Abstract

The carbon isotope ratio (δ13C) is elevated in corn- and cane sugar-based foods and has recently shown associations with sweetener intake in multiple U.S. populations. However, a high carbon isotope ratio is not specific to corn- and sugar cane-based sweeteners, as other foods, including meats and fish, also have elevated δ13C. This study examines whether the inclusion of a second marker, the nitrogen isotope ratio (δ15N), can control for confounding dietary effects on δ13C and improve the validity of isotopic markers of sweetener intake. The study participants are from the Yup’ik population of southwest Alaska and consume large and variable amounts of fish and marine mammals known to have elevated carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios. Sixty-eight participants completed 4 weekly 24-h recalls followed by a blood draw. RBC δ13C and δ15N were used to predict sweetener intake, including total sugars, added sugars, and sugar-sweetened beverages. A model including both δ13C and δ15N explained more than 3 times as much of the variation in sweetener intake than did a model using only δ13C. Because carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios are simultaneously determined in a single, high-throughput analysis, this dual isotope marker provides a simple method to improve the validity of stable isotope markers of sweetener intake with no additional cost. We anticipate that this multi-isotope approach will have utility in any population where a stable isotope biomarker is elevated in several food groups and there are appropriate “covariate” isotopes to control for intake of foods not of research interest.

Introduction

There is growing consensus that alternatives to self-reported food intake based on objective biomarkers are needed to more validly study associations of diet and chronic disease risk (1–3). Although most dietary biomarkers are based on concentrations of micronutrients in blood or other tissues (4), we and others have shown that naturally occurring variations in stable isotope ratios can also be used as objective measures of diet (5–9). We are developing stable isotope biomarkers to study associations of diet with chronic disease risk in the Yup’ik population of southwest Alaska. Our previous work with this population has focused on the nitrogen isotope ratio (δ15N) as an indicator of traditional marine food intake (8, 10); however, we have also shown associations between the carbon isotope ratio (δ13C) and intake of nontraditional (market) foods (7). Here, we consider whether isotope ratios can be used to indicate intake of sweeteners in this population.

Previous studies in other U.S. populations have shown positive associations of the carbon isotope ratio with reported sweetener intake (6, 9) because of the elevated δ13C values of corn- and cane sugar-based sweeteners (11). However, the carbon isotope marker is not specific to sweetener intake, because δ13C values are also elevated in other foods. For example, commercial meat products have elevated δ13C values, because livestock in the U.S. agricultural system are commonly raised on corn-based feed (12, 13). Furthermore, foods deriving from the marine environment have elevated δ13C values, because oceanic bicarbonate, the source of carbon to marine foodwebs, is enriched in 13C relative to atmospheric CO2 (14, 15). In the Yup’ik population, fish and marine mammals are an important contributor to the traditional diet (16) and one of the primary contributors of elevated 13C (7). Intake of traditional marine foods can be measured using δ15N (8), because fish and marine mammals also have elevated δ15N values (7). Therefore, we hypothesize that the validity of the carbon isotope biomarker of sweetener intake will be increased by using a multivariable model that controls for marine food intake using δ15N. Here, we tested this hypothesis in a community-based sample of 68 Yup’ik people that completed 4 weekly 24-h recalls (24HR) followed by a blood draw. Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios are simultaneously determined from a single sample; therefore, this method could provide a simple and inexpensive improvement to isotopic biomarkers of sweetener intake.

Participants and Methods

Participant recruitment and procedures.

Data are from the Center for Alaska Native Health Research Negem Nallunailkutaa (“Foods’ Marker”) study. This study was approved by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Institutional Review Board and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation Human Studies Committee.

Between 2008 and 2009, a community-based sample of 68 participants aged 14–79 y was recruited from 2 coastal communities in southwest Alaska. At entry into the study, participants completed a demographic questionnaire and the first of 4 24HR dietary interviews. Three more dietary interviews were conducted over the next 4 wk. Biological samples were collected at least 2 wk after the completion of the final dietary interview, so that the average age of RBC would match the period during which dietary interviews were conducted (17–19).

