Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a human gammaherpesvirus carried by more than 90% of the world’s population, is associated with malignant tumors such as Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin lymphoma, post-transplant lymphoma, extra-nodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinomas in immune-compromised patients. In the process of infection, EBV faces challenges: the host cell environment is harsh, and the survival and apoptosis of host cells are precisely regulated. Only when host cells receive sufficient survival signals may they immortalize. To establish efficiently a lytic or long-term latent infection, EBV must escape the host cell immunologic mechanism and resist host cell apoptosis by interfering with multiple signaling pathways. This review details the apoptotic pathway disrupted by EBV in EBV-infected cells and describes the interactions of EBV gene products with host cellular factors as well as the function of these factors, which decide the fate of the host cell. The relationships between other EBV-encoded genes and proteins of the B-cell leukemia/lymphoma (Bcl) family are unknown. Still, EBV seems to contribute to establishing its own latency and the formation of tumors by modifying events that impact cell survival and proliferation as well as the immune response of the infected host. We discuss potential therapeutic drugs to provide a foundation for further studies of tumor pathogenesis aimed at exploiting novel therapeutic strategies for EBV-associated diseases.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, Bcl family members, Apoptosis, Drugs therapy

1. Introduction

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), an anti-apoptotic member of the Bcl family, was initially identified as a proto-oncogene at the breakpoint of the (14, 18) chromosomal translocation detected in human B-cell follicular lymphoma (Bakhshi et al., 1985). To date, 19 members of the Bcl family have been characterized. Based on their structural features and roles in regulating apoptosis, the Bcl family can be divided into three subgroups. (1) ‘Multi-domain’ anti-apoptotic members, containing multiple Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains (BH1–4) and promoting cell survival. This subgroup includes Bcl-2-like long, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, Bcl-2-like 2, Bcl-w, myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (MCL-1), and Bcl-2 fetal liver (bfl-1). (2) ‘Multi-domain’ pro-apoptotic members, lacking only the BH4 domain characteristic of proteins that promote survival and induce cell death. This subgroup includes Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), Bcl-2-antagonist/killer (BAK), Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death (Bad), and Bcl-2-related ovarian killer (Mtd/Bok). (3) ‘BH3 domain-only’ members (Puthalakath and Strasser, 2002), sensors of distinctive cellular stresses (Huang and Strasser, 2000; Puthalakath and Strasser, 2002) that share sequence homology only in the BH3 domain. This subgroup includes the death-promoting Bcl-2 homolog (BIK), Bcl-2-interacting protein (Bid), p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA/Bbc3), and the Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (BIM).

Most studies have indicated that proteins of this gene family act mainly by forming among themselves a complex network of promiscuous homo- and heterodimers (Hsu et al., 1997). The anti-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family induce oncogenesis by protecting cells from various apoptotic stimuli and triggers, such as DNA-damaging irradiation (Cory et al., 2003) and chemotherapeutic drugs, not by facilitating proliferation. However, evidence has demonstrated that over-expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-w, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2) interferes with the cell cycle by delaying the progression to S phase and inhibiting initiation of the cell cycle (Jamil et al., 2005; Zinkel et al., 2006). Pro-apoptotic members, such as Bax and BAK, were believed to undergo conformational changes and insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane as homo-dimerized multimers when death signals were received. This causes the release of apoptotic molecules from the inter-membrane space, such as the second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (also known as SMAC), which leads to activation of caspase-9 (Riedl and Shi, 2004), and an apoptosis-inducing factor, which, in turn, leads to cell death. However, this pro-apoptotic activity is blocked via anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members interacting with Bax and BAK. BH3-only proteins are transcriptionally or post-translationally activated by extracellular pro-apoptotic signals and intracellular damage. These proteins can then use their BH3 domains as ligands to activate Bax and BAK directly or to suppress the anti-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (Wei et al., 2001; Zong et al., 2001), to regulate apoptosis. Usually, the ratio of anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family determines whether a cell lives or dies (Cory et al., 2003; Danial and Korsmeyer, 2004).

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), with a double-stranded DNA genome, was first discovered under electron microscopy in cultured Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cells. EBV establishes a lifelong infection in more than 90% of the population, which makes it the most successful human virus. Interestingly, infection in childhood is usually asymptomatic, but in adolescence the result is often infectious mononucleosis. Furthermore, EBV participates in germinal center reaction (Spender and Inman, 2011) and resides in the latent phase. When infected B-lymphocytes receive a stimulus to divide into plasma cells and the EBV immediately-early genes BRLF1 and BZLF1 are expressed, the viral lytic reaction takes place (Thorley-Lawson and Gross, 2004; da Silva and de Oliveira, 2011). Much time has been devoted to clarifying the impact of EBV on the development of tumors and it has been found that EBV is associated with a great many malignancies, including post-transplant lymphoma disorders, BL, extra-nodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinomas in immune-compromised patients.

In the two phases (latent and lytic) of the EBV life cycle (Rickinson and Kieff, 2007), EBV-infected cells express ~100 genes including, in the latent phase, EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C, the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1), LMP-2A, LMP-2B, EBV-encoded small RNAs-1 (EBER-1), and EBER-2, and in the lytic phase, BZLF1, the EBV Bam HI fragment H rightward open reading frame 1 (BHRF1), and the EBV Bam H1 A fragment leftward reading frame 1 (BALF1) (Kalla and Hammerschmidt, 2012). Most of their functions have been characterized. For example, EBNA1 is necessary for the transactivation of the C promoter (Cp) viral promoter (Altmann et al., 2006) as well as the latency and replication of the virus. In some microenvironments, EBNA1 is thought to suppress cell death (Kennedy et al., 2003). BARF1 and BZLF1, encoding viral transcription factors, switch the infection from latent to lytic phase (Feederle et al., 2000; Sinclair, 2003). EBV-expressed microRNAs (miRNAs) play a crucial role in development, the cell cycle, and immunity and contribute to cancer-associated pathology (Lee and Dutta, 2009; Forte and Luftig, 2011). However, the molecular interactions between EBV and host cells, especially between EBV and Bcl-2 family proteins, are still poorly understood. The results of some studies suggest that elucidation of the relation between EBV and the Bcl-2 family is important in understanding the pathogenesis of EBV-associated diseases. This review summarizes current knowledge on the interactions between EBV-encoded products and Bcl-2 family members in the lytic and latent phases, and the details of the apoptotic pathway in EBV-infected cells, which contribute into the establishment of EBV latency and carcinogenicity, as well as the effects of current therapeutic drugs.

2. Impact of EBV gene products on Bcl-family members during lytic infection

2.1. BZLF1 down-regulates the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL

The EBV immediate-early gene BZLF1 encodes the transcription factor Zta (also called Zebra, Z, and EB1) and is related to the cellular activating protein-1 (AP-1). In latently infected B cells, its protein is a core regulator of the switch from the latent to the lytic phase (Countryman and Miller, 1985). After primary infection, BZLF1 is expressed very early in B cells. However, its early expression does not immediately initiate the EBV lytic cycle but promotes the proliferation of resting memory and naive B cells (Kalla et al., 2010). It is also very important for maintaining cell survival during the lytic phase. Unexpectedly, BZLF1 down-regulates the expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL by down-regulating the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-associated invariant chain (CD74) in CD4+ T cells (Zuo et al., 2011). This result was confirmed in Akata-A3 cells (Zuo et al., 2011). In addition, BZLF1-mediated down-regulation of CD74 involves repression of activation of the 65-kDa (p65) member of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) family, which can transactivate Bcl-2 family genes (Lantner et al., 2007). NF-κB family members are crucial for inducing expression of a number of genes involved in immunity (Baldwin, 2001). Thus, the capacity of BZLF1 to decrease the expressions of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL is essential for EBV to escape the host response during the lytic phase.

