Abstract

In response to invading microorganisms, insect β-1,3-glucan recognition protein (βGRP), a soluble receptor in the hemolymph, binds to the surfaces of bacteria and fungi and activates serine protease cascades that promote destruction of pathogens by means of melanization or expression of antimicrobial peptides. Here we report on the NMR solution structure of the N-terminal domain of βGRP (N-βGRP) from Indian meal moth (Plodia interpunctella), which is sufficient to activate the prophenoloxidase (proPO) pathway resulting in melanin formation. NMR and isothermal calorimetric titrations of N-βGRP with laminarihexaose, a glucose hexamer containing β-1,3 links, suggest a weak binding of the ligand. However, addition of laminarin, a glucose polysaccharide (~ 6 kDa) containing β-1,3 and β-1,6 links that activates the proPO pathway, to N-βGRP results in the loss of NMR cross-peaks from the backbone 15N-1H groups of the protein, suggesting the formation of a large complex. Analytical ultra centrifugation (AUC) studies of formation of N-βGRP:laminarin complex show that ligand-binding induces self-association of the protein:carbohydrate complex into a macro structure, likely containing six protein and three laminarin molecules (~ 102 kDa). The macro complex is quite stable, as it does not undergo dissociation upon dilution to sub-micromolar concentrations. The structural model thus derived from the present studies for N-βGRP:laminarin complex in solution differs from the one in which a single N-βGRP molecule has been proposed to bind to a triple helical form of laminarin on the basis of an X-ray crystallographic structure of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose complex [Kanagawa, M., Satoh, T., Ikeda, A., Adachi, Y., Ohno, N., and Yamaguchi, Y. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29158–29165]. AUC studies and phenoloxidase activation measurements carried out with the designed mutants of N-βGRP indicate that electrostatic interactions involving Asp45, Arg54, and Asp68 between the ligand-bound protein molecules contribute in part to the stability of N-βGRP:laminarin macro complex and that a decreased stability is accompanied by a reduced activation of the proPO pathway. Increased β-1,6 branching in laminarin also results in destabilization of the macro complex. These novel findings suggest that ligand-induced self-association of βGRP:β-1,3-glucan complex may form a platform on a microbial surface for recruitment of downstream proteases, as a means of amplification of the initial signal of pathogen recognition for the activation of the proPO pathway.

Keywords: pathogen recognition; innate immunity; β-1,3-glucan; βGRP

INTRODUCTION

βGRPs, also called Gram-negative bacteria binding proteins (GNBPs), are a family of insect pathogen recognition receptors that bind to β-1,3-glucan, a structural component of fungal cell walls and bacterial surfaces (1–6). The protein-carbohydrate binding event triggers activation of serine protease cascades leading to the activation of the proPO pathway in the hemolymph and intracellular Toll signaling (7,8). The activated proPO pathway produces melanin that encapsulates pathogenic microorganisms, whereas the Toll pathway results in the expression of antimicrobial peptides/proteins.

βGRPs share a conserved primary structure comprising an amino-terminal carbohydrate-binding domain (N-βGRP) and a carboxyl-terminal β-1,3-glucanase-like domain. N-βGRP binds to curdlan, a linear water-insoluble β-1,3-glucan polysaccharide, and to laminarin, a water-soluble β-1,3-glucan polysaccharide containing β-1,6 branches (1,9). P. interpunctella N-βGRP mixed with laminarin generates a significant synergistic activation of the proPO pathway (9). N-βGRP also induces aggregation of microorganisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli, albeit less effectively than does the full-length protein (9). Aggregation of pathogens in vivo may create a superior trigger for activating biochemical cascades of cellular immunity (9) or may provide a platform to assemble effector complexes (10). To gain insight into the molecular mechanism of such pathogen recognition events requires, as a first step, characterization of the structural basis and consequences of binding of β-1,3-glucan by N-βGRP.

Three-dimensional structures have been reported for N-βGRP from three insect species, Bombyx mori (11,12), Drosophila melanogaster (13) and P. interpunctella (12): all three N- βGRPs adopt a common immunoglobulin-like fold with two sheets forming a β-sandwich (Figure 1A). However, different models have been proposed for the binding of β-1,3-glucan by N-βGRP. In the model based on the solution structure of B. mori N-βGRP, as determined by means of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, the β-1,3-glucan binding site is located on the concave sheet (strands A, B and E) (11), while in the models based on the X-ray crystal structure of ligand-free D. melanogaster GNBP3 N-domain (13) and that of P. interpunctella N-βGRP complexed with laminarihexaose (12), the binding site is confined to the convex sheet (strands C, C′, F, G and G′). Furthermore, these three models do not provide any clues for understanding the molecular basis of the synergistic activation of the proPO pathway by β-1,3-glucan and N-βGRP.

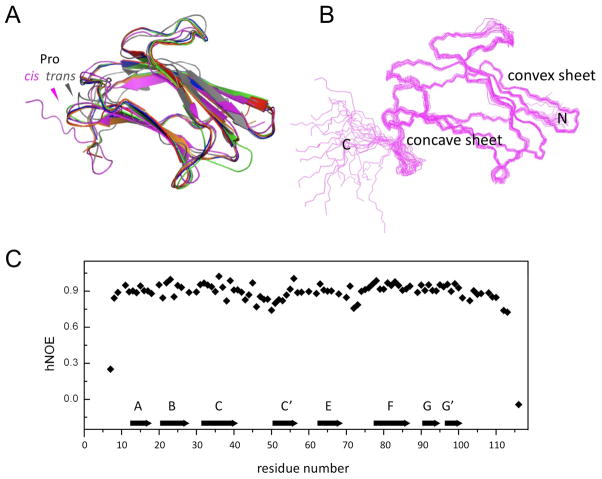

Figure 1.

