Abstract

In the mouse liver, circadian transcriptional rhythms are necessary for metabolic homeostasis. Whether dynamic epigenomic modifications are associated with transcript oscillations has not been systematically investigated. We found in addition to mRNAs, several antisense-, linc- and micro-RNA transcripts showed circadian oscillations in adult mouse livers. Robust transcript oscillations were often accompanied by temporally correlated rhythmic histone modifications in promoters, gene bodies or enhancers, although promoter DNA methylation levels were relatively stable. Such integrative analyses identified oscillating expression of a previously undetected antisense transcript (asPer2) to the gene encoding the circadian oscillator component Per2. Robustness of transcript oscillations often accompanied rhythms in multiple histone modifications and recruitment of multiple chromatin-associated clock components. In summary, coupling of the locations of cycling histone modifications with one or more oscillating transcripts within their proximity enabled establishment of a temporal relationship between enhancers, genes and transcripts on a genome-wide, base-resolution scale in a mammalian liver. The results offer a framework to understand intricate dynamic regulation among metabolism, circadian clock, and chromatin modifications to maintain metabolic homeostasis.

Introduction

To adapt to changing energy intake and demand throughout the day, a large number of hepatic protein-coding transcripts show diurnal rhythms driven by a cell autonomous circadian oscillator, metabolic sensors responding to feeding-fasting cycle and rhythmic neuroendocrine signals (Hughes et al., 2009; Vollmers et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2006). Mice lacking circadian clock components or those with ad lib access to high fat diet exhibit dampened rhythms and succumb to metabolic diseases (Asher and Schibler, 2011). Conversely an imposed feeding-fasting cycle improves these rhythms and prevents diet induced obesity (Hatori et al., 2012), thus establishing the significance of rhythmic transcription for metabolic homeostasis.

The circadian oscillator is based on a transcription feedback loop in which the redox sensing BMAL1/CLOCK heterodimer drives transcription of Cry, Per, Ror, and Rev-erb genes. The CRY/PER complex inhibits BMAL1/CLOCK transcriptional activity, thus producing intrinsic oscillations in their own transcripts. REV-ERBs and RORs act as repressors and activators of Bmal1 and other clock genes thus driving their transcriptional oscillations (Cho et al., 2012) and reviewed in (Reddy and O’Neill, 2010)). These core oscillator components, their immediate targets (e.g. Dbp, Bhlhb2, Bhlhb41, Pgc1a, Pparg, Essr, Tef, Hlf, Nfil3) drive oscillating transcription of downstream genes (Dibner et al., 2010). Independent of the circadian oscillator, the feeding-fasting cycle can also drive oscillations by signaling through metabolic regulators including CREB, SREBP, ATF, and FoxO (Vollmers et al., 2009).

The circadian system imparts reciprocal regulation with metabolism. Cellular redox state, NAD, AMP/ATP ratio, biosynthesis of heme and several ligands for nuclear hormone receptors show diurnal rhythms (Asher and Schibler, 2011; Bass and Takahashi, 2010) which, in turn, reinforce the oscillating activities of several transcription factors. Additionally, metabolic products of S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) and coenzymes involved in histone and DNA methylation show diurnal rhythms. The methylation-dependent SAM metabolite S-adenosyl-homocysteine and the methylation-independent metabolite polyamines show oscillations in hepatocytes. Similar rhythms are observed in hepatic Coenzyme A, riboflavin, and TCA cycle intermediates involved in synthesis of acetyl-coA, FAD and α-ketoglutarate respectively (Atwood et al., 2011; Eckel-Mahan et al., 2012; Hatori et al., 2012).

There is increasing evidence that dynamic changes in histone modifications at circadian oscillator controlled loci contribute to oscillating transcription (Masri and Sassone-Corsi, 2010). BMAL1/CLOCK and PER/CRY complexes interact with several histone modifiers including WDR5, EZH, JARID1a, HDAC, and MLL to drive circadian oscillations in H3K4me3 and H3ac levels at the promoters of Per1, Per2, and Dbp (Brown et al., 2005; DiTacchio et al., 2011; Etchegaray et al., 2006; Katada and Sassone-Corsi, 2010; Naruse et al., 2004; Ripperger and Schibler, 2006), whereas REV-ERB and CRY interact with HDACs to drive circadian oscillations in H3ac at Bmal1 and Per promoters, respectively (Alenghat et al., 2008; Curtis et al., 2004; Feng et al., 2011). Genetic perturbations of these histone-modifying agents or of their interactions affect circadian transcriptional rhythms and disrupt metabolic homeostasis (Alenghat et al., 2008; Katada and Sassone-Corsi, 2010). In addition, CREB and FOXO3 also interact with p300/CBP (Kwok et al., 1994; van der Heide and Smidt, 2005). The p300/CBP complex carries out histone acetylation including H3K27 acetylation at both promoters and enhancers (Ramos et al., 2010; Visel et al., 2009).

Although dynamic circadian oscillations of histone modifications at a few genes have been examined, such regulation likely extend to a large part of the genome. Whole genome analyses of REV-ERB, HDAC3 occupancy and H3K9ac showed high H3K9ac at thousands of loci during morning and reduced H3K9ac at the same loci in the evening (Feng et al., 2011). Similarly, BMAL1 cistrome analyses identified its binding at hundreds of oscillating transcripts (Rey et al., 2011). These genome-wide studies hinted at global diurnal rhythms in the hepatic epigenome. Furthermore, both BMAL1 and REV-ERB binding at hundreds of sites outside the well-characterized promoters of protein-coding genes (Cho et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2011; Rey et al., 2011) implied these sites might specify enhancers or promoters of non-protein coding novel transcripts.

In this genome-wide integrative study we investigated the association between the dynamic hepatic transcriptome and its epigenome in adult mouse livers over the course of 24 hours. Using a deep-sequencing approach, we determined temporal genome-wide changes in the levels of strand-specific RNA, micro-RNAs, the histone modifications H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K36me3, as well as cytosine DNA methylation. We discovered circadian oscillation of protein-coding mRNAs as well as a number of overlapping-, linc- and mi-RNA transcripts. Although promoter DNA methylation showed no significant changes associated with transcript oscillations, oscillations in histone modifications were pervasive and temporally correlated with the transcript oscillations at proximal loci. Beyond gene bodies and promoters oscillations in histone modifications were also detected atenhancers, allowing establishment of functional transcript-enhancer associations.

Results

Deep sequencing methods identified circadian changes in the liver transcriptome and epigenome

Mice held under constant condition were sacrificed every 3h and their livers were collected. Strand-specific poly(A)+ RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq), Chromatin-immunoprecipitation-Sequencing (ChIP-Seq) on H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K36me3, H3K4me1 and H3K9ac throughout a 24-hour day (CT0-24) (Figure S1A,B,C) were performed. These five histone modifications define, alone or in a combinatorial manner, major chromatin domains at promoters (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K9ac), gene bodies (H3K36me3), and enhancers (H3K27ac, H3K4me1). Additionally, the DNA methylomes of the liver at two opposing time points (CT 9, 21) were determined using whole genome bisulfite sequencing (MethylC-Seq) (Lister et al., 2008).