2.2. BHRF1

BHRF1, as a latent (Hayes et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2009) and lytic gene encoding a 17-kDa component of the restricted early antigen complex (ER-A), is highly conserved in all EBV isolates. It contains three conserved BH domains, BH1–3, which are characteristic of the Bcl-2 family. BHRF1 and Bcl-2 have a similar cellular distribution, both primarily localized in the mitochondrial (Hickish et al., 1994), endoplasmic reticulum, and nuclear membranes. Earlier studies showed that BHRF1 is not responsible for the transformation of B lymphocytes induced by EBV and delays apoptosis during viral replication in vitro. However, lytic BHRF1 transcripts and latent BHRF1 transcripts have been found in EBV-positive B-cell lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma, and EBV-transformed tightly latent B-cell lines in vitro (Xu et al., 2001; Yu et al., 2001; Howell et al., 2005). These findings demonstrated that BHRF1 protects various cell types from apoptosis induced by a wide range of external stimuli, tumor necrosis factor-α, activated monocytes, radiation, or anti-tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily member 6 antibody. So BHRF1 is a viral homologue of the human cellular Bcl-2 protein in both structure and function. However, the anti-apoptotic activity of BHRF1 is not exactly equivalent to that of Bcl-2. Studies of the three-dimensional (3D) structures showed that prenylated rab acceptor 1 (PRA1) expression regulates the anti-apoptotic activity of BHRF1, but not that of Bcl-2 (Li et al., 2001). Since the activities of BHRF1 and Bcl-2 are modulated by specific mechanisms, such as diverse binding with distinctly different functions, BHRF1 probably exerts its pro-survival function in a manner similar to that previously found for human anti-apoptosis Bcl-2 members.

2.2.1. BHRF1 and Bok

A pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, Bok, was first cloned from the ovarian complementary DNA (cDNA) library of a rat. Studies showed high expression of Bok messenger RNA (mRNA) in specific tissues, such as the testis, ovary, and uterus. The intracellular localization of Bok protein is either nuclear (involved in inducing apoptosis) (Bartholomeusz et al., 2006), cytosolic, or mitochondrial. Bok interacts only with EBV BHRF1, MCL-1, and bfl-1, but not other pro-apoptotic family members or anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, unlike other pro-apoptotic members (BIK, Bax, and BAK) (Hsu et al., 1997). Moreover, using a direct protein-protein interaction assay in vitro, Hsu et al. (1998) demonstrated that Bok-L alone, without Bok-S, interacts strongly with BHRF1. In a variety of cell types, Bok induces cell killing, but this is inhibited following co-expression with BHRF1 and MCL-1, but not with Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL (McCurrach et al., 1997; Rampino et al., 1997; Yin et al., 1997). These findings suggest that Bok plays a unique role in apoptosis, and further indicate that Bok-expression may be a target for the EBV-encoding anti-apoptotic protein BHRF1 (Marchini et al., 1991).

Previous studies have shown that anti-apoptotic proteins are likely to bind to the cell death abnormality/apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (ced4/Apaf-1) homolog which activates downstream caspase (Wu et al., 1997; Zou et al., 1997). The hetero-dimerization partners of Bok, such as BHRF1 and MCL-1, may involve in the common intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (Yakovlev et al., 2004). So it is likely that Bok exerts its pro-apoptotic function by a mechanism involving the formation of dimers with anti-apoptotic partners.

2.2.2. BHRF1 directly counters BAK

BAK is an oligomeric mitochondrial membrane protein and has a redundant but essential function when the mitochondrial release of apoptogenic factors initiates apoptosis. In a lymphocyte cell line, EBV BHRF1 binds BAK and the cell dies when it receives signals from the messenger BIM (Desbien et al., 2009). Other studies showed that BHRF1 binds to full-length BAK (Theodorakis et al., 1996; Cross et al., 2008). In fact, BHRF1 changes its structure to accommodate the BAK domain and therefore keeps the BAK inactive (Kvansakul et al., 2010). However, in cytokine-deprived cells BHRF1 appears to inhibit apoptosis by binding BIM, but not BAK (see below). In addition, although BHRF1 does not bind with Bax directly and Bax can replace BAK in cell death, it has been shown to repress the activation of Bax and BAK to preserve mitochondrial function (Kvansakul et al., 2010). So why BHRF1 binds an apparently irrelevant protein is a conundrum.

2.2.3. BHRF1 and BOD

The Bcl-2-related ovarian death gene (BOD) was first identified as an ovarian Bcl-2-related, Bcl-2 homology (BH3) domain-only protein in an ovarian fusion cDNA library (Hsu et al., 1998). It has three variants (long, medium, and short), all of which contain a consensus BH3 domain without the other BH domains detected in channel-forming Bcl-2 family members. In a yeast cell assay, Hsu et al. (1998) found that the C-terminal BH3 domain-containing region of BOD interacted strongly with EBV BHRF1 and all known mammalian anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w/bcl-2-2, bfl-1, and MCL-1), but not with pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Bok, Bax, Bad, and BAK). While studies on BOD are scarce, northern and southern blot analyses revealed that, unlike Bok, BOD is expressed in various tissues (mainly the spleen and kidney) and has been highly conserved during the evolution of mammals (Hsu et al., 1998). This suggests that, like BAD, it may function as an adaptor protein for upstream signals and induce cell-killing by hydro-isomerization with diverse anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins in a variety of cell lines, especially in leukocytes. The exact role of BOD in the intracellular mechanism underlying apoptosis needs further study.

2.2.4. BHRF1 interacts with BIK, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL

BIK, a potent pro-apoptotic protein, shares only the BH3 domain and the C-terminal trans-membrane domains with other members of the Bcl-2 family, such as Bax, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL. Most data show that BIK promotes cell death and heterodimerizes with survival-promoting proteins. Evidence is accumulating that BIK interacts with the viral anti-apoptotic protein EBV BHRF1, and various cellular anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (Boyd et al., 1995), and that this activity of BIK is inhibited following co-expression of EBV-BHRF1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL (Boyd et al., 1995). Further studies revealed that an 18-amino-acid region in the BH3 domain constitutes the critical heterodimerization domain. EBV BHRF1 is a viral homolog of the human cellular Bcl-2 protein both in structure and function (as noted above), indicating that BHRF1 might interact indirectly with Bcl-2 via BIK and prevent apoptosis during EBV replication, prolong the lifespan of EBV-infected cells, and potentiate viral persistence and spread.

2.2.5. BHRF1 binds to BIM

BIM exists in three major isoforms (BIMEL, BIML, and BIMS) and is expressed in a variety of cell types, especially lymphocytes. Most reports show that BIM is a key regulator of life and death decisions (Anderton et al., 2008; Paschos et al., 2009). Thus, it is not surprising that EBV BHRF1 binds to the BH3-only peptide BIM and interacts strongly with its protein (Flanagan and Letai, 2008). Further study has shown that BHRF1 blocks apoptosis by binding to a crucial, lethal fraction of the BIM, but not the general BIM pool (Desbien et al., 2009). Moreover, the structure of BHRF1 in complex with BIM confirms that BHRF1 can counteract BIM directly (Kvansakul et al., 2010). These findings may facilitate the exploitation of small-molecule inhibitors of BHRF1 to improve the poor prognosis in EBV-associated diseases, since BHRF1 confers strong chemoresistance and current small organic inhibitors of Bcl-2 do not target BHRF1.

2.2.6. BHRF1 inhibits BH3-only proteins PUMA and Bid

PUMA (Nakano and Vousden, 2001) and Bid are both BH3-only proteins and are required for the induction of apoptosis. Accumulating evidence shows that BHRF1 is associated with PUMA and Bid, since it binds to them and interacts strongly with Bid protein (Flanagan and Letai, 2008; Kvansakul et al., 2010). EBV BHRF1 promotes cell survival by directly repressing pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins including PUMA and Bid (Kvansakul et al., 2010). The structure of BHRF1 in complex with PUMA or Bid is still unclear. However, it is possible that BHRF1 changes its structure to accommodate the PUMA or Bid domain, because Bid is considered to be an activator, like BIM (Letai et al., 2002).

2.3. BALF1 associates with Bax and BAK

BALF1 protein is encoded by the smaller open reading frame of the EBV genome and has sequence homology with the Bcl-2 family, especially in the functionally important BH1 and BH2 domains. Interestingly, compared to BHRF1, there is more similarity among BALF1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL. Bax and BAK, as Bcl-2 family members, were found to associate with BALF1 in Henrietta Lacks (HeLa) cells. This association provides a possible mechanism for the anti-apoptotic function of BALF1. A recombinant green fluorescent protein-BALF1 fusion protein experiment also demonstrated the anti-apoptotic function of BALF1 in anti-Fas-treated HeLa cells. Similar results were found with anti-Fas plus interferon-γ (IFN-γ) when both cycloheximide and TNF-α or chloromethyl X-rosamine (CMXRos) staining were used to induce apoptosis (Marshall et al., 1999). However, a report showed that EBV BALF1 fails to protect cells from Bax-induced apoptosis in the DG75 B cell (EBV-negative BL lymphoma) (Bellows et al., 2002), so BALF1 lacks an anti-apoptotic function. Taken together, although the function of BALF1 is not yet clear, it remains possible that BALF1 interrupts the apoptotic pathway in EBV-infected cells by interacting with pro-apoptotic proteins, such as Bax and BAK.