(A) Superimposition of ribbon structures of N-βGRP from several insects: P. interpunctella - purple, 2KHA (NMR, current work); B. mori - gray, 2RQE [NMR; (11)]; D. melanogaster - green, 3IE4 [X-ray; (13)]; B. mori (laminarihexaose-bound) – orange, 3AQX [X-ray; (12)]; P. interpunctella - blue, 3AQY [X-ray; (12)]; P. interpunctella (laminarihexaose-bound) - red, 3AQZ [X-ray; (12)]; The NMR structure of P. interpunctella N-βGRP reported here differs from that of the B. mori protein (11) in the configuration of a Pro, as indicated. (B) Ensemble of twenty lowest-energy structures of P. interpunctella N-βGRP (2KHA). (C) A plot of backbone heteronuclear {15N}-1H NOE values vs. residue number for P. interpunctella N-βGRP. Pro residues do not give rise to {15N}-1H NOEs. A couple of C-terminal residues had hetero NOE peak intensities barely above the noise level. Each β-strand is represented by an arrow.

In the present work, we describe the NMR solution structure determination of P. interpunctella N-βGRP (N-terminal region of 118 residues) and mapping of the β-1,3-glucan binding site. We have characterized the binding of laminarihexaose, and that of laminarin, to N-βGRP by NMR, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), analytical ultracentrifugation studies (AUC), site-directed mutagenesis, and prophenoloxidase activity measurements. Our results demonstrate, for the first time, ligand-induced self-association of N-βGRP:β-1,3-glucan complex. This process has a significant contribution from electrostatic interactions between N-βGRP molecules in the complex. Reduction in the extent of self-association between N-βGRP:β-1,3-glucan complex molecules leads to a decrease in the rate of proPO activation by the macro complex. Thus it is suggested that such a protein:carbohydrate macro complex formation is a structural initiation signal for serine protease cascade activation of insect immune response and a likely prerequisite for aggregation of microorganisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Laminarin from Laminaria digitata was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (L9634, St. Louis, MO), and its β-1,3 to β-1,6 cross-link number ratio was 7 (14). Laminarihexaose and curdlan (a water-insoluble β-1,3-glucan) were from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland). A much more branched laminarin from Eisenia bicyclis with a β-1,3 to β-1,6 cross-link number ratio of 3 (15) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan).

Protein Expression and Purification

The DNA sequence of P. interpunctella N-βGRP was cloned via BamHI/HindIII sites into Invitrogen pPROEX HTb plasmid (9). The resulting recombinant protein contains an N-terminal hexahistidine tag followed by a TEV protease cleavage site before the N-βGRP sequence. Expression and purification of His6-N-βGRP was performed as described previously (9) with a slight modification. His6-N-βGRP was expressed in E. coli BL21 cells by induction with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside and purified using a Ni2+affinity column. The hexahistidine tag was cleaved by incubating His6- N-βGRP with His6-TEV protease (GE Helthcare), and the resultant mixture was passed through a Ni2+ affinity column to remove the cleaved hexahistidine tag, the TEV protease and uncleaved protein. Purity of N-βGRP was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the amino acid sequence of recombinant N-βGRP was confirmed by mass spectrometry. The recombinant protein had five extra N-terminal and seven extra C-terminal residues from the vector used. Proteins uniformly labeled either with 15N or with both 13C and 15N were produced by growing E. coli in M9 medium containing 15N-ammonium chloride and either D-glucose or uniformly 13C-labeled D-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), respectively.

N-βGRP containing mutation D45A or D45K was prepared according to the instructions of QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing and mass spectrometry of the purified protein.

NMR Spectroscopy

A typical solution sample of N-βGRP used for three-dimensional NMR experiments was 1.7 – 2.0 mM uniformly 13C/15N-labeled protein in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. NMR data were collected at 25°C using a Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe at Structural Biology Center, University of Kansas. The data sets were processed using NMRPipe (16) and analyzed using Sparky (17). A series of standard 2D- and 3D-NMR spectra was collected for backbone and side-chain resonance assignments and structural constraint measurements (18). These include 2D 15N-HSQC and 13C-HSQC, 3D CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, HN(CO)CA, HNCA, CCCONH, HCCCONH, HCCH-TOCSY, 15N-edited TOCSY, 15N-edited NOESY, and 13C-edited NOESY. An additional 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC data set was gathered from the 15N-labeled sample in order to identify HN-HN contacts. Sequence-specific backbone 1H, 15N, and 13C resonance assignments were made from an analysis of the 3D NMR data sets, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, HN(CO)CA, and HNCA. Side-chain resonances were assigned using the data from 3D CCCONH, HCCCONH, HCCH-TOCSY, and 15N-edited TOCSY. Unambiguous NOE constraints were manually assigned using 3D 15N-edited and 13C-edited NOESY spectra. Dihedral constraints for the backbone torsion angles (ϕ, ψ) were obtained using the software TALOS (19). Hydrogen bond constraints were employed for β-stand regions based on the NOE patterns and the chemical shift index prediction of the secondary structure (20). Structures of N-βGRP were calculated by a simulated annealing procedure using CNS (21). One hundred structures were calculated from which twenty lowest-energy structures were chosen for the final structural ensemble.

For NMR titration experiments, 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected of 0.5–1.0 mM 15N-labeled N-βGRP in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) at 25°C. Laminarihexaose or laminarin solutions (3 mM and 1mM, respectively) prepared in the same buffer and then added stepwise to the protein sample (0.5 mM). The chemical shift difference between ligand-free and ligand-saturated protein was calculated for each backbone NH group as [(ΔH2+(ΔN/5)2)/2]1/2.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded with a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc.) equipped with dual monochromators. The experiments were performed using a 1 cm path length 3.5 ml quartz cuvette. The samples were excited at 295 nm, and emissions were measured between 300 and 400 nm to monitor Trp fluorescence.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were conducted with an Optima XL-I ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc. Brea, CA) using an An-60 Ti rotor at 20°C with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3) buffer containing 50 mM NaCl (22). Sedimentation was monitored by absorbance or interference optics using double-sector aluminum cells with a final loading of 400 μl per sector. Sedimentation was performed at 49,000 rpm with scans made at 5 min intervals. Data were analyzed using DCDT+ software version 1.16 (www.jphilo.mailway.com). Sedimentation coefficients were calculated using g(s*) and dc/dt fitting functions in DCDT+ software. Buffer density and viscosity were calculated by SEDNTERP version 1.08 (www.jphilo.mailway.com). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a standard to account for effects of changes in solution density and viscosity when high concentrations of laminarin or laminarihexaose were used. The partial specific volume of a protein was calculated from its amino acid composition using SEDNTERP (0.7306 ml/g for N-βGRP at 20°C). The partial specific volume used for laminarin was 0.622 ml/g (23).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC measurements were carried out using MCS-ITC system (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) at 30°C (24). Recombinant N-βGRP and laminarin solutions were dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 50 mM NaCl. Laminarihexaose was directly dissolved in the buffer. All solutions were degassed before use. A typical experiment consisted of 20 injections of 10 μl laminarin or laminarihexaose solution (1.67 mM) into 1.38 ml protein solution. The heat of dilution of laminarin or laminarihexaose solution upon injection into the buffer solution was subtracted from the experimental titration data. Baseline corrections and integration of the calorimeter signals were performed using the software, Origin (MicroCal).