To test sufficiency of sequencing depth for detection of circadian oscillations, mapped sequence tags were visualized for two known oscillating genes (Figure S2A,B); BMAL1/CLOCK driven xenobiotic metabolism regulator Dbp, and circadian oscillator- and SREBP-driven Elovl3 (Anzulovich et al., 2006). In addition to confirming oscillations in H3K4me3 and H3K9ac modifications at specific sites in the promoter and the first intron of Dbp (Ripperger and Schibler, 2006), we also found synchronous oscillations in H3K4me3 and H3K27ac at the promoter and H3K36me3 in the gene body, peaking in the late afternoon (CT9) when transcript levels also peaked (Figure S2A). In contrast, promoter H3K4me1 levels peaked when transcript levels were at their lowest. The Elovl3 locus also showed oscillations in transcript and in histone modifications (Figure S2B), but the phase of oscillations was distinct from Dbp. In summary, these results demonstrate the robustness of these assays in detecting oscillations.

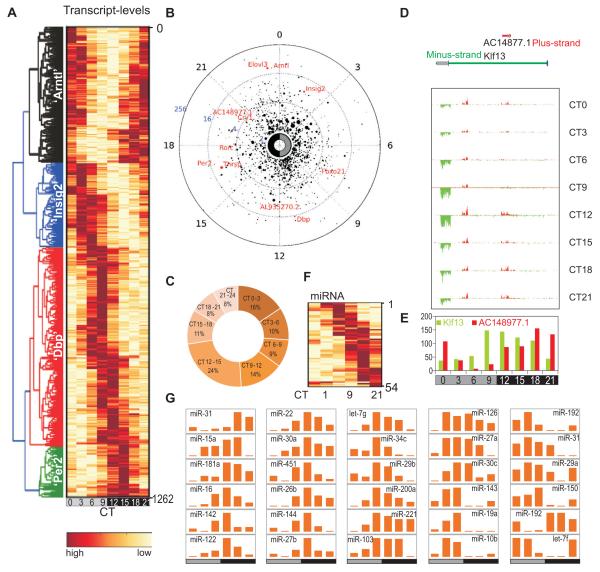

Strand-specific RNA-Seq uncovers a wide range of oscillating RNA species in their genomic context

A total of 14,492 active genes were identified, many of which were undetectable by high-density array (HDA)-based methods (Hughes et al., 2009) (Figure S3A). Transcript levels of active genes correlated with liver RNA-Seq dataset from an independent laboratory (Figure S3B) (Mortazavi et al., 2008). A set of 1,262 (9% of expressed) oscillating transcripts (Figure 1A,B Table S1) were identified (COSOPT (Straume, 2004) p<0.02, 20<period (τ)<28h) with at least 2-fold peak to trough ratio. Of the 1,262 oscillating transcripts, 1,160 were protein-coding, including well-characterized genes implicated in metabolic regulation such as Arntl (Bmal1), Insig2, Fbxo21, Dbp, Thrsp, Per2, Rorc, Cry1, and Elovl3 (Figure 1A,B) (Hughes et al., 2009; Panda et al., 2002; Ueda et al., 2002). 446 protein-coding transcript identified by RNA-Seq were also scored oscillating and shared similar phases of expression in the earlier HDA-based detection (R2=0.89) (Figure S3C, Table S2), thus establishing the RNA-Seq approach as reproducible. Additionally, 135 oscillating mRNAs and 102 oscillating non-protein-coding transcripts identified by RNA-Seq were either undetectable or not represented in the HDA platform (Figure S3D, Table S3). The times of peak levels of the 1,262 oscillating transcripts were distributed throughout 24h, with moderate prevalence in the subjective morning (CT21-CT3: 301 transcripts or ~24%) and subjective evening (CT9-CT15; 373 transcripts or 37.5%) (Figure 1C) coinciding with the end of nocturnal feeding and the diurnal fasting period in mice, respectively. Overall, the 1,262 oscillating transcripts showed median expression that was comparable to all active genes and peak to trough expression changed mostly under 10-fold (Figure S3E,F).

Figure 1. Strand specific and small RNA-Sequencing identified oscillating sense-, antisense-, and mi-RNA transcripts in the mouse liver.

1,262 oscillating transcripts are shown in a (A) heatmap or (B) polar plot. In polar plot, peak-phase is shown along the radial coordinate, the distance to the center of the circle shows the amplitude of transcript oscillation. Average transcript levels over 24 h are proportional to the radius of the marker. Examples of known oscillating transcripts are shown in red. (C) Frequency plot percentage of oscillating transcripts with peak phase of expression binned in 3h over 24h. (D) Klf13/AC148977.1 locus shows oscillations in both sense and antisense transcripts. RNA levels on the plus (red) and minus (green) strands are in 150 bp bins and visualized for each time point. (E) Antisense transcript AC148977.1 (red) and Klf13 (green) are plotted. (F) 54 oscillating miRNAs are shown in a heatmap. (G) Normalized tag counts of example miRNAs show circadian oscillations.

The strand-specific RNA-Seq readout enabled identification of oscillating transcripts in their genomic context. Nearly 25% (336 genes) of loci with oscillating transcripts were in close proximity (<500 bp or <3 nucleosomes) or overlapped with nearby loci (Table S4, Figure S4A). Only 11 of these overlapping pairs (22 loci out of 336 or <10%) showed oscillation of both transcripts (Table S5, Figure S4B), suggesting genomic overlap does not increase probability of the pair to exhibit circadian oscillation. For example, although the nuclear hormone receptor implicated in circadian clock and hepatic fatty acid metabolism Rev-erbα (NR1D1) transcript robustly oscillates, the transcript from its overlapping gene-pair thyroid hormone receptor alpha (Thra) did not pass the criteria for oscillation (Figure S4B). Additionally, 36 loci with oscillating transcript levels were completely encapsulated within other loci (Table S6), of which four showed oscillating transcript (Figure S4B). An oscillating 3.8 kb lincRNA AC148977.1 transcript and a second un-annotated transcript of 3.6 kb with peak phase of oscillation in the early morning are located inside the 47.5 kb zinc-finger transcription factor Klf13 locus, whose transcript levels also show clear oscillations with peak expression in the evening (Figure 1 D,E).