2.4. BARF1 activates Bcl-2

The EBV Bam HI-A rightward frame 1 (BARF1) gene is translated to form an early protein that is homologous to the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and the human cloning stimulating factor I receptor (HCSF-IR). Previous studies suggested that BARF1 activity includes both an immunomodulatory function and oncogenicity. BARF1 protein modulation of the host immune response to the virus is achieved by the protein acting as a receptor of human colony-stimulating factor (Hcsf-1) (Strockbine et al., 1998) and as an inhibitor of α-interferon secretion from mononuclear cells (Cohen and Lekstrom, 1999). The oncogenic activity of the BARF1 gene, specifically located in its N-terminal domain, can induce malignant transformation in the EBV-negative Louckes B cell line and aggressive tumors in new-born rats and rodent cells (Sheng et al., 2001). In addition, it can immortalize primary monkey kidney epithelial cells in vitro. To explain the mechanism of malignant transformation induced by BARF1, some reports suggested that the N-terminal domain of the BARF1 gene is able to activate anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression in rodent fibroblasts with deletion mutations (Sheng et al., 2001). A similar activation of Bcl-2 expression was shown in BARF1-transfected, EBV-negative Akata cells (Sheng et al., 2003). These findings support the hypothesis that BARF1 activates Bcl-2 expression to resist apoptosis and that the cooperation of Bcl-2 with BARF1 is indispensable for inducing malignant transformation. However, the exact mechanism of this cooperation is not very clear. This study also suggested that the apoptosis induced by serum deprivation in Balb/c3T3 cells is mediated by myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-MYC) and is then blocked by the up-regulated expression of Bcl-2 induced by BARF1 (Sheng et al., 2001); but in the same cells, LMP-1 does not activate Bcl-2 protein expression. If the association between BARF1 and Bcl-2 is more extensive than that between BARF1 and LMP-1, it may become a common target of treatment, clinical staging, and prognosis in certain tumors.

3. Impact of EBV gene products on Bcl-family members during latency

3.1. EBNA2 interacts with various Bcl family genes

EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) is the earliest latent-cycle protein of EBV and is essential for B-cell immortalization proliferation and survival as well as chemotaxis. Pegman et al. (2006) demonstrated that in EBV-negative BL-derived cell lines EBNA2 up-regulates bfl-1 expression by interacting with EBNA2-CBF-1 (Cp-binding factor 1, also known as RPR-JK) (Zimber-Strobl and Strobl, 2001; Hayward, 2004). These interactions involve receptors of the classical Notch pathway. EBNA2 also up-regulates most other anti-apoptotic proteins such as bfl-1, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, and MCL-1 and induces expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins BIM and Bid in EBNA2-expressing cells (Kohlhof et al., 2009), which is differential in Notch1 or Notch2 IC-expressing cells. Further studies are necessary to confirm whether the Notch receptor is involved in the mechanism of EBNA2-up-regulated Bcl family gene expression. Such studies may provide a better understanding of the role of the EBNA2 in EBV-associated diseases.

3.2. EBNA3A and EBNA3C repress BIM expression

EBV nuclear antigens 3A, 3B, and 3C (EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C) are three of only six viral proteins encoded by latent EBV. Despite having the same gene structure (Bornkamm and Hammerschmidt, 2001), they have divergent functions. Genetic studies have revealed that both EBNA3A and EBNA3C (but not EBNA3B) are responsible for efficient immortalization in EBV-infected B cells (Tomkinson et al., 1993). Using recombinant EBVs established with a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) system, it was revealed that EBNA3A and EBNA3C cooperate to inhibit the activation of the tumor-suppressor gene BIM. The inhibition appears to be predominantly directed at the regulation of BIM mRNA levels (Anderton et al., 2008). This process may involve an epigenetic mechanism that can be initiated or maintained by interactions between EBNA3A and EBNA3C and suppressive marks on local chromatin. Covalent modifications to the N-terminal domains of histones can repress or silence a gene (Jaenisch and Bird, 2003; Suzuki and Bird, 2008). Clybouw et al. (2005) showed that EBV infection leads to the down-regulation of BIM protein expression, depending mainly on BIMEL expression. Most data indicate that EBNA3A and EBNA3C regulate the expression of BIM at the level of transcription (Anderton et al., 2008). Strong evidence was provided by the fact that EBNA3A and EBNA3C together inhibit the initiation of BIM transcripts (Paschos et al., 2012). What is more, EBNA3C is directly targeted to the BIM promoter (Paschos et al., 2012). Previous research has shown that in the 5′ regulator region of BIM, heritable epigenetic modifications initiated by EBNA3A and EBNA3C play a major role in determining the level of post-transcriptional BIM production expressed in EBV-infected B cells (Paschos et al., 2009).

3.3. LMP-1

LMP-1, an oncogene of EBV, encodes a 386-amino-acid integral membrane protein. Transfecting the LMP-1 gene into human B cells causes many phenotypic changes characteristic of stimulated lymphocytes, including mediation of DNA synthesis, up-regulation of various cell surface stimulation markers, and increased cell size and production of adhesion molecules (Rowe et al., 1994). These changes are among many of the transformation-associated properties of EBV reproduced by LMP-1 in various cell lines.

3.3.1. LMP-1 specifically up-regulates Bcl-2 expression

The association between LMP-1 and Bcl-2 has been a focus of research. Studies have suggested that the immortalization effect of LMP-1 on B-lymphomas is mediated by the Bcl-2 gene in many lymphoid malignancies, and that the mediation may be through cooperation between Bcl-2 and MCL-1. Lu et al. (1997) suggested that LMP-1-induced apoptosis is specifically blocked by the abnormal expression of Bcl-2 or co-expression of LMP-1 and Bcl-2 in epithelial cells (RHEK-1 cells). Down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression is also directly induced by LMP-1 when using antisense oligo-deoxynucleotides to suppress LMP-1 expression in an EBV-transformed B-cell line (Noguchi et al., 2001). Moreover, in BL cell lines in vitro, the latent viral gene LMP-1 induces the expression of Bcl-2 (Finke et al., 1992). A positive association between LMP-1 and Bcl-2 has been obtained in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related primary brain lymphomas in vivo and in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Carmilleri-Broet et al., 1995). Interestingly, reports have shown statistically significant co-expression of LMP-1 and Bcl-2 in pediatric cases although this association was not definite in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases. These results suggest that both proteins may play important complementary roles in the process of EBV-associated transformation. Up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression induced by EBV LMP-1 has been suggested as a B-cell-specific response (Rowe et al., 1994). In support of this argument, several reports have demonstrated that Bcl-2 protein expression cannot be activated by LMP-1 in human epithelial cell lines (Rowe et al., 1994) or in fibroblasts (Henderson et al., 1993). The finding supported that nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) Bcl-2 expression can be independent of LMP-1 (Sarac et al., 2001), and that EBV up-regulation of apoptosis has no relation to Bcl-2 expression. In EBV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas, the T cell type is predominant (Takano et al., 1997), which corresponds to the finding (Kim et al., 2004) that EBV does not induce the up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In addition, in EBV-positive natural killer cell lymphoma, Bcl-2 expression is not directly mediated by LMP-1 (Noguchi et al., 2001). The pathological mechanism of this specific response remains unclear but there are several possibilities. Firstly, some authors hypothesized that LMP-1 up-regulates adhesion molecules, such as cell adhesion molecule 1 (CAM-1), by activating NF-κB, leading to the up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression in B-cell lines (Rowe et al., 1994). However, the intracellular carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic region of LMP-1 has been shown to interact with signaling molecules involved in the TNFR family-activated pathway, including the transmembrane protein CD40. This then activates the NF-κB/C-jun N-terminal kinase/AP-1 pathway and finally regulates Bcl-2 expression (Noguchi et al., 2001). Secondly, the immune response of the brain can allow EBNA2 and LMP-1 over-expression in infected cells of AIDS-related primary brain lymphomas, but not in those of AIDS-related systemic lymphomas. Since the brain is immunologically privileged and does not elicit cytotoxic rejection, it allows LMP-1 to transactivate Bcl-2 (Carmilleri-Broet et al., 1995). Thirdly, alternatively, the suppression of LMP-1-induced apoptosis by Bcl-2 or co-expression of LMP-1 may be a coincidence. The pathogenesis might involve one aspect of EBV infection resulting in up-regulation of LMP-1 levels in epithelial target cells, and another aspect may be activation of Bcl-2 expression by an EBV-independent mechanism. Therefore, it is possible that in epithelial cells and fibroblasts, EBV proteins other than LMP-1 may cause immortalization.

