells (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 1c), as reported previously using other antimiR approaches32. Of note, an 8-mer seed-targeting 2′-O-Me–modified oligonucleotide showed no effect on the miR-21 reporter, consistent with its markedly lower Tm of 37 °C (Fig. 2a and Table 1).

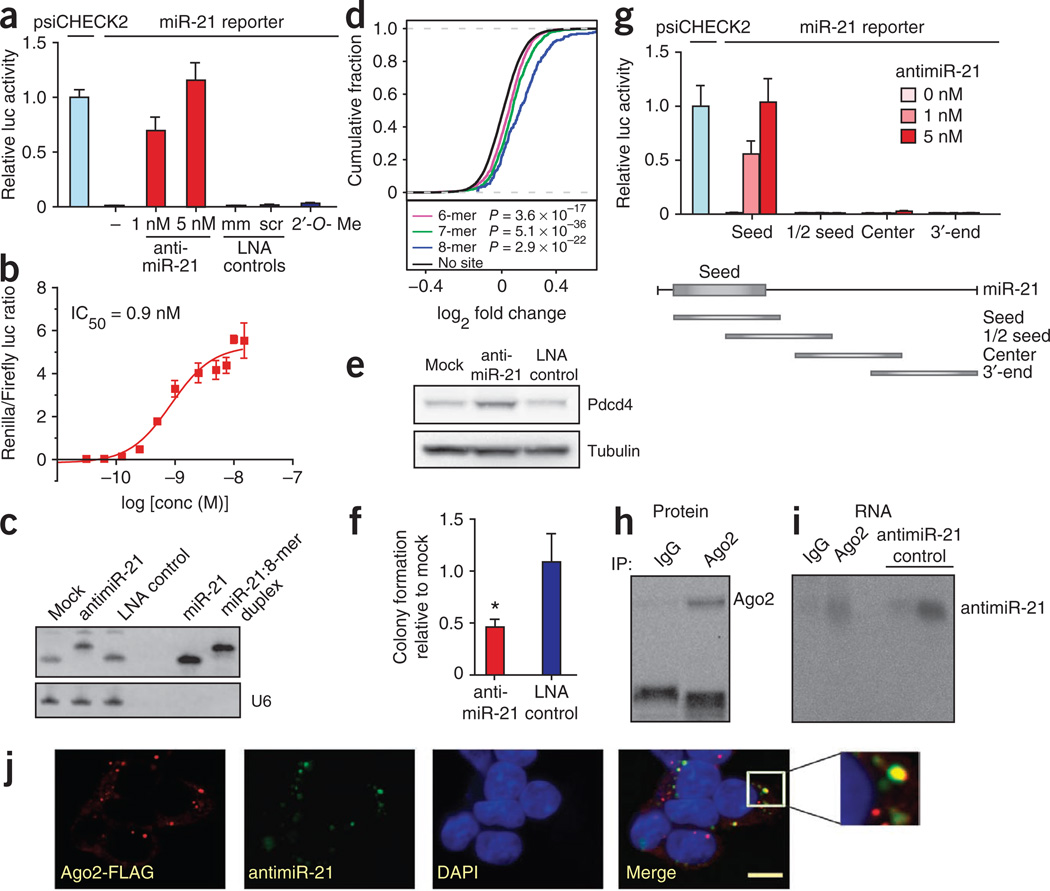

Figure 2.

Inhibition of miR-21 function by tiny antimiR-21. (a) Relative luciferase activity of the miR-21 reporter co-transfected into HeLa cells with tiny antimiR-21, 2′-O-Me antimiR-21, LNA scramble (scr) or mismatch (mm) controls. Error bars, s.e.m. (b) We determined the concentration of antimiR-21 required for half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of miR-21 in HeLa cells using the miR-21 reporter. Error bars, s.e.m. (c) RNA blot analysis of miR-21 in HeLa cells transfected with 5 nM antimiR-21 or LNA scramble control. U6 is shown as a control. (d) De-repression of HeLa mRNAs with canonical miR-21 seed sites after transfection with 5 nM antimiR-21. Cumulative distributions of mRNA changes between antimiR-21–treated and mock-treated cells are shown for each seed site (one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). (e) Protein blot analysis of Pdcd4 expression in HeLa cells (same cells as in c). Tubulin is shown as a control. (f) Colony formation of PC3 cells transfected with antimiR-21 or LNA scramble control. *P < 0.05; n = 3; error bars, s.e.m. (g) Relative luciferase activity of the miR-21 reporter in HeLa cells co-transfected with tiny LNAs targeting the mature miR-21 sequence. Error bars, s.e.m. (h) Protein blot analysis of Ago2 immunoprecipitates from antimiR-21–transfected HeLa cells. IgG was used as a control. (i) RNA blot analysis of RNAs from immunoprecipitated Ago2 samples probed for antimiR-21. The antimiR-21 oligonucleotide (14 pg and 140 pg per sample) was used as a control. (j) Subcellular localization of antimiR-21 in HEK293 cells using immunofluorescence microscopy (red, FLAG-tagged Ago2; green, FAM-labeled antimiR-21; blue, nuclei co-stained with DAPI; scale bar, 10 µm).

To determine whether 8-mer antimiRs must interact with the seed region to inhibit miRNA function, we designed three additional complementary 8-mer LNAs tiled across the mature miR-21 sequence (Fig. 2g). In contrast to the seed-targeting antimiR-21, transfection of tiny LNAs binding adjacent to the seed, to the central region or to the 3′-end of miR-21 had no effect on the miR-21 reporter. We also assessed the specificity and the optimal length of seed-targeting LNAs by introducing one or two adjacent mismatches at all possible nucleotide positions in the antimiR-21 sequence and by shortening the 8-mer LNA to either 7 or 6 nucleotides. The mismatched LNAs, as well as the shorter species, showed substantially reduced potency, consistent with their lower duplex melting temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, we observed lower potencies for extended 9- to 12-mer LNAs, suggesting that fully LNA-modified antimiRs longer than 8 nucleotides might be structurally too rigid to allow effective binding to the miRNA in competition with the target mRNAs.

