Background: The overall protein metabolism during denervation atrophy remains unclear.

Results: Autophagy is suppressed, whereas ribosome and protein synthesis are up-regulated in denervated muscles by proteasome-dependent activation of mTORC1.

Conclusion: Denervation does not simply induce muscle degradation but also promotes proteasome- and mTORC1-dependent muscle remodeling.

Significance: This information is beneficial for understanding the pathophysiology of other types of muscle atrophy.

Keywords: Amino Acid, Autophagy, mTOR Complex (mTORC), Proteasome, Skeletal Muscle, Denervation

Abstract

Drastic protein degradation occurs during muscle atrophy induced by denervation, fasting, immobility, and various systemic diseases. Although the ubiquitin-proteasome system is highly up-regulated in denervated muscles, the involvement of autophagy and protein synthesis has been controversial. Here, we report that autophagy is rather suppressed in denervated muscles even under autophagy-inducible starvation conditions. This is due to a constitutive activation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). We further reveal that denervation-induced mTORC1 activation is dependent on the proteasome, which is likely mediated by amino acids generated from proteasomal degradation. Protein synthesis and ribosome biogenesis are paradoxically increased in denervated muscles in an mTORC1-dependent manner, and mTORC1 activation plays an anabolic role against denervation-induced muscle atrophy. These results suggest that denervation induces not only muscle degradation but also adaptive muscle response in a proteasome- and mTORC1-dependent manner.

Introduction

Protein turnover, the net balance between protein degradation and protein synthesis, in the muscle is regulated by the metabolic demands of muscle itself and of the entire body. Muscle atrophy occurs under catabolic conditions such as denervation, fasting, immobility, and various systemic diseases. Degradation of myofibrillar components is mainly mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (1). In denervation-induced atrophy, the two E3 ubiquitin ligases, muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF1) and muscle atrophy F-box (MAFb or Atrogin-1), are markedly induced within 1 day and reach a peak at 3 days after denervation (2). In knock-out mice lacking either enzyme, the rapid loss of muscle mass upon denervation is significantly reduced (3, 4).

However, the contribution of autophagy, another major proteolytic system by which cytoplasmic materials are enclosed by the autophagosome and degraded in the lysosome, remains largely unknown. Transcription of several autophagy-related genes such as LC3b, Bnip3, GABARAP1, Atg12, Atg4B, and Beclin 1 is up-regulated in denervated muscles through FoxO3 activation (5, 6). Using an in vivo microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3)2 turnover assay, Ju et al. (7) demonstrated that autophagic flux is increased by denervation (8). However, muscle-specific deletion of Atg7 not only fails to alleviate but in fact exacerbates denervation-induced atrophy. Similarly, administration of lysosomal inhibitors does not reduce overall proteolysis during atrophy (9), although cathepsins can be induced after denervation (2, 9).

Whether denervation stimulates only protein catabolism has been questioned. Several studies have shown that protein synthesis is also increased in denervated hindlimb muscle (10) and diaphragm muscle (11). Activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) following denervation has also been suggested (12–14), although mTORC1 is generally important for maintenance of muscle mass (15, 16). However, the mechanism underlying the paradoxical up-regulation of protein synthesis and mTORC1 activation and the physiological significance of these phenomena have not been investigated.

In this study, we demonstrate that autophagy is rather suppressed in denervated muscles by a constitutive activation of mTORC1. Furthermore, mTORC1 is activated via a proteasome-mediated increase in intramuscular amino acids, which occurs following denervation. Finally, we reveal that mTORC1 activation is critical for adaptive muscle remodeling in denervated muscles through up-regulation of protein and ribosome synthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Autophagy-indicator GFP-LC3 mice were previously reported (17). C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Corp. (Tokyo, Japan) and fed a standard mouse chow and water. Most mice used in this study were between 10 and 14 weeks old. Sciatic denervation was performed by anesthetizing the mice with an intraperitoneal injection of 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Avertin®, Sigma), shaving, and making a 0.5-cm incision at middle thigh level on the lateral side of the right hindlimb, separating the muscles at the fascia, lifting out the sciatic nerve with surgical forceps, removing a 0.5-cm piece of sciatic nerve, and finally closing the incision with surgical clips. Surgery was also performed on the left hindlimb, and the sciatic nerve was visualized in the same way but left intact (sham-operated). Muscles of the left hindlimb were used as internal controls for the denervated tissues. For inhibitor experiments, bortezomib (Velcade®; Selleck Chemicals), rapamycin (LC Laboratories), and colchicine (Sigma) were injected at a dose of 1 mg/kg (i.v.), 5 mg/kg (i.p.), and 0.4 mg/kg (i.p.), respectively. A similar volume of normal saline was injected as a negative control. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (number 0130092A).

Cell Culture

C2C12 myoblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μg/ml penicillin, and streptomycin (complete medium) in a 5% CO2 incubator. To induce differentiation, the cells were incubated in differentiation medium (2% FBS in DMEM) for 7 days as described previously (18). For deprivation of serum and amino acids, differentiated C2C12 myotubes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in amino acid-free DMEM (Invitrogen) without FBS. Glutamate, leucine, and alanine (Sigma) were used for stimulation experiment at 4× physiological concentration (19).

Histology and Morphometric Measurements

Mice were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). Hindlimb muscles were harvested and further fixed with the same fixative overnight. Histological procedures for visualizing GFP in muscle cryosections of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice have been described previously (17). The samples were observed under a fluorescence microscope (IX81; Olympus) equipped with a CCD camera (ORCA ER, Hamamatsu Photonics). A ×60 PlanApo oil immersion lens (1.42 NA; Olympus) was used. Images were acquired using MetaMorph image analysis software. The number of GFP-LC3 dots was automatically counted by G-Count (G-Angstrom) and divided by the corresponding area.

To evaluate muscle atrophy, tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick transverse sections of muscles were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The cross-sectional area of 300 randomly selected myofibers was determined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared in a regular lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NaF, 0.4 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, and Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science)). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min and then boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Mouse tissues were homogenized in 9 volumes of ice-cold PBS supplemented with protease inhibitors. The homogenates were centrifuged at 2,300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The amount of protein was quantified using densitometric measurements for each lane using ImageJ software.

