Abstract

Background

Anthropometric measures such as body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) have differential associations with incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) and mortality. We examined the associations of BMI and WC with various CKD complications.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 2853 adult participants with CKD in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999-2006. The associations of BMI and WC (both as categorical and continuous variables) with CKD complications such as anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, metabolic acidosis, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension were examined using logistic regression models while adjusting for relevant confounding variables.

Results

When examined as a continuous variable, an increase in BMI by 2 kg/m2 and WC by 5 cm was associated with higher odds of secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension among those with CKD. CKD participants with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 have higher odds of hypoalbuminemia and hypertension than CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2. CKD participants with a high WC (>102 cm in men and >88 cm in women) have higher odds of hypoalbuminemia and hypertension and lower odds of having anemia than CKD participants with a low WC. CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and high WC (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC) was not associated with CKD complications.

Conclusions

Anthropometric measures such as BMI and WC are associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension among adults with CKD. Higher WC among those with BMI <30 kg/m2 is not associated with CKD complications.

Keywords: Obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, chronic kidney disease

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and obesity are major public health problems (1-3). Epidemiological investigations have identified obesity as an independent risk factor for the development of CKD and the progression of CKD to ESRD in the general population (4). Potential mechanisms that might mediate these associations include insulin resistance, increased inflammation, higher oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction seen among those who are obese (5). While body mass index (BMI), an anthropometric measure of whole body adiposity has been associated with the development of CKD, previous studies that examined the association of BMI and mortality showed paradoxica results in dialysis and renal transplant recipients (6, 7). Even though widely used, a major limitation of the BMI measure is its inability to differentiate fat mass and muscle mass which may have opposite associations with mortality (8, 9).

Waist circumference (WC), a measure of visceral or abdominal adiposity is associated with subclinical inflammation independent of BMI (10). In the general population, while some studies report that measures of abdominal adiposity are better predictors of cardiovascular disease and mortality, others claim that central adiposity measures such as WC and WHR do not provide additional prognostic information than BMI alone (11-13). In those with CKD, population-based studies suggest that measures of abdominal adiposity such as WC and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), rather than BMI, are better predictors of adverse outcomes such as mortality (14). However, the association between the different measures of adiposity such as BMI and WC and complications arising from CKD has not been explored in previous studies. We hypothesized that obesity is associated with different CKD complications and that anthropometric measures such as BMI and WC have differential associations with CKD complications. As such, we studied the associations of waist circumference and BMI with CKD complications such as anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, metabolic acidosis, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension among a nationally representative sample of US adults.

Methods

Study population

We examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally representative, complex and multistage probability of the US civilian, non-institutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The National Centers for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board approved the study protocol and each participant provided written informed consent. Participants in NHANES were interviewed in their homes and underwent a standardized physical examination in a mobile examination center. Self-reported information on demographics, socioeconomic status, health conditions, health behaviors and routine site of healthcare were obtained during the interview. The examination component consisted of medical, dental, and physiological measurements, as well as laboratory tests administered by highly trained medical personnel. The four, 2-year cycles of the continuous NHANES 1999-2000, 2001-2002, 2003-2004 and 2005-2006 were combined for this analysis. Two thousand eight hundred and fifty three participants who met the following criteria were included: 20 years of age and older who underwent medical examination, those who were not pregnant, had BMI and WC measured, had a BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2, had serum creatinine and albumin/creatinine ratio results, and those who were not on dialysis, and had eGFR ≥15 ml/min/1.73m2.

Measures

Kidney disease and comorbidities

Participants with stage 1-4 CKD who were not on dialysis were included (Stage 1-2 CKD: those with urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio of ≥30–299 mg/g [microalbuminuria] and ≥300 mg/g [macroalbuminuria]) with estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or stage 3-4 CKD: eGFR 15-59 ml/min/1.73 m2). eGFR was calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equations using calibrated creatinine (15, 16). Serum creatinine levels were corrected for the 1999-2000 and 2005-2006 surveys as suggested in the NHANES serum creatinine documentation (16). Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) was calculated from spot urine albumin and creatinine samples obtained. Diabetes was defined as self-reported if ever told by a doctor that the participant had “diabetes or borderline diabetes”.

