Abstract

Opsismodysplasia is a rare, autosomal-recessive skeletal dysplasia characterized by short stature, characteristic facial features, and in some cases severe renal phosphate wasting. We used linkage analysis and whole-genome sequencing of a consanguineous trio to discover that mutations in inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 (INPPL1) cause opsismodysplasia with or without renal phosphate wasting. Evaluation of 12 families with opsismodysplasia revealed that INPPL1 mutations explain ∼60% of cases overall, including both of the families in our cohort with more than one affected child and 50% of the simplex cases.

Main Text

Opsismodysplasia (MIM 258480) is a rare skeletal dysplasia with delayed bone maturation (from “opsismos,” Greek for “late”).1–3 The clinical signs observed at birth include short limbs, small hands and feet, relative macrocephaly with a large anterior fontanel, and characteristic craniofacial abnormalities including a prominent brow, depressed nasal bridge, a small anteverted nose, and a relatively long philtrum. Death secondary to respiratory failure during the first few years of life was reported in the cases originally described but the outcome is now known to be highly variable with multiple long-term survivors.3 Typical radiographic findings include shortened long bones with very delayed epiphyseal ossification, severe platyspondyly, metaphyseal cupping, and characteristic abnormalities of the metacarpals and phalanges. Recurrence within sibships and incidence in consanguineous pedigrees suggest that the mode of inheritance of opsismodysplasia is autosomal recessive.1–6

To determine the genetic basis of opsismodysplasia, one of two siblings with opsismodysplasia and severe hypophosphatemia because of renal phosphate wasting (AII-1 in Table 1, Figures 1 and 2, and Figure S1 available online) and his consanguineous parents were genotyped with the HumanCytoSNP-12 DNA Analysis BeadChip, at nearly 300,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). All studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital and informed consent was obtained from participants or their parents. Self-reported Hispanic and Native American ancestry was first confirmed with EIGENSTRAT. Parametric linkage analysis by a fully penetrant rare recessive model (f2 = 1; q = 0.0001) and allele frequencies estimated from unrelated members of the HapMap CEPH, European, Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican American populations (Figure S2) was performed with ALLEGRO on an approximately 0.2 cM SNP map in an 11 person pedigree that included the consanguineous parents of the proband. Ten genomic regions reached a maximum LOD score of 1.5 (Figure S3). Homozygosity mapping via PLINK and default parameters (length = 1 Mb, # SNPs [n] = 100, density [kb/SNP] = 50, largest gap [kb] = 1 Mb) detected six of the regions also implicated via linkage analysis.

Table 1.

Mutations and Clinical Findings of Individuals with Opsismodysplasia

| Case identifier | AII-1 | AII-2 | BII-1 | CII-1 | DII-1 | EII-1 | FII-1 | FII-2 | GII-2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutations | |||||||||||||

| Exon (INNPL1) | 17 | 17 | 7 | 7 | intron 21 | 1 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 18 |

| Nucleotide | c.1976C>T | c.1976C>T | c.768_769del | c.768_769del | c.2415+1G>A | c.35dup | c.1687_1691del | c.545C>A | c.24_39del | c.753G>C | c.24_39del | c.753G>C | c.2071C>T |

| Peptide | p.Pro659Leu | p.Pro659Leu | p.Glu258Alafs∗45 | p.Glu258Alafs∗45 | NA | p.Ala13Argfs∗62 | p.Thr563Glyfs∗3 | p.Ser182∗ | p.Gly9Trpfs∗13 | p.Gln251His | p.Gly9Trpfs∗13 | p.Gln251His | p.Arg691Trp |

| GERP score | 5.43 | 5.43 | NA | NA | 5.52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.77 | NA | 4.77 | 3.7 |

| Predicted effect | missense | missense | frameshift | frameshift | splice site | frameshift | frameshift | nonsense | frameshift | missense | frameshift | missense | missense |

| Genotype | homozygous | homozygous | homozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | homozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | heterozygous | homozygous |

| Inheritance | maternal/ paternal | maternal/ paternal | maternal/ paternal DNA unavailable | maternal | paternal | NA | NA | NA | maternal | paternal | maternal | paternal | maternal/ paternal |

| Clinical Findings | |||||||||||||

| Ancestry | Hispanic/ Native American | Hispanic/ Native American | European American | European American | ND | Middle Eastern | African American/ European American | African American/ European American | Middle Eastern | ||||

| Consanguineous parents | 1st cousins once removed | 1st cousins once removed | no | no | no | 1st cousins | no | no | 1st cousins | ||||

