Abstract

Syncytin-1 and envPb1 are two conserved envelope genes in the human genome encoded by single loci from the HERV-W and -Pb families, respectively. To characterize the role of these envelope proteins in cell–cell fusion, we have developed lentiviral vectors that express short hairpin RNAs for stable knockdown of syncytin-1 and envPb1. Analysis of heterotypic fusion activity between trophoblast-derived choriocarcinoma BeWo cells, in which syncytin-1 and envPb1 are specifically silenced, and endothelial cells demonstrated that both syncytin-1 and envPb1 are important to fusion. The ability to fuse cells makes syncytin-1 and envPb1 attractive candidate molecules in therapy against cancer. Our available vectors may help eventually to decipher roles for these genes in human health and/or disease.

During mammalian evolution, endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) have invaded the germ-line of the host, and proviral loci occupy ~8 % of the genome according to the draft of the sequence of the human genome (Lander et al., 2001), although the complexity of variation among individuals remains to be clarified (Conrad et al., 2010), and current sequence-assembly software may miss individual repetitive elements. Most of these ancient viral loci are non-functional as the result of the accumulation of debilitating mutations. Excluding young loci of HERV-K origin, only 18 intact viral genes have been annotated among the thousands of proviral loci (Villesen et al., 2004). Interestingly, 15 of these encode viral envelope genes (Villesen et al., 2004). The envelope glycoproteins encoded by syncytin-1 (ERVWE1), syncytin-2 (HERV-FRD) and envPb1 are in fact still fusion-competent and may, at least after ectopic expression, cause formation of multinucleated syncytia in cell cultures (Blaise et al., 2003, 2005; Blond et al., 2000; Mi et al., 2000). Fusion of cells plays an essential role in human development and reproduction, for instance in sperm–oocyte fusion or when macrophages or myoblasts differentiate into syncytia osteoclasts or muscle fibres, respectively. Another important fusion event occurs during formation of the syncytiotrophoblast layer in the placenta. Syncytin-1 and -2 are highly expressed in placental tissue (Blaise et al., 2003; Blond et al., 2000; Mi et al., 2000) and have therefore been proposed to mediate formation of the syncytiotrophoblast layer (Blond et al., 2000; Esnault et al., 2008; Mi et al., 2000; Ruebner et al., 2010). Recent data from our laboratory indicate that syncytin-1 might also be involved in fusion between myoblasts and osteoclasts (Bjerregaard et al., 2011; Søe et al., 2011).

We report here on lentiviral vectors for stable downregulation of human fusion-competent envelope genes. In order to silence the envelope genes syncytin-1 (envW1) and envPb1, we constructed three U6-promoted short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression plasmids for each target gene. The knockdown efficacy of each shRNA was tested in co-transfection assays in HEK 293 cells with psiCheck-based luciferase reporters, in which the Renilla luciferase (Rluc) reporter transcript is fused to the full-length envelope target, while firefly luciferase (Fluc) serves as an internal control (Table 1). We then cloned the two best U6–shRNA cassettes (shW and shPb; Table 1) into a third-generation pHIV7-based lentiviral vector to produce pHIV7-U6-shRNAs vectors that would allow stable transduction of target cells (see Supplementary Methods and Table S1, available in JGV Online). We produced VSV-G-pseudotyped lentiviral particles and concentrated the supernatant by ultracentrifugation to a titre of around 1–2×108 c.f.u. ml−1, as determined by transduction of human HT1080 cells.

Table 1. Knockdown efficiency of U6-promoted shRNA constructs against a luciferase–envelope reporter by transient co-transfection in HEK 293 cells (n = 3).

