Abstract

Bordetella pertussis causes whooping cough, an infectious disease that is reemerging despite widespread vaccination. A more complete understanding of B. pertussis pathogenic mechanisms will involve unravelling the regulation of its impressive arsenal of virulence factors. Here we review the action of the B. pertussis response regulator BvgA in the context of what is known about bacterial RNA polymerase and various modes of transcription activation. At most virulence gene promoters, multiple dimers of phosphorylated BvgA (BvgA~P) bind upstream of the core promoter sequence, using a combination of high- and low-affinity sites that fill through cooperativity. Activation by BvgA~P is typically mediated by a novel form of class I/II mechanisms, but two virulence genes, fim2 and fim3, which encode serologically distinct fimbrial subunits, are regulated using a previously unrecognized RNA polymerase/activator architecture. In addition, the fim genes undergo phase variation because of an extended cytosine (C) tract within the promoter sequences that is subject to slipped-strand mispairing during replication. These sophisticated systems of regulation demonstrate one aspect whereby B. pertussis, which is highly clonal and lacks the extensive genetic diversity observed in many other bacterial pathogens, has been highly successful as an obligate human pathogen.

Introduction

Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough (pertussis), was first isolated from an infected person in 1906 (Bordet & Gengou, 1906). The small Gram-negative aerobic coccobacillus is an obligate human pathogen and thus has no known environmental reservoir. Vaccination programs have contributed to a substantial decrease in pertussis incidence, from ~260 000 cases in the USA in 1934 to ~1000 cases in 1976 (CDC, 1995). However, the increase in incidence since the early 1980s – including 27 550 cases in 2010 (CDC, 2011) – makes pertussis the most prevalent vaccine-preventable disease in industrialized countries (Mooi et al., 2009).

Whooping cough is resurging in countries with a historically low incidence attributable to high vaccine uptake (CDC, 1995; de Melker et al., 2000; Kerr & Matthews, 2000). The hallmark of this resurgence is a shift in prevalence from young children to adolescents and adults (discussed by Halperin, 2007). Multiple explanations have been offered for the reemergence of pertussis. These include an increased awareness of the disease, improved laboratory diagnostic tools, suboptimal vaccines and decreased vaccination coverage in parts of the world (Gangarosa et al., 1998).

At first glance, the persistence of pertussis despite intense vaccination efforts is unexpected because B. pertussis is highly clonal and lacks the genetic diversity of many other pathogens (Caro et al., 2006; Diavatopoulos et al., 2005; Parkhill et al., 2003; van Loo et al., 2002). Differences between B. pertussis clinical isolates are mainly due to differential expression of genes for surface-expressed proteins, mutations in genes for secreted proteins and gene reduction mediated by insertion sequence elements (Brinig et al., 2006; Caro et al., 2006; Heikkinen et al., 2007). In fact, among the major Bordetella subspecies, including Bordetella parapertussis, which causes a typically milder respiratory disease in humans, and Bordetella bronchiseptica, which infects many four-legged mammals, as well as B. pertussis, phenotypic differences have not been attributed to pathogenicity islands, plasmids, transposable elements or insertions from phage genomes. This finding distinguishes Bordetella from Salmonella and Vibrio species (reviewed by Cotter & DiRita, 2000). Thus, in Bordetella, the virulence regulon is differentially expressed in the different subspecies, yielding bacteria with very different niches and lifestyles (reviewed by Cotter & DiRita, 2000; Mattoo et al., 2001).

Effective pathogenesis involves tightly coordinated regulation of virulence factors in response to environmental cues (Dorman, 1995; Marteyn et al., 2010; Rhen & Dorman, 2005; Swanson & Hammer, 2000). For example, disturbing the usual pattern of virulence gene expression in Bordetella can significantly reduce colonization in a mouse model (Akerley et al., 1995; Kinnear et al., 2001). Furthermore, B. pertussis regulation employs a sophisticated repertoire to provide phenotypic diversity within highly clonal, genetically homogeneous bacterial populations. Hence, in addition to its role in global health and infectious disease, B. pertussis provides a valuable model in the laboratory to investigate regulation across all bacterial species. Here, we discuss regulation of the B. pertussis virulence genes, highlighting the promoters for fhaB, encoding filamentous haemagglutinin, and the fim genes, encoding fimbriae. We emphasize how the control of these genes differs from other well-characterized systems of bacterial activation and discuss the role of these regulatory mechanisms in the context of B. pertussis virulence.

The two-component system BvgAS regulates virulence genes in B. pertussis

To sense relevant cues in the external environment and transduce these signals into intracellular responses such as changes in gene expression, bacteria frequently utilize two-component systems. These systems typically consist of a sensor kinase (SK) and a response regulator (RR), which functions as a DNA-binding transcriptional activator (reviewed by Stock et al., 2000). The SK includes a sensing domain, situated in the bacterial periplasm, connected via a transmembrane segment to a kinase domain, located inside the cell. The SK is thought to transmit the signal to the cell interior via a conformational change within the protein, which affects the efficiency of ATP-dependent autophosphorylation of one SK molecule by its homodimer partner. However, the exact molecular mechanism remains elusive. The RR activator then catalyses its own phosphorylation with the phosphate group donated by its cognate SK or by a small molecule phosphodonor (acetyl phosphate, imidazole phosphate or phosphoramidate, among others). Because these signalling mechanisms are quite rare in eukaryotes (Galperin, 2010), two-component systems are potential targets for antimicrobial therapies.