Hypercholesterolemia was defined as the presence of total cholesterol >200 mg/dl and/or use of cholesterol lowering medications. Liver disease was defined by the answer “yes” to the question, “Have you ever been told that you had any liver condition”.

Adiposity measures

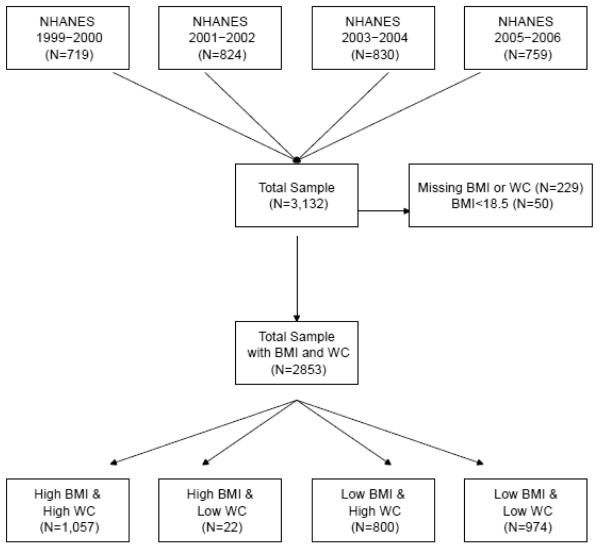

Height and weight measurements were collected by trained health technicians using standardized techniques and equipment during the health examination conducted in each survey period. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest with the participant standing. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the measured height in meters squared and participants were classified as obese if they had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Waist circumference was categorized as high risk for men with a measured WC >102 cm and women with a measured WC >88 cm. All others were considered low risk (17). We also considered four different categories based on BMI and WC data: a) BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC, b) BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and low WC, c) BMI <30 kg/m2 and high WC and d) BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Details of how CKD participants from different NHANES surveys were included in this study

CKD complications

Anemia was defined as hemoglobin (Hb) <13.5 g/dl for males and Hb <12 g/dl for females (18). A serum bicarbonate level <21 meq/L was defined as the presence of metabolic acidosis and PTH >70 pg/ml was defined as secondary hyperparathyroidism (19). Hyperphosphatemia was defined as the presence of serum phosphorus >4.5 mg/dl (19). Hypoalbuminemia was defined as a serum albumin level <4 g/dl. Hypertension was defined as the presence of systolic blood pressure (SBP) >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >90 mm Hg or the use of an antihypertensive medication.

Statistical analysis

Demographics, comorbidities, and CKD complications were compared between participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2 and with high and low waist circumference (WC >102 cm in males and >88 cm in females) using t-tests for continuous variables and Rao-Scott Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Results were reported as mean ± standard error (SE) for continuous variables and % (95% CI) for categorical variables. We examined the associations between different anthropometric measures such as BMI (for every 2 kg/m2 increase) and WC (for every 5 cm increase) and CKD complications while adjusting for age, gender, African American race, diabetes, hypertension, liver disease (for hypoalbuminemia outcome only), smoking, log UACR, and eGFR.

Logistic regression analysis was also used to assess the associations between individual CKD complications and BMI ≥30 kg/m2 while adjusting for above mentioned variables. A sensitivity analysis that compared BMI ≥30 kg/m2 to BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 was also conducted. Similarly, logistic regression analysis was used to assess the associations between individual CKD complications and a high WC (>102 cm in males and >88 cm in females) while adjusting for the relevant confounding variables mentioned above. BMI and WC were not included in these models due to collinearity (unweighted correlation = 0.87).

In addition, logistic regression analysis categorized participants as: a) BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC (obese based on both criteria) vs. participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC (non-obese based on both criteria); and b) participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and high WC vs. participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC while adjusting for variables mentioned above was also conducted. We could not conduct a separate analysis for those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and low WC vs. participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC due to the small sample size in the former (n=22).

