Background: ELMO and DOCK180 synergize to promote Rac-dependent cell migration.

Results: ELMO synergize with a novel interacting protein, ACF7, to promote cytoskeletal changes.

Conclusion: ELMO recruits ACF7 at the membrane and impacts on the microtubule network to increase the persistence of membrane protrusion.

Significance: ELMO controls protrusion stability by acting at the interface between the actin cytoskeleton and the microtubule network.

Keywords: Cell Migration, Cytoskeleton, Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor (GEF), Microtubules, Rho GTPases

Abstract

ELMO and DOCK180 proteins form an evolutionarily conserved module controlling Rac GTPase signaling during cell migration, phagocytosis, and myoblast fusion. Here, we identified the microtubule and actin-binding spectraplakin ACF7 as a novel ELMO-interacting partner. A C-terminal polyproline segment in ELMO and the last spectrin repeat of ACF7 mediate a direct interaction between these proteins. Co-expression of ELMO1 with ACF7 promoted the formation of long membrane protrusions during integrin-mediated cell spreading. Quantification of membrane dynamics established that coupling of ELMO and ACF7 increases the persistence of the protruding activity. Mechanistically, we uncovered a role for ELMO in the recruitment of ACF7 to the membrane to promote microtubule capture and stability. Functionally, these effects of ELMO and ACF7 on cytoskeletal dynamics required the Rac GEF DOCK180. In conclusion, our findings support a role for ELMO in protrusion stability by acting at the interface between the actin cytoskeleton and the microtubule network.

Introduction

Rho GTPases are central proteins controlling cytoskeletal dynamics in a plethora of biological processes including cell motility (1, 2). Guanine exchange factors (GEFs)3 are involved in spatiotemporal activation of Rho proteins and therefore are involved in controlling the coupling of Rho GTPases to specific effectors including kinases and actin nucleators that are principally involved in cytoskeleton remodeling (3). Approximately 85 Rho GEFs have so far been identified in mammals, and they are classified into two subfamilies according to the sequence homology and structural features of their exchange domains: the Dbl and DOCK GEFs (4–6). Among the DOCK GEFs, DOCK180 is a specific activator of Rac GTPases (7, 8).

In Drosophila, the ortholog of DOCK180, MBC (myoblast city), functions downstream of the PDGF/VEGF receptor or muscle fusion receptors to control the activity of Rac during border cell migration and myoblast fusion (9–12). Likewise, the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of DOCK180, Ced-5, controls the engulfment of apoptotic cells and the migration path of the gonad distal tip cells by modulating Rac signaling (13, 14). In a mammalian context, the activation of Rac by DOCK180, via recruitment to the p130Cas-CrkII complex, is regarded as a triggering event for integrin-dependent cell migration (15–17). Recent studies using mouse and cellular models uncovered evolutionarily conserved roles for DOCK180 in mammalian myoblast fusion and engulfment of apoptotic cells (18–20). Further analyses of mice lacking DOCK180 revealed a role for this GEF during the development of the cardiovascular system including a contribution to the migration of endothelial cells through the Sdf1/CXCR4 cytokine/receptor pathway (21). In addition, the close homologs of DOCK180, DOCK2, and DOCK5 play essential roles in cell migration of various blood cell types and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, respectively (22, 23).

ELMO (engulfment and motility) proteins physically engage with DOCK180 to form an evolutionarily conserved complex that regulates Rac biological effects (5, 24–26). ELMO proteins are themselves tightly regulated by autoinhibitory interactions between an ELMO inhibitory domain and ELMO-autoregulatory domain (27). Such closed conformation ELMO remains bound to DOCK180 and prevents promiscuous recruitment of the complex to the membrane. Although the molecular mechanisms involved in releasing the inhibitory intramolecular contacts in ELMO remain to be completely defined, engagement of the Ras-binding domain of ELMO to RhoG and Arl4A GTPases facilitates membrane recruitment of the ELMO-DOCK180 complex and Rac-mediated cytoskeletal changes (27–30).

Biologically, several studies now converge to suggest an evolutionarily conserved function for ELMO-DOCK at the leading edge. In Drosophila, ELMO-MBC is known to activate Rac during border cell migration and dorsal closure (10, 11, 31, 32). In particular, when border cells initiate their collective movement toward the egg chamber, ELMO-MBC activity is required for the leader cell of the cluster to adopt an elongated morphology and, as such, to drive a mesenchymal-like mode of migration (31). In agreement with a role in leading edge establishment, DOCK2-deficient neutrophils fail to orient a migration front when subjected to a migration cue (33). Overexpression and structure/function studies also suggest that ELMO-DOCK can promote the formation of a leading edge in a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-phosphate- and Rac-dependent manner (24, 27, 34–38). Expression of an open conformation and active mutant of ELMO1 is sufficient to promote cell elongation leading to DOCK180-Rac-dependent directed cell motility (27). Conversely, RNAi knockdown of ELMO or DOCK180 impaired leading edge formation in various cellular models (15, 39, 40).

ACF7, also known as MACF1, is a spectraplakin and a +TIP protein that interacts with microtubules and allows their cross-linking to the actin cytoskeleton (41–46). Within the microtubule-binding region of ACF7, a Gas2-related domain and glycine-serine-arginine repeat domain are involved in glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) binding and also serve as substrates for this kinase (44, 46). ACF7 displays a conserved role in membrane protrusion formation during evolution. In Drosophila and mice, respectively, Short Stop and ACF7 regulate filopodia formation and axon extension by regulating the growth of neuronal microtubules (47). ACF7 was recently reported to work downstream of HER2 by promoting microtubule capture in the lamellipodia, and as such, in facilitating the persistence of cell migration (44, 48). Mechanistically, HER2 activation was found to inhibit GSK3β activity at the forming leading edge, inducing local ACF7 desphosphorylation and its subsequent association with microtubules (48). In a similar model, conditional ablation of ACF7 in follicular stem cells disrupted microtubules trajectory, cell polarity, and the efficiency and persistency of migration (44).

Here, we report that ELMO directly interacts with ACF7 to promote persistence in membrane protrusive activity. This interaction contributes to the recruitment of ACF7, where it is involved in microtubule capture and stabilization. We demonstrate that the protrusion formation process by ELMO-ACF7 requires DOCK180 and that active Rac is localized in space and time at the growing protrusions enriched with ELMO and ACF7. This work supports a role for ELMO in protrusion formation by acting at the interface between the actin cytoskeleton and the microtubule network.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies, Cell Culture, and Transfections

A rabbit polyclonal antibody against ELMO1 was previously described (28). An aliquot of a rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing MACF1-ACF7, used in immunofluorescence, was kindly provided by Dr. Ronald Liem (Columbia University). The following reagents were obtained commercially: anti-Myc (9E10), anti-HA (Y-11), anti-DOCK180 (H-70) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); anti-ELMO2 (Novus Biologicals); and anti-GST (GE Healthcare). The anti-GFP magnetic beads immunoprecipitation kit was from Miltenyi Biotec. Anti-β-tubulin antibody was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (The University of Iowa). HEK293T and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (Invitrogen) and transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation method or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using standard procedures. The CHO cell line, subclone LR73, was maintained in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (Invitrogen) and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Nocodazole was from Sigma.

Plasmids and siRNAs

pEGFP-C1A ACF7 and pKH3 ACF7 (isoform 2) were kindly provided by Dr. E. Fuchs (Rockefeller University) and were previously described (43, 44). Raichu-Rac1 was from Dr. M. Matsuda (Kyoto University). The following pcDNA3.1 Myc-ELMO plasmids were previously described: Myc-ELMO1, Myc-ELMO2, Myc-ELMO3, Myc-ELMO11–315, Myc-ELMO1315–727, Myc-ELMO1αN, Myc-ELMO1PxxP, Myc-ELMO1αN/PxxP, and Myc-ELMO1I204D (8, 27, 28). pDsRed-ELMO1 and pDsRed-ELMO1I204D were generated by subcloning BamHI+XhoI fragments from the pcDNA3.1 Myc-ELMO1 and Myc-ELMO1I204D into the same sites of pDsRed-C1. pEBG GST-ACF74700–4945 was generated using human ACF7 as a template. To generate pJG4–5alt ACF74700–4945, a fragment of human ACF74700–4945 was amplified by PCR and cloned in the pJG4–5alt vector. pEG202 LexA-ELMO, LexA-ELMO1–495, and LexA-ELMO315–727 constructs were previously described in Ref. 28. All cloning was verified by DNA sequencing. siRNA against human ELMO2 was generated using the target sequence 5′-gcuaugacuuugucuauca-3′ (Thermo Scientific). siRNA targeting human DOCK180 was generated using the following sequence: 5′-guaccgagguuacacguuauu-3′ (Dharmacon).

Yeast Two-hybrid Screen

The yeast two-hybrid screen that identified ACF7 as a putative ELMO1 interacting protein was conducted by Hybrigenics Services (Paris, France) and was previously described (28). Additional yeast two-hybrid assays were performed exactly as described in Ref. 27.

Immunoprecipitation and GST Fusion Protein Pulldowns

GST fusion protein pulldowns and immunoprecipitation experiments were performed exactly as previously described (35). In some conditions, the cells were incubated in 2 μm nocodazole prior to lysis.

Cell Spreading and Microtubule Stability Assays

CHO LR73 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and subjected to cell morphology analysis as previously described (34). 40,000 cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin (10 μg/cm2) in 4-well LabTek chambers (Falcon). For cell spreading assays, the cells were incubated 45 min before fixing. Immunofluorescence was performed, and Feret's diameters of >50 cells were analyzed using the threshold function of Fiji software (National Institutes of Health) (n = 3 for each condition). In some conditions, 2 μm nocodazole was included during cell spreading. For microtubule depolymerization assays, the cells were allowed to spread for 2 h and then incubated or not on ice for 25 min prior to fixation.

Immunofluorescence

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked in PBS-1% BSA. The cells were incubated with anti-ELMO1, anti-β-tubulin, or anti-HA antibodies (1:200, 1:25 and 1:100 dilution respectively) for 45 min. After three washes in PBS, the cells were incubated with chicken anti-mouse Alexa 488, donkey anti-goat Alexa 568, or goat anti-rabbit Alexa 633 (Invitrogen) (all at 1:1,000 dilutions) for 30 min. After one wash in Tween 0.2% (Sigma) in PBS and three in PBS alone, the chambers slides were mounted with coverslips using a 1:1 PBS-glycerol solution. Fluorescence images were captured with a Zeiss LSM510 or LSM710 confocal microscope, as indicated, and the quantitative cell morphology analysis was performed using images taken with a Leica DM4000 epifluorescence microscope (Deerfield, IL) equipped with a Retiga EXi (QImaging, Burnaby, Canada) camera. In some cases, the microtubule fluorescence images were inverted in photoshop (black to white, white to black) to appreciate the details of the network.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration assays were performed using modified Boyden chambers as previously described (34). The cells were prepared as described above for spreading assays, and 100,000 cells were seeded in 6.5-mm-diameter Transwell inserts with 8-μm pores polycarbonate membranes (Corning, Union City, CA) precoated with fibronectin (90 μg/cm2) on the underside. The cells were allowed to migrate for 4 h prior to fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde. Migratory cells were stained with anti-Myc and anti-mouse Alexa 488 antibodies (1:200 and 1:1,000 dilution, respectively). Fluorescence images of 15 random fields/insert were acquired with a Leica (Deerfield, IL) DM4000 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Retiga EXi (QImaging) camera using a 10× lens. The number of positive cells was counted using the threshold function of Fiji software (National Institutes of Health). Migration was normalized to ACF7 expression, which was quantified by immunofluorescence, and the ELMO1 condition was arbitrarily set at 100%. Expression levels of the exogenous proteins were verified by Western blotting using the remaining cells (not shown). All of the measurements were done in duplicate (n = 3 independent experiments).

Time Lapse Microscopy Assay

To generate time lapse movies of spreading cells, pictures were taken immediately after cell seeding and every minute for 45 min using a LSM710 confocal microscope equipped with environmental control (37 °C, 5% CO2, humidity; Zeiss). The final dimensions of the field of view were 90 × 90 μm. For each of the indicated conditions, more than eight cells were analyzed. Movies were recorded using Fiji software (National Institutes of Health).

Membrane Velocity and Autocorrelation Coefficient Matrix

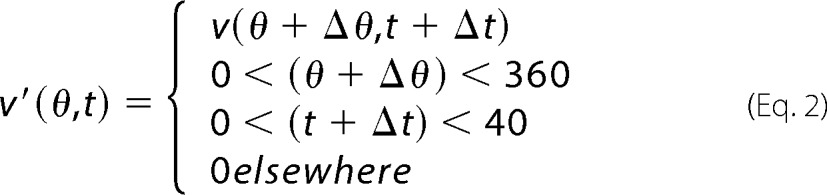

Cell segmentation was performed using the noVel code under Matlab (MathWorks) as described in Ref. 49. Centroids of segmented objects were found and identified as the origin. Objects periphery coordinates r(θ,t) were used to calculate membrane velocity as follows.

|

The coordinate r(θ,t) is the cell periphery distance position at angle θ and time t, relative to the segmented object centroid. Distance positions r(θ) were calculated for each periphery object points. Points closest to a five-degree angle were used to create a velocity map at angles (varying from 0 to 360) and time (from 0 to 40 min). The matrix v′(θ,t) is defined as follows.

|

Membrane velocity was scored into three categories (protruding > 2 μm/10 min; −2 μm/10 min < static < 2 μm/10 min; retracting <−2 μm/10 min) as described in Ref. 50. A minimum of eight cells were analyzed for each condition.

The autocorrelation coefficient matrix R(Δθ,Δt) is calculated from the Pearson correlation coefficient value using the Matlab function corr2 for matrices v(θ,t) and v′(θ,t). Temporal autocorrelation analysis of Δcell periphery = 0 degree from Δtime = 0–40 min in the different conditions was performed. A minimum of eight cells were analyzed for each condition. A color-coded scale of this matrix was generated and is provided in the figure.

FRET Measurements

The cells were transfected with GFP-ACF7, pDsRed-ELMO1I204D, and the Raichu-Rac1 biosensor (51). To map Rac activation, live FRET imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope equipped with a temperature and CO2-controlled chamber (Zeiss). Acquisitions on 15 cells were performed in each independent experiment (n = 3). Donor (CFP), acceptor (YFP), and FRET pictures were taken using identical settings, with the laser power adjusted to the lowest possible (4%) setting to avoid bleaching/phototoxicity. CFP and FRET channels were acquired simultaneously, and YFP images were acquired separately at the same plane of view. For CFP, the excitation source was at 405 nm, and the emission bandpass filter was at 470–500 nm; for YFP, the excitation source was at 514 nm, and the emission bandpass filter was at 530–600 nm (52–54). Only cells expressing moderate levels of CFP and YFP were studied. The FRET efficiency image was generated using the FRET and co-localization analyzer plugin of Fiji (National Institutes of Health) using an equation described in Ref. 55: FRET efficiency(t) = FRET(t) − α*CFP(t)-β*YFP(t), where α and β are the mean of bleed-through coefficients, determined in each run, for both donor and acceptor, respectively. The ratio fluorescence intensity range of FRET efficiency, YFP-Rac, GFP-ACF7, and DsRed-ELMO1I204D expression was displayed using a color spectrum. Positive signals in images typically appear in yellow to red.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences between groups of data were evaluated using the ANOVA test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison procedures (minimum of n = 3).

RESULTS

ACF7 Is a Novel Interacting Partner of ELMO

ELMO proteins are found constitutively bound to DOCK180 and DOCK2–5 GEFs and are important regulators of their signaling activity (5). The mechanism whereby ELMOs cooperate with DOCK180 during Rac-dependent cytoskeleton remodeling is still poorly understood. To further elucidate the contribution of ELMO in regulating cytoskeletal remodeling, we sought to identify novel proteins that could connect ELMO-DOCK180 to regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics. We used ELMO1 as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen against a murine brain cDNA library. Here, we decided to focus our efforts on characterizing the interaction of ELMO with the actin- and microtubule-binding protein ACF7 because of the emerging functions of this spectroplakin in the control of cell motility.

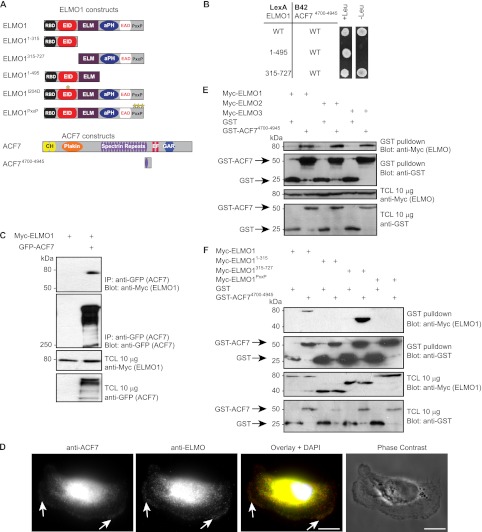

Both clones of ACF7 identified in the yeast two-hybrid screen coded for a protein fragment encompassing amino acids 4700–4945 of ACF7 (isoform 2) corresponding to a region surrounding the 17th spectrin repeat (Fig. 1A). To validate this novel interaction and to reveal the region of ELMO1 involved in ACF7 binding, we conducted a yeast interaction assay using LexA-tagged ELMO1 fragments (wild type and amino acids 1–495 and 315–727) and a B42-tagged ACF4700–4945. As shown in Fig. 1B, both full-length LexA-ELMO1 and LexA-ELMO1315–727, but not LexA-ELMO11–495, allowed for yeast growth in selective conditions when expressed with B42-ACF4700–4945. To further confirm the interaction in the context of full-length proteins, we expressed Myc-ELMO1 with or without GFP-ACF7 and carried out anti-GFP immunoprecipitation. Our results demonstrate that Myc-ELMO1 co-immunoprecipitated with GFP-ACF7, whereas it was not detected in the control anti-GFP immunoprecipitate (Fig. 1C). Unfortunately, none of the commercial antibodies against ACF7 that we tested were capable of immunoprecipitating endogenous or exogenous ACF7. To circumvent this problem, we used a mass spectrometry approach to assay whether endogenous ACF7 can interact with exogenous Myc-ELMO1 expressed at low level in HEK293T cells. We detected endogenous ACF7 bound to both ELMO1 WT and an ELMO1 mutant lacking DOCK180 binding activity (ELMO1αN) (supplemental Fig. S1 and Supplemental Materials and Method). In contrast, ACF7 was not detected in a control Myc IP (supplemental Fig. S1). As a internal control, we detected endogenous DOCK180 bound to Myc-ELMO1 WT but not to ELMO1αN or Myc alone (supplemental Fig. S1). Finally, we investigated the cellular distribution of endogenous ACF7 and ELMO in MDA-MB-231 cells. We found that a pool of ACF7 and ELMO accumulated and co-localized at the cortical membrane (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data support a direct interaction between ELMO1 and ACF7 and point to a region in the C terminus of ELMO1 to contain the ACF7 binding activity.

FIGURE 1.

ELMO proteins directly interact with ACF7. A, schematic representation of ELMO1 and ACF7 constructs used in this study. B, a spectrin repeat of ACF7 interacts with the C terminus of ELMO1. Yeasts transformed with LexA fusion constructs of ELMO1 together with a B42 fusion construct of ACF7 were grown in nonselective (−histidine, −tryptophan) and selective (−histidine, −tryptophan, −leucine) conditions. C, ELMO1 co-immunoprecipitates with ACF7. Lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-GFP (ACF7) antibody. Immunoblots were analyzed with anti-Myc (ELMO1) and anti-GFP (ACF7) antibodies. D, endogenous ACF7 and ELMO co-localize at the cell cortex. MDA-MB-231 cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin. Fixed cells were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing ACF7, a goat polyclonal antibody against ELMO and DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm. E, ACF7 interacts with ELMO proteins. Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with GST alone or GST-ACF74700–4945 together with ELMO1, ELMO2, or ELMO3 were subjected to GST pulldown assays. Immunoblots were analyzed using anti-Myc (ELMO proteins) and anti-GST (GST or GST-ACF74700–4945) antibodies. F, ACF7 interacts with the polyproline region of ELMO1. Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with GST alone or GST-ACF74700–4945 together with ELMO1, ELMO11–315, ELMO1315–727, or ELMO1PxxP were subjected to GST pulldown assays. Immunoblots were analyzed using anti-Myc (ELMO1) and anti-GST (GST or GST-ACF74700–4945) antibodies. TCL, total cell lysate.

Because it is challenging to express, purify, and detect full-length ACF7 (>600 kDa) biochemically, we generated a construct for mammalian cell expression coding for GST-ACF74700–4945, i.e., the fragment harboring the ELMO-binding site, to further characterize the interaction between ACF7 and ELMO proteins. Using this tool, we determined that ACF7 also interacts with ELMO2 and ELMO3 (Fig. 1E). Using a similar pull-down assay, we aimed to define the essential region of ELMO1 implicated in ACF7 binding. We found that GST-ACF74700–4945, but not GST alone, efficiently precipitated the C terminus of ELMO1, Myc-ELMO1315–727 (Fig. 1F). This interaction is specific because an N-terminal fragment of ELMO1, namely Myc-ELMO11–315, did not co-precipitate with GST-ACF74700–4945. Within the C terminus of ELMO1, we previously implicated a α-helix flanking the PH domain as the major DOCK180-binding site (35), and we therefore suspected that the polyproline region might be responsible for interacting with ACF7. Experimentally, we found that full-length Myc-ELMO1 with mutations in this region, Myc-ELMO1PxxP, is impaired in its ability to bind GST-ACF74700–4945 (Fig. 1F). Together, our results demonstrate that ELMO and ACF7 interact directly, using the proline-rich domain of ELMO and a region of ACF7 encompassing the 17th spectrin repeat.

The ELMO-ACF7 Interaction Regulates Membrane Protrusion Dynamics

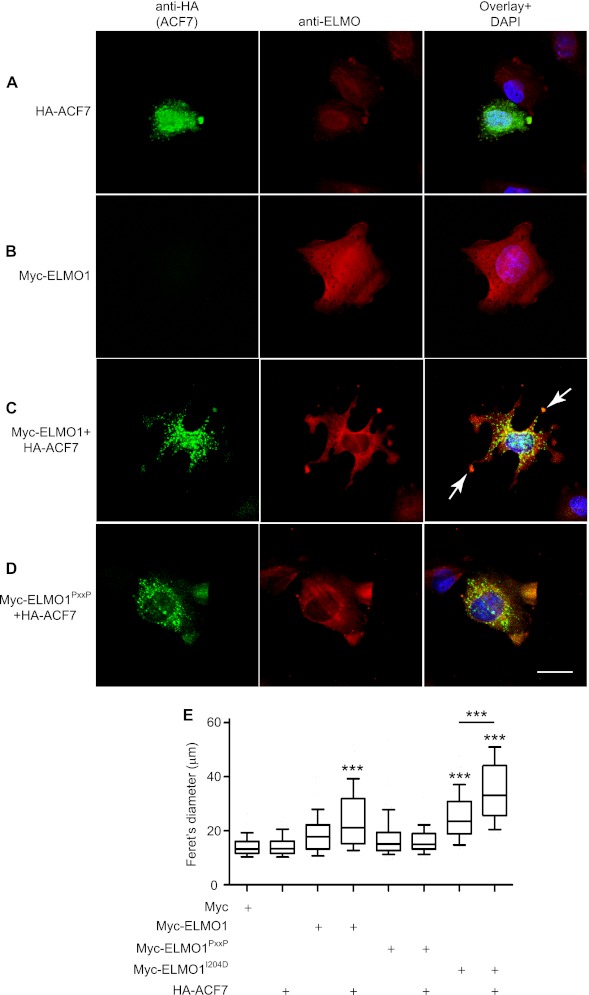

We investigated whether the ELMO1-ACF7 complex can functionally contribute to cytoskeletal rearrangements in a cellular context. CHO LR73 cells have proven to be a good cellular model to dissect the activity of the ELMO-DOCK180 complex (7, 27, 34–36). We found that upon plating of CHO LR73 cells on fibronectin, endogenous ELMO is enriched in discrete membrane areas in control cells expressing an empty vector (data not shown) or in cells expressing HA-ACF7 (Fig. 2A). In this cell type, expression of HA-ACF7 did not affect cell shape, but the protein was found to accumulate at the membrane where it co-localized with endogenous ELMO (Fig. 2A). We could also detect a punctate staining of HA-ACF7 in the cytoplasm of these cells in agreement with its ability to bind the plus end of microtubules (Fig. 2, A, C, and D). As previously observed, exogenous Myc-ELMO1 did not affect cell shape but localized at the membrane similar to the endogenous protein (Fig. 2B). Strikingly, as much as 70% of the cells expressing both Myc-ELMO1 and HA-ACF7 harbored multiple long membrane protrusions upon plating on fibronectin (Fig. 2C, arrows). This increase in membrane protrusion activity is dependent on the formation of a physical complex between ACF7 and ELMO1 because co-expression of HA-ACF7 with Myc-ELMO1PxxP failed to promote morphological changes (Fig. 2D). We previously reported that a conformation mutant of ELMO1 (ELMO1I204D) promotes polarized cell elongation (27). We found that co-expression of HA-ACF7 with Myc-ELMO1I204D increased protrusion elongation (data not shown). To provide a quantitative overview of the effect of overexpression of ELMO1 and ACF7 proteins on cell shape, we measured the Feret's diameter, i.e., the longest distance between any two points of the cell membrane (Fig. 2E). These analyses confirmed that expression of Myc-ELMO1 or Myc-ELMO1I204D with HA-ACF7 and Myc-ELMO1I204D alone promoted cell shape changes (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that ACF7 and ELMO1 synergize to facilitate membrane protrusions during integrin-mediated cell spreading.

