Abstract

Sun exposure has been clearly implicated in premature skin aging and neoplastic development. These features are exacerbated in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), a hereditary disease, the biochemical hallmark of which is a severe deficiency in the nucleotide excision repair of UV-induced DNA lesions. To develop an organotypic model of DNA repair deficiency, we have cultured several strains of primary XP keratinocytes and XP fibroblasts from skin biopsies of XP patients. XP skin comprising both a full-thickness epidermis and a dermal equivalent was succesfully reconstructed in vitro. Satisfactory features of stratification were obtained, but the expression of epidermal differentiation products, such as keratin K10 and loricrin, was delayed and reduced. In addition, the proliferation of XP keratinocytes was more rapid than that of normal keratinocytes. Moreover, increased deposition of cell attachment proteins, α-6 and β-1 integrins, was observed in the basement membrane zone, and β-1 integrin subunit, the expression of which is normally confined to basal keratinocytes, extended into several suprabasal cell layers. Most strikingly, the in vitro reconstructed XP skin displayed numerous proliferative epidermal invasions within dermal equivalents. Epidermal invasion and higher proliferation rate are reminiscent of early steps of neoplasia. Compared with normal skin, the DNA repair deficiency of in vitro reconstructed XP skin was documented by long-lasting persistence of UVB-induced DNA damage in all epidermal layers, including the basal layer from which carcinoma develops. The availability of in vitro reconstructed XP skin provides opportunities for research in the fields of photoaging, photocarcinogenesis, and tissue therapy.

Keywords: three-dimensional skin model, xeroderma pigmentosum, UVB radiation, DNA damage, keratinocyte differentiation

The major consequences of UV (ultraviolet) radiation from sunlight are skin photoaging and cancer development (1, 2). The dramatic effects of UV radiation are demonstrated in patients affected with the genetic disease xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) (3), the cellular biochemical hallmark of which is a defect in nucleotide excision repair (NER) for UV-induced mutagenic DNA lesions (4). NER is the most versatile repair process of UVB-induced DNA lesions, such as 6–4 pyrimidine pyrimidone photoproducts and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs). It involves five enzymatic steps: (i) recognition of the DNA lesion; (ii) DNA unwinding to form a “bubble;” (iii) 5′ and 3′ single-strand DNA incision in the DNA strand bearing the UV lesion; (iv) DNA gap filling by repair replication, with the intact strand as template; and, ultimately, (v) ligation of the newly synthesized DNA patch. Alteration of some of the early steps of the NER process results in one of the seven XP complementation groups (XP-A to XP-G), defined biochemically by somatic cell fusion (5). The persistence of UV-induced DNA lesions is mutagenic during DNA replication and may result in tumor development (6). Indeed, the NER deficiency in XP patients results in a high predisposition (×2,000, compared with the general population) to developing epidermal skin tumors in sun-exposed body areas (3). The study of the responses of XP skin cells in their natural three-dimensional environment is precluded by ethical considerations, ruling out experimental trials that include UV irradiation of XP volunteers. In addition, because of their limited thickness and consequent poor differentiation capacity, classical keratinocyte cultures (i.e., on plastic) do not take into account the three-dimensional tissue architecture in epithelial–mesenchymal interaction-mediated effects on UV-induced skin aging and cancer development. Finally, introducing DNA repair defects by genetic recombination in laboratory mice may result in phenotypic traits that sometimes are at variance with those of the corresponding human syndromes (7).

Alternative attempts to analyze tissue and cell damage induced by UV radiation in normal individuals (8–10) and photoprevention (11) have ensued from engineering fully differentiated normal human skin in vitro. Actually, skin reconstructed in vitro was shown to reproduce most stages of the stepwise epidermal differentiation program, starting with basal, undifferentiated keratinocytes, up to the ultimate steps of maturation, illustrated by the formation of cornified layers as in normal epidermis in vivo (12, 13). Nevertheless, in vitro organotypic human systems able to reliably mimic photosensitive skin have never been developed, despite their numerous potential fundamental applications.

In this report, we present the development of an in vitro photosensitive human skin model developed from cells from several independent primary (i.e., not transformed) strains of epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts obtained from skin biopsies of unexposed body areas of XP patients (14). All of these belong to the XP-C complementation group, the clinical hallmarks of which are photosensitivity, skin aging, and proneness to cancer, but which are not associated with the neurodegenerative symptoms sometimes found in XP-D and -A patients (15).