3.3.2. LMP-1 mediates MCL-1 expression

MCL-1 was first identified as a novel EBV gene active in early cell differentiation induced in a human myeloid leukemia cell line (Kozopas et al., 1993). MCL-1 protects Chinese hamster ovary cells from apoptosis caused by c-MYC over-expression and heterodimerizes with Bax. Moreover, because in EBV-infected B cells the regulation of MCL-1 by LMP-1 occurs at an early stage, prior to up-regulation of Bcl-2 and decreased MCL-1 levels, it was suggested that MCL-1 functions as a rapid, crucial immediate-early response effector of cell survival (Wang et al., 1996). Kim et al. (2012) also showed that up-regulation of MCL-1 by LMP-1 contributes to survival in rituximab-treated B-cell lymphoma cells. Interestingly, the down-regulation of MCL-1 expression is also blocked by LMP-1 in response to apoptotic stimulation. This is supported by the finding that LMP-1 promotes survival in the EBV-negative BL cell line BL41 (Wang et al., 1996). Therefore, the expression of MCL-1 mediated by LMP-1 is likely to play an important role in the immediate-early response in EBV infection. However, the significance of decreasing MCL-1 by LMP-1 (long-term expression) is still unclear and needs further study.

3.3.3. LMP-1 drives the anti-apoptotic bfl-1 gene

B-lymphocyte decision depends on activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and the CD40 receptor and involves the participation of tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 2. It is mediated via the carboxyl terminal activating region 2 (CTAR2) associated with the CTAR1 region of LMP-1. This point was strongly supported by the finding that the expression of bfl-1 represses apoptosis activated by the amino-terminal six-transmembrane domain (6TM) of LMP-1 (Pratt et al., 2012). In this process, like the B-cell receptor, the 6TM of LMP-1 activates an unfolded protein response (UPR), and then induces apoptosis, but the carboxy-terminal domain of LMP-1 activates the transcription of bfl-1 to repress apoptosis by the UPR. These findings indicate that bfl-1 contributes to the long-term survival of EBV-infected B cells in a way similar to the combined roles of CD40 and the B-cell receptor.

3.4. LMP2A increases the expression of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2

EBV latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) was identified in germinal center B cells (Babcock et al., 2000), but its transcripts are consistently found in all forms of EBV latency, including resting memory B cells, infectious mononucleosis, Hodgkin lymphoma, BL, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (Thorley-Lawson and Gross, 2004; Rickinson and Kieff, 2007). Thus, LMP2A is important in EBV-associated diseases. Many studies have demonstrated that it has a critical function to rescue cells from apoptosis by potentially altering the balance of pro-apoptotic and pro-survival Bcl family members, particularly by mediating the expression of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. For example, using the model of LMP2A transgenic E mice and H-ras17 mice, it was demonstrated that LMP2A activates Ha-Ras, and in turn preferentially activates the phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, normally imparting an essential survival signal in response to B-cell receptor signaling. Importantly, both the PI3K/Akt and the Raf/ERK kinase (MEK)/extracellular-signal-related kinase (ERK) pathways, downstream of the Ras family, raise NF-κB, which is a critical mediator of Bcl-xL (Steelman et al., 2004). Therefore, LMP2A probably maintains cell survival by modulating Bcl-xL levels and Bcl-2 expression patterns in the absence of B cell receptor signaling (Portis and Longnecker, 2004). Other studies have shown that LMP2A can bypass the intact p53 pathway in the c-MYC model of lymphomagenesis (Bieging et al., 2009; 2010). Interestingly, the regulation was selective for Bcl-2, since the NF-κB inhibitor apparently affects the levels of Bcl-2 only in LMP2A/HEL-Tg B cells, not in the Bcl-2-positive HEL-Tg B cell (Swanson-Mungerson et al., 2010).

3.5. MIR-BART5 suppresses PUMA expression

A microRNA (miRNA) is a new kind of small RNA (~22 nt in length), which negatively regulates gene expression by inducing mRNA degradation or repressing translation (Grundhoff et al., 2006). EBV was the first human virus to express miRNAs, such as MIR-BamHI A rightward transcripts 5 (BART5) (Pfeffer et al., 2004). Unlike cellular miRNAs (Grundhoff et al., 2006), the roles of most EBV miRNAs remain largely unknown. Previous studies suggested that EBV miRNAs are central mediators of viral gene expression, but recently experiments have demonstrated that MIR-BART5 promotes host cell survival by targeting PUMA expression and contributes to the establishment of latent infection in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and EBV germinal center cells (Choy et al., 2008). Given that MIR-BARTs are abundantly expressed in epithelial cells latently infected with EBV but are less expressed in B cell lines (Cai et al., 2006), they may be important in epithelial carcinogenesis. Another recent study showed that PUMA is also mediated by cellular miRNAs, including miRNA 221/222, thereby inducing cell survival (Zhang et al., 2010). Hence, more experiments are required to understand fully whether cellular miRNAs and MIR-BARTs trigger the same sequence in the 3′-untranslated region of PUMA mRNA and whether other mechanisms are involved in mediating PUMA expression during the EBV infection process.

3.6. EBER-1 and EBER-2 up-regulate Bcl-2 protein expression

The EBV-encoded small RNAs EBER-1 and EBER-2 are small nuclear RNAs transcribed by RNA polymerase III and are the most abundant EBV transcripts expressed. Various studies have shown that EBV inhibition of apoptosis and up-regulation of the Bcl-2 protein are essential for the malignant phenotype (Marin et al., 1995; Komano et al., 1998). Previous reports also provided direct evidence that EBV up-regulates Bcl-2 expression by repressing the activation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) (Komano et al., 1999). This allows c-MYC to exert its oncogenic function, and eventually results in the inhibition of apoptosis. Wong et al. (2005) demonstrated that the EBER-induced up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression involves the inactivation of PKR and might inhibit p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and C-jun phosphorylation. The exact mechanism remains to be identified and may provide a novel treatment strategy for EBV-associated malignancies.

4. Drugs targeting Bcl family members in EBV-associated diseases

Increasing evidence points to a crucial function for the disruption of Bcl family proteins by EBV in regulating apoptosis in various cancers and in chemotherapy, and it is clear that exploiting this specific interaction is an appealing approach for new anticancer drugs. In recent years, therapeutic options for Bcl family members and EBV-encoded products have evolved and improved (Leber et al., 2010; Ghosh et al., 2012). However, therapies targeting Bcl family proteins in EBV-associated diseases have lagged behind.