Next, we investigated whether the tiny antimiR-21 is associated with Argonaute2 (Ago2) protein complexes. To this end, we carried out Ago2 immunoprecipitations in antimiR-21–transfected HeLa cell lysates (Fig. 2h) followed by RNA blot analysis of the Ago2-bound RNAs. Hybridization of the RNA blot with a complementary LNA probe showed presence of the antimiR-21 in the Ago2 complex, but not in the IgG control (Fig. 2i). To determine the subcellular localization, we delivered a FAM-labeled antimiR-21 by unassisted uptake33 to HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-tagged Ago2. Immunofluorescence microscopy of fixed HEK293 cells revealed a punctuated distribution for the FAM-labeled antimiR-21 and for the Ago2 protein, predominantly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. 3), where some of the fluorescent antimiR-21 foci co-localized with Ago2 (Fig. 2j). Together, these findings support the notion that tiny LNAs target Ago2-bound mature miRNAs.

Silencing of miRNA families in cultured cells by tiny LNAs

To further explore knockdown of individual miRNAs, we designed 8-mer antimiRs complementary to the seed regions of miR-122 and miR-155 (Fig. 3a,b and Table 1). We assessed the potency of the tiny antimiR-122 by cloning the 3′ UTR of the AldoA21 target downstream of the Renilla luciferase gene. The activity of this reporter was repressed by a pre–miR-122 in HeLa cells, whereas co-transfection of the antimiR-122 resulted in concentration-dependent de-repression of the AldoA 3′ UTR reporter and upregulation of aldolase A as compared to the antimiR-155 and LNA scramble controls (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). To test the potency of antimiR-155, we constructed a reporter harboring a perfect-match miR-155 target site in the 3′ UTR of Renilla luciferase. This reporter was effectively repressed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated mouse RAW264.7 macrophages, which express elevated levels of miR-155 (ref. 25). Co-transfection of antimiR-155 into RAW264.7 cells de-repressed the miR-155 reporter in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas tiny antimiR-122 and LNA control showed no effect (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4). This antimiR was also able to block repression of the miR-155 target PU.1 (ref. 25) by transfected pre–miR-155 (Fig. 3b).

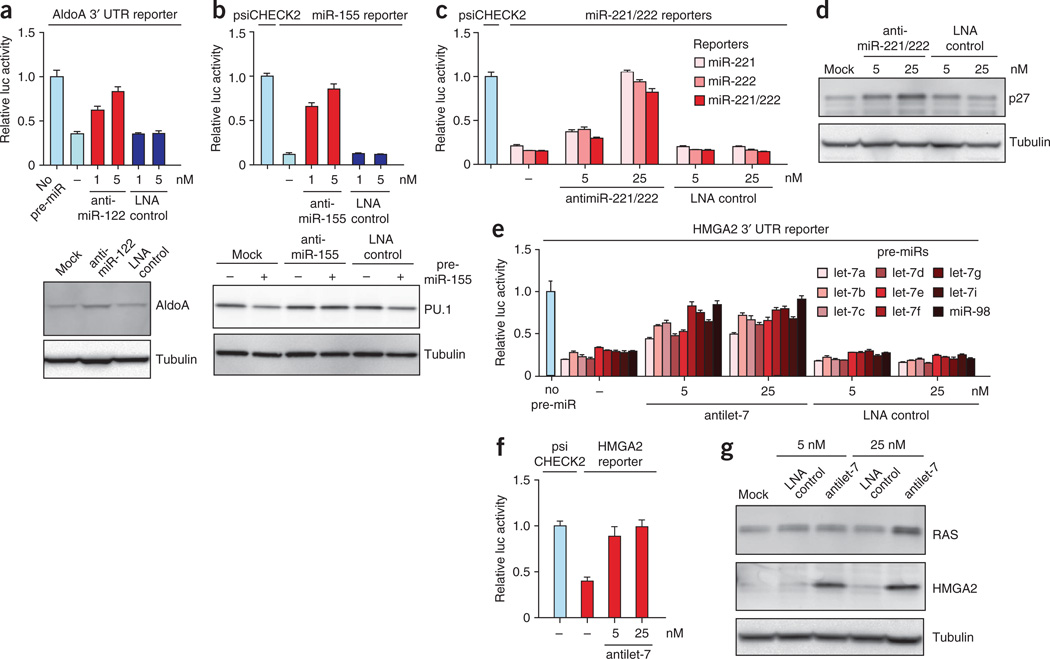

Figure 3.

Silencing of miRNA families by seed-targeting tiny LNAs in cultured cells. (a) Relative luciferase activity of the AldoA 3′ UTR reporter co-transfected into HeLa cells with pre–miR-122 and tiny antimiR-122 or LNA scramble control. Error bars, s.e.m. Protein blot analysis of AldoA expression in HeLa cells transfected with 5 nM antimiR-122 or LNA scramble control. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. (b) Relative luciferase activity of the miR-155 reporter co-transfected into LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells with tiny antimiR-155 or LNA scramble control. Error bars, s.e.m. Protein blot analysis of PU.1 expression in RAW264.7 cells co-transfected with pre-miR-155 and 5 nM tiny antimiR-155 or LNA scramble control. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. (c) Relative luciferase activity of the miR-221 and miR-222 reporters co-transfected into PC3 cells with tiny antimiR or LNA scramble control. Error bars, s.e.m. (d) Protein blot analysis of p27 expression in PC3 cells transfected with tiny antimiR or LNA scramble control. Tubulin is shown as a loading control. (e) Relative luciferase activity of the HMGA2 3′ UTR reporter co-transfected into Huh-7 cells with 10 nM pre–let-7a, -7b, -7c, -7d, -7e, -7f, -7g, -7i or miR-98 and tiny antilet-7 or LNA scramble control. Error bars, s.e.m. (f) Relative luciferase activity of the HMGA2 3′ UTR reporter co-transfected into HeLa cells with tiny antilet-7. Error bars, s.e.m. (g) Protein blot analysis of HMGA2 and RAS expression in HeLa cells transfected with tiny antilet-7 or LNA scramble control. Tubulin is shown as a loading control.

