Abstract

Continental runoff is a major source of freshwater, nutrients and terrigenous material to the Arctic Ocean. As such, it influences water column stratification, light attenuation, surface heating, gas exchange, biological productivity and carbon sequestration. Increasing river discharge and thawing permafrost suggest that the impacts of continental runoff on these processes are changing. Here, a new optical proxy was developed and implemented with remote sensing to determine the first pan-Arctic distribution of terrigenous dissolved organic matter (tDOM) and continental runoff in the surface Arctic Ocean. Retrospective analyses revealed connections between the routing of North American runoff and the recent freshening of the Canada Basin, and indicated a correspondence between climate-driven changes in river discharge and tDOM inventories in the Kara Sea. By facilitating the real-time, synoptic monitoring of tDOM and freshwater runoff in surface polar waters, this novel approach will help understand the manifestations of climate change in this remote region.

Continental runoff influences surface ocean processes throughout the Arctic. Rivers discharge about 3,300 km3 yr−1 of buoyant freshwater to the Arctic Ocean1 where it sustains a halocline that isolates the upper 200-m layer from a warmer, saltier Atlantic layer2. This upper layer represents only 0.1% of the global ocean volume but receives 11% of global riverine discharge from a circumpolar drainage basin that encompasses over 10% of the world's land surface area. Riverine input is evident throughout the Arctic from low salinities and high concentrations of terrigenous dissolved organic matter (tDOM) in polar surface waters3,4. Arctic rivers discharge onto the world's largest continental shelves that surround and cover more than half of the Arctic Ocean area5. These river-influenced ocean margins are dominant features of the Arctic and important regions of sea-ice production, biological productivity, carbon sequestration and processes that drive biogeochemical cycles on a basin-wide scale.

The impact of rivers on the freshwater content and biogeochemistry of the Arctic Ocean is strongly influenced by the residence time of riverine inputs and their pathways to the North Atlantic Ocean. The average residence time of Arctic shelf water ranges from months to years depending on shelf region6,7. Variations in atmospheric forcing can affect residence time by dramatically altering continental runoff routing and distribution in the Arctic Ocean7,8. Climate-driven changes in runoff distribution have been linked to large inter-annual and decadal variations in the freshwater content of the Arctic Ocean, and these fluctuations have important ramifications for North Atlantic meridional overturning circulation9. Furthermore, changes in runoff routing through the Arctic Ocean can regulate the extent to which Arctic tDOM is incorporated into North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) and distributed in the global ocean4. Despite their global significance, continental runoff routing and distribution in the Arctic remain poorly understood and difficult to predict in this remote and under-sampled region of the global ocean. Here, a new optical proxy for tDOM implemented using remote sensing of ocean color facilitates the synoptic and retrospective monitoring of continental runoff in the Arctic Ocean, and provides a novel approach to assess climate-driven changes in the Arctic.