Despite this, there have been important research findings in recent years. Early trials aimed mainly to exploit antisense-based strategies to repress the expression of Bcl-2 or MCL-1 by knocking down LMP-1 expression. For example, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides were directed at LMP-1 mRNA to knock down LMP-1 expression and thereby suppress its function. This was associated with inhibition of Bcl-2 expression in EBV-immortalized B cells (Kenney et al., 1998). With the development of Bcl family protein inhibitors for anticancer therapy, the first such inhibitor, G3139 (Genasense/oblimersen), was used in treating EBV-associated diseases (Loomis et al., 2003). It was shown that G3139 effectively suppresses Bcl-2 protein expression and has powerful anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in EBV-positive lymphoblastoid cells. Given that antisense oligodeoxynucleotides cause inflammatory responses and monotherapy most likely induces resistance in tumor cell clones due to the selection process in the tumor population, it is necessary and feasible to apply a combinatorial strategy in the treatment of cancer, especially in EBV-associated diseases. Such approaches have already been investigated in EBV-associated lymphoproliferative diseases using G3139 in combination with rituximab (Loomis et al., 2003). Preclinical and clinical trials have investigated the antitumor effects of this combinatorial therapy in mouse xenograft tumor models (Klasa et al., 2000; Miayake et al., 2000; Wachek et al., 2001) as well as its toxicity profile in human phase I testing (Jansen et al., 2000; Waters et al., 2000; Morris et al., 2002). This suggests a promising nontoxic and effective therapy for EBV-positive lymphoproliferative diseases. Abdulkarim et al. (2003) also demonstrated that treatment with Cidofovir combined with ionizing radiation leads to tumor remission without increasing toxicity in EBV-positive cells (Raji and C15) in nude mice. This approach is likely to greatly improve conventional cancer therapies. A recent exciting discovery showed that two new Bcl-2 inhibitors, HA14-1 and ABT-737, applied in combined treatments strongly induce apoptosis in EBV-associated diseases (Srimatkandada et al., 2008; Pujals et al., 2011). HA14-1 in combination with bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor) synergistically enhances anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in EBV-positive lymphoproliferative diseases. This small molecule inhibitor has a high binding affinity to Bcl-2 and efficiently induces apoptosis by repressing BAK/Bcl-2 interaction (Azmi and Mohammad, 2009). ABT-737 allows Bax activation by a murine double minute-2 (MDM2) inhibitor by disrupting Bax/Bcl-2 interaction in latency III EBV-positive cells. ABT-737, a BH3 mimetic, represses the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-w, and Bcl-xL and is the highest affinity drug reported to be currently in preclinical or clinical testing (Vogler et al., 2009). Another Bcl protein inhibitor, obatoclax, binds to all anti-apoptotic Bcl family proteins in vitro (Nguyen et al., 2007). These findings suggest that this strategy may have broader applications for other EBV-positive diseases with abnormal expression of Bcl proteins. The combination of EBV-based therapies to reduce expression and a Bcl family protein inhibitor to repress function or disrupt interaction of the protein may provide a ‘double whammy’ to tumor cells in the treatment of EBV-associated diseases.

5. Conclusions

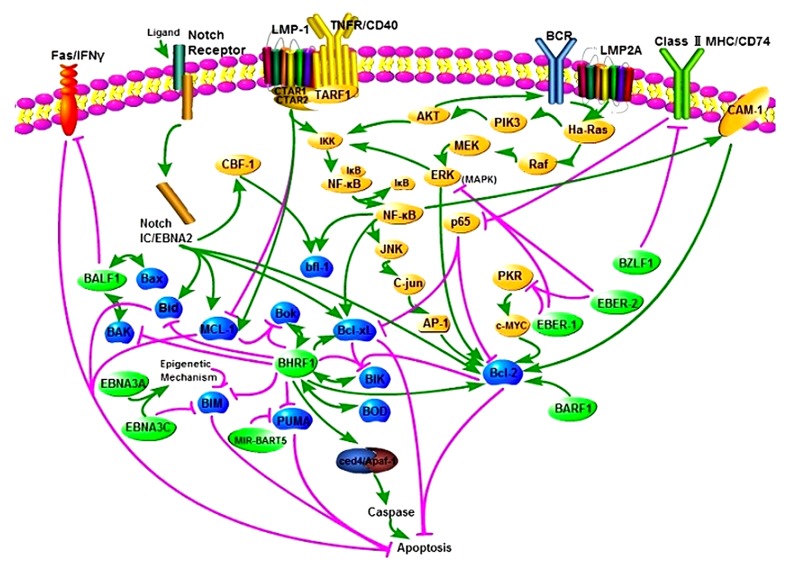

Apoptosis plays a critical role not only in normal development but also in a variety of human disorders including cancer, neurodegeneration, and autoimmunity (White, 1996). EBV interacts with various intracellular factors, especially Bcl-2 family members, by impacting on multiple apoptotic pathways (Fig. 1). Moreover, the Bcl-2 family member-mediated intrinsic apoptotic pathway is involved. From the results of recent studies, most Bcl-2 family members are targeted by EBV-expressed products. In this complex network, EBV BHRF1, Bcl-2, and EBNA2 are prominent. Although the actions of EBV do not all occur in the same cell, it is still probable that the NF-κB pathway is a common target by which EBV disturbs the normal apoptosis pathway, combined with BHRF1, Bcl-2, and ENBA2. These findings may bring about new insights for targeting therapy and prognosis of EBV-associated tumors.

Fig. 1.

Epstein-Barr virus interactions with the Bcl-2 protein family and apoptosis

EBV infection disrupts normal cell death and survival pathways in various human tumor cells, including lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells. Interconnected signaling pathways mediate apoptosis. Pro-apoptotic signals are mediated by BZLF1, down-regulating Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression involving the repression of CD74 and p65. Pro-survival pathways occur mainly via EBV gene products (shown in light green). The activation of BHRF1 results in repression of the pro-apoptotic proteins BIM, PUMA, and Bid; the activation of BARF1 causes the up-regulation of pro-survival Bcl-2 protein levels; LMP-1 stimulation results in the CTAR1 and CTAR2 regions of LMP-1 interacting with TNFR/CD40, including TARF1, and then activates the NF-κB/c-JNK/AP-1 pathway and CAM-1, and finally up-regulates bfl-1 and Bcl-2 expression. In addition, the activation of LMP-1 inhibits or activates MCL-1; MIR-BART5 stimulation results in the repression of the pro-apoptotic protein PUMA; the activation of LMP2A results in activation of the Ha-Ras, PI3K/Akt pathway and the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway as well as NF-κB, and then increases the expression of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. All of these result eventually in the inhibition of apoptosis. Unfortunately, the results of other interactions are not clear. BHRF1 is known to interact with the pro-apoptotic proteins Bok, BAK, BOD, and BIK. BALF1 interacts with Bax and BAK. Likewise, EBNA2 interacts with the pro-survival proteins Bcl2L1, Bcl-2, and MCL-1 and the pro-apoptotic proteins BIM and Bid. EBNA3A and EBENA3C inhibit BIM expression, and EBNA3C targets BIM directly. EBER-1 and EBER-2 up-regulate Bcl-2 expression by inhibiting PKR or MAPK and C-jun. EBNA2, mimicking Notch-IC, activates CBF-1 to up-regulate bfl-1. EBV also impacts the apoptosis pathway via the FAS/IFN-γ receptor and by binding to ced4/Apaf-1. Interestingly, the Bcl-2 family members, with which diverse EBV gene products interact, are essential in the ‘decision’ step of apoptosis, and then the activation of caspases mediates the ‘execution’ phase. These are both important steps in apoptosis

Although it is not clear how these interactions proceed in detail, what we know already provides an exciting glimpse into how they contribute to the establishment of EBV latency and the formation of tumors. After infection, BZLF1 is expressed immediately in the majority of primary B cells. Once the viral DNA is methylated, BZLF1 initiates the lytic cycle. Surprisingly, BZLF1 down-regulates the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Coincidently, this action is neutralized by BHRF1 protein (Zuo et al., 2011). Obviously, the cooperation not only allows adequate time to synthesize and accumulate infectious viral progeny, but also enables BZLF1 to efficiently evade CD+ T cell responses. BHRF1 is highly expressed in the first 24 h of infection as well as in the lytic phase, and can repress apoptosis by interacting with the pro-apoptotic protein directly and the pro-survival protein indirectly, which favors rapid transit through the cell cycle (Dawson et al., 1998). Thus, the anti-apoptotic function of BHRF1 might contribute to the accomplishment of viral replication and assembly during the lytic phase. The second Bcl-2 homolog, BALF1, also appears to promote cell survival since it can associate with Bax and BAK. The development of events in the lytic phase is divided to three components: immediately-early, early, and late. BHRF1, BALF1, and BARF1 are early genes, and only BZLF1 is an immediately-early gene. The N-terminal 49 amino-acids of BARF1 appear to be responsible for its transforming capacity (Sheng et al., 2001). However, viruses lacking the BARF1 gene are not defective in their ability to immortalize B cells in vitro, suggesting that other mechanisms maybe involved. BARF1 itself might induce cell transformation by cooperating with Bcl-2 protein, since BARF1 activates anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 in various cells. Thus, after infection, the infectious cell escapes immunosurveillance, survives to proliferate, and completes viral replication and assembly while accumulating infectious viral progeny.