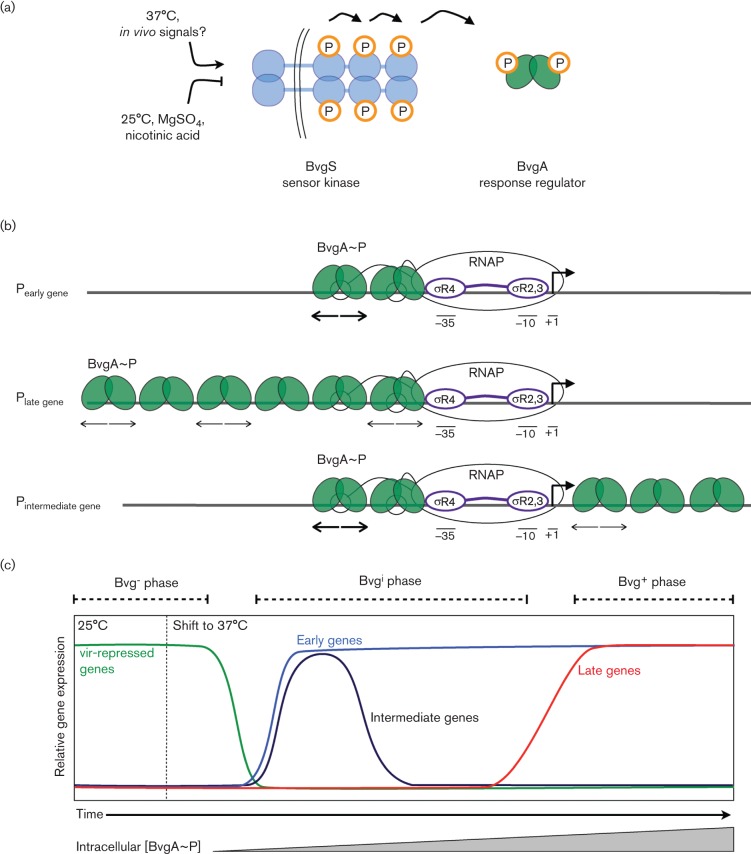

In the genus Bordetella, the primary two-component system involved in virulence gene regulation consists of the sensor kinase BvgS and the response regulator BvgA. BvgS is a ‘hybrid’ SK, which has three phosphorylation sites in three distinct domains that mediate a phosphorelay (Fig. 1a) (Uhl & Miller, 1996). Phosphorylated BvgA (BvgA~P) binds to different virulence gene promoters in different binding patterns, discussed below, to activate transcription. BvgAS controls the expression of over 100 virulence genes (Bootsma et al., 2002) and the BvgS and BvgA sequences are almost invariant among B. pertussis strains and clinical isolates (Herrou et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

The BvgAS system and temporal gene regulation. (a) The BvgS sensor kinase is anchored in the inner membrane. Activating signals trigger BvgS autophosphorylation, initiating a phosphorelay that results in phosphorylation of the BvgA response regulator. (b) Phosphorylated BvgA (BvgA~P) binds to virulence gene promoters to regulate activity. BvgA binding sites are marked with inverted arrows (thick lines, high-affinity sites; thin lines, low-affinity sites). At those promoters where the αCTD subunit positions have been identified, αCTD binds to the same region of DNA as the promoter-proximal BvgA~P dimers (Boucher et al., 2003; Decker et al., 2011). (c) Schematic illustrating temporal gene regulation by BvgAS. BvgA~P activates its own expression, so intracellular BvgA~P concentration increases with time at 37 °C (x-axis labels). The Bvg− phase is characterized by expression of the vir-repressed genes; Bvgi by expression of the early and intermediate genes; Bvg+ by expression of the early and late genes, whose products are required for virulence.

In 1960, Lacey reported different antigenic properties for three distinct modes of B. pertussis and chose the term ‘modulation’ to describe the transition between modes (Lacey, 1960). Today, we understand that the three modes described by Lacey correspond to what are now known as the Bvg+, Bvg− and Bvgi (intermediate) phases (Fig. 1c). The Bvg+ phase, characterized by expression of all BvgA-activated adhesins and toxins, is required for virulence (Cotter & Miller, 1994). This phase is manifested under ‘non-modulating’ environmental conditions that are conducive to phosphorylation of BvgS, such as growth near 37 °C, the temperature in the respiratory tract of the human host. The Bvgi phase, in which the BvgAS system is not fully induced, may have a role in transmission by aerosol route or the initial stages of infection.

‘Modulating’ conditions [growth at lower temperatures (25 °C) or the presence of nicotinic acid or magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) in the growth medium] result in a reduction of BvgS activity, leading to the Bvg− phase. The role of the Bvg− phase is not yet understood, but it is clearly not required for virulence in animal models of infection (García San Miguel et al., 1998). However, inappropriate expression of the Bvg− phase in vivo is actually detrimental to successful infection (Merkel et al., 1998). It has been hypothesized to be important for intracellular uptake and persistence, or transmission between mammalian hosts (Herrou et al., 2009; Locht et al., 2001). In B. bronchiseptica, the Bvg− phase is adapted for survival under conditions of extreme nutrient deprivation (Cotter & Miller, 1994). Alternatively, it may be an evolutionary remnant from an ancestor that occupied an environmental niche (Gerlach et al., 2001; von Wintzingerode et al., 2001).

Temporal gene regulation by BvgA~P coordinates the expression of proteins needed for virulence

The differential binding to the regulatory regions of different virulence genes constitutes a simple yet highly effective system by which regulation by BvgA~P can result in varied kinetics of virulence factor expression. Virulence genes whose products are presumably involved early in pathogenesis – such as surface-expressed adhesin proteins and BvgA itself – are activated almost immediately upon a shift to permissive growth conditions (37 °C) (Scarlato et al., 1991) (Fig. 1c). This rapid transcriptional response is thought to arise from the presence of high-affinity BvgA~P binding sites located upstream of the early virulence gene promoters (Fig. 1b).

Virulence genes whose products are thought to play a role later in pathogenesis – such as toxins and their secretion systems – remain transcriptionally inactive until the intracellular concentration of BvgA~P increases to a level sufficient to fill the low-affinity BvgA~P sites upstream of the late virulence gene promoters (discussed by Cotter & Jones, 2003) (Fig. 1b, c). In addition, an intermediate gene has been described (bipA) in which moderate levels of BvgA~P activate expression, but high levels repress expression (Williams et al., 2005) (Fig. 1b, c). Furthermore, BvgA acts indirectly as a negative effector through its regulation of the BvgR protein, which negatively regulates a set of genes encoding outer membrane and secreted proteins (Merkel et al., 2003).

The B. pertussis σ factor is an essential component of the transcription machinery

B. pertussis RNA polymerase (RNAP), like that of other bacteria, consists of an enzymic core (α1α2ββ′ω) plus a σ factor required to direct core to the promoter region at the start of a gene. Bacteria typically have multiple σ factors, which direct RNAP to different classes of genes based on the cell's needs (reviewed by Gruber & Gross, 2003).

In primary σ factors, which are responsible for most transcription during exponential growth, four conserved regions (regions 1–4) mediate interactions between σ and the core and/or promoter specificity (reviewed by Hook-Barnard & Hinton, 2007). Regions 2, 3 and 4 bind to specific recognition sites in the promoter DNA: the −10 element (–12TATAAT–7), an extended –10 element (–15TG–14) and the −35 element (–35TTGACA–30), respectively. Typically, two out of three such sequence elements are sufficient for recognition. In addition, the α subunit C-terminal domains (αCTDs) may also directly contact the DNA through AT-rich ‘UP’ elements, usually located between –40 and –60.

In B. pertussis, the primary σ is termed σ80. Its counterpart in Escherichia coli is the well-studied σ70. σ80 is 71 % similar and 55 % identical to E. coli σ70, and it has been shown that several known promoters are active using RNAP reconstituted with either σ factor (Baxter et al., 2006; Boucher et al., 1997; Decker et al., 2011; Steffen & Ullmann, 1998). Furthermore, within σ region 4, a portion of σ known to play a major role in gene regulation, σ70 and σ80 are 84 % similar and 73 % identical. Thus, it is reasonable to extrapolate much of the detailed characterization of σ70 to σ80.

One discrepancy between E. coli σ70 and B. pertussis σ80 resides in the N-terminal region where σ80 has a positively charged ‘region P’ (residues 1 to ~150). Such a domain is present in many pathogenic bacteria but absent in E. coli σ70 (Yang et al., 2010). In Helicobacter pylori, region P binds polyphosphate under conditions of limited nutrients, and mutations that eliminate this interaction lead to accelerated cell death during starvation. However, how and if this binding regulates gene expression is not yet known.