Results

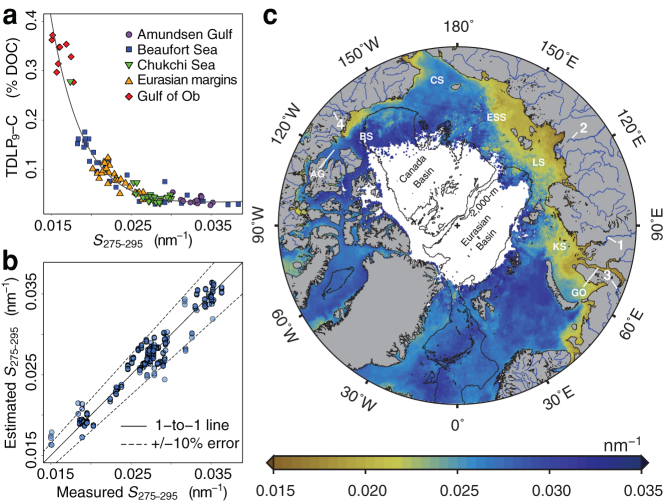

Dissolved lignin is well established as a biomarker of tDOM in oceanic waters10,11 and has been successfully applied as a tracer of riverine inputs in the Arctic Ocean3,4. However, its use relies on the collection of seawater samples and land-based laboratory analyses that prevent synoptic applications. Lignin is also an important chromophore in tDOM, a property that facilitates detection using optical properties. Here, we demonstrate that the spectral slope coefficient of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) between 275 and 295 nm (S275–295) is a practical and reliable optical proxy for dissolved lignin and tDOM across various river-influenced ocean margins of the Arctic Ocean12,13 (Fig. 1a). An increase in S275−295 is indicative of a decrease in the tDOM content of surface waters. Under the assumption that S275–295 behaves conservatively, an increase in S275–295 corresponds to a diminishing influence of continental runoff. Biological degradation has little effect on S275–29513,14 and photodegradation of tDOM in polar surface waters is not extensive4,15, thereby warranting the assumption and the use of S275–295 as a tracer of tDOM and freshwater runoff in river-influenced ocean margins of the Arctic.

Figure 1. The CDOM spectral slope coefficient, S275–295, as a tracer of riverine inputs in the Arctic Ocean.

(a) The relationship between S275–295 and dissolved lignin carbon yield (TDLP9-C) across various Arctic river-influenced ocean margins. (b) A performance evaluation of the S275–295 algorithm. On average, S275–295 can be estimated from ocean color within 4% of S275–295 values measured in situ. (c) Implementation of the algorithm using MODIS Aqua ocean color providing a pan-Arctic view of an August climatology (2002–2009) of S275–295. Increasing S275–295 values are indicative of a decreasing fraction of tDOM. The four largest Arctic rivers are labeled and ranked in order of decreasing discharge: Yenisei (1), Lena (2), Ob (3), and Mackenzie (4). River-influenced margins of the Arctic are labeled: Gulf of Ob (GO), Kara Sea (KS), Laptev Sea (LS), East Siberian Sea (ESS), Chukchi Sea (CS), Beaufort Sea (BS) and Amundsen Gulf (AG). The contour lines represent the 2000-m isobath.

The practicality of the S275–295 proxy resides in its amenability to remote sensing. The development of an empirical algorithm reveals that S275–295 can be estimated from ocean color with excellent and consistent accuracy (within ± 4%) over the broad range of water types and S275–295 values observed in the Arctic Ocean (Fig. 1b). The strong connection between S275–295 and ocean color in river-influenced ocean margins exists because the optical property S275–295 is an excellent tracer of tDOM13 and the gradients of ocean color in river-influenced ocean margins are primarily driven by the constituents of continental runoff. The S275–295 algorithm thus facilitates the synoptic and real-time monitoring of tDOM and freshwater runoff in the Arctic using ocean-color remote sensing.

Implementation of the S275–295 algorithm using MODIS Aqua ocean color provides the first pan-Arctic view of average tDOM distributions in river-influenced ocean margins during August 2002–2009 (Fig. 1c). The influence of the three largest Arctic rivers on tDOM distributions is evident along the entire Siberian margin. One of the most striking features is the overwhelming amount of tDOM in the Laptev and East Siberian Seas, indicating a large portion of Eurasian river tDOM and runoff is routed alongshore in an eastward direction. This observation is supported by measurements of high in situ concentrations of dissolved organic carbon of terrigenous origin in the East Siberian Sea in August 200816, and is consistent with shelf water residence times of several years in this region6,7. Low S275–295 values along the Alaskan coast in the Chukchi Sea depict the transport of Yukon River tDOM to the Arctic Ocean in the Alaska Coastal Current and indicate notable tDOM contributions by smaller Alaskan rivers (e.g., Noatak and Kobuk Rivers). Most of the runoff and tDOM from the Mackenzie River enters the Beaufort Sea and appears to be entrained in the gyre circulation of the southern Canada Basin. A relatively small fraction of the discharge from the Mackenzie River was routed to the Labrador Sea via the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA).