| Prenatal findings | none | none | short limbs (3rd trimester) | short limbs at 26 weeks EGA, polyhydramnios | short limbs at 18–20 weeks EGA | oligohydram-nios | none | short limbs at 20 weeks | short limbs at 18.3 weeks, severe micromelia, and bell-shaped thorax at 22 weeks | ||||

| Birth length | ND | 46.5 cm | 43.8 cm | 45.7 cm | 43 cm | 49 cm | 43.1 cm | 47 cm | NA | ||||

| Birth weight | 3,380 g | 3,192 g | 3,120 g | 3,572 g | 2,745 g | 3,015 g | 3,100 g | 3,500 g | NA | ||||

| Birth OFC | ND | 35.6 cm | 38.5 cm (2 months) | ND | 35.5 cm | 35 cm | ND | 36.8 cm | NA | ||||

| Age at last evaluation | 8 years 8 months | 2 years 9 months | 19 months | 16 months | birth (34–35 weeks gestation) | 3 years | 24 years | 18 years | NA | ||||

| Macrocephaly | – | + (mild) | relative | relative | relative | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Large fontanel(s) | + | + | + | ND | ND | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Prominent forehead | + | + (mild) | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | ||||

| Tall forehead | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Hypertelorism | + | – | – | + | ND | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Long palpebral fissures | + | – | – | ND | ND | + | 90% | – | NA | ||||

| Proptosis/shallow orbits | + | – | + | + | ND | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Depressed nasal root | + | + | + | ND | + | + | + | + | + (absent nasal bone) | ||||

| Short nose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Abnormal ears | – | – | + | ND | + (low set) | + | posteriorly rotated, upturned lobules | – | – | ||||

| Respiratory insufficiency | + (ventilator dependent) | + (mild to moderate) | respiratory distress | recurrent pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension, restrictive lung disease | + (ventilated at birth) | + | restrictive lung disease, temporary tracheostomy, and ventilatory support for severe pneumonia at age 3 years | very mild intermittent reactive airway disease, obstructive sleep apnea requiring T & A, CPAP | NA | ||||

| Short hands/feet | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Soft and/or doughy skin | + | + | – | ND | ND | + | – | – | NA | ||||

| Psychomotor development | normal at 8.5 years | mild motor delay | mild motor delay, walked at 18 months | wheelchair dependent, normal intelligence | NA | + | motor delay | very mild motor delay | NA | ||||

| Hypophosphatemia | + | – | unknown | + | ND | + | + resolved age 9 years | + resolved age 14 years | NA | ||||

| Renal phosphate wasting | + | – | unknown | + | ND | + | + | + | NA | ||||

| DEXA scan results | prepamidronate whole body at 4 years 0.419, lastly at 8.5 years 0.58 | right distal femur at 6 months 0.289, at 3 years 0.672 (pamidronate × 2 years) | ND | osteopenia | ND | ND | age 17 yr. L2-L4 T score 0.852 g/cm2 | ND | NA | ||||

| Stature z scores | −9.5 | −4.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | −3.5 SD | ND | ND | ||||

| Other clinical features | dilated cardiomyop- athy, hypoplastic right kidney, left bronchial narrowing, history of oral aversion requiring GT feeds | ASD, asthma, left main stem bronchomala-cia, dysphagia/aspiration requiring GT feeds | inguinal hernia repair, facial asymmetry, high arched palate | ND | died of respiratory insufficiency at 1 week of age after being taken off ventilator | posterior cleft palate, micrognathia, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, difficulty swallowing requiring NG tube, partial renal tubular acidosis, tracheomalacia | small, narrow thorax, mild elbow and knee flexion contractures, hyperopia, mild systolic hypertension | mild elbow flexion contractures, mild bilateral low-frequency conductive hearing loss | ND | ||||

| Radiographic Findings | |||||||||||||

| Short long bones | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Metaphyseal irregularity and/or cupping | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Bony undermineralization | + | + | ND | ND | ND | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Fractures | + | – | – | – | – | + | + (ribs age 3 year, complication of hypophosphatemic rickets) | – | – | ||||

| Angulation of the long bones | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | ||||

| Delayed epiphyseal ossification | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | ||||

| Carpal ossification pattern/bone age | 3–6 months at 6 years 3 months | newborn at 12 months | newborn at 20 months | newborn at 24 months | ND | no ossification at 3 years | 15 years at 16 years 6 months | 5 years 6 months at 9 years 6 months | NA | ||||

| Short and square metacarpals and phalanges | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Other radiographic features | ND | calcaneal spurs | calcaneal spurs, odontoid hypoplasia | calcaneal spurs | ND | small, irregular middle phalanges with tapering and periosteal retraction | platyspondyly, small foramen magnum, cervical spinal canal stenosis from skull base to C4, hypoplastic square iliac wings and pubic bones, coxa vara, broad femoral heads, acetabular dysplasia (upsloping of lateral acetabuli) | platyspondyly, small foramen magnum, odontoid hypoplasia, cervical spinal canal stenosis from skull base to C3, hypoplastic square iliac wings, coxa vara | small and flat vertebral bodies, lumbar kyphosis, narrow chest, small and cupped pubic bones | ||||