Bacterial transcription activation occurs through a variety of mechanisms

A promoter with ‘perfect’ elements does not equal a perfect promoter; such a construct cannot be regulated and, therefore, could be detrimental to an adaptive organism. Consequently, regulated promoters, such as those that drive expression of B. pertussis virulence genes, contain a complement of core promoter sequence elements that is suboptimal and then use DNA-binding factors to activate RNAP under the appropriate conditions.

Transcription initiation proceeds through multiple steps (Kontur et al., 2008; Saecker et al., 2002; reviewed by Hook-Barnard & Hinton, 2007), from an initial closed complex (RPC), in which the DNA is fully double-stranded, to an open complex (RPO), in which polymerase has isomerized and the DNA has bent, opened and descended into the active site (Gries et al., 2010). Consequently, there are multiple points at which an activator might function. Several classes of activators, distinguished by their varying mechanisms, have been described.

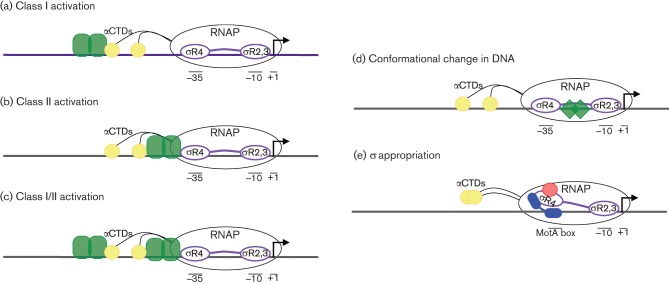

Bacterial class I activators bind to promoter DNA upstream of the –35 element (typically near –60) and directly interact with the RNAP αCTDs (Fig. 2a). It is thought that this interaction, by stimulating initial binding of RNAP, helps to recruit the enzyme to the promoter (reviewed by Gourse et al., 2000). In contrast, class II activators bind to promoter DNA adjacent to or overlapping the –35 element (Fig. 2b). At this location, they are positioned to interact with the DNA-recognition helix within σ70 region 4 and/or α subunits CTDs or NTDs (Dove et al., 2003). These activators can also help recruitment and/or accelerate rate-limiting steps in the formation of RPO (Barnard et al., 2004; Browning & Busby, 2004; Lawson et al., 2004). Interestingly, among class II activators, there is variation in the precise binding site and orientation of the activator, discussed below. In addition, some promoters use a combination of class I and class II (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Characterized mechanisms of prokaryotic gene activation. Purple, σ; yellow, αCTD; green, specified activator. (a) Class I activators bind upstream of the core promoter elements and interact with the RNAP αCTD subunit(s). (b) Class II activators bind closer to the core promoter elements, adjacent to or overlapping the −35 element, and interact with σ region 4 and/or αCTD. (c) Combination class I/II activation relies on independent interactions between an upstream activator and αCTD, and a downstream activator and σ region 4 and/or αCTD. (d) The MerR activator causes a conformational change in the alignment of the −10 and −35 elements that allows promoter recognition and gene activation. (e) During activation by σ appropriation, bacteriophage T4 proteins AsiA (red) and MotA (blue) interact with σ70 region 4 to redirect RNAP from host E. coli promoters to T4 middle promoters, which contain a MotA box sequence centred at −30.

Mechanisms of some other transcription factors bear little resemblance to class I or class II activation. For example, MerR activates expression of the mercuric ion operons by binding to the unusually long spacer region between the –10 and –35 core promoter elements (Fig. 2d). Its binding contorts the DNA, effectively shortening the spacer and creating a functional promoter for RNAP (Hobman et al., 2005; Watanabe et al., 2008).

Another differing mechanism is σ appropriation, by which a class of bacteriophage T4 promoters are activated and host promoters are silenced (reviewed by Hinton, 2010). In this system, a small T4 protein, AsiA, binds tightly to E. coli σ70 region 4 and structurally remodels it to preclude binding to the –35 element of E. coli promoters (Fig. 2e) (Lambert et al., 2004). The remodelled σ factor is correctly positioned to interact with another T4 protein, MotA, which redirects transcription activity to T4’s own middle promoters via recognition of a specific site at –30. Thus, this system works by replacing σ region 4 specificity for one sequence with the activator’s specificity for a different sequence.

BvgA~P-regulated promoters have a characteristic architecture

At typical B. pertussis early promoters, such as those for the genes fha and bipA, a head-to-head dimer of BvgA~P binds to a primary binding site [inverted heptads with consensus sequence (T/A)TTC(C/T)TA typically located ≥60 base pairs upstream of a virulence gene promoter; Fig. 1b; Boucher et al., 1997; Roy & Falkow, 1991], and additional dimers of BvgA~P bind to adjacent, secondary binding sites in a cooperative manner that can be relatively independent of the DNA sequence (Boucher & Stibitz, 1995; Boucher et al., 2001; Marques & Carbonetti, 1997). Other promoters, such as the late promoters driving ptx and cya expression, utilize a consortium of binding sites with poorer matches to the consensus sequence. These sites, acting cooperatively, are filled and stimulate transcription only at higher intracellular concentrations of BvgA~P.

A structure of BvgA has not yet been obtained. Consequently, the DNA-binding domain of BvgA has been conventionally modelled on the response regulator NarL because of the sequence similarity between the two proteins (Boucher et al., 2003). The binding behaviour of BvgA has been revealed by studies using BvgA~P modified at single residues with the cleavage reagent Fe-BABE (Boucher et al., 2003). The details of this binding are entirely consistent with the X-ray crystal structure of NarL bound to its DNA site (Proulx et al., 2002). However, the activity of BvgA seems to differ from that of NarL. For example, NarL does not detectably bind DNA unless it is phosphorylated (Proulx et al., 2002). In contrast, unphosphorylated BvgA has been shown to bind DNA (Boucher et al., 1994, 1997; Karimova et al., 1996; Zu et al., 1996; K. B. Decker, unpublished data). In addition, BvgA~P binds to virulence gene promoters with greater affinity and in at least one case, in a different binding pattern than does BvgA (Boucher et al., 1994, 1997; Boucher & Stibitz, 1995; Karimova et al., 1996; Steffen et al., 1996; Zu et al., 1996; K. B. Decker, unpublished data).

For most of the B. pertussis virulence gene promoters, the binding site for the downstream-most BvgA~P dimer is located near the –35 region of the promoter, in a position to interact with σ and/or αCTD, as in class II activation, while the upstream binding sites could interact with the other αCTD, as in class I (Boucher & Stibitz, 1995; Boucher et al., 1997, 2001; Karimova et al., 1996; Karimova & Ullmann, 1997; Kinnear et al., 1999; Merkel et al., 2003; Zu et al., 1996). Consistent with a combination class I/II mechanism (Fig. 2c), BvgA~P activation at PfhaB requires residues within αCTD (Boucher et al., 1997) and σ region 4 (Decker et al., 2011).