All analyses were performed using survey procedures with SAS version 9.2 for Unix (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), which account for the sampling design of NHANES and appropriately weight participants in statistical models. Graphs were produced using R version 2.12.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant characteristics

BMI ≥30 kg/m2 vs. BMI <30 kg/m2

CKD participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were younger (58.0 [0.7] years vs. 62.7 [0.7] years) and had more Non-Hispanic blacks (14.6% vs. 9.0%) than CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2. A higher proportion of CKD participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 had diabetes (p <0.001) (Table 1). The mean WC of CKD participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was 115.6 (0.6) cm compared to 92.4 (0.3) cm among CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 (p <0.001). Mean eGFR was 75.1 ml/min/1.73m2 for those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 vs. 71.2(1.0) ml/min/1.73m2 for the BMI <30 kg/m2 group (p=0.003). UACR was higher among those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 than among those with BMI <30 kg/m2 (p =0.03). Table 1 lists additional participant characteristics based on their BMI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who were categorized as obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2) based on BMI criteria

| Variable | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (n=1079) |

BMI <30 kg/m2 (n=1774) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age,years(mean ± SE) | 58.0(0.7) | 62.7(0.7) | <0.001 |

| Male gender,%(95% CI) | 43.6(39.6, 47.5) | 42.6(39.8, 45.3) | 0.68 |

| Race,%(95% CI) | <0.001 | ||

| Non-hispanic White | 68.5(63.9, 73.1) | 74.7(71.0, 78.5) | |

| Non-hispanic black | 14.6(11.5, 17.7) | 9.0(7.0, 11.0) | |

| Mexican American | 6.5(4.5, 8.5) | 5.5(3.8, 7.1) | |

| Other Hispanic | 6.2(3.3, 9.1) | 4.6(2.2, 7.0) | |

| Other | 4.2(2.0, 6.4) | 6.2(4.4, 8.0) | |

| Household Income,%(95% CI) | |||

| < $ 20,000 | 29.4(25.7, 33.2) | 27.1(23.2, 31.0) | 0.55 |

| $20,000 - $44,999 | 34.4(29.9, 38.9) | 34.0(30.8, 37.1) | |

| $45,000 - $74,999 | 19.5(15.3, 23.7) | 22.7(18.9, 26.5) | |

| ≥ $75,000 | 16.7(12.9, 20.6) | 16.3(13.2, 19.4) | |

| Diabetes,%(95% CI) | 28.1(24.8, 31.3) | 16.1(13.8, 18.4) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac disease,%(95% CI) | 13.1(10.8, 15.5) | 16.1(13.6, 18.6) | 0.09 |

| Hyperlipidemia,%(95% CI) | 68.9(65.0, 72.7) | 68.4(65.6, 71.3) | 0.83 |

| Smoking,%(95% CI) | 16.1(13.5, 18.8) | 19.6(17.1, 22.0) | 0.052 |

| BMI(kg/m2)(mean ± SE) | 35.9(0.3) | 25.2(0.1) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference(cm)(mean ± SE) | 115.6(0.6) | 92.4(0.3) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2(mean ± SE) | 75.1(1.1) | 71.2(1.0) | 0.003 |

| CKD stage(%,95%CI) | <0.001 | ||

| Stages 1-2* | 58.8(54.7, 63.0) | 49.3(46.0, 52.6) | |

| Stage 3a(eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 29.1(25.2, 32.9) | 36.9(34.1, 39.7) | |

| Stage 3b(eGFR 30-45 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 9.4(7.2, 11.6) | 11.6(9.9, 13.2) | |

| Stages 4(eGFR 15-29 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 2.7(1.7, 3.7) | 2.3(1.5, 3.1) | |

| UACR(mg/g)(mean ± SE) | 191.2(23.7) | 137.7(11.3) | 0.033 |

| Hypoalbuminemia (albumin <4g/dl) | 27.1(24.0, 30.3) | 17.7(15.1, 20.2) | <0.001 |

