Abstract

Autologous cell-based tissue engineering using three-dimensional scaffolds holds much promise for the repair of cartilage defects. Previously, we reported on the development of a porous scaffold derived solely from native articular cartilage, which can induce human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) to differentiate into a chondrogenic phenotype without exogenous growth factors. However, this ASC-seeded cartilage-derived matrix (CDM) contracts over time in culture, which may limit certain clinical applications. The present study aimed to investigate the ability of chemical crosslinking using a natural biologic crosslinker, genipin, to prevent scaffold contraction while preserving the chondrogenic potential of CDM. CDM scaffolds were crosslinked in various genipin concentrations, seeded with ASCs, and then cultured for 4 weeks to evaluate the influence of chemical crosslinking on scaffold contraction and ASC chondrogenesis. At the highest crosslinking degree of 89%, most cells failed to attach to the scaffolds and resulted in poor formation of a new extracellular matrix. Scaffolds with a low crosslinking density of 4% experienced cell-mediated contraction similar to our original report on noncrosslinked CDM. Using a 0.05% genipin solution, a crosslinking degree of 50% was achieved, and the ASC-seeded constructs exhibited no significant contraction during the culture period. Moreover, expression of cartilage-specific genes, synthesis, and accumulation of cartilage-related macromolecules and the development of mechanical properties were comparable to the original CDM. These findings support the potential use of a moderately (i.e., approximately one-half of the available lysine or hydroxylysine residues being crosslinked) crosslinked CDM as a contraction-free biomaterial for cartilage tissue engineering.

Introduction

Trauma, congenital anomalies, and age-related degeneration may contribute to the loss of articular cartilage and, ultimately, to the onset of osteoarthritis. In these cases, tissue regeneration remains a challenging clinical problem because of the limited self-repair capacity of cartilage.1 Current therapies for cartilage injuries include physical procedures such as tissue debridement and microfracture of the subchondral bone, as well as transplantation of autologous or allogeneic osteochondral graftsorchondrocytes.2–6 These procedures can achieve a certain degree of success in some patients, but the clinical outcomes are inconsistent, and further cartilage degeneration is inevitable in most cases.6,7

While significant advances have been made in tissue-engineered repair of articular cartilage, a number of challenges remain in the development of functional cartilage replacements.8 For example, the selection of a cell source for cartilage tissue-engineering strategies is a complicated, yet, critical issue.9 The use of autologous chondrocytes for regenerating or repairing cartilage lesions is available currently as a clinical therapy, but has certain important limitations. The isolation of autologous chondrocytes for human use requires an invasive biopsy procedure to remove a piece of cartilage near the margins of the joint.5,10 Moreover, only a limited number of cells can be harvested, and these primary chondrocytes exhibit poor proliferative capacity with a tendency of phenotypic change upon in vitro expansion.11–13 For these reasons, adult stem cells, which are readily available in significant numbers throughout the body, have been considered as an alternative cell source for tissue-engineering approaches.14–17

Adipose tissue is a known reservoir for multipotent adult stem cells that are easily accessible and can be obtained in abundance through minimally invasive procedures.18,19 During in vitro expansion, adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) maintain a stable, undifferentiated phenotype, similar to other mesenchymal stem cells.20,21 ASCs can also be induced toward a chondrogenic phenotype with growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor 1, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and bone morphogenetic protein 6, making them suitable candidates for cartilage regeneration.14,22–25 However, the use of exogenous growth factors may be impractical for clinical use due to cost or regulatory issues, so a bioactive scaffold that exhibits the appropriate environmental signals may provide an alternative approach for inducing ASC chondrogenesis.

Native extracellular matrix (ECM) is comprised of a complex network of structural and regulatory proteins that are arrayed into a tissue-specific matrix. The multifunctional nature of the native ECM has caught increasing attention in the design and fabrication of tissue-engineering scaffolds. In addition, processed biological tissues have been used as natural biomaterials for tissue repair and tissue engineering.26,27 We previously developed a porous cartilage-derived matrix (CDM) scaffold from porcine articular cartilage that could induce in vitro chondrogenic differentiation of adult human stem cells or chondrocytes without exogenous growth factors.28–30 After 6 weeks of culture, the cellular morphology in the ASC-seeded CDM constructs resembled those in native articular cartilage tissue, with rounded cells residing in the glycosaminoglycan (GAG)-rich regions of the scaffolds. While ASC-seeded CDM scaffolds showed significant synthesis and accumulation of ECM macromolecules as well as the development of mechanical properties approaching those of native cartilage, these constructs also exhibited contraction after long-term culture.28 Contraction of scaffolds has been considered as an important variable in determining the success for chondrogenesis during three-dimensional (3D) culture. Previous in vitro studies using chondrocytes or mesenchymal stem cells in pellets have shown significant contraction of cell pellets over time.31,32 However, this cell-mediated scaffold contraction can lead to disintegration with the surrounding native tissue, which potentially hinders the clinical application of CDM scaffolds for cartilage repair.

As the maintenance of an appropriate atomical geometry of the cell-scaffold complex will be critical for successful cartilage regeneration, we investigated whether crosslinked CDM can resist scaffold contraction while preserving the chondrogenic induction capability of the matrix. Common crosslinking methods for biological scaffolds include dehydrothermal treatment, UV light, and chemical crosslinking.33 While dehydrothermal treatment and UV light invariably result in weaker crosslinking, chemical agents such as glutaraldehyde, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), or photo-oxidizing agents can provide more robust stabilization reactions.31 In this study, we focused on genipin, a natural crosslinker that should prove less toxic relative to other crosslinking agents.34,35

Genipin functions by bridging amino acid groups of lysine or hydroxylysine residues of different polypeptide chains by monomeric or oligomeric crosslinks, resulting in the formation of dark green pigments within the matrix. In several previous studies, genipin has been successfully used to crosslink polymers and biological tissues, including fibrinogen, chitosan, and acellular pericardium.36–38 Using a slightly different approach to cartilage tissue engineering, genipin has also been used in a novel way to crosslink the developing ECM matrix in agarose during chondrogenesis with encouraging results.39 Importantly, genipin has been reported to be 5000–10,000 times less cytotoxic than the chemical crosslinker glutaraldehyde,40 and the biocompatibility of materials crosslinked by genipin is superior to those crosslinked by glutaraldehyde or epoxy compounds.41 Moreover, the genipin-crosslinked materials had comparable mechanical strength and resistance to in vitro enzymatic degradation as that of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked samples.42 We therefore hypothesized that crosslinking CDM with biologically derived genipin would improve scaffold functionality by reducing the magnitude of construct contraction while still inducing chondrogenic differentiation of human ASCs in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of scaffolds