Plus sign (+) indicates presence of a finding, minus sign (–) indicates absence of a finding. Abbreviations: ND, no data available; NA, not applicable, GERP, Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling; Birth OFC, birth occipital-frontal circumference; EGA, estimated gestational age; T & A, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; GT, gastrostomy tube; NG, nasogastric.

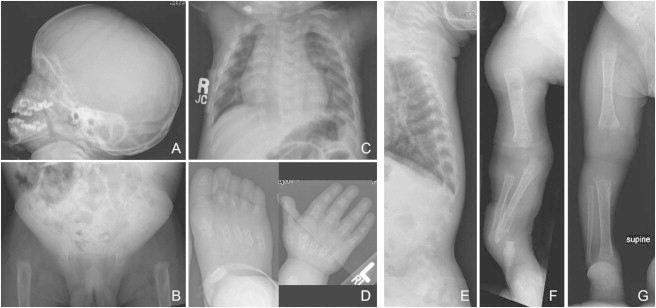

Figure 1.

Characteristic Physical Findings in Children and Adults with Opsismodysplasia

(A–D) Typical features of the face include relative macrocephaly, a prominent forehead, and a short nose with a depressed nasal bridge.

(E and F) Acquired abnormalities resulting from undermineralization of the long bones include bowing of the upper limb (E) and/or lower limb (F).

Case identifiers: AII-1 (A, E, F), AII-2 (B), FII-1 (C), and FII-2 (D), corresponding to those in Table 1, where a detailed description of each individual is provided.

Figure 2.

Radiographs of Individual AII-1 at 2 Years and 11 Months of Age

(A) Lateral image of skull showing midface hypoplasia and underdevelopment of the maxilla.

(B) Anterior-posterior (AP) image of the pelvis showing decreased mineralization, dislocated hips, poorly formed acetabula, and loss of normal architecture of the proximal femurs.

(C and E) AP image of the chest notable for under mineralization of the vertebrae and platyspondyly.

(D) The metacarus, metatarsus, and all of the phalanges are short and irregular with flared metaphyses.

(F and G) Delayed mineralization and absence of growth centers in the upper (F) and lower (G) limbs.

Next, whole-genome sequencing was performed on both parents and the same affected sibling used in the linkage studies. In brief, 1 μg of genomic DNA was subjected to a series of shotgun library construction steps, including fragmentation through acoustic sonication (Covaris), end-polishing (NEBNext End Repair kit), A-tailing (NEBNext dA Tailing kit), and ligation of 8 bp barcoded sequencing adaptors (Enzymatics Ultrapure T4 Ligase). Libraries were automatically size selected for fragments 350–550 bp in length with the automated PippinPrep cartridge system, which provides for fine control over the insert size and physically isolates each size fraction in separate chambers. Prior to sequencing, the library was amplified via PCR (Kapa HiFi Hotsart). To facilitate optimal flow-cell loading, the library concentration was determined by triplicate qPCR (Kapa Illumina Library Quantification kit) and molecular weight distributions verified on the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Massively parallel sequencing-by-synthesis via fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminating nucleotides was carried out on the HiSeq sequencer. Samples were sequenced to at least 30× average depth with paired-end 100 bp reads; a third read sequenced the 8 bp index to confirm sample assignments.

Demultiplexed BAM files were aligned to a human reference (hg19) with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.7 Read data from a flow-cell lane were treated independently for alignment and QC purposes in instances where the merging of data from multiple lanes was required. All aligned read data were subjected to (1) removal of duplicate reads, (2) indel realignment by the GATK IndelRealigner, and (3) base qualities recalibration via GATK TableRecalibration. Variant detection and genotyping were performed with the UnifiedGenotyper (UG) tool from GATK (refv1.529). Variant data for each sample were formatted (variant call format [VCF]) as “raw” calls that contained individual genotype data for one or multiple samples and flagged with the filtration walker (GATK) to mark sites that were of lower quality and potential false positives (e.g., quality scores [≤50], allelic imbalance [≥0.75], long homopolymer runs [>3], and/or low quality by depth [QD < 5]). Variant data were annotated with the SeattleSeq Annotation Server.