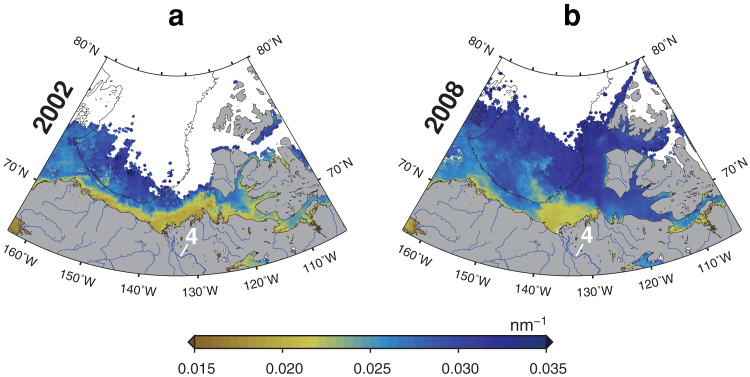

Assessment of inter-annual variability in tDOM distribution revealed a change in the routing of Mackenzie River discharge over the last decade (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4). The Mackenzie River outflow progressed from an alongshore, eastward path to the CAA in 2002 (Fig. 2a) to a cross-shelf, northwestward path to the Canada Basin since 2006 (Fig. 2b). This routing switch has important implications for the fate of North American runoff and tDOM. Routing through the CAA favors the export of North American tDOM to the Labrador Sea17. Although the magnitude of this export remains unknown, deep ocean convection in the Labrador Sea can sequester tDOM in North Atlantic Deep Water for centuries4. In contrast, routing to the Canada Basin contributes to longer-term storage of runoff and processing of tDOM within the Beaufort Gyre and Arctic Ocean4,15. This decadal shift to greater export of Mackenzie River runoff to the Canada Basin during 2006–2011 could contribute to less North American tDOM being sequestered in the deep ocean.

Figure 2. Inter-annual changes in the routing of Mackenzie River runoff.

(a) The Mackenzie River outflow in 2002, showing eastward transport of North American runoff to the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. (b) The Mackenzie River outflow in 2008, showing northwestward transport of North American runoff to the Canada Basin. A progressive switch from eastward to northwestward routing occurred between 2002 and 2011 (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4) and coincides with the rapid freshening of the Canada Basin. The S275–295 algorithm was implemented using 4-km resolution, yearly-binned, MODIS Aqua ocean color. The Mackenzie River is labeled (4). The contour line represents the 2000-m isobath and outlines the Canada Basin.

The routing of Mackenzie River outflow since 2006 coincides with observations of a rapid accumulation of freshwater in the Canada Basin. Freshening began in the 1990s and accelerated in the late 2000s18,19,20,21. The realization that a large accumulation of freshwater in the Canada Basin could impact global ocean circulation stimulated research to identify the freshwater sources and climatic forcing responsible for observed changes in salinity. Pacific water, ice-melt, precipitation and river runoff are distinct sources of freshwater to the Canada Basin. The relative contributions of these freshwater sources to the freshening are typically estimated using tracers (e.g. δ18O, alkalinity, salinity) or are indirectly calculated using complex models9,20,22,23,24,25. The lignin-based S275–295 proxy presented here substantiates the riverine origin of freshwater and provides a direct means to distinguish continental runoff from other freshwater sources using remote sensing.