Assessment of dietary intake.

24HRs were collected from each participant by certified interviewers using algorithm-driven, computer-assisted software [Nutrition Data System for Research software 2008; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN]. The majority of interviews were completed in person (93%, n = 261); some participants completed either 1 (n = 15) or 2 (n = 2) interviews over the telephone. Participants were asked to recall all food and beverages consumed the day prior to the interview using a multiple pass approach. For accuracy, all participants were given portion estimation tools (measuring cups, rulers, and food models or portion estimation guides; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). Although most participants were bilingual, a native Yup’ik speaker conducted interviews for participants who did not speak English. Dietary interviews were, on average, 9 ± 5 d apart, with a minimum of 2 d between recalls. Most participants (93%) had 3 weekday recalls and 1 weekend recall. No recalls were excluded due to unreasonable intake (20).

The Nutrition Data System for Research Food and Nutrient Database (21) was used to calculate food and nutrient intake. In this study, sweetener intake is measured in 3 ways: as total sugars, added sugars, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB). Total sugar intake (g/d) is defined as the total sum of all mono- and disaccharides consumed and includes primarily fructose, glucose, and sucrose. Added sugars (g/d) were calculated as the sum of sugars and syrups added to foods during food preparation or commercial food processing. SSB intake was calculated as the sum of servings of sweetened soft drinks and sweetened fruit drinks [servings/d, 8 fl oz (237 mL)/serving].

We also give data on the intake of other food items that have elevated δ13C values, including commercial meats (percent energy), fish and marine mammals (percent energy), and corn products (g/d). Commercial meats were those purchased from local grocery stores and were distinct from intake of traditional meats and fish and marine mammals. We use these terms to specifically refer to traditional foods harvested from the local environment. Consumption of market-purchased fish (i.e., tuna) was minimal: among the 9 participants reporting market fish, consumption was on average 36 ± 35 kcal/d. Corn products included whole corn and other foods made from whole corn, including popcorn, corn chips, and corn tortillas.

Stable isotope analysis.

RBC from fasted blood samples were pipetted into tin capsules, autoclaved, and prepared for isotopic analysis as previously described (7). Neither autoclaving nor the use of EDTA tubes affects RBC carbon or nitrogen isotope ratios (22). Samples were analyzed at the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility by continuous-flow isotope ratio MS, using a Costech ECS4010 Elemental Analyzer (Costech Scientific) interfaced to a Finnigan Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer via the Conflo III interface (Thermo-Finnigan). The conventional means of expressing natural abundance isotope ratios is as δ values in permil (‰) relative to international standards as δX = (Rsample – Rstandard)/(Rstandard) · 1000‰ (23). Here, R is the ratio of heavy:light isotope (15N:14N or 13C:12C). The standards are Vienna PeeDee Belemnite for carbon and atmospheric nitrogen for nitrogen. To assess analytical precision, an internal working standard was analyzed for every 10 samples; precision was measured as the SD of these analyses (0.2‰). Because biological samples from this study have a lower 13C:12C than Vienna PeeDee Belemnite, δ13C values are negative. δ13C values are hereafter abbreviated as δ13C and δ15N values are abbreviated δ15N.

Statistical analyses.

The following dietary intake variables were log-transformed for analyses: total sugars (g/d), added sugars (g/d), SSBs (servings/d+1), and corn products (g/d+1). Because of known relations between age and dietary patterns (7, 24), we tested whether sex, BMI, and dietary intakes of sweeteners, fish and marine mammals, commercial meats, and corn products differed by age, using 1-way ANOVA. We examined whether foods with elevated isotope ratios were independently associated with RBC δ13C and δ15N using multiple regression models where the isotope ratios were the dependent variables. We report both standardized and unstandardized β-coefficients for these models. To test whether a model using both δ13C and δ15N was a better predictor of sweetener intake than a model using only δ13C, we used linear regression models. Because the dietary-dependent variables were log-transformed for analyses, the β-coefficients of these models were back-transformed for ease of interpretation; these are interpreted as proportional change in the dietary variable for every 1‰ change in isotope ratio. Means are presented ± SD and significance was set at 2-sided α = 0.05. Statistical tests were performed using JMP version 8 (SAS Institute).