Transcript oscillations were not limited to protein-coding loci. Out of 123 detected lincRNAs, 19 showed robust oscillations (Table S1). Mapping the sequence reads from small RNA-Seq to annotated micro-RNAs (miRNAs) identified 258 expressed miRNAs, including several miRNAs expressed in the mouse liver, such as miR -33, -122, -103, -107, -221 and the Let-7 family of miRNAs (Fornari et al., 2008; Frost and Olson, 2011; Jopling et al., 2005; Najafi-Shoushtari et al., 2010; Rayner et al., 2010; Trajkovski et al., 2011). In addition to miRNA-122, the only miRNA previously shown to have circadian oscillations in the liver (Gatfield et al., 2009), we identified circadian oscillations in 53 miRNAs (Figure 1F,G, Table S7). Among the oscillating miRNAs, Let-7, miR-33, miR-103, and miR-122 have already been implicated in liver function (Frost and Olson, 2011; Gatfield et al., 2009; Rayner et al., 2010; Trajkovski et al., 2011) and thereby add an additional mode of circadian regulation to physiology and metabolism.

DNA methylation does not display robust changes at transcriptionally oscillating loci

Oscillation in DNA methylation is associated with sub-circadian (<24h) transcriptional oscillations in cultured cells (Kangaspeska et al., 2008; Metivier et al., 2008). We tested whether hepatic DNA methylation levels change between late afternoon (CT9) and late night (CT21), when two large clusters of oscillating transcripts (704 loci) approach their peak levels (Figure 1C).

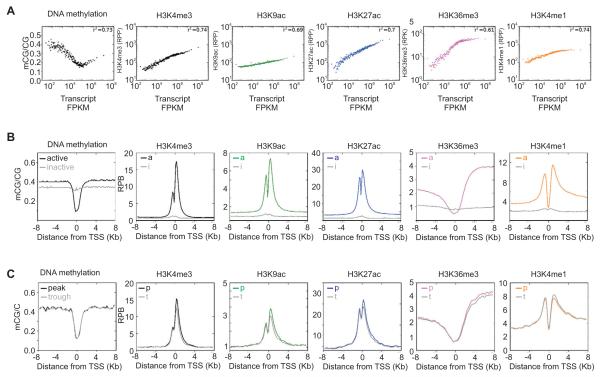

DNA methylation in the mouse liver occurred almost exclusively in a CG context (99.99%). Across all active loci, promoter methylation was inversely associated with transcript levels (Figure 2), except for highly expressed loci (18% of all active loci, FPKM > 106) which contained slightly higher promoter CG methylation (Figure 2A). A comparison of promoter DNA methylation levels in the oscillating genes peaking at CT9 or CT21 and even those with >10-fold change between peak and trough level of RNA revealed no differences (<1%, Table S8) in promoter DNA methylation levels between peak and trough times of transcription (Figure 2C, S5), although histone modifications showed clear differences (discussed in the next section). A systematic analysis to detect time-dependent differentially methylated regions (DMR) identified only 18 DMRs, 16 of which fell into genes, none of which showed clear oscillating transcription (Table S9). In summary, circadian oscillation in liver DNA methylation is either very rare, or small in amplitude.

Figure 2. Temporal changes in histone modifications at oscillating loci are distinct from differences in histone modification signatures at expressed and silent loci.

(A) Scatter plot of transcript levels (x-axis) and the indicated epigenomic feature (y-axis). RNA, histone modification and DNA methylation at promoter or gene body regions of 14,492 expressed genes were grouped in bins of 100 and median normalized. H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K9ac and H3K27ac are shown as reads per promoters (RPP) while H3K36me3 is shown as reads per kilobase of gene body (RPK). DNA methylation is shown as the ratio of methylated CG to total CG in the promoters (±4 kb). (B) Average enrichment patterns of histone modifications and the extent of DNA methylation is shown in the promoter areas of active vs. inactive genes. The y-axis shows the extent of enrichment in reads per 150 bp bins (RPB). (C) Average DNA methylation and histone modifications in the promoters of ~700 oscillating genes at either peak (p) or trough (t) of transcript levels.

Widespread changes in patterns of histone modifications along a circadian timescale

The five investigated histone modifications H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, and H3K36me3 were enriched in actively transcribed genes (Figure 2B) correlated (R2=0.61-0.74) with transcript levels (Figure 2A). Promoter H3K4me1 and gene-body H3K36me3 reached a plateau in highly expressed loci (Figure 2A)), thus implying circadian changes in these histone modifications may be modest. Unlike the wide dynamic range of transcript levels spanning several orders of magnitude, the dynamic range of histone modifications spanned only up to one order of magnitude due to the finite number of sites accessible for histone modification.

All five histone modifications tested showed clear changes between peak and trough levels of 704 oscillating transcripts (Figure 2C) that reached maximum expression at CT9 and CT21. Normalized average levels of H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K36me3 were higher at the peak time of transcription and were lower at the trough time of transcription in 704 oscillating loci (Figure 2C), but did not approach the chromatin signature of inactive loci. We systematically examined circadian oscillations in the levels of the most dynamic modifications, H3K4me3 and H3K27ac.

Oscillating H3K4me3 and transcript levels define oscillating transcript-promoter pairs

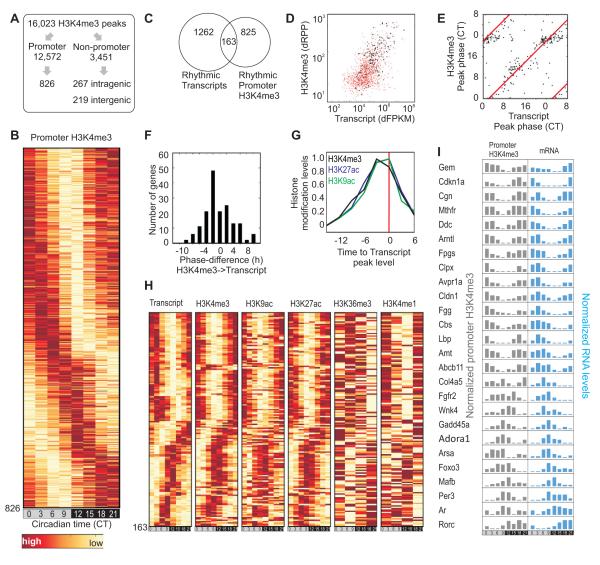

We identified robustly oscillating H3K4me3 levels at 826 promoters (TSS±4 kb, COSOPT p<0.02, 20h<τ< 28h, peak to trough FC≥1.5) (Figure 3A,B, Table S10), of which 154 were associated with genes with no detectable transcript levels at two or more of the eight time points. These undetectable transcripts represent largely uncharacterized transcripts or poly(A)− transcripts, which were underrepresented in the poly(A)+ pool selected for transcript sequencing. Of the remaining 662 oscillating H3K4me3 promoter peaks, 163 were associated with robust transcript oscillations (Figure 3C, Table S11) forming oscillating transcript-promoter pairs. The majority of promoters with oscillating H3K4me3 peaks were associated with oscillating transcripts, which did not meet at least one of the three criteria for robust oscillation (Figure 3D). The 163 oscillating transcript-promoter pairs were enriched for circadian oscillator components and key regulators of liver metabolism including Bmal1, Cry1, Per1, Per2, Per3, Rorc, Foxo3, Gadd45a, Fgfr2, Mthfr, Cdkn1a, Rev-erbα, Dbp, Tef, and Nfil3.

