Abstract

Mangafodipir is a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent with manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) mimetic activity. The MnSOD mimetic activity protects healthy cells against oxidative stress-induced detrimental effects, e.g., myelosuppressive effects of chemotherapy drugs. The contrast property depends on in vivo dissociation of Mn2+ from mangafodipir—about 80% dissociates after injection. The SOD mimetic activity, however, depends on the intact Mn complex. Complexed Mn2+ is readily excreted in the urine, whereas dissociated Mn2+ is excreted slowly via the biliary route. Mn is an essential but also a potentially neurotoxic metal. For more frequent therapeutic use, neurotoxicity due to Mn accumulation in the brain may represent a serious problem. Replacement of 4/5 of Mn2+ in mangafodipir with Ca2+ (resulting in calmangafodipir) stabilizes it from releasing Mn2+ after administration, which roughly doubles renal excretion of Mn. A considerable part of Mn2+ release from mangafodipir is governed by the presence of a limited amount of plasma zinc (Zn2+). Zn2+ has roughly 103 and 109 times higher affinity than Mn2+ and Ca2+, respectively, for fodipir. Replacement of 80% of Mn2+ with Ca2+ is enough for binding a considerable amount of the readily available plasma Zn2+, resulting in considerably less Mn2+ release and retention in the brain and other organs. At equivalent Mn2+ doses, calmangafodipir was significantly more efficacious than mangafodipir to protect BALB/c mice against myelosuppressive effects of the chemotherapy drug oxaliplatin. Calmangafodipir did not interfere negatively with the antitumor activity of oxaliplatin in CT26 tumor-bearing syngenic BALB/c mice, contrary calmangafodipir increased the antitumor activity.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are known to participate in pathological tissue damage, for instance, during treatment with chemotherapy drugs in cancer patients [1]. The mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) plays a key role in the cellular defense against reactive oxygen-derived free radicals by dismutating superoxide anions (·O2-), which normally leak from the respiratory chain during mitochondrial reduction of O2 to H2O at fairly high amounts. Super-oxide is also produced by nicotinamide adenine denucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. Under normal circumstances, it represents an important mechanism by which neutrophils (NEU) kill invading bacteria and fungi. However, ·O2- is involved in many pathological conditions, e.g., myocardial ischemia-reperfusion damage, doxorubicin myocardial toxicity, atherosclerosis, and paracetamol hepatotoxicity.

Yet as recently as 45 years ago, oxygen-derived radicals were not thought to occur in living cells. Radicals were thought to be so reactive and unselective that they could not occur in biologic systems. That view changed dramatically in 1967 when Irwin Fridovich and Joe McCord discovered the antioxidant enzyme SOD, a discovery that without doubts belongs to one of the most important biologic discoveries during the last century. Mitochondrial MnSOD catalyzes dismutation of ·O2- at an extremely high rate (>109 M-1s-1). The reaction rate is actually close to the diffusion limit of ·O2- [2], which indicates the immense importance of MnSOD in the cellular defense against oxidative stress. During pathological oxidative stress, the production of ·O2- exceeds the endogenous protective potential. Moreover, ·O2- reacts readily with nitric oxide (NO·) to form highly toxic peroxynitrite (ONOO-), which nitrates tyrosine residues of the MnSOD enzyme and irreversibly inactivates the enzyme. Many years ago, this mechanism was suggested to participate in chronic rejection of human renal allografts [3] and recent results indicate nitration of MnSOD to be an early step in paracetamol (acetaminophen)-induced liver failure [4].

The balance between the mitochondrial antioxidant detoxification system and ROS is finely maintained and low levels of mitochondrial ROS are required by cells to modulate normal redox biology [5]. Excessive amounts of ROS, however, are believed to shorten life span and to induce age-associated pathological conditions, such as carcinogenesis, cardiovascular, and other diseases [6].

Although inflammatory processes secondary to oxidative stress damage normal tissue, they may be beneficial to tumor tissue by creating growth factor-rich microenvironment and giving the cancerous clones the need to start growing [7,8]. A body of evidence suggests that whether MnSOD protects normal tissue it may paradoxically make tumor tissue much more sensitive to radiation-induced [9,10] and chemotherapy-induced [11] damaging effects.

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent manganese dipyridoxyl diphosphate (mangafodipir; MnDPDP) was approved in 1997 for use as a diagnostic MRI contrast agent in humans. Importantly, mangafodipir has also been shown to protect mice against serious side effects of several chemotherapy drugs (doxorubicin, oxaliplatin, and paclitaxel), without interfering negatively with the anticancer effects of these drugs [12–15]. This includes protection against serious reduction in leukocytes [14]. Mangafodipir (i.e., the ready-to-use MRI contrast agent Teslascan) has been tested in one colon cancer patient going through palliative treatment with a combination of folinate, 5-fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin [16], and a first clinical feasibility study in colon cancer patients going through adjuvant 5-fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) showing promising results was recently published [17]. Mangafodipir has also been described to protect mice against acetaminophen-induced liver failure [18,19].

Mn is an essential as well as potentially neurotoxic metal. It has been known for many years that under conditions of chronic exposure to high levels of Mn, a syndrome of extrapyramidal dysfunction similar to Parkinson syndrome frequently occurs, although clinically a different disease entity [20]. When a diagnostic MRI dose of mangafodipir is intravenously (i.v.) injected into humans, more than 80% of the administered Mn is released [21,22]. Release of paramagnetic Mn2+ is in fact a prerequisite for the diagnostic MRI properties of mangafodipir [22,23]. However, the therapeutic effects of mangafodipir depend on the intact Mn complex [24,25] because Mn undergoes redox cycling (Mn2+/Mn3+) during the catalytic superoxide dismutating cycle [2].

A considerable part of the release of Mn2+ from fodipir (DPDP) is governed by the presence of a limited amount of free or loosely bound zinc (Zn2+) in the plasma [21]. Zn2+ has roughly 1000 times higher affinity than Mn2+ for fodipir [26], and replacement of Mn2+ with more loosely bound Ca2+ may hence reduce the amount of Mn2+ released after injection. Ca2+ has approximately 106 times lower affinity than Mn2+ for fodipir [27].

The present paper describes how replacement of about 4/5 of the Mn2+ within mangafodipir with Ca2+ considerably stabilizes it from releasing potentially neurotoxic Mn and simultaneously increases the therapeutic efficacy significantly.

Materials and Methods

Test Substances

Calmangafodipir [Ca4Mn(DPDP)5; Lot No. 11AK0105B; 98.8% pure], mangafodipir (MnDPDP; Lot No.02090106; >99.9% pure), fodipir (DPDP; Lot No. RDL02090206), and PLED [Lot No. KER-AO-122(2)] were exclusively synthesized for PledPharma by Albany Molecular Research, Inc (Albany, NY). The metabolites MnPLED, ZnDPDP, and ZnPLED were gifts from GE Healthcare (Oslo, Norway). Calfodipir (CaDPDP) was prepared by adding equimolar amount of CaCl2 to a stock solution of fodipir (DPDP). Ready-to-use Teslascan (10 mM containing 6 mM ascorbic acid) was from GE Healthcare. Before injection, the test substances were dissolved in 0.9% NaCl solution to suitable strengths.

Oxaliplatin used in the myelosuppressive studies was from Sanofiaventis (Eloxatin, 5 mg/ml), and that used in the tumor studies was from Teva (Hälsingborg, Sweden). Before injection, oxaliplatin was diluted in 5% glucose to a suitable strength.

Animals

Male Wistar rats (approximately 250 g) used in the excretion studies were from Taconic (Ry, Denmark), whereas male and female rats used in the studies on Mn distributions in the brain and other selected organs after repeated administration were from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). BALB/c female mice (6–8 weeks) used in the myelosuppressive studies were from Charles River, and BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) used in the tumor studies were from Taconic. The animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committees on animal research.

Renal Excretion of Mn and Zn in Rats

In a first series of experiments, 10 male Wistar rats (approximately 250 g) were injected i.v., via one of the tail veins, with either 0, 0.125, 0.250, 0.500, or 0.750 ml of a 10 mM fodipir (DPDP) solution, corresponding to 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 µmol/kg.

In the second series of experiments, eight male Wistar rats (approximately 250 g) were injected i.v., via one of the tail veins, with 0.25 ml of a 50 mM calmangafodipir solution, containing 10 mM Mn2+ and 40 mM Ca2+, or 0.25 ml of 10 mM mangafodipir, containing 10 mM Mn2+, corresponding to an Mn2+ dose of 10 µmol/kg in both cases. To obtain basal levels of Mn and Zn in urine, two additional (control) rats received 0.25 ml of saline and were placed in metabolic cages for urine collection over the same period of time.