Results

Table 1 gives distributions of sex and means of BMI, isotope ratios, and dietary intake measures by age. The study sample ranged in age from 14 to 79 y (mean = 40 ± 18 y) and was evenly divided between men and women. BMI and diet substantially differed by age. Mean BMI and intake of fish and marine mammals, protein, and fat increased with age. Intake of total sugar, added sugars, SSBs, commercial meats, and carbohydrates decreased with age. There was no association of age with intake of corn products. There was a positive association of δ15N with age, but no association of age with δ13C. There was no association between RBC δ13C and δ15N (r = 0.12; P = 0.35).

TABLE 1.

Associations of sex, BMI, and measures of dietary intake with age1

| Age (y) |

||||||

| Total | <20 | 20 –<40 | 40 –<60 | ≥60 | P-trend | |

| n | 68 | 11 | 22 | 27 | 8 | |

| Sex, % female | 50 | 45 | 54 | 52 | 38 | 0.95 |

| BMI, 2 | 27.1 ± 6.4 | 23.0 ± 2.5 | 25.4 ± 5.6 | 29.2 ± 6.2 | 31.4 ± 9.4 | 0.0045 |

| δ13C, ‰ | −19.8 ± 0.6 | −19.9 ± 0.7 | −19.7 ± 0.7 | −19.8 ± 0.5 | −20.0 ± 0.5 | 0.52 |

| δ15N, ‰ | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 9.8 ± 1.4 | 12.3 ± 0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Macronutrient intake | ||||||

| Carbohydrate, % energy | 44 ± 14 | 54 ± 6 | 53 ± 10 | 40 ± 10 | 22 ± 6 | <0.0001 |

| Protein, % energy | 18 ± 6 | 14 ± 3 | 15 ± 4 | 21 ± 6 | 25 ± 5 | <0.0001 |

| Fat, % energy | 38 ± 9 | 33 ± 5 | 33 ± 7 | 40 ± 7 | 52 ± 6 | <0.0001 |

| Sweetener intake | ||||||

| Total sugar, g/d | 89 | 136 | 120 | 76 | 36 | <0.0001 |

| (76, 103) | (109, 171) | (100, 145) | (61, 95) | (22, 58) | ||

| Added sugar, g/d | 74 | 115 | 104 | 60 | 30 | <0.0001 |

| (62, 88) | (87, 151) | (86, 125) | (46, 80) | (18, 51) | ||

| SSB, servings/d | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| (1.1, 1.8) | (1.4, 3.4) | (1.6, 2.9) | (0.7, 1.4) | (0.0, 0.6) | ||

| Other foods with elevated δ13C | ||||||

| Corn products, g/d | 11 | 28 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 0.50 |

| (8, 16) | (17, 45) | (7, 21) | (5, 16) | (2, 10) | ||

| Commercial meats, % energy | 11 ± 8 | 13 ± 5 | 11 ± 7 | 12 ± 8 | 3 ± 3 | 0.0126 |

| Fish and marine mammals, % energy | 18 ± 18 | 5 ± 9 | 10 ± 12 | 21 ± 16 | 46 ± 13 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, or as geometric means (95% CI) for log-transformed variables. SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Table 2 gives associations of δ13C and δ15N with foods that are known to have elevated isotope ratios. RBC δ13C was independently associated with total sugar, fish and marine mammals, and commercial meat intake. RBC δ13C was not associated with intake of corn products, which was low in this population. There were similar results when total sugar was replaced with either added sugars or SSB in the model. RBC δ15N was strongly associated with intake of fish and marine mammals but not commercial meats.