| Anemia (%, 95% CI) | 11.0(8.8, 13.1) | 12.7(10.4, 15.1) | 0.23 |

| Metabolic acidosis(serum bicarbonate <21 mmol/l)(%, 95% CI) |

7.3(4.7, 10.0) | 5.8(4.0, 7.6) | 0.29 |

| SHPT(PTH >70 pg/ml)(%, 95% CI) | 22.2(18.0, 26.3) | 17.8(14.2, 21.5) | 0.11 |

| Hyperphosphatemia(serum phosphorus >4.5 mg/dl)(%, 95% CI) |

5.8(3.9, 7.8) | 6.1(4.6, 7.6) | 0.80 |

| Hypertension(%,95%CI) | 70.6(66.8, 74.4) | 57.9(54.9, 60.9) | 0.11 |

| CRP(mean ± SE) | 0.7(0.04) | 0.5 (0.04) | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index, WC: Waist Circumference, SE: standard error, UACR: urine albumin to creatinine ratio, SHPT: secondary hyperparathyroidism;

- Stage 1-2 CKD includes those with eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and micro or macroalbuminuria.

High vs. low waist circumference (>102 cm in males and >88 cm in females)

CKD participants with high WC were older (62.2 [0.6] years vs. 58.6[1.0] years) with a lesser proportion of males (37.9% vs. 52.8%) than CKD participants with a low WC. A higher proportion of CKD participants with high WC had diabetes, and hyperlipidemia (p <0.001) (Table 2). The mean BMI of CKD participants with high WC was 32.3 (0.2) kg/m2 compared to 23.9 (0.1) kg/m2 among CKD participants with low WC). Mean eGFR was 71.2 ml/min/1.73m2 for those with high WC vs. 75.7(1.3) ml/min/1.73 m2 for those with low WC (p=0.004). UACR was similar between those with high and low WC (p=0.21). Table 2 lists additional participant characteristics based on their WC.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants who were categorized as obese and non-obese based on WC criteria

| Variable | High WC (n=1857) |

Low WC (n=996) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years(mean±SE) | 62.2(0.6) | 58.6(1.0) | 0.002 |

| Male gender,%(95%CI) | 37.9(35.0, 40.8) | 52.8(48.5, 57.1) | <0.001 |

| Race,%(95%CI) | 0.33 | ||

| Non-hispanic White | 72.7(68.7, 76.6) | 71.4(67.0, 75.8) | |

| Non-hispanic black | 11.6(9.1, 14.2) | 10.4(8.2, 12.5) | |

| Mexican American | 5.8(4.1, 7.5) | 6.0(4.1, 8.0) | |

| Other Hispanic | 5.1(3.0, 7.3) | 5.5(2.7, 8.4) | |

| Other | 4.7(3.0, 6.5) | 6.7(4.1, 9.3) | |

| Household Income,%(95%CI) | |||

| <$20,000 | 29.9(26.1, 33.6) | 24.4(20.6, 28.2) | 0.011 |

| $20,000 - $44,999 | 34.9(31.7, 38.1) | 32.6(28.3, 36.9) | |

| $45,000 - $74,999 | 20.4(17.2, 23.6) | 23.3(18.7, 27.9) | |

| ≥$75,000 | 14.8(11.8, 17.8) | 19.7(15.8, 23.5) | |

| Diabetes,%(95%CI) | 24.9(22.2, 27.5) | 13.1(10.0, 16.1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac disease,%(95%CI) | 15.7(13.6, 17.8) | 13.5(10.1, 16.7) | 0.28 |

| Hyperlipidemia,%(95%CI) | 72.3(69.5, 75.2) | 61.3(56.9, 65.8) | <0.001 |

| Smoking,%(95%CI) | 15.7(13.5, 17.9) | 22.9(19.5, 26.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI(kg/m2)(mean±SE) | 32.3(0.2) | 23.9(0.1) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference(cm)(mean±SE) | 109.2(0.5) | 87.0(0.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR,ml/min/1.73m2(mean±SE) | 71.2(0.9) | 75.7(1.3) | 0.004 |

| CKD stage(%,95%CI) | 0.05 | ||

| Stages 1-2* | 51.5(48.1, 54.8) | 56.2(51.9, 60.5) | |

| Stage 3a(eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 34.1(31.3, 36.9) | 33.2(29.4, 36.9) | |