After injection, the rats were immediately placed in metabolic cages for urine collection over a period of up to 24 hours. The urine samples were then stored at -80°C until Mn and Zn analysis. Before analysis, the samples were thawed and extensively shaken to obtain homogenous samples. A 5 ml of aliquot was taken from each sample and 5 ml concentrated nitric acid was added. The samples were then resolved in a microwave oven and thereafter diluted with distilled water to a final volume of 50 ml. The Mn and Zn contents of each sample were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Identical samples of calmangafodipir and mangafodipir as those injected in the rats (i.e., 0.250 ml) were withdrawn and injected into test tubes. These samples were treated in an identical manner to that of the urine samples and analyzed for its Mn content.

Organ Retention of Mn after Repeated Administration of Calmangafodipir or Mangafodipir in Rats

Wistar male and female rats were i.v. injected with either 0.9% NaCl, 72.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir (corresponding to 72.0 µmol/kg Mn), or 374.4 µmol/kg calmangafodipir (corresponding to 72.0 µmol/kg Mn) three times a week for 13 weeks (each treatment group consisted of nine males and nine females). Each dose of calmangafodipir corresponded to about 36 times the assumed clinical dose. After the 13-week administration period, the rats were killed and the brains and pancreas were dissected out and approximately 0.5 g of samples were stored frozen until Mn analysis. The Mn content of each sample was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.

In Vivo Myeloprotective Effects of Calmangafodipir, Mangafodipir, Teslascan, and MnPLED against Oxaliplatin in BALB/c Mice

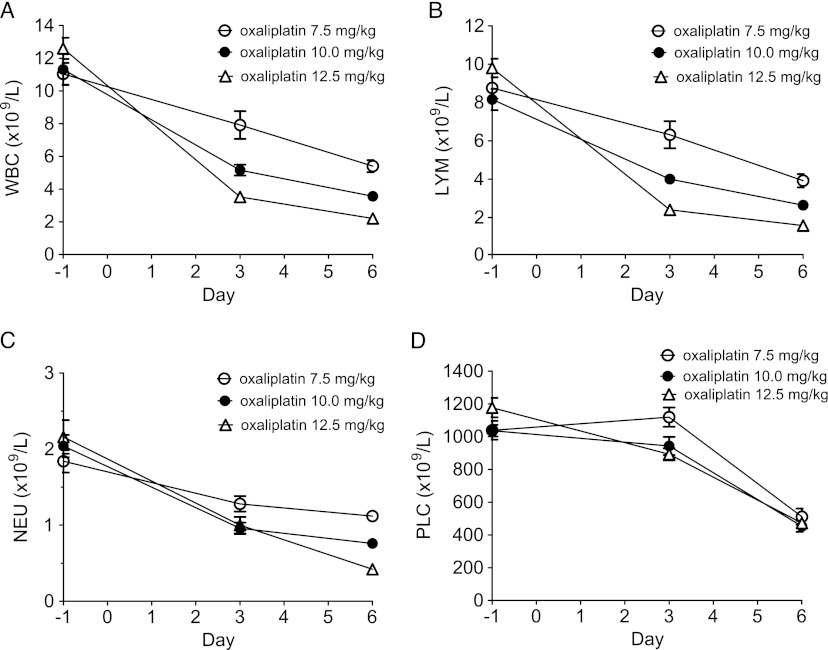

In a first series of experiments, three groups each consisting of five female BALB/c mice were treated once intraperitoneally (i.p.) with oxaliplatin at 7.5, 10.0, and 12.5 mg/kg oxaliplatin, respectively. One day before (baseline) as well as 3 and 6 days after oxaliplatin treatment, 50 µl of EDTA blood samples was taken from the orbital venous plexus with a glass capillary. The blood samples were analyzed using the automated system CELL-DYN Emerald (Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesenbaden, Germany) for the content of white blood cells (WBC), lymphocytes (LYM), NEU, and platelets (PLC). CELL-DYN Emerald is accredited for human blood samples. The used device is, however, especially calibrated for mouse blood samples. The CELL-DYN Emerald mouse data obtained at the present laboratory have repeatedly been compared with data from an accredited external laboratory (device: XT2000I; Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany). These comparisons have always resulted in strong correlations regarding WBC, LYM, and NEU (data not shown).

From the results (Figure 1), it was concluded that further experiments testing the myeloprotective effects of calmangafodipir, mangafodipir, Teslascan, and MnPLED should be performed at 12.5 mg/kg oxaliplatin and that blood cell sample analyses should be performed the day before and 6 days after oxaliplatin administration in every mouse. Thirty minutes before and 24 hours after oxaliplatin administration, mice received saline, calmangafodipir [6.5 µmol/kg; Ca4Mn(DPDP)5], mangafodipir (1.3 and 13.0 µmol/kg), Teslascan (13.0 µmol/kg), or MnPLED (2.0 µmol/kg) i.v. (five mice in each group). A control group received vehicle (5% glucose) instead of oxaliplatin and saline instead of test substance.

Figure 1.

The myelosuppressive effects of increasing single doses (7.5, 10.0, and 12.5 mg/kg) of oxaliplatin on (A) WBC, (B) LYM, (C) NEU, and (D) PLC at 3 and 6 days after injection. Results expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 in each group).

An additional group of five animals received 6.5 µmol/kg (5 mg/kg) calmangafodipir with a treatment schedule identical to the above described experiments (calmangafodipir 30 minutes before and 24 hours after 12.5 mg/kg oxaliplatin; “double dose”). Another group of five mice received just one calmangafodipir treatment, 6.5 µmol/kg, 30 minutes before oxaliplatin (“single dose”). Two further groups of mice receiving either vehicle (i.e., saline plus glucose) or oxaliplatin (i.e., saline plus oxaliplatin) treatment were run in parallel.

The In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of Calmangafodipir, Mangafodipir, Fodipir, and Metabolites in CT26 Cells

The viability of cells was measured using the methylthiazoletetrazolium assay. Briefly, 8000 CT26 (mouse colon carcinoma) cells were seeded per well on a 96-well plate and grown overnight in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 UI/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

In a first series of experiments, cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of oxaliplatin (0.1–100 µM) for 48 hours at 37°C, in the absence and presence of various concentrations of fodipir (10, 30, and 100 µM).

In a second series of experiments, cells were then exposed for 48 hours to 1 to 1000 µM calmangafodipir, fodipir, PLED, calfodipir, mangafodipir, MnPLED, ZnPLED, ZnDPMP, and CaCl2 at 37°C.

The viability of the cells was then assessed by adding 5 mg/ml methylthiazoletetrazolium to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubating cells for a further 4 hours at 37°C. The blue formazan that is formed by mitochondrial dehydrogenases of viable cells was then dissolved overnight at 37°C by adding 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 10 mM HCl to a final concentration of 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 5 mM HCl. Finally, the absorbance of the solution was read at 570 nm with a reference at 670 nm in a microplate reader Spectramax 340 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) connected to an Apple Macintosh computer running the program Softmax Pro V1.2.0 (Molecular Devices).

Antitumor Effects of Oxaliplatin in CT26 Tumor-Bearing Syngenic Mice in the Absence and Presence of Calmangafodipir

CT26 cells were grown in 75-cm2 culture flasks in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 UI/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. When the cells reached ∼50% confluency, they were harvested by trypsinization. Briefly, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3) and exposed to 0.05% trypsin/0.53 mM EDTA at 37°C for ∼5 minutes. The trypsinization was stopped by adding RPMI 1640 culture medium. Cells were counted and centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes. Thereafter, they were washed in PBS, centrifuged again, and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 2 x 106/350 µl for injection into mice. Briefly, each mouse was injected subcutaneously in the back of the neck with 2 x 106 of CT26 cells at day 0. After 7 days (day 7) when the tumors were detectable, the tumor size was determined with a caliper and mice were grouped (five in each) so that the sizes of the tumors were not statistically different by group. Oxaliplatin ± calmangafodipir were injected and one group of mice received vehicle (0.9% saline + 5% glucose) treatment alone.