TABLE 2.

| Stable isotope ratio | Dietary variable | βs | β (95% CI) | R2 |

| δ13C, ‰ | Total sugar, g/d | 0.36** | 0.35 (0.09, 0.61) | 0.26 |

| Fish and marine mammals, % energy | 0.46** | 1.54 (0.52, 2.57) | ||

| Commercial meats, % energy | 0.49** | 3.94 (1.80, 6.09) | ||

| Corn products, g/d | 0.07 | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.15) | ||

| δ15N, ‰ | Fish and marine mammals, % energy | 0.72*** | 7.24 (5.13, 9.35) | 0.50 |

| Commercial meats, % energy | 0.02 | 0.49 (−4.55, 5.54) |

In these models, δ15N and δ13C were the dependent variables and dietary intake measures the independent variables. Significance of association: *** < 0.0001; **P < 0.01.

Both standardized (βs) and unstandardized (β) β-coefficients are presented.

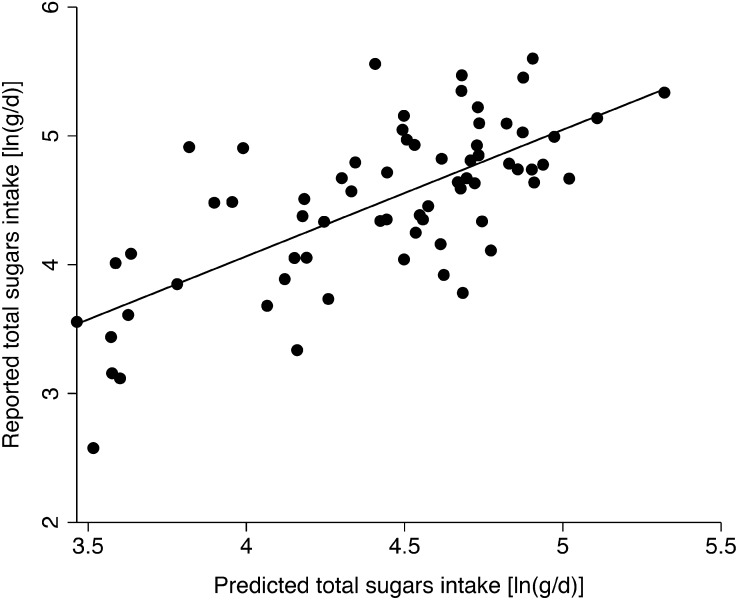

Table 3 compares 2 models to predict total sugar, added sugar, and SSB intake. The first model is based on δ13C alone, as has been proposed elsewhere (6, 9). The second model is based upon δ13C and δ15N to account for the contribution of elevated δ13C from fish and marine mammal intake. For all models predicting sweetener intake based on δ13C, the amount of variance explained and the β-coefficient for δ13C markedly increased with the addition of δ15N as a covariate. The effect of adding δ15N was most striking for the model to predict total sugar intake, in which the amount of variance explained by the model (R2) increased from 6 to 48% and the β-coefficient increased from 28 to 39% change in total sugar intake (g/d) per 1‰ change in the carbon isotope ratio. Figure 1 shows the relationship between reported total sugar intake and the predicted values from a regression model using both δ13C and δ15N.

TABLE 3.