Curdlan Pull-down Assay

The procedure described by Fabrick et al. (9) was employed. Briefly, for each assay, 20 μg of purified protein (βGRP-N wide type, D45A, or D45K, respectively) was incubated with 0.5 mg of curdlan for 10 min. The protein-curdlan mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant corresponding to the unbound fraction was saved. The bound protein was eluted from curdlan by heating at 95°C for 5 min in SDS sample buffer. Equal volumes of purified, unbound and bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining.

Activation of the ProPO Pathway

A method as described by Ma and Kanost (2) and Fabrick et al. (4) was used, incorporating the modified protocol recently developed by Laughton and Siva-Jothy (25) to follow proPO activation in the absence or presence of laminarin. Briefly, 10 μl of recombinant proteins (0.4 mg/ml) was incubated with 5 [l of buffer or laminarin (10 mg/ml) and mixed with 5 μl of Manduca sexta plasma. The volume of each sample well was brought up to 130 μl with sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, 20 μl of 30 mM dopamine hydrochloride was added and phenoloxidase activity was determined by measuring absorbance at 490 nm. The phenoloxidase activity was presented as the change in milli-absorbance unit per minute. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Homogeneity of N-βGRP

The homogeneity of extensively purified N-βGRP was characterized by AUC. The sedimentation analysis of N-βGRP exhibited a homogeneous species with an S20, w value of 1.90 S corresponding to a weight average molecular weight of 14,500 by dc/dt analysis--a value in good agreement with the calculated mass of 14,601 Da. N-βGRP sedimentation pattern remained the same for a 1.7 mM solution (data not shown), thus indicating that N-βGRP existed as a monomer in solution at concentrations used for NMR experiments.

N-βGRP Solution Structure and Mapping of β-1,3–Glucan Binding-Site

The monomer structure of N-βGRP was determined using solution NMR methods (Figure 1B). The chemical shifts of backbone and side-chain 1H, 15N, and 13C nuclei of backbone were assigned by the application of standard multi-dimensional heteronuclear NMR methods (26). Upfield Cγ chemical shift and downfield Cβ chemical shift of Pro19, together with the strong NOE correlation between its Hα and Hα of preceding Tyr18, indicate that the peptide bond between Tyr18 and Pro19 adopts a cis conformation, consistent with the reported crystal structures (12,13), but in contrast to the trans conformation reported for the corresponding Pro in the solution structure of B. mori N-βGRP (11). The heteronuclear steady-state {15N}-1H NOE values are sensitive to the dynamics of the peptide NH bonds on a sub-nanosecond time scale (27). For residues Val8-Thr110, the average value of heteronuclear NOE is 0.84. The decreased NOE values observed for the N- and C- terminal regions reflect their relatively increased flexibility (Figure 1C).

Structural statistics for the twenty lowest-energy structures are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. We have identified the eight β-strands according to the standard immunoglobulin nomenclature (28): Three β-strands, A (Lys13-Ile17), B (Gly21-Pro27) and E (Arg63-Asp68), comprise the concave sheet; β-strands C (Ser32-Leu40), C′ (His51-Ile56), F (Lys78-Ile86), G (Gly91-Gln94) and G′ (Gly97-Thr100) comprise the convex sheet. Strands G and G′ are split by a kink (Asp95-Gln96).

Two long loops, C–C′ and E–F, have relatively higher flexibility than the strands as indicated by their slightly lower heteronuclear NOE values. However, the large number of inter-residue 1H-1H NOE distance constraints observed for residues in these two loops indicates that the loops are ordered and fairly rigid (Figure 1B), and hence are unlikely to undergo a large conformational change suggested by Mishima et al. (13). Furthermore, we measured the intensity of fluorescence emitted by tryptophans, among which Trp81 is located on the strands F and shielded by loop C–C′, before and after addition of laminarin to the protein sample, and found no change, thus ruling out any conformational changes for the C–C′ and E–F loops brought about by laminarin-binding. Interestingly, the crystal structure of P. interpunctella N-βGRP complexed with laminarihexaose (12) also shows no conformational alteration for these loops.