We next tested whether the tiny LNA approach could be used to inhibit simultaneously the activity of miRNAs within the same family. The miR-221/222 family consists of two members that negatively regulate the cell-cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 through two target sites in its 3′ UTR34,35. We synthesized a 7-nucleotide LNA complementary to the miR-221/222 seed region and constructed two reporters with perfect-match target sites for miR-221 and miR-222 in the 3′ UTR of Renilla luciferase. Both reporters were effectively repressed in PC3 cells (Fig. 3c) in accordance with the high expression of miR-221 and miR-222 in this cancer cell line35. In contrast, co-transfection of the tiny antimiR into PC3 cells led to concentration-dependent de-repression of both reporters when assayed either individually or in combination, implying that this tiny LNA is able to inhibit both members of the miR-221/222 family. This is supported by a coincident, concentration-dependent upregulation of p27Kip1 (Fig. 3d). Similarly, transfection of tiny LNAs targeting the seed region of the miR-17, miR-18 and miR-19 families resulted in de-repression of their respective luciferase reporters in HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The let-7 family was originally identified in C. elegans36 and comprises nine members in humans37. Expression of the let-7 family is downregulated in a number of tumor types, including non–small-cell lung cancer. In vitro studies have shown that the let-7 miRNAs can restrain cellular proliferation37, which can, in part, be explained by their target mRNAs, including the well-characterized oncogenes RAS (HRAS, KRAS and NRAS)37 and HMGA2 (ref. 38). To assess inhibition of individual let-7 family members by a seed-targeting antilet-7, we obtained pre-miRs representing all nine let-7 members, let-7a, -7b, -7c, -7d, -7e, -7f, -7g, -7i and miR-98, and assayed a cell line panel to identify a context with minimum levels of endogenous let-7. In a screen of 14 different cell lines, the hepatocellular cancer cell line Huh-7 had the lowest expression of let-7 (data not shown). All nine pre-miRs effectively repressed the HMGA2 3′ UTR reporter in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 3e). By comparison, co-transfection of antilet-7 alongside each pre–let-7 resulted in concentration-dependent de-repression of the HMGA2 reporter, suggesting that this tiny LNA is capable of inhibiting the entire let-7 family in Huh-7 cells. To test whether anti-let-7 could also inhibit endogenous let-7, we co-transfected it alongside the HMGA2 3′ UTR reporter into HeLa or PC3 cells that express most let-7 family members. This resulted in robust de-repression of the HMGA2 reporter in both cell lines (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 6a) and upregulation of the RAS and HMGA2 targets at the protein level (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Furthermore, transfection of the tiny antilet-7 into PC3 cells resulted in significant de-repression of predicted let-7 target mRNAs with canonical 3′ UTR seed sites (Supplementary Fig. 6c). We thus conclude that tiny seed-targeting LNAs can be used to inhibit the function of individual miRNAs and entire miRNA families in cultured cells.

Delivery and efficacy of tiny LNAs in vivo

To determine whether the high binding affinity of tiny LNAs combined with a complete phosphorothioate backbone could enable delivery and silencing of miRNAs in vivo without additional conjugation or formulation chemistries, we first determined the biodistribution of a radiolabeled tiny LNA after systemic delivery into mice. To this end, we injected nine female mice with single intravenous doses of 10 mg/kg 35S-labeled antimiR-21. Individual mice were killed at different time points ranging from 5 min to 21 days after injection, which was followed by sagittal sectioning for whole body autoradiography (Fig. 4a). All animals showed a broad biodistribution with high levels of radioactivity in the kidney cortex, liver, lymph nodes, bone marrow and spleen, whereas we detected no radioactivity in the brain (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7). We observed a rapid decline of radioactivity in heart blood with terminal elimination half-lives of 8–10 h. We detected radioactivity in the urinary tract and in bile in all mice, suggesting that both were routes of elimination. By comparison, most tissues showed a slow decline of radioactivity with half-lives of 100–600 h (Supplementary Fig. 7 and data not shown).