Antibodies against 4E-BP1 (catalog no. 9452), S6K1 (catalog no. 9202), S6K1 Thr(P)-389 (catalog no. 9204), S6 (catalog no. 2217S), and S6 pS235/236 (catalog no. 48565) were purchased from Cell Signaling. Antibodies against ribosomal protein L7 (catalog no. A300-741A, Bethyl), REDD1 (catalog no. 10638-1-AP, Proteintech), α-tubulin (catalog no. T9026, Sigma), and puromycin (clone 12D10) (20) were also used. Rabbit anti-LC3 antibody (NM1) against recombinant rat-LC3B was generated as described previously (21).

In Vivo SUnSET

For in vivo measurements of protein synthesis, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 0.04 μmol/g puromycin exactly 20 min before tissue sampling. Extracted tissues were stored and processed for immunoblot analysis as described elsewhere (22).

Proteasomal Activity Assay

Crude muscle extracts were prepared as described previously (23). To measure the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20 S proteasome, 50 μg pf protein was mixed with an assay buffer containing 100 μm fluorogenic peptide substrate succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Peptide Institute, Inc.) in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mm dithiothreitol. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, hydrolysis of the synthetic peptides was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 460 nm, respectively, using an ARVO MX Plate Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Epoxomicin-sensitive activity was considered to be proteasome-specific.

Measurement of Amino Acid Concentration

Muscle samples were weighed while frozen and homogenized in 5 volumes of ice-cold 5% sulfosalicylic acid. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, free amino acids in the supernatant were measured using an L8500 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Ltd.).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from skeletal muscle using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA was generated with ReverTra Ace (Toyobo) and was analyzed by quantitative real time RT-PCR using the SYBR Green assay (Takara). All data were normalized to GAPDH expression. Sequences of primers used were as follows: Rps6, 5′-ccgccaccggctgtcagaag-3′ and 5′-tccggaccacataacccttccact-3′; Rpl7, 5′-agttatcttccccacgaggtggga-3′ and 5′-tgggtgacaccttagttcatccgtc-3′; and Gapdh, 5′-gccaaggtcatccatgacaact-3′ and 5′-gaggggccatccacagtctt-3′.

Statistical Analysis

All numerical data including error bars represent the mean ± S.E. Statistical comparisons were made using the paired Student's t test.

RESULTS

Muscle Autophagy Is Suppressed by Denervation

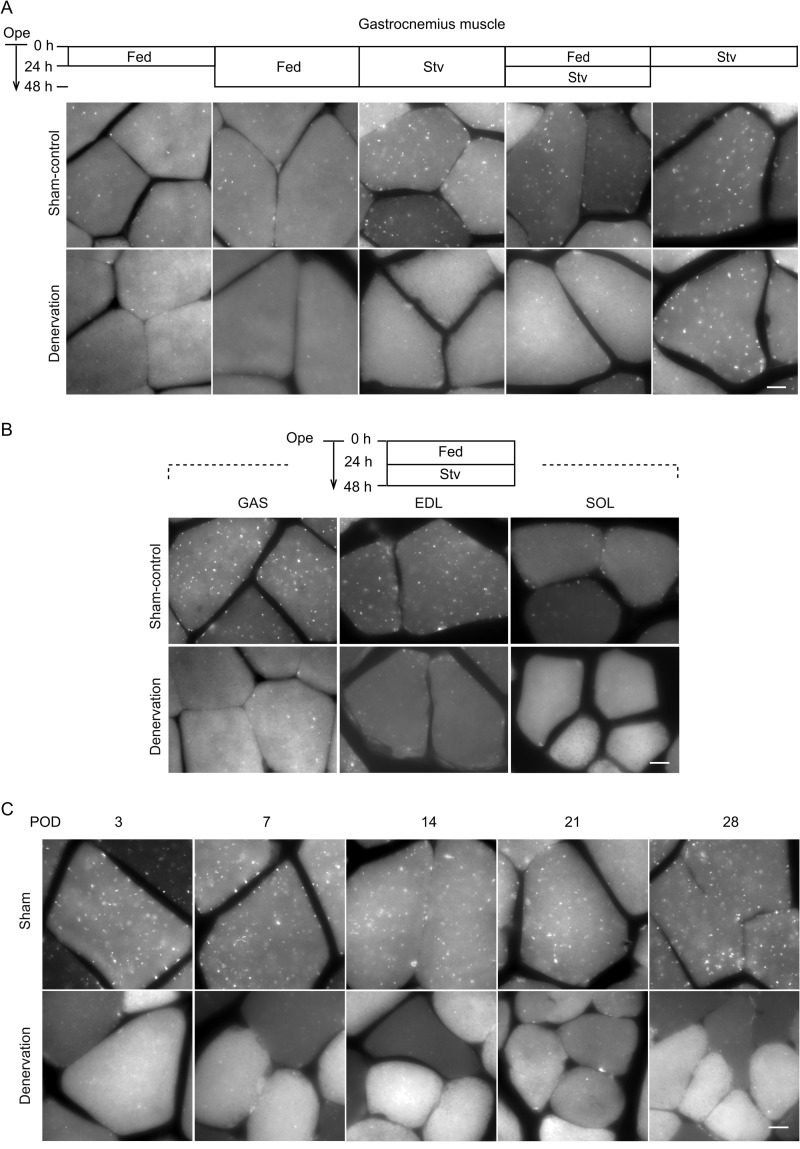

To examine autophagic activity in denervated muscles, sciatic nerve transection was performed on the right side of transgenic mice expressing the autophagosome indicator GFP-LC3. Surgery was also performed on the left side, but the sciatic nerve was left intact, thus serving as an internal control (sham-operated). One or 2 days after this procedure, basal levels of GFP-LC3 puncta representing autophagosomes were observed in sham-operated gastrocnemius (GAS) muscles (mainly consisting of fast twitch fibers). Contrary to our expectations, the number of GFP-LC3 puncta was not increased but rather decreased in denervated muscles (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Muscle autophagy is suppressed by denervation. A, representative images of GFP-LC3 puncta observed in gastrocnemius muscles of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice after denervation (n = 4). Mice were fed (Fed) for 24 or 48 h, starved (Stv) for 48 h, fed for 24 h, and then starved for another 24 h or starved for 24 h after surgery. Scale bar, 10 μm. Ope, time of operation. B, representative images of GFP-LC3 puncta observed in GAS, EDL, and SOL muscles of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice after denervation (n = 5). Mice were fed (Fed) for 24 h and starved (Stv) for another 24 h after surgery. Scale bar, 10 μm. Ope, time of operation. C, representative images of GFP-LC3 dots observed in gastrocnemius muscles of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after denervation. Mice were starved for 24 h before sampling to induce autophagy. Scale bar, 10 μm. POD, post-operative day.