Regions under linkage peaks covering a total of ∼157 Mb were examined for rare and/or novel functional variation including missense, nonsense, splice site mutations, and indels. In the proband (AII-1), novel, homozygous missense mutations for which both parents were heterozygous were identified in five genes (INPPL1 [MIM 600829], VPS13A [MIM 605978], PRKDC [MIM 600899], NEU3 [MIM 604617], and CARNS1 [MIM 613368]; RefSeq NM_001567.3). Sanger sequencing of these variants in the affected sister of the proband (AII-2) revealed that she was homozygous only for variants in INPPL1, NEU3, and CARNS1, thus reducing the number of candidate genes to three. These candidates were further prioritized based on their putative biological function and screened via Sanger sequencing in an unrelated family with a single child with opsismodysplasia. In the first gene screened, INPPL1, the affected child (EII-1 in Table 1), who was the product of a consanguineous mating, was found to be homozygous for a nonsense mutation (c.545C>A [p.Ser182∗]).

To determine the extent to which INPPL1 mutations explain cases of opsismodysplasia, we used Sanger sequencing to screen ten additional unrelated families (total of ten affected individuals and the unaffected parents of a deceased child from whom a DNA sample was unavailable). These families consisted of nine trios in which an affected child was born to unaffected parents and one additional family with two affected siblings. Collectively, between the two families used for discovery and our validation studies, INPPL1 mutations were found in 7/12 (58%) kindreds tested (Table 1), including both families with more than one individual affected and 5/10 (50%) of the simplex cases. In each of the five families for which DNA was available from one or both parents, heterozygosity for the INPPL1 mutation was found. No other genes that cause phenotypes similar to opsismodysplasia were tested in the INPPL1 mutation-negative cases.

A total of nine unique mutations were identified including four frameshift, one nonsense, one splicing, and three missense mutations (Table 1; Figure 3). None of the INPPL1 missense, nonsense, or splice site mutations identified in the subjects were found in >13,000 chromosomes sequenced as part of the NHLBI-ESP. In three families, the affected individual(s) was a compound heterozygote. In four kindreds, including all three consanguineous families and one family that was not known to be consanguineous, the affected individuals were homozygous for an INPPL1 mutation. In the latter family (family B in Figure S1), inheritance of the mutation from the mother was confirmed, but the paternal sample was unavailable for testing. It is possible that the father is also a heterozygous carrier of this mutation, but a deletion encompassing the region could not be ruled out. However, this mutation (c.768_769del [p.Glu258Alafs∗45]) was also shared in a second unrelated family (family C in Figure S1) of European ancestry, indicating that there may be a carrier population with this variant.

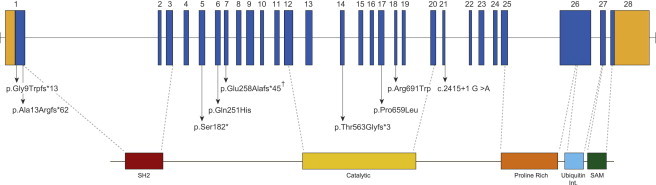

Figure 3.

Genomic Structure and Allelic Spectrum of INPPL1 Mutations that Cause Opsismodysplasia

INPPL1 is composed of 28 exons that encode untranslated regions (orange) and protein coding sequence (blue) domains including SH2 (red), catalytic (yellow), a proline-rich region (orange), ubiquitin-interacting region (light blue), and SAM (green). Arrows indicate the locations of nine different mutations found in seven families with opsismodysplasia. Inverted hatch mark indicates recurrent mutation.

Three of the frameshift mutations and the nonsense mutation are predicted to lead to premature termination codons at the 5′ end of the transcript, suggesting that they lead to loss of INPPL1 function. In particular, homozygosity for the Ser182∗ mutation found in the index case would eliminate most of the functional domains of the protein, including the catalytic domain (Figure 3). Thus, even if transcripts containing this mutation were stable to nonsense-mediated decay, the resulting truncated protein would be unlikely to retain significant function.