In a first series of experiments, mice were injected i.v. with saline or 50 mg/kg (65 µmol/kg) calmangafodipir 30 minutes before i.p. administration of 20 mg/kg oxaliplatin (diluted in 5% glucose) or 5% glucose. These mice received in addition saline or 65.0 µmol/kg (50 mg/kg) calmangafodipir 24 hours later (day 8). In another series of experiments, mice were injected i.v. with saline or 6.5 µmol/kg (5 mg/kg) or 32.5 µmol/kg (25 mg/kg) calmangafodipir 30 minutes before i.p. administration of 10 mg/kg oxaliplatin (diluted in 5% glucose) or 5% glucose, and saline or 6.5 µmol/kg or 32.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir 24 hours later (day 8). The mice were killed on day 10 and the tumors were excised, and wet weights (w.w.s) were determined.

Calculations, Presentation of Results, and Statistics

Renal excretion of Mn and Zn are presented as total 0- to 24-hour urine content (expressed as µmol/kg ± SEM) and as percentage (±SEM) of the injected dose. The organ content of Mn is expressed as µg/g w.w. (±SEM). The myelosuppressive effects of oxaliplatin alone and in the presence of calmangafodipir, mangafodipir, Teslascan, or MnPLED are presented in graphs as relative changes from baseline (day -1) for the blood cells (±SEM). The viability of CT26 cells in the presence of an increasing concentration of the various test substances is presented as concentration-response curves (mean ± SD). Where appropriate, the individual curves were fitted to the sigmoidal normalized response logistic equation (Graphpad Prism, version 5.02, La Jolla, CA). From this analysis, the pD2 (negative log of the concentration of a drug that produces half its maximal response, -log EC50) values of the test substances were calculated; pD2 values are presented together with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical differences between the other treatments, where appropriate, were tested by Student's t test. P values lower than .05 were considered as statistically significant differences.

Results

Renal Excretion of Mn and Zn after i.v. Administration of Fodipir, Mangafodipir, and Calmangafodipir

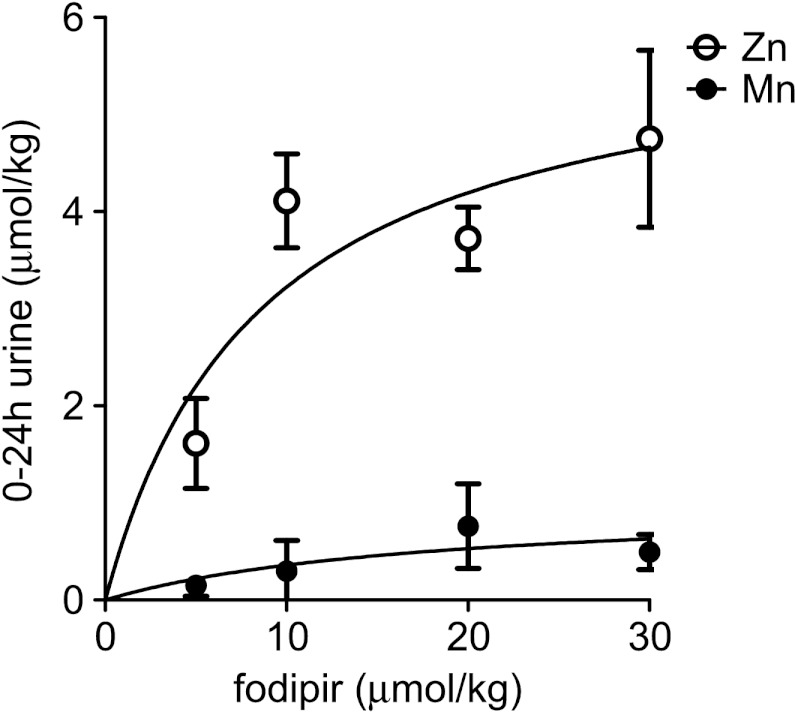

Results from the first series of excretion experiments are shown in Figure 2 (after subtracting basal Zn and Mn excretion). The basal 0- to 24-hour excretion of Zn in two control rats was found to be 0.852 and 0.771 µmol/kg body weight (b.w.), respectively. The 0- to 24-hour Zn excretion more or less saturated around 4 µmol/kg Zn at a dose of 10 µmol/kg fodipir. Fodipir had just minor effects on the Mn excretion. As evident from this figure, fodipir is capable of increasing Zn excretion considerably.

Figure 2.

Zero- to twenty-four-hour Zn and Mn renal excretion in rats at increasing doses of fodipir (mean ± SEM; n = 10).

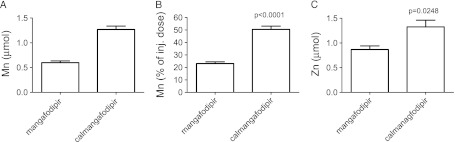

Results from the second series of experiments are shown in Figure 3. Twenty-four hours after i.v. injection of 0.25 ml of 10 mM mangafodipir containing 2.59 µmol Mn, 0.60 ± 0.04 µmol Mn was recovered in urine (Figure 3A), corresponding to 23.1 ± 1.4% of the injected dose (Figure 3B). The corresponding figure after injection of 0.25 ml of 50 mM calmangafodipir containing 2.52 µmol Mn was 1.27 ± 0.07 µmol Mn (Figure 3A), corresponding to 50.5 ± 2.6% of the injected dose (Figure 3B). The difference between mangafodipir and calmangafodipir was highly significant (P < .0001). The difference in renal Mn excretion was more or less reflected in the difference in renal excretion of Zn, expressed as increased Zn excretion, i.e., after the basal 24-hour excretion values (0.068 µmol) was subtracted (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Increase in Mn content in 0- to 24-hour urine from rats injected with mangafodipir or calmangafodipir containing 2.59 µmol and 2.52 µmol Mn, respectively, expressed as (A) the total content of Mn (minus the basal content of Mn) and (B) the percentage of the injected dose. (C) The increase in Zn content in 0- to 24-hour urine in the same animals. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 in each group).

The present results demonstrate how replacement of about 4/5 of the Mn2+ in mangafodipir with Ca2+, resulting in calmangafodipir, stabilizes it from releasing Mn2+ after i.v. administration, which in turn roughly doubles the amount of Mn2+ excreted in the urine.

Organ Retention of Mn after Repeated Administration of Calmangafodipir or Mangafodipir

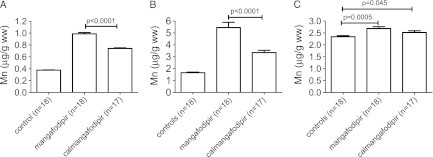

Results are shown in Figure 4. The Mn brain contents in NaCl-treated control, mangafodipir-treated, and calmangafodipir-treated rats were 0.38 ± 0.01, 0.99 ± 0.02, and 0.74 ± 0.01 µg/g w.w., respectively (Figure 4A), whereas the corresponding Mn contents in the pancreas were 1.66 ± 0.06, 5.54 ± 0.45, and 3.35 ± 0.19 µmol/kg, respectively (Figure 4B). The levels in control animals were more or less identical to those previously reported in rats by Ni et al. [28]. They reported that the brain and pancreas in control animals contained 6.7 and 26.7 nmol/g w.w., corresponding to 0.37 and 1.5 µg/g w.w., respectively. Although the Mn content of the liver was statistically significantly elevated in the mangafodipir group (Figure 4C), the relative elevation was much less than those seen in the brain and pancreas. A single diagnostic dose of mangafodipir (5 µmol/kg b.w.) is known to cause rapid increase in the Mn content of both the pancreas and the liver of rats—after 2 hours, the Mn content of the pancreas was approximately 10 times higher than the basal value, and the corresponding value of liver was increased about 2 times [28]. Whereas Ni et al. [28] found the Mn content still elevated after 24 hours in the pancreas (about five times the basal value), it was back to baseline in the liver at that time point. This presumably reflects the high capacity of the liver to handle Mn and its important physiological role in Mn homeostasis. This is further supported by the present results showing just a modest increase in liver Mn after heavy exposure to mangafodipir.

Figure 4.

Mn content of the (A) brain, (B) pancreas, and (C) liver, respectively, after 39 doses of either NaCl (controls), mangafodipir, or calmangafodipir (corresponding in both cases to an accumulated dose of 2800 µmol/kg Mn). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 17–18 in each group).

As obvious from Figure 4, A and B, calmangafodipir resulted in significantly less retention of Mn compared to mangafodipir, after repeated dosing in rats. The total dose in both cases corresponded to approximately 2800 µmol/kg of Mn (39 x 72 µmol/kg). These results demonstrate the improved toxicological profile of calmangafodipir in comparison to that of mangafodipir.