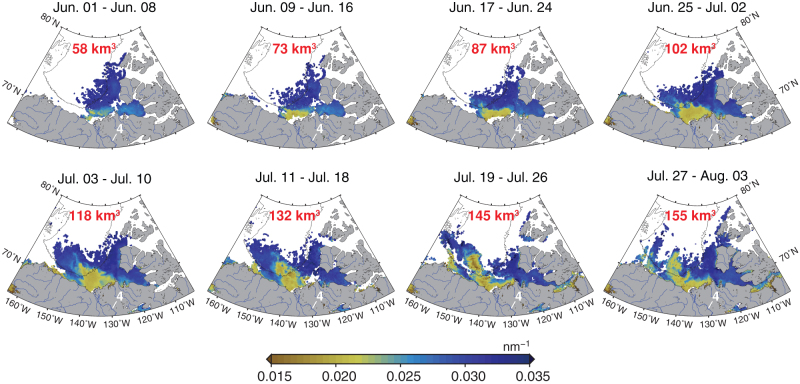

The acceleration of the Beaufort Gyre due to the strengthening of the Beaufort High26 and routing of Eurasian river runoff to the Canada Basin driven by the Arctic Oscillation9 are complementary and currently leading explanations for the freshening of the Basin27. The remotely sensed runoff distributions presented in this study (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4) further suggest the recurrent influx of Mackenzie River runoff to the Canada Basin in the late 2000s was also a significant source of freshwater to the Basin and contributed to the freshening. The temporal sequence of the Mackenzie River discharge in 2008 provides unambiguous evidence that the spring freshet was directly and rapidly injected into the Canada Basin during June and July (Fig. 3). In situ measurements of salinity, δ18O, and alkalinity from an independent study20 corroborate that Mackenzie River runoff was a minor source of freshwater to the Canada Basin in the early 2000s but increased in the southern part of the Basin in 2007.

Figure 3. Temporal sequence of the Mackenzie River freshet release into the Canada Basin during June and July 2008.

The S275–295 algorithm was implemented using 4-km resolution, 8-day-binned, MODIS Aqua ocean color acquired between June 1 and August 3. The discharge value (km3) displayed on each panel indicates the cumulative Mackenzie River discharge released between May 1 (start of the freshet) and the end of each 8-day period. The contour line represents the 2000-m isobath and delineates the Canada Basin. The Mackenzie River is labeled (4).

The contribution of North American runoff to the Canada Basin freshwater budget appears to be shifting in response to climatic forcing. A freshwater budget based on data from 2003–2004 estimated about 40% of North American runoff enters the Canada Basin22. The mean freshwater residence time in the Basin is about 10 years22, so this estimate is representative of the decade leading up to 2004. Although significant freshwater contributions from the Mackenzie River to the Basin were observed during that decade28, this estimate does not integrate the increasing contributions from North American runoff since 2006. The detailed progression of the 2008 Mackenzie River outflow indicated up to 155 km3 of Mackenzie freshwater was released into the Canada Basin in June and July alone (Fig. 3), indicating more than half of the discharge from the Mackenzie has been entering the Canada Basin since 2006. Increasing contributions of North American runoff to the Canada Basin are consistent with enhanced Ekman pumping resulting from the wind-driven spin-up of the Beaufort Gyre26 and therefore appear to result from recent trends in climate variability.