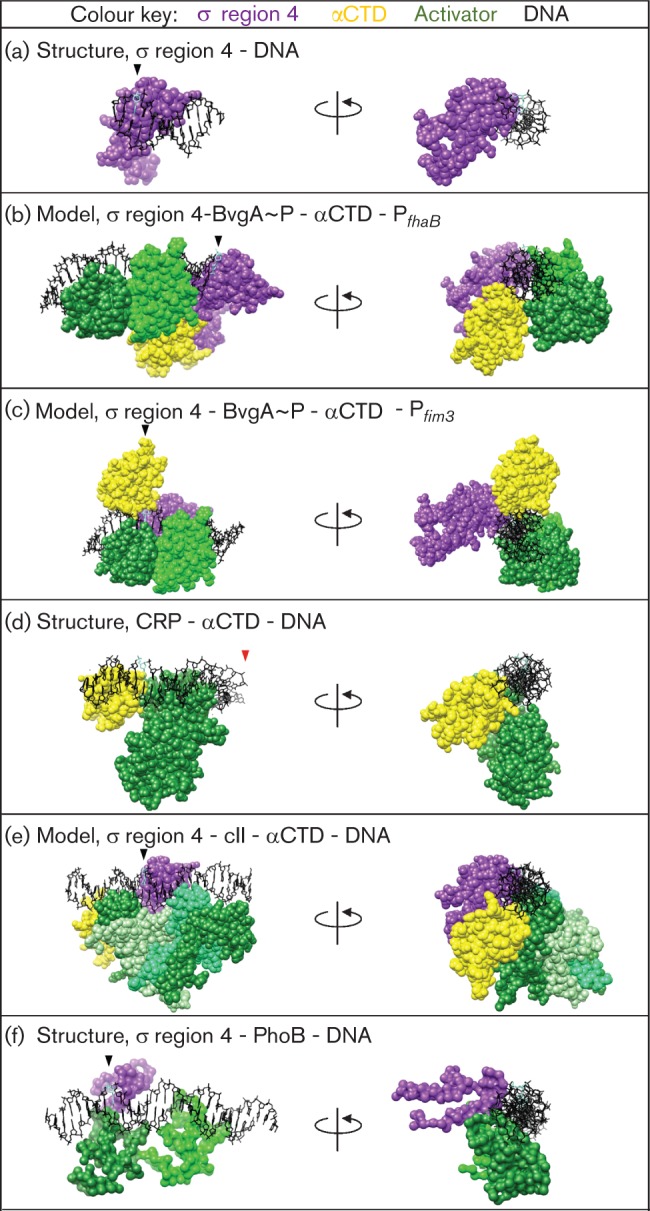

Despite these similarities with class I/II promoters, the architecture of RNAP/BvgA~P at PfhaB is not like other characterized class II activators. The molecular structures and models in Fig. 3 illustrate this point. The left panels in Fig. 3(b–f) depict activator/αCTD/σ region 4 complexes along the promoter DNA (upstream to downstream) whereas the right panels depict an end-on view, in which σ region 4 (when shown) is kept in the same orientation. In Fig. 3(a), σ region 4 can be seen at the −35 element of host promoter DNA. For the promoters at which region 4 is shown, this position remains generally the same, positioned at the −35 region of the promoter (compare the purple region 4 in the right panels).

Fig. 3.

The protein conformation at BvgA~P-activated Pfim3 differs from that at characterized class II promoters. Purple, σ region 4; yellow, αCTD; green, specified activator. For (a)–(c) and (e)–(f), the −35 nontemplate strand nucleotide (nt) is shaded cyan and marked with a carat (left panel) and oriented in the 12 o’clock position (as viewed in the right panel). For (d), the −56 nontemplate strand nt is shaded cyan and oriented in the 12 o’clock position; because the −56 nt is ~two helical turns upstream from the −35 nt in B-form DNA, the complex in (d) is similarly oriented to (a)–(c) and (e)–(f). The red carat in (d) marks nt position −41.5. (a) σ Region 4 bound to −35 region DNA, as a reference for (b)–(f) (Campbell et al., 2002); PDB no. 1KU7. (b) BvgA~P activation at PfhaB: σ region 4, αCTD, BvgA~P dimer bound to its promoter-proximal site; modelled on the work of Boucher et al. (2003). (c) BvgA~P activation at Pfim3: σ region 4, αCTD, BvgA~P dimer bound to its promoter proximal site, overlapping the −35 region DNA; modelled on work of Decker et al. (2011). (d) Class II activation by CRP at galP1: a dimer of CRP centred at −41.5 interacts with an upstream-bound αCTD. Only the upstream monomer of CRP is shown; σ region 4 is not shown as it was not part of the crystallized complex. Structure taken from Benoff et al. (2002); PDB no. 1LB2. (e) Class II activation by cII at PRE: σ region 4 (aa 461–599), αCTD, cII tetramer. Model from Jain et al. (2005; gift from S. Darst, Rockefeller University). (f) Class II activation by PhoB at PpstS: σ region 4 (aa 533–613), PhoB dimer. The β-flap tip helix, crystallized as a chimera with σ region 4, is not shown. Structure from Blanco et al. (2011); PDB no. 3T72.

In contrast, the relative positions of αCTD and the activator are not constant at these various promoters. At PfhaB (Fig. 3b), each α contacts the same region of DNA as a BvgA dimer, but on a different helical face (Boucher et al., 2003). This is unlike previously characterized class I/II systems (reviewed by Barnard et al., 2004), such as the CRP dimer/αCTD/galP1 structure (Fig. 3d) (Benoff et al., 2002) or the modelled structure of λ cII dimer/σ region 4/αCTD/PRE (Fig. 3e) (Jain et al., 2005), in which the activator and αCTD are adjacent to one another (compare the different locations of the yellow αCTD at PfhaB in the left panel of Fig. 3b versus its locations in the left panels of Fig. 3d and e). Thus, the RNAP/BvgA~P complex at PfhaB represents a new twist on class I/II activation. Furthermore, as discussed in detail below, recent evidence indicates that BvgA~P activation at the promoters for the fim genes (Pfim2 and Pfim3) involves an even more radical departure from the typical class II architecture.

The requirements for BvgA~P activation seem to involve more than just proximity between activator and polymerase. The positions of the proteins around the faces of the DNA double-helix also appear to be important. DNA mutations that disrupt the pattern of multiple sites along one face of the DNA double-helix are deleterious to promoter activity. However, mutations which remove an entire binding site yet maintain the dimer positions still allow promoter activity (Boucher et al., 2001; Marques & Carbonetti, 1997). The orientation of BvgA~P dimers along the same face of the double-helix may be important for cooperative binding of activators to the promoter or for the correct BvgA~P-RNAP interaction. Consistent with this idea is the effect of different lengths of homopolymeric tracts in the promoter regions of the fim genes, described below. Changing the lengths of these promoter regions, which alters the spacing between promoter elements as well as relative orientation of one bound protein to another around the double-helix, has dramatic effects on promoter activity (Chen et al., 2010; Riboli et al., 1991; Willems et al., 1990).