In Vivo Myeloprotective Effects of Calmangafodipir, Mangafodipir, Teslascan, and MnPLED against Oxaliplatin

A clear dose-response relationship between increasing doses of oxaliplatin and myelosuppression was evident (Figure 1). As stated in Materials and Methods section, it was concluded that further experiments testing the myeloprotective effects of calmangafodipir, mangafodipir, Teslascan, and MnPLED should be performed at 12.5 mg/kg oxaliplatin and that blood cell sample analyses should be performed the day before and 6 days after oxaliplatin or vehicle administration in every mice.

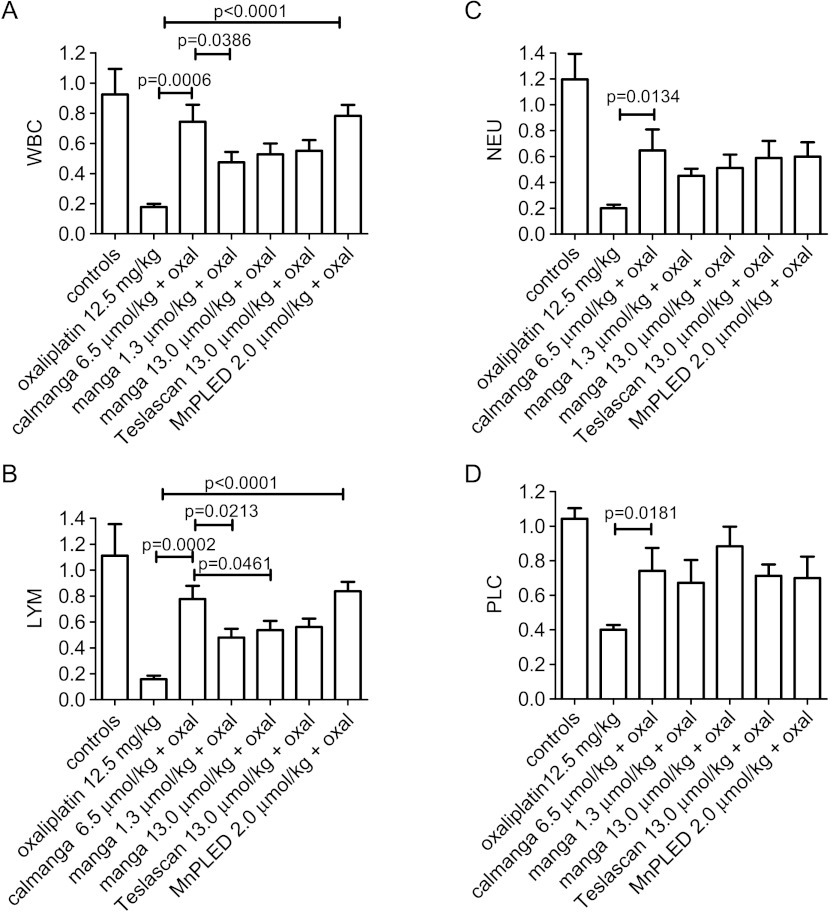

The absolute pre-values (day -1) and post-values (day 6) of WBC, LYM, NEU, and PLC are given in Table 1. The results, presented as relative differences in cell counts between day -1 and day 6 in each treatment group, are shown in Figure 5. At an equivalent Mn2+ dose, i.e., 6.5 µmol/kg (5 mg/kg), calmangafodipir [Ca4Mn(DPDP)5] was statistically significantly more efficacious than 1.3 µmol/kg (1 mg/kg) mangafodipir (MnDPDP) to protect the mice from oxaliplatin-induced fall in total number of WBC (Figure 5A). A single dose of 12.5 mg/kg oxaliplatin caused the WBC to fall more than 80%, whereas the fall in animals treated with calmangafodipir was only about 25%. The corresponding fall in mice treated with 1.3 or 13.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir was around 50%. Teslascan (13.0 µmol/kg, containing approximately 8 µmol/kg ascorbic acid) gave almost identical results as those of 13.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir, suggesting that ascorbic acid at this particular dose does not influence the protective activity of mangafodipir. Furthermore, the present results presumably also suggest that mangafodipir has to be dephosphorylated into MnPLED before it can exert myeloprotective effects—2 µmol/kg MnPLED was, like calmangafodipir, significantly more efficacious than 1.3 and 13.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir to protect WBC. Similar falls were seen in LYM (Figure 5B) and in NEU (Figure 5C) after oxaliplatin treatment, and the test substances gave qualitatively similar protection. Regarding PLC, in comparison to WBC, LYM, and NEU, they differed both in the sensitivity toward oxaliplatin (Figure 1D) and in the cytoprotective effects of the test substances (Figure 5D).

Table 1.

Myelosuppressive Effects of a Single Dose of 12.5 mg/kg Oxaliplatin in Untreated BALB/c Mice and in BALB/c Treated with Calmangafodipir [Ca4Mn(DPDP)5], Mangafodipir (MnDPDP), Teslascan, or MnPLED (Absolute Counts; Mean ± SEM; n = 5).

| WBC (109/l) | LYM (109/l) | NEU (109/l) | PLC (109/l) | |||||

| Day -1 | Day 6 | Day -1 | Day 6 | Day -1 | Day 6 | Day -1 | Day 6 | |

| Saline; oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/g) | 12.6 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1177 ± 59 | 473 ± 16 |

| Ca4Mn(DPDP)5 (6.5 µmol/kg); oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/kg) | 10.2 ± 0.8 | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1038 ± 29 | 773 ± 143 |

| MnDPDP (1.3 µmol/kg); oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/kg) | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 957 ± 21 | 638 ± 117 |

| MnDPDP (13.0 µmol/kg); oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/kg) | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 908 ± 18 | 800 ± 100 |

| Teslascan (13.0 µmol/kg); oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/kg) | 11.3 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 972 ± 7 | 693 ± 64 |

| MnPLED (2.0 µmol/kg); oxaliplatin (12.5 mg/kg) | 10.1 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1093 ± 49 | 857 ± 104 |

Figure 5.

Myeloprotective effects of calmangafodipir, mangafodipir, Teslascan, and MnPLED with regard to (A) WBC, (B) LYM, (C) NEU, and (D) PLC after oxaliplatin treatment in BALB/c mice. The results are presented as relative differences in cell counts between day -1 and day 6 in each treatment group. Controls received vehicle treatment only. Results expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 in each group).

In the above-described studies, the test substances were administered 30 minutes before oxaliplatin and 24 hours after (“double dose”). However, additional experiments comparing the myeloprotective effect of 6.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir given either as double dose (30 minutes before oxaliplatin and 24 hours after) or as a single dose (30 minutes before oxaliplatin) did not reveal any difference in myeloprotective efficacy (data not shown).

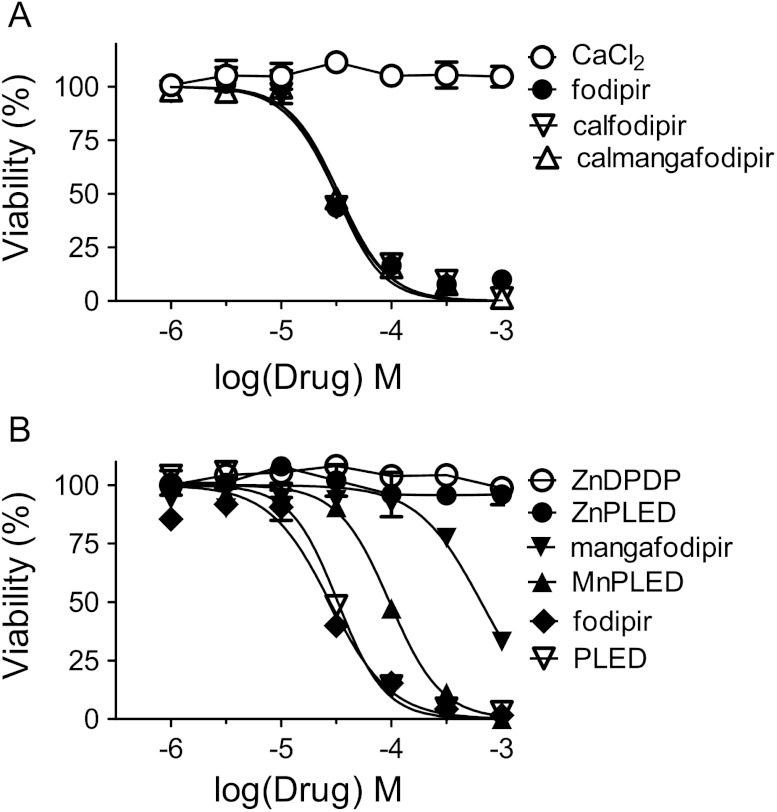

Cytotoxic Activity of Calmangafodipir, Mangafodipir, Fodipir, Calfodipir, and Metabolites in CT26 Cells