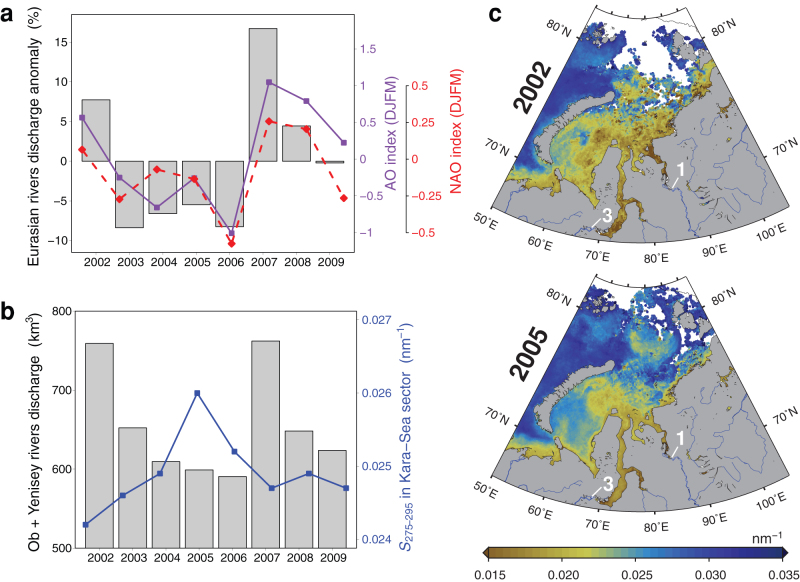

Discharge from major Arctic rivers has increased over the past decades in response to climate variability29,30,31. Climatic forcing of river discharge is evident between 2002 and 2009 from the strong correspondence between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) or Arctic Oscillation (AO) wintertime indices and the river discharge anomaly of Eurasian rivers (Fig. 4a). Manifestations of inter-annual discharge fluctuations in the Arctic Ocean are best illustrated in the Kara Sea, which receives inputs from the Ob and Yenisei rivers. The Kara Sea is a semi-enclosed margin that is largely ice-free during summer, which facilitates inter-annual comparisons of remotely sensed variables. Inter-annual comparisons revealed consistency between discharge from the Ob and Yenisei rivers and the average S275–295 value for the Kara-Sea sector (Fig. 4b). The correspondence between discharge and tDOM in the Kara Sea is particularly striking when comparing 2002 and 2005, which are representative of high and low discharge years between 2002 and 2009 (Fig. 4c). This demonstrates climate-driven changes in the tDOM inventory of the surface Arctic Ocean are traceable using this approach.

Figure 4. Climatic forcing of major Eurasian riverine inputs.

(a) The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) wintertime indices (DJFM: Dec-Jan-Feb-Mar) in relation to the combined discharge anomaly of the Yenisei, Lena and Ob rivers between 2002 and 2009. High NAO and AO indices are typically associated with higher precipitation over Northern Eurasia. River discharge is calculated as the cumulative discharge from May 1 to August 30, and the anomaly is relative to the 2002–2009 average. (b) Average S275–295 values for surface waters of the Kara Sea in relation to the combined discharge of the Yenisei and Ob rivers between 2002 and 2009. The S275–295 values for the Kara Sea were calculated as the average value in the region displayed in panel (c). River discharge is calculated as the cumulative discharge from May 1 to August 30. (c) Distributions of riverine inputs during high (2002) and low (2005) discharge years. The years correspond to low and high average S275–295 values observed in the Kara Sea between 2002 and 2009. The S275–295 algorithm was implemented using MODIS Aqua ocean color data averaged from May to October. The Yenisei and Ob rivers are labeled (1) and (3), respectively.

Discussion

The S275–295 proxy and algorithm presented in this study facilitate the real-time and synoptic monitoring of tDOM and freshwater runoff in surface polar waters. The foundation of the S275–295 proxy on the lignin biomarker is fundamental to the approach. The “terrigenous” attribute of lignin substantiates the riverine origin of dissolved organic matter and freshwater. Its “chromophoric” property, on the other hand, facilitates implementation with remote sensing. Although the Arctic remains one of the most challenging environments for remote sensing, it is also a region where remote sensing has much to offer given the logistical restrictions and high costs of field surveys, particularly on the Siberian shelves. The applicability of the approach will improve as the extent and duration of sea-ice cover decrease, allowing for greater spatial and temporal coverage.

New capabilities to monitor surface tDOM distributions will prove valuable for understanding future climate-driven changes in the biogeochemistry of the Arctic. Permafrost thawing and precipitation in drainage basins of Arctic rivers are projected to intensify with escalating atmospheric temperatures and thereby enhance the mobilization of soil organic matter to the Arctic Ocean32,33,34,35,36. The fate of this material and its effects on biogeochemical cycles will depend on its routing and residence time in polar surface waters4. Furthermore, processing of organic matter in surface waters is influenced by factors that are currently being altered by climate change (e.g., ice cover, water temperature). Multiyear records of remotely sensed tDOM distributions provide direct evidence of how the routing, inventory, storage and residence time of tDOM in surface polar waters change in response to climatic forcing. Such applications will thus provide crucial information for understanding the fate of immobilized soil organic matter and its impacts on biogeochemical cycles in this rapidly changing Arctic environment.

Finally, remote sensing of continental runoff provides useful insights about the sources of freshwater in the Arctic Ocean. Ice melt, precipitation and runoff are all increasing under the current climatic trends31,37, and are altering the freshwater budget of the Arctic Ocean. Remotely sensed runoff distributions provide direct evidence of continental runoff contributions to specific regions of the surface Arctic Ocean, and will thereby help understand the mechanisms responsible for future changes in the Arctic freshwater budget. It is important to remember, however, that the uncoupling of river water from its tDOM component during the winter freeze-thaw cycle38 hampers the use of this approach to assess year-to-year changes in freshwater runoff storage. Future applications will also likely include studying the influence of continental runoff on biological processes, such as primary production, in polar surface waters.