Figure 3. Oscillating H3K4me3 identified highly dynamic histone modifications at promoters.

(A) Schematics for identification of oscillating H3K4me3 peaks. (B) Heatmap rendering of oscillating promoter H3K4me3 levels at 826 loci. (C) Venn diagram of overlap between oscillating transcripts and oscillating H3K4me3 at their promoters. (D) The absolute changes of transcript (dFPKM) and H3K4me3 (dRPP) levels of 1,262 oscillating genes are shown in a scatter plot in red. 163 loci with oscillating H3K4me3 levels are shown in black. (E) Scatter plot of the peak phase of transcript (x-axis) and H3K4me3 (y-axis) at 163 oscillating transcript-H3K4me3 pairs. (F) Difference in peak phase between transcript and H3K4me3 levels. (G) Histone modification levels in 163 oscillating loci are normalized relative to transcript peak time. (H) Heat map representation of the levels of transcript, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac H3K36me3 (gene body) and H3K4me1 levels in 163 oscillating transcript-promoter H3K4me3 pairs. (I) Examples of temporally correlated oscillating promoter H3K4me3 levels and transcript. Gene symbols, normalized histone modification levels and transcript levels are shown.

In these 163 loci, temporal changes in promoter H3K4me3 and other histone modifications were closely coupled to oscillations in transcript levels (Figure 3 E-I). Gene-body H3K36me3, which was measured at only four time points, also showed clear, albeit noisy oscillations, which peaked at roughly the same time as associated transcript levels. Promoter H3K4me1, which likely results from demethylation of H3K4me3 during poised basal period of transcription, showed oscillations with its peak phase opposite to that of associated transcript levels. Overall, these data reveal genomic loci that undergo highly dynamic and reversible changes to their local chromatin environments on a circadian timescale.

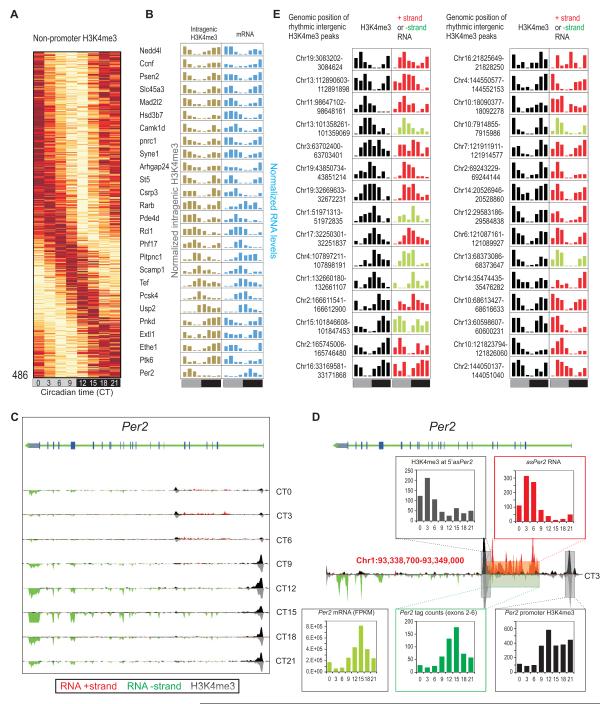

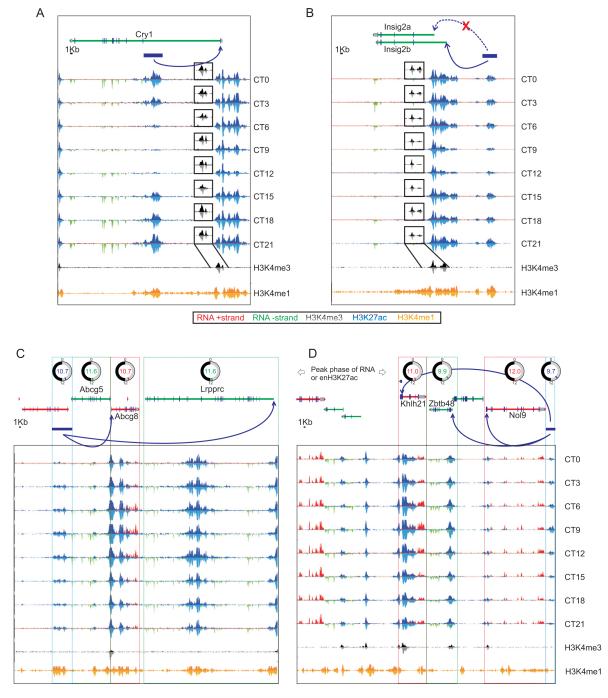

Oscillating H3K4me3 outside of annotated promoters identified novel transcripts including asPer2

In addition to rhythmic H3K4me3 at bona fide promoters, 267 intragenic and 219 intergenic H3K4me3 peaks oscillated (Table S12, S13, S14 and Figure 4A,B). The majority of these non-promoter peaks were co-enriched for H3K9ac or H3K27ac and likely mark alternative TSS in gene bodies or TSS of novel transcripts. Of the 267 oscillating peaks in gene bodies, 47 are located in 44 oscillating genes (Table S12) including Psen2, Camk1d, Rarb, Syne1, Hsd3b7, and Ccnf (Figure 4B). The peak phases of gene body H3K4me3 levels was synchronous with the corresponding rhythmic transcript, except at two loci: AC156021.1, and Per2. Both peaks are oscillating anti-phasic to the respective genes they are located within and both peaks are accompanied with oscillating levels of antisense (AS) RNA. The intragenic H3K4me3 levels peak at CT6 and are temporally correlated with an AS transcript of Per2 (asPer2) (Figure 4C). The asPer2 RNA starts at the H3K4me3 peak 16.5 kb downstream of Per2 TSS and extends for 10.2 kb into the 5′UTR of the sense transcript. The asPer2 expression reaches its maximum at CT3, ~12 h after Per2 transcript peaks (Figure 4D). Antisense transcript of Neurospora clock component frq has been shown to modulate the intrinsic oscillation and light induced change in frq transcript (Kramer et al., 2003). Accordingly, asPer2 transcription might add another level of control to Per2 transcription.

Figure 4. Oscillating H3K4me3 marks unannotated transcribed loci including asPer2.

(A) Heatmap rendering of oscillating non-promoter H3K4me3. (B) Examples of genes with intragenic oscillating H3K4me3 and oscillating transcripts showing temporally correlated H3K4me3 and transcript rhythms except Per2. (C) Per2 locus shows rhythmic expression of both sense and an antisense transcript. Transcript (red/green) and H3K4me3 (black/grey) levels, binned in 150 bp bins for both ‘+’ and ‘−’ strands are shown. (D) Data for CT3 is shown magnified to highlight the asPer2 transcript. Inset histograms report oscillations in H3K4me3 levels at the potential TSS of asPer2, asPer2 RNA levels, Per2 mRNA, transcript from the sense strand in the regions corresponding to the asPer2 transcript, and rhythm in H3K4me3 at the Per2 TSS. Corresponding regions of the locus are shown in colored boxes. (E) Examples of oscillating intergenic H3K4me3 peaks and associated transcripts. Normalized H3K4me3 levels (black) and transcript tag counts from the plus strand (red) or minus strand (green) in the proximal 10 kb region at eight time points through 24h are shown.