We show that XP skin can be reliably reconstructed in vitro from XP keratinocytes and XP fibroblasts and, most importantly, that it retains the DNA repair deficiency of XP skin in vivo (3). Although it exhibits mostly normal morphological features, the in vitro reconstructed XP skin exhibited alterations in the keratinocyte differentiation program, accompanied by an increased rate of proliferation. Still more significantly, the in vitro reconstructed XP skin displayed striking epidermal invasions within the dermis, a characteristic of early steps of epidermal neoplastic development. The XP skin model reported in this paper thus opens prospects for the study of tissue factors that contribute to UV-induced skin carcinogenesis and aging. It may also provide clues to the development of tissue gene therapy of XP.

Materials and Methods

Patients.

All patients presented a marked photosensitivity. Unless otherwise indicated, all patients were independent. Patient XP148VI had developed multiple skin tumors from the age of 9 years, as described (14). Patients XP374VI (4 years old), XP373VI (3 years old) (XP 374VI's brother), and XP399VI (5 years old) had developed several cutaneous tumors from the age of 2. Patient XP424VI (18 years old) had developed three basal cell carcinomas from the age of 15 and presented numerous freckles and nevi on sun-exposed skin.

Skin Biopsies and Cell Culture.

Normal human skin was obtained from mammary plastic surgery.

XP skin biopsies from nonexposed (to sunlight) and normally pigmented sites (buttock) were obtained with the patient's or parents' informed consent. Human normal and XP keratinocytes and fibroblasts were obtained and cultured as described (14, 16).

Determination of XP Complementation Group.

XP keratinocytes were infected by retroviral particles expressing wild-type XP cDNAs, and the complementation groups were determined by described procedures (17, 18).

Reconstructed Skin in Vitro.

In all experiments, fibroblasts and keratinocytes were used at the same passages, P4 and P2, respectively. Reconstructed skin was prepared essentially as described in detail (12), except for minor modifications according to related XP strain (see below). The principle of skin reconstruction relied on the production of lattice in which fibroblasts were embedded in a type I collagen gel. After contraction of the lattice, 5 × 104 normal, to up to 3 × 105 XP keratinocytes (AS148, 3 × 105; AS374, 1 × 105; AS399, AS424, 2 × 105) were seeded onto a 1.5-cm2 lattice. Keratinocytes overlying the dermal equivalent (lattice) were then incubated for 7 (normal) to 8 days (XP) immersed in culture medium before being raised at the air–liquid interface (emersion period) for a time ranging from 7 days for normal and XP AS374A cells to 8 (AS148) or 9 days for AS399 and AS424.

Irradiation Sources and Procedures.

UVB irradiation was performed with Philips TL20W/12 fluorescent tubes (Lumiéres Service, Paris) equipped with a Kodacel filter. UV spectra and procedures were as described (10).

Classical Histology.

Samples were fixed in neutral formalin. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin, eosin, and saffron (8).

Immunostaining.

Immunolabeling was performed on air-dried vertical 5-μm cryosections as described (8).

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against various proteins were obtained from the following sources: keratin 10/RKSE 60 (1:5), Sanbio, Uden, The Netherlands; human filaggrin (1:100) and keratinocyte transglutaminase (1:20), Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA; thymine dimers (H3) (1:50): L. Roza, Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research, Zeist, The Netherlands (19); human vimentin (1:10), Monosan, Unden, The Netherlands; Ki-67 (1:20), NovoCastra, Newcastle, U.K.; integrin α-6 (1:10): GoH3, Immunotech, Luminy, France; integrin β-1 (1:50): K20, Immunotech.

Rabbit polyclonal antiserum was against human loricrin (1:40) (T. Magnaldo et al., ref. 20).

FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse or swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako) were used as secondary antibodies (1:100). (1:X) indicates the appropriate dilution of antibodies in PBS.

Detection of thymine dimers was carried out (19) on methanol/acetic acid (3:1) fixed sections, followed by denaturation with NaOH (0.07 M in 70% ethanol) and partial digestion with proteinase K (1 μg/ml).

Results and Discussion

Reconstruction of XP Epidermis on a DNA Repair-Proficient Dermal Equivalent Reveals Altered Keratinocyte Differentiation and Proliferation.

XP epidermis displaying apparent satisfactory features of stratification and differentiation (21) could be reconstructed on a DNA repair-proficient dermis. An increased (×2–×6) number of cells was seeded onto the dermal equivalent, compared with the normal skin model. The capacity of the epidermal cells to divide and their life span could be realized quite faithfully in vitro by their ability to form colonies (16, 22). Despite the higher amounts of XP-C keratinocytes required to fully reconstruct epidermis in vitro, their colony-forming efficiency (CFE) values were in a range similar to that of normal cells [e.g., CFE values from NHK9 (normal) and AS374 A (XP-C) keratinocyte strains were both 10%]. This apparent discrepancy suggested that three-dimensional culture conditions might reveal intrinsic alterations in the control of XP keratinocyte proliferation that are not detectable under standard culture conditions.