Phase variation in the fim genes generates phenotypic diversity within a population

The fim promoters are emerging as instructive models for multiple levels of gene regulation that together create a fine-tuned response to the environment and ensure the success of a multicellular population. fim2 and fim3 encode subunits of the long serrated fimbriae, serotypes 2 and 3, respectively (Heck et al., 1996; Mooi et al., 1987). Fimbriae (also called pili) allow B. pertussis to adhere to host cells and are required for efficient establishment of tracheal colonization and persistence in mouse and rat models (Geuijen et al., 1997; Mooi et al., 1992).

Expression of the fim genes is regulated at multiple levels – as part of the BvgAS regulon and at the level of the individual gene through phase variation (Heikkinen et al., 2008; Willems et al., 1990). Phase variation is a phenomenon that allows expression of a given factor to switch between ‘on’ or ‘off’ states at a rate greater than that of random mutation, frequently affecting fimbriae, flagella, outer-membrane proteins and lipopolysaccharide components in Gram-negative bacteria (reviewed by Dybvig, 1993; Henderson et al., 1999). Phase variation can occur by DNA inversion, recombination, differential methylation or, as in the case of the fim genes, by slipped-strand mispairing resulting in alteration of the length of a repetitive sequence in the regulatory or coding regions of a gene (Seifert & So, 1988; Streisinger & Owen, 1985).

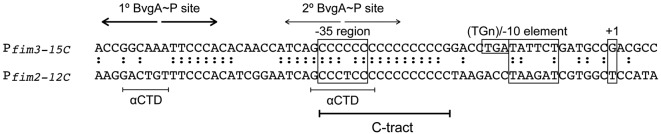

The fim2 and fim3 promoters each contain a homopolymeric tract of cytosines (‘C-tract’) overlapping the −35 region, and each promoter can be activated by BvgA~P only when the C-tract is of a permissive length (Fig. 4) (Chen et al., 2010; Willems et al., 1990). This tract does not contain sequence-specific information, but instead appears to function as a spacer between transcription activation machinery bound to different elements of the promoter (Chen et al., 2010). Because C-tract regulation of one fim promoter operates independently from the other, cells can express any combination of fim proteins on their surface, contributing to phenotypic diversity within a population. Interestingly, a B. pertussis gene with sequence homology to fim3 and fim2 has an extremely truncated promoter C-tract: 7 Cs compared with 15 Cs in the active form of fim3. This gene, called fimX, appears to be transcriptionally silent due to the deletion in the C-tract (Chen et al., 2010; Willems et al., 1990). Moreover, the shorter homopolymeric tract limits the amount of slipped-strand mispairing that is likely to occur, making a reversion to activity by addition of Cs highly improbable. Why B. pertussis has maintained an intact copy of this supposedly ‘silent’ gene remains unclear.

Fig. 4.

Promoter architecture of Pfim3 and Pfim2. The –35 region, extended –10 (TGn) element, –10 element and +1 transcription start site are outlined in boxes. BvgA~P binding sites are marked with inverted arrows: thick line, higher-affinity primary site; thin line, lower-affinity secondary site (Chen et al., 2010). The positions at which the αCTD subunits are observed to bind at Pfim3 are marked (Decker et al., 2011). The C-tract, which can vary in length in each promoter, is marked. Sequence identity between fim paralogues is marked with two dots.

Phase variation by slipped-strand mispairing can be considered a ‘programmed’ random event: the insertion or deletion of nucleotides is stochastic, but the frequency with which it occurs increases for homopolymeric tracts of increasing length (Streisinger & Owen, 1985). One benefit of phase variation is that it allows an organism to create diversity in an otherwise clonal population – a valuable trait for B. pertussis which has unusually poor genomic diversity for a pathogen (Gogol et al., 2007). Phenotypic diversity among surface-exposed adhesins is no doubt important for evading the host surveillance system and may be important to ensure some bacteria are poised to move to a new environment through detachment and shedding (Dybvig, 1993; Henderson et al., 1999).

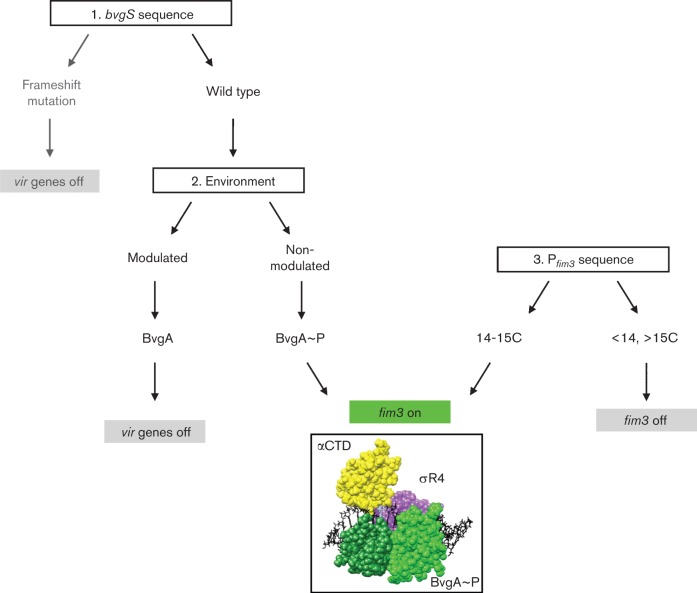

Notably, the bvgS open reading frame also contains a C-tract, which is susceptible in certain strain backgrounds to slipped-strand mispairing during replication (Levinson & Gutman, 1987); insertion or deletion of a C yields a truncated, nonfunctional BvgS protein (Stibitz et al., 1989). As a result, virulence genes that are normally activated by the BvgAS system are not expressed, rendering them avirulent (Stibitz et al., 1989). However, the biological relevance of this system during an infection is not known.

The molecular mechanism of fim activation is complex and elegant

Besides the ability to undergo phase variation, the fim promoters are unusual because the position of the downstream BvgA~P binding site surrounds the −35 region of the promoter DNA (Chen et al., 2010) (Fig. 4). Recent work has sought to define the interaction between the activators and RNAP within this unusual architecture (Decker et al., 2011). Surprisingly, although σ region 4 is not required for BvgA~P activation of Pfim3, it is still located on or near its usual position at the –35 region of Pfim3, despite the fact that this region consists of the monotonic C-tract. In addition, the αCTD subunits of RNAP bind to the same regions of the DNA as the BvgA~P dimers, and in the same configuration relative to BvgA as shown for PfhaB. This arrangement places σ region 4, one αCTD and a BvgA~P dimer at the −35 region of Pfim3, suggesting that the proteins bind to different faces of the same stretch of promoter DNA.