Methods

Surface water samples and data (n = 106) used to establish the relationship between S275–295 and TDLP9-C (Fig. 1a) were acquired during several field expeditions to the Arctic Ocean between 2005 and 2010, including the Amundsen Gulf, Gulf of Ob, and the Beaufort, Chukchi, Laptev and East Siberian Seas (Supplementary Fig. S1). Samples for DOC and CDOM were filtered onboard and analyzed in the home laboratory using high temperature combustion39 and a dual-beam UV-visible spectrophotometer12,13, respectively. Samples for dissolved lignin (1–10 L) were extracted onboard40 and analyzed using the cupric oxide oxidation method and gas chromatography with mass spectrometry41. DOC-normalized yields of nine lignin phenols (TDLP9-C) were calculated13, and the non-linear regression of TDLP9-C on S275–295 utilized the exponential function shown in equation (1),

where α = 2.7428, β = −245.5899, γ = 1.6669, and δ = −0.9932 are the derived regression coefficients.

The in situ measurements of ocean color (n = 236) and concurrent CDOM samples used in the S275–295 algorithm development (Fig. 1b) were collected during the Malina and ICESCAPE field expeditions (Supplementary Fig. S2). Multispectral remote-sensing reflectances, Rrs(λ), were derived for 5 wavelengths (λ = 443, 488, 531, 555 and 667 nm) from profiles made with a Biospherical Compact-Optical Profiling System (C-OPS)42, and the corresponding CDOM samples were collected and analyzed according to NASA standard protocols43. “Measured” S275–295 were calculated from CDOM absorption coefficient spectra, and regressed on Rrs(λ) using the multiple linear regression described in equation (2),

where α = −3.4567, β = 0.4299, γ = 0.0924, δ = −1.2649, ε = 0.8885, and ζ = −0.1025 are the derived regression coefficients. This data set covers a broad range of water types found in river-influenced ocean margins, including high-CDOM and sediment-laden coastal environments, productive waters at intermediate salinities and oligotrophic waters at higher salinities. The inclusion of data from the Chukchi Sea in summer (ICESCAPE) further demonstrates that the algorithm performs very well in areas where tDOM is relatively low and biogenic particles are abundant and variable. Similar accuracy of S275–295 retrievals was obtained using data collected seasonally in the northern Gulf of Mexico in various water types ranging from riverine to oligotrophic, thereby indicating that the approach used in the algorithm is robust.

MODIS Aqua data were accessed from the NASA ocean color website (http://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/). Monthly NAO and AO indices were acquired from the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory website (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/climateindices). The Mackenzie River discharge data were obtained from the Environment Canada Water Office website (http://www.wateroffice.ec.gc.ca). Eurasian river discharge was obtained from the ArcticRIMS website (http://rims.unh.edu/data.shtml).