About one week after infection, EBV ceases to express lytic genes, while latent genes are fully expressed. In fact, EBV might evade the host defenses more effectively by withdrawing into a latent status. During latency, several crucial latent genes, including EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3, LMP-1, LMP2A, and EBERs, are expressed. Studies with EBV recombinants have shown that EBNA2 plays a crucial role in the transformation process. This effect may be at least partially relevant to the up-regulation of the anti-apoptotic protein bfl-1 induced by EBNA2, since the process of induction involves the Notch receptor, a pathway implicated in the progression of T-cell tumors in humans (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1995). Like EBNA2, EBNA3A and EBNA3C are responsible for B cell transformation in vitro. They cooperate to repress pro-apoptotic protein BIM expression by an initial or sustained epigenetic mechanism, which causes aberrant large CpG islands utilized by DNA methylation. Therefore, EBV seems to contribute to the development of tumors by modifying the status of cellular DNA methylation, although the exact mechanism is unknown. As a classical oncogene, LMP-1 is another example of the transformation function in B cells. The effect may result from its pleiotropic functions. For example, LMP-1 can up-regulate the expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, MCL-1, and bfl-1, and the process involves the induction of cell surface adhesion and the TNFR/CD40 pathway. This provides both growth and differentiation responses and is associated with activation of a number of signaling pathways. Studies have demonstrated that LMP-1 promotes genomic instability (Liu et al., 2004; 2005), which is strongly associated with cellular transformation. Interestingly, another transmembrane protein, LMP2A, appears to have transformation effects in epithelial cells but not in B cells. LMP2A rescues cells from apoptosis by mediating Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL protein expression. Similarly, NF-κB, downstream of the PI3K/Akt pathway, can mediate the expression Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. Scholle et al. (2000) demonstrated that LMP2A can transform epithelial cells and that this capacity is mediated, at least in part, by activating the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway, indicating that LMP2A-induced activation of the pro-apoptotic protein may contribute to the transformation of epithelial cells and the long-term survival of infectious B cells. In fact, the LMP2A immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif is essential for repressing activation of the EBV lytic phase in B cells. In addition, MIR-BART5 appears to repress PUMA expression to promote infected cell survival. Intriguingly, cellular miRNAs also mediate the expression of PUMA to induce host cell survival. This supports a role for MIR-BART5 in competing with host cellular factors to favor infected cell survival and the maintenance of EBV latency. As small RNAs, EBERs have also been shown to have oncogenic functions and may confer an apoptotic-resistant phenotype by up-regulating Bcl-2 expression in EBV-associated malignant tumors. Thus, these latent genes favor the survival of infected cells, transform them, and maintain EBV latency synergistically. Finally, the EBV-mediated events generate an immortality-like environment for EBV to facilitate the establishment of viral latency and the formation of tumors.

Many questions remain. First, it is not clear which Bcl family proteins or other cellular factors are involved when the infected cell is killed to release viral progeny. Second, mRNAs may play a key role in immune evasion, because they are visible to the immune system in infected host cells, and they are highly expressed initially. Nevertheless, the exact mechanism and whether Bcl family members are involved remain a conundrum. Third, in addition to the Bcl family protein-mediated apoptotic pathway, it is still unknown which other pathways contribute to the progression of EBV-associated tumors. Fourth, the relationship between other EBV-encoded molecules and the Bcl family remains to be determined. Fifth, it is not clear which factors play a core role in the complex network. Although currently NF-κB, BHRF1, Bcl-2, and EBNA2 appear to be important components, other EBV-encoded molecules and Bcl proteins are still unknown. This is a fascinating field of study, and it can be expected that the fruits of new research will provide a better understanding of this complicated network in which the infected agents participate in carcinogenesis, uncovering new and significant information on EBV-associated tumor biology and target therapy.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81071937) and the Qianjiang Talents Project of Technology Office in Zhejiang Province, China (No. 2010R10064)