A speculative model of the protein arrangement at Pfim3 consists of the three subunits arranged around the DNA double helix in a conformation that likely depends on specific protein–protein interactions, since the DNA lacks specific sequence information to direct the protein position (Decker et al., 2011) (Fig. 3c). This model explains the exquisite control over regulation by the length of the C-tract. The insertion or deletion of one C would alter the orientation of the protein subunits around the double helix and thus should disrupt the correct positioning needed for activation.

The protein arrangement in BvgA~P activation of the fim3 promoter offers an architecture that differs even more dramatically from that seen at typical class II promoters, or even at PfhaB. This is because the αCTD within the −35 region of Pfim3 is positioned nearly a helical turn farther downstream than has been seen previously. Furthermore, for class II activators like CRP at galP1 (Fig. 3d) (Benoff et al., 2002) or PhoB at pho box DNA (Fig. 3f) (Blanco et al., 2011), the activator is poised to interact with a common set of region 4 residues (discussed by Bonocora et al., 2008). However, the particular positioning of BvgA~P at Pfim3 means that these residues are not available for a region 4/activator interaction. Finally, despite the fact that the BvgA~P site includes the −35 region for the promoter, just as the binding site of the T4 MotA activator includes this portion of the DNA, the fim promoter activation complex is completely different from that formed by σ region 4 with the bacteriophage T4 proteins AsiA and MotA (reviewed by Hinton, 2010). Thus, activation at the fim promoters provides another example of how σ region 4 can be utilized in an activation system.

Conclusions

A mechanistic understanding of the activation of B. pertussis virulence genes is vital given the reemergence of the pathogen and the fact that some acellular vaccines directly and exclusively target virulence factors of the bacterium, including Fim2 and Fim3 (Bouchez et al., 2008, 2009; Geier & Geier, 2002). In addition, evidence from clinical studies may suggest that the Fim antigens are perhaps being subjected to immune selection due to vaccine-induced and natural-antibody-driven adaptation (Gogol et al., 2007; Tsang et al., 2004). The sophisticated controls used by B. pertussis to regulate virulence genes (differential binding of the BvgA~P activator to the promoters, different RNAP/activator architectures and phase variation by programmed mutation) demonstrate how a pathogen that is highly clonal and lacks the genetic diversity of many other pathogens can be quite successful as an obligate human pathogen (Fig. 5). A more complete understanding of the virulence factors and their regulation, and the host immune response is essential to develop the next generation of pertussis vaccines and treatments.

Fig. 5.

Multiple independent regulatory mechanisms ensure appropriate virulence gene expression and create phenotypic diversity in a Bordetella population. The bvgS sequence, environmental temperature and the length of the fim promoter C-tract together determine fim activity. Modulating conditions include lower temperature (25 °C) or the presence of MgSO4 or nicotinic acid; non-modulating conditions include growth at 37 °C. How frameshifting within bvgS contributes to pertussis infection is not clear.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen Usdin, Saheli Jha, Alice Boulanger-Castaing and Leslie Knipling (NIDDK, NIH) for helpful discussions and especially Seth Darst (Rockerfeller University) for sharing the modelled structure of cII/σ region 4/αCTD at PRE. Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

References

- Akerley B. J., Cotter P. A., Miller J. F. (1995). Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella–host interaction. Cell 80, 611–620. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard A., Wolfe A., Busby S. (2004). Regulation at complex bacterial promoters: how bacteria use different promoter organizations to produce different regulatory outcomes. Curr Opin Microbiol 7, 102–108. 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter K., Lee J., Minakhin L., Severinov K., Hinton D. M. (2006). Mutational analysis of sigma70 region 4 needed for appropriation by the bacteriophage T4 transcription factors AsiA and MotA. J Mol Biol 363, 931–944. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoff B., Yang H., Lawson C. L., Parkinson G., Liu J., Blatter E., Ebright Y. W., Berman H. M., Ebright R. H. (2002). Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP-alpha CTD-DNA complex. Science 297, 1562–1566. 10.1126/science.1076376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco A. G., Canals A., Bernués J., Solà M., Coll M. (2011). The structure of a transcription activation subcomplex reveals how σ70 is recruited to PhoB promoters. EMBO J 30, 3776–3785. 10.1038/emboj.2011.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonocora R. P., Caignan G., Woodrell C., Werner M. H., Hinton D. M. (2008). A basic/hydrophobic cleft of the T4 activator MotA interacts with the C-terminus of E. coli sigma70 to activate middle gene transcription. Mol Microbiol 69, 331–343. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06276.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsma H. J., Cummings C. A., Relman D. A., Miller J. F. (2002). Global expression analysis of the Bordetella virulence regulon. National Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 102, abstract 1572. [Google Scholar]