We also tested whether autophagy was also suppressed in denervated muscles under starvation conditions (a known trigger of autophagy). When mice were starved for the entire 48-h period after the operation or for 24 h before sampling, numerous GFP-LC3 puncta were detected in sham-operated muscles; however, there were only a few puncta in denervated muscles (Fig. 1A). Although normal levels of starvation-induced autophagy were observed in denervated muscles at 24 h after denervation, autophagy became suppressed even under starvation conditions from the 2nd day post-denervation (Fig. 1A). Autophagy was also suppressed in denervated extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles (representative of fast twitch muscles) and soleus (SOL) muscles (representative of slow twitch muscles) (Fig. 1B). The suppression of autophagy lasted at least until 1 month after denervation (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that autophagy is generally suppressed in denervated muscles.

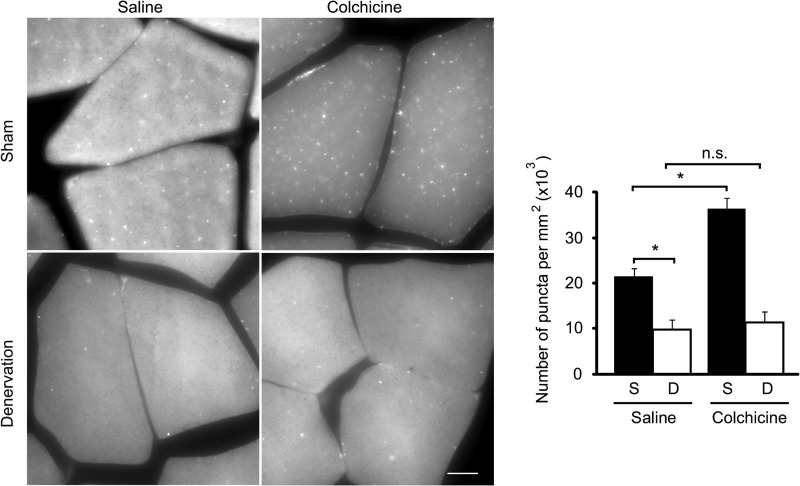

A decrease in the number of the GFP-LC3 puncta in denervated muscles might represent rapid turnover of autophagosomes. To rule out this possibility, we measured the autophagic flux using the microtubule-depolarizing agent colchicine to inhibit consumption of autophagosomes (7). Administration of colchicine increased the number of GFP-LC3 puncta in sham-operated muscles but not in denervated muscles (Fig. 2). This result suggests that the autophagic flux is indeed suppressed in denervated muscles.

FIGURE 2.

Autophagic flux is suppressed in denervated muscles. Representative images and quantification of the GFP-LC3 puncta observed in sham control (S) and denervated (D) gastrocnemius muscles of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice after colchicine treatment. Mice were fed for 24 h and then starved for another 24 h after surgery. Colchicine was intraperitoneally injected (0.4 mg/kg) at 6 h before sampling. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are mean ± S.E. values from 15 photographs obtained from four different animals. *, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

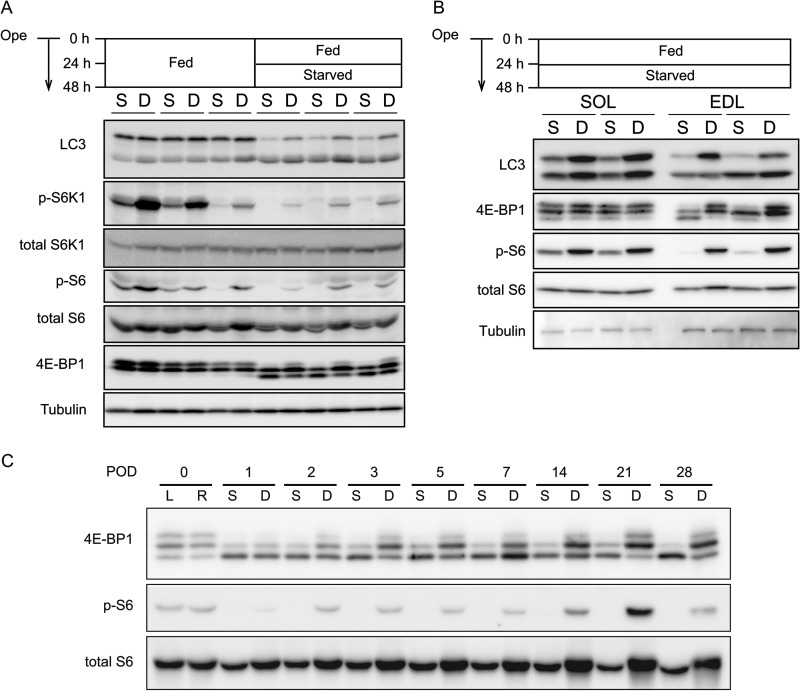

Upon autophagy induction, LC3-I (cytosolic form) is converted to LC3-II (membrane-bound form) as a result of conjugation with phosphatidylethanolamine (21, 24). Denervation caused accumulation of LC3-I under starvation conditions, although the levels of LC3-II were not significantly changed in GAS and EDL muscles (Fig. 3, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S1). In SOL muscles, denervation increased the amount of both LC3-I and II (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S1B), which may reflect transcriptional up-regulation of LC3 (5, 6). The ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I was lower in denervated muscles, suggesting a reduction in the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II. These results are consistent with the fluorescence microscopy data showing that muscle autophagy is suppressed by sciatic nerve transection.

FIGURE 3.

mTORC1 is constitutively activated following denervation. A, representative immunoblot analysis showing the protein levels of LC3 and phosphorylation levels of 4E-BP1, S6, and S6K1 in sham-operated (S) and denervated (D) gastrocnemius muscles. Mice were fed for 48 h or fed for 24 h and then starved for another 24 h after surgery. Ope, time of operation. B, immunoblot analysis was performed as in A using muscle extracts from fast twitch EDL and slow twitch SOL muscles. Mice were fed for 24 h and then starved for the following 24 h after surgery. S, sham control; D, denervation. C, immunoblot analysis showing the phosphorylation levels of 4E-BP1 and S6 in sham-operated and denervated gastrocnemius muscles 1–3, 5, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after operation. Mice were starved for 24 h before sampling. POD, post-operative day; L, left; R, right.