| Stage 3b(eGFR 30-45 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 11.6(9.7, 13.6) | 8.9(6.9, 10.9) | |

| Stages 4(eGFR 15-29 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 2.8(2.1, 3.6) | 1.7(0.9, 2.6) | |

| UACR(mg/g)(mean ± SE) | 168.3(16.6) | 140.8(15.5) | 0.21 |

| Hypoalbuminemia(albumin <4g/dl) | 24.5(22.2, 26.9) | 15.4(12.6, 18.2) | <0.001 |

| Anemia(%, 95% CI) | 11.4(9.5, 13.3) | 13.2(10.4, 16.0) | 0.23 |

| Metabolic acidosis(serum bicarbonate <21 mmol/l)(%, 95% CI) |

6.1 (4.3, 7.9) | 7.0 (3.9, 10.1) | 0.58 |

| SHPT(PTH >70 pg/ml)(%, 95% CI) | 20.9(17.8, 24.0) | 16.6(11.9, 21.3) | 0.12 |

| Hyperphosphatemia(serum phosphorus >4.5 mg/dl)(%, 95% CI) |

6.7(4.9, 8.4) | 4.7(3.3, 6.1) | 0.08 |

| Hypertension(%,95%CI) | 69.8(66.8, 72.9) | 49.6(45.0, 54.2) | <0.001 |

| CRP(mean±SE) | 0.6(0.03) | 0.5(0.06) | 0.02 |

BMI: body mass index, WC: Waist Circumference, SE: standard error, UACR: urine albumin to creatinine ratio, SHPT: secondary hyperparathyroidism; High WC: WC >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women

- Stage 1-2 CKD includes those with eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and micro or macroalbuminuria.

Associations between anthropometric measures and CKD complications

Continuous variable

An increase in BMI by 2 kg/m2 was associated with increased odds of having secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension (Table 3). Similarly, an increase in WC by 5 cm was associated with increased odds of having secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension but also with lower odds of having anemia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between CKD complications and BMI and WC when examined as a continuous measure

| CKD complications* | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2increase | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.06 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Hypoalbuminemia** | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2increase | 1.13 (1.09, 1.18) | <0.001 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic acidosis | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2increase | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.57 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.94 |

| Secondary hyperparathyroidism | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2increase | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) | 0.01 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 1.08 (1.02, 1.15) | 0.01 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2increase | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 0.86 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 1.00 (0.94, 1.04) | 0.93 |

| Hypertension*** | ||

| BMI per 2 kg/m2 increase | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | <0.001 |

| WC per 5cm increase | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, log UACR and eGFR.

Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, eGFR,log UACR, liver disease and hypertension.

Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, log UACR and eGFR.

Categorical analyses

BMI ≥30 kg/m2 vs. BMI <30 kg/m2

CKD participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 have higher odds of hypoalbuminemia and hypertension than CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 when adjusted for relevant confounding variables (Table 4). There was a non-significant increase in the odds for secondary hyperparathyroidism among those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (Table 4). There were no associations between BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and hyperphosphatemia, metabolic acidosis and anemia. A sensitivity analysis that compared BMI ≥30 kg/m2 to BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 confirmed these results

Table 4.

Odds of having CKD complications among obese participants based on different BMI and WC categories

| CKD complications* | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 0.77 (0.56, 1.07) | 0.12 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 0.73 (0.55, 0.97) | 0.03 |

| Hypoalbuminemiay** | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 1.78 (1.34, 2.36) | <0.001 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 1.54(1.20, 1.98) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic acidosis | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 1.17 (0.73, 1.88) | 0.51 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 0.92 (0.53, 1.60) | 0.76 |

| Secondary hyperparathyroidism | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 1.38 (0.96, 1.98) | 0.08 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 1.24 (0.82, 1.86) | 0.31 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 0.86 (0.57, 1.35) | 0.56 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 1.11 (0.74, 1.67) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension*** | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (vs. BMI <30 kg/m2) | 2.41 (1.89, 3.07) | <0.001 |

| High WC vs. Low WC | 2.19 (1.65, 2.90) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, log UACR and eGFR.

Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, eGFR, log UACR, liver disease and hypertension.

Adjusted for age, African American race, gender, smoking, diabetes, log UACR and eGFR.

High vs. low waist circumference

CKD participants with high WC have higher odds of hypoalbuminemia and hypertension, and lower odds of having anemia than CKD participants with low WC when adjusted for relevant confounding variables (Table 4). There were no associations between high WC and hyperphosphatemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and metabolic acidosis.

BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC vs. BMI <30 kg/m2and low WC

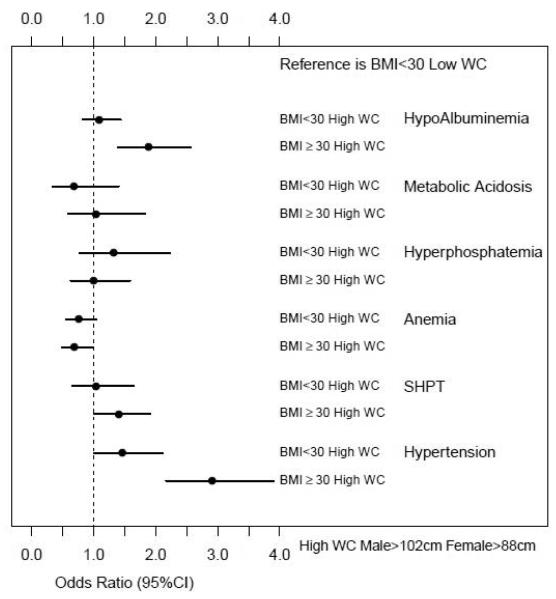

CKD participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC (who would meet both the criteria of obesity) have higher odds of secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia and hypertension than participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC when adjusted for relevant confounding variables (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Odds of having CKD complications for participants with different BMI and WC categories

BMI <30 kg/m2 and high WC vs. BMI <30 kg/m2and low WC

CKD participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and high WC was not associated with any increased likelihood of CKD complications when compared to participants with BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC when adjusted for relevant confounding variables (Figure 2).

Discussion

Our analysis of representative US adults with kidney disease shows that the anthropometric obesity measures such as BMI and WC are associated with different CKD complications. These associations are similar when examined as continuous variables. However, when examined as a categorical variable based on standard definitions of obesity based on BMI and WC measures, there were differential associations. Participants with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC (obese based on both criteria) had higher odds of secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia and hypertension than participants who have low WC and BMI <30 kg/m2 (non-obese based on both criteria). In addition, among those with BMI <30 kg/m2, presence of high WC was not associated with any CKD complications.

Previous studies have explored the associations between various adiposity measures and incident CKD. Secondary analysis of the Cardiovascular Health Study and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study showed that WHR but not BMI was associated with incident CKD and mortality (20). In a non-diabetic cohort, WC and BMI but not WHR were associated with lower eGFR (21). Studies exploring the associations of different anthropometric measures with kidney disease progression and mortality are limited. Secondary analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed that the associations of obesity with mortality differed by the presence or absence of CKD suggesting that kidney disease does not reverse the metabolic effects of obesity (22). Recently, Kramer et al. reported higher mortality rates for waist circumference >94 cm in men and >80 cm in women, while no such associations were noted for higher BMI categories among 5,805 CKD participants (14). Our study adds to this growing body of evidence regarding the utility of these different adiposity measures in the CKD population. In addition, these findings highlight the different results that might be obtained when examining these anthropometric variables as continuous and categorical variables.

Associations between BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and secondary hyperparathyroidism have been reported previously, but the associations of BMI and WC with other CKD complications have not been explored. Kovesdy et al. reported that higher BMI levels were associated with higher PTH levels among non-dialysis dependent patients (23). Similarly, secondary analysis of the Kidney Early Evaluation Program data showed that higher BMI was associated with high PTH levels independent of confounding variables (24). Waist circumference data was not available in these studies. In addition to the findings from previous studies, we found higher odds of having PTH >70 pg/ml with both increasing BMI and WC. Some proposed explanations that may explain these associations include lower 25(OH)D levels and lower physical activity (thus lower sun exposure) noted among those with higher BMI and WC. In addition, the decreased bioavailability of vitamin D due to its deposition in adipocytes among those who are obese might also contribute to the higher rates of secondary hyperparathyroidism (25).