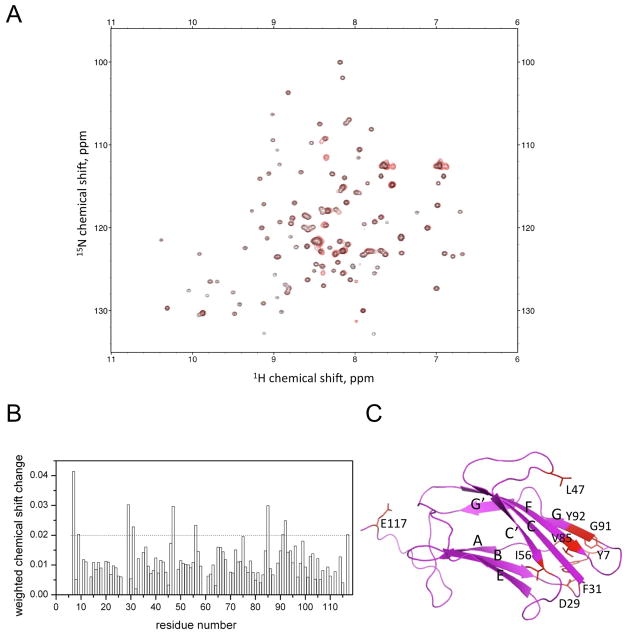

Effect of β-1,3-glucan binding on N-βGRP structure was characterized by titrating laminarihexaose, a β-1,3-linked glucose hexamer, into a solution of N-βGRP and monitoring the NMR cross-peaks of the protein backbone 15N-1H groups (Figure 2A & B). The perturbed residues are mainly localized on the convex sheet (Figure 2C), consistent with the hexasaccharide-binding site identified in the crystal structure of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose complex (12). The crystal structure shows that this region interacts with three laminarihexaose molecules, which led the authors to propose that N-βGRP binds to a triple helical structure of laminarin (12). However, to date no structural data are available for laminarin which is a branched polysaccharide. The X-ray fiber diffraction data collected for the linear β-1,3 polysaccharide, curdlan, have been interpreted to be indicative of a single-helical or a triple- helical structure, depending upon the hydration state of the polysaccharide (29, 30). In the presence of water, the diffraction data have been shown to be consistent only with a single-helix structure (29).

Figure 2.

Mapping of ligand-binding site on P. interpunctella N-βGRP by NMR titration of 1H-15 laminarihexaose at 25°C, pH 6.5: (A) N HSQC spectra of N-βGRP (0.5 mM) in the absence (black) or presence (red) of laminarihexaose (3 mM); (B) Chemical shift changes undergone by the backbone 15N-1H groups; the weighted average of chemical shift changes of an 15N-1H group was calculated by using the formula, [(ΔH2+(ΔN/5)2)/2]1/2, where ΔH and ΔN represent 1H and 15N chemical shift change, respectively; (C) Residues undergoing a chemical shift perturbation of > 0.02 ppm upon laminarihexaose titration are shown in red.

ITC experiments did not detect any heat exchange for the titration of laminarihexaose (up to 1.6 mM) into N-βGRP (78 μM; data not shown). This result is consistent with weak laminarihexaose - N-βGRP interactions, as suggested by the NMR data (Figure 2A & B).

Interactions between N-βGRP and Laminarin

Laminarin is a water-soluble oligosaccharide containing both β-1,3 and β-1,6 glycosidic bonds, and the number of β-1,6 glycosidic bonds varies depending upon the source. L. digitata laminarin used in this work has a β-1,3/β-1,6 glycosidic bond ratio of 7 (14). It shows a broad mass distribution (up to 7,505 Da) with major mass spectral peaks in the 3932 – 4580 Da region as obtained by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figure 1), consistent with the work of Barral et al. (31). Sedimentation velocity analysis of laminarin gave an S20, w value of 1.02 S, which yielded an apparent molecular weight of 4.5 kDa by dc/dt analysis. At a high concentration (5mg/ml), laminarin had a similar S value, which suggests that laminarin does not associate/aggregate by itself. Young et al. determined an average molecular weight of 7,700 Da for laminarin from light-scattering experiments (32). For the purpose of calculating molarities of laminarin solutions used in our work, we adopted a value of 6 kDa for the molecular weight, as provided by the supplier (Sigma Aldrich).

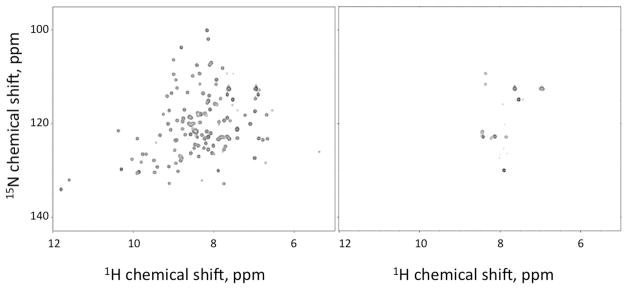

When laminarin was titrated into N-βGRP, nearly all the cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum broadened to a noise level (Figure 3). The NMR sample still remained clear with no precipitation. These observations indicate that in the presence of laminarin, N-βGRP forms a higher order, water-soluble structure. The results also suggest that the binding-site identified for laminarihexaose could interact with the surface structure of a carbohydrate polymer. The few cross-peaks that still remained after addition of laminarin to N-βGRP arise from flexible side-chain NH groups and peptide NH groups of some terminal residues.

Figure 3.

1H-15N HSQC spectra of N-βGRP (0.5 mM) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of laminarin (1 mM) at 25°C, pH 6.5.

Binding of laminarin to N-βGRP was characterized using ITC (Supplementary Figure 2). Because of the heterogeneity in laminarin as well as self-association of the resulting protein:carbohydrate complex, a likely cooperative process, the ITC data, although very similar to those of earlier studies (12,13), were not fit to any simple binding equilibrium. Qualitatively, the ITC data provided evidence for the binding of laminarin by N-βGRP, an exothermic process.