| pFRT-U6 construct | Target site | Residual Rluc activity (%) |

| shW | Syncytin-1 positions 3–21 | 18±1 |

| shW2 | Syncytin-1 positions 1095–1113 | 96±8 |

| shW3 | Syncytin-1 positions 1520–1538 | 95±17 |

| shPb | envPb1 positions 1202–1220 | 22±2 |

| shPb2 | envPb1 positions 1705–1723 | 24±1 |

| shPb3 | envPb1 positions 1747–1765 | 26±2 |

We transduced trophoblast-derived choriocarcinoma BeWo cells with our envW1- or envPb1-targeting vector using an m.o.i. of 5, and achieved more than 90 % positively transduced BeWo cells, as determined by GFP marker expression. We cultured the cells for 2 weeks to ensure efficient silencing, during which period the cells retained their green fluorescence. We did observe mild growth retardation of shRNA-expressing BeWo cells, independent of shRNA vector context. This is a phenotype often observed with stable shRNA expression, and may, in the worst cases, even induce cytotoxicity and apoptosis (An et al., 2006). We are confident that this minor growth impairment does not influence our data, since neither gene expression levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or env nor fusion assay activity were grossly affected in cells transduced by the ‘empty’ lentiviral vector compared with the non-targeting control shRNA (shS1).

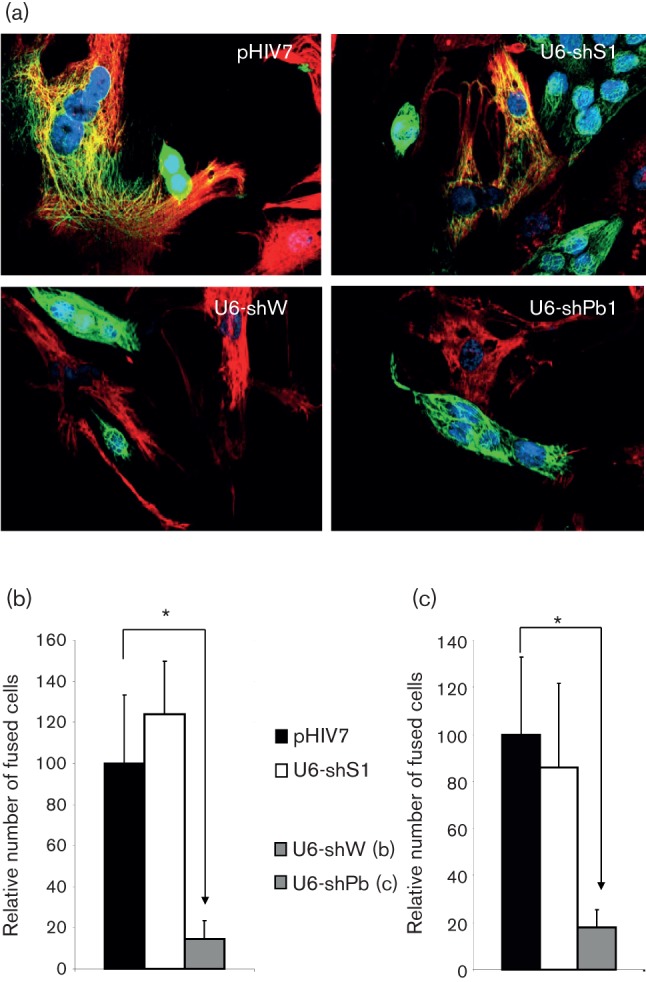

We initially confirmed our stable knockdown strategy by targeting syncytin-1 (envW1) in BeWo cells, since these trophoblast-derived choriocarcinoma cells normally express high levels of syncytin-1. We used a quantitative cell–cell fusion assay in which EnvW1-expressing cells fuse spontaneously to the receptor (ASCT2)-expressing fusion partner (HUV-EC-C; human endothelial cells) (Bjerregaard et al., 2006; Mortensen et al., 2004). Fused cells were visualized and counted using cell-type-specific antibodies, and double-positive cells were scored (Fig. 1a). Using cytokeratin as a marker for BeWo cells and vimentin as an endothelial marker, we found a marked drop (86±9 %; P<0.001) in the fraction of fused BeWo-HUVEC cells upon silencing of envW1 (Fig. 1b). This result verifies the validity of stable silencing of envelope genes to study heterotypic cell–cell fusion. We measured the level of envW1 expression by quantitative RT-PCR and found a significant reduction of envW1 RNA expression, to 49±8 % (relative to GAPDH; P<0.05), in cells expressing envW1-targeting shRNAs compared with control cells transduced with an ‘empty’ pHIV7 vector not expressing any shRNA. EnvPb1 and syncytin-2 expression was unchanged in shW-transduced cells and in control cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Silencing of syncytin-1 and EnvPb1 reduces BeWo-HUVEC cell fusion activity. (a) Representative images from co-culture experiments. BeWo cells were stained with the epithelial marker cytokeratin (Alexa-488; green) and HUVEC cells were stained with the endothelial marker vimentin (Alexa-594; red). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). BeWo cells were transduced with an ‘empty’ lentivirus expressing no siRNA (pHIV7), a irrelevant control siRNA targeting HIV-1 (U6-shS1), a syncytin-1-targeting siRNA (U6-shW) or a envPb1-targeting siRNA (U6-shPb1). (b) Percentages of fused HUVEC cells after co-culture with transduced BeWo cells expressing an shRNA targeting syncytin-1 (means±sd; asterisks indicate P<0.0001). (c) Similar to (b), but with transduced BeWo cells expressing an shRNA targeting envPb1 (means±sd; asterisks indicate P<0.0001).