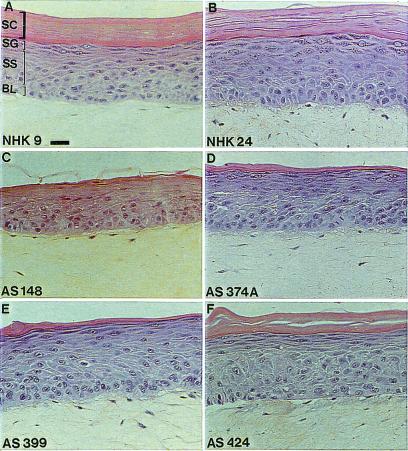

Histology of reconstructed XP epidermis made from epidermal XP keratinocytes revealed a stratum corneum (outermost terminally differentiated layers) with a significantly reduced thickness, suggesting an impaired capacity of XP-C keratinocytes to terminally differentiate, compared with normal controls (12, 21) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the stratum corneum of in vitro reconstructed XP epidermis did not contain persisting nuclei, an abnormality called parakeratosis, which accompanies some cutaneous hyperproliferative syndromes (23).

Figure 1.

Histology of skin reconstructed in vitro from normal and XP-C keratinocytes on normal dermal equivalent. (A and B) Normal keratinocytes. (C–F) XP-C keratinocytes from four different, independent XP patients. BL, basal layer; SS, stratum spinosum; SG, stratum granulosum; SC, stratum corneum. Cultures were obtained according to optimized conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Note that the histologies of normal and XP-C epidermis look closely similar, except for a thinner stratum corneum in all XP-C epidermis. (Bar = 50 μm.)

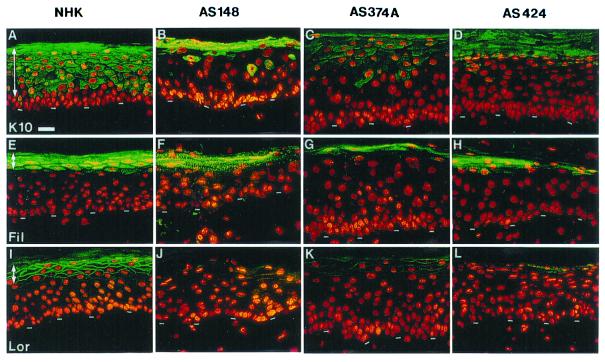

The expression of major biochemical markers of epidermal differentiation (13) was monitored by immunocytochemistry with specific antibodies (see Materials and Methods). Keratin K10, a typical early differentiation marker normally expressed from the first suprabasal epidermal layer up to the granular layer (21), was expressed later on in the differentiation process (i.e., in upper layers), and its amount was markedly reduced in all four XP-C strains examined (Fig. 2). However, it was an unexpected finding that reduced K10 protein expression did not result from reduced transcriptional activity of the K10 gene in XP-C keratinocytes, as evidenced by transient transfection experiments with K10 gene keratin promoter upstream of a reporter gene (24) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Altered expression of keratinocyte differentiation markers in the in vitro reconstructed XP-C epidermis on a normal dermal equivalent. (A, E, and I) Normal epidermis reconstructed from normal human keratinocytes (NHK). (B–D, F–H, J–L) XP-C epidermis reconstructed from XP-C keratinocytes strains AS148, AS 374A, and AS424, as indicated. Immunolabeling: A–D, K10 keratin (K10); E–H, filaggrin (Fil); I–L, loricrin (Lor). In the left column, arrows indicate the normal area of expression of markers studied. Note the alterations, delayed and decreased expression of K10, filaggrin, and loricrin, in all three XP-C strains compared with normal keratinocytes. The dashed line indicates the dermal–epidermal junction. (Bar = 50 μm.)

Immunocytochemistry of differentiation markers such as loricrin and filaggrin, which are involved in the ultimate steps of keratinocyte differentiation leading to cornified envelope formation (21), also revealed markedly decreased expression in all four keratinocyte XP-C strains analyzed and compared with normal controls (Fig. 2). In contrast, the distribution of epidermal transglutaminase, another terminal keratinocyte differentiation marker involved in cornified envelope assembly (21), was not evidently altered in the in vitro reconstructed XP epidermis (data not shown). Thus, only some differentiation proteins (i.e., K10, loricrin, filaggrin) were found to be altered in in vitro reconstructed XP epidermis. Although there are major clinical and histogical differences between XP and the human hyperproliferative syndrome psoriasis, the delayed and reduced expression of K10 (25), loricrin (26), and filaggrin and slightly affected transglutaminase (27, 28) have also been found in skin biopsies taken from patients with psoriasis.