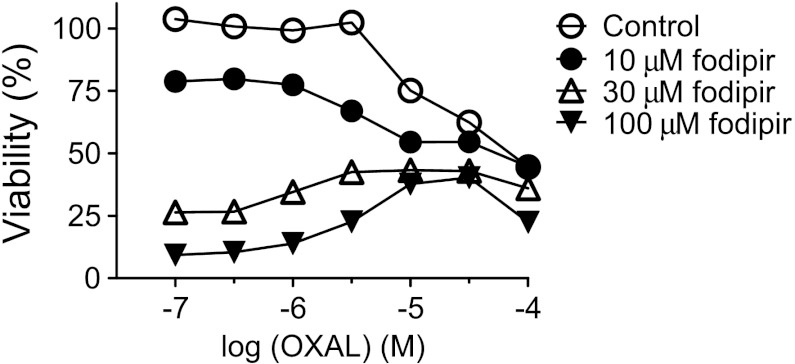

Oxaliplatin killed the CT26 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6). Neither 10, 30, nor 100 µM fodipir interfered negatively with the cancer cell killing ability of oxaliplatin. An additive effect of 10 µM fodipir was seen in the lower concentration range of oxaliplatin.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxic effects of oxaliplatin in the absence and presence of various concentrations of DPDP (mean ± SD; n = 3).

When comparing the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ratio between calmangafodipir and mangafodipir, the cytotoxic activity of fodipir, PLED, calfodipir, or calmangafodipir was about 20 times higher than that of mangafodipir (Figure 7, A and B; Table 2). MnPLED was six times more potent than mangafodipir (MnDPDP) in its ability to kill CT26 cancer cells. Neither ZnDPDP, ZnPLED, nor CaCl2 displayed any cytotoxic activity. Dissociation of Mn2+ from DPDP probably explains, to some extent, the cancer killing efficacy of mangafodipir. Calmangafodipir is, however, almost as efficacious as fodipir/calfodipir alone, i.e., the killing efficacy of calmangafodipir is much higher than that of mangafodipir.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic effects of increasing concentrations of (A) CaCl2, fodipir, calfodipir, and calmangafodipir and (B) ZnDPDP, ZnPLED, mangafodipir, MnPLED, fodipir, and PLED in CT26 cells (mean ± SD; n = 3).

Table 2.

IC50, Relative Efficacy (Compared to Fodipir), and pD2 Values of the Test Compounds.

| Compound | IC50 (M) | Relative Efficacy IC50 (Fodipir)/IC50 (x*) | pD2 (95% Confident Limit)† |

| Fodipir | 3.123 x 10-5 | 1.0 | 4.505 (4.432–4.579) |

| PLED | 3.269 x 10-5 | 1.0 | 4.486 (4.439–4.532) |

| Calmangafodipir | 3.351 x 10-5 | 0.9 | 4.475 (4.421–4.529) |

| Calfodipir | 3.153 x 10-5 | 1.0 | 4.501 (4.436–4.567) |

| Mangafodipir | 6.503 x 10-4 | 0.05 | 3.187 (3.103–3.271) |

| MnPLED | 9.628 x 10-5 | 0.3 | 4.016 (3.984–4.048) |

Test compound in question.

pD2 = -log(IC50).

The results suggest two important properties. First, PLED is probably as efficacious as its phosphorylated counterpart fodipir (DPDP) with respect to its cancer cell killing ability, and second, the lower in vitro stability of MnPLED in comparison to that of MnDPDP [26] probably explains the higher efficacy of MnPLED. The lack of any cytotoxic activity of ZnDPDP and ZnPLED is due to the 1000 times higher stability of these complexes in comparison to their Mn2+ counterparts [26].

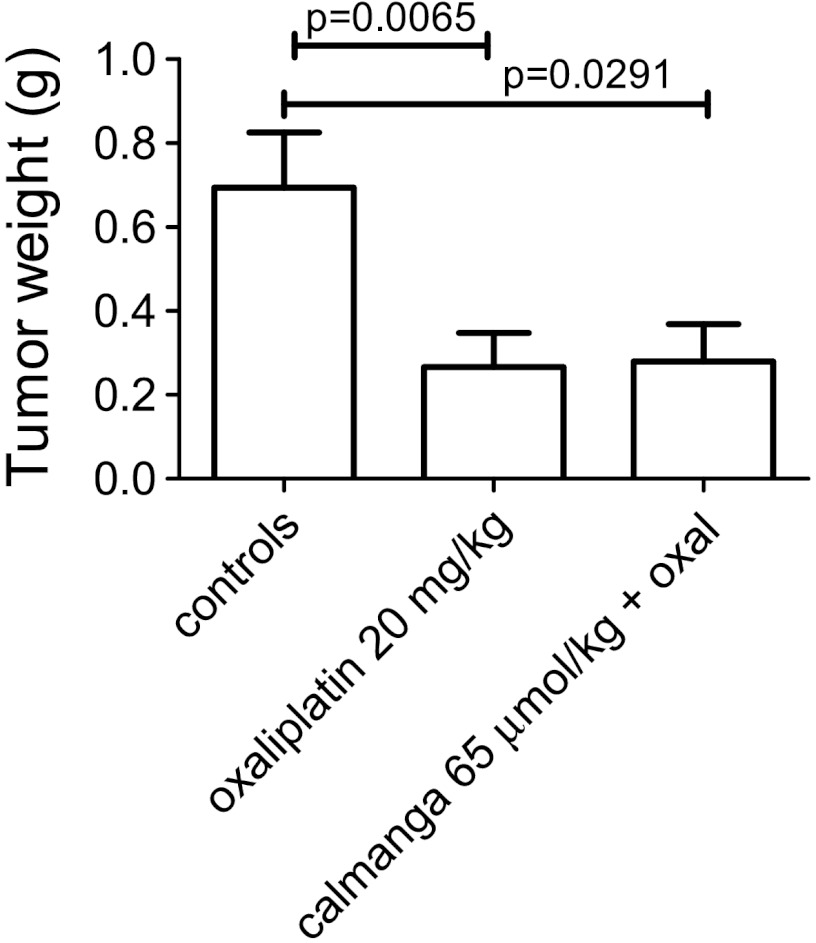

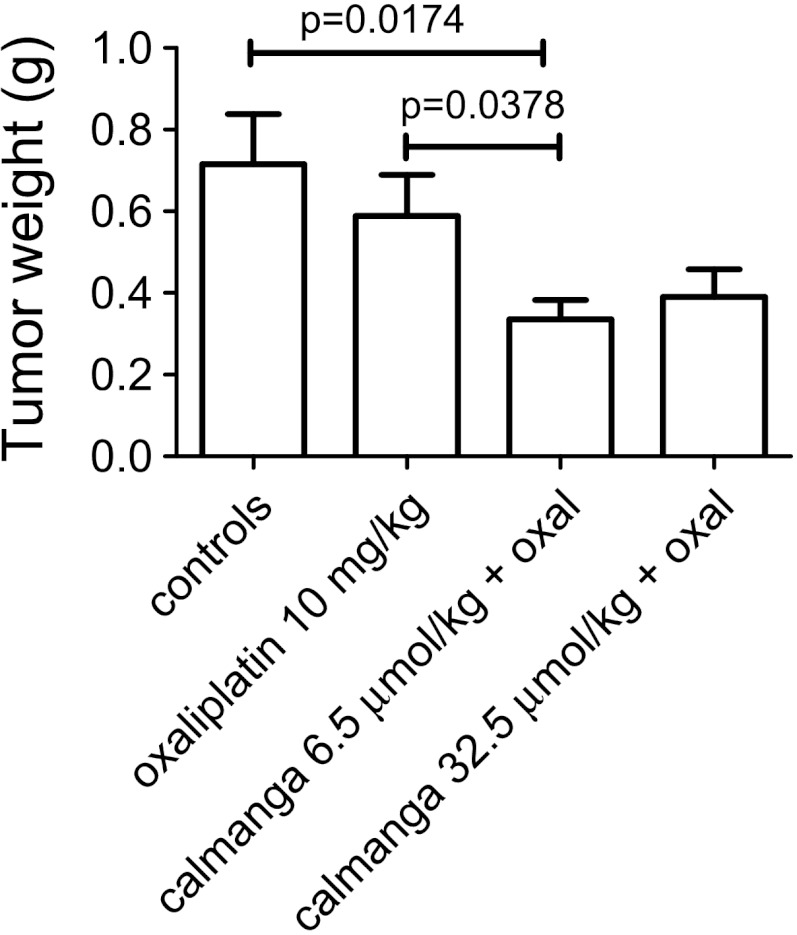

Antitumor Effects of Oxaliplatin in CT26 Tumor-Bearing Syngenic Mice in the Absence and Presence of Calmangafodipir

In the works on CT26 tumors by Laurent et al. and Alexandre et al. [12,14] conducted in France, they used a model where they allowed the tumor to grow to a size exceeding 10 cm3. However, to ensure accordance with the European Animal Welfare Guideline 2010/63/EU Article 15 and published guidelines, subcutaneous tumors in mice should not exceed 10% of the animal's own b.w. Therefore, similar to recommendations of Workman et al., studies presented here were finished when tumor volumes exceeded 1.2 cm3 [29]. Since the CT26 is a fast growing tumor cell line, we had to stop the study 10 days after inoculation of CT26 cells because several of the tumors at that time had reached a size of 1 cm3. Such a restriction of course makes it more difficult to study treatment-related effects on tumor growth. Nevertheless, we have been able to show a significant difference between oxaliplatin and non-oxaliplatin-treated CT26 tumor-bearing syngenic BALB/c mice.