INPPL1 encodes inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 or SHIP2, a secondary messenger that has multiple roles in developmental processes including cellular proliferation, adhesion, and migration and metabolic functions such as glucose homeostasis and insulin signaling.8–10 Because of the role of SHIP2 in energy metabolism, it has been intensely studied both in vitro and in animal models. In mice, absence of SHIP2 protein or decreased expression of a catalytically inactive SHIP2 results in multiple developmental defects including a shortened facial profile and diminished growth.9,10 Specifically, the Inppl1−/− mice are about half the size of Inppl1+/+ mice, suggesting that the axial and appendicular skeleton must be affected.10 Inppl1 has been shown to be expressed at E14.5 in the developing axial and appendicular skeletal elements (Eurexpress), further supporting its role in skeletogenesis. The mechanism by which loss of SHIP2 affects skeletal development is unknown because, beyond its catalytic function, SHIP2 has been shown to act as a docking protein for many other cytoplasmic molecules.11

In summary, we used linkage analysis and whole-genome sequencing of a consanguineous trio to discover that mutations in INPPL1 cause opsismodysplasia and explain ∼60% of cases in our cohort. The clinical characteristics of individuals with opsismodysplasia caused by INPPL1 mutations were indistinguishable from those without INPPL1 mutations and included both individuals with severe renal phosphate wasting and those in whom no such abnormality had been reported. This observation suggests that opsismodysplasia is genetically heterogeneous. Our findings further support a role for SHIP2 in the development of the craniofacial, axial, and appendicular skeleton.10

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their participation and support. We thank Thomas Markello, Michael Bober, Arti Pandya, and J. Edward Spence for referral of subjects and Kathryn Millar, Ants Toi, and Sarah Keating for their assistance. Our work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute (1U54HG006493 and 1RC2HG005608 to M.J.B., D.A.N., and J.S.), the National Institute of Child Health and Development (HD22657 to D.H.C. and D.K., HHSN27500503415C to J.M.S., and HHSN267200700023C to E.M.F.), the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE019567 to D.H.C. and D.K.), the Life Sciences Discovery Fund (2065508 and 0905001), and the Washington Research Foundation.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Eurexpress, http://www.eurexpress.org/ee/

FASTX-Toolkit, http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/

HumanCytoSNP-12 DNA Analysis BeadChip, http://www.illumina.com/products/humancytosnp_12_dna_analysis_beadchip_kits.ilmn

Human Genome Variation Society, http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/

NHLBI Exome Variant Server/Sequencing Project (ESP), http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org/

Picard, http://picard.sourceforge.net/

SAMtools, http://samtools.sourceforge.net/

SeattleSeq Annotation 137, http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeqAnnotation137/

References

- 1.Zonana J., Rimoin D.L., Lachman R.S., Cohen A.H. A unique chondrodysplasia secondary to a defect in chondroosseous transformation. Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 1977;13(3D):155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maroteaux P., Stanescu V., Stanescu R., Le Marec B., Moraine C., Lejarraga H. Opsismodysplasia: a new type of chondrodysplasia with predominant involvement of the bones of the hand and the vertebrae. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1984;19:171–182. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320190117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cormier-Daire V., Delezoide A.L., Philip N., Marcorelles P., Casas K., Hillion Y., Faivre L., Rimoin D.L., Munnich A., Maroteaux P., Le Merrer M. Clinical, radiological, and chondro-osseous findings in opsismodysplasia: survey of a series of 12 unreported cases. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:195–200. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beemer F.A., Kozlowski K.S. Additional case of opsismodysplasia supporting autosomal recessive inheritance. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1994;49:344–347. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320490321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos H.G., Saraiva J.M. Opsismodysplasia: another case and literature review. Clin. Dysmorphol. 1995;4:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyler K., Sarioglu N., Kunze J. Five familial cases of opsismodysplasia substantiate the hypothesis of autosomal recessive inheritance. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;83:47–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990305)83:1<47::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clément S., Krause U., Desmedt F., Tanti J.F., Behrends J., Pesesse X., Sasaki T., Penninger J., Doherty M., Malaisse W. The lipid phosphatase SHIP2 controls insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2001;409:92–97. doi: 10.1038/35051094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois E., Jacoby M., Blockmans M., Pernot E., Schiffmann S.N., Foukas L.C., Henquin J.C., Vanhaesebroeck B., Erneux C., Schurmans S. Developmental defects and rescue from glucose intolerance of a catalytically-inactive novel Ship2 mutant mouse. Cell. Signal. 2012;24:1971–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleeman M.W., Wortley K.E., Lai K.M., Gowen L.C., Kintner J., Kline W.O., Garcia K., Stitt T.N., Yancopoulos G.D., Wiegand S.J., Glass D.J. Absence of the lipid phosphatase SHIP2 confers resistance to dietary obesity. Nat. Med. 2005;11:199–205. doi: 10.1038/nm1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erneux C., Edimo W.E., Deneubourg L., Pirson I. SHIP2 multiple functions: a balance between a negative control of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 level, a positive control of PtdIns(3,4)P2 production, and intrinsic docking properties. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:2203–2209. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.