References

- 1.Abdulkarim B, Sabri S, Zelenika D, Deutsch E, Frascogna V, Klijanienko J, Vainchenker W, Joab I, Bourhis J. Antiviral agent Cidofovir decreases Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oncoproteins and enhances the radiosensitivity in EBV-related malignancies. Oncogene. 2003;22(15):2260–2271. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altmann M, Pich D, Ruiss R, Hammers Chmidt W, Wang J, Sugden B. Transcriptional activation by EBV nuclear antigen 1 is essential for the expression of EBV’s transforming genes. PNAS. 2006;103(38):14188–14193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605985103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderton E, Yee J, Smith P, Crook T, White RE. Two Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oncoproteins cooperate to repress expression of the proapoptotic tumor-suppressor Bim: clues to the pathogenesis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Oncogene. 2008;27(4):421–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Matsuno K, Fortini ME. Notch signaling. Science. 1995;268(5208):225–232. doi: 10.1126/science.7716513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azmi AS, Mohammad RM. Non-peptidic small molecule inhibitors against Bcl-2 for cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(1):13–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, Thorley-Lawson DA. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity. 2000;13(4):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakhshi A, Jensen JP, Goldman P, Wright JJ, McBride OW, Epstein AL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cloning the chromosomal breakpoint of the (14; 18) human lymphomas: clustering around JH on chromosome 14 and near atranscriptional unit on 18. Cell. 1985;41(3):899–906. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(85)80070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin AS., Jr Series introduction: the transcription factor NF-κB and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(1):3–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartholomeusz G, Wu Y, Ali Seyed M, Xia W, Kwong KY, Hortobagyi G, Hung MC. Nuclear translocation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member bok induces apoptosis. Mol Carcinogen. 2006;45(2):73–83. doi: 10.1002/mc.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellows DS, Howell M, Pearson C, Hazlewood SA, Hardwick JM. Epstein-Barr virus BALF1 is a BCL-2-like antagonist of the herpesvirus antiapoptotic BCL-2 proteins. J Virol. 2002;76(5):2469–2479. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2469-2479.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bieging KT, Amick AC, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A bypasses p53 inactivation in a MYC model of lymphoma genesis. PNAS. 2009;106(42):17945–17950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907994106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieging KT, Swanson-Mungerson M, Amick AC, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt’s lymphoma: a role for latent membrane protein 2A. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(5):901–908. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.5.10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bornkamm GW, Hammerschmidt W. Molecular virology of Epstein-Barr virus. Philosoph Transact Roy Soc B. 2001;356(1408):437–459. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd JM, Gallo GJ, Elanqovan B, Houqhton B, Malstrom S, Avery BJ, Ebb RG, Subramanian T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ. Bik, a novel death-inducing protein shares a distinct sequence motif with Bcl-2 family proteins and interacts with viral and cellular survival-promoting proteins. Oncogene. 1995;11(9):1921–1928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai X, Schafer A, Lu S, Bilello JP, Desrosiers RC, Edwards R, Raab-Traub N, Cullen BR. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(3):e23. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmilleri-Broet BS, Davi F, Feuillard J, Bourgeois C, Seilhean D, Hauw JJ, Raphaël M. High expression of latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus and BCL-2 oncoprotein in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related primary brain lymphomas. Blood. 1995;86(2):432–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choy EY, Siu KL, Kok KH, Lung RW, Tsang CM, To KF, Kwong DL, Tsao SW, Jin DY. An Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA targets PUMA to promote host cell survival. J Exp Med. 2008;205(11):2551–2560. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clybouw C, McHichi B, Mouhamad S, Auffredou MT, Bourgeade MF, Sharma S, Leca G, Vazquez A. EBV infection of human B lymphocytes leads to down-regulation of Bim expression: relationship to resistance to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2005;175(5):2968–2973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen JI, Lekstrom K. Epstein-Barr virus BARF1 protein is dispensable for B-cell transformation and inhibits alpha interferon secretion from mononuclear cells. J Virol. 1999;73(9):7627–7632. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7627-7632.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cory S, Huang DC, Adams JM. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22(53):8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Countryman J, Miller G. Activation of expression of latent Epstein-Barr herpesvirus after gene transfer with a small cloned subfragment of heterogeneous viral DNA. PNAS. 1985;82(12):4085–4089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross JR, Postigo A, Blight K, Downward J. Viral pro-survival proteins block separate stages in Bax activation but changes in mitochondrial ultrastructure still occur. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(6):997–1008. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116(2):205–219. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva SR, de Oliveira DE. HIV, EBV and KSHV: viral cooperation in the pathogenesis of human malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2011;305(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson CW, Dawson J, Jones R, Ward K, Young LS. Functional differences between BHRF1, the EBV-encoded Bcl-2 homologue, and bcl-2 in human epithelial cells. J Virol. 1998;72(11):9016–9024. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9016-9024.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desbien AL, Kappler JW, Marrack P. The Epstein-Barr virus Bcl-2 homolog, BHRF1, blocks apoptosis by binding to a limited amount of Bim. PNAS. 2009;106(14):5663–5668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901036106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feederle R, Kost M, Baumann M, Janz A, Drouet E, Hammerschmidt W, Delecluse HJ. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J. 2000;19(12):3080–3089. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finke J, Fritzen R, Ternes P, Trivedi P, Bross KJ, Lange W, Mertelsmann R, Dolken G. Expression of bcl-2 in Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines: induction by latent Epstein-Barr virus genes. Blood. 1992;80(2):459–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flanagan AM, Letai A. BH3 domains define selective inhibitory interactions with BHRF-1 and KSHV BCL-2. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(3):580–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forte E, Luftig MA. The role of microRNAs in Epstein-Barr virus latency and lytic reactivation. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(14-15):1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh SK, Perrine SP, Faller DV. Advances in virus-directed therapeutics against Epstein-Barr virus-associated malignancies. Adv Virol. 2012;2012(2012):1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/509296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA. 2006;12(5):733–750. doi: 10.1261/rna.2326106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes DP, Brink AAT, Vervoort MBHJ, Brule AJ, Middeldorp JM, Meijer CJL. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transcripts encoding homologues to important human proteins in diverse EBV associated diseases. J Clin Pathol Mol. 1999;52(2):97–103. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayward SD. Viral interactions with the Notch pathway. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(5):387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson S, Huen D, Rowe M, Dawson C, Johnson G, Rickinson A. Epstein-Barr virus-coded BHRF1 protein, a viral homologue of Bcl-2, protects human B cells from programmed cell death. PNAS. 1993;90(18):8479–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickish T, Robertson D, Clarke P, Hill M, Stefano F, Clarke C, Cunningham D. Ultrastructural localization of BHRF1: an Epstein-Barr virus gene product which has homology with bcl-2 . Cancer Res. 1994;54:2808–2811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howell M, Williams T, Hazlewood SA. Herpesvirus pan encodes a functional homologue of BHRF1, the Epstein-Barr virus v-Bcl-2. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5(6):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu SY, Lin P, Hsueh AJW. BOD (bcl-2-related ovarian death gene) is an ovarian BH3 domain-containing proapoptotic bcl-2 protein capable of dimerization with diverse antiapoptotic bcl-2 members. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12(9):1432–1440. doi: 10.1210/me.12.9.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu SY, Kaipia A, Zhu L, Hsueh AJW. Interference of BAD (Bcl-xL/Bcl-2-associated death promoter)-induced apoptosis in mammalian cells by 14-3-3 isoforms and P11. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11(12):1858–1867. doi: 10.1210/me.11.12.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang DCS, Strasser A. BH3-only proteins-essential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 2000;103(6):839–842. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33:245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jamil S, Sobouti R, Hojabrpour P, Raj M, Kast J, Duronio V. A proteolytic fragment of Mcl-1 exhibits nuclear localization and regulates cell growth by interaction with Cdk1. Biochem J. 2005;387(3):659–667. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen B, Wachek V, Heere-Ress E, Schlagbauer-Wadl H, Hoeller C, Lucas T, Hoermann M, Hollenstein U, Wolff K, Pehamberger H. Chemosensitization of malignant melanoma by BCL-2 antisense therapy. Lancet. 2000;356(9243):1728–1733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalla M, Hammerschmidt W. Human B cells on their route to latent infection-early but transient expression of lytic genes of Epstein-Barr virus. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalla M, Schmeinck A, Bergbauer M, Pich D, Hammerschmidt W. AP-1 homolog BZLF1 of Epstein-Barr virus has two essential functions dependent on the epigenetic state of the viral genome. PNAS. 2010;107(2):850–855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911948107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly GL, Long HM, Stylianou J, Thomas WA, Leese A, Bell AI, Bornkamm GW, Autner JM, Rickinson AB, Rowe M. An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in Burkitt’s lymphomagenesis: the WP/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(3):e1000341. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy G, Komano J, Sugden B. Epstein-Barr virus provides a survival factor to Burkitt’s lymphomas. PNAS. 2003;100(24):14269–14274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336099100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kenney JL, Guinness ME, Curiel T, Lacy J. Antisense to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1) suppresses LMP-1 and bcl-2 expression and promotes apoptosis in EBV-immortalized B cells. Blood. 1998;92(5):1721–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JH, Kim WS, Park C. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 protects B-cell lymphoma from rituximab-induced apoptosis through miR-155-mediated Akt activation and up-regulation of Mcl-1. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.659736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim LH, Nadarajah VS, Peh SC, Poppema S. Expression of Bcl-2 family members and presence of Epstein-Barr virus inthe regulation of cell growth and death in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Histopathology. 2004;44(3):257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klasa RJ, Bally MB, Ng R, Goldie JH, Gascoyne RD, Wong FMP. Eradication of human non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in SCID mice by BCL-2 antisense oligonucleotides combined with lowdose cyclophosphamide. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2492–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohlhof H, Hampel F, Hoffmann R, Burtscher H, Weidle UH, Hölzel M, Eick D, Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl LJ. Notch1, Notch2, and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 2 signaling differentially affects proliferation and survival of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells. Blood. 2009;113(22):5506–5515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Komano J, Sugiura M, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus contributes to the malignant phenotype and to apoptosis resistance in Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol. 1998;72(11):9150–9156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9150-9156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Komano J, Maruo S, Kurozumi K, Oda T, Takada K. Oncogenic role of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs in Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line akata. J Virol. 1999;73(12):9827. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9827-9831.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kozopas KM, Yang T, Buchan HL, Zhou P, Craig RW. MCL1, a gene expressed in programmed myeloid cell differentiation, has sequence similarity to BCL2. PNAS. 1993;90(8):3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kvansakul M, Wei AH, Fletcher JI, Willis SN, Chen L. Structural basis for apoptosis inhibition by Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(12):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lantner F, Starlets D, Gore Y, Flaishon L, Yamit HA, Dikstein R, Leng L, Bucala R, Machluf Y, Oren M, et al. CD74 induces TAp63 expression leading to B-cell survival. Blood. 