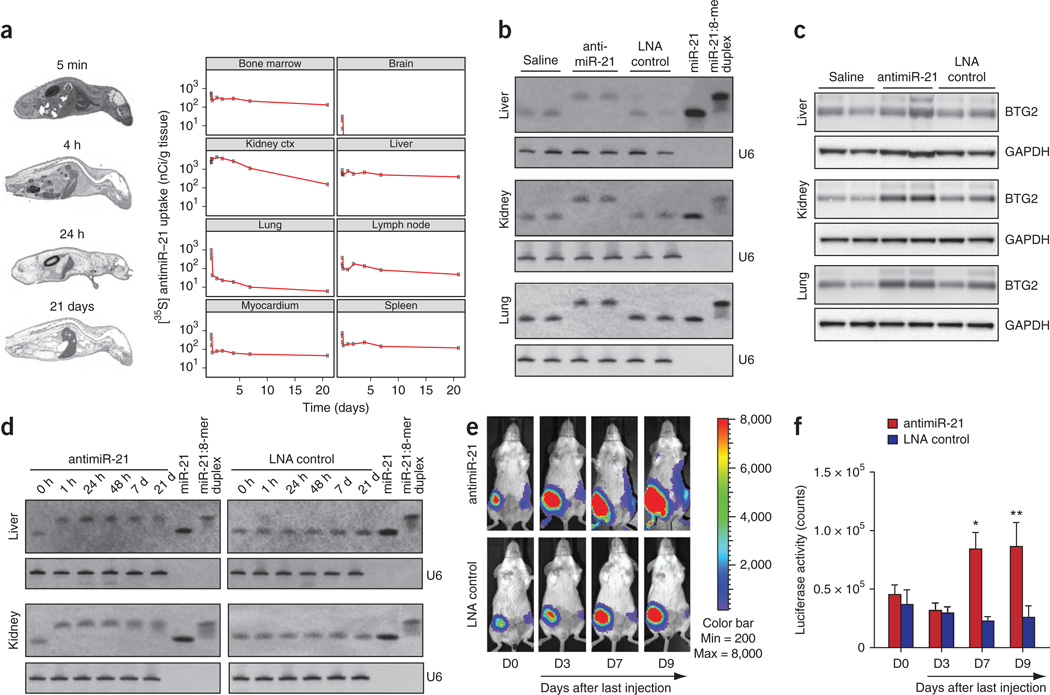

Figure 4.

Silencing of miR-21 in vivo by tiny antimiR-21. (a) Uptake of 35S-labeled antimiR-21 in mice over time after treatment with single intravenous doses of 10 mg/kg. Individual mice were killed at different time points and sectioned sagittally for whole-body autoradiography. Uptake of 35S-labeled antimiR-21 is shown for selected tissues. (b) RNA blot analysis of liver, kidney and lung RNA from mice treated with three intravenous doses of 10 mg/kg tiny antimiR-21 or LNA control or with saline. The RNA blot was probed for miR-21 and U6. (c) Protein blot analysis of BTG2 expression in kidney, liver and lung of mice treated with three intravenous doses of 10 mg/kg tiny antimiR-21 or LNA scramble control or with saline. (d) RNA blot analysis of liver and kidney RNA from mice killed at different time points after treatment with single intravenous doses of 25 mg/kg antimiR-21 or LNA scramble control. The RNA blot was probed for miR-21 and U6. (e) Representative images of miR-21 luciferase reporter de-repression in breast tumor (right side tumors) after treatment with antimiR-21 (upper panel) or LNA control (lower panel). Left side tumors express luciferase alone. We carried out imaging before first injection (D0) and at 3, 7 and 9 days (D3, D7 and D9) after the last injection. (f) In vivo image analysis quantification of two independent experiments. Luciferase activity was normalized to tumor size. *P < 0.05, n = 7 for antimiR-treated group and n = 5 for LNA control; **P < 0.01, n = 5 for both groups. Error bars, s.e.m.

We next assessed in vivo silencing of miR-21 by injecting mice intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg of saline-formulated antimiR-21 on three consecutive days. RNA blot analysis of kidney, liver and lung RNAs showed sequestration of miR-21 in a heteroduplex with the antimiR-21 (Fig. 4b), coinciding with upregulation of the miR-21 target BTG2 (ref. 32) in the same tissues (Fig. 4c). Moreover, sequestration of miR-21 by antimiR-21 was already observed after 1 h and was still effective after 21 days in the kidney and liver of mice injected with a single dose of 25 mg/kg (Fig. 4d). Together, these data imply that systemically delivered, unconjugated tiny LNAs are taken up by a broad range of tissues which, in turn, leads to long-lasting silencing of miRNA function in these tissues in vivo.

Targeting of miR-21 in a mouse breast tumor model

To determine whether tiny LNAs could be used to target miRNAs in solid tumors in vivo, we tested delivery of the antimiR-21 compound in a mouse orthotopic breast tumor model. Young Balb/c female mice were injected with 4T1 cells, a mouse mammary tumor cell line used to model stage IV human adenocarcinoma39. We injected 4T1 cells expressing a miR-21 luciferase reporter into the fourth gland and cells expressing a control luciferase reporter into the ninth gland. Tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg antimiR-21 or LNA control on three consecutive days starting at day 10 after tumor initiation. We obtained in vivo images before treatment and at 3, 7 and 9 days after the last dose. There was significant de-repression of the miR-21 luciferase reporter in tumors of antimiR-21–treated mice, indicating successful delivery to the tumor site (Fig. 4e, upper panel, right-side tumors and Fig. 4f). In contrast, we detected minimal or no alteration of the miR-21 reporter activity in the LNA-control–treated mice (Fig. 4e, lower panel, right-side tumors). We observed no obvious changes in the activity of the luciferase control tumors or of tumor size in either treatment group. The effect of antimiR-21 mediated de-repression of the miR-21 reporter was sustained for 9 days after last injection (D9 in Fig. 4f), with the reporter still being de-repressed in most tumors at day 11 (Supplementary Fig. 8a) followed by a return to basal luciferase activity at day 14 (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c).

To assess the effect of antimiR-21 treatment on tumor growth, we injected Balb/c mice with 4T1 cells as above and then treated them with six injections of 30 mg/kg of antimiR-21 or LNA control after tumor initiation. We evaluated tumor size twice weekly, starting one week after the initial treatment. Mice from the antimiR-21–treated group (n = 10, two tumors per mouse) showed no difference in tumor growth as compared to the LNA controls (n = 8, two tumors per mouse). Thus, in the context of 4T1 cells, an invasive breast tumor cell line, knockdown of miR-21 was not sufficient to impair tumor development. Nevertheless, our results show that the antimiR-21 compound can be delivered to solid tumors, suggesting that tiny LNAs targeting cancer-associated miRNAs could be useful for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Silencing of miR-122 in the mouse liver by tiny LNA