Denervation Induces Constitutive mTORC1 Activation in Muscle

Autophagy can be regulated by a number of factors. Because mTORC1 is a major suppressor of autophagy (25, 26), we investigated whether mTORC1 activity was modulated by denervation. The activity of mTORC1 was assessed by phosphorylation levels of its substrate, S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) (27, 28). Under conditions of feeding ad libitum, phosphorylation of S6K1 and S6 were detected at basal levels and further increased in denervated GAS muscles (Fig. 3A). After starvation for 24 h, S6K1 and S6 were dephosphorylated almost completely in sham controls but were still phosphorylated in denervated GAS muscles (Fig. 3A). The phosphorylation level of eIF4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), another mTORC1 substrate, was also increased in denervated muscles, although the difference was less apparent before starvation.

We further investigated the activity of mTORC1 in EDL and SOL muscles. Under starvation conditions, 4E-BP1 and S6 were phosphorylated in denervated EDL and SOL muscles (more prominent in fast twitch EDL muscles) (Fig. 3B). Moreover, in accord with long term observation of the suppression of autophagy, we observed mTORC1 activation in the muscle at least for 1 month post-denervation (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that mTORC1 is constitutively activated after denervation, which could be the reason why autophagy is suppressed in denervated muscles.

Denervation-induced mTORC1 Activation Is Proteasome-dependent

We next addressed the mechanism underlying denervation-induced mTORC1 activation. mTORC1 can be activated by amino acids and growth factors (27–29). Because denervation up-regulates ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated muscle proteolysis (3, 4), which can generate high levels of amino acids (30), we hypothesized that mTORC1 could be activated by a proteasome-dependent release of amino acids in denervated muscles.

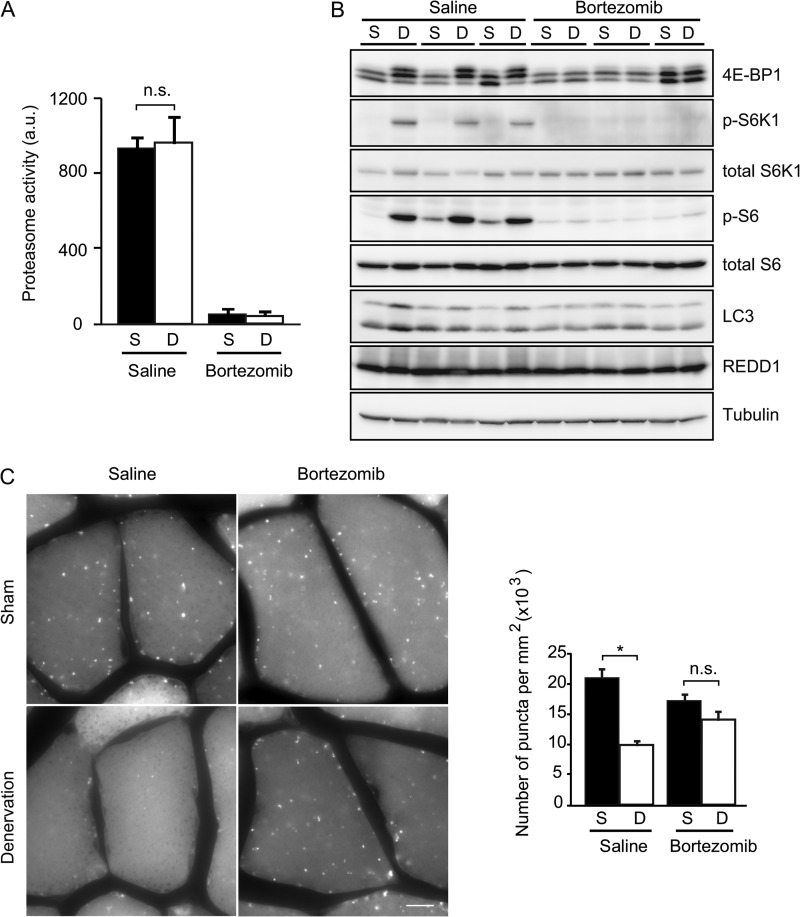

We verified this hypothesis by in vivo administration of bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor (31). Intravenous injection of bortezomib decreased the chymotrypsin-like activity of the muscle proteasome by up to 90% (Fig. 4A) and effectively increased the accumulation of ubiquitin-conjugated proteins in muscle 2.4-fold (supplemental Fig. S2). Because bortezomib treatment also slightly reduced the amount of food intake,3 we starved mice in both the bortezomib-treated and -untreated groups for 24 h before sampling to avoid differences in the nutritional conditions between the two groups. In this setting, phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, S6K1, and S6, which were increased by denervation in saline-treated mice, were profoundly suppressed in bortezomib-treated mice (Fig. 4B). We found virtually no differences in the phosphorylation levels between denervated and sham-operated muscles in bortezomib-treated mice. This result suggests that proteasome activity is required for the activation of mTORC1 in muscle after denervation. It was previously shown that REDD1, an mTORC1 repressor, has a very short half-life (∼5 min) (32), but we did not observe a significant change in the REDD1 level as a result of bortezomib administration (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Denervation-induced mTORC1 activation and autophagy suppression are proteasome-dependent. A, administration of bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, suppresses the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome in sham control and denervated tibialis anterior muscles. Mice were fed for 24 h and starved for the following 24 h after surgery. Bortezomib was intravenously injected at 6 and 30 h after surgery at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Muscle samples were collected at 48 h after surgery. Data are mean ± S.E. n = 3 mice. n.s., not significant. B, representative immunoblot analysis showing the effect of bortezomib administration on mTORC1 activity and protein levels of LC3, p62, and REDD1 in the lateral half of gastrocnemius muscles of the same mouse as used in A. C, representative images and quantification of GFP-LC3 puncta observed in gastrocnemius muscles of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice after treatment as described in A. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are mean ± S.E. values from 15 fluorescence microscopy photographs obtained from three different animals. *, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant. S, sham control; D, denervation (A–C).

Accordingly, administration of bortezomib to GFP-LC3 transgenic mice restored the number of GFP-LC3 puncta in denervated muscles up to a level comparable with that of sham control mice (Fig. 4C). Bortezomib also diminished the differences in the levels of LC3 between sham-operated and denervated muscles (Fig. 4B). Thus, denervation-induced mTORC1 activation and autophagy suppression are proteasome-dependent.