Multiple regression analyses comparing prediction of dietary sweetener intake from individual and combined isotopic measures12

| Total sugar (g/d) |

Added sugar (g/d) |

SSB (servings/d) |

||||||||

| Model | Isotope ratio, ‰ | β | 95% CI | R2 | β | 95% CI | R2 | β | 95% CI | R2 |

| 1 | δ13C | 0.25* | 0.00, 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.20 | −0.08, 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.21* | 0.00, 0.42 | 0.05 |

| 2 | δ13C | 0.33** | 0.14, 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.28* | 0.04, 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.26** | 0.08, 0.44 | 0.31 |

| δ15N | −0.23*** | −0.29, -0.16 | −0.21*** | −0.29, -0.14 | −0.15*** | −0.21, -0.09 | ||||

In these models, δ15N and δ13C were the independent variables and measures of sweetener intake the dependent variables. Significance of association: *** < 0.0001; ** P < 0.01; * P < 0.05. SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Slopes have been back-transformed for ease of interpretation and are interpreted as proportional change in sweetener intake for every 1‰ change in isotope ratio.

FIGURE 1.

Associations between reported total sugar intake and predicted total sugar intake. Total sugar intake was predicted using the formula ln(predicted total sugars) = 13.1 + 0.33(δ13C) − 0.23(δ15N). This formula was generated based on a model of reported sugar intake using δ13C and δ15N as predictors (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated a new approach for using isotope ratios to assess intake of corn- and cane sugar-based sweeteners in a Yup’ik study population. It expanded upon a previously proposed method based on δ13C alone (5, 6, 9, 11), which is subject to confounding due to the elevated δ13C of foods other than sweeteners. By using δ15N as a covariate to control for fish and marine mammal intake, the variability in sweetener intake explained by this marker substantially increased to a maximum of 48% for total sugars. This improvement likely has 2 causes in this Yup’ik study population: first, by factoring out the significant effect of high fish and marine mammal intakes on δ13C, and second, because of a strong, age-related diet pattern in this population, in which intakes of fish and marine mammals and sweeteners are negatively correlated. However, because δ15N was not associated with commercial meat intake in this study population, this adjustment is unable to account for the effect of commercial meat intake on δ13C. These results support the use of a dual isotope model using both δ13C and δ15N as a valid measure of sweetener intake in the Yup’ik population and suggest a candidate marker of sweetener intake based on both δ13C and δ15N for further evaluation in the general U.S. population.

The dual isotope model of sweetener intake presented in this study is an example of a more generalizable approach to using isotopic signatures as dietary biomarkers. Where a stable isotope biomarker is elevated in several food groups, it may be possible to use one or more different “covariate” isotopes to control for intake of foods not of research interest. These multiple isotope models can then be used to generate a predictive equation for estimating dietary intake. However, these equations will require calibration in each target population, because both the isotopic ecology of the diet and the underlying dietary patterns driving tissue isotope ratios will differ by population. For example, in the Yup’ik population, δ15N is associated with intake of fish and marine mammals but not commercial meats, because fish and marine mammals have higher δ15N than commercial meats and their intakes are negatively associated. In populations that consume relatively little fish, δ15N is positively associated with meat intake (25, 26), because meats have elevated δ15N relative to other commercial foods (27, 28). Thus, in the general U.S. population, we anticipate that δ15N will improve δ13C-based biomarkers of sweetener intake by controlling for the significant effect of commercial meat intake on tissue δ13C (9). Testing this hypothesis to validate the dual isotope biomarker of sweetener intake will be the next step in the development of stable isotope biomarkers in the general U.S. population.

The existing predictive biomarkers of sweetener intake, 24-h urinary sugars, provide valid and reliable measures of absolute sweetener intake (29); however, the isotopic biomarkers presented in this study have several practical advantages over these measures. Stable isotope ratios can be inexpensively measured in many biological samples, including RBC (7, 8), serum (9, 30), hair (10, 31), nails (31, 32), and urine (33). These tissues incorporate dietary information over the period of time when they were synthesized; therefore, stable isotope ratios can be informative about intake over the past several weeks or months, depending on the tissue analyzed. In contrast, because 24-h urinary measurements reflect only a single day’s intake, several collections are required to estimate usual intake, which carries substantial participant burden (4). Validation studies that compare the performance of our proposed biomarker with these predictive markers in a controlled setting are warranted to determine the relative validity of these measures.