When examined as both continuous and categorical variables, participants with a high BMI and WC had higher odds of having hypoalbuminemia among CKD participants. Obesity is a state of inflammation and thus hypoalbuminemia might reflect the higher inflammatory burden among those who are obese rather than nutritional status alone (26, 27). We also examined whether presence of BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC were also associated with highly sensitive C - reactive protein (Hs-CRP) levels. Hs-CRP levels were higher among those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 and high WC and this data supports the inflammation hypothesis (Tables 1 and 2). We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis by defining hypoalbuminemia as serum albumin <3.5 g/dl but the relatively small number of participants precluded this analysis.

As expected, the presence of higher BMI and WC were associated with increased odds of having hypertension among CKD participants, and this data is similar to that seen in the general population. However, there was a negative association between high WC and anemia noted in this analysis. To our knowledge, no studies have reported associations between anemia and obesity in both CKD and non-CKD population except that a population-based study reported no significant associations between anemia and obesity in the absence of CKD (28). The exact mechanisms that might explain these associations are unclear at present and these associations should be re-examined and confirmed in future studies.

BMI data is readily available in clinical settings and whether WC details provide additional prognostic details relating to CKD complications in this population is unclear. Hence, we examined the associations between BMI <30 kg/m2 and High WC and CKD complications. Our results suggest that BMI data alone might be sufficient to predict CKD complications in those with lower BMI. We could not conduct an analysis among participants with BMI >30 kg/m2 and low WC vs. BMI <30 kg/m2 and low WC to examine the utility of BMI alone due to the small sample size.

One strength of this study was the inclusion of a nationally representative sample with adequate representation of various ethnic groups in the United States. This analysis is subject to limitations that include the cross-sectional study design of NHANES surveys that precludes the opportunity for studying temporal associations. Also, the use of a single UACR measurement in the NHANES surveys might lead to misclassification of CKD, especially among participants with early-stage CKD. Further, the number of participants with advanced CKD is minimal and whether these associations exist among those with advanced kidney disease need to be examined in future studies. We also did not have body composition measures such as DEXA or computed tomography measures which would provide more detailed insight into the role of the body composition.

In summary, anthropometric measures such as BMI and WC are associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension among those with CKD. Higher WC among those with BMI <30 kg/m2 is not associated with CKD complications .These associations suggest the need for closely monitoring the development of complications relating to CKD among those who are obese.

Footnotes

Disclosure: SDN is supported by a career development award from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (Grant #RR024990). JPK is supported by the National Institutes of Health - RO1 DK089547. JDS is supported by NIH/NIDDK (R01 DK085185) and investigator initiated-grant support from PhRMA foundation, Genzyme and Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation. MJS is supported by K24 DK078204. The contents of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors have no relevant financial interest in the study.