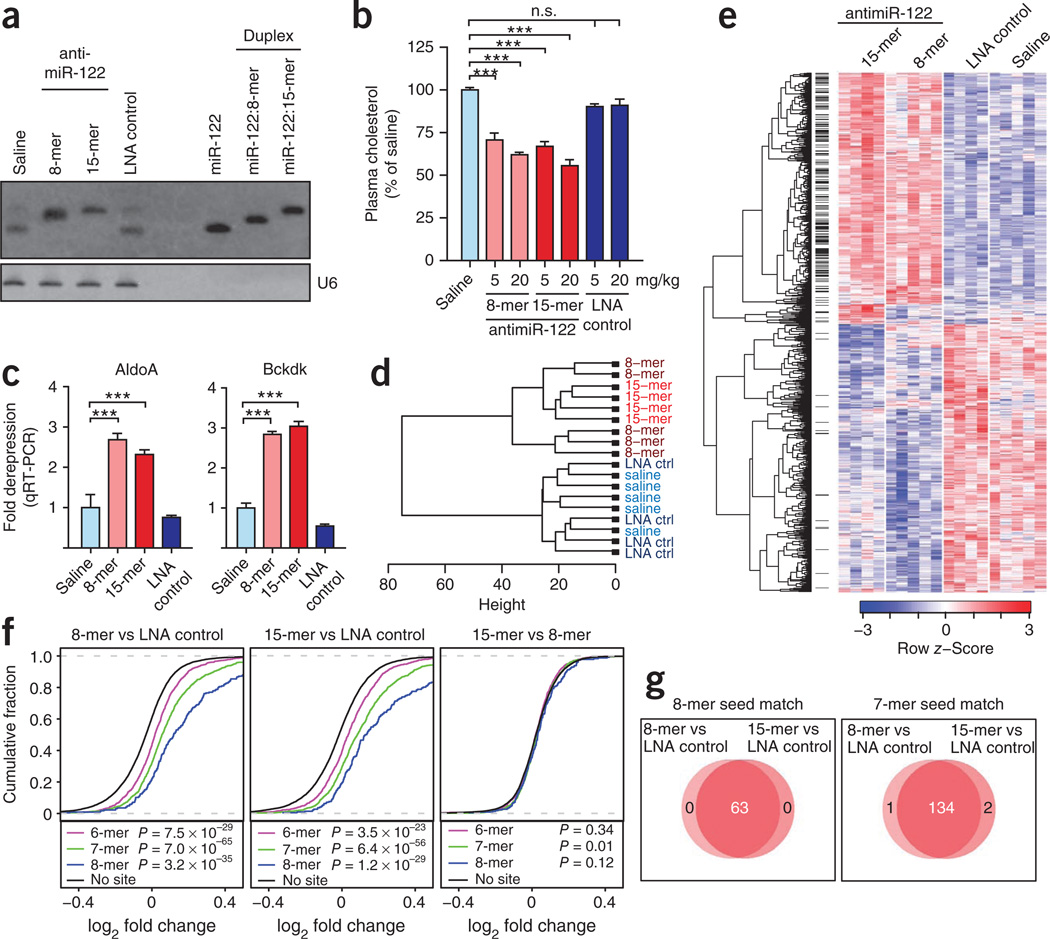

We have previously shown that silencing of the liver-specific miR-122 using a 15-mer LNA-antimiR leads to long-lasting decrease of serum cholesterol in rodents and primates24. Because miR-122 was functionally inhibited by seed-targeting antimiR-122 in cultured cells, we decided to compare the 8-mer and 15-mer antimiRs side-by-side in vivo. We injected mice intravenously with three doses of 5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg and killed them on day 7. RNA blot analysis showed sequestration of miR-122 in a slower-migrating hetero-duplex with both antimiRs. Concomitantly, we observed a dose-dependent lowering of total cholesterol without any hepatotoxicity (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 9) and significant de-repression of the miR-122 targets AldoA and Bckdk21 in the antimiR-122–treated mice (Fig. 5c). In contrast, treatment with an 8-mer antimiR-122 synthesized with a phosphodiester backbone had no effect on miR-122, AldoA, Bckdk or serum cholesterol levels, coinciding with its markedly reduced binding to human serum albumin (Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings highlight the importance of phosphorothioate backbone modifications in facilitating delivery of tiny LNAs in vivo. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of liver mRNA profiles from the treated mice clustered into two distinct branches (Fig. 5d). All controls grouped into a highly compact cluster, suggesting that the 8-mer LNA control has a minimal effect on liver gene expression. By comparison, the expression profiles of the antimiR-treated animals formed a separate uniform cluster, indicating that the two antimiRs have similar effects on the liver transcriptome (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

Silencing of miR-122 in the mouse liver by seed-targeting tiny LNA. (a) RNA blot analysis of liver RNAs from mice after treatment with three intravenous doses of 20 mg/kg tiny antimiR-122, 15-mer antimiR-122 or LNA scramble control or with saline. The RNA blot was probed for miR-122 and U6. (b) Total plasma cholesterol levels in mice treated with three intravenous injections of tiny antimiR-122, 15-mer antimiR-122, LNA scramble control or with saline (error bars, s.e.m.; n = 5; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (c) Quantification of the AldoA and Bckdk mRNAs (same samples as in a, normalized to GAPDH; error bars, s.e.m.; n = 5; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (d) Hierarchical clustering of samples using filtered microarray expression data from mice treated with tiny antimiR-122, 15-mer antimiR-122, LNA scramble control or with saline (same samples as in a; n = 5, except for 15-mer antimiR and LNA scramble control, where n = 4). (e) Hierarchical clustering of genes showing differential expression at a false discovery rate of 1% when comparing antimiR-122 profiles to controls or when comparing the two antimiR-122 profiles directly. Predicted miR-122 targets (7-mer and 8-mer seed match sites) are indicated with black lines between the heatmap and the dendrogram. (f) De-repression of liver mRNAs with canonical miR-122 seed match sites (same samples as in e). We determined the significance of the differences from mRNAs with no sites using one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. (g) Venn diagrams showing the number of liver mRNAs upregulated by antimiRs both with 8-mer or 7-mer seed matches in the 3′ UTRs.