Intracellular Amino Acids Levels Increase in Denervated Muscles

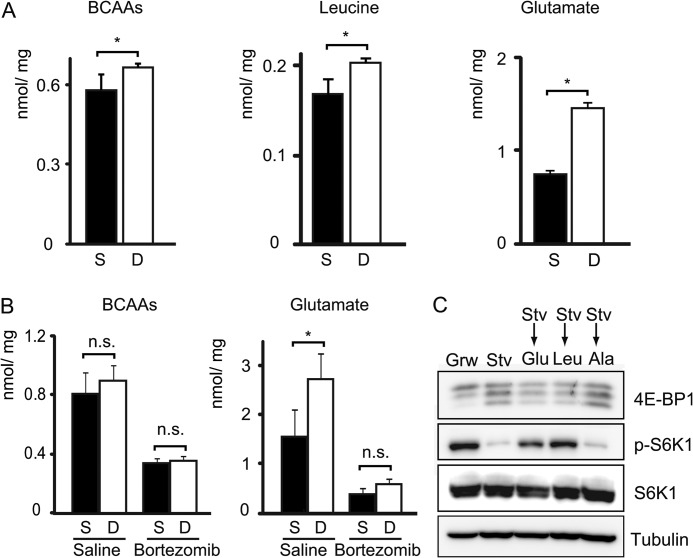

Two days after sciatic nerve transection, intramuscular concentrations of leucine and glutamate were increased by ∼25 and ∼100%, respectively, in mice that were fed (Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. S3A). Levels of some amino acids (e.g. arginine, histidine, lysine, and glutamine) were decreased by an unknown reason. These results are generally consistent with previously reported observations (33, 34).

FIGURE 5.

Amino acids derived from proteasome-mediated proteolysis activate mTORC1 in denervated muscles. A, intramuscular concentration of BCAAs, leucine, and glutamate in sham-operated and denervated gastrocnemius muscles under fed conditions at 48 h after surgery. BCAAs indicate the sum of the concentrations of Leu, Ile, and Val. B, intramuscular concentration of BCAAs and glutamate in the medial half of gastrocnemius muscles of starved mice used in Fig. 3B. C, immunoblot analysis showing the effect of glutamate addition on mTORC1 activity. C2C12 myotubes were subjected to serum and amino acid starvation for 3 h and stimulated with 4× physiological concentrations of glutamate (Glu, 0.44 mm), leucine (Leu, 0.6 mm), and alanine (Ala, 1.64 mm) for 30 min. Grw, growing condition; Stv, starved condition. Tissue amino acid concentrations are expressed as nanomoles/mg of wet weight. Data are mean ± S.E. n = 3 mice. *, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant; S, sham control; D, denervation (A and B).

To verify the role of the proteasome in amino acid production, we measured intramuscular amino acid levels with or without bortezomib treatment. Because of the aforementioned reason, we could only test the effect of bortezomib under starved conditions. We still observed an 80% increase in glutamate in denervated muscles when the mice were starved for 24 h from post-operative day 1 (Fig. 5B). The concentrations of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine were slightly increased by denervation although the changes did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. S3B). In bortezomib-treated mice, the levels of these amino acids were reduced on both sham-operated and denervated sides, and the difference between them was no longer significant (Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. S3B). These data suggest that the proteasome is the cause of the difference in amino acid concentrations between innervated and denervated muscles.

As leucine is a well known stimulator of mTORC1 (27–29, 35), intramuscular elevation of leucine may be a trigger for mTORC1 activation in denervated muscles. In addition, glutamate might stimulate mTORC1. When differentiated C2C12 myotubes were subjected to serum and amino acid starvation for 3 h, 4E-BP1 and S6K1 were dephosphorylated. Re-addition of 0.44 mm glutamate (4× physiological concentration) increased the phosphorylation level of these mTORC1 substrates (Fig. 5C). Although the effect was weaker than that of leucine, this result suggests that glutamate itself can stimulate mTORC1 in starved C2C12 myotubes. Taken together, our data support the hypothesis that amino acids derived from proteasome-mediated proteolysis stimulate mTORC1 in denervated muscles.

mTORC1 Activation Is Essential for Increased Protein Synthesis after Denervation

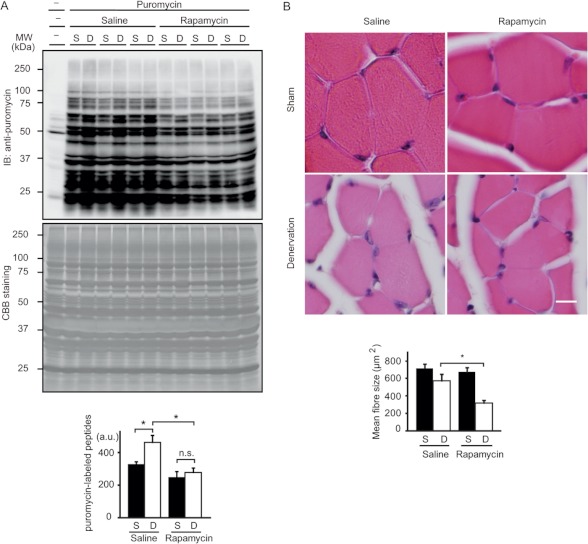

Next, we investigated the physiological significances of mTORC1 activation in denervated muscles. As mTORC1 is the master regulator of protein synthesis, we determined whether protein synthesis is indeed increased in denervated muscles. To this end, we utilized the surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) method, a puromycin-based nonradioactive technique for in vivo measurements of protein synthesis (20, 22). Using this method, we revealed that denervation induced an increase of ∼40% in the amount of puromycin-labeled peptides (Fig. 6A). Daily injection of rapamycin inhibited puromycin incorporation in both innervated and denervated muscles, but the effect was larger in denervated muscles (Fig. 6A), suggesting that protein synthesis was increased in denervated muscles at least partially in an mTORC1-dependent manner.

FIGURE 6.

mTORC1 activation increases protein synthesis in denervated muscles and counteracts denervation-induced atrophy. A, representative immunoblot (IB) analysis revealing the effects of rapamycin treatment on the incorporation of puromycin into nascent polypeptides in the gastrocnemius muscle in surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) analysis 2 days after denervation. Rapamycin (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) was administered 6 h after surgery. Total intensity of puromycin-labeled polypeptides was quantified. Data are mean ± S.E. n = 3 mice. *, p < 0.05, n.s., not significant. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining was shown as the loading control. B, representative cross-sections of sham control and denervated EDL muscles 7 days after denervation with or without daily administration of rapamycin. Scale bar, 10 μm. Mean cross-sectional area of EDL muscle fibers is shown. Data are mean ± S.E. from 300 randomly selected myofibers (n = 3 mice). *, p < 0.05. S, sham control; D, denervation (A and B).