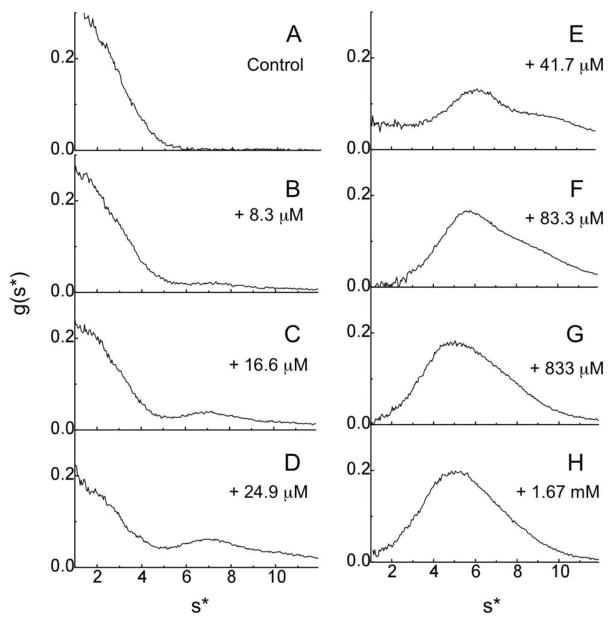

Interaction between N-βGRP and laminarin was characterized by sedimentation velocity analysis using absorption optics, which detects the distribution of the protein (Figure 4): As the concentration of laminarin added to a fixed concentration of N-βGRP (26.2 μM) increased from 8.3 to 24.9 μM, the concentration of free N-βGRP at 1.9 S decreased and a broad peak appeared between 4 and 9 S. With further increase in laminarin concentration (83.3 μM), nearly all of N-βGRP bound to laminarin and a major peak appeared at 5.5 S. A 20-fold excess of laminarin (1.87 mM) caused a slight decrease in S value (5.1 S) with a shoulder at ~8 S. A g(s*) fitting analysis yielded an average molecular weight of ~95 kDa for the 5.5 S species, a value that is remarkably greater than would be expected for a complex that contains one molecule of N-βGRP and three molecules of laminarin. Laminarin contains at least 30 glucose units, and thus each laminarin molecule could bind multiple N-βGRP molecules. However, the sedimentation profile around 5.5 S region changed only in a limited way even after addition of 20-fold excess of laminarin (1.87 mM). This suggests that formation of the 5.5 S species involves not only protein- carbohydrate interactions, but also protein-protein interactions. Because N-βGRP or laminarin alone does not oligomerize in solution, these results indicate that binding of laminarin causes self-association of N-βGRP:laminarin complex. Based on the sedimentation coefficient rule (33), which equates the ratio of average molecular weights of two proteins to the ratio of their sedimentation coefficients raised to the power of 3/2, the shoulder at ~8 S may be attributed to a higher order complex that is about twice the size of the 5.5 S macro complex. Similar association profiles were observed for the titration of laminarin into M. sexta N-βGRP (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of addition of varying concentrations of laminarin on N-βGRP, as monitored by sedimentation velocity experiments: Sedimentation profiles of N-βGRP (26.2 μM) in the absence (A) or presence of different levels of laminarin (B–H). Sedimentation at 49,000 rpm and 20 °C was monitored by measuring absorbance at 280 nm.

AUC experiments were similarly performed to monitor the effect of laminarihexaose on N-βGRP (Supplementary Figure 3): When 54 μM N-βGRP was mixed with 1.0 mM laminarihexaose, the g(s*) vs s* plot of N-βGRP displayed no significant change, consistent with a weak-binding of the ligand. At a higher concentration of the mixture, 234 μM N-βGRP and 14.1 mM laminarihexaose, a faster sedimenting species appeared in the 3–5 s* region, and with 1.4 mM N-βGRP and 26 mM laminarihexaose, the sedimentation profile shifted further to a higher s* region. The s* value range (3 – 5 S) of the faster sedimenting species falls close to that s* value of BSA (66.5 kDa, 4.3 S). These results suggest that high concentrations of laminarihexaose can mildly induce self-association of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose complex. It is of interest to note that D. melanogaster GNBP3 N-terminal domain does not bind to laminaritetraose (6), laminariheptaose or laminarihexaose (13). In contrast, several glucan-binding modules belonging to families other than GBM39, to which N-βGRP belongs, possess high binding affinities for hexasaccharides (34).

Self-association of N-βGRP:Laminarin Complex

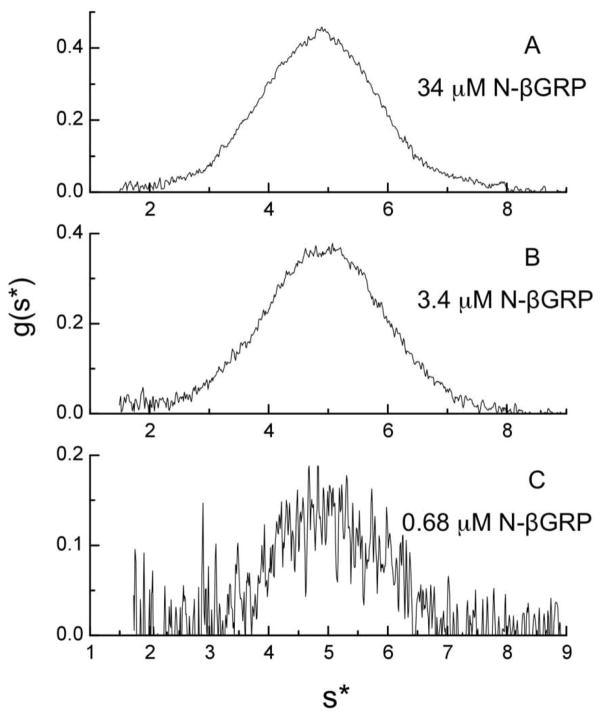

The stability of the macro-assembly of N-βGRP:laminarin complex was assessed by dilution analysis: AUC experiments (Figure 5) with three different concentrations of N-βGRP at a constant N-βGRP:laminarin ratio of 1:22.9 reveal that the s* profile of N-βGRP:laminarin complex was unchanged at 5 S even after 50-fold dilution (from 34.0 μM to 0.68 μM of the protein). This result indicates that the macro complex does not undergo dissociation at submicromolar concentrations due to strong protein-protein and protein-carbohydrate interactions. Sedimentation velocity experiments were also performed with the more branched E. bicyclis laminarin (Supplementary Figure 4): While 83.3 μM L. digitata laminarin with a β-1,3/β-1,6 ratio of 7 was sufficient for nearly complete conversion of N- βGRP (26 μM) into the 5.5 S protein:carbohydrate macro complex, a much higher concentration (0.8 mM) of E. bicyclis laminarin with a β-1,3/β-1,6 ratio of 3 was required for the macro complex formation. We infer that increased β-1,6 branching reduces the carbohydrate-binding strength of N-βGRP and thus the stability of the protein:carbohydrate macro complex.

Figure 5.

Effect of dilution on N-βGRP:laminarin complex as monitored by sedimentation velocity profiles: (A) 34 μM N-βGRP and 780 μM laminarin at 280 nm; (B) 3.4 μM N-βGRP and 78 μM laminarin at 220 nm; (C) 0.68 μM N-βGRP and 15.6 μM laminarin at 205 nm. The concentration ratio of N-βGRP:laminarin was maintained at 1:22.9. Sedimentation was carried out at 49,000 rpm and 20°C.