To validate this conclusion, we identified all differentially expressed liver mRNAs by comparing the two antimiR-122 treatment groups to the LNA control and to each other. Cluster analysis showed a high level of concordance between the 15-mer and 8-mer antimiR-122–treated animals, underscored by only 32 differentially expressed transcripts out of the 1,003 mRNAs identified (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, silencing of miR-122 in mice by the two LNAs resulted in significant and highly similar de-repression of predicted miR-122 target mRNAs with canonical 3′ UTR seed match sites (Fig. 5f). Notably, of the liver mRNAs upregulated by both antimiRs, 63 had 8-mer seed sites, whereas 134 mRNAs had 7-mer seed sites in the 3′ UTRs (Fig. 5g). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the downregulated mRNAs in the antimiR-treated mice showed an overrepresentation of GO terms related to lipid and steroid metabolic processes, including cholesterol biosynthesis (data not shown), consistent with lowering of serum cholesterol, as has also been reported previously in rodents and primates20,21,23,24,26. Taken together, these data show that both 15-mer and tiny LNA-antimiRs lead to similar physiological responses in treated animals and to highly comparable effects on miR-122 targets in the mouse liver.

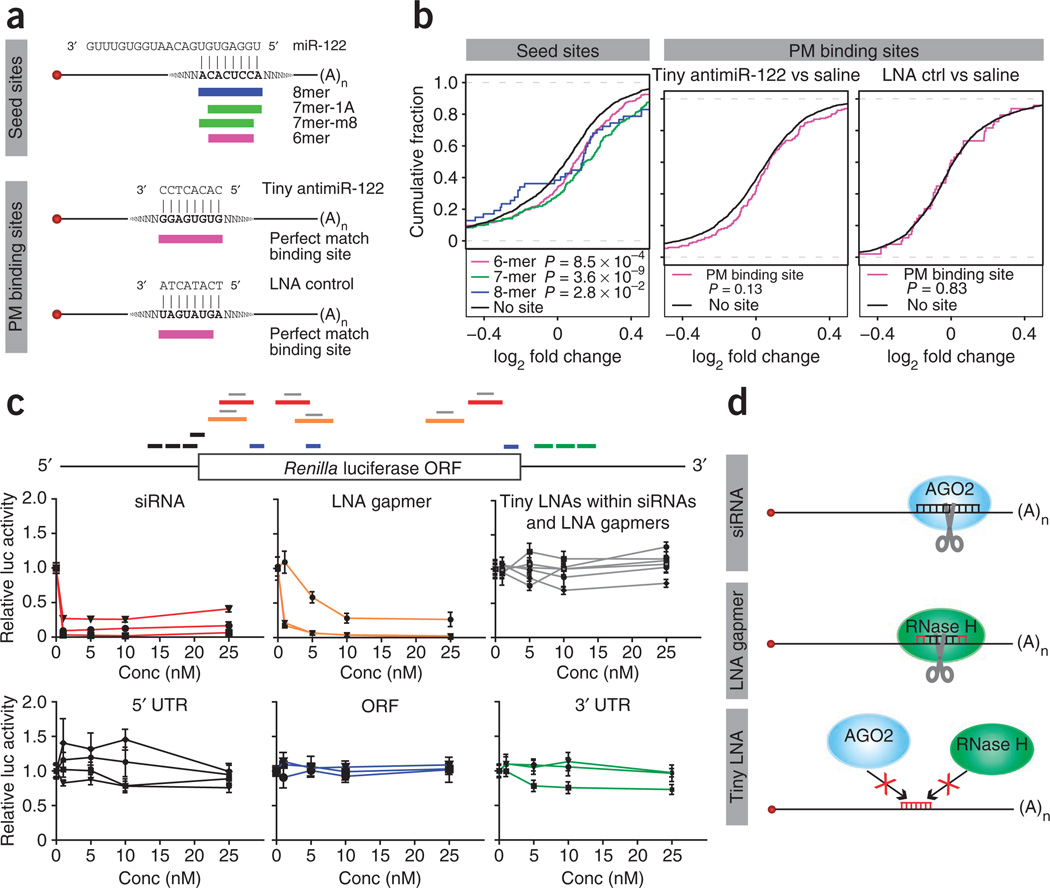

Assessment of off-target effects

Short, 8-mer oligonucleotides have many predicted perfect-match recognition sequences in cellular mRNAs and, thus, we asked whether potential binding of tiny LNAs to such sites could lead to off-target effects at the mRNA or protein level. Sylamer40 analysis of microarray data from cell culture and in vivo experiments with tiny antimiR-21, antilet-7 or antimiR-122 showed significant enrichment of seed-match–containing mRNAs in the most upregulated mRNA pools, consistent with the notion that functional miRNA inhibition leads to de-repression of direct targets (Supplementary Figs. 11,12 and Supplementary Tables 2,3). By comparison, we observed no effect of the tiny LNAs on mRNAs with 6-, 7- or 8-nucleotide perfect-match binding sites, suggesting that mRNAs with such sites are not affected. Next, we assessed the impact of tiny LNAs on protein production by analyzing liver protein samples from mice treated with antimiR-122 and protein extracts from antilet-7–transfected PC3 cells employing iTRAQ (isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation) labeling of peptides combined with liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. This resulted in quantification of 3,772 and 2,402 proteins from the mouse liver and PC3 cells, respectively, of which 3,184 and 1,908 could be mapped uniquely to Ensembl gene IDs. In both data sets, the effect of tiny LNA–mediated miRNA silencing could be detected on the protein output, as shown by significant de-repression of proteins derived from mRNAs with canonical seed-match sites (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Fig. 13). In contrast, none of the tiny LNAs showed a significant shift in levels of proteins encoded by mRNAs with tiny LNA binding sites (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Fig. 13).