References

- 1.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, Farzadfar F, Riley LM, Ezzati M. Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index): National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navaneethan SD, Kirwan JP, Arrigain S, Schreiber MJ, Sehgal AR, Schold JD. Overweight, obesity and intentional weight loss in chronic kidney disease: NHANES 1999-2006. Int.J.Obes.(Lond) 2012 Jan 31; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann.Intern.Med. 2006;144:21–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin KA, Kramer H, Bidani AK. Adverse renal consequences of obesity. Am.J.Physiol.Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F685–96. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00324.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovesdy CP, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Rosivall L, Novak M, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Molnar MZ, Mucsi I. Body mass index, waist circumference and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am.J.Transplant. 2010;10:2644–2651. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Salahudeen AK, Kilpatrick RD, Horwich TB. Survival advantages of obesity in dialysis patients. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2005;81:543–554. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artero EG, Lee DC, Ruiz JR, Sui X, Ortega FB, Church TS, Lavie CJ, Castillo MJ, Blair SN. A prospective study of muscular strength and all-cause mortality in men with hypertension. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2011;57:1831–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wijnhoven HA, Snijder MB, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, Deeg DJ, Visser M. Region-specific fat mass and muscle mass and mortality in community-dwelling older men and women. Gerontology. 2012;58:32–40. doi: 10.1159/000324027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapice E, Maione S, Patti L, Cipriano P, Rivellese AA, Riccardi G, Vaccaro O. Abdominal adiposity is associated with elevated C-reactive protein independent of BMI in healthy nonobese people. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1734–1736. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bombelli M, Facchetti R, Sega R, Carugo S, Fodri D, Brambilla G, Giannattasio C, Grassi G, Mancia G. Impact of body mass index and waist circumference on the long-term risk of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiac organ damage. Hypertension. 2011;58:1029–1035. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor AE, Ebrahim S, Ben-Shlomo Y, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Yarnell JW, Wannamethee SG, Lawlor DA. Comparison of the associations of body mass index and measures of central adiposity and fat mass with coronary heart disease, diabetes, and all-cause mortality: a study using data from 4 UK cohorts. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2010;91:547–556. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coutinho T, Goel K, Corrêa de Sá D, Kragelund C, Kanaya AM, Zeller M, Park JS, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Cottin Y, Lorgis L, Lee SH, Kim YJ, Thomas R, Roger VL, Somers VK, Lopez-Jimenez F. Central obesity and survival in subjects with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of the literature and collaborative analysis with individual subject data. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2011;57:1877–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer H, Shoham D, McClure LA, Durazo-Arvizu R, Howard G, Judd S, Muntner P, Safford M, Warnock DG, McClellan W. Association of waist circumference and body mass index with all-cause mortality in CKD: The REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) Study. Am.J.Kidney Dis. 2011;58:177–185. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.02.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration): A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann.Intern.Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selvin E, Manzi J, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Lacher DA, Levey AS, Coresh J. Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988-1994, 1999-2004. Am.J.Kidney Dis. 2007;50:918–926. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization [Last accessed June 23 2012]; http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501491_eng.pd.

- 18.National Kidney Foundation Anemia Guidelines [Last accessed June 23, 2012]; http://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_anemia/index.htm. 2006.

- 19.National Kidney Foundation [Last accessed June 23, 2012]; http://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_bone/index.htm. 2003.

- 20.Elsayed EF, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Griffith JL, Kurth T, Salem DN, Levey AS, Weiner DE. Waist-to-hip ratio, body mass index, and subsequent kidney disease and death. Am.J.Kidney Dis. 2008;52:29–38. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton JO, Gray LJ, Webb DR, Davies MJ, Khunti K, Crasto W, Carr SJ, Brunskill NJ. Association of anthropometric obesity measures with chronic kidney disease risk in a non-diabetic patient population. Nephrol.Dial.Transplant. 2012;27:1860–1866. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan BC, Murtaugh MA, Beddhu S. Associations of body size with metabolic syndrome and mortality in moderate chronic kidney disease. Clin.J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2007;2:992–998. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04221206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovesdy CP, Ahmadzadeh S, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Obesity is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism in men with moderate and severe chronic kidney disease. Clin.J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2007;2:1024–1029. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01970507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saab G, Whaley-Connell A, McFarlane SI, Li S, Chen SC, Sowers JR, McCullough PA, Bakris GL. Kidney Early Evaluation Program Investigators. Obesity is associated with increased parathyroid hormone levels independent of glomerular filtration rate in chronic kidney disease. Metabolism. 2010;59:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2000;72:690–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramkumar N, Cheung AK, Pappas LM, Roberts WL, Beddhu S. Association of obesity with inflammation in chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. J.Ren.Nutr. 2004;14:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eustace JA, Astor B, Muntner PM, Ikizler TA, Coresh J. Prevalence of acidosis and inflammation and their association with low serum albumin in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ausk KJ, Ioannou GN. Is obesity associated with anemia of chronic disease? A population-based study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2356–2361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]