We then compared the rate of keratinocyte proliferation in normal versus reconstructed XP epidermis with the use of a proliferation-associated antigen, Ki-67. Whereas cell multiplication was confined to a minority of basal cells (about 10%) in normal reconstructed epidermis, it extended to virtually all basal keratinocytes and to few suprabasal cells in the reconstructed XP epidermis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Increased proliferation in XP-C epidermis reconstructed in vitro on a normal dermal equivalent. (A, E, and I) Normal epidermis reconstructed from normal human keratinocytes (NHK). (B–D, F–H, J–L) XP-C epidermis reconstructed from XP-C keratinocyte strains AS148, AS374A, and AS424, as indicated. Immunolabeling: A–D, proliferation-associated Ki-67 antigen (Ki 67); E–H, α-6 integrin; I–L, β-1 integrin (beta 1). Note that virtually all nuclei are labeled with anti-Ki-67 antibody in all XP-C epidermis, whereas about 10% only are found in normal epidermis (NHK). Also note the increased deposition of α-6 and β-1 integrins at the basement membrane zone of XP-C compared with normal epidermis. In XP-C epidermis also, β-1 integrin is abnormally expressed in several suprabasal layers above the basal layer, whereas it is restricted in normal epidermis. Arrows point to the nascent epidermal invasions within the dermal equivalent, as indicated by β-1 integrin staining. The dashed line indicates the dermal–epidermal junction. (Bar = 50 μm.)

Because attachment of basal keratinocytes to the basement membrane via integrins plays an active role in the control of cell proliferation (29), we assessed the expression of integrin subunits β-1 and α-6 specific to basal keratinocytes. Immunolabeling revealed that deposition of these proteins at the basement membrane zone was increased in XP epidermis compared with normal epidermis reconstructed in vitro (Fig. 3). In addition to a much brighter signal at the basement membrane zone than in normal epidermis, β-1 integrin was also not restricted to basal keratinocytes but extended to several suprabasal cell layers in reconstructed XP epidermis (Fig. 3). Furthermore, staining of both α-6 and β-1 integrins underscored slight nascent epidermal invaginations within the dermal equivalent, the importance of which was amplified in the presence of a dermal equivalent containing XP fibroblasts (see below).

Higher levels of β-1 integrin have been ascribed to keratinocytes with characteristics of stem cells (30–33). Conversely, ectopic expression of β-1 integrin in the suprabasal keratinocytes of transgenic mice and in the in vitro reconstructed epidermis has resulted in epidermal alterations resembling psoriatic epidermis, such as keratinocyte hyperproliferation and delayed onset of differentiation (34, 35). Although transient keratinocyte hyperproliferation has been correlated with suprabasal expression of integrins (α-3 and β-1) in normal in vitro reconstructed human epidermis (36), it remains to be determined whether suprabasal integrin expression may result in, or is only secondary to, keratinocyte hyperproliferation in in vitro reconstructed XP epidermis.

To establish that the observed alteration of epidermal differentiation and proliferation was not because of culture conditions, a small number of biopsies from normal and XP skins were analyzed. Histological stainings did not reveal major differences (or alteration) of epidermal structures in normal versus XP skin biopsies. In contrast, labeling of differentiation markers revealed slight alterations (delayed and reduced expression) of K10 keratin and a slight decrease in loricrin in XP skin as compared with normal skin maintained in the same conditions before analysis (i.e., up to 4 days in serum containing medium, as sometimes happens with shipment of biopsies to the laboratory). Furthermore, the expression of β-1 integrin was increased and detected in several suprabasal keratinocyte layers in XP but not in normal epidermis (data not shown). We conclude that in vitro reconstructed XP epidermis closely resembles XP epidermis ex vivo. Our model of reconstructed XP skin thus appears as a faithful physiological system, able to reproduce subtle and as-yet-unreported traits of the XP skin phenotype in the absence of UV irradiation.

XP Fibroblasts Provoke Epidermal Invasions of Normal and XP Keratinocytes Within the Dermal Equivalent.