Most of the 219 oscillating intergenic H3K4me3 peaks are relatively low in average H3K4me3 enrichment (promoter: 108.1, gene body: 47.7, intergenic: 25.2 reads per peak (RPP)) and likely mark TSS of novel transcripts expressed at low levels. Indeed, 179 were associated with detectable (>10 reads in adjacent ±10kb) RNA levels (Table S14 and Figure 4E). In summary, the combination of non-promoter H3K4me3 rhythm with strand-specific RNA-Seq revealed novel rhythmic transcripts.

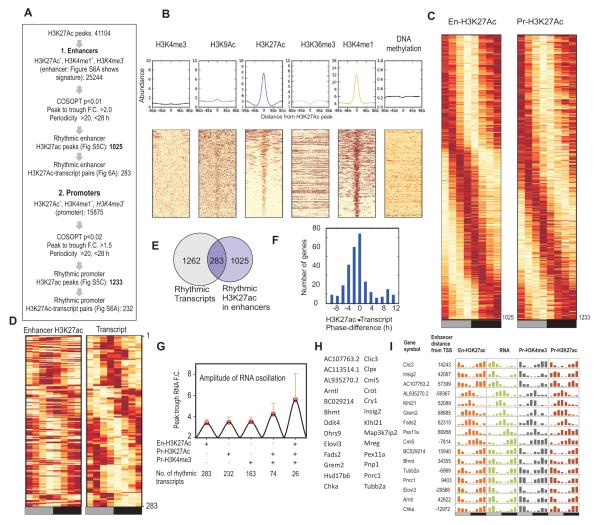

Oscillating H3K27ac defines oscillating enhancers

The role of enhancers in circadian gene expression has been limited. We identified 25,244 H3K27ac+/H3K4me1+/H3K4me3− peaks, which we defined as enhancers (Figure 5A, B) (Guenther et al., 2007; Roh et al., 2006). Since H3K4me1 marks enhancers and changes in H3K27ac levels define enhancer activity (Creyghton et al., 2010), H3K27ac levels at these regions were tested for oscillations. Unlike the promoter histone modifications spatially linked to TSS, H3K27ac only defined spatially unrestrained active enhancer sites. Therefore, we used more stringent criteria than used for H3K4me3 (COSOPT p<0.01, 20< τ <28h, peak to trough ratio >2) and found 1,025 oscillating enhancers (Table S15, Figure 5C). Within 200 kb (±100 kb) flanking each oscillating enhancer, accounting for a sample space of 205 Mb or < 7% of the genome, 283 oscillating enhancers-transcript pairs (27.6% of oscillating enhancers; Figure 5D-F, S6A Table S16) were identified. Granger’s causality analysis found a significant correlation between the times of peak H3K27ac levels at enhancers and associated transcript oscillations (p<2*10−38). In addition to enhancers, oscillating H3K27Ac was also defined at promoters of oscillating transcripts (Figure 5A, C). Oscillating H3K27Ac, at both enhancers and promoters along with promoter H3K4me3 oscillations act synergistically to boost transcript oscillations (Figure 5G-I).

Figure 5. H3K27ac defines oscillating enhancers.

(A) Flowchart for identification of rhythmic H3K27ac at enhancers and promoters. (B) Histogram and heatmap rendering of various histone modifications and DNA methylation levels at enhancers. (C) Heatmap representation of oscillating H3K27ac at enhancers and promoters. (D) Heatmap representation and (E) Venn diagram of 283 oscillating enhancers and proximal (within 200kb) oscillating transcripts. (F) Difference in peak phase between RNA and enhancer H3K27ac is shown as a histogram. H3K27ac levels preceded RNA levels. (G) Synchronous histone modification rhythms correlate with improved amplitude of transcript oscillations. Average (+ s.d.) peak:trough ratio (amplitude) of oscillating transcripts with oscillating enhancer H3K27ac, promoter H3K27ac, promoter H3K4me3 or combinations of histone modification rhythms are shown. Number of transcripts that meet these criteria are shown below. (H). Gene names of 26 loci and (I) example loci with robust oscillations in RNA, promoter H3K4me3, promoter H3K27ac and enhancer H3K27ac

Some of the oscillating enhancers highlight nodes for circadian control of metabolic regulators. Oscillating enhancers were mapped to Cry1, Bmal1, and Insig2 (Figure 6A, S6B). The oscillating enhancer in the first intron of the Cry1 locus harbors a functional REV-ERB/ROR binding element that functions in concert with oscillating BMAL1 driven transcription from its canonical promoter (Rey et al., 2011; Ukai-Tadenuma et al., 2011). Although two isoforms of cholesterol metabolism regulator Insig2 are expressed in the liver, only one oscillates under the regulation of REV-ERBα to maintain cholesterol homeostasis (Le Martelot et al., 2009). The newly identified enhancer 42 kb upstream of the well-characterized TSS shows oscillating H3K27ac levels in phase with Insig2 transcript (Figure 6B) and also harbors a REV-ERB/ROR element.

Figure 6. Enhancer H3K27ac oscillation temporally correlates with transcript oscillation from proximal gene or cluster of genes.

Transcript (red/green) and H3K27ac (blue/light blue) read density is are illustrated at (A) Cry1 and (B) Insig2 loci at eight time points (rowsH3K4me3 and H3K4me1 read density is given as a reference in the bottom panel and H3K4me3 is shown as insets at each time points (black). Enhancers are indicated as blue bars and arrows indicate promoters of target genes. (C and D) Single enhancers drive transcription of multiple proximal genes. Gene models, peak phase of oscillating transcripts are shown on top. Blue horizontal bars denote enhancer regions marked by oscillating H3K27ac and absence of H3K4me3.

Oscillating transcript levels of several genes (examples-Bhmt, Dnmt3b, Ndrg1, Fads2, Gadd45a, Asap2, Fm02) temporally correlated with multiple oscillating proximal enhancers (Figure S6A). Conversely, single enhancers also mapped in the proximity of multiple genes with synchronously oscillating transcripts (Figure 6C,D). H3K27ac levels in an enhancer adjacent to Abcg5, Abcg8, and Lrprrc genes were temporally correlated to their transcript levels (Figure 6C). Both Abcg5, and Abcg8 encode two half-transporters for excretion of bile acid (Berge et al., 2000). Coordinated circadian oscillation of the transcripts of Abcg5, Abcg8 and of Lrpprc, master regulator of mitochondrial mRNA synthesis (Ruzzenente et al., 2012), likely ensures coordinated production and efflux of bile acids from hepatocytes as well as robust mitochondrial protein synthesis to protect against potential bile acid toxicity (Palmeira and Rolo, 2004). Similarly, another circadian enhancer in chromosome 4 peaks at ~CT10 with the transcripts of Nol9, Klhl21 and Zbtb48 following shortly after (Figure 6D). Although the functions of these three genes are yet to be characterized they all encode nuclear proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. The arrangement of genes at these two different enhancers is conserved in the human genome, thus emphasizing a physiological need for their correlated expression.