We next proceeded to silence the recently discovered envelope gene envPb1 (Villesen et al., 2004). Stably transduced (shPb) cells were tested for heterotypic fusion activity when the BeWo–shRNA cells were co-cultured with HUVEC cells (Fig. 1c). We found that, much like syncytin-1-depleted cells, knockdown of envPb1 resulted in a marked reduction (82±2 %; P<0.001) in BeWo–HUVEC heterotypic fusion activity. HERV-Pb1 is integrated in an antisense orientation in the intron of the RIN3 gene. To avoid a contribution from RIN3 intronic RNA, a strand-specific quantitative PCR protocol was established in order to determine mRNA levels for envPb1 (Supplementary Methods). We found that untreated BeWo cells expressed substantial levels of envPb1 RNA and, like Vargas et al. (2012), we noted an increase (~7-fold) upon treatment with 50 nM forskolin. When examining the endogenous levels of envPb1 expression in BeWo cells transduced with our lentiviral vector harbouring the U6–shPb silencing cassette, we found a potent downregulation to less than 5 % (P<0.05), whereas there was no effect on RNA for envW1 or syncytin-2. This indicates that the strong reduction in cell fusion in cells transduced by the U6–shPb vector is in fact due to a reduction in envPb1 expression.

EnvPb1 is capable of mediating cell–cell fusion upon ectopic expression in a number of cell lines (Blaise et al., 2005), and our results imply that HUVEC cells also express the cognate receptor for EnvPb1. In the light of the fact that BeWo is a choriocarcinoma-derived cell line, this adds credence to the notion that fusion in cancer cells may exploit endogenous envelope proteins as a cell–cell fusion device (Bjerregaard et al., 2006, 2011; Søe et al., 2011). Recently, data have accumulated to indicate that fusion in general may be involved in cancer development using envelope proteins as well as other unrelated cellular fusion machineries (Larsson, 2011). Our findings suggest that both syncytin-1 and envPb1 may direct heterotypic fusion of choriocarcinoma cells and endothelial cells, a finding with possible relevance for syncytial tumours or placenta-derived cancers. Strikingly, we observed a strong reduction in fusion by knockdown of expression of either envelope gene. This may suggest that they cannot simply compensate for each other and/or that there is no simple linear relationship between envelope mRNA and fusion activity. In fact, the regulation of cell–cell fusion mediated by env genes may be quite complex and involve multiple envelope proteins, potentially in heteromeric complexes. While it is well established that the fusion activity of envelope proteins of exogenous gammaretroviruses is strictly regulated by proteolytic cleavage of their C terminus after budding, the steps that lead to the physiological activation of the cell–cell fusion activity of endogenous envelope proteins are less clear.

Evolutionary conservation suggests that the envPb1 gene was preserved for a physiological purpose. The open reading frame has remained intact for ~30 million years, and there is strong evidence for purifying selection among hominoids and Old World monkeys (Aagaard et al., 2005). Whether envPb1 was co-opted to be fusogenic, to protect against incoming viruses or to perform other, perhaps immunological, roles has yet to be answered (Prudhomme et al., 2005). The involvement of multiple envelope proteins in controlling fusion of BeWo cells raises the hypothesis that envPb1 could be involved in controlling the fusion of trophoblasts in vivo during placenta formation, as has been suggested for syncytin-1 and -2 (Blaise et al., 2003; Blond et al., 2000; Esnault et al., 2008; Mi et al., 2000; Malassiné et al., 2007). However, in a recent paper by Vargas et al. (2012), neither overexpression of EnvPb1 in BeWo cells nor siRNA knockdown of envPb1 upon forskolin induction supported the role of envPb1 in control of homotypic trophoblast cell fusion in vivo. This may stem from lack of expression of the cognate receptor or could be due to receptor interference in cell-culture models.