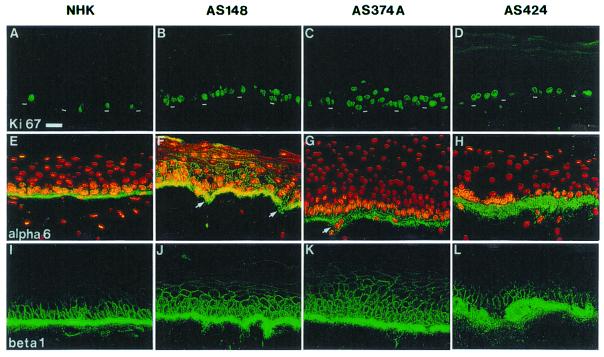

According to their tissue origin or their association with cutaneous abnormalities, dermal fibroblasts have been shown to influence the behavior (differentiation and proliferation) of epidermal keratinocytes in organotypic cultures (37–40). To assess their influence on keratinocyte growth and epidermal morphogenesis, XP fibroblasts from three independent strains (AS148, AS374, AS424) were introduced into a dermal equivalent overlaid with either normal or XP keratinocytes.

Normal keratinocytes seeded onto XP dermal equivalents formed a fully differentiated epidermis and displayed a normal histological appearance (i.e., presence of spinous, granular, and horny layers), as well as a pattern of expression of differentiation markers similar to that of controls. However, frequent invaginations of normal keratinocytes within the XP dermal equivalent were observed by histology and immunolabeling of α-6 and β-1 integrins (Fig. 4). When XP keratinocytes were seeded onto a XP dermal equivalent to reconstruct a complete XP skin, epidermal invaginations were larger and more frequent than in heterologous skins comprising solely a XP dermal equivalent.

Figure 4.

Invasions of normal or XP-C epidermis in dermal equivalent containing XP-C fibroblasts. (A and B) Histology. (C and D) α-6 integrin labeling. (E and F) β1 integrin labeling. (F) Higher magnification of β1 integrin staining showing a continuity of its expression between epidermis and epidermal invasions. (G and H) Ki-67 immunostaining of in vitro reconstructed skin from XP-C fibroblasts and keratinocytes. In G, nuclei have been stained with propidium iodide (red). Note that the presence of XP-C fibroblasts results in epidermal invasions. Ki-67 immunostaining reveals proliferation in epidermal invasions. KXP indicates in vitro reconstructed epidermis from the AS374A strain; XPF indicates that XP-C fibroblasts from the AS373 strain were used to reconstruct the dermal equivalent. KHN indicates in vitro reconstructed epidermis from normal human keratinocytes. The dashed line indicates the dermal–epidermal junction. (Bar = 25 μm.)

Labeling of Ki-67 antigen revealed an increased rate of keratinocyte proliferation in epidermal invasions formed by both normal and XP keratinocytes on the XP dermal equivalent (Fig. 4).

Together, these observations indicated that the presence of XP fibroblasts in the dermal equivalent leads to the formation of large and frequent epidermal invasions in heterologous (normal keratinocytes) or complete XP skins (XP keratinocytes), respectively (Fig. 4). Enhancement of epidermal invasions in complete XP skins suggested the additive or synergistic contribution of both keratinocytes and fibroblasts in this phenomenon.

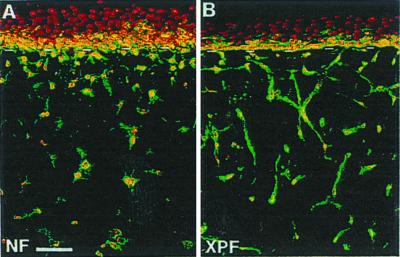

XP Fibroblasts Spontaneously Orient Abnormally in the Dermal Equivalent and Lead to Retraction of Dermal Equivalents.

The possible role of XP fibroblasts in the formation of epidermal invasions was assessed by studying their behavior at the macro- and microscopic levels in the three-dimensional dermal equivalent. Strikingly, the presence of XP fibroblasts resulted in significantly smaller diameters of the lattices (23.3 ± 3.3% at 24 h; 24.7 ± 3.3% at 96 h) than with control cells. Histology and staining of vimentin, a marker of mesenchymal cells, revealed that XP fibroblasts tend to massively orient perpendicular to the plane of the dermal–epidermal junction. In comparison, normal fibroblasts appeared mostly in random orientations (Fig. 5). These differences in the XP compared with a normal dermal equivalent strongly suggested that XP fibroblasts provoke profound modifications of the content and/or the organization of extracellular matrix components. In this respect, Scott et al. (41) have shown that a potent inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases, Marimastat, inhibited fibroblast-mediated contraction of a dermal equivalent populated by normal dermal fibroblasts, hence suggesting by analogy that in an XP dermal equivalent, increased matrix metalloproteases (42) may be produced.

Figure 5.