Discussion

Integration of RNA-Seq, ChIP-Seq and MethylC-Seq data differentiated dynamic and static parts of the epigenomic environment of oscillating genes. Although we could not conclusively detect oscillations in DNA methylation, circadian changes at specific nucleotide positions or in response to different metabolic states cannot be ruled out. Stringent criteria used to detect circadian transcriptome and chromatin states revealed robust transcript oscillation linked to oscillations in different histone modifications. Similar to histone H3K4me3, COSOPT analyses of promoter H3K27ac identified 1,233 promoters with oscillations in H3K27ac with their phase of expression represented throughout the day (Figure S7A). Among the 1,262 oscillating transcripts, 232 exhibited robust oscillations in promoter H3K27ac (Table S19, Figure S7A) with temporally correlated oscillations in transcripts, and other histone modifications (Figure S6A,B).

Throughout the genome more than 3,000 loci showed oscillating levels of either H3K4me3 and/or H3K27ac with peak/trough fold change >1.5 fold. Although we objectively monitored temporal changes in only two “core” histone modifications, several histone modifications (e.g. H2A.Z, H2BK5/12/20/120ac, H3K4me1/2/3, H3K4/9/18/27/36ac, H3K9me1, and H4K5/8/91ac) are co-regulated (Wang et al., 2008) and are likely to show circadian oscillations.

Although we identified 1,262 oscillating transcripts, relatively smaller overlapping subsets accompanied robust oscillation in histone modification rhythms. The criteria used for defining circadian oscillation, post transcriptional processing steps, and synergistic interaction among histone modification rhythms or among circadian transcription factors for robust transcript oscillation might explain such insufficient overlap.

The oscillating transcripts often show modest changes between peak and trough levels, with a median fold-change <2 in several studies (Hughes et al., 2009; Panda et al., 2002; Ueda et al., 2002; Vollmers et al., 2009). The finite number of sites on histone tails available for modification in combination with the limited number of histones per nucleosome dampens the magnitude of detectable changes for oscillating histone modifications. Since oscillating transcripts with high amplitude (peak to trough ratio) often reproduce between independent studies, we used stringent FC criteria for defining oscillating transcriptome and chromatin modifications. For example, although 163 loci showed robust rhythms in both transcript and promoter H3K4me3, in a scatter plot of absolute change (as opposed to fold-change) in transcript and promoter-H3K4me3 levels it is apparent that circadian changes in transcript levels positively correlate with the changes in promoter H3K4me3 (Figure 3D). Therefore, at the cost of decreased reproducibility, less stringent thresholds might reveal more oscillating transcripts, H3K4me3 peaks and transcript-promoter pairs.

We directly tested whether oscillations in promoter H3K4me3 and transcripts are uncoupled. Using reverse cut-offs (<1.5 maximum:minimum FC for RNA and oscillating promoter H3K4me3 or <1.2 fold change for H3K4me3 and oscillating RNA), we identified only 55 oscillating H3K4me3 peaks associated with non-oscillating RNA and 22 oscillating transcripts associated with constant H3K4me3 levels (Table S17,S18, Figure S6E). Hence, for a large number of oscillating loci there exists a positive correlation between absolute changes of promoter H3K4me3 and RNA. Nevertheless, discordance between transcript- and histone modification-rhythms either in phase or in levels in several loci indicates post-transcriptional RNA processing mechanisms likely contribute to transcript oscillations.

We also found synergistic contributions from multiple histone modification and transcription factors oscillations on transcript oscillations. (Table S20). A subset of 26 oscillating transcripts with detectable oscillations in promoter H3K4me3 and H3K27ac as well enhancer H3K27ac showed elevated average amplitude of oscillation when compared with subsets with only one or two detectable oscillating histone modification features (Figure 5G-I).

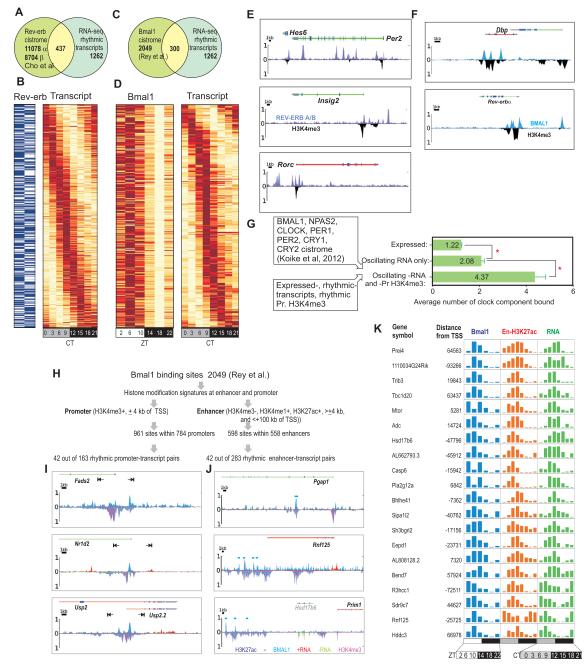

Next, we integrated the results from three independent circadian transcription factor cistrome studies (Cho et al., 2012; Koike et al., 2012; Rey et al., 2011). REV-ERB-α and -β binding sites were found at 437 oscillating transcripts (Figure 7A,B), whereas BMAL1 binding sites (Rey et al., 2011) were found at 300 oscillating transcripts (Figure 7C,D). Spatial enrichment of REV-ERB or BMAL1 in these binding sites often peaked in proximity but not overlapping with peaks of histone modifications (Figure 7E,F), possibly indicating the exclusion of histones through the binding of transcription factors. Conversely, we tested if binding of circadian transcription regulators correlates with oscillating transcription and histone modifications, by mapping the cistromes of seven different circadian regulators (Koike et al., 2012) to our dataset. An average of 1.22 circadian regulator binding sites was found at each of the 14,492 expressed genes. Oscillating transcripts had significantly more binding sites (2.08 ± 0.12, s.e.m.) and oscillating transcript-promoter H3K4me3 pairs had twice more (4.37 ± 0.47) clock factors (Figure 7G).

Figure 7. Synergistic role of circadian transcription regulator binding and histone modification rhythms in driving robust transcript opsillation.