Author Contributions

Development of the main concept, design of the figures and writing of the text were done by C.F. and R.B. The ICESCAPE and CFL samples were collected and analyzed by C.F. (DOC, CDOM, lignin). The Malina samples were collected by R.B. and analyzed by C.F. (lignin) and S.W. (CDOM). The NABOS samples were collected and analyzed by K.K. (DOC, lignin) and S.W. (CDOM). The Gulf-of-Ob samples were processed by C.F. (DOC, CDOM, lignin). S.H. collected and processed the remote-sensing reflectances and CDOM measurements used to develop the algorithm. M.B. and S.B. facilitated research on the CFL, Malina and ICESCAPE expeditions. C.F., R.B., K.K. and R.A. discussed the results and all authors commented on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of: 1) the Malina Scientific Program (http://malina.obs-vlfr.fr) funded by ANR (Agence nationale de la recherche), INSU-CNRS (Institut national des sciences de l'univers, Centre national de la recherche scientifique), CNES (Centre national d'études spatiales) and ESA (European Space Agency); 2) the Circumpolar Flaw Lead (CFL) study (http://www.ipy-api.gc.ca/pg_IPYAPI_029-eng.html) funded by the Government of Canada (IPY #96); 3) the Impacts of Climate on the Eco-Systems and Chemistry of the Arctic Pacific Environment (ICESCAPE) program (http://www.espo.nasa.gov/icescape/) funded by NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration); 4) the Nansen and Amundsen Basin Observational System (NABOS) project (http://nabos.iarc.uaf.edu/index.php) funded by the US-NSF (National Science Foundation), NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration), the ONR (Office of Naval Research) and JAMSTEC (Japan Marine Science and Technology Center). This work was directly supported by NSF grants 0713915 and 0850653 to R.B., NSF grants 0229302, 0425582, 0713991 to R.A., and NASA funding to S.H. We thank the following people: the crews of the USCGC Healy, CCGS Amundsen and Russian icebreaker Kapitan Dranitsyn for assistance with sample collection, Dr. Jolynn Carroll for collecting the Gulf-of-Ob samples, Vanessa Wright, Joaquin Chavez and Aimée Nealy for assisting S.H. with collection and analysis of Malina and ICESCAPE data, and Yuan Shen for DOC analysis of Malina samples.