Figure 6.

Off-target analysis. (a) Schematic representation of the different seed match sites in miR-122 target mRNAs and the putative perfect-match binding sites of the tiny antimiR-122 and the LNA scramble control, respectively. (b) De-repression of proteins encoded by mRNAs with canonical miR-122 seed match sites after treatment with 3 × 20 mg/kg tiny antimiR-122. The cumulative fraction plots show the distribution of log2 fold changes between the antimiR-122– and LNA-control–treated mice for each seed match type. Proteins encoded by mRNAs with perfect-match binding sites to antimiR-122 or LNA scramble control did not show a significant shift relative to saline control. (c) Relative luciferase activity of a Renilla luciferase reporter co-transfected into HeLa cells with three siRNAs, three LNA gapmers targeting the Renilla ORF (red and orange), three tiny LNAs with binding sites within the siRNA or LNA gapmer target sequences (gray), tiny LNAs binding to the 5′ UTR (black), ORF (blue) or 3′ UTR (green) of Renilla luciferase, respectively. Error bars, s.e.m. (d) Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of siRNAs and LNA gapmers and binding of tiny LNAs to a perfect-match mRNA site.

To further investigate the effect of tiny LNAs on protein levels using a highly sensitive readout, we designed sixteen 8-mer LNAs encompassing the entire Renilla luciferase reporter gene. As expected, co-transfection of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or RNase H-recruiting LNA gapmers targeting Renilla resulted in potent knockdown of the Renilla luciferase reporter (Fig. 6c,d). In contrast, tiny LNAs targeting 8-mer recognition sequences within the siRNA or LNA gapmer target sites showed negligible effects on luciferase activity (Fig. 6c). Similarly, ten additional tiny LNAs binding at perfect-match sites in the 5′ UTR, open reading frame (ORF) or 3′ UTR of Renilla luciferase showed a modest effect at best on luciferase activity (Fig. 6c). In summary, our data suggest that 8-mer tiny LNAs do not significantly affect the protein output from mRNAs with perfect-match binding sites.

DISCUSSION

We developed a method that exploits the high affinity of 7- to 8-mer, fully modified LNA oligonucleotides toward complementary RNA molecules to antagonize miRNA function. When designed to target the miRNA seed, tiny LNAs enable specific and concentration-dependent inhibition of entire miRNA families in cultured cells. Our data highlight the importance of targeting the miRNA seed and suggest that this region is more accessible for inhibition, as additional tiny LNAs tiled across mature miR-21 (Fig. 2g), miR-155 and let-7 sequences (Supplementary Fig. 14) had no or limited effect on miRNA activity. This is consistent with the model in which the miRNA seed region is exposed and preorganized in the Argonaute complex to favor efficient pairing to the seed-match site in the target mRNA2,41,42. In addition, structural studies have shown that the fixed N-type conformation of the LNA nucleoside preorganizes LNA oligonucleotides in a high-affinity conformation for binding complementary RNA sequences, thereby adopting an A-form helix geometry typical for RNA-RNA duplexes43. Thus, the remarkable thermodynamic stability of tiny LNAs described here facilitates their effective binding to miRNA seeds in competition with cellular target mRNAs leading to sequestration of the miRNA. The importance of a high binding affinity of tiny LNAs is further highlighted by the fact that an isosequential 8-mer 2′-O-Me–modified antimiR-21 oligonucleotide with a low Tm of 37 °C showed no inhibition of miR-21 activity.

A key feature of our approach is that it enables simple systemic delivery of unconjugated, saline-formulated tiny LNAs in vivo when combined with a phosphorothioate backbone. As shown here, intravenously injected tiny LNAs are taken up by a range of mouse tissues, which leads to long-lasting silencing of miRNA function. This has important ramifications for functional studies of animal miRNAs in vivo. First, unlike other chemically modified antimiR oligonucleotides, tiny LNAs enable simultaneous knockdown of co-expressed miRNA family members that may have redundant biological functions. Although genetic approaches have been used successfully to generate triple and double knockouts for functional studies of the C. elegans let-7 (ref. 10) and mouse miR-208 families16, respectively, silencing of miRNA seed families using tiny LNAs is less time consuming and less labor intensive than this approach. Furthermore, by using different dosing regimens, tiny LNAs can be used to study the physiological consequences of acute and partial inhibition of miRNA families in vivo, which is technically challenging using genetic knockouts. Second, we found that silencing of the liver-expressed miR-122 in mice by a tiny 8-mer LNA in comparison with a 15-mer antimiR led to highly similar effects in vivo. Notably, of the liver mRNAs de-repressed by both antimiRs, about 200 messages had canonical 8-mer or 7-mer seed matches in the 3′ UTRs. These results suggest that the tiny LNA approach has the potential to pinpoint physiologically relevant miRNA targets in vivo, thereby complementing bioinformatic, proteomic and Ago HITS-CLIP (high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation) approaches for uncovering miRNA-target interactions on a genomic scale8,9,44,45. Moreover, tiny LNAs are also applicable to miRNA-target interaction studies in cultured cells and should be especially useful for identifying common targets shared by co-expressed miRNA family members. Third, apart from efficient miRNA silencing in several mouse tissues, systemically delivered tiny LNAs showed uptake and miR-21 knockdown in a mouse model of breast cancer, thus underscoring the potential of this technology in functional studies of disease-implicated miRNAs in vivo. Given the emerging roles of miRNA seed families in disease, such as the let-7 family in lung cancer37,46, the miR-19 family in Myc-driven B-cell lymphomas15 and the miR-208 family in cardiac remodeling16, we envision tiny LNAs as important tools to study the functional overlap within miRNA seed families in animal disease models. Finally, our data demonstrate in vivo efficacy and the lack of acute toxicities in mice, which imply that tiny LNAs may be well suited to the development of therapeutic strategies aimed at pharmacological inhibition of disease-associated miRNAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank A. Koustrup, H. Brostrøm, A. Konge, J.J. Jørgensen, M. R. Møller, L. Bang and M. Meldgaard for excellent technical assistance, and A. Lund and T. Bou-Kheir for reagents. This study was supported by grants from the Danish National Advanced Technology Foundation and the Danish Medical Research Council to S.K.