(A) Venn diagram and (B) heatmap rendering of Rev-erb occupancy (blue present, white absent) and oscillating transcripts at 437 loci. (C) Venn diagram and (D) heatmap showing 300 loci with rhythmic transcripts also show rhythmic binding of BMAL1.(E) Read density of REV-ERB α and β (light blue and purple) and H3K4me3 (black) are shown as histograms for the Per2, Insig2, and Rorc loci. (F) Read density of BMAL1 (ZT6) and H3K4me3 (CT6) are shown as histograms for the Dbp and Nr1d1 loci. REV-ERB α and β (light blue and purple), BMAL1 (blue), and H3K4me3 (black) are binned in 150 bp bins. (G) Mapping the binding sites of 7 different circadian regulators to expressed genes revealed propensity of their binding to genes with oscillating transcripts and oscillating promoter H3K4me3. Average (+ s.e.m.) number of binding sites at all expressed genes (n=14, 492), rhythmic transcripts (n=1262) and rhythmic transcreipt-promoter H3K4me3 pairs (n=163) are shown. (H) Mapping BMAL1 binding sites to promoter and enhancers. (I) Examples of rhythmic promoter-transcript pairs or (J) rhythmic enhancer-transcript pairs with BMAL1 occupancy at promoters or enhancers. Note at Usp2 locus promoter signature and BMAL1 occupancy coincides with an alternate TSS that defines Usp2.2 transcript variant. (K) Examples of genes with oscillating transcript and temporally correlated BMAL1 in enhancers. Normalized transcript and enhancer-H3K27ac and BMAL1 levels at eight (transcript, H3K27ac) or six (BMAL1) different time points are shown.

Additionally, circadian transcription regulator binding was not limited to promoters. Out of 2,049 BMAL1 binding sites in the mouse genome (Rey et al., 2011), 47% (961) overlapped with 785 promoters (co-enriched for H3K27ac, H3K4me3) and 30% (598 sites) overlapped with 558 enhancer regions (co-enriched for H3K27ac, H3K4me1, but not H3K4me3). BMAL1 binding sites (Rey et al., 2011) were not only present at the promoters of 42 out of 163 (25%) oscillating transcript-promoter pairs, but also at the enhancers of 42 out of 283 (15%) oscillating transcript-enhancer pairs (Tables S21 and S22, Figure 7H-J). Therefore, in addition to BMAL1’s well described role in transcription regulation from promoter, it is also recruited to oscillating enhancers (Figure 7H-K).

In summary, integrative analyses of the epigenome in the liver on the circadian timescale has expanded the “circadian transcriptome” beyond protein-coding genes by revealing a large number of non-coding and regulatory RNAs. It has also demonstrated that oscillating transcription is associated with circadian oscillations in histone modifications in promoters, gene bodies, and enhancers, but not with robust rhythms in DNA methylation. These data offer a framework to understand the epigenomic basis for circadian transcription and identified the oscillation of hundreds of mRNA, ncRNA and miRNAs transcripts that exert temporal regulation of liver metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Salk Institute.

RNA-Seq

Ten-week old male C57BL/6J mice from Jackson Laboratories were entrained to a 12:12 LD cycle for 14 days and subsequently released into constant darkness. On day two in constant darkness four mice were sacrificed and liver samples were taken every three hours for 24 hours. Liver samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and processed to a fine powder using a mortar and a pestle. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy columns (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNAs from all four mice were pooled and subsequently enriched for poly-adenylated RNA using the Oligotex mRNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Directional RNA-Seq libraries were generated following the standard SOLiD protocols. Time points were barcoded and sequenced on the SOLiD4 sequencer. The resulting 50 bp reads were aligned to the mouse genome (build mm9) using Bioscope™ (version 1.3). Transcript levels were determined using Cufflinks (version 1.0.0) (Trapnell et al., 2010) and transcript abundance was expressed as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) values.

ChIP-Seq

Samples were collected as for RNA-Seq. Fresh liver samples were cut into 1mm3 pieces and cross-linked in 1% Formaldehyde for 15min. 0.125% Glycine was added for five minutes and samples were washed twice in PBS. Cross-linked liver pieces were homogenized using a 7ml B-dounce. ChIP and sequencing in Illumina GAII sequencer is described in supplemental material.

MethylC-Seq

DNA was extracted with a DNeasy-Tissue Kit (Qiagen). DNA was sonicated, ligated to adapter and bisulphite converted (Methylcode Kit Invitrogen) and amplified with four cycles of PCR as described previously (Lister et al., 2009). Each sample was sequenced on a GAII sequencer (Illumina). A total of >13 gigabases (Gb) of genomic DNA were sequenced for each methylome amounting to ~4.85 (CT9) and ~5.6 (CT21)-fold coverage across the genome. Such depth of coverage has successfully identified differentially methylated regions in mammalian cells (Lister et al., 2011)

Small-RNA seq

For small RNA sequencing, mice were entrained to light:dark cycle and released into constant darkness as described before. Whole livers from mice were collected at 4 h interval over 24 h and individually homogenized in 0.5ml RNA-bee (AMSbio, CS-501B), and then immediately diluted using an additional 1ml RNA-bee. RNA was extracted as described in the manufacturer’s protocol, and re-suspended in 20 μl DEPC-H2O. Small RNA cloning was performed as described in the Illumina Small RNA Digital Gene Expression v1.5 preparation protocol, except that we used custom oligonucleotide adapters and primers that matched those of the Illumina TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation protocol.

Data analysis

Islands of enrichment (peak) of each chromatin modification were determined as described in the supplemental methods. Oscillations were analyzed and scored using the pMMC-beta value as determined by the COSOPT algorithm.

Data-availability

Raw sequencing data was deposited at SRA under the access number ‘SRA025656’. The data is available in visual form under www.circadian.salk.edu. Normalized data tracks for the UCSC Genome browser, processed data as well as list of genes used in figures can be downloaded at www.circadian.salk.edu.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

-

-

Hepatic linc-, antisense- and micro-RNAs exhibit circadian oscillations

-

-

Levels of histone modifications oscillate in the promoters and enhancers of hundreds of oscillating transcripts

-

-

Genome-wide epigenomic oscillations show strong temporal correlation with transcript levels

-

-

Rhythmic transcripts and enhancer histone modifications link genes with their regulatory sequences