Administration of rapamycin accelerated the atrophy process in denervated muscles. Seven days after denervation, muscle cell size in the vehicle-treated group was decreased by ∼20%. By contrast, daily injection of rapamycin resulted in a greater decrease in muscle fiber size up to ∼40%, suggesting that activated mTORC1 has an anabolic role against denervation-induced muscle atrophy (Fig. 6B).

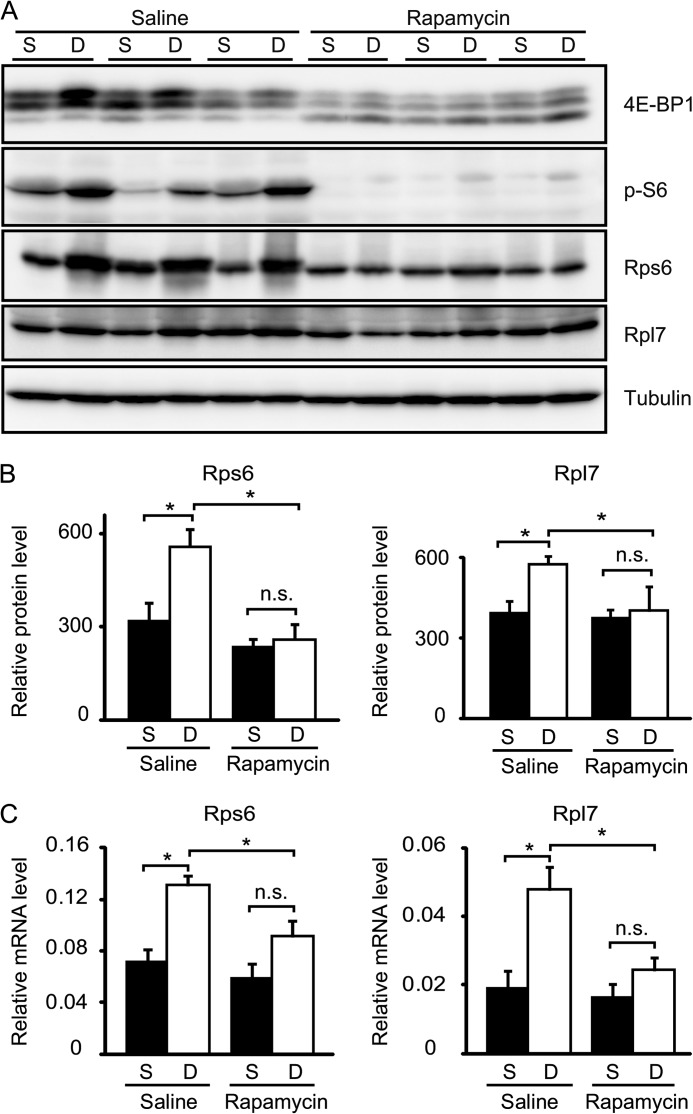

mTORC1 activation can also stimulate ribosome biogenesis through translation of ribosome proteins and transcription of rRNA genes (27, 36). Indeed, it has been reported that transcripts of ribosomal subunits are increased in denervated muscles (2, 37). We confirmed that the amount of ribosomal proteins S6 and L7, members of the 40 S and 60 S ribosomal subunit, were increased by 80 and 50%, respectively, in denervated muscles at 2 days post-operation (Fig. 7, A and B). Real time PCR analysis showed that denervation up-regulated the relative amounts of Rps6 and Rpl7 transcripts by 2- and 2.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 7C). Rapamycin treatment reduced the increase in both protein (Fig. 7B) and mRNA (Fig. 7C) levels of these ribosomal proteins in denervated muscles, suggesting that the activation of mTORC1 increases the expression of ribosomal proteins, probably at both transcriptional and translational steps. Taken together, these data suggest that mTORC1 activation contributes to adaptive metabolic changes in denervated muscles.

FIGURE 7.

mTORC1 activation is required for denervation-induced ribosomal biogenesis in muscle. A, immunoblot analyses showing the effect of rapamycin treatment on mTORC1 signaling and the amount of ribosomal protein S6 (Rps6) and L7 (Rpl7) in gastrocnemius muscles 2 days after denervation. B, protein levels of ribosomal protein S6 (Rps6) and L7 (Rpl7) in A quantified by densitometric analysis. C, quantitative RT-PCR analysis showing the relative abundance of mRNA of ribosomal protein S6 (Rps6) and L7 (Rpl7) in muscle with or without rapamycin treatment for 2 days post-denervation. S, sham control; D, denervation (A–C). Data are mean ± S.E. n = 3 mice. *, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant (B and C).

DISCUSSION

Proteasome-derived Amino Acids Activate mTORC1 and Suppress Autophagy in Denervated Muscles

In this study, we show that autophagy is suppressed in denervated muscles due to constitutive activation of mTORC1 (Fig. 8). This suggests that autophagy has almost no role in the atrophic process following denervation. This is consistent with a previous report that genetic ablation of muscle autophagy does not protect muscle atrophy (8). These authors even observed that autophagy suppression causes more severe atrophy (8). It may be caused by impaired cellular function due to constitutive blockade of intracellular quality control by basal autophagy.

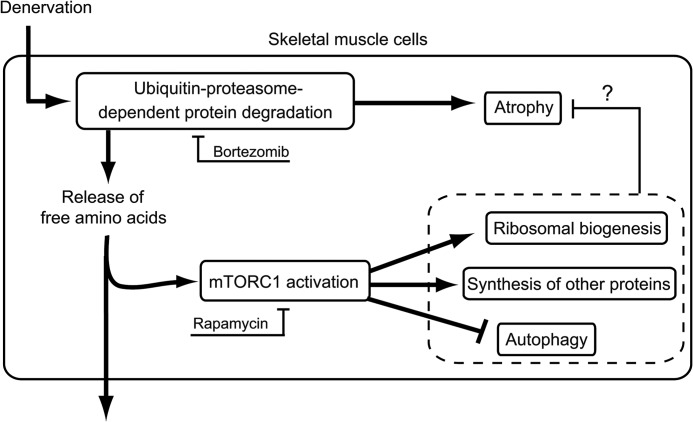

FIGURE 8.