The results are shown in Figures 8 and 9. In the first series of experiments, the mice received 20 mg/kg oxaliplatin, which is close to the highest tolerated dose. Single treatment with oxaliplatin resulted in a statistically significant and more than 50% reduction in tumor weight. Treatment with calmangafodipir (65.0 µmol/kg) did not have any negative impact on the antitumor effect of oxaliplatin at a high dose (Figure 8). However, in a second series of experiments in which 10 mg/kg oxaliplatin was used, treatment with a relatively low dose of calmangafodipir (6.5 µmol/kg) resulted in a statistically significant better antitumor effect (Figure 9); the combined effect of 10 mg/kg oxaliplatin plus 6.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir was almost as efficacious as 20 mg/kg oxaliplatin alone. Similar effects were seen after treatment with 32.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir.

Figure 8.

Antitumor effect of a high dose of oxaliplatin (20 mg/kg) in CT26 tumor-bearing syngenic BALB/c mice in the absence and presence of a relatively high dose of calmangafodipir (65.0 µmol/kg). Results expressed as mean ± SEM [n = 10 in vehicle and oxaliplatin (20 mg/kg) groups; n = 5 in the calmangafodipir group].

Figure 9.

Antitumor effect of a low dose of oxaliplatin (10 mg/kg) in the absence and presence of 6.5 and 32.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Discussion

When a relevant diagnostic imaging dose of mangafodipir, i.e., 5 to 10 µmol/kg, is injected into humans [21,22], or as in the present study into rats, about 80% of the administered Mn2+ is released. For diagnostic imaging purpose and for occasional therapeutic use, dissociation of Mn2+ from mangafodipir represents no major toxicological problem. However, for more frequent use, as in therapeutic use, accumulated Mn toxicity may represent a problem, particularly when it comes to neurotoxicity [20,30]. Thus, for frequent therapeutic use, as in cancer treatment, compounds that release Mn should be used with caution.

It is concluded from the present study that replacement of 4/5 of the Mn2+ with Ca2+ more than doubles the in vivo stability of the Mn complex. As obvious from the Results section and Figure 4A, calmangafodipir resulted in significantly and about 40% less retention of Mn in the brain compared to mangafodipir, after repeated dosing at more than 30 times the assumed clinical dose in rats. The total dose in both cases corresponded to approximately 2800 µmol/kg Mn2+ (39 x 72 µmol/kg). These results demonstrate the improved toxicological profile of calmangafodipir in comparison to that of mangafodipir. Furthermore, at equivalent Mn2+ doses, calmangafodipir was significantly more efficacious than mangafodipir to protect BALB/c mice against myelosuppressive effects of the chemotherapy drug oxaliplatin. Importantly, calmangafodipir did not interfere negatively with the antitumor effect of oxaliplatin in CT26 tumor-bearing syngenic BALB/c mice. On the contrary, it increased the antitumor effect of oxaliplatin, in a similar way that has been shown with Teslascan (see below) [12]. The improved in vivo Mn2+ stability of calmangafodipir hence increases its therapeutic index considerably, in comparison to mangafodipir. MnPLED (2 µmol/kg) was, like calmangafodipir, significantly more efficacious than 1.3 and 13.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir to protect WBC, which inevitably suggests that mangafodipir must be dephosphorylated into MnPLED before it can exert in vivo myeloprotective effects, in a similar manner that has previously been demonstrated for its cardioprotective effects [15,25].

From the present data, one cannot fully exclude that the higher content of fodipir in calmangafodipir compared to mangafodipir (at an equivalent Mn dose) may have contributed to its higher efficacy. However, the finding that 13 µmol/kg mangafodipir was less efficacious than 6.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir does not support such a suggestion. Furthermore, a recently published study [15] on myocardial protection of mangafodipir and its metabolite MnPLED against detrimental effects of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) does not indicate any major effect of fodipir or its metabolite PLED. Studies on the cardioprotective effects of mangafodipir and MnPLED in the pig [25] inevitably show that the protective effect is an inherent property of the intact metal complex and not of either dissociated Mn2+ or fodipir/PLED.

In an ideal world, replacement of 4/5 of the Mn2+ with Ca2+ should cause all administered Mn2+ to be excreted in the urine. However, the processes governing the in vivo stability of a metal complex like mangafodipir are indeed complicated and hence difficult to predict exactly. Although readily available Zn2+ is a main player in the dissociation process of Mn2+ from fodipir, other metals present in much higher endogenous concentrations, like Mg2+ and Ca2+, will also influence the in vivo stability of mangafodipir [27]. Furthermore, the stability constants with regard to these metals differ between mangafodipir and its dephosphorylated metabolite MnPLED [26]. Nevertheless, the in vivo stability of Mn2+ in calmangafodipir is double that of Mn2+ in mangafodipir when tested at an Mn2+ dose of 10 µmol/kg, as shown in Figure 3. However, at a more clinically relevant therapeutic dose of Mn2+, i.e., 1 to 2 µmol/kg [17], corresponding to 5 and 10 µmol/kg of calmangafodipir, the relative increase in Mn2+ stability will probably be more pronounced. This presumably explains why calmangafodipir at an equivalent dose of Mn2+ has an efficacy more than double that of mangafodipir, as evident from Figure 5.

Zn2+ is present in all body tissues and fluids. The total body Zn2+ content in humans has been estimated to be 2 to 3 g [31]. Plasma Zn2+ represents about 0.1% of total body Zn2+ content [32], and it is mainly this small fraction of Zn2+ that competes with Mn2+ for binding to fodipir or its dephosphorylated counterparts, DPMP and PLED, after administration. The human body has a high capacity to maintain Zn homeostasis through synergistic adjustments in gastrointestinal absorption and excretion [31]. Clinical phase 1 studies in humans [21] clearly demonstrated that plasma levels of Zn2+ in humans return to baseline within 24 hours after receiving 5 or10 µmol/kg mangafodipir, i.e., a dose expected to consume a similar amount of Zn2+ as that of 6.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir. It is therefore no or a very low risk that repeated injection of clinically relevant doses calmangafodipir should induce Zn deficiency in patients going through chemotherapy, in case of FOLFOX chemotherapy every second week.

Myelosuppression, in particular neutropenia, is a common dose-limiting event during cancer treatment with many chemotherapy drugs, including among others oxaliplatin. Alexandre et al. [14] have recently shown that 10 mg/kg mangafodipir (Teslascan; corresponding to 13.0 µmol/kg) via its SOD mimetic activity protects mice against paclitaxel-induced leukopenia. The present study demonstrates that 6.5 µmol/kg calmangafodipir (corresponding to 1.3 µmol/kg Mn2+) is considerably more efficacious than 1.3 and 13.0 µmol/kg mangafodipir (corresponding to 1.3 and 13.0 µmol/kg Mn2+, respectively) to protect against severe oxaliplatin-induced leukopenia. In all their experiments where Laurent et al. and Alexandre et al. [12,14] used mangafodipir, they actually used the ready-to-use contrast formulation, i.e., Teslascan, which, in addition to 10 mM mangafodipir, also contains 6 mM antioxidant ascorbic acid. Unfortunately, they did not include any ascorbic acid controls in any of their experiments. The present study shows that the Teslascan dose they used in the in vivo experiments, i.e., 10 mg/kg (corresponding to 13.0 µmol/kg), gave more or less identical results as those obtained in the present study with 13 µmol/kg pure mangafodipir. However, in the same papers, they also studied effects of such a high concentration as 400 µM Teslascan (containing 240 µM ascorbic acid) in various in vitro systems, and without any proper ascorbic acid control, it is of course difficult to draw any clear-cut conclusions from such experiments.

It should be stressed that ascorbic acid is added to the ready-to-use formulation of mangafodipir (Teslascan) to avoid oxidation of Mn2+ taking place in the vial during storage. However, after in vivo administration of a clinically relevant dose of Teslascan, ascorbic acid will have no influence on Mn oxidation. It should also be mentioned that a freshly made water solution of mangafodipir is stable with respect to Mn2+ for days without any addition of ascorbic acid. Importantly, during its dismutating action, Mn catalyzes both a one-electron oxidation and a one-electron reduction and is hence electrically neutral [33]. Accordingly, these reactions typically require no external source of redox equivalents and are thus self-contained components of the antioxidant machinery, and there is consequently per se no need of a reducing agent like ascorbic acid.

The previously described myeloprotective effect of Teslascan against paclitaxel showed that decrease of peripheral NEU and LYM is accompanied by a parallel decrease in total bone marrow cells [14], which inevitably suggests that mangafodipir exerts its protective effect at the level of myelopoiesis.

The reason why mangafodipir and calmangafodipir protects nonmalignant cells but damages cancer cells is far from well understood. The present paper and a recent paper by Kurz et al. [15] show that the in vitro cytotoxic activity of mangafodipir is an inherent property of fodipir or its dephosphorylated counterpart PLED alone and not of the intact Mn2+ complex. Speculatively, it may be that cancer cells preferably take up the dissociated form of fodipir or its dephosphorylated counterparts, whereas the intact Mn2+ complex is preferably taken up by non-malignant cells, in analogy with that described for the antioxidant amifostine [34]. When it comes to the in vivo behavior of mangafodipir, it seems, however, reasonable to look for additional/alternative explanations. The complicated in vivo metabolic pattern of mangafodipir, involving stepwise dephosphorylation and Mn2+ release [21], makes it difficult to draw conclusions from in vitro experiments.

Some important clues may be obtained from research aiming to find selective radioprotectants. A body of evidence demonstrates that overexpression of MnSOD protects non-malignant tissues against radiation-induced oxidative stress and, interestingly, simultaneously makes cancer cells more susceptible to radiation [9,10].

However, the experimental and clinical use of SOD enzymes has been restricted due to large molecular weight and poor cellular uptake [35]. To circumvent this limitation experimentally, transgenic animal models have been used to study the radioprotective potential of MnSOD enzymes. These studies have demonstrated that treating radiated animal models with MnSOD, delivered by injection of the enzyme through liposome/viral-mediated gene therapy or insertion of the human MnSOD gene, can ameliorate radiation-induced damage [10,36] and simultaneously make cancerous tissue more susceptible to radiation [9].

It is known that reduced MnSOD expression contributes to increased DNA damage, and cancer cell lines often have diminished MnSOD activity compared to normal counterparts [5,37,38]. Mutations within the MnSOD gene and its regulatory sequence have been observed in several types of human cancers [5,38–40]. In addition to cancer, mutations in MnSOD are associated with cardiomyopathy and neuronal diseases, demonstrating the significant role of MnSOD activity in age-related illnesses [6].

An elevated oxidative status is indispensable for mitogenic stimulation in transformed cells [41]. A number of studies have reported that ROS play an important role in promoting tumor metastasis [8,38,42–45]. These data are consistent with a large body of literature suggesting that the redox balance of many epithelial tumor cells favors an elevated oxidant set point [1], including CT26 cells [12,14]. MnSOD is suppressing cell growth in a variety of cancer cell lines and in mouse models, and the MnSOD growth-retarding functions are at least partially due to triggering of a p53-dependent cellular senescence program [46]. Transfection of human MnSOD cDNA into MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, UACC-903 human melanoma cells, SCC-25 human oral squamous carcinoma cells, U118 human glioma cells, and DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells significantly suppressed their malignant phenotype [40,47–50]. Furthermore, overexpression of MnSOD induced growth arrest in the human colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 and increased senescence that required the induction of p53 [46]. Introduction of the normal MnSOD gene in cancer cells alters the phenotype and the cells lose the ability to form colonies in culture and tumors in nude mice [47].

Although inflammatory processes secondary to oxidative stress damage normal tissue, they may, in fact, be beneficial to tumor tissue by creating growth factor-rich microenvironment and giving the cancerous clones the need to start growing [7,8]. A striking example is the existence of tumor-associated macrophages that accumulate preferentially in the poorly vascularized regions of tumors and secrete cytokines that actually promote tumor growth [8]. Moreover, not only can these cytokines promote tumor growth but they have also been shown to suppress activation of CD8+ T-LYM that are most efficient in tumor elimination. In fact, there is an increasing interest for the importance of T-LYM-mediated immune response for the outcome of cancer chemotherapy [51]. It is known that severe lymphopenia (<1000 cells/µl) negatively affects the chemotherapy response. A collection of mouse cancers, including CT26 colon cancer, MCA205 fibrosarcomas, TSA cell line breast cancers, GOS cell line osteosarcomas, and EL4 thymomas, respond to chemotherapy with doxorubicin and oxaliplatin much more efficiently when they are implanted in syngenic immune-competent mice than in immune-deficient hosts, i.e., nude mice [51]. This is in line with clinical studies revealing that interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)-producing CD8+ T-LYM are potent cancer immune effectors. Furthermore, a high NEU/LYM ratio is associated with a low overall survival for patients with advanced colorectal cancer [52]. Taking into consideration that mangafodipir and in particular calmangafodipir are highly efficient LYM-protecting agents during chemotherapy, it is plausible that this property is of particular importance during in vivo conditions.

From the above discussion, MnSOD appears as an ideal target for adjunct/supportive treatment in connection with chemotherapy and radiotherapy—by simultaneously making cancer cells more susceptible to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and by protecting normal tissue against oxidative damage. Although gene therapy theoretically may offer a therapeutic possibility, cell permeable low molecular weight MnSOD mimetics represent a superior alternative. Kensler et al. described the anticarcinogenic activity of the first generation of a copper superoxide dismutase (CuSOD) mimetic already in 1983 [53]. They were followed by MnSOD mimetics, particularly of the so-called metalloporphyrin, salen, and macrocyclic types, and most recently by the so-called MnPLED derivatives [24,54,55]. A few of the MnSOD mimetics, including the MnPLED derivative mangafodipir, have been tested in patients. In a small phase II translational study, mangafodipir was shown to protect against dose-limiting toxicity of chemotherapy in cancer patients [17].

Taken together, the present study shows a superior therapeutic efficacy of calmangafodipir in comparison to mangafodipir, with respect to selective protection against chemotherapy-induced tissue damage.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden (FORSS-85191). Jan Olof G. Karlsson is one of the founders of PledPharma AB and owns shares in this company. Karlsson is an inventor on two granted patent families (e.g., US6258828 and US6147094) covering the therapeutic use of mangafodipir in cancer, which are owned by GE Healthcare. Karlsson and Rolf G.G. Andersson are inventors on two patent applications (WO2009078794 and WO2011004323) covering the therapeutic use of PLED derivatives in cancer. Andersson is a board member of PledPharma AB and owns shares in the company and has received research funding (less than USD 100,000 during the last 5 years) from PledPharma AB. Karlsson is employed by PledPharma AB and is a former employee of GE Healthcare. Jacques Näsström is employed by PledPharma AB and owns shares in this company. Tino Kurz is an inventor on one patent application (WO2009078794).