- Bordet J., Gengou O. (1906). Le microbe de la coqueluche. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 20, 731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P. E., Stibitz S. (1995). Synergistic binding of RNA polymerase and BvgA phosphate to the pertussis toxin promoter of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 177, 6486–6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P. E., Menozzi F. D., Locht C. (1994). The modular architecture of bacterial response regulators. Insights into the activation mechanism of the BvgA transactivator of Bordetella pertussis. J Mol Biol 241, 363–377. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P. E., Murakami K., Ishihama A., Stibitz S. (1997). Nature of DNA binding and RNA polymerase interaction of the Bordetella pertussis BvgA transcriptional activator at the fha promoter. J Bacteriol 179, 1755–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P. E., Yang M. S., Schmidt D. M., Stibitz S. (2001). Genetic and biochemical analyses of BvgA interaction with the secondary binding region of the fha promoter of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 183, 536–544. 10.1128/JB.183.2.536-544.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P. E., Maris A. E., Yang M. S., Stibitz S. (2003). The response regulator BvgA and RNA polymerase alpha subunit C-terminal domain bind simultaneously to different faces of the same segment of promoter DNA. Mol Cell 11, 163–173. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchez V., Caro V., Levillain E., Guigon G., Guiso N. (2008). Genomic content of Bordetella pertussis clinical isolates circulating in areas of intensive children vaccination. PLoS ONE 3, e2437. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchez V., Brun D., Cantinelli T., Dore G., Njamkepo E., Guiso N. (2009). First report and detailed characterization of B. pertussis isolates not expressing Pertussis Toxin or Pertactin. Vaccine 27, 6034–6041. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinig M. M., Cummings C. A., Sanden G. N., Stefanelli P., Lawrence A., Relman D. A. (2006). Significant gene order and expression differences in Bordetella pertussis despite limited gene content variation. J Bacteriol 188, 2375–2382. 10.1128/JB.188.7.2375-2382.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D. F., Busby S. J. (2004). The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2, 57–65. 10.1038/nrmicro787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E. A., Muzzin O., Chlenov M., Sun J. L., Olson C. A., Weinman O., Trester-Zedlitz M. L., Darst S. A. (2002). Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol Cell 9, 527–539. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00470-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro V., Hot D., Guigon G., Hubans C., Arrivé M., Soubigou G., Renauld-Mongénie G., Antoine R., Locht C., et al. (2006). Temporal analysis of French Bordetella pertussis isolates by comparative whole-genome hybridization. Microbes Infect 8, 2228–2235. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (1995). Pertussis–United States, January 1992–June 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 44, 525–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2011). Pertussis (Whooping Cough). Outbreaks. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pert.html [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Decker K. B., Boucher P. E., Hinton D., Stibitz S. (2010). Novel architectural features of Bordetella pertussis fimbrial subunit promoters and their activation by the global virulence regulator BvgA. Mol Microbiol 77, 1326–1340. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07293.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter P. A., DiRita V. J. (2000). Bacterial virulence gene regulation: an evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 54, 519–565. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter P. A., Jones A. M. (2003). Phosphorelay control of virulence gene expression in Bordetella. Trends Microbiol 11, 367–373. 10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00156-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter P. A., Miller J. F. (1994). BvgAS-mediated signal transduction: analysis of phase-locked regulatory mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica in a rabbit model. Infect Immun 62, 3381–3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melker H. E., Schellekens J. F. P., Neppelenbroek S. E., Mooi F. R., Rümke H. C., Conyn-van Spaendonck M. A. E. (2000). Reemergence of pertussis in the highly vaccinated population of the Netherlands: observations on surveillance data. Emerg Infect Dis 6, 348–357. 10.3201/eid0604.000404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. B., Chen Q., Hsieh M. L., Boucher P., Stibitz S., Hinton D. M. (2011). Different requirements for σ Region 4 in BvgA activation of the Bordetella pertussis promoters P(fim3) and P(fhaB). J Mol Biol 409, 692–709. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diavatopoulos D. A., Cummings C. A., Schouls L. M., Brinig M. M., Relman D. A., Mooi F. R. (2005). Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS Pathog 1, e45. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J. (1995). 1995 Fleming Lecture. DNA topology and the global control of bacterial gene expression: implications for the regulation of virulence gene expression. Microbiology 141, 1271–1280. 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove S. L., Darst S. A., Hochschild A. (2003). Region 4 of sigma as a target for transcription regulation. Mol Microbiol 48, 863–874. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K. (1993). DNA rearrangements and phenotypic switching in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol 10, 465–471. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin M. Y. (2010). Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol 13, 150–159. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangarosa E. J., Galazka A. M., Wolfe C. R., Phillips L. M., Gangarosa R. E., Miller E., Chen R. T. (1998). Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story. Lancet 351, 356–361. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04334-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García San Miguel L., Quereda C., Martínez M., Martín-Dávila P., Cobo J., Guerrero A. (1998). Bordetella bronchiseptica cavitary pneumonia in a patient with AIDS. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 17, 675–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier D., Geier M. (2002). The true story of pertussis vaccination: a sordid legacy? J Hist Med Allied Sci 57, 249–284. 10.1093/jhmas/57.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach G., von Wintzingerode F., Middendorf B., Gross R. (2001). Evolutionary trends in the genus Bordetella. Microbes Infect 3, 61–72. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01353-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuijen C. A., Willems R. J., Bongaerts M., Top J., Gielen H., Mooi F. R. (1997). Role of the Bordetella pertussis minor fimbrial subunit, FimD, in colonization of the mouse respiratory tract. Infect Immun 65, 4222–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogol E. B., Cummings C. A., Burns R. C., Relman D. A. (2007). Phase variation and microevolution at homopolymeric tracts in Bordetella pertussis. BMC Genomics 8, 122. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourse R. L., Ross W., Gaal T. (2000). UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: the role of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol Microbiol 37, 687–695. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gries T. J., Kontur W. S., Capp M. W., Saecker R. M., Record M. T., Jr (2010). One-step DNA melting in the RNA polymerase cleft opens the initiation bubble to form an unstable open complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 10418–10423. 10.1073/pnas.1000967107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T. M., Gross C. A. (2003). Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu Rev Microbiol 57, 441–466. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin S. A. (2007). The control of pertussis–2007 and beyond. N Engl J Med 356, 110–113. 10.1056/NEJMp068288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck D. V., Trus B. L., Steven A. C. (1996). Three-dimensional structure of Bordetella pertussis fimbriae. J Struct Biol 116, 264–269. 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen E., Kallonen T., Saarinen L., Sara R., King A. J., Mooi F. R., Soini J. T., Mertsola J., He Q. S. (2007). Comparative genomics of Bordetella pertussis reveals progressive gene loss in Finnish strains. PLoS ONE 2, e904. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen E., Xing D. K., Olander R. M., Hytönen J., Viljanen M. K., Mertsola J., He Q. (2008). Bordetella pertussis isolates in Finland: serotype and fimbrial expression. BMC Microbiol 8, 162. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R., Owen P., Nataro J. P. (1999). Molecular switches – the ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol Microbiol 33, 919–932. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrou J., Debrie A. S., Willery E., Renauld-Mongénie G., Locht C., Mooi F., Jacob-Dubuisson F., Antoine R. (2009). Molecular evolution of the two-component system BvgAS involved in virulence regulation in Bordetella. PLoS ONE 4, e6996. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D. M. (2010). Transcriptional control in the prereplicative phase of T4 development. Virol J 7, 289. 10.1186/1743-422X-7-289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobman J. L., Wilkie J., Brown N. L. (2005). A design for life: prokaryotic metal-binding MerR family regulators. Biometals 18, 429–436. 10.1007/s10534-005-3717-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook-Barnard I. G., Hinton D. M. (2007). Transcription initiation by mix and match elements: flexibility for polymerase binding to bacterial promoters. Gene Regul Syst Bio 1, 275–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D., Kim Y., Maxwell K. L., Beasley S., Zhang R., Gussin G. N., Edwards A. M., Darst S. A. (2005). Crystal structure of bacteriophage lambda cII and its DNA complex. Mol Cell 19, 259–269. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G., Ullmann A. (1997). Characterization of DNA binding sites for the BvgA protein of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 179, 3790–3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G., Bellalou J., Ullmann A. (1996). Phosphorylation-dependent binding of BvgA to the upstream region of the cyaA gene of Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol 20, 489–496. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5231057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. R., Matthews R. C. (2000). Bordetella pertussis infection: pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and the role of protective immunity. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 19, 77–88. 10.1007/s100960050435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear S. M., Boucher P. E., Stibitz S., Carbonetti N. H. (1999). Analysis of BvgA activation of the pertactin gene promoter in Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 181, 5234–5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear S. M., Marques R. R., Carbonetti N. H. (2001). Differential regulation of Bvg-activated virulence factors plays a role in Bordetella pertussis pathogenicity. Infect Immun 69, 1983–1993. 10.1128/IAI.69.4.1983-1993.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontur W. S., Saecker R. M., Capp M. W., Record M. T., Jr (2008). Late steps in the formation of E. coli RNA polymerase-λPR promoter open complexes: characterization of conformational changes by rapid [perturbant] upshift experiments. J Mol Biol 376, 1034–1047. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey B. W. (1960). Antigenic modulation of Bordetella pertussis. J Hyg (Lond) 58, 57–93. 10.1017/S0022172400038134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert L. J., Wei Y., Schirf V., Demeler B., Werner M. H. (2004). T4 AsiA blocks DNA recognition by remodeling sigma70 region 4. EMBO J 23, 2952–2962. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson C. L., Swigon D., Murakami K. S., Darst S. A., Berman H. M., Ebright R. H. (2004). Catabolite activator protein: DNA binding and transcription activation. Curr Opin Struct Biol 14, 10–20. 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson G., Gutman G. A. (1987). Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Biol Evol 4, 203–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locht C., Antoine R., Jacob-Dubuisson F. (2001). Bordetella pertussis, molecular pathogenesis under multiple aspects. Curr Opin Microbiol 4, 82–89. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00169-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques R. R., Carbonetti N. H. (1997). Genetic analysis of pertussis toxin promoter activation in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol 24, 1215–1224. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4371792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteyn B., West N. P., Browning D. F., Cole J. A., Shaw J. G., Palm F., Mounier J., Prévost M. C., Sansonetti P., Tang C. M. (2010). Modulation of Shigella virulence in response to available oxygen in vivo. Nature 465, 355–358. 10.1038/nature08970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo S., Foreman-Wykert A. K., Cotter P. A., Miller J. F. (2001). Mechanisms of Bordetella pathogenesis. Front Biosci 6, e168–e186. 10.2741/Mattoo [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel T. J., Stibitz S., Keith J. M., Leef M., Shahin R. (1998). Contribution of regulation by the bvg locus to respiratory infection of mice by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 66, 4367–4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel T. J., Boucher P. E., Stibitz S., Grippe V. K. (2003). Analysis of bvgR expression in Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 185, 6902–6912. 10.1128/JB.185.23.6902-6912.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi F. R., van der Heide H. G. J., ter Avest A. R., Welinder K. G., Livey I., van der Zeijst B. A. M., Gaastra W. (1987). Characterization of fimbrial subunits from Bordetella species. Microb Pathog 2, 473–484. 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi F. R., Jansen W. H., Brunings H., Gielen H., van der Heide H. G. J., Walvoort H. C., Guinee P. A. M. (1992). Construction and analysis of Bordetella pertussis mutants defective in the production of fimbriae. Microb Pathog 12, 127–135. 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90115-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi F. R., van Loo I. H. M., van Gent M., He Q., Bart M. J., Heuvelman K. J., de Greeff S. C., Diavatopoulos D., Teunis P., et al. (2009). Bordetella pertussis strains with increased toxin production associated with pertussis resurgence. Emerg Infect Dis 15, 1206–1213. 10.3201/eid1508.081511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J., Sebaihia M., Preston A., Murphy L. D., Thomson N., Harris D. E., Holden M. T., Churcher C. M., Bentley S. D., et al. (2003). Comparative analysis of the genome sequences of Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Nat Genet 35, 32–40. 10.1038/ng1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx F., Toledano B., Phan V., Clermont M. J., Mariscalco M. M., Seidman E. G. (2002). Circulating granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, C-X-C, and C-C chemokines in children with Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Res 52, 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhen M., Dorman C. J. (2005). Hierarchical gene regulators adapt Salmonella enterica to its host milieus. Int J Med Microbiol 294, 487–502. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riboli B., Pedroni P., Cuzzoni A., Grandi G., de Ferra F. (1991). Expression of Bordetella pertussis fimbrial (fim) genes in Bordetella bronchiseptica: fimX is expressed at a low level and vir-regulated. Microb Pathog 10, 393–403. 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90084-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C. R., Falkow S. (1991). Identification of Bordetella pertussis regulatory sequences required for transcriptional activation of the fhaB gene and autoregulation of the bvgAS operon. J Bacteriol 173, 2385–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saecker R. M., Tsodikov O. V., McQuade K. L., Schlax P. E., Jr, Capp M. W., Record M. T., Jr (2002). Kinetic studies and structural models of the association of E. coli sigma(70) RNA polymerase with the lambdaP(R) promoter: large scale conformational changes in forming the kinetically significant intermediates. J Mol Biol 319, 649–671. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlato V., Aricò B., Prugnola A., Rappuoli R. (1991). Sequential activation and environmental regulation of virulence genes in Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J 10, 3971–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert H. S., So M. (1988). Genetic mechanisms of bacterial antigenic variation. Microbiol Rev 52, 327–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen P., Ullmann A. (1998). Hybrid Bordetella pertussis–Escherichia coli RNA polymerases: selectivity of promoter activation. J Bacteriol 180, 1567–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen P., Goyard S., Ullmann A. (1996). Phosphorylated BvgA is sufficient for transcriptional activation of virulence-regulated genes in Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J 15, 102–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stibitz S., Aaronson W., Monack D., Falkow S. (1989). Phase variation in Bordetella pertussis by frameshift mutation in a gene for a novel two-component system. Nature 338, 266–269. 10.1038/338266a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. (2000). Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 69, 183–215. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streisinger G., Owen J. (1985). Mechanisms of spontaneous and induced frameshift mutation in bacteriophage T4. Genetics 109, 633–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson M. S., Hammer B. K. (2000). Legionella pneumophila pathogesesis: a fateful journey from amoebae to macrophages. Annu Rev Microbiol 54, 567–613. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang R. S. W., Lau A. K. H., Sill M. L., Halperin S. A., Van Caeseele P., Jamieson F., Martin I. E. (2004). Polymorphisms of the fimbria fim3 gene of Bordetella pertussis strains isolated in Canada. J Clin Microbiol 42, 5364–5367. 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5364-5367.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl M. A., Miller J. F. (1996). Integration of multiple domains in a two-component sensor protein: the Bordetella pertussis BvgAS phosphorelay. EMBO J 15, 1028–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loo I. H. M., Heuvelman K. J., King A. J., Mooi F. R. (2002). Multilocus sequence typing of Bordetella pertussis based on surface protein genes. J Clin Microbiol 40, 1994–2001. 10.1128/JCM.40.6.1994-2001.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wintzingerode F., Schattke A., Siddiqui R. A., Rösick U., Göbel U. B., Gross R. (2001). Bordetella petrii sp. nov., isolated from an anaerobic bioreactor, and emended description of the genus Bordetella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51, 1257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Kita A., Kobayashi K., Miki K. (2008). Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 4121–4126. 10.1073/pnas.0709188105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems R., Paul A., van der Heide H. G., ter Avest A. R., Mooi F. R. (1990). Fimbrial phase variation in Bordetella pertussis: a novel mechanism for transcriptional regulation. EMBO J 9, 2803–2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. L., Boucher P. E., Stibitz S., Cotter P. A. (2005). BvgA functions as both an activator and a repressor to control Bvg phase expression of bipA in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol 56, 175–188. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. X., Zhou Y. N., Yang Y., Jin D. J. (2010). Polyphosphate binds to the principal sigma factor of RNA polymerase during starvation response in Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol 77, 618–627. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07233.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T., Manetti R., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (1996). Differential binding of BvgA to two classes of virulence genes of Bordetella pertussis directs promoter selectivity by RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol 21, 557–565. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]