Cartilage was harvested from femoral condyles of skeletally mature female pigs (n=5) shortly after sacrifice, and porous CDM scaffolds were created as previously described.28 Briefly, the cartilage was minced and suspended in distilled water (dH2O), and then homogenized using a tissue homogenizer to form a cartilage slurry. The homogenized tissue suspension was centrifuged; the supernatant removed; and the precipitated tissue particles resuspended in dH2O at a concentration of 0.1 g/mL. Aliquots (5 mL) of the slurry were placed in wells of a six-well plate, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then lyophilized for 24 h. Subsets of the CDM constructs were crosslinked in 0.005%, 0.05%, or 0.5% genipin solution (Wako) at 37°C for 3 days, and subsequently washed with distilled water three times and relyophilized. The unmodified and crosslinked sponge-like CDM scaffolds were cut using a biopsy punch and scalpel to form constructs 6 mm in diameter and ∼2-mm thick. Before use with cells, all scaffolds were sterilized using ethylene oxide and allowed to outgas for 1 week.

The Ninhydrin assay was employed to detect the presence of amine groups in the original and crosslinked CDM scaffolds, thereby defining the extent of genipin-induced modification to the materials. The Ninhydrin reagent (AnaSpec) reacts with free amine groups in the porous scaffolds, producing a purple pigment that can be detected using a spectrophotometer at a maximum wavelength of 560 nm. The degree of crosslinking was defined as the percentage of reacted amines after genipin reaction relative to the free amines in the original, unreacted CDM scaffold.43

Porosity measurement

The porosity of the unseeded scaffolds was determined quantitatively by a liquid displacement method.44 A dry scaffold was transferred into a graduated cylinder containing a known volume (V1) of hexane. The resulting increased fluid volume (V2) was measured by a laser transducer (NAIS; Laser Analog Sensor, LM200; Matsushita Electric Works, Ltd.). After 5 min, the hexane-impregnated scaffolds were removed, and the volume remaining in the graduated cylinder was measured, V3. The porosity of the scaffold was then determined by the ratio of the volume of hexane remaining in the scaffold after removal from the graduated cylinder, (V1 – V3) to the total volume of the scaffold, (V2 – V3).

Scanning electron microscopy

Freeze-dried genipin-crosslinked and unmodified CDM samples were fixed, critical point dried, and then sputter-coated with gold. The prepared scaffolds were viewed with an FEI XL30 Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM). The pore sizes of imaged samples were estimated by tracing the periphery of the pores using Scion Image software (Scion Corp.). We selected scaffold pores with a long-to-short axis ratio of not more than 1.5 for measurements, and the cross-section area of at least 30 pores were estimated for each CDM sample.

Cell culture

Human ASCs (Zen-Bio) were obtained from liposuction waste of subcutaneous adipose tissue from a combination of 7 nonsmoking, nondiabetic female donors with an average age of 41 (range 27–51) and an average body–mass index of 25.17 (range 22.5–28.2). The cells were plated on 225-cm2 culture flasks (Corning) at an initial density of 8000 cells/cm2 in an expansion medium consisting of the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-F-12 (Cambrex Bio Science), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlas Biologicals), 1% penicillin-streptomycin-Fungizone (Gibco), 0.25 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R&D Systems), 5 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Roche Diagnostics), and 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Roche Diagnostics). The cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the medium was changed every 48 h. When the cells reached 90% confluence, they were harvested using 0.05% trypsin and replated.

The ASCs were passaged four times, at which point they were counted with a hemocytometer. The cells were resuspended in a culture medium at 500,000 cells per 30 μL and seeded by pipetting 30 μL directly onto the genipin-crosslinked and noncrosslinked CDM scaffolds. The cell-seeded constructs were placed in 24-well low-attachment plates (Corning) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h to allow the cells to diffuse into and attach to the scaffolds before adding 1 mL of the culture medium in each well with a culture medium consisting of DMEM high-glucose (Gibco), 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), l-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (37.5 μg/mL; Sigma), 1% ITS+Premix (Collaborative Biomedical, Becton Dickinson), and 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma). The medium was changed every 2 to 3 days, and cultures were terminated at defined time points during the study for evaluation.

Visualization of viable cells

At day 2 of culture, human ASCs on the original and genipin-crosslinked CDMs were visualized in situ using confocal microscopy. Live cells were identified using the vital stain Calcein AM (Invitrogen), and the CDM scaffold was elucidated with Texas Red C2-dichlorotriazine (Invitrogen).

Scaffold volume measurement and biochemical analyses

At days 7, 14, and 28, three constructs per time point were harvested, and the volume of the ASC-seeded scaffolds determined quantitatively by liquid displacement. The procedure was similar to the measurement of porosity described previously, but the constructs were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) instead of hexane to determine their volume. Briefly, a known volume (V1) of PBS was poured into a graduated cylinder. Scaffolds were then placed in the cylinder, and the volume was measured as V2 by a laser transducer to detect the change of the fluid level. The total volume of the cell-seeded scaffold was calculated as V2 – V1.

For the biochemical analyses, three blank scaffolds (day 0) and three cell-seeded constructs per time point (day 7, 14, and 28) were enzymatically digested by incubating in 1 mL of papain solution (papain, [125 μL/mL; Sigma], 100 mM phosphate buffer, 10 mM cysteine, and 10 mM EDTA, pH 6.3) for 24 h at 65°C. Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) content was measured fluorometrically using the PicoGreen fluorescent dsDNA assay (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's protocol (excitation wavelength, 485 nm; emission wavelength, 535 nm). GAG content in the samples was measured by the dimethylmethylene blue assay using bovine chondroitin sulfate as a standard. Total collagen content was determined by assaying for hydroxyproline in scaffolds after acid hydrolysis and reaction with p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde and chloramine-T, using 0.134 as the ratio of hydroxyproline to collagen. Both collagen content and GAG content were normalized to dry weight of the scaffolds.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR

Three fresh constructs per time point (1, 7, and 14 days) were transferred into 2-mL microcentrifuge tubes and then snap-frozen, pulverized, and lysed in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated from samples according to the single-step acid-phenol-granidinium method,45 followed by further purification using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA concentration was determined by optical density at 260 nm (OD260) using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop ND-1000).

Once RNA was isolated and purified, complementary DNA was synthesized using iScript reverse transcriptase (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR (iCycler; Bio-Rad) with primer probes purchased from Applied Biosystems was used to compare the transcript levels for 3 different genes: 18s ribosomal RNA (endogenous control; assay ID Hs99999901_s1), aggrecan (ACAN; assay ID Hs00153936_m1), and type II collagen (COL2A1; custom assay: FWD Primer 5-GAGACAGCATGACGCCGAG-3; REV primer 5-GCGGATGCTCTCAATCTGGT-3; Probe 5-FAM-TGGATGCCACACTCAAGTCCCTCAAC-TAMRA-3; assay ID Hs00156568_m1).46 Using plasmids containing the section of the gene of interest (GOI), the starting transcript quantity (SQ) for each respective gene in each sample was determined by the standard curve method. Data were analyzed to determine the ratio of SQ for the GOI to SQ for the housekeeping gene, 18 s, for each sample. This ratio was then normalized to the same quantity measured in day-0 samples of human ASCs. Experiments were run in triplicate for each sample and for each gene.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

CDM constructs were fixed overnight at 4°C in a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, embedded in paraffin, cut into 6-μm-thick sections, and mounted on SuperFrost microscope slides (Microm International AG). For staining of GAGs, sections were treated with hematoxylin for 3 min, 0.02% fast green for 3 min, 0.1% aqueous safranin-O solution for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water, and dehydrated with xylene. Immunohistochemical analysis was also performed on 6-μm sections using monoclonal antibodies to type I collagen (ab6308; Abcam), type II collagen (II-II6B3; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City), type X collagen (C7974; Sigma), and chondroitin 4-sulfate (2B6; gift from Dr. Virginia Kraus, Duke University Medical Center). Digest-All (Zymed) was used for pepsin digestion on sections for type I, II, and X collagen. Sections to be labeled for chondroitin-4-sulfate were treated with trypsin, followed by soybean trypsin inhibitor, and then chondroitinase (all from Sigma). The Histostain-Plus ES Kit (Zymed) was used on sections for serum blocking before secondary antibody labeling (anti-mouse IgG antibody, B7151; Sigma), and subsequent linking to horseradish peroxidase. Aminoethylcarbazole (Zymed) was used as the enzyme substrate/chromogen. The appropriate positive controls for each antibody were prepared and examined to ensure antibody specificity (human cartilage for type II collagen and chondroitin 4-sulfate, subchondral bone for type X collagen, and ligament for type I collagen). Negative controls without primary antibodies were also prepared to rule out nonspecific labeling.

Mechanical testing

Three fresh constructs per time point (0, 14, and 28 days) were collected for mechanical testing. Cylindrical plugs were punched from the central regions of the engineered cartilage tissue on constructs using a biopsy punch to ensure circular geometries for mechanical testing. Creep experiments were conducted in confined compression on an electromechanical material testing system (ELF 3200; Bose).47 Briefly, specimens were placed in a confining chamber in a PBS bath, and compressive loads were applied using a rigid porous platen. After equilibration of a small tare load (1–5 gf), a step compressive load (5–25 gf dependent on time point such that the final equilibrium strain was between 15% and 20%) was applied to the sample and allowed to equilibrate for 2000 s. The compressive aggregate modulus (HA) and hydraulic permeability (k) were determined using a three-parameter, nonlinear least-square regression procedure.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, data were evaluated by analysis of variance and Scheffé's post hoc test using STATA software (Stata, Inc.) to determine significance between different groups and different time points (α=0.05).

Results

Scaffold characteristics

Chemical crosslinking with genipin resulted in a color change from white to green for the cartilage-derived composite constructs, with the most highly crosslinked samples exhibiting the darkest color. Evaluation of free amines by the Ninhydrin assay showed that the crosslinking degree of 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM was up to 89%, while 0.05% and 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM was 50% and 3.5%, respectively. All scaffolds used in these studies were highly porous, as determined by the fluid displacement technique, with measured porosities of 94.7%–95.9% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Crosslinking Degree and Porosity of Cartilage-Derived Matrix Crosslinked by Different Concentrations of Genipin Solution (Data Presented as Mean±Standard Deviation, n=3)

| CDM (0% genipin) | 0.005% genipin-CDM | 0.05% genipin-CDM | 0.5% genipin-CDM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking degree (%) | 0 | 3.5±1.4 | 49.8±5.3 | 89.4±1.3 |

| Porosity (%) | 95.3±2.8 | 95.9±1.2 | 94.7±2.2 | 95.9±1.2 |

CDM, cartilage-derived matrix.

Corroborating the Ninhydrin results, ESEM images showed varying 3D architecture among the CDM scaffolds that was directly related to the different concentrations of genipin solution used for crosslinking (Fig. 1A–D). Interestingly, the pore size of the original CDM (174.9±5.3 μm, mean diameter±standard error of mean) was not statistically different from CDM crosslinked by 0.5% genipin solution (163.8±4.7 μm), though both had significantly larger pores than that of the CDM crosslinked by 0.05% or 0.005% genipin solutions (107.0±3.6 μm and 81.1±2.5 μm, respectively; Fig. 1E). The pore sizes of 0.05% and 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM scaffolds were not statistically different.

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron micrographs and pore size measurement of cartilage-derived matrix (CDM) and crosslinked CDMs. Micrographs of (A) original CDM; (B) 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM; (C) 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM; (D) 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM (scale bar=500 μm). (E) Pore size measurement, data presented as mean diameter±standard error of mean (SEM). Data not sharing the same letter are statistically different from each other (p<0.05, n=30–31).

Cell viability and scaffold volume

Confocal microscopy showed good ASC attachment with a spindle, fibroblast-like morphology on unmodified CDM as well as the 0.005% and 0.05% genipin-treated CDM. Conversely, on scaffolds crosslinked with the highest concentration of genipin, there were few viable ASCs on the matrix surface, and those that did adhere were spherical in shape (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Confocal microscopic images of CDM and crosslinked CDM 2 days after cell seeding. The scaffolds were stained yellow, and the viable adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) were stained green. Abundant ASCs displayed a spindle fibroblast-like morphology on (A) CDM, (B) 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM, and (C) 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM. However, fewer ASCs were seen on (D) 0.5% genipin-treated CDM, and the cell shape appeared more spherical (scale bar=100 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

By day 28, the ASC-seeded scaffolds had become opaque with darkening of their original colors. Grossly, a decrease in the construct volume after 28 days of in vitro culture was evident in the original CDM and 0.005% genipin-treated CDM (Fig. 3). According to the fluid displacement measurement, these ASC-seeded constructs both exhibited significant volume loss from day 7 to day 28 (p<0.05). No obvious contraction was observed in 0.05% or 0.5% genipin-treated CDMs, but the construct volume of the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM was significantly lower than that of the 0.05% genipin-treated CDM at all time points. Although 0.05% and 0.5% genipin-treated CDMs appeared comparable in size after 28 days of culture, there was an appreciable difference in the handling characteristics of the constructs, with the former being firmer than the latter.

FIG. 3.

Volume change of ASC-seeded CDM and crosslinked CDMs. Gross photographs of left to right:unmodified CDM, 0.005%, 0.05%, and 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM at (A) day 0 and (B) after 28 days of culture. The higher the crosslinking degree, the darker the CDM construct appeared. (C) At 28 days of culture, ASC-seeded CDM and 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM constructs showed significant decreases in scaffold volume, while 0.05% and 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDMs revealed no significant volume contraction over the culture period. However, the 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM had a smaller volume than 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM at all time points due to a lack of neomatrix formation within the scaffold. (Data presented as mean±SEM; #p<0.05 between the indicated data; n=3.) Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Biochemical composition

After 7 days of culture, the dsDNA content of ASC-seeded unmodified, 0.005%, and 0.05% genipin-treated CDM constructs significantly increased (ranging from 4.0 to 5.0 μg per sample at day 7, Fig. 4A). However, the ASC-seeded 0.5% genipin-treated CDM remained low in dsDNA content throughout the culture period (0.61 μg at day 0 and 0.24 μg at day 28) with a maximum of 0.98 μg at day 7. This finding suggested that cell viability on the highly crosslinked scaffold was very limited, so the group of the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM was excluded from subsequent GAG and collagen assays. After normalization to dry weight, collagen content in genipin-crosslinked CDM materials as determined by the hydroxyproline assay did not exhibit significant changes over the culture period (Fig. 4B). In the unmodified CDM group, the initial collagen fraction in the matrix (28.8%) significantly decreased for the time period ranging from day 7 (16.0%) today 14 (18.3%), but then gradually increased until it was again similar to the starting value by day 28 (21.8%). However, the normalized collagen content showed no significant difference among all scaffold groups at each time point.

FIG. 4.

Biochemical assays of human ASCs cultured on CDMs with or without genipin crosslinking. (A) Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) content, (B) collagen content normalized by dry weight, and (C) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content normalized by dry weight. Collagen and GAG contents were not measured in the group of the 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM due to lack of neomatrix formation. (Data presented as mean±SEM; *p<0.05 comparing to day 0 data of the same scaffold; #p<0.05 between the indicated data; n=3.)

When compared to the day-0 data, almost all constructs at days 7, 14, and 28 exhibited a decrease of normalized GAG content (Fig. 4C). The original, uncrosslinked CDM had higher normalized GAG content at day 0 (13.9%) compared to 0.005% and 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM constructs (6.5% and 9.4%, respectively). However, because the decrease of GAG content in unmodified CDM was more substantial over the culture period, its normalized GAG content at day 28 (3.2%) was comparable to 0.005% genipin-crosslinked constructs (3.1%), and significantly less than that of the 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM (4.9%).

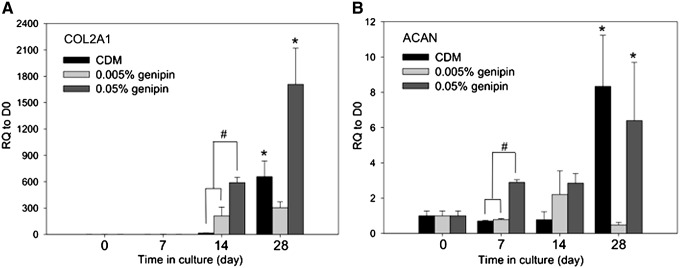

Real time PCR results

The two positive gene markers for chondrogenesis, ACAN and COL2A1, were analyzed in control CDM 0.005%, and 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM groups (Fig. 5). An insufficient amount of RNA was isolated from the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM group precluding further analysis. In comparison to day-0 control cells, significant upregulation of COL2A1 was noted in CDM and 0.05% genipin-treated CDM at day 14 (657-fold and 1708-fold, respectively). Additionally, day-7 COL2A1 transcripts and day-1 ACAN transcripts were significantly higher in 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM than the other two groups. On day 14, ACAN transcripts increased 8.3-fold in unmodified CDM and 6.4-fold in 0.05% genipin-treated CDM constructs relative to day-0 controls with statistical significance. However, in the 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM group, ACAN expression was not significantly varied during the course of the study.

FIG. 5.

Expression of cartilaginous transcripts in CDM matrices. Relative quantification (RQ) of (A) COL2A1 and (B) ACAN gene expression normalized to day 0 transcript values revealed upregulation of both genes in the CDM and the 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM on day 14. RQ of COL2A1 and ACAN gene expression was not measured in the group of 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM due to the lack of cell proliferation. (Data presented as mean±SEM; *p<0.05 comparing to day 0 data of the same scaffold; #p<0.05 between the indicated data; n=3–4.)

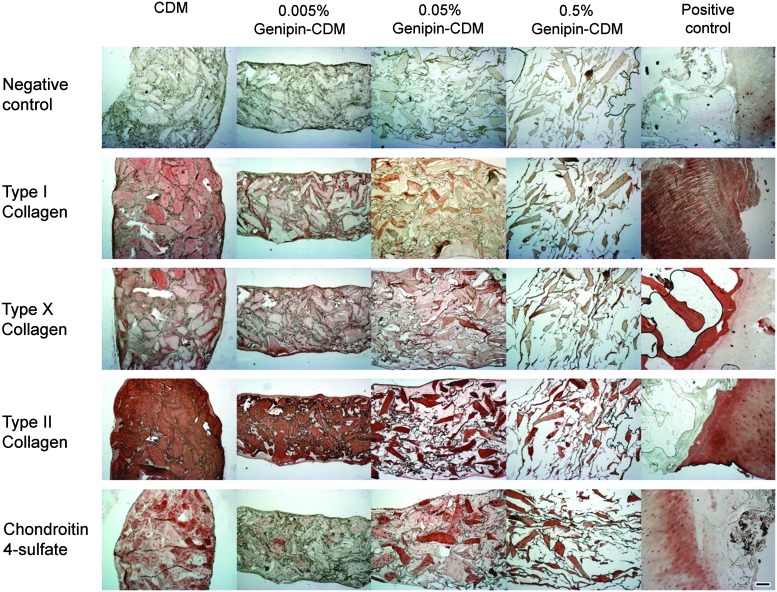

Histology and immunohistochemistry

By day 28, the ASC-seeded 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM scaffolds showed virtually no new ECM deposition as determined by Safranin-O/fast green staining. The microscopic morphology of the scaffold was very similar to a blank construct on day 0. In contrast, the sparse, porous scaffolds became nearly completely filled with neomatrix in the other three groups (Fig. 6). Moreover, immunohistochemistry on day 28 revealed labeling for the chondroitin-4-sulfate epitope throughout the constructs of the control CDM and 0.05% genipin-treated CDM groups, though chondroitin-4-sulfate immunolabeling was not as prevalent in scaffolds crosslinked with the 0.005% genipin solution. Type II collagen, the primary collagen of articular cartilage, was found in abundance throughout the matrix interstitial voids in the unmodified and 0.005% genipin-treated CDM. In the group exposed to 0.05% genipin solution, positive reaction with type II collagen was not pervasive, but instead appeared more concentrated in certain areas of the construct. The presence of type I collagen, a negative marker for chondrogenesis, was also noted in all constructs, although at a much lower intensity than that of type II collagen. Type X collagen, a cartilage hypertrophic phenotypic marker, was similarly evident within the collagenous matrix in all constructs at day 28 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Safranin O/fast green staining. Blank constructs with different crosslinking degrees all showed porous structures on day 0. After cell culture for 28 days, abundant neomatrix developed in all groups, except the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM (scale bar=200 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

FIG. 7.

Day-28 immunohistochemistry results of the ASC-seeded CDM and genipin-crosslinked CDMs. Intense positive labeling for chondroitin-4-sulfate and collagen type II was observed in the CDM and the 0.05% genipin-treated CDM, though the distribution of positively stained area varied. Positive controls for immunohistochemistry were human ligament for collagen I antibody, and human osteochondral sections for other antibodies (scale bar=200 μm). Within the interstices of the heavily stained CDM lies the ASC-deposited neomatrix, which is also stained positive for type II collagen and chondroitin-4-sulfate. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Mechanical testing

An increasing compressive aggregate modulus (HA) was demonstrated with increasing crosslinking percentage at D0, which was only significant with the high crosslinking percentage in the group of 0.5% genipin. (HA=0.089 MPa, p<0.05). However, no significant differences were noted among the groups at days 14 or 28 (Fig. 8A). The compressive aggregate moduli of these constructs ranged from 0.035 to 0.048 MPa at day 28. The hydraulic permeability (k) was 1.74 mm4/(N·s) at day 28 for 0.5% genipin-treated CDM, which was significantly higher than the values for the other three groups, which ranged from 0.009 to 0.019 mm4/(N·s) (Fig. 8B). No significant difference in hydraulic permeability was noted among the remaining three groups at day 14 or 28. Note that the hydraulic permeability could not be calculated from the biphasic model at day 0 due to the high porosity of the CDM scaffolds.

FIG. 8.

(A) Aggregate modulus (HA) and (B) hydraulic permeability (k) of human ASC-seeded CDM and genipin-crosslinked CDM scaffolds at days 0, 14, and 28 of culture. The hydraulic permeability could not be calculated from the biphasic model at day 0 due to the high porosity of the CDM scaffolds. (Data presented as mean±standard deviation; *p<0.05 versus other groups at the same time point; n=3.)

Discussion

Many processed natural derivatives have been used as biomaterials for tissue repair and tissue engineering.48 ECM proteins are generally well conserved among different species and, as such, may provide the opportunity for use as functional scaffolds for cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation.26,27,29,36,49 We previously showed that CDM, a porous scaffold derived from articular cartilage, is capable of inducing chondrogenic differentiation of ASCs without exogenous growth factors.28 By crosslinking the CDM in a genipin solution (0.5%, 0.05% and 0.005%) at 37°C for 3 days, constructs were produced that were microscopically unique relative to noncrosslinked CDM, though similar to the unmodified matrix, genipin-crosslinked materials were highly porous (94.7%–95.9%). CDM crosslinked with a 0.5% genipin solution had comparable pore size to the original CDM, while 0.005% or 0.05% genipin-treated CDMs had significantly smaller pore sizes. This result suggests that the CDM underwent certain remodeling processes when crosslinked by genipin solution of lower concentration, though the mechanism by which the pore structure was altered is unknown. It was possible that the use of 0.5% genipin induced relatively rapid crosslinking, potentially resulting in an ESEM presentation substantially similar to the noncrosslinked control samples. Scaffolds with smaller pores have a greater surface area, which provides increased sites for cell attachment after seeding.50 Moreover, scaffold pore size and pore shape have been shown to play an important role in the chondrogenic process both in vitro and in vivo.51,52 Accordingly, this pore size difference may partially account for the differential behavior of ASCs in the crosslinked scaffolds.

The integration of tissue-engineered scaffolds with surrounding native tissue is crucial for both immediate functionality and long-term performance of the tissue, as the scaffold must maintain the appropriate anatomical geometry to serve in its functional capacity.53 This consistency is particularly crucial for articular cartilage repair because the surrounding native cartilage has a low regeneration potential.1,8 Contraction of engineered cartilage in vivo would invariably create a gap between the construct and the nearby native cartilage or bone tissue, and possibly even result in the dislodgement of the construct. In the present study, both the original CDM and 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM yielded significant construct contraction after 28 days of in vitro culture (up to 24% reduction in volume). However, increasing the genipin solution concentration to 0.05% or 0.5% resulted in crosslinked CDMs with virtually no volume reduction over a culture period of up to 28 days. Vickers et al. investigated the effect of crosslink density on scaffold contraction and chondrogenesis in a model of adult canine articular chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen–GAG scaffolds.31 Their results were consistent with our study in that scaffolds with low crosslinking density experienced cell-mediated contraction and increased cell density. However, they also found the chondrogenic activity of the chondrocytes being inversely related to the crosslinking degree within the collagen–GAG scaffolds, leading to a hypothesis that the resistance to cell-mediated contraction may have ultimately limited chondrogenesis to some degree in that scaffold.31 This hypothesis is not completely consistent with our results, which showed that CDM scaffolds with a crosslinking degree up to 50% effectively allowed ASC proliferation and a level of chondrogenesis similar to the control CDM group while resisting scaffold contraction, suggestive of an amount of modification that maintains geometry without inhibiting tissue formation. It is important to note that the type of cell is an important factor in determining the differentiation potential on a given scaffold, and to this end, different cells, such as chondrocytes, embryonic stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells, may produce differential outcomes in 3D culture, presumably due to variations in cell surface ligand expression and overall cell–matrix interactions.54 Moreover, except for the major components of native cartilage, namely type II collagen and GAG, the endogenous content of organic ECM molecules and cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins could distinguish CDM scaffolds from synthetic type II collagen–GAG scaffolds employed in the Vicker study.31,55

A recent study showed that the properties of the genipin-crosslinked chitosan/collagen scaffolds can be greatly affected by different genipin concentrations.56 We also found that excessive crosslinking by 0.5% genipin solution resulted in poor cell attachment, demonstrated by the paucity of cells and the round cell shape on the scaffold surface 2 days after cell seeding. Further analysis of dsDNA content revealed virtually no cell viability in the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM throughout the culture period. Moreover, the measured volume of the ASC-seeded 0.5% genipin-treated CDM at day 28 was significantly lower than that of the 0.05% genipin-treated CDM despite a comparable gross construct size. This volume corresponded to the histological finding of no substantial new tissue formation within the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM constructs after 4 weeks of culture. With a crosslinking degree up to 89%, a significant number of adhesion domains in the CDM may have been altered in the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM, resulting in the failure of ASC adherence to the scaffold. Such a lack of bonding sites is a more likely explanation for the inability of the highly crosslinked scaffolds to support chondrogenesis, in contrast to potential cytotoxicity of genipin. Previous studies have reported very low cytotoxicity of genipin,36 and furthermore, ASCs in the 0.05% and 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM showed comparable proliferative capability with respect to the noncrosslinked CDM. Therefore, due to the lack of a dose-dependent toxic effect, it was unlikely that the residual genipin in these crosslinked CDMs caused significant cellular toxicity.

Modified CDM treated by genipin solution with lower concentrations (0.05% and 0.005%) not only supported ASC proliferation in the scaffolds, but also maintained its potential to induce chondrogenic differentiation of ASCs. Noncrosslinked CDM had higher normalized GAG content at day 0, probably because genipin-crosslinked CDM had lost some GAG into the genipin solution during the crosslinking process. Subsequently, during in vitro culture, normalized collagen and GAG content within the 0.05% or 0.005% genipin-crosslinked CDM constructs were comparable to the noncrosslinked CDM. CDM crosslinked by 0.05% genipin even exhibited a higher normalized GAG content at day 28, indicative of the functional nature of the ASC-derived chondrocytes within these matrices. Moreover, gene transcript levels on day 14 for aggrecan (ACAN), the large aggregating proteoglycan found in articular cartilage, and type II collagen (COL2A1), the principal collagen found in articular cartilage, were upregulated in the CDM and 0.05% genipin-crosslinked CDM groups. In accordance with our previous study,28 ASCs seeded on CDM did not show upregulation of the COL2A1 gene until day 14. However, the 0.05% genipin-treated CDM already exhibited significant upregulation of COL2A1 relative to the CDM at day 7, and it subsequently led to a 1708-fold increase of transcript number at day 14. Further considering the absence of COL2A1 transcripts in ASCs at day 0, the significant upregulation of COL2A1 suggested that the CDM did not lose its chondrogenic potential after crosslinking with a 0.05% genipin solution.

During monolayer expansion, ASCs synthesize type I collagen, which also increases during chondrogenic differentiation culture.23,57 Except for the lack of new ECM formation in 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM, histological and immunohistochemical sections in all other crosslinking concentrations showed a fibrocartilaginous phenotype on day 28, characterized by the coexpression of both type I and type II collagen. However, the distribution pattern of the positively stained area of type I and type II collagen was quite different among the groups. On one hand, the ASC-seeded noncrosslinked CDM appeared more uniformly and homogenously stained for type I and type II collagen. On the other hand, type I and type II collagen appeared more heterogeneous in the 0.05% and 0.005% genipin-treated CDM groups. Type I collagen was primarily located in regions between the larger masses within new matrix formation, while type II collagen was more dominant in these larger masses. Therefore, genipin crosslinking not only affected the contraction of CDM scaffold over the culture period, it also altered the ECM deposition pattern in these scaffolds. This hypothesis was further supported by our immunohistochemistry data of chondroitin-4-sulfate, which demonstrated extensive positive labeling on day 28 of culture, in both the original CDM and 0.05% genipin-treated CDM group. However, the sections of the 0.005% genipin-treated CDM were only faintly stained, which corresponded to its absence of ACAN gene upregulation on day 14. It is intriguing that a relatively mild crosslinking of the CDM inhibited the formation of chondroitin-4-sulfate by ASCs, while a higher degree of crosslinking reversing this inhibitory effect. The underlying mechanism related to proteoglycan synthesis and accumulation will require further investigation.

Biomechanical properties of tissue-engineered cartilage are critical outcome measures for functional tissue engineering.58 At day 0, the 0.5% genipin-crosslinked CDM exhibited significantly a higher aggregate modulus comparing to other groups. However, after 14 and 28 days of culture, although the crosslinking degree of CDM still appeared to correlate with the aggregate modulus of the ASC-seeded CDM, the difference was not statistically significant. The finding corresponded to the lack of neomatrix formation in the group of 0.5% genipin, resulting in gradual scaffold degradation and decreased mechanical strength. In the other groups of original or crosslinked CDM, the matrix deposited by seeded ASCs replenished the degrading CDM scaffolds over the culture period and maintained the level of their aggregate moduli. On day 28, the aggregate moduli ranged from 35 to 48 kPa in the original and genipin-crosslinked CDM. The value of native articular cartilage is on the order of 500–900 kPa,59 most likely indicating that the 4-week culture period in this study was not long enough to promote sufficient ECM biosynthesis for improving the biomechanical properties. In our previous study of ASC-seeded CDM, the aggregate modulus was shown to be significantly improved after 42 days in culture.28 Although even with 42 days of culture, it is likely that the tissue will need to be reinforced to attain functional biomechanical properties, as we have recently reported.60 Applying mechanical stimuli during ASC culture on the genipin-crosslinked CDM may be beneficial to the mechanical properties of these cell-seeded constructs as has been previously reported for dynamically loaded chondrocyte-laden agarose disks, resulting in a sixfold increase in the equilibrium aggregate modulus after 28 days of loading.61

The high hydraulic permeability of the 0.5% genipin-treated CDM resulted from poor cell attachment and, consequently, the lack of neomatrix formation throughout the culture period. ECM accumulation in the other groups was concurrent with a decrease in the permeability values, with no significant differences reported among the different groups. The use of bioreactors may prove useful in this system to increase nutrition transport in tissue-engineered constructs and consequently enhance cell growth and differentiation in the genipin-crosslinked CDM scaffolds.

In an animal study with crosslinked acellular bovine pericardia, Liang et al. showed that crosslinking degree determined the degradation rate of acellular tissue and its tissue regeneration pattern.62 Moreover, chemical crosslinking of xenogeneic or allogeneic ECM scaffolds may elicit an undesired immunogenic response.63 Therefore, additional in vivo evaluation is necessary to fully recognize the clinical implication of our observations in the present study. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated that ASCs behaved differently in CDM constructs with different crosslinking degrees. While excessive crosslinking of the CDM diminished cell attachment and proliferation, we found that the 0.05% genipin solution was the ideal crosslinking percentage of those evaluated, resulting in scaffolds with a degree of crosslinking at 50%. Finally, our findings suggest that a crosslinked scaffold using the 0.05% genipin solution, which resulted in a 50% degree of crosslinking, not only supported ASC proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation during in vitro culture, but it also prevented cell-mediated construct contraction, a critical feature of tissue-engineered constructs that will be necessary for geometry maintenance for in vivo cartilage repair applications.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Melissa McHale for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants AG15768, AR50245, AR48182, AR48852, and AR057600, and grants from the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH. 100–1690 and 101–1962).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Guilak F. Hung C.T. Physical regulation of cartilage metabolism. In: Mow V.C., editor; Huiskes R., editor. Basic Orthopaedic Biomechanics and Mechano-Biology. 3rd. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 259–300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgaertner M.R. Cannon W.D., Jr. Vittori J.M. Schmidt E.S. Maurer R.C. Arthroscopic debridement of the arthritic knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson L.L. Arthroscopic abrasion arthroplasty: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:S306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breinan H.A. Minas T. Hsu H.P. Nehrer S. Sledge C.B. Spector M. Effect of cultured autologous chondrocytes on repair of chondral defects in a canine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1439. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199710000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittberg M. Lindahl A. Nilsson A. Ohlsson C. Isaksson O. Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knutsen G. Engebretsen L. Ludvigsen T.C. Drogset J.O. Grontvedt T. Solheim E., et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation compared with microfracture in the knee. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:455. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mobasheri A. Csaki C. Clutterbuck A.L. Rahmanzadeh M. Shakibaei M. Mesenchymal stem cells in connective tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: applications in cartilage repair and osteoarthritis therapy. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:347. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guilak F. Butler D.L. Goldstein S.A. Functional tissue engineering—the role of biomechanics in articular cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;391:S295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghunath J. Salacinski H.J. Sales K.M. Butler P.E. Seifalian A.M. Advancing cartilage tissue engineering: the application of stem cell technology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:503. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H.A. Suh D.I. Song Y.W. Relationship between chondrocyte apoptosis and matrix depletion in human articular cartilage. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonaventure J. Kadhom N. Cohen-Solal L. Ng K.H. Bourguignon J. Lasselin C., et al. Reexpression of cartilage-specific genes by dedifferentiated human articular chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:97. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokes D.G. Liu G. Coimbra I.B. Piera-Velazquez S. Crowl R.M. Jimenez S.A. Assessment of the gene expression profile of differentiated and dedifferentiated human fetal chondrocytes by microarray analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:404. doi: 10.1002/art.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thirion S. Berenbaum F. Culture and phenotyping of chondrocytes in primary culture. Methods Mol Med. 2004;100:1. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-810-2:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y. Kim U.J. Blasioli D.J. Kim H.J. Kaplan D.L. In vitro cartilage tissue engineering with 3D porous aqueous-derived silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7082. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wayne J.S. McDowell C.L. Shields K.J. Tuan R.S. In vivo response of polylactic acid-alginate scaffolds and bone marrow-derived cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:953. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Y. Hu Y. Hao W. Han Y. Meng G. Zhang D., et al. A novel injectable scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering using adipose-derived adult stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:27. doi: 10.1002/jor.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams C.G. Kim T.K. Taboas A. Malik A. Manson P. Elisseeff J. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a photopolymerizing hydrogel. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:679. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes B.T. Diekman B.O. Gimble J.M. Guilak F. Isolation of adipose-derived stem cells and their induction to a chondrogenic phenotype. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1294. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guilak F. Lott K.E. Awad H.A. Cao Q. Hicok K.C. Fermor B., et al. Clonal analysis of the differentiation potential of human adipose-derived adult stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:229. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng N.C. Wang S. Young T.H. The influence of spheroid formation of human adipose-derived stem cells on chitosan films on stemness and differentiation capabilities. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1748. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estes B.T. Wu A.W. Storms R.W. Guilak F. Extended passaging, but not aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, increases the chondrogenic potential of human adipose-derived adult stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:987. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson G.R. Gimble J.M. Franklin D.M. Rice H.E. Awad H. Guilak F. Chondrogenic potential of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:763. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estes B.T. Wu A.W. Guilak F. Potent induction of chondrocytic differentiation of human adipose-derived adult stem cells by bone morphogenetic protein 6. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1222. doi: 10.1002/art.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann S. Knecht S. Langer R. Kaplan D.L. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Merkle H.P., et al. Cartilage-like tissue engineering using silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2729. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilak F. Estes B.T. Diekman B.O. Moutos F.T. Gimble J.M. 2010 Nicolas Andry Award: Multipotent adult stem cells from adipose tissue for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2530. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1410-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ott H.C. Matthiesen T.S. Goh S.K. Black L.D. Kren S.M. Netoff T.I., et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urist M.R. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150:893. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3698.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng N.C. Estes B.T. Awad H.A. Guilak F. Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived adult stem cells by a porous scaffold derived from native articular cartilage extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:231. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng N.C. Estes B.T. Young T.H. Guilak F. Engineered cartilage using primary chondrocytes cultured in a porous cartilage-derived matrix. Regen Med. 2011;6:81. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diekman B.O. Estes B.T. Guilak F. The effects of BMP6 overexpression on adipose stem cell chondrogenesis: Interactions with dexamethasone and exogenous growth factors. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2010;93:994. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers S.M. Squitieri L.S. Spector M. Effects of cross-linking type II collagen-GAG scaffolds on chondrogenesis in vitro: dynamic pore reduction promotes cartilage formation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1345. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang S. Spector M. Incorporation of hyaluronic acid into collagen scaffolds for the control of chondrocyte-mediated contraction and chondrogenesis. Biomed Mater. 2007;2:S135. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/2/3/S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badylak S.F. The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:377. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L.L. Sung H.W. Tsai C.C. Huang D.M. Biocompatibility study of a biological tissue fixed with a naturally occurring crosslinking reagent. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;42:568. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19981215)42:4<568::aid-jbm13>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y. Hsu C.K. Wei H.J. Chen S.C. Liang H.C. Lai P.H., et al. Cell-free xenogenic vascular grafts fixed with glutaraldehyde or genipin: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Biotechnol. 2005;120:207. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang Y. Lee M.H. Liang H.C. Hsu C.K. Sung H.W. Acellular bovine pericardia with distinct porous structures fixed with genipin as an extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:881. doi: 10.1089/1076327041348509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sell S.A. Francis M.P. Garg K. McClure M.J. Simpson D.G. Bowlin G.L. Cross-linking methods of electrospun fibrinogen scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:45001. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/4/045001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva S.S. Motta A. Rodrigues M.T. Pinheiro A.F. Gomes M.E. Mano J.F., et al. Novel genipin-cross-linked chitosan/silk fibroin sponges for cartilage engineering strategies. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2764. doi: 10.1021/bm800874q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lima E.G. Tan A.R. Tai T. Marra K.G. DeFail A. Ateshian G.A., et al. Genipin enhances the mechanical properties of tissue-engineered cartilage and protects against inflammatory degradation when used as a medium supplement. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2009;91:692. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cauich-Rodriguez J.V. Deb S. Smith R. Effect of cross-linking agents on the dynamic mechanical properties of hydrogel blends of poly(acrylic acid)-poly(vinyl alcohol-vinyl acetate) Biomaterials. 1996;17:2259. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung H.W. Huang R.N. Huang L.L. Tsai C.C. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxicity of a naturally occurring cross-linking reagent for biological tissue fixation. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1999;10:63. doi: 10.1163/156856299x00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung H.W. Huang R.N. Huang L.L. Tsai C.C. Chiu C.T. Feasibility study of a natural crosslinking reagent for biological tissue fixation. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;42:560. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19981215)42:4<560::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stryer L. Biochemistry. 3rd. New York: Freeman; 1988. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim U.J. Park J. Kim H.J. Wada M. Kaplan D.L. Three-dimensional aqueous-derived biomaterial scaffolds from silk fibroin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2775. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chomczynski P. Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:581. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehlhorn A.T. Niemeyer P. Kaiser S. Finkenzeller G. Stark G.B. Sudkamp N.P., et al. Differential expression pattern of extracellular matrix molecules during chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2853. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mow V.C. Kuei S.C. Lai W.M. Armstrong C.G. Biphasic creep and stress-relaxation of articular-cartilage in compression—theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badylak S.F. The extracellular matrix as a biologic scaffold material. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3587. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little D. Guilak F. Ruch D.S. Ligament-derived matrix stimulates a ligamentous phenotype in human adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2307. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Brien F.J. Harley B.A. Yannas I.V. Gibson L.J. The effect of pore size on cell adhesion in collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:433. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeong C.G. Zhang H. Hollister S.J. Three-dimensional poly(1,8-octanediol-co-citrate) scaffold pore shape and permeability effects on sub-cutaneous in vivo chondrogenesis using primary chondrocytes. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:505. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamane S. Iwasaki N. Kasahara Y. Harada K. Majima T. Monde K., et al. Effect of pore size on in vitro cartilage formation using chitosan-based hyaluronic acid hybrid polymer fibers. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2007;81:586. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D.A. Varghese S. Sharma B. Strehin I. Fermanian S. Gorham J., et al. Multifunctional chondroitin sulphate for cartilage tissue-biomaterial integration. Nat Mater. 2007;6:385. doi: 10.1038/nmat1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seda Tigli R. Ghosh S. Laha M.M. Shevde N.K. Daheron L. Gimble J., et al. Comparative chondrogenesis of human cell sources in 3D scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:348. doi: 10.1002/term.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed N. Dreier R. Gopferich A. Grifka J. Grassel S. Soluble signalling factors derived from differentiated cartilage tissue affect chondrogenic differentiation of rat adult marrow stromal cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:665. doi: 10.1159/000107728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bi L. Cao Z. Hu Y. Song Y. Yu L. Yang B., et al. Effects of different cross-linking conditions on the properties of genipin-cross-linked chitosan/collagen scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:51. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hennig T. Lorenz H. Thiel A. Goetzke K. Dickhut A. Geiger F., et al. Reduced chondrogenic potential of adipose tissue derived stromal cells correlates with an altered TGFbeta receptor and BMP profile and is overcome by BMP-6. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:682. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butler D.L. Goldstein S.A. Guilak F. Functional tissue engineering: the role of biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:570. doi: 10.1115/1.1318906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Athanasiou K.A. Rosenwasser M.P. Buckwalter J.A. Malinin T.I. Mow V.C. Interspecies comparisons of in situ intrinsic mechanical properties of distal femoral cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:330. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moutos F.T. Estes B.T. Guilak F. Multifunctional hybrid three-dimensionally woven scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10:1355. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mauck R.L. Soltz M.A. Wang C.C. Wong D.D. Chao P.H. Valhmu W.B., et al. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:252. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liang H.C. Chang Y. Hsu C.K. Lee M.H. Sung H.W. Effects of crosslinking degree of an acellular biological tissue on its tissue regeneration pattern. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3541. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Badylak S.F. Gilbert T.W. Immune response to biologic scaffold materials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:109. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]