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alenghat T, Meyers K, Mullican SE, Leitner K, Adeniji-Adele A, Avila J, Bucan M, Ahima RS, Kaestner KH, Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature. 2008;456:997–1000. doi: 10.1038/nature07541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzulovich A, Mir A, Brewer M, Ferreyra G, Vinson C, Baler R. Elovl3: a model gene to dissect homeostatic links between the circadian clock and nutritional status. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2690–2700. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600230-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Schibler U. Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell metabolism. 2011;13:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood A, DeConde R, Wang SS, Mockler TC, Sabir JS, Ideker T, Kay SA. Cell-autonomous circadian clock of hepatocytes drives rhythms in transcription and polyamine synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18560–18565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115753108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010;330:1349–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Ripperger J, Kadener S, Fleury-Olela F, Vilbois F, Rosbash M, Schibler U. PERIOD1-associated proteins modulate the negative limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Science. 2005;308:693–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1107373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Zhao X, Hatori M, Yu RT, Barish GD, Lam MT, Chong LW, Ditacchio L, Atkins AR, Glass CK, Liddle C, Auwerx J, Downes M, Panda S, Evans RM. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-alpha and REV-ERB-beta. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, Boyer LA, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AM, Seo SB, Westgate EJ, Rudic RD, Smyth EM, Chakravarti D, FitzGerald GA, McNamara P. Histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin remodeling and the vascular clock. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7091–7097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:517–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTacchio L, Le HD, Vollmers C, Hatori M, Witcher M, Secombe J, Panda S. Histone lysine demethylase JARID1a activates CLOCK-BMAL1 and influences the circadian clock. Science. 2011;333:1881–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.1206022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan KL, Patel VR, Mohney RP, Vignola KS, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P. Coordination of the transcriptome and metabolome by the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5541–5546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118726109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegaray JP, Yang X, DeBruyne JP, Peters AH, Weaver DR, Jenuwein T, Reppert SM. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is required for mammalian circadian clock function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21209–21215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, Bugge A, Mullican SE, Alenghat T, Liu XS, Lazar MA. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari F, Gramantieri L, Ferracin M, Veronese A, Sabbioni S, Calin GA, Grazi GL, Giovannini C, Croce CM, Bolondi L, Negrini M. MiR-221 controls CDKN1C/p57 and CDKN1B/p27 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:5651–5661. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RJ, Olson EN. Control of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by the Let-7 family of microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:21075–21080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D, Le Martelot G, Vejnar CE, Gerlach D, Schaad O, Fleury-Olela F, Ruskeepaa AL, Oresic M, Esau CC, Zdobnov EM, Schibler U. Integration of microRNA miR-122 in hepatic circadian gene expression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1313–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.1781009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, Ditacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, Ellisman MH, Panda S. Time-Restricted Feeding without Reducing Caloric Intake Prevents Metabolic Diseases in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, DiTacchio L, Hayes KR, Vollmers C, Pulivarthy S, Baggs JE, Panda S, Hogenesch JB. Harmonics of circadian gene transcription in mammals. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005;309:1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangaspeska S, Stride B, Metivier R, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Ibberson D, Carmouche RP, Benes V, Gannon F, Reid G. Transient cyclical methylation of promoter DNA. Nature. 2008;452:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katada S, Sassone-Corsi P. The histone methyltransferase MLL1 permits the oscillation of circadian gene expression. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1414–1421. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike N, Yoo SH, Huang HC, Kumar V, Lee C, Kim TK, Takahashi JS. Transcriptional Architecture and Chromatin Landscape of the Core Circadian Clock in Mammals. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Crosthwaite SK. Role for antisense RNA in regulating circadian clock function in Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003;421:948–952. doi: 10.1038/nature01427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok RP, Lundblad JR, Chrivia JC, Richards JP, Bachinger HP, Brennan RG, Roberts SG, Green MR, Goodman RH. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature. 1994;370:223–226. doi: 10.1038/370223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Martelot G, Claudel T, Gatfield D, Schaad O, Kornmann B, Sasso GL, Moschetta A, Schibler U. REV-ERBalpha participates in circadian SREBP signaling and bile acid homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, O’Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, Gregory BD, Berry CC, Millar AH, Ecker JR. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo QM, Edsall L, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Stewart R, Ruotti V, Millar AH, Thomson JA, Ren B, Ecker JR. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, Hawkins RD, Nery JR, Hon G, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, O’Malley R, Castanon R, Klugman S, Downes M, Yu R, Stewart R, Ren B, Thomson JA, Evans RM, Ecker JR. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri S, Sassone-Corsi P. Plasticity and specificity of the circadian epigenome. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1324–1329. doi: 10.1038/nn.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Peron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, Ibberson D, Barath P, Demay F, Reid G, Benes V, Jeltsch A, Gannon F, Salbert G. Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F, Li Y, Shioda T, Cohen DE, Gerszten RE, Naar AM. MicroRNA-33 and the SREBP host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1566–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1189123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse Y, Oh-hashi K, Iijima N, Naruse M, Yoshioka H, Tanaka M. Circadian and light-induced transcription of clock gene Per1 depends on histone acetylation and deacetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6278–6287. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6278-6287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira CM, Rolo AP. Mitochondrially-mediated toxicity of bile acids. Toxicology. 2004;203:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos YF, Hestand MS, Verlaan M, Krabbendam E, Ariyurek Y, van Galen M, van Dam H, van Ommen GJ, den Dunnen JT, Zantema A, t Hoen PA. Genome-wide assessment of differential roles for p300 and CBP in transcription regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5396–5408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner KJ, Suarez Y, Davalos A, Parathath S, Fitzgerald ML, Tamehiro N, Fisher EA, Moore KJ, Fernandez-Hernando C. MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1189862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AB, O’Neill JS. Healthy clocks, healthy body, healthy mind. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey G, Cesbron F, Rougemont J, Reinke H, Brunner M, Naef F. Genome-wide and phase-specific DNA-binding rhythms of BMAL1 control circadian output functions in mouse liver. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripperger JA, Schibler U. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat Genet. 2006;38:369–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15782–15787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzenente B, Metodiev MD, Wredenberg A, Bratic A, Park CB, Camara Y, Milenkovic D, Zickermann V, Wibom R, Hultenby K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Brandt U, Stewart JB, Gustafsson CM, Larsson NG. LRPPRC is necessary for polyadenylation and coordination of translation of mitochondrial mRNAs. EMBO J. 2012;31:443–456. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straume M. DNA microarray time series analysis: automated statistical assessment of circadian rhythms in gene expression patterning. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:149–166. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovski M, Hausser J, Soutschek J, Bhat B, Akin A, Zavolan M, Heim MH, Stoffel M. MicroRNAs 103 and 107 regulate insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2011;474:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nature10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda HR, Chen W, Adachi A, Wakamatsu H, Hayashi S, Takasugi T, Nagano M, Nakahama K, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Iino M, Shigeyoshi Y, Hashimoto S. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature. 2002;418:534–539. doi: 10.1038/nature00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukai-Tadenuma M, Yamada RG, Xu H, Ripperger JA, Liu AC, Ueda HR. Delay in feedback repression by cryptochrome 1 is required for circadian clock function. Cell. 2011;144:268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide LP, Smidt MP. Regulation of FoxO activity by CBP/p300-mediated acetylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visel A, Blow MJ, Li Z, Zhang T, Akiyama JA, Holt A, Plajzer-Frick I, Shoukry M, Wright C, Chen F, Afzal V, Ren B, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature. 2009;457:854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature07730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmers C, Gill S, DiTacchio L, Pulivarthy SR, Le HD, Panda S. Time of feeding and the intrinsic circadian clock drive rhythms in hepatic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21453–21458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Peng W, Zhang MQ, Zhao K. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, Bookout AL, He W, Straume M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.