2007;110(13):4303–4311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leber B, Geng F, Kale J, Andrews DW. Drugs targeting Bcl2 family members as an emerging strategy in cancer. Exp Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e18. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee YS, Dutta A. MicroRNAs in cancer. Ann Rev Pathol. 2009;4:199–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Letai A, Bassik MC, Walensky LD, Sorcinelli MD, Weiler S, Korsmeyer SJ. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(3):183–192. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li LY, Shih HM, Liu MY, Chen JY. The cellular protein PRA1 modulates the anti-apoptotic activity of Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1, a homologue of Bcl-2, through direct interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):27354–27362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu MT, Chen YR, Chen SC, Hu CY, Lin CS, Chang YT, Wang WB, Chen JY. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces micronucleus formation, represses DNA repair and enhances sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents in human epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(14):2531–2539. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu MT, Chang YT, Chen SC, Chuang YC, Chen YR, Lin CS, Chen JY. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 represses p53-mediated DNA repair and transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2005;24(16):2635–2646. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loomis R, Carbone R, Reiss M, Lacy J. Bcl-2 antisense (G3139, Genasense) enhances the in vitro and in vivo response of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease to rituximab. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(5):1931–1939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu JY, Chen JY, Hsu TY, Yu CY, Su IJ, Yang CS. Cooperative interaction between Bcl-2 and Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 in the growth transformation of human epithelial cells. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(11):2975–2985. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marchini A, Tomkinson B, Cohen JI, Kieff E. BHRF1, the Epstein-Barr virus gene with homology to Bcl2, is dispensable for B-lymphocyte transformation and virus replication. J Virol. 1991;65(11):5991–6000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5991-6000.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marin MC, Hsu B, Stephens LC, Brisbay S, McDonnell TJ. The functional basis of c-myc and bcl-2 complementation during multistep lymphomagenesis in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217(2):240–247. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marshall WL, Yim C, Gustafson E, Graf T, Sage DR, Hanify K, Williams L, Fingeroth J, Finberg RW. Epstein-Barr virus encodes a novel homolog of the bcl-2 oncogene that inhibits apoptosis and associates with Bax and Bak . J Virol. 1999;73(6):5181–5185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5181-5185.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCurrach ME, Connor TM, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Lowe SW. Bax-deficiency promotes drug resistance and oncogenic transformation by attenuating p53-dependent apoptosis. PNAS. 1997;94(6):2345–2349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miayake H, Tolcher A, Gleave ME. Chemosensitization and delayed androgen-independent recurrence of prostate cancer with the use of antisense Bcl-2 oligodeoxynucleotides. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2000;92(1):34–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris MJ, Tong WP, Cordon-Cardo C, Drobnjak M, Kelly WK, Slovin SF, Terry KL, Siedlecki K, Swanson P, Rafi M, et al. Phase I trial of BCL-2 antisense oligonucleotide (G3139) administered by continuous intravenous infusion in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:679–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53 . Mol Cell. 2001;7(3):683–694. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nguyen M, Marcellus RC, Roulston A, Watson M, Serfass L, Madiraju SRM, Goulet D, Viallet J, Bélec L, Billot X, et al. Small molecule obatoclax (GX15-070) antagonizes MCL-1 and overcomes MCL-1-mediated resistance to apoptosis. PNAS. 2007;104(49):19512–19517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709443104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noguchi T, Ikeda K, Yamamoto K, Yoshida I, Ashiba A, Tsuchiyama J, Shinagawa K, Yoshino T, Takata M, Harada M. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to latent membrane protein 1 induce growth inhibition, apoptosis and Bcl-2 suppression in Epstein-Barr virus EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cells, but not in EBV-positive natural killer cell lymphoma cells. Br J Haematol. 2001;114(1):84–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paschos K, Smith P, Anderton E, Middeldorp JM, White RE, Allday MJ. Epstein-Barr virus latency in B cells leads to epigenetic repression and CpG methylation of the tumor suppressor gene bim . PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(6):e1000492. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paschos K, Parker GA, Watanatanasup E, White RE, Allday MJ. BIM promoter directly targeted by EBNA3C in polycomb-mediated repression by EBV. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7233–7246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pegman PM, Smith SM, D′Souza BN, Loughran ST, Maier S, Kempkes B, Cahill PA, Gélinas C, Simmons MJ, Walls D. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 trans-activates the cellular anti-apoptotic bfl-1 gene by a CBF1/RBPJk-dependent pathway. J Virol. 2006;80(16):8133–8144. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00278-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, John B, Enright J, Marks D, Sander C, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304(5671):734–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Portis T, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) LMP2A mediates B-lymphocyte survival through constitutive activation of the Ras/PI3K/AKT pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23(53):8619–8628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pratt ZL, Zhang J, Sugden B. Simultaneously induce and inhibit oncogene of Epstein-Barr virus can the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) apoptosis in B cells. J Virol. 2012;86(8):4380. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06966-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pujals A, Renouf B, Robert A, Chelouah S, Hollville E, Wiels J. Treatment with a BH3 mimetic overcomes the resistance of latency III EBV(+) cells to p53-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2(7):e184. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Puthalakath H, Strasser A. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9(5):505–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rampino N, Yamamoto H, Ionov Y, Li Y, Sawai H, Reed JC, Perucho M. Somatic frame shift mutations in the BAX gene in colon cancers of the microsatellite mutator phenotype. Science. 1997;275(5303):967–969. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 2007:2655–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr Virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields of virology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2655–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Riedl SJ, Shi Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(11):897–907. doi: 10.1038/nrm1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rowe M, Peng-Pilon M, Huen DS, Hardy R, Croom-Carter D, Lundgren E, Rickinson AB. Up-regulation of bcl-2 by the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein LMP1: a B-cell-specific response that is delayed relative to NF-κB activation and to induction of cell surface markers. J Virol. 1994;68(9):5602–5612. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5602-5612.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sarac S, Akyol MU, Kanbur B, Poyraz A, Akyol G, Yilmaz T, Sungur A. Bcl-2 and LMP1 expression in nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Am J Otolaryng. 2001;22(6):377–382. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.28071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scholle F, Bendt KM, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A transforms epithelial cells, inhibits cell differentiation, and activates Akt. J Virol. 2000;74(22):10681–10689. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.22.10681-10689.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheng W, Decaussin G, Sumner S, Ooka T. N-terminal domain of BARF1 gene encoded by Epstein-Barr virus is essential for malignant transformation of rodent fibroblasts and activation of BCL-2. Oncogene. 2001;20(10):1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sheng W, Decaussin G, Ligout A, Takada K, Ooka T. Malignant transformation of Epstein-Barr virus-negative akata cells by introduction of the BARF1 gene carried by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 2003;77(6):3859–3865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3859-3865.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sinclair AJ. bZIP proteins of human gammaherpesviruses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(8):1941–1949. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spender LC, Inman GJ. Inhibition of germinal center apoptotic programmes by Epstein-Barr virus. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2011/829525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Srimatkandada P, Loomis R, Carbone R, Srimatkandada S, Lacy J. Combined proteasome and Bcl-2 inhibition stimulates apoptosis and inhibits growth in EBV-transformed lymphocytes: a potential therapeutic approach to EBV-associated lymphoproliferative diseases. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80(5):407–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steelman LS, Pohnert SC, Shelton JG, Franklin RA, Bertrand FE, McCubrey JA. JAK/STAT, Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/Akt and BCR-ABL in cell cycle progression and leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2004;18(2):189–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strockbine LD, Cohen JI, Farrah T, Lyman SD, Wagener F, DuBose RF, Armitage RJ, Spriggs MK. The Epstein-Barr virus BARF1 gene encodes a novel, soluble colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor. J Virol. 1998;72(5):4015–4021. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4015-4021.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(6):465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Swanson-Mungerson M, Bultema R, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A imposes sensitivity to apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(9):2197–2202. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.021444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Takano Y, Saegusa M, Masuda M, Mikami T, Okayasu I. Apoptosis, proliferative activity and Bcl-2 expression in Epstein-Barr-virus-positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin. 1997;123(7):395–401. doi: 10.1007/BF01240123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Theodorakis P, D′Sa-Eipper C, Subramanian T, Chinnadurai G. Unmasking of a proliferation-restraining activity of the anti-apoptosis protein EBV BHRF. Oncogene. 1996;12(8):1707–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1328–1337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tomkinson B, Robertson E, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins EBNA-3A and EBNA-3C are essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1993;67(4):2014–2025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2014-2025.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vogler M, Butterworth M, Majid A, Walewska RJ, Sun XM, Dyer MJS, Cohen GM. Concurrent up-regulation of BCL-XL and BCL2A1 induces approximately 1000-fold resistance to ABT-737 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(18):4403–4413. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wachek V, Heere-Ress E, Halaschek-Wiener J, Lucas T, Meyer H, Eichler HG, Jansen B. Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotides chemosensitize human gastric cancer in a SCID mouse xenotransplantation model. J Mol Med. 2001;79(10):587–593. doi: 10.1007/s001090100251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang S, Rowe M, Lundgren E. Expression of the Epstein Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 causes a rapid and transient stimulation of the Bcl-2 homologue Mcl-1 levels in B-cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4610–4613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Waters JS, Webb A, Cunningham D, Clarke PA, Raynaud F, di Stefano F, Cotter FE. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide therapy in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(9):1812–1823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Pro-apoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292(5517):727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.White E. Life, death, and the pursuit of apoptosis. Gen Dev. 1996;10(1):1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wong HL, Wang X, Chang RC, Jin DY, Feng H, Wang Q, Lo KW, Huang DP, Yuen PW, Takada K, et al. Stable expression of EBERs in immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cells confers resistance to apoptotic stress. Mol Carcinogen. 2005;44(2):92–101. doi: 10.1002/mc.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu D, Wallen HD, Nunez G. Interaction and regulation of subcellular localization of CED-4 by CED-9. Science. 1997;275(5303):1126–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xu ZG, Iwatsuki K, Oyama N, Ohtsuka M, Satoh M, Kikuchi S, Akiba H, Kaneko F. The latency pattern of Epstein-Barr virus infection and viral IL-10 expression in cutaneous natural killer/T cell lymphomas. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(7):920–925. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yakovlev AG, Giovanni SD, Wang G, Liu W. BOK and NOXA are essential mediators of p53-dependentapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(27):28367–28374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]