References

- Rachold V. et al. in The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds Stein R., & MacDonald R. W.) Ch. 2 Modern Terrigenous Organic Carbon Input to the Arctic Ocean. 33–55 (Springer, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Aagaard K. & Carmack E. C. The Role of Sea Ice and Other Fresh Water in the Arctic Circulation. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 14485–14498 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl S., Benner R. & Amon R. M. W. Major flux of terrigenous dissolved organic matter through the Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 2017–2023 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Benner R., Louchouarn P. & Amon R. M. W. Terrigenous dissolved organic matter in the Arctic Ocean and its transport to surface and deep waters of the North Atlantic. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19, GB2025 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson M., Grantz A., Kristoffersen Y. & Macnab R. in The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds Stein R., & MacDonald R. W.) Ch. 1.1 Bathymetry and Physiography of the Arctic Ocean and its Constituent Seas. 1–6 (Springer, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser P., Bauch D., Fairbanks R. & Bönisch G. Arctic river-runoff: mean residence time on the shelves and in the halocline. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 41, 1053–1068 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald R. W., Sakshaug E. & Stein R. in The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds Stein R., & MacDonald R. W.) Ch. 1.2 The Arctic Ocean: Modern Status and Recent Climate Change. 6–12 (Springer, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bauch D. et al. Exchange of Laptev Sea and Arctic Ocean halocline waters in response to atmospheric forcing. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C05008 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Morison J. et al. Changing Arctic Ocean freshwater pathways. Nature 481, 66–70 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers-Schulte K. J. & Hedges J. I. Molecular evidence for a terrestrial component of organic matter dissolved in ocean water. Nature 321, 61–63 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl S. & Benner R. Distribution and cycling of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nature 386, 480–482 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Fichot C. G. & Benner R. A novel method to estimate DOC concentrations from CDOM absorption coefficients in coastal waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L03610 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Fichot C. G. & Benner R. The spectral slope coefficient of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (S275–295) as a tracer of terrigenous dissolved organic carbon in river-influenced ocean margins. Limnol. Oceanogr 57, 1453–1466 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Helms J. R. et al. Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr 53, 955–969 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger S. et al. Photomineralization of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in Arctic coastal waters from 1979 to 2003: Interannual variability and implications of climate change. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 20, GB4005 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Alling V. et al. Nonconservative behavior of dissolved organic carbon across the Laptev and East Siberian seas. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB4033 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. A., Amon R. M. W., Stedmon C., Duan S. & Louchouarn P. The use of PARAFAC modeling to trace terrestrial dissolved organic matter and fingerprint water masses in coastal Canadian Arctic surface waters. J. Geophys. Res. 114, G00F06 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Proshutinsky A. et al. Beaufort Gyre freshwater reservoir: State and variability from observations. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C00A10 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- McPhee M. G., Proshutinsky A., Morison J. H., Steele M. & Alkire M. B. Rapid change in freshwater content of the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L10602 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Kawai M. et al. Surface freshening of the Canada Basin, 2003–2007: River runoff versus sea ice meltwater. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C00A05 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B. et al. An assessment of Arctic Ocean freshwater content changes from the 1990s to the 2006–2008 period. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 58, 173–185 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Kawai M., McLaughlin F. A., Carmack E. C., Nishino S. & Shimada K. Freshwater budget of the Canada Basin, Arctic Ocean, from salinity, δ18O, and nutrients. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C01007 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R. W., McLaughlin F. A. & Carmack E. C. Fresh water and its sources during the SHEBA drift in the Canada Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 49, 1769–1785 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Serreze M. C. et al. The large-scale freshwater cycle of the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. 111, C11010 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser P. et al. Decrease of river runoff in the upper waters of the Eurasian Basin, Arctic Ocean, between 1991 and 1996: Evidence from δ18O data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1289 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Giles K. A., Laxon S. W., Ridout A. L., Wingham D. J. & Bacon S. Western Arctic Ocean freshwater storage increased by wind-driven spin-up of the Beaufort Gyre. Nature Geosciences 5, 194–197 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mauritzen C. Oceanography: Arctic freshwater. Nature Geosciences 5, 162–164 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R. W., Carmack E. C., McLaughlin F. A., Falkner K. K. & Swift J. H. Connections among ice, runoff and atmospheric forcing in the Beaufort Gyre. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 2223–2226 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. J. et al. Increasing river discharge to the Arctic Ocean. Science 298, 2171–2173 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiklomanov A. I. & Lammers R. B. Record Russian river discharge in 2007 and the limits of analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 045015 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- McClelland J. W., Déry S. J., Peterson B. J., Holmes R. M. & Wood E. F. A pan-arctic evaluation of changes in river discharge during the latter half of the 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L06715 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Benner R., Benitez-Nelson B., Kaiser K. & Amon R. M. W. Export of young terrigenous dissolved organic carbon from rivers to the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L05305 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Frey K. E. & Smith L. C. Recent temperature and precipitation increases in West Siberia and their association with the Arctic Oscillation. Polar Res. 22, 287–300 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Frey K. E. & Smith L. C. Amplified carbon release from vast West Siberian peatlands by 2100. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L09401 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Ping C.-L. & Macdonald R. W. Mobilization pathways of organic carbon from permafrost to arctic rivers in a changing climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L13603 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Amon R. M. W. et al. Dissolved organic matter sources in large Arctic rivers. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 94, 217–237 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Serreze M. C. et al. Observational Evidence of Recent Change in the Northern High-Latitude Environment. Climatic Change 46, 159–207 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Amon R. M. W. in The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean (eds Stein R., & MacDonald R. W.) Ch. 4 The Role of Dissolved Organic Matter for the Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean. 83–99 (Springer, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Benner R. & Strom M. A critical evaluation of the analytical blank associated with DOC measurements by high-temperature catalytic oxidation. Mar. Chem. 41, 153–160 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Louchouarn P., Opsahl S. & Benner R. Isolation and quantification of dissolved lignin from natural waters using solid-phase extraction and GC/MS. Anal. Chem. 72, 2780–2787 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser K. & Benner R. Characterization of lignin by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry using a simplified CuO oxidation method. Anal. Chem. 84, 459–464 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S., Morrow J. & Matsuoka A. The 1% and 1 cm perspective in deriving and validating AOP data products. Biogeosciences Discuss 9, 9487–9531 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pegau S. et al. in Ocean Optics Protocols For Satellite Ocean Color Sensor Validation, Revision 4 (eds James Mueller L., Giulietta Fargion S., & Charles McClain R.). Vol. IV, Inherent Optical Properties: Instruments, Characterizations, Field Measurements and Data Analysis Protocols. (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures