Abstract

The present study addressed adult human mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation toward the osteoblastic lineage in response to alternating electric current, a biophysical stimulus. For this purpose, MSCs (chosen because of their proven capability for osteodifferentiation in the presence of select bone morphogenetic proteins) were dispersed and cultured within electric-conducting type I collagen hydrogels, in the absence of supplemented exogenous dexamethasone and/or growth factors, and were exposed to either 10 or 40 μA alternating electric current for 6 h per day. Under these conditions, MSCs expressed both early- (such as Runx-2 and osterix) and late- (specifically, osteopontin and osteocalcin) osteogenic genes as a function of level, and duration of exposure to alternating electric current. Compared to results obtained after 7 days, gene expression of osteopontin and osteocalcin (late-osteogenic genes) increased at day 14. In contrast, expression of these osteogenic markers from MSCs cultured under similar conditions and time periods, but not exposed to alternating electric current, did not increase as a function of time. Most importantly, expression of genes pertinent to the either adipogenic (specifically, Fatty Acid Binding Protein-4) or chondrogenic (specifically, type II collagen) pathways was not detected when MSCs were exposed to the aforementioned alternating electric-current conditions tested in the present study. The present research study was the first to provide evidence that alternating electric current promoted the differentiation of adult human MSCs toward the osteogenic pathway. Such an approach has the yet untapped potential to provide critically needed differentiated cell supplies for cell-based assays and/or therapies for various biomedical applications.

Introduction

Progress in developing clinically relevant biomedical applications (such as regeneration and repair of damaged tissues) using pluripotent stem cells has been slow, because the conditions to generate either the required numbers of undifferentiated cells or lineage-specific cells remain, at best, partially understood. Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into a specific phenotype is a most sought-after outcome for advancing bone-related tissue engineering and tissue regeneration applications of these most promising cells.

To date, biochemical compounds (e.g., dexamethasone and bone morphogenetic proteins [BMPs]) have been utilized to promote differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (which have the potential to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes) exclusively into osteoblasts. In contrast, current knowledge of the effects of biophysical stimuli on the cellular and molecular functions (including underlying mechanisms) of adult human MSCs and their differentiation into osteoblasts is nonexistent. Justification for such a direction in research endeavors is provided by the physiological milieu: bone and its constituent cells exist, and function, in an environment composed of biochemical as well as by biophysical (specifically, mechanical and electrical) stimuli.

The present in vitro study addressed the need for novel strategies that reliably induce MSC differentiation into specific cell types and, for this purpose, used a multidisciplinary approach that encompassed aspects of cellular engineering, molecular biology, biochemistry, and tissue engineering. This is the first study to provide evidence that exposure to alternating electric current alone (i.e., in the absence of supplemented exogenous dexamethasone and growth factors) induces differentiation of adult human MSCs toward the osteogenic (and neither the chondrogenic nor adipogenic) phenotype.

Materials and Methods

MSC culture

Cryopreserved adult human MSCs from normal human bone marrow (withdrawn from the posterior iliac crest of the pelvic bone) were obtained commercially (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.). These MSCs were characterized by the vendor and used as received with no further characterization.

MSCs were cultured in a growth medium (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.) consisting of an MSC basal medium supplemented with serum, l-glutamine, and gentamicin/amphotericin-B (concentrations of which are considered proprietary information from, and were not disclosed by, the vendor) under standard cell culture conditions, that is, a sterile, humidified, 37°C, 95% air/5% CO2 environment.

MSC passage numbers 3–5 were used in all experiments.

Preparation of collagen hydrogel constructs

High concentration rat-tail Type I collagen (dissolved in acetic acid) was commercially obtained (BD Biosciences). Collagen hydrogels were prepared with a final collagen concentration of 5 mg/mL by adding 1 N sodium hydroxide, 10×phosphate-buffered saline, and MSC growth medium (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.) consisting of MSC basal medium supplemented with serum, l-glutamine, and gentamicin/amphotericin-B in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Human MSCs (250,000 cells per hydrogel) were dispersed throughout each collagen solution before gelation at 37°C. Three-dimensional, cylindrical (0.3-cm height and 1.4-cm diameter) hydrogel constructs were thus obtained in 30 min.

Exposure of MSCs to BMPs

Human recombinant BMP-2 and BMP-6 (R&D Systems) at final concentrations of 25 and 100 ng/mL were each one added to separate collagen solutions (containing 250,000 MSCs per hydrogel; prepared as described in the Preparation of collagen hydrogel constructs section) before hydrogel gelation. The same concentrations of the respective BMPs were also added to the supernatant cell culture growth medium (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.) consisting of an MSC basal medium supplemented with serum, l-glutamine, and gentamicin/amphotericin-B. No other supplemental biochemicals (such as dexamethasone) were added either to the collagen hydrogel constructs or to the surrounding medium during these experiments. The medium was initially changed 24 h after MSCs were dispersed within the collagen hydrogel constructs and then changed every 3 days throughout the duration of the experiments (up to 14 days). Controls were MSCs cultures dispersed within collagen hydrogel constructs under similar culture conditions, but not exposed to BMPs. Experiments were run as single samples and repeated at three separate times.

Alternating electric current laboratory setup

Cells, cultured in vitro (as described in the MSC culture section) within the hydrogel constructs (prepared as described in the Preparation of collagen hydrogel constructs section), were exposed to alternating electric current using a laboratory setup (Fig. 1) modified from the system designed by Ulmann1 and used by Supronowicz et al.2 For this purpose, collagen solutions (either with or without cells) were poured into each individual cell chamber directly onto the indium tin oxide (ITO) glass and thus formed direct contact with that substrate when the hydrogel solidified in situ.

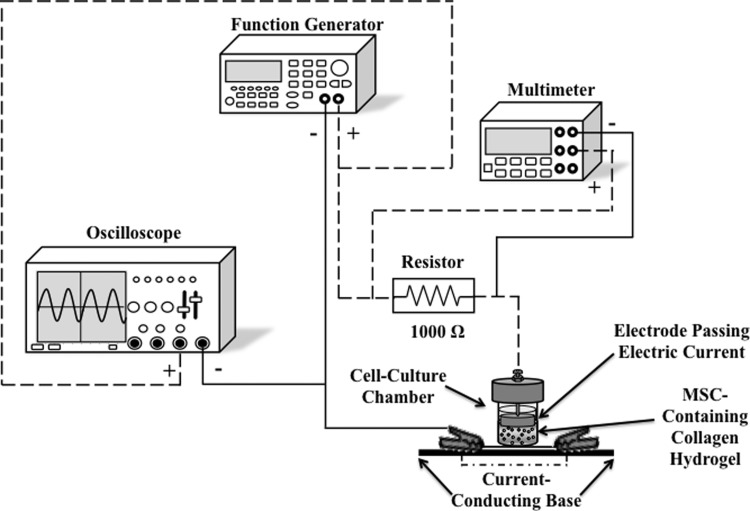

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration (not to scale) of the alternating electric current laboratory system (modified from an original design by Ulmann1 and setup by Supronowicz2). This system consisted of a function generator, multimeter, oscilloscope, resistor, and cathode. Dashed lines represent positive electrical connections, while solid lines represent negative electrical connections. In the present study, adult human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were dispersed within type I collagen hydrogel constructs, each one placed within individual cell culture chambers, mounted directly onto indium tin oxide-coated glass substrates, and exposed to a sinusoidal, 10-Hz alternating electric current of either 10 or 40 μA for six consecutive hours per day for up to 14 consecutive days.

The alternating electric current system consisted of five main components: (1) a function generator; (2) a multimeter; (3) an oscilloscope; (4) a 1000 Ω resistor; and (5) a cathode. A coaxial cable connected the positive output of the function generator to the positive end of a 1000 Ω resistor and the negative output of the function generator to the current-conducting cathode substrate. The top electrode (anode) was submerged in the supernatant medium and rested on the top of each solidified collagen hydrogel construct; the ITO–glass substrate served as the cathode. This arrangement assured that the alternating electric current (1) was delivered to the cells dispersed within each hydrogel construct contained in individual cell culture chambers; and (2) conduction through the closed circuit without delay and interference once the electric current was transmitted through the collagen hydrogels (Fig. 1). To monitor the signal output from the function generator, a second coaxial cable connected the positive output of the oscilloscope to the positive end of the resistor and the negative output from the oscilloscope to the current-conducting cathode substrate. A multimeter recorded readings of the alternating current as voltage difference across the 1000 Ω resistor.

Exposure of MSCs to alternating electric current

Adult human MSCs (initial seeding: 250,000 cells per hydrogel) dispersed within each collagen hydrogel construct were exposed to an alternating electric current regime chosen after optimization experiments (unpublished data). This regime consisted of the following parameters: (1) alternating electric current of either 10 or 40 μA; (2) 10 Hz frequency; (3) sinusoidal waveform; and (4) duration of exposure of 6 h per day for up to 14 consecutive days. No supplemental biochemicals (such as either dexamethasone or growth factors) were added to either the collagen hydrogel constructs or to the surrounding medium (MSC growth medium consisting of an MSC basal medium supplemented with serum, l-glutamine, and gentamicin/amphotericin-B) during these experiments. The medium surrounding each hydrogel was changed every 3 days throughout the duration of the experiments (up to 14 days). Controls were MSCs cultured dispersed within collagen hydrogel constructs under similar culture conditions and time periods, but not exposed to alternating electric current.

The viability of these MSCs was assessed after exposure to the aforementioned regime of alternating electrical current for 14 consecutive days using a commercially available LIVE/DEAD® viability assay (Invitrogen). The viability results of cells exposed to electric current was compared to those obtained from controls, that is, cells cultured dispersed within collagen hydrogel constructs under similar culture conditions, but not exposed to alternating electric current, for the same time period.

These experiments were run as single samples and repeated at four separate times.

Gene expression by MSCs in response to either BMPs or alternating electric current

At prescribed time points, collagenase (2 mg/mL) in phosphate-buffered saline was used to degrade each collagen hydrogel. MSC RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA using standard laboratory techniques.3 Specifically, TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), a reagent designed to isolate high-quality total RNA (as well as DNA and proteins) from cells, was used to isolate MSC RNA. This RNA was purified using the RNeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen) and converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using a commercially available reverse transcriptase kit (Finnzymes; Thermo Scientific) and protocols provided by the vendor. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of the cDNA products was performed using a DyNAmo SYBR green qPCR kit (Finnzymes) and the DNA Engine Opticon II continuous fluorescence detection system (Bio-Rad). Expression of early- (specifically, TAZ, Runx-2, and osterix) and late (specifically, osteopontin and osteocalcin) genes pertinent to osteodifferentiation (Table 1) of MSCs were monitored. Characteristic differentiation markers for the chondrocyte (type II collagen) and adipocyte (Fatty Acid Binding Protein-4) phenotypes were also monitored.

Table 1.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Primer Sequences for Select Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation Genes

| Protein | Sense primer | Anti-sense primer |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding Motif (TAZ) | 5′-GCA GAC ATC TGC TTC ACC AA-3′ | 5′-CAG GAT GAT GGG GTT GAG AT-3′ |

| Runx-2 | 5′-GCA GCT AGA AGG GAG TGG TG-3′ | 5′-AAG CCT TGC CAT ACA CCT TG-3′ |

| Osterix | 5′-GCC AGA AGC TGT GAA ACC TC-3′ | 5′-GCT GCA AGC TCT CCA TAA CC-3′ |

| Osteopontin | 5′-GCC GAG GTG ATA GTG TGG TT-3′ | 5′-GTG GGT TTC AGC ACT CTG GT-3′ |

| Osteocalcin | 5′-GAC TGT GAC GAG TTG GCT GA-3′ | 5′-GCC CAC AGA TTC CTC TTC TG-3′ |

| Fatty acid-binding protein-4 | 5′-TAC TGG GCC AGG AAT TTG AC-3′ | 5′-GTG GAA GTG ACG CCT TTC AT-3′ |

| Collagen II | 5′-CAG ACG GGT GAA CCT GGT AT-3′ | 5′-GAC CAT CTT GAC CTG GGA AA-3′ |

| Cyclophilin | 5′-CTC GAA TAA GTT TGA CTT GTG TTT-3′ | 5′-CTA GGC ATG GGA GGG AA-3′ |

These primer sequences were designed based on gene sequences obtained from the GenBank using Primer 3 software.

Relative gene expression (fold change) was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method4 as increase above the baseline, that is, MSCs cultured under standard cell culture conditions in the absence of either BMPs or alternating electric current and analyzed the day these MSCs were dispersed within the collagen hydrogel constructs. Cyclophilin was used as the housekeeping gene to ensure equal loading of RNA into all RT-PCR reactions. This housekeeping gene was selected, because it was the most stable gene across all conditions tested in the present studies (unpublished data). The results of gene expression by MSCs exposed to either alternating electric current or to the BMPs tested were compared to those obtained from respective controls, that is, cells cultured under similar conditions, but not exposed to either alternating electric current or BMPs for the same time period. Experiments were run as duplicates (using PCR triplicates each time) and repeated at three (for BMP studies) or four (for electric current studies) separate times.

Statistical analyses

All numerical data were reported as mean±standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed statistically according to standard analysis of variance and Tukey's test. Outliers of RT-PCR data acquired from MSC gene expression studies and reported as fold increase above baseline were determined using the modified Z-score analysis technique5; outlying data points (defined by a modified Z-score absolute value>3.5) were excluded from further analysis. Values of p<0.05 indicated a statistically significant level of difference between the means of the experimental and respective control groups.

Results

Electrical properties of the current-conducting collagen hydrogels

The average resistances (reciprocals of respective conductivities) of ITO-coated glass slides and of the 5 mg/mL collagen hydrogels measured 151 and 278 Ω, respectively. The lower resistance of the ITO-coated glass slides (on which the cell-containing collagen hydrogels attached during the alternating electric current experiments; Fig. 1) assured conduction through the closed circuit without delay and interference once the electric current was transmitted through the collagen hydrogels.

Validation of the osteogenic potential of MSCs

The differentiation potential of the commercially obtained adult human MSCs dispersed within type I collagen hydrogel constructs in the present study was validated by examining select gene expression pertinent to the established differentiation pathways (i.e., osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic) of these pluripotent cells after exposure to either BMP-2 or BMP-6 for 7 and 14 consecutive days using RT-PCR analysis.

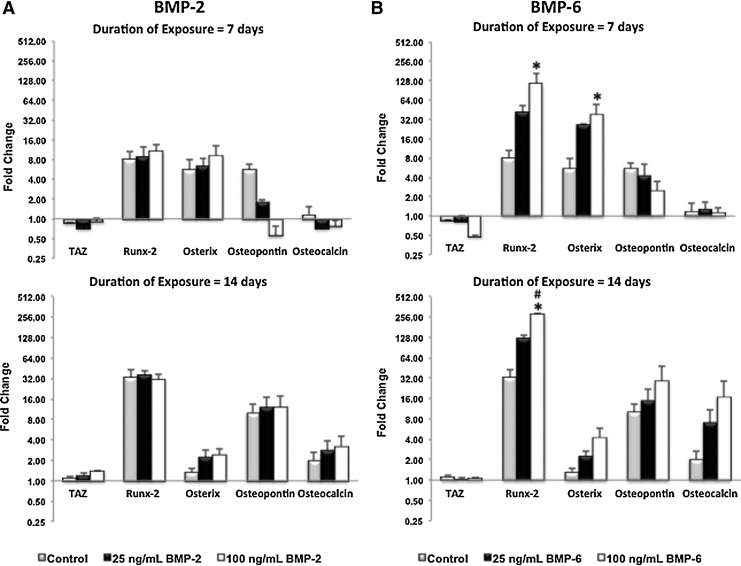

MSCs exposed to 25 and 100 ng/mL concentrations of BMP-2 for either 7 or 14 days expressed TAZ (a preosteocommitment gene), Runx-2, and osterix (preosteogenic genes), as well as osteopontin and osteocalcin (late-osteogenic markers) (Fig. 2A) at similar levels as the controls (i.e., MSCs cultured dispersed within type I collagen hydrogel constructs in the absence of BMP).

FIG. 2.

Time course of MSC differentiation as a function of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type (either BMP-2 or BMP-6) and concentration (either 25 or 100 ng/mL) of the respective BMPs. TAZ (a precommitment gene), Runx-2, and osterix (preosteogenic genes), as well as osteopontin and osteocalcin (late-osteogenic genes) were upregulated as a function of duration of exposure as well as of type and concentration of the bone morphogenetic proteins tested. Specifically, when exposed to 100 ng/mL of BMP-6 for 7 days, Runx-2 and osterix were significantly (p<0.05) upregulated as compared to controls, that is, MSCs cultured under similar conditions, but in the absence of BMP. When exposed to 100 ng/mL of BMP-6 for 14 consecutive days, Runx-2 was significantly (p<0.05) upregulated both as compared to controls and as compared to cells cultured in the presence of 25 ng/mL BMP-6 (B). In contrast, expression of the osteodifferentiation genes tested when MSCs were exposed to BMP-2 was similar to the results obtained from the respective controls (A). Data are values±standard error of the mean (n=3). *p<0.05 (analysis of variance [ANOVA] and Tukey's test; compared to results obtained from the respective controls). #p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; compared to results obtained in the presence of 25 ng/mL of the respective BMP tested).

In contrast, MSCs cultured in the presence of 100 ng/mL concentrations of BMP-6 exhibited significant (p<0.05) upregulation of the preosteogenic gene Runx-2 at day 7 and at day 14 (Fig. 2B). At that time, TAZ, Runx-2, osterix, and osteopontin gene expression was similar to that of controls. At day 14, significant (p<0.05) upregulation of the preosteogenic gene Runx-2 was observed in the presence of BMP-6 100 ng/mL when compared to results obtained both under respective controls and under exposure to BMP-6 25 ng/mL.

Genes of proteins pertinent to the adipogenic (specifically, Fatty Acid Binding Protein-4) and chondrogenic (specifically, type II collagen) phenotypes were not expressed by MSCs exposed to either type or concentration of the two BMPs for the duration of the experiments of the present study (data not shown).

MSC differentiation in response to alternating electric current

Adult human MSCs exposed to alternating electric current (either 10 or 40 μA) remained viable for the duration of the present study (data not shown).

Differentiation of adult human MSCs dispersed within type I collagen hydrogel constructs and exposed to a sinusoidal, 10 Hz, either 10 or 40 μA alternating electric current of 6 h per day for 7 and 14 consecutive days in the absence of biochemicals (such as dexamethasone and growth factors) was determined using RT-PCR analysis.

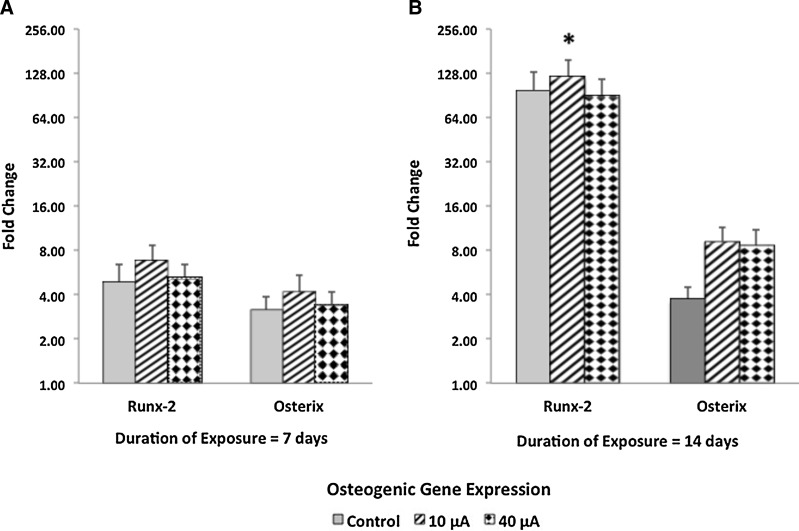

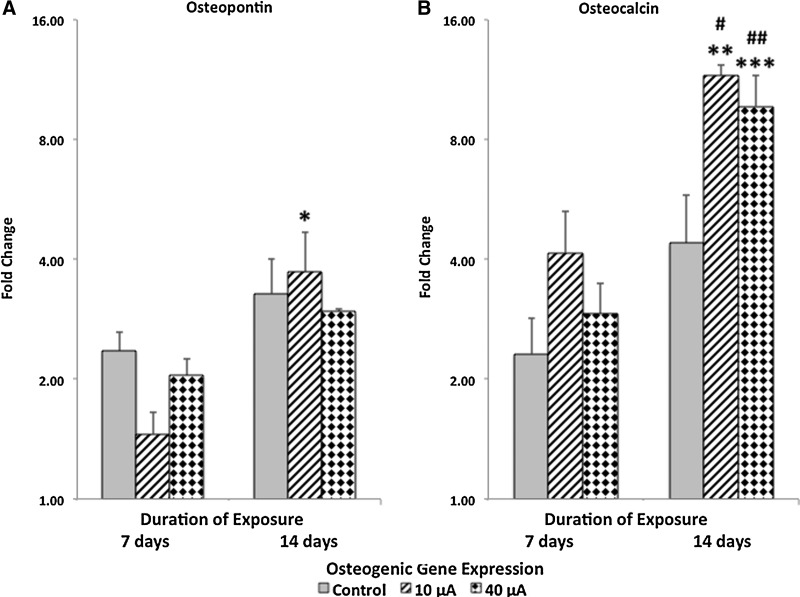

Compared to results obtained from controls (i.e., cells cultured dispersed within type I collagen hydrogel constructs in the absence of alternating electric current), exposure to 10 or 40 μA alternating electric current resulted in significantly (p<0.05) increased upregulation of osteocalcin (a late-osteogenic gene) at day 14, whereas expression for all other osteogenic genes tested (specifically, Runx-2 and osterix [Fig. 3] and osteopontin [Fig. 4]) was similar as compared to respective controls, that is, MSCs cultured under similar conditions for 7 and 14 days, but not exposed to alternating electric current.

FIG. 3.

Time course of preosteogenic genes expressed by adult human MSCs cultured within type I collagen hydrogel constructs and exposed to alternating electric current for 6 h daily. Compared to results obtained when MSCs were maintained under control conditions, Runx-2, a preosteogenic gene, was significantly (p<0.05) upregulated as a function of duration [14 versus 7 days, (B) and (A), respectively] of exposure to 10-μA alternating electric current. Data are values±standard error of the mean (n=4); *p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; Runx-2 expression at day 14 as compared to Runx-2 expression at day 7 in the presence of 10-μA electric current).

FIG. 4.

Time course of late-osteogenic genes expressed by adult human MSCs cultured within type I collagen hydrogel constructs and exposed to alternating electric current. Osteopontin, a late-osteogenic gene, was significantly (p<0.05) upregulated as a function of duration (14 versus 7 days) of exposure to 10-μA alternating electric current (A). Compared to respective controls, osteocalcin was significantly (p<0.05) upregulated after the MSCs were exposed to either 10 μA (striped bars) or 40 μA (dotted bars) of alternating electric current for 14 days (B). Controls were MSCs cultured under similar conditions and time periods, but not exposed to alternating electric current. Osteocalcin was also significantly upregulated (p<0.05) as a function of duration (14 vs. 7 days) when exposed to either 10 μA or 40 μA (B). Data are values±standard error of the mean (n=4). #p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; osteocalcin results obtained under 10 μA compared to results obtained under from the respective control at day 14). ##p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; osteocalcin results obtained under 40 μA compared to results obtained under from the respective control at day 14). *p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; osteopontin results at day 14 versus day 7 under 10 μA). **p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; osteocalcin results at day 14 versus day 7 under 10 μA). ***p<0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey's test; osteocalcin results at day 14 versus day 7 under 40 μA).

When comparing the expression of osteogenic genes by MSCs exposed to 10 μA alternating electric current as a function of time, the expression of Runx-2 (a preosteogenic gene; Fig. 3) and osteopontin and osteocalcin (both late-osteogenic genes; Fig. 4) was significantly (p<0.05) increased at day 14 as compared to results obtained at day 7. Exposure of MSCs to 40 μA of alternating electric current resulted in a significant (p<0.05) increase in the expression of osteocalcin (Fig. 4B) at day 14 as compared to results obtained at day 7. In contrast, Runx-2, osterix, osteopontin, and osteocalcin gene expression by MSCs cultured under control conditions for both 7 and 14 consecutive days did not increase as a function of time.

Most importantly, MSCs exposed to the alternating electric current levels tested for 7 and 14 consecutive days in the absence of biochemical compounds, such as dexamethasone and growth factors, did not express genes characteristic of either the adipogenic (specifically, Fatty Acid Binding Protein-4) or the chondrogenic (specifically, type II collagen) phenotypes (data not shown).

Discussion

Interest in the use of electric current for bone repair and regeneration was triggered by the discovery of piezoelectric effects in bone.6 Various in vivo animal studies followed in attempts to heal bone fractures under electrical stimulation. For example, when direct currents (ranging from 1 to 20 μA) were continuously applied to osteotomies for up to 3 weeks, increased new bone formation was reported in rabbit models.7–10 Direct comparisons of these results, however, are not possible because of differences in species (i.e., canine,11 turkey,12 and rabbit7), type of current (i.e., direct,13 electromagnetic,14 and pulsed12), and in the type of the bone defect (i.e., fractures14 and osteotomies10). Despite the aforementioned differences that preclude definitive universal conclusions, there is agreement among the studies reported in the literature that electrical stimulation promotes bone healing and/or bone tissue regeneration, especially in the case of healing bone fractures. However, the underlying cellular- and molecular-level mechanisms pertinent to the formation of new bone remain, at best, partially understood.

Advances in the fields of cellular and molecular biology made possible several subsequent in vitro studies investigating the effect of alternating electric current on bone cell functions. The bone cells involved in the process of new bone formation include (1) osteoblasts, the bone-forming cells; and (2) MSCs, pluripotent, and bone marrow cells with the potential to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes upon appropriate stimulation. These in vitro studies established that exposure of rat calvarial osteoblasts (cultured in a medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, but not exogenous growth factors on flat, electrically conductive substrates) to 10 μA of alternating electric current for 6 h daily promoted cell functions pertinent to new bone formation.2 Specifically, osteoblast proliferation (after 2 consecutive days of exposure), gene expression of various extracellular matrix proteins, specifically collagenous (i.e., collagen I after both 6 h and 21 consecutive days of exposure) and noncollagenous (i.e., osteonectin, osteoprotegerin, and osteocalcin after 21 consecutive days of exposure), as well as calcium deposition in the osteoblast extracellular matrix (after 21 consecutive days of exposure) were all enhanced upon exposure to the aforementioned alternating electric current regime tested.2 Another study cultured adult human MSCs on flat substrates in an osteogenic medium (containing dexamethasone [1000 nM] and BMP-2 [100 ng/mL], two osteogenic mitogens known to induce the differentiation of MSCs to osteoblasts15) and exposed these cells to 100 μA alternating electric current for 40 min daily.16 Under those conditions, the MSCs displayed increased gene expression of collagen I and alkaline phosphatase activity after 15 and 20 consecutive days of exposure to alternating electric current compared to the respective controls, that is, MSCs cultured under similar conditions in the aforementioned osteogenic growth-factor-containing medium, but not exposed to alternating electric current.16 Molecular mechanisms underlying this MSC osteodifferentiation in response to alternating electric current were not addressed.16

Intrigued by the potential of this biophysical stimulus and motivated by the need to further elucidate the cellular and molecular level functions underlying bone healing, the present study assembled, calibrated, and used a custom laboratory system to expose adult human MSCs, dispersed within three-dimensional, type I collagen hydrogels to alternating electric current. Alternating current was chosen because (1) use of this type of current eliminated problems arising from the formation of a dielectric cell, and subsequent protein buildup at the respective electrodes observed when direct electric current was used in other studies8; and (2) literature reports of in vitro studies provided evidence that alternating electric current enhanced rat calvarial osteoblast functions pertinent to new bone formation.2 Additional care was taken to validate the differentiation potential of the adult human MSCs before these cells were used in the present study of the effect of alternating electric current. These findings, which are in agreement with those reported in the literature,17 established a reference for the differentiation pattern to which the results obtained when the MSCs were exposed to the alternating electric current (a biophysical stimulus) alone (i.e., in the absence of supplemented, exogenous, biochemical compounds) were compared.

The present study not only confirmed literature reports17 that exposure to BMP-2 and/or BMP-6 induces MSC osteodifferentiation, but also was the first to provide evidence that this differentiation was a function of three important parameters (Fig. 2): specifically, adult human MSC osteodifferentiation was affected by (1) the type (BMP-6 and BMP-2), (2) the duration of exposure (7 and 14 days) to the respective growth factors, and (3) the concentration (25 and 100 ng/mL) of the respective growth factors.

What unequivocally distinguishes the present study from previous reports in the literature, however, is that exposure of adult human MSCs to alternating electric current alone (i.e., in the absence of supplemented biochemicals such as dexamethasone and growth factors) promoted and accelerated specific differentiation of these stem cells to the osteogenic phenotype (Fig. 4), but neither to the adipogenic nor chondrogenic phenotypes. Osteodifferentiation under the electric current conditions tested resulted in an earlier increase in the expression of genes indicative of early (Fig. 3) and late (Fig. 4) stages of the time course in the osteogenic differentiation pathway.18 Moreover, exposure to the chosen biophysical stimulus promoted and accelerated the osteogenic differentiation process as a function of the current level and duration of exposure to alternating electric current.

The approach tested in the present study is a potentially scalable one and presents a valuable (but yet untapped) resource for the production of osteoblasts for various bone-related tissue-engineering and tissue regeneration applications. Differentiation of adult human MSCs into cells of a specific and desirable phenotype under the conditions established in the present study can provide critically needed cell supplies for cell-based assays and/or therapies needed for regenerating and repairing damaged tissues.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Marissa Wechsler, Ms. Vanessa Wechsler, Dr. John McCarrey, Dr. Rishein Gupta, Dr. Ashlesh Murthy, Dr. Eric da Wall, Ms. Amber Baer, and Mr. Stephen Chen for helpful discussions and assistance with various aspects of the project.

This study was supported in part by the Texas Advanced Research Program (under Grant No. 010115-0074-2007), as well as by funds from the Peter T. Flawn Professorship and from New UTSA Faculty funds (to RB). CMC thanks the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) for a Presidential Dissertation Scholarship, the UTSA College of Engineering for Valero Research Excellence Funds and a Valero Travel Award, as well as the UTSA Department of Biomedical Engineering for a graduate student fellowship.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ulmann K. The effects of alternating current stimulation on select osteoblast functions [M.S. Thesis] Department of Biomedical Engineering, Renesselaer Polytechnic Institute; Troy, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Supronowicz P.R. Ajayan P.M. Ullmann K.R. Arulanandam B.P. Metzger D.W. Bizios R. Novel current-conducting composite substrates for exposing osteoblasts to alternating current stimulation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:499. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creecy C.M. A strategy to optimize mesenchymal stem cell differentiation for bone tissue engineering [Ph.D. Dissertation] Department of Biomedical Engineering, The University of Texas at San Antonio; San Antonio, TX: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livak K.J. Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iglewiczm B. Hoaglin D. The ASQC basic references in quality control: statistical techniques. In: Edward F., editor; Mykytka , editor. How to Detect and Handle Outliers. Vol. 16. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press; 1993. pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukada E. Yasuda I. On the piezoelectric effect of bone. J Physiol Sci Japan. 1957;12:1158. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedenberg Z.B. Andrews E.T. Smolenski B.I. Pearl B.W. Brighton C.T. Bone reactions to varying amounts of direct current. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1970;131:894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black J. Baranowski T.J., Jr. Brighton C.T. Electrochemical aspects of d.c. stimulation of osteogenesis. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 1984;12:323. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yonemori K. Matsunaga S. Ishidou Y. Maeda S. Yoshida H. Early effects of electrical stimulation on osteogenesis. Bone. 1996;19:173. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagiwara T. Bell W.H. Effect of electrical stimulation on mandibular distraction osteogenesis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:12. doi: 10.1054/jcms.1999.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassett C.A.L. Pawluk R.J. Becker R.O. Effects of electric current on bone in vivo. Nature. 1964;204:652. doi: 10.1038/204652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLeod K.T. Rubin C.T. The effect of low-frequency electrical fields on osteogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozic K.J. Glazer P.A. Zurakowski D. Simon B.J. Lipson S.J. Hayes W.C. In vivo evaluation of coralline hydroxyapatite and direct current electrical stimulation in lumbar spinal fusion. Spine. 1999;24:2127. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassett C.A.L. Pawluk R.J. Pilla A.A. Acceleration of fracture repair by electromagnetic fields: A surgically non-invasive method. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;238:242. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb26794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain G. Fox J. Ashton B. Middleton J. Stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hronik-Tupaj M. Rice W.L. Cronin-Golomb M. Kaplan D.L. Georgakoudi I. Osteoblastic differentiation and stress response of human mesenchymal stem cells exposed to alternating current electric fields. Biomed Eng Online. 2011;10 doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman M.S. Long M.W. Hankenson K.D. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by bone morphogenetic protein-6. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:538. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes F.J. Turner W. Belibasakis G. Martuscelli G. Effects of growth factors and cytokines on osteoblast differentiation. Periodontology 2000. 2006;41:48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]