Abnormal cell orientation and increased contraction in XP-C dermal equivalent. (A and B) Vimentin labeling in normal (NF) or XP-C (XPF, AS-148) fibroblast-containing dermal equivalent. Note that normal fibroblast orientation is mostly random, whereas XP-C fibroblast tend to orient perpendicular to the dermal-epidermal junction. Three independent XP-C fibroblast strains were tested. (Bar = 25 μm.)

This hypothesis is currently being tested. Its confirmation at the molecular level should provide additional clues to the basis for the epidermal cancer proneness of XP patients (43) and premature features of skin aging (44, 45).

In Vitro Reconstructed XP Epidermis as a Unique Three-Dimensional Model of DNA Repair Deficiency.

As an attempt to evaluate the capacity of XP keratinocytes to repair UVB-induced DNA lesions within in vitro reconstructed epidermis, biologically efficient UVB doses (BEDs) were determined as described (8). BED was defined as the minimal UVB dose able to induce the formation of sunburn cells in suprabasal cell layers of in vitro reconstructed normal epidermis 24 h after exposure to a single UVB irradiation. There is a narrow correspondence between BED or sunburn cell formation in vitro and mean minimal erythemal dose as measured after UVB irradiation of normal volunteers (8, 46).

BEDs of in vitro reconstructed XP-C epidermis were found in the range of BEDs of reconstructed normal epidermis (i.e., 500–800 J/m2) (BEDs of XP-C epidermis: AS148, 300 J/m2; AS374A, 800 J/m2; AS399, 600 J/m2; AS424, 600 J/m2), which is in agreement with results obtained from laboratory mice with disrupted XPC alleles (XPC−/−), which exhibit minimal erythemal dose values similar to those of normal or heterozygous animals (XPC+/−) (47, 48). In contrast, XPA−/− or CSB−/− mice exhibit minimal erythemal dose values three to four times lower than those of wild-type or XPC−/− mice. These differences presumably result from the persistence of UVB lesions on the transcribed strand of active genes in XP-A−/− and CSB−/− (47, 48) but not in XPC−/− mice, whose DNA repair defect only concerns the global repair pathway (49).

The lowest BED value was found in the XP-C keratinocyte strain with the poorest capacity to develop thick horny layers (AS148, Fig. 1), suggesting a protective role of stratum corneum. UVB penetration and absorption throughout the stratum corneum and normal epidermis, however, seem to be far less significant (50) than assumed (51). Nevertheless, our previous investigations in classical cultures (i.e., on plastic) had shown that a particular UVB irradiation induced twice as many DNA lesions (6–4 pyrimidine pyrimidone photoproducts and CPDs) in normal fibroblasts as in keratinocytes (14). In skin epidermal keratinocytes in vivo, at least 70% of protein synthesis is devoted to keratins. We had suggested that normal expression of these proteins might help to shield against UVB and perhaps lead to epidermal cancer protection (14). Impaired K10 expression observed in all XP-C epidermal cultures in our study might alter this natural protection.