The primary limitation of this study is that we evaluated the performance of our proposed biomarkers against self-reported intakes, which are known to be subject to substantial error. Although little is known about factors that may bias dietary self-report in the Yup’ik population, the primary factors identified in other populations are sex and obesity (34, 35). Neither sex nor BMI was associated with δ13C in this study; therefore, these biases could not explain our results. One limitation of the δ13C biomarker more generally is that it is not associated with intake of sweeteners that are not 13C enriched, such as beet sugar, honey, and intrinsic sugars found in fruit and dairy products (11). In the Yup’ik population, intake of these sugars is low (24); therefore, we demonstrate similar associations of δ13C with total and added sugars. In the general U.S. population, the intake of sugars that are not 13C enriched is higher; for this reason, we anticipate that associations of δ13C values with total sugar intake will be attenuated, as has been shown for serum δ13C (9). Furthermore, in Europe, where sweeteners are based primarily on beet sugar, isotopic markers will not indicate sweetener use.

In summary, this study evaluated a model for estimating sweetener intake based on RBC δ13C and δ15N in a Yup’ik study population. This approach requires evaluation in other U.S. populations, but we expect its validity to be similar or improved in populations with lower fish intake. In addition, controlled feeding studies are needed to further validate this biomarker and calibrate how changes in sweetener intake modify isotopic ratios. This combined isotopic biomarker will increase our ability to discern the role played by sweetener intake in the development of chronic disease and to monitor the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce their consumption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eliza Orr, Jynene Black, and Kristine Niles at the Center for Alaska Native Health Research for fieldwork assistance. They also thank Tim Howe and Norma Haubenstock at the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility for their assistance with isotope analysis. This manuscript was improved by comments from Dr. Trixie Lee, Dr. Caroline van Hemert, and Dr. Kyungcheol Choy. D.M.O. designed research; S.H.N., D.M.O., S.E.H., A.B., and B.B.B. conducted research; S.H.N. analyzed data; S.H.N., D.M.O., and A.R.K. wrote the manuscript; and S.H.N. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1.Bingham SA. Biomarkers in nutritional epidemiology. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:821–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhnle GG. Nutritional biomarkers for objective dietary assessment. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:1145–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Tasevska N, Potischman N. Can we use biomarkers in combination with self-reports to strengthen the analysis of nutritional epidemiologic studies? Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2010;7:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenab M, Slimani N, Bictash M, Ferrari P, Bingham SA. Biomarkers in nutritional epidemiology: applications, needs and new horizons. Hum Genet. 2009;125:507–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook CM, Alvig A, Liu Y, Schoeller D. The natural 13C abundance of plasma glucose is a useful biomarker of recent dietary caloric sweetener intake. J Nutr. 2010;140:333–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davy BM, Jahren AH, Hedrick VE, Comber DL. Association of delta(13)C in Fingerstick blood with added-sugar and sugar-sweetened beverage intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:874–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nash SH, Bersamin A, Kristal AR, Hopkins SE, Church RS, Pasker RL, Luick BR, Mohatt GV, Boyer BB, O'Brien DM. Stable nitrogen and carbon isotope ratios indicate traditional and market food intake in an indigenous circumpolar population. J Nutr. 2012;142:84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Brien DM, Kristal AR, Jeannet MA, Wilkinson MJ, Bersamin A, Luick B. Red blood cell 15N: a novel biomarker of dietary eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:913–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung EH, Saudek C, Jahren A, Kao W, Islas M, Kraft R, Coresh J, Anderson C. Evaluation of a novel isotope biomarker for dietary consumption of sweets. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1045–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nash SH, Kristal AR, Boyer BB, King IB, Metzgar JS, O'Brien DM. Relation between stable isotope ratios in human red blood cells and hair: implications for using the nitrogen isotope ratio of hair as a biomarker of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1642–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahren AH, Saudek C, Yeung E, Kao W, Kraft R, Caballero B. An isotopic method for quantifying sweeteners derived from corn and sugar cane. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1380–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesson LA, Podlesak D, Thompson A, Cerling T, Ehleringer J. Variation of hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen stable isotope ratios in an American diet: fast food meals. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:4084–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahren AH, Kraft R. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in fast food: signatures of corn and confinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17855–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chisholm BS, Nelson DE, Schwarcz HP. Stable-carbon isotope ratios as a measure of marine versus terrestrial protein in ancient diets. Science. 1982;216:1131–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutton TW. Stable carbon isotope ratios of natural material: II. Atmospheric, terrestrial, marine and freshwater environments. : Coleman DC, Fry B, editors. Carbon isotope techniques. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersamin A, Zidenberg-Cherr S, Stern J, Luick B. Nutrient intakes are associated with adherence to a traditional diet among Yup'ik Eskimos living in remote Alaska Native communities: The CANHR study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berlin NI, Waldmann T, Weissman S. Life span of red blood cell. Physiol Rev. 1959;39:577–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen RM, Franco R, Khera P, Smith E, Lindsell C, Ciraolo P, Palascak M, Joiner C. Red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c. Blood. 2008;112:4284–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eadie GS, Brown I. The potential life span and ultimate survival of fresh red blood cells in normal healthy recipients as studied by simultaneous Cr51 tagging and differential hemolysis. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:629–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig MR, Kristal AR, Cheney CL, Shattuck AL. The prevalence and impact of ‘atypical’ days in 4-day food records. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:421–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schakel SF. Maintaining a nutrient database in a changing marketplace: keeping pace with changing food products: a research perspective. J Food Compost Anal. 2001;14:315–22 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkinson MJ, Yai Y, O'Brien D. Age-related variation in red blood cell stable isotope ratios (delta13C and delta15N) from two Yupik villages in southwest Alaska: a pilot study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fry B. Stable isotope ecology. New York: Springer; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bersamin A, Luick B, Ruppert E, Stern J, Zidenberg-Cherr S. Diet quality among Yup'ik Eskimos living in rural communities is low: The Center for Alaska Native Health Research pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1055–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petzke KJ, Boeing H, Klaus S, Metges C. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopic composition of hair protein and amino acids can be used as biomarkers for animal-derived dietary protein intake in humans. J Nutr. 2005;135:1515–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connell TC, Hedges R. Investigations into the effect of diet on modern human hair isotopic values. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;108:409–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minagawa M, Wada E. Stepwise enrichment of N15 along food chains: further evidence and the relation between delta N15 and animal age. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48:1135–40 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoeller D, Minagawa M, Slater R, Kaplan I. Stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen in the contemporary North-American human food web. Ecol Food Nutr. 1986;18:159–70 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tasevska N, Runswick SA, McTaggart A, Bingham SA. Urinary sucrose and fructose as biomarkers for sugar consumption. Cancer Epidem Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1287–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraft RA, Jahren A, Saudek C. Clinical-scale investigation of stable isotopes in human blood: δ13C and δ15N from 406 patients at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3683–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connell T, Hedges R, Healey M. Isotopic comparison of hair, nail and bone: modern analyses. J Archaeol Sci. 2001;28:1247–55 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchardt B, Bunch V, Helin P. Fingernails and diet: stable isotope signatures of a marine hunting community from modem Uummannaq, North Greenland. Chem Geol. 2007;244:316–29 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuhnle GG, Joosen AM, Kneale CJ, O'Connell TC. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios of urine and faeces as novel nutritional biomarkers of meat and fish intake. Eur J Nutr. Epub 2012 Mar 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livingstone MB, Black A. Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. J Nutr. 2003;133:S895–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macdiarmid J, Blundell J. Assessing dietary intake: who, what and why of under-reporting. Nutrition Research Reviews. 1998;11:231–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]