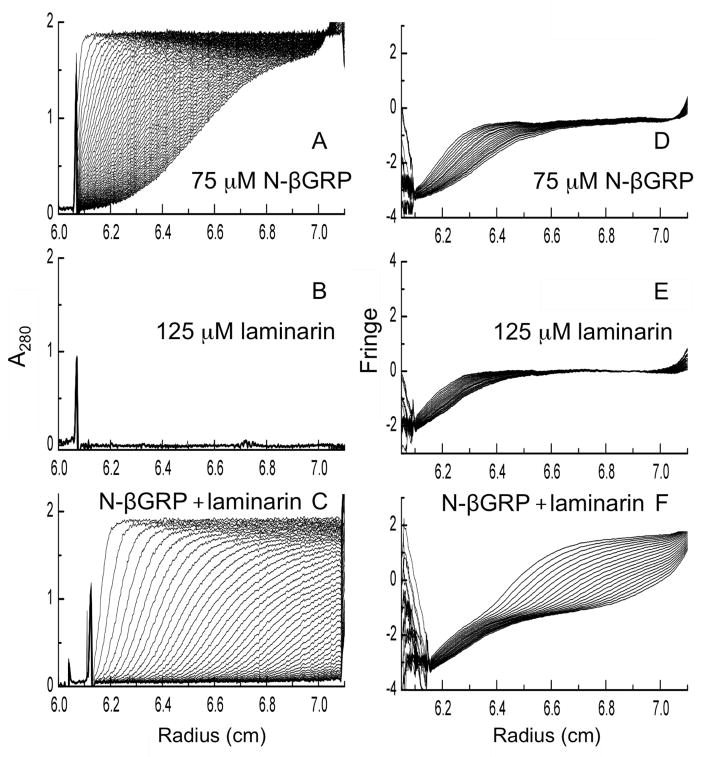

To determine the stoichiometry of N-βGRP:laminarin complex, we performed sedimentation velocity analysis using interference optics. The sedimentation of both N-βGRP and laminarin could be monitored, as these water-soluble molecules affect the refractive index of the solution. Fringe displacements caused by sedimentation provide a measure of weight concentration of sedimenting species (35). Sedimentation boundaries were compared between 75 μM N-βGRP and a mixture of 75 μM N-βGRP and 125 μM laminarin (Figure 6). Fringe displacement of N-βGRP alone was 2.5 arbitrary units, and that of the N-βGRP:laminarin complex (the faster species than either N-βGRP or laminarin alone) was 2.9. By using refractive indices of protein [(dn/dc) × 103 = 0.186 ml/mg] and dextran [(dn/dc) × 103 = 0.151 ml/mg], the weight ratio of N- β GRP:laminarin in the complex was calculated to be approximately 1:0.20, which equals 2:0.92 as a molar ratio. This is consistent with each laminarin (L) molecule binding two N-βGRP (P) molecules to form a P2L complex. Thus, the 5.5 S species is likely to be a trimer of P2L (~ 102 kDa; Figure 7A).

Figure 6.

Sedimentation velocity profiles for N-βGRP, laminarin and their mixtures, as monitored at 49,000 rpm and 20°C by absorbance at 280 nm (A–C) and interference optics (D–F) at 5 min. intervals: 75 μM N-βGRP (A & D) and 125 μM laminarin (B & E) were sedimented separately or together (C & F). Fringe displacements in D–F are given in arbitrary units.

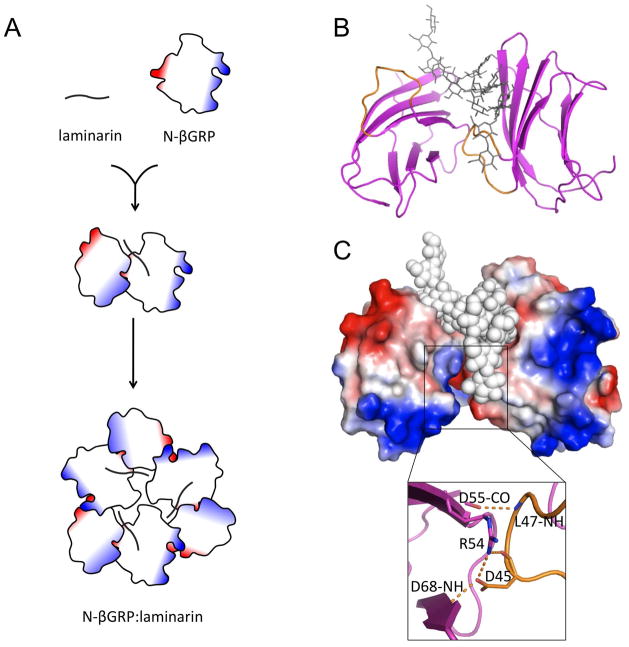

Figure 7.

A schematic representation of formation of N-βGRP: β-1,3-glucan macro complex: (A) Laminarin binding to N-βGRP and self-association of N-βGRP:laminarin complex; (B) & (C) N-βGRP packing and concomitant electrostatic interactions as can be observed in the crystal structure of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose (12). Negative and positive potential surfaces are shown in red and blue, respectively.

Biological Implication of Self-association of N-βGRP:Laminarin Complex

Earlier work (9) has established that N-βGRP and laminarin produce a pronounced synergistic activation of the proPO pathway. Formation of a macro assembly of the protein:carbohydrate complex in solution, as characterized in the current work, likely allows for ready recruitment of circulating βGRP molecules in the hemolymph to initiate protease cascades that function in defense against invading pathogens. The nature of protein-protein interactions present in the complex may be gleaned from a pseudoquadruplex observed in the crystal structure of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose complex (12): In the unit cell N-βGRP molecules pack in a side-by-side fashion due to strong electrostatic attractions such that the tip of the loop connecting strands C and C′ of one molecule fits into a cleft formed between strands C′ and E of another molecule. This structural arrangement is stabilized predominantly by the hydrogen bonds and the salt bridge formed between Leu47 and Asp45 of one protein molecule and Asp55, Arg54, and Asp68 of another (Figure 7 B & C).