Schematic model illustrating the mechanism and physiological significance of proteasome-dependent activation of mTORC1 following denervation. Denervation up-regulates proteasome-dependent protein degradation, causing the release of free amino acids. These amino acids activate mTORC1, leading to suppression of autophagy, up-regulation of ribosomal biogenesis, and general protein synthesis. This mTORC1-dependent muscle remodeling may be an adaptive response, which counteracts denervation-induced atrophy.

It has been suggested that phosphorylation levels of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, which are indicators of mTORC1 activity, are up-regulated in denervated hindlimb and diaphragm muscles, although the mechanism of this has not been investigated (12–14). From our findings, we propose that the release of amino acids produced by proteasomal proteolysis is the major cause of the constitutive mTORC1 activation (Fig. 8). This positive effect on mTORC1 is very strong, even canceling the negative impact of starvation. Activation of mTORC1 and suppression of autophagy are not observed 1 day after denervation (Figs. 1 and 3). This result suggests that it takes ∼2 days to accumulate intracellular amino acids to a sufficiently high level. We do not completely rule out the possibility that proteasome inhibition suppresses mTORC1 via other pathways. For example, bortezomib may cause accumulation of proteasomal substrate proteins with short half-lives. However, we do not observe such an effect at least on the typical mTORC1 repressor REDD1 (Fig. 4B). Finally, the two inhibitors we used, rapamycin and bortezomib, may not be strictly specific to mTORC1 and the proteasome; these results may need to be confirmed in the future using genetic techniques.

In line with the findings of previous studies, we observed that intramuscular levels of all amino acids were not equally elevated; levels of glutamate and BCAAs tended to increase in denervated muscles (Fig. 5) (33, 34). The elevation of glutamate in denervated muscle might reflect the increase in BCAAs, because BCAAs are extensively catabolized into glutamate and α-keto acids by branched-chain aminotransferase, which is active in skeletal muscle (38–40). It is well known that mTORC1 can be activated by leucine, which may also be the case in denervated muscles. Alternatively, the levels of glutamate, which are considerably increased after denervation, may contribute to mTORC1 activation directly, as suggested above. There may be another indirect mechanism. For example, we observed in denervated muscles a marked increase in the mRNA level of SLC7A5,3 which is an antiporter that exchanges intracellular glutamine and extracellular leucine/essential amino acids and can therefore activate mTORC1 (41). Furthermore, we observed a denervation-induced increase in the level of glutamine synthetase,3 which is the only specific enzyme capable of glutamine synthesis in muscle (42). Based on these data, the increase in glutamate may eventually lead to import of leucine from the extracellular space and mTORC1 activation even under starvation conditions.

mTORC1 Activation Induces Anabolic Responses in Denervated Muscles

It appears that denervation-induced atrophy is not a simple catabolic process. Consistent with mTORC1 activation, we observed that protein synthesis is up-regulated in denervated muscles using the recently developed SUnSET method; this finding supports previously published observations using radioisotope-labeled amino acids (10, 11). Furthermore, it has been shown that denervation increases the mRNA expression of a wide range of genes involved in protein translation such as ribosomal subunits and translation initiation and elongation factors (2, 37, 43). Thus, our study confirms that denervated muscles show both catabolic and anabolic features.

The increased protein synthesis can be at least partially suppressed by rapamycin treatment, suggesting that mTORC1 activation contributes to the anabolic process in denervated muscles. This could be an adaptive response to denervation because rapamycin treatment causes more severe atrophy in denervated muscles compared with innervated muscles (Figs. 6 and 8). However, how mTORC1-dependent protein synthesis produces a beneficial effect in denervated muscle remains unclear. mTORC1 is important for ribosome biogenesis at both transcriptional and translational steps (27, 36). In this study, we have shown that the increase in expression of ribosome subunits depends on mTORC1 (Fig. 7). Ribosome biogenesis may generally support the anabolic responses of denervated muscles. Furthermore, a recent proteomic analysis of denervated tibialis anterior muscles showed that more than 200 proteins are up-regulated at certain time points after denervation (44). These proteins include many metabolic enzymes, structural proteins, and molecular chaperones as well as ribosomal proteins. mTORC1 activation may also contribute to the synthesis of these proteins.

In summary, we found that after denervation, autophagy is suppressed by constitutive activation of mTORC1, which is caused by amino acids derived from proteasomal proteolysis. mTORC1 activation might be an adaptive response to denervation to aid protein synthesis and ribosome biogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuka Hiraoka, Drs. Tsutomu Fujimura, and Takashi Ueno (Laboratory of Proteomics and Biomolecular Science, BioMedical Research Center, Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine) for support with amino acid analysis, and Dr. Shigeo Murata (Laboratory of Protein Metabolism, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Tokyo) for help with the proteasome activity assay.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and by the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers (to N. M.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