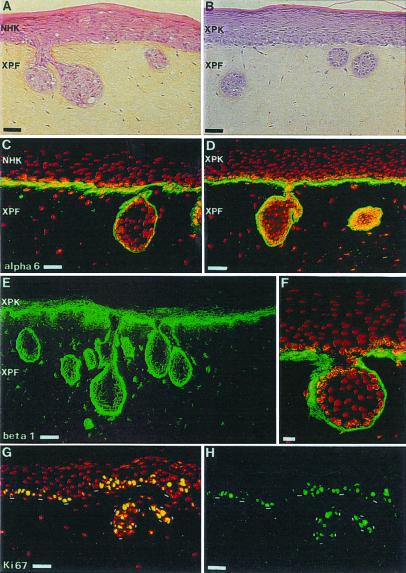

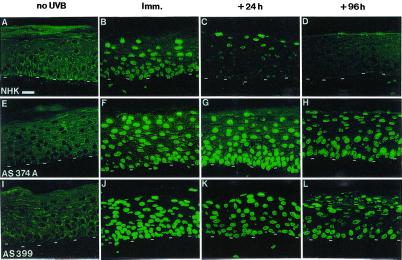

XP and normal epidermis reconstructed in vitro on a normal dermal equivalent were then exposed to appropriate UVB BEDs and harvested at various times after irradiation. CPD DNA lesions were detected with the use of the H3 monoclonal antibody (8, 19). Immediately after irradiation, CPD lesions were detected similarly in all nuclei throughout both normal and XP epidermis, regardless of the depth (Fig. 6). Twenty-four hours after UVB irradiation, CPD lesions were no longer detected in the basal layer of normal reconstructed epidermis, whereas in suprabasal layers most nuclei remained clearly positive. In contrast, 24 h after UVB irradiation of XP epidermis, CPD lesions in the basal layer remained at a level similar to that observed initially. Ninety-six hours after irradiation, DNA lesions were no longer detectable in any viable layers of normal epidermis (i.e., basal and suprabasal layers), whereas they persisted in an amount virtually identical in all layers of XP epidermis. In comparison with other XP-C epidermis, epidermis reconstructed from AS424 keratinocytes showed a slight attenuation of DNA lesions 96 h after irradiation. This finding could be correlated with the relatively moderate photosensitivity and cancer proneness of this XP-C patient (only three basal cell carcinomas at the age of 18). Likewise, residual NER DNA repair of AS424 fibroblasts was relatively high (about 20%) compared with other XP-C fibroblasts (AS148, AS399, and AS374A) that exhibited about 10% residual repair) (not shown). In addition, in the four XP-C keratinocyte strains tested, exposure to UVB led to parakeratosis that was more pronounced than in normal epidermis (8) 96 h after irradiation. In one of the four XP-C strains (AS374A), suprabasal sunburn cells remained visible 96 h after irradiation, whereas they had disappeared in other cultures.

Figure 6.

DNA repair deficiency in in vitro reconstructed XP-C epidermis, revealed by immunostaining of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers after UVB exposure. CPD labeling: A, E, I, in the absence of UVB irradiation (no UVB); B, F, J, immediately after one BED irradiation (Imm., t = 0) (NHK: 800 J/m2; AS374A: 800 J/m2; AS399: 600 J/m2); C, G, K, 24 h after irradiation (+24 h); D, H, L, 96 h after irradiation (+96 h). Note the complete disappearance of CPD lesions from the basal and suprabasal layers of normal epidermis and the persistence of these DNA damages in all epidermal cell layers of XP-C epidermis. This persistence of damage illustrates in situ DNA repair deficiency of XP-C keratinocytes in in vitro reconstructed skin. The dashed line indicates the dermal–epidermal junction. (Bar = 50 μm.)

These data demonstrated, with the use of a three-dimensional culture system, the persistence of UVB-induced DNA damage in all layers of XP epidermis up to 96 h after irradiation. In particular, the persistence of lesion-bearing nuclei in basal keratinocytes in reconstructed XP epidermis, but not in normal epidermis, anticipated mutagenic events in the proliferative equivalent of tissue containing stem keratinocytes (33, 52). In vitro reconstructed XP epidermis is thus a unique human system allowing the study of epidermal cell fate in the absence of efficient DNA repair, i.e., with high mutagenesis potential (49). In this respect, crucial issues will rely on the study of genes such as p53, the structural integrity of which warrants the control of cell proliferation, and the function of which is frequently lost or impaired after the introduction of UV-induced mutations in basal and squamous cell carcinoma in both normal (1) and XP individuals (53).

Together with the high proneness of XP keratinocytes to invade XP dermal equivalent (Fig. 5), potential UVB-induced mutagenesis in those basal cells endowed with high growth potential (stem or transit amplifying keratinocytes) (52) in XP epidermis may then offer an interesting alternative system for studying epidermal cancer development in vitro.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that XP skin could now reliably be reconstructed in vitro and thus defines a human model suitable for the study of a genetic DNA repair defect (photosensitivity) with accurate three-dimensional tissue architecture in vivo. The high UV sensitivity of the reconstructed XP skin model allows us to analyze the effects of UVs, including low doses, with special attention to early molecular events involved in skin photoaging and cancer. In this respect, this model should contribute to the enhancement of the efficiency of sun protection (11) against broad UV ranges. In vitro reconstruction of complex XP skin, including melanocytes and immune skin cells (Langerhans cells), should further improve the biological relevance of our model. Finally, the possibility of reverting to the DNA repair deficiency of XP epidermal keratinocytes as well as of XP fibroblasts (54, 55) allows the reconstruction of DNA repair proficient XP skins and provides perspectives on tissue therapy.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. J. Leclaire for his continuous support and encouragement. T.M. is supported by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC 1711; ARC 9500) and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Abbreviations