To test the hypothesis that these electrostatic interactions play a role in the formation of protein:carbohydrate macro complex, we selected Asp45 for mutagenesis because it makes a hydrogen bond with Asp68 and a salt bridge with Arg54 of another protein molecule through its side-chain carboxyl group (Figure 7C, inset). The sedimentation profiles of N-βGRP and mutants, D45A and D45K, reveal that the complex formed with D45K shifted to 4 S compared to the 5 S complex formed with the wild type protein. On the other hand, the protein:laminarin macro complex formed by the D45A mutant does not show any change relative to the wild type complex. These results indicate that in the D45K mutant, electrostatic repulsion between positively charged Lys45 and Arg54 on one hand, and absence of a hydrogen bond between Lys45 and Asp68 on the other, perturb the protein:carbohydrate macro complex formation. Clearly, other protein-protein and protein-carbohydrate interactions contribute significantly to the stability of the macro protein:carbohydrate complex, as the D45A mutant shows no alteration in its ability to interact with laminarin and make the protein:carbohydrate macro complex, as compared to the wild type protein. It is of interest to note that while Arg54 is conserved in the three-dimensional structures of N-βGRPs from P. interpunctella, B. mori, and D. melanogaster, Asp45 in P. interpunctella N-βGRP is replaced by a Glu in the other two species (Figure 1A).

β-1,3-glucan-binding activities of D45A and D45K mutants were compared with that of the wild-type protein by curdlan pull-down assay and ITC with laminarin (Supplementary Figure 2). Neither of these mutations has any effect on carbohydrate-binding activity. Thus, it is concluded that the electrostatic attractions involving Asp45 (Figure 7C), as deduced from the crystal structure of N-βGRP:laminarihexaose (12), contribute to the self-association of N- β GRP:laminarin complex.

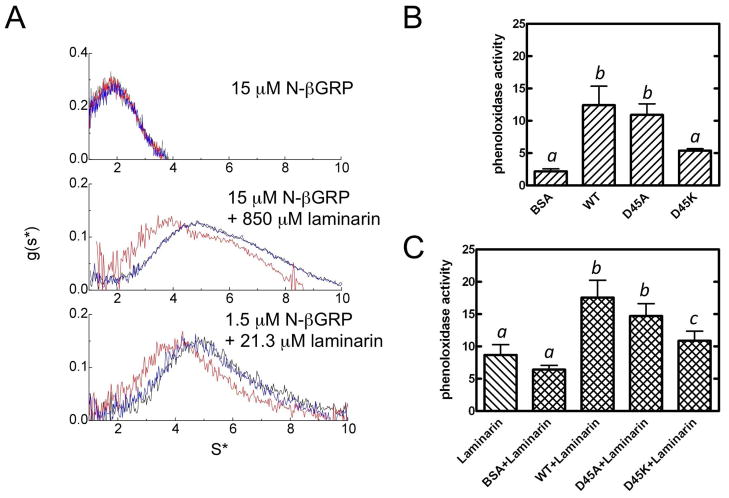

Functional significance of the protein:carbohydrate macro complex formation was characterized by measuring proPO activation in insect blood plasma by the wild-type and mutant N-βGRPs in the absence and presence of laminarin (Figure 8B & C). The D45K mutation decreased proPO activation both in the absence of, and, to a smaller extent, in the presence of, laminarin, while the D45A mutation showed no change, consistent with the AUC data (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Electrostatic interactions play a role in the formation of N-βGRP: β-1,3-glucan macro complex: (A) Sedimentation velocity profiles for N-βGRP (wide type, black; D45A, blue; and D45K, red) in the presence of laminarin; Activation of the prophenoloxidase pathway by N- βGRP and mutants without (B) or with laminarin (C). Samples of plasma (5 μl) were mixed with protein alone or with protein and laminarin. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, phenoloxidase activity was measured using dopamine hydrochloride as a substrate, as described under “Experimental Procedures”. The bars represent the means ± S.E. of data from three sets of measurements on a pooled plasma sample. Bars labeled with different letters (a, b, and c) are significantly different [analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05].

Formation of a macro structure of βGRP:β-1,3-glucan complex, a likely cooperative process, might present a repeating pattern and thus provide an effective platform to initiate innate immune responses (36,37). Such an arrangement is reminiscent of peptidoglycan recognition by insect peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) (38). It is also of interest to note that some lectins which have a low binding affinity for monosaccharides increase their affinities significantly for oligosaccharides by forming a cluster of lectin-oligosaccharide complexes (39).

The present study thus presents a three-dimensional solution structure of P. interpunctella N- βGRP that is highly similar to its crystal structure (12), provides supporting evidence for laminarihexaose-binding site, and presents data for a novel mechanism of proPO activation in insect immune response that involves self-association of the initial protein:carbohydrate complex, and finally demonstrates the biological relevance of this important step.

CONCLUSION

Biophysical characterization of interactions between laminarin, a β-1,3-glucan, and N-terminal domains of insect βGRPs in solution has led to the novel finding that a stable macro complex results from self-association of the initially formed N-βGRP:laminarin complex. Electrostatic interactions between bound protein molecules in the macro complex contribute to its stability and ability to influence the rate of activation of the prophenoloxidase pathway. An increase in β-1,6 branching of laminarin reduces the carbohydrate’s βGRP-binding affinity. Macro protein:carbohydrate complexes appear to provide an efficient means for recruiting immune response proteins and thus amplifying the initial response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported in part by a grant from the NIH (GM41247 to M. K.). This is contribution 12-352-J from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

We thank the Biotechnology Core Facility at Kansas State University for assistance in carrying out mass spectrometry experiments.

ABBREVIATIONS

- βGRP

β-1,3-glucan recognition protein

- GNBP

Gram-negative bacteria binding protein

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- ppm

parts per million

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- AUC

analytical ultracentrifugation

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- pproPO

prophenoloxidase

Footnotes

Atomic coordinates have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession number 2KHA.