P. N. Quy and N. Mizushima, unpublished observations.

- LC3

- microtubule-associated protein light chain 3

- GAS

- gastrocnemius

- EDL

- extensor digitorum longus

- SOL

- soleus

- mTORC1

- mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- S6K1

- S6 kinase 1

- 4E-BP1

- eIF4E-binding protein 1

- SUnSET

- surface sensing of translation

- BCAA

- branched-chain amino acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Glass D. J. (2005) Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy signaling pathways. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 1974–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sacheck J. M., Hyatt J. P., Raffaello A., Jagoe R. T., Roy R. R., Edgerton V. R., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. (2007) Rapid disuse and denervation atrophy involve transcriptional changes similar to those of muscle wasting during systemic diseases. FASEB J. 21, 140–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bodine S. C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V. K., Nunez L., Clarke B. A., Poueymirou W. T., Panaro F. J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z. Q., Valenzuela D. M., DeChiara T. M., Stitt T. N., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. (2001) Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294, 1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomes M. D., Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Navon A., Goldberg A. L. (2001) Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mammucari C., Milan G., Romanello V., Masiero E., Rudolf R., Del Piccolo P., Burden S. J., Di Lisi R., Sandri C., Zhao J., Goldberg A. L., Schiaffino S., Sandri M. (2007) FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 6, 458–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao J., Brault J. J., Schild A., Cao P., Sandri M., Schiaffino S., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. (2007) FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 6, 472–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ju J. S., Varadhachary A. S., Miller S. E., Weihl C. C. (2010) Quantitation of “autophagic flux” in mature skeletal muscle. Autophagy 6, 929–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masiero E., Agatea L., Mammucari C., Blaauw B., Loro E., Komatsu M., Metzger D., Reggiani C., Schiaffino S., Sandri M. (2009) Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 10, 507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furuno K., Goodman M. N., Goldberg A. L. (1990) Role of different proteolytic systems in the degradation of muscle proteins during denervation atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8550–8557 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldspink D. F. (1976) The effects of denervation on protein turnover of rat skeletal muscle. Biochem. J. 156, 71–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Argadine H. M., Hellyer N. J., Mantilla C. B., Zhan W. Z., Sieck G. C. (2009) The effect of denervation on protein synthesis and degradation in adult rat diaphragm muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 107, 438–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hornberger T. A., Hunter R. B., Kandarian S. C., Esser K. A. (2001) Regulation of translation factors during hindlimb unloading and denervation of skeletal muscle in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C179–C187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Machida M., Takeda K., Yokono H., Ikemune S., Taniguchi Y., Kiyosawa H., Takemasa T. (2012) Reduction of ribosome biogenesis with activation of the mTOR pathway in denervated atrophic muscle. J. Cell Physiol. 227, 1569–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Argadine H. M., Mantilla C. B., Zhan W. Z., Sieck G. C. (2011) Intracellular signaling pathways regulating net protein balance following diaphragm muscle denervation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300, C318–C327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bodine S. C., Stitt T. N., Gonzalez M., Kline W. O., Stover G. L., Bauerlein R., Zlotchenko E., Scrimgeour A., Lawrence J. C., Glass D. J., Yancopoulos G. D. (2001) Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bentzinger C. F., Romanino K., Cloëtta D., Lin S., Mascarenhas J. B., Oliveri F., Xia J., Casanova E., Costa C. F., Brink M., Zorzato F., Hall M. N., Rüegg M. A. (2008) Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab. 8, 411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Matsui M., Yoshimori T., Ohsumi Y. (2004) In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1101–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murakami M., Ohkuma M., Nakamura M. (2008) Molecular mechanism of transforming growth factor-β-mediated inhibition of growth arrest and differentiation in a myoblast cell line. Dev. Growth Differ. 50, 121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sadiq F., Hazlerigg D. G., Lomax M. A. (2007) Amino acids and insulin act additively to regulate components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in C2C12 myotubes. BMC Mol. Biol. 8, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmidt E. K., Clavarino G., Ceppi M., Pierre P. (2009) SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat. Methods 6, 275–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Ueno T., Yamamoto A., Kirisako T., Noda T., Kominami E., Ohsumi Y., Yoshimori T. (2000) LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodman C. A., Mabrey D. M., Frey J. W., Miu M. H., Schmidt E. K., Pierre P., Hornberger T. A. (2011) Novel insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis as revealed by a new nonradioactive in vivo technique. FASEB J. 25, 1028–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tanaka K., Ii K., Ichihara A., Waxman L., Goldberg A. L. (1986) A high molecular weight protease in the cytosol of rat liver. 1. Purification, enzymological properties, and tissue distribution. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 15197–15203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kroemer G., Mariño G., Levine B. (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell 40, 280–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mizushima N. (2010) The role of the Atg1-ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. (2006) TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zoncu R., Efeyan A., Sabatini D. M. (2011) mTOR. From growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes, and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 21–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sengupta S., Peterson T. R., Sabatini D. M. (2010) Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol. Cell 40, 310–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koyama S., Hata S., Witt C. C., Ono Y., Lerche S., Ojima K., Chiba T., Doi N., Kitamura F., Tanaka K., Abe K., Witt S. H., Rybin V., Gasch A., Franz T., Labeit S., Sorimachi H. (2008) Muscle RING-finger protein-1 (MuRF1) as a connector of muscle energy metabolism and protein synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 1224–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adams J. (2004) The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell 5, 417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kimball S. R., Do A. N., Kutzler L., Cavener D. R., Jefferson L. S. (2008) Rapid turnover of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) repressor REDD1 and activation of mTORC1 signaling following inhibition of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3465–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davis T. A., Karl I. E. (1988) Resistance of protein and glucose metabolism to insulin in denervated rat muscle. Biochem. J. 254, 667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turinsky J., Long C. L. (1990) Free amino acids in muscle: effect of muscle fiber population and denervation. Am. J. Physiol. 258, E485–E491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dazert E., Hall M. N. (2011) mTOR signaling in disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 744–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayer C., Grummt I. (2006) Ribosome biogenesis and cell growth. mTOR coordinates transcription by all three classes of nuclear RNA polymerases. Oncogene 25, 6384–6391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kostrominova T. Y., Dow D. E., Dennis R. G., Miller R. A., Faulkner J. A. (2005) Comparison of gene expression of 2-mo denervated, 2-mo stimulated-denervated, and control rat skeletal muscles. Physiol. Genomics 22, 227–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang T. W., Goldberg A. L. (1978) Metabolic fates of amino acids and formation of glutamine in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 3685–3693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suryawan A., Hawes J. W., Harris R. A., Shimomura Y., Jenkins A. E., Hutson S. M. (1998) Molecular model of human branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 72–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hutson S. M., Sweatt A. J., LaNoue K. F. (2005) Branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Implications for establishing safe intakes. J. Nutr. 135, 1557S–1564S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nicklin P., Bergman P., Zhang B., Triantafellow E., Wang H., Nyfeler B., Yang H., Hild M., Kung C., Wilson C., Myer V. E., MacKeigan J. P., Porter J. A., Wang Y. K., Cantley L. C., Finan P. M., Murphy L. O. (2009) Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell 136, 521–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. King P. A., Goldstein L., Newsholme E. A. (1983) Glutamine-synthetase activity of muscle in acidosis. Biochem. J. 216, 523–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Batt J., Bain J., Goncalves J., Michalski B., Plant P., Fahnestock M., Woodgett J. (2006) Differential gene expression profiling of short and long term denervated muscle. FASEB J. 20, 115–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun H., Li M., Gong L., Liu M., Ding F., Gu X. (2012) iTRAQ-coupled 2D LC-MS/MS analysis on differentially expressed proteins in denervated tibialis anterior muscle of Rattus norvegicus. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 364, 193–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.