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- CPDs

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers

- BED

biologically efficient UVB dose

References

- 1.Brash D E. Trends Genet. 1997;13:410–414. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraemer K H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraemer K, Lee M, Scotto J. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:241–250. doi: 10.1001/archderm.123.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford J M, Hanawalt P C. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;221:47–70. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60505-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Boer J, Hoeijmakers J H. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:453–460. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraemer K H, Lee M M, Scotto J. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:511–514. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg E C. Cancer J Sci Am. 1999;5:257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernerd F, Asselineau D. Dev Biol. 1997;183:123–138. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haake A, Polakowska R. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:183–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernerd F, Sarasin A, Magnaldo T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11329–11334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernerd F, Vioux C, Asselineau D. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;71:314–320. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0314:EOTPEO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asselineau D, Bernard B, Bailly C, Darmon M. Exp Cell Res. 1985;159:536–539. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(85)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs E, Byrne C. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:725–736. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto A, Riou L, Marionnet C, Mori T, Sarasin A, Magnaldo T. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1212–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bootsma D, Kraemer K, Cleaver J, Hoeijmaker J. In: The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer. Vogelstein B, Kinzler K, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1998. pp. 245–274. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rheinwald J G, Green H. Cell. 1975;6:331–344. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(75)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carreau M, Quilliet X, Eveno E, Salvetti A, Danos O, Heard J M, Mezzina M, Sarasin A. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1307–1315. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.10-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng L, Sarasin A, Mezzina M. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;113:87–100. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-675-4:87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roza L, De Gruijl F R, Bergen Henegouwen J B, Guikers K, Van Weelden H, Van Der Schans G P, Baan R A. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:903–907. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12475429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnaldo T, Bernerd F, Asselineau D, Darmon M. Differentiation (Berlin) 1992;49:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1992.tb00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs E. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2807–2814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrandon Y, Green H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grosshans E, Caussade P. In: Dermatologie et Vénéréologie. Saurat J, Grosshans E, Laugier P, Lachapelle J, editors. Paris: Masson; 1991. pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang C K, Epstein H S, Tomic M, Freedberg I M, Blumenberg M. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:162–167. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12460939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernerd F, Magnaldo T, Darmon M. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:902–910. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12460344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juhlin L, Magnaldo T, Darmon M. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1992;72:407–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder W T, Thacher S M, Stewart-Galetka S, Annarella M, Chema D, Siciliano M J, Davies P J, Tang H Y, Sowa B A, Duvic M. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:27–34. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12611394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernard B A, Reano A, Darmon Y M, Thivolet J. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giancotti F, Ruoslaahti E. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones P H, Watt F M. Cell. 1993;73:713–724. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90251-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones P H, Harper S, Watt F. Cell. 1995;80:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen U B, Lowell S, Watt F M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:2409–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones P H. BioEssays. 1997;19:683–690. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll J M, Romero M R, Watt F M. Cell. 1995;83:957–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero M R, Carroll J M, Watt F M. Exp Dermatol. 1999;8:53–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rikimaru K, Moles J P, Watt F M. Exp Dermatol. 1997;6:214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1997.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smola H, Thiekotter G, Fusenig N E. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:417–429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konstantinova N V, Lemak N A, Duong D M, Chuang A Z, Urso R, Duvic M. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:385–391. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199802000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fusenig N E. In: The Keratinocyte Handbook. Leigh I, Lane E, Watt F M, editors. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1994. pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saiag P, Coulomb B, Lebreton C, Bell E, Dubertret L. Science. 1985;230:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.2413549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott K A, Wood E J, Karran E H. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curran S, Murray G I. J Pathol. 1999;189:300–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199911)189:3<300::AID-PATH456>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson N, Kahari V M. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:225–237. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher G J, Datta S C, Talwar H S, Wang Z Q, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees J J. Nature (London) 1996;379:335–339. doi: 10.1038/379335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann A R, Bridges B A. Br J Dermatol. 1990;35, Suppl. 122:115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb16136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van de Leun J. Photochem Photobiol. 1965;4:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1965.tb09760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg R J, Ruven H J, Sands A T, de Gruijl F R, Mullenders L H. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.1998.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berg R J, Rebel H, van der Horst G T, van Kranen H J, Mullenders L H, van Vloten W A, de Gruijl F R. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2858–2863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarasin A. Mutat Res. 1999;428:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chadwick C A, Potten C S, Nikaido O, Matsunaga T, Proby C, Young A R. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1995;28:163–170. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(94)07096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bruls W A G, Slaper H, van der Leun J, Berrens L. Photochem Photobiol. 1984;40:485–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1984.tb04622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barrandon Y. Dev Biol. 1993;4:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dumaz N, Drougard C, Sarasin A, Daya-Grosjean L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10529–10533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quilliet X, Chevallier-Lagente O, Eveno E, Stojkovic T, Destee A, Sarasin A, Mezzina M. Mutat Res. 1996;364:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(96)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng L, Quilliet X, Chevallier-Lagente O, Eveno E, Sarasin A, Mezzina M. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]