The supporting information includes a table of statistics for a structural ensemble of 20 lowest- energy structures of Plodia interpunctella N-βGRP; MALDI mass spectrum of laminarin, figure of β-1,3-glucan-binding activities of N-βGRP and mutants as measured by curdlan pull-down assay and isothermal titration calorimetry, g(s*) profiles of sedimentation velocity studies of N-β GRP in the presence of varying amounts of laminarihexaose, and sedimentation velocity profiles of N-βGRP:laminarin complex with increasing amounts of laminarin. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ochiai M, Ashida M. A pattern-recognition protein for β-1,3-glucan. The binding domain and the cDNA cloning of β-1,3-glucan recognition protein from the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4995–5002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma C, Kanost MR. A β1,3-glucan recognition protein from an insect, Manduca sexta, agglutinates microorganisms and activates the phenoloxidase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7505–7514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Ryu JH, Han SJ, Choi KH, Nam KB, Jang IH, Lemaitre B, Brey PT, Lee WJ. Gram-negative bacteria-binding protein, a pattern recognition receptor for lipopolysaccharide and β-1,3-glucan that mediates the signaling for the induction of innate immune genes in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32721–32727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabrick JA, Baker JE, Kanost MR. cDNA cloning, purification, properties, and function of a β-1,3-glucan recognition protein from a pyralid moth, Plodia interpunctella. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:579–594. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang H, Ma C, Lu ZQ, Kanost MR. β-1,3-glucan recognition protein-2 (βGRP-2)from Manduca sexta; an acute-phase protein that binds β-1,3-glucan and lipoteichoic acid to aggregate fungi and bacteria and stimulate prophenoloxidase activation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottar M, Gobert V, Matskevich AA, Reichhart JM, Wang C, Butt TM, Belvin M, Hoffmann JA, Ferrandon D. Dual detection of fungal infections in Drosophila via recognition of glucans and sensing of virulence factors. Cell. 2006;127:1425–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An C, Ishibashi J, Ragan EJ, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Functions of Manduca sexta hemolymph proteinases HP6 and HP8 in two innate immune pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19716–19726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roh KB, Kim CH, Lee H, Kwon HM, Park JW, Ryu JH, Kurokawa K, Ha NC, Lee WJ, Lemaitre B, Söderhäll K, Lee BL. Proteolytic cascade for the activation of the insect toll pathway induced by the fungal cell wall component. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19474–19481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrick JA, Baker JE, Kanost MR. Innate immunity in a pyralid moth: functional evaluation of domains from a β-1,3-glucan recognition protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26605–26611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matskevich AA, Quintin J, Ferrandon D. The Drosophila PRR GNBP3 assembles effector complexes involved in antifungal defenses independently of its Toll-pathway activation function. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1244–1254. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahasi K, Ochiai M, Horiuchi M, Kumeta H, Ogura K, Ashida M, Inagaki F. Solution structure of the silkworm βGRP/GNBP3 N-terminal domain reveals the mechanism for β-1,3-glucan-specific recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11679–11684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901671106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanagawa M, Satoh T, Ikeda A, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Yamaguchi Y. Structural insights into recognition of triple-helical β-glucans by an insect fungal receptor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29158–29165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishima Y, Quintin J, Aimanianda V, Kellenberger C, Coste F, Clavaud C, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA, Latge JP, Ferrandon D, Roussel A. The N-terminal domain of Drosophila Gram-negative binding protein 3 (GNBP3) defines a novel family of fungal pattern recognition receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28687–28697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hrmova M, Fincher GB. Purification and properties of three (1–3)-β-D-glucanase isoenzymes from young leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare) Biochem J. 1993;289:453–461. doi: 10.1042/bj2890453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handa N, Nisizawa K. Structural investigation of a laminaran isolated from Eisenia bicyclis. Nature. 1961;192:1078–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY. Vol. 3. University of California; San Francisco, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavanagh C, Palmer AG, 3rd, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiromasa Y, Fujisawa F, Aso Y, Roche TE. Organization of the cores of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex formed by E2 and E2 plus the E3-binding protein and their capacities to bind the E1 and E3 components. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6921–6933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins SJ, Miller A, Hardingham TE, Muir H. Physical properties of the hyaluronate binding region of proteoglycan from pig laryngeal cartilage: Densitometric and small-angle neutron scattering studies of carbohydrates and carbohydrate-protein macromolecules. J Mol Biol. 1981;150:69–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laughton AM, Siva-Jothy MT. A standardised protocol for measuring phenoloxidase and prophenoloxidase in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Apidologie. 2011;42:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Multidimensional heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:349–363. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng JW, Wagner G. Investigation of protein motions via relaxation measurements. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:563–596. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amzel LM, Poljak RJ. Three-dimensional structure of immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:961–997. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.004525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuyama K, Otsubo A, Fukuzawa Y, Ozawa M, Harada T, Kasai N. Single helical structure of native curdlan and its aggregation state. Carbohydr Chem. 1991;10:645–656. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deslandes Y, Marchessault RH, Sarko A. Triple-helical structure of (1–3)-β-D-glucan. Macromolecules. 1980;13:1466–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barral P, Suarez C, Batanero E, Alfonso C, de Alche JD, Rodriguez-Garcia MI, Villalba M, Rivas G, Rodriguez R. An olive pollen protein with allergenic activity, Ole e 10, defines a novel family of carbohydrate-binding modules and is potentially implicated in pollen germination. Biochem J. 2005;390:77–84. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young SH, Dong WJ, Jacobs RR. Observation of a partially opened triple-helix conformation in 1->3-β-glucan by fluorescence resonance energy transfer spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11874–11879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schachman HK. Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry. Academic Press; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem J. 2004;382:769–781. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiromasa Y, Roche TE. Facilitated interaction between the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 2 and the dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33681–33693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Jiang H. Interaction of β-1,3-glucan with its recognition protein activates hemolymph proteinase 14, an initiation enzyme of the prophenoloxidase activation system in Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9271–9278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513797200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchon N, Poidevin M, Kwon HM, Guillou A, Sottas V, Lee BL, Lemaitre B. A single modular serine protease integrates signals from pattern-recognition receptors upstream of the Drosophila Toll pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12442–12447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901924106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim JH, Kim MS, Kim HE, Yano T, Oshima Y, Aggarwal K, Goldman WE, Silverman N, Kurata S, Oh BH. Structural basis for preferential recognition of diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan by a subset of peptidoglycan recognition proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8286–8295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weis WI, Drickamer K. Structural basis of lectin-carbohydrate recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.