This is the first report to demonstrate stable knockdown of human envelope genes. Our available vectors are likely to find use in functional studies of fusion-competent human envelope genes in normal physiology and in research (or eventually therapy) of cancers and other human diseases associated with deregulated envelope expression. Syncytin-1 activity has been associated with human diseases such as multiple sclerosis (Antony et al., 2004; Perron et al., 2001), pregnancy disorders such as pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome (Knerr et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2001; Malassiné et al., 2008) and, lately, recent reports show that syncytin-1 expression may be linked to proliferation and fusion of breast cancer cells (Bjerregaard et al., 2006), endometrial carcinomas (Strick et al., 2007) and colorectal cancer (Larsen et al., 2009). The multitude of roles played by syncytin-1 and -2 and EnvPb1 in normal physiology and disease remain to be fully unravelled.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a postdoctoral fellowship to L. A. from the Alfred Benzon Foundation, grants from the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation and from the Lundbeck Foundation and US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AI41552, AI29329 and HL07470. We thank members of the Rossi laboratory for support and Luis C. Santos for assistance with production of lentiviral vectors. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

A supplementary table and supplementary methods are available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Aagaard L., Villesen P., Kjeldbjerg A. L., Pedersen F. S. (2005). The approximately 30-million-year-old ERVPb1 envelope gene is evolutionarily conserved among hominoids and Old World monkeys. Genomics 86, 685–691 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An D. S., Qin F. X., Auyeung V. C., Mao S. H., Kung S. K., Baltimore D., Chen I. S. (2006). Optimization and functional effects of stable short hairpin RNA expression in primary human lymphocytes via lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther 14, 494–504 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony J. M., van Marle G., Opii W., Butterfield D. A., Mallet F., Yong V. W., Wallace J. L., Deacon R. M., Warren K., Power C. (2004). Human endogenous retrovirus glycoprotein-mediated induction of redox reactants causes oligodendrocyte death and demyelination. Nat Neurosci 7, 1088–1095 10.1038/nn1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard B., Holck S., Christensen I. J., Larsson L. I. (2006). Syncytin is involved in breast cancer-endothelial cell fusions. Cell Mol Life Sci 63, 1906–1911 10.1007/s00018-006-6201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard B., Talts J. F., Larsson L. I. (2011). The endogenous envelope protein syncytin is involved in myoblast fusion. In Cell Fusions: Regulation and Control, pp. 267–275 Edited by Larsson L. I. New York: Springer; 10.1007/978-90-481-9772-9_13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise S., de Parseval N., Bénit L., Heidmann T. (2003). Genomewide screening for fusogenic human endogenous retrovirus envelopes identifies syncytin 2, a gene conserved on primate evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 13013–13018 10.1073/pnas.2132646100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise S., de Parseval N., Heidmann T. (2005). Functional characterization of two newly identified human endogenous retrovirus coding envelope genes. Retrovirology 2, 19 10.1186/1742-4690-2-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blond J. L., Lavillette D., Cheynet V., Bouton O., Oriol G., Chapel-Fernandes S., Mandrand B., Mallet F., Cosset F. L. (2000). An envelope glycoprotein of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W is expressed in the human placenta and fuses cells expressing the type D mammalian retrovirus receptor. J Virol 74, 3321–3329 10.1128/JVI.74.7.3321-3329.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad D. F., Pinto D., Redon R., Feuk L., Gokcumen O., Zhang Y., Aerts J., Andrews T. D., Barnes C. & other authors (2010). Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature 464, 704–712 10.1038/nature08516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C., Priet S., Ribet D., Vernochet C., Bruls T., Lavialle C., Weissenbach J., Heidmann T. (2008). A placenta-specific receptor for the fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, human syncytin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 17532–17537 10.1073/pnas.0807413105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr I., Beinder E., Rascher W. (2002). Syncytin, a novel human endogenous retroviral gene in human placenta: evidence for its dysregulation in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186, 210–213 10.1067/mob.2002.119636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E. S., Linton L. M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M. C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M. & other authors (2001). Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 10.1038/35057062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J. M., Christensen I. J., Nielsen H. J., Hansen U., Bjerregaard B., Talts J. F., Larsson L.-I. (2009). Syncytin immunoreactivity in colorectal cancer: potential prognostic impact. Cancer Lett 280, 44–49 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L. I. (editor) (2011). Cell Fusions: Regulation and Control. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Lee X., Keith J. C., Jr, Stumm N., Moutsatsos I., McCoy J. M., Crum C. P., Genest D., Chin D., Ehrenfels C. & other authors (2001). Downregulation of placental syncytin expression and abnormal protein localization in pre-eclampsia. Placenta 22, 808–812 10.1053/plac.2001.0722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malassiné A., Blaise S., Handschuh K., Lalucque H., Dupressoir A., Evain-Brion D., Heidmann T. (2007). Expression of the fusogenic HERV-FRD Env glycoprotein (syncytin 2) in human placenta is restricted to villous cytotrophoblastic cells. Placenta 28, 185–191 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malassiné A., Frendo J. L., Blaise S., Handschuh K., Gerbaud P., Tsatsaris V., Heidmann T., Evain-Brion D. (2008). Human endogenous retrovirus-FRD envelope protein (syncytin 2) expression in normal and trisomy 21-affected placenta. Retrovirology 5, 6 10.1186/1742-4690-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S., Lee X., Li X., Veldman G. M., Finnerty H., Racie L., LaVallie E., Tang X. Y., Edouard P. & other authors (2000). Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature 403, 785–789 10.1038/35001608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen K., Lichtenberg J., Thomsen P. D., Larsson L. I. (2004). Spontaneous fusion between cancer cells and endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 61, 2125–2131 10.1007/s00018-004-4200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron H., Jouvin-Marche E., Michel M., Ounanian-Paraz A., Camelo S., Dumon A., Jolivet-Reynaud C., Marcel F., Souillet Y. & other authors (2001). Multiple sclerosis retrovirus particles and recombinant envelope trigger an abnormal immune response in vitro, by inducing polyclonal Vbeta16 T-lymphocyte activation. Virology 287, 321–332 10.1006/viro.2001.1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudhomme S., Bonnaud B., Mallet F. (2005). Endogenous retroviruses and animal reproduction. Cytogenet Genome Res 110, 353–364 10.1159/000084967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruebner M., Strissel P. L., Langbein M., Fahlbusch F., Wachter D. L., Faschingbauer F., Beckmann M. W., Strick R. (2010). Impaired cell fusion and differentiation in placentae from patients with intrauterine growth restriction correlate with reduced levels of HERV envelope genes. J Mol Med (Berl) 88, 1143–1156 10.1007/s00109-010-0656-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søe K., Andersen T. L., Hobolt-Pedersen A.-S., Bjerregaard B., Larsson L.-I., Delaissé J.-M. (2011). Involvement of human endogenous retroviral syncytin-1 in human osteoclast fusion. Bone 48, 837–846 10.1016/j.bone.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick R., Ackermann S., Langbein M., Swiatek J., Schubert S. W., Hashemolhosseini S., Koscheck T., Fasching P. A., Schild R. L. & other authors (2007). Proliferation and cell-cell fusion of endometrial carcinoma are induced by the human endogenous retroviral Syncytin-1 and regulated by TGF-beta. J Mol Med (Berl) 85, 23–38 10.1007/s00109-006-0104-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas A., Thiery M., Lafond J., Barbeau B. (2012). Transcriptional and functional studies of human endogenous retrovirus envelope EnvP(b) and EnvV genes in human trophoblasts. Virology 425, 1–10 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villesen P., Aagaard L., Wiuf C., Pedersen F. S. (2004). Identification of endogenous retroviral reading frames in the human genome. Retrovirology 1, 32 10.1186/1742-4690-1-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]