References

- 1.Doroshow JH. Redox modulation of chemotherapy-induced tumor cell killing and normal tissue toxicity [editorial] J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:223–225. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridovich I. Oxygen toxicity: a radical explanation. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1203–1209. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal R, Macmillan-Crow LA, Rafferty TM, Saba H, Roberts DW, Fifer EK, James LP, Hinson JA. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice occurs with inhibition of activity and nitration of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;337:110–118. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buettner GR. Superoxide dismutase in redox biology: the roles of super-oxide and hydrogen peroxide. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:341–346. doi: 10.2174/187152011795677544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozden O, Park SH, Kim HS, Jiang H, Coleman MC, Spitz DR, Gius D. Acetylation of MnSOD directs enzymatic activity responding to cellular nutrient status or oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:102–107. doi: 10.18632/aging.100291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anscher MS. Targeting the TGF-β1 pathway to prevent normal tissue injury after cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2010;15:350–359. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kareva I. What can ecology teach us about cancer? Transl Oncol. 2011;4:266–270. doi: 10.1593/tlo.11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urano M, Kuroda M, Reynolds R, Oberley TD, St Clair DK. Expression of manganese superoxide dismutase reduces tumor control radiation dose: gene-radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2490–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borrelli A, Schiattarella A, Mancini R, Morrica B, Cerciello V, Mormile M, d'Alesio V, Bottalico L, Morelli F, D'Armiento M, et al. A recombinant MnSOD is radioprotective for normal cells and radiosensitizing for tumor cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberley LW. Anticancer therapy by overexpression of superoxide dismutase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:461–472. doi: 10.1089/15230860152409095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurent A, Nicco C, Chéreau C, Goulvestre C, Alexandre J, Alves A, Lévy E, Goldwasser F, Panis Y, Soubrane O, et al. Controlling tumor growth by modulating endogenous production of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2005;65:948–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson JOG, Brurok H, Towart R, Jynge P. The magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent mangafodipir exerts antitumor activity via a previously described superoxide dismutase mimetic activity [letter to the editor] Cancer Res. 2006;66:598. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandre J, Nicco C, Chéreau C, Laurent A, Weill B, Goldwasser F, Batteux F. Improvement of the therapeutic index of anticancer drugs by the superoxide dismutase mimic mangafodipir. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:236–244. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurz T, Grant D, Andersson RGG, Towart R, De Cesare M, Karlsson JOG. Effects of MnDPDP and ICRF-187 on doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and anticancer activity. Transl Oncol. 2012;5:252–259. doi: 10.1593/tlo.11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yri OE, Vig J, Hegstad E, Hovde O, Pignon I, Jynge P. Mangafodipir as a cytoprotective adjunct to chemotherapy—a case report. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:633–635. doi: 10.1080/02841860802680427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlsson JO, Adolfsson K, Thelin B, Jynge P, Andersson RG, Falkmer UG. First clinical experience with the magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent and superoxide dismutase mimetic mangafodipir as an adjunct in cancer chemotherapy—a translational study. Transl Oncol. 2012;5:32–38. doi: 10.1593/tlo.11277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedda S, Laurent A, Conti F, Chéreau C, Tran A, Tran-Van Nhieu J, Jaffray P, Soubrane O, Goulvestre C, Calmus Y, et al. Mangafodipir prevents liver injury induced by acetaminophen in the mouse. J Hepatol. 2003;39:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson JOG. Antioxidant activity of mangafodipir is not a new finding [letter to the editor] J Hepatol. 2004;40:872–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheuhammer AM, Cherian MG. Influence of chronic MnCl2 and EDTA treatment on tissue levels and urinary excretion of trace metals in rats. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1982;11:515–520. doi: 10.1007/BF01056081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toft KG, Hustvedt SO, Grant D, Martinsen I, Gordon PB, Friisk GA, Korsmo AJ, Skotland T. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of MnDPDP in man. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:677–689. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Southon TE, Grant D, Bjørnerud A, Moen OM, Spilling B, Martinsen I, Refsum H. NMR relaxation studies with MnDPDP. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:708–716. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wendland MF. Applications of manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) to imaging of the heart. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:581–594. doi: 10.1002/nbm.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brurok H, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Hansson G, Skarra S, Berg K, Karlsson JO, Laursen I, Jynge P. Manganese dipyridoxyl diphosphate: MRI contrast agent with antioxidative and cardioprotective properties? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:768–772. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson JOG, Brurok H, Eriksen M, Towart R, Toft KG, Moen O, Engebretsen B, Jynge P, Refsum H. Cardioprotective effects of the MR contrast agent MnDPDP and its metabolite MnPLED upon reperfusion of the ischemic porcine myocardium. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:540–547. doi: 10.1080/028418501127347340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocklage SM, Cacheris WP, Quay SC, Hahn FE, Raymond KN. Manganese(II) N,N′-dipyridoxylethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetate 5,5-bis (phosphate). Synthesis and characterization of a paramagnetic chelate for magnetic resonance imaging enhancement. Inorg Chem. 1989;28:477–485. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt PP, Toft KG, Skotland T, Andersson K. Stability and transmetallation of the magnetic resonance contrast agent MnDPDP measured by EPR. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s007750100290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni Y, Petré C, Bosmans H, Miao Y, Grant D, Baert AL, Marchal G. Comparison of manganese biodistribution and MR contrast enhancement in rats after intravenous injection of MnDPDP and MnCl2. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:700–707. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, Balmain A, Bruder G, Chaplin DJ, Double JA, Everitt J, Farningham DA, Glennie MJ, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1555–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crossgrove J, Zheng W. Manganese toxicity upon overexposure. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:544–553. doi: 10.1002/nbm.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King JC, Shames DM, Woodhouse LR. Zinc homeostasis in humans. J Nutr. 2000;130:1360S–1366S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1360S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folin M, Contiero E, Vaselli GM. Zinc content of normal human serum and its correlation with some hematic parameters. Biometals. 1994;7:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00205198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culotta VC, Yang M, O'Halloran TV. Activation of super-oxide dismutases: putting the metal to the pedal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuhas JM. Active versus passive absorption kinetics as the basis for selective protection of normal tissues by S-2-(3-aminopropylamino)-ethylphosphorothioic acid. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1519–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Citrin D, Cotrim AP, Hyodo F, Baum BJ, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Radioprotectors and mitigators of radiation-induced normal tissue injury. Oncologist. 2010;15:360–371. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang SK, Rabbani ZN, Folz RJ, Golson ML, Huang H, Yu D, Samulski TS, Dewhirst MW, Anscher MS, Vujaskovic Z. Overexpression of extracellular superoxide dismutase protects mice from radiation-induced lung injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:1056–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberley LW, Buettner GR. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 2003;39:1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C, Zhou HM. The role of manganese superoxide dismutase in inflammation defense. Enzyme Res. 2011:387176. doi: 10.4061/2011/387176. E-pub 2011 Oct 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, Fang F, Dhar SK, Bosch A, St Clair WH, Kasarskis EJ, St Clair DK. Mutations in the SOD2 promoter reveal a molecular basis for an activating protein 2-dependent dysregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase expression in cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1881–1893. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang HJ, Yan T, Oberley TD, Oberley LW. Comparison of effects of two polymorphic variants of manganese superoxide dismutase on human breast MCF-7 cancer cell phenotype. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6276–6283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irani K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ, Der CJ, Fearon ER, Sundaresan M, Finkel T, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Mitogenic signaling mediated by oxidants in Ras-transformed fibroblasts. Science. 1997;275:1649–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cerutti PA. Prooxidant states and tumor promotion. Science. 1985;227:375–381. doi: 10.1126/science.2981433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benhar M, Dalyot I, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. Enhanced ROS production in oncogenically transformed cells potentiates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and sensitization to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6913–6926. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6913-6926.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cullen JJ, Weydert C, Hinkhouse MM, Ritchie J, Domann FE, Spitz D, Oberley LW. The role of manganese superoxide dismutase in the growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1297–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behrend L, Mohr A, Dick T, Zwacka RM. Manganese superoxide dismutase induces p53-dependent senescence in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7758–7769. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7758-7769.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Church SL, Grant JW, Ridnour LA, Oberley LW, Swanson PE, Meltzer PS, Trent JM. Increased manganese superoxide dismutase expression suppresses the malignant phenotype of human melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3113–3117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong W, Oberley LW, Oberley TD, St Clair DK. Suppression of the malignant phenotype of human glioma cells by overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Oncogene. 1997;14:481–490. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu R, Oberley LW, Oberley TD. Transfection and expression of MnSOD cDNA decreases tumor malignancy of human oral squamous carcinoma SCC-25 cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:585–595. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.5-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Li N, Oberley TD, et al. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase in DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells has multiple effects on cell phenotype. Prostate. 1998;35:221–233. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980515)35:3<221::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Immune parameters affecting the efficacy of chemotherapeutic regimens. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:151–160. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chua W, Charles KA, Baracos VE, Clarke SJ. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kensler TW, Bush DM, Kozumbo WJ. Inhibition of tumour promotion by a biomimetic SOD. Science. 1983;221:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.6857269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asplund A, Grant D, Karlsson JOG. Mangafodipir (MnDPDP) and MnCl2-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation in bovine mesenteric arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:609–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miriyala S, Spasojevic I, Tovmasyan A, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, St Clair D, Batinic-Haberle I. Manganese superoxide dismutase, MnSOD and its mimics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:794–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]