Footnotes

Accession codes. The microarray data are deposited in the public data repository ArrayExpress under the following accession codes: E-MEXP-2801 (antilet-7 mediated silencing of let-7 in the mouse liver), E-MEXP-2802 (miR-122 silencing in the mouse liver), E-MEXP-2803, (miR-21 inhibition in HeLa cells) and E-MEXP-2804 (let-7 inhibition in PC3 cells).

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.O., C.O.d.S., A.P., M.H., O.B., C.R., C.F. and E.M.S. performed experiments and contributed data. H.F.H. performed synthesis of oligonucleotides. S.O., C.O.d.S., A.P., M.H., M.L., J.S., T.K., D.P., G.J.H. and S.K. designed experiments and discussed the data. S.K. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript together with S.O. and with input from other authors.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics/.

References

- 1.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottwein E, Cullen BR. Viral and cellular microRNAs as determinants of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AH, Liu N, van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNA control of muscle development and disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventura A, Jacks T. MicroRNAs and cancer: short RNAs go a long way. Cell. 2009;136:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim LP, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baek D, et al. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selbach M, et al. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott AL, et al. The let-7 MicroRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokol NS, Ambros V. Mesodermally expressed Drosophila microRNA-1 is regulated by Twist and is required in muscles during larval growth. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2343–2354. doi: 10.1101/gad.1356105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miska EA, et al. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventura A, et al. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rooij E, et al. Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007;316:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.1139089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu P, et al. Genetic dissection of the miR-17~92 cluster of microRNAs in Myc-induced B-cell lymphomas. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2806–2811. doi: 10.1101/gad.1872909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooij E, et al. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loya CM, Lu CS, Van VD, Fulga TA. Transgenic microRNA inhibition with spatiotemporal specificity in intact organisms. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentner B, et al. Stable knockdown of microRNA in vivo by lentiviral vectors. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:63–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esau C, et al. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmen J, et al. Antagonism of microRNA-122 in mice by systemically administered LNA-antimiR leads to up-regulation of a large set of predicted target mRNAs in the liver. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1153–1162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horwich MD, Zamore PD. Design and delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to block microRNA function in cultured Drosophila and human cells. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1537–1549. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krutzfeldt J, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature. 2005;438:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elmen J, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worm J, et al. Silencing of microRNA-155 in mice during acute inflammatory response leads to derepression of c/ebp Beta and down-regulation of G-CSF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5784–5792. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanford RE, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma L, et al. Therapeutic silencing of miR-10b inhibits metastasis in a mouse mammary tumor model. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:341–347. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson B, et al. Specificity and functionality of microRNA inhibitors. Silence. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng G, Ambros V, Li WH. Inhibiting miRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans using a potent and selective antisense reagent. Silence. 2010;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankel LB, et al. Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1026–1033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu M, et al. Regulation of the cell cycle gene BTG2, by miR-21 in human laryngeal carcinoma. Cell Res. 2009;19:828–837. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein CA, et al. Efficient gene silencing by delivery of locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides, unassisted by transfection reagents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.le Sage C, et al. Regulation of the p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2007;26:3699–3708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galardi S, et al. miR-221 and miR-222 expression affects the proliferation potential of human prostate carcinoma cell lines by targeting p27Kip1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23716–23724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinhart BJ, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson CD, et al. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulaski BA, Clements VK, Pipeling MR, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Immunotherapy with vaccines combining MHC class II/CD80+ tumor cells with interleukin-12 reduces established metastatic disease and stimulates immune effectors and monokine induced by interferon gamma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2000;49:34–45. doi: 10.1007/s002620050024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Dongen S, Abreu-Goodger C, Enright AJ. Detecting microRNA binding and siRNA off-target effects from expression data. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:1023–1025. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Sheng G, Juranek S, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Structure of the guide-strand-containing argonaute silencing complex. Nature. 2008;456:209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature07315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, et al. Structure of an argonaute silencing complex with a seed-containing guide DNA and target RNA duplex. Nature. 2008;456:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nature07666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vester B, Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acid): high-affinity targeting of complementary RNA and DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13233–13241. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimson A, et al. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar MS, et al. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyoshi K, Uejima H, Nagami-Okada T, Siomi H, Siomi MC. In vitro RNA cleavage assay for Argonaute-family proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;442:29–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-191-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broom OJ, Zhang Y, Oldenborg PA, Massoumi R, Sjolander A. CD47 regulates collagen I-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression and intestinal epithelial cell migration. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Straarup EM, et al. Short locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides potently reduce apolipoprotein B mRNA and serum cholesterol in mice and non-human primates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7100–7111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dai M, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross PL, et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horth P, Miller CA, Preckel T, Wenz C. Efficient fractionation and improved protein identification by peptide OFFGEL electrophoresis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:1968–1974. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600037-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor P, et al. Automated 2D peptide separation on a 1D nano-LC-MS system. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:1610–1616. doi: 10.1021/pr800986c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bantscheff M, et al. Robust and sensitive iTRAQ quantification on an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:1702–1713. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800029-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.