FIGURE 2.

ELMO1 and ACF7 cooperate to promote the formation of membrane protrusions. A–D, CHO LR73 cells transfected with: HA-ACF7 (A), Myc-ELMO1 (B), Myc-ELMO1 and HA-ACF7 (C), and Myc-ELMO1PxxP and HA-ACF7 (D). Following serum starvation, the cells were plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 45 min. The cells were stained for ELMO1 (anti-ELMO1) and ACF7 (anti-HA). The arrows indicate membrane protrusions. Scale bar, 10 μm. E, quantification of the effects of the ELMO1-ACF7 interaction on cell elongation. CHO LR73 cells were prepared as in A–D. For each condition, the Feret's diameter of >40 cells were measured. ANOVA tests and Bonferroni's multiple comparison were performed to compare each condition (***, p < 0.001; error bars represent 10–90 percentiles, n = 3).

The ELMO1-ACF7 Complex Temporally Stabilizes Protrusion Elongation to Promote Haptotactic Cell Migration

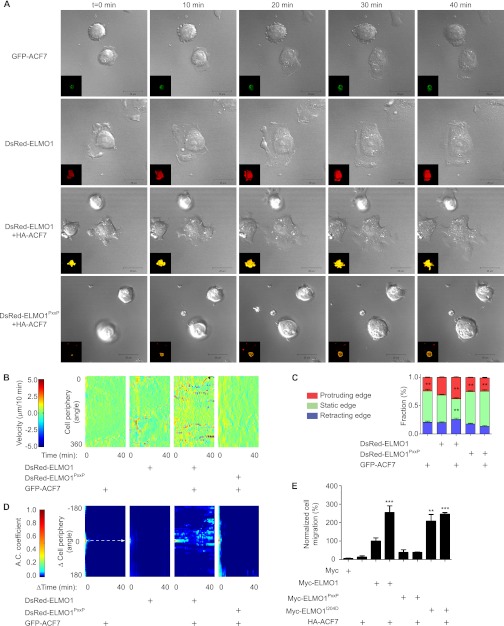

To gain insight on how long membrane protrusions are formed upon co-expression of ACF7 and ELMO1 (as seen in Fig. 2C), we used time lapse microscopy to characterize their dynamics. CHO LR73 cells expressing either GFP-ACF7 or DsRed-ELMO1 alone adhered to fibronectin and spread by sending random cellular protrusions (Fig. 3A and supplemental Videos 1 and 2 for Fig. S3). Co-expression of GFP-ACF7 with DsRed-ELMO1 led to the robust formation of multiple growing protrusions (Fig. 3A and supplemental Video 3 for Fig. S3). In contrast, cells co-expressing GFP-ACF7 with DsRed-ELMO1PxxP adhered on fibronectin but failed to extend long protrusions (Fig. 3A and supplemental Video 4 for Fig. S3). The open conformation mutant DsRed-ELMO1I204D promoted cell elongation (supplemental Fig. S1, including Video 1). Co-expression of GFP-ACF7 with DsRed-ELMO1I204D likewise promoted the formation of polarized membrane protrusions (supplemental Fig. S1, including Video 2).

FIGURE 3.

The ELMO1-ACF7 complex increases the persistence of membrane protrusions. A, live imaging reveals that cells expressing both ELMO1 and ACF7 develop long membrane protrusions. Serum-starved CHO LR73 cells expressing pDsRed-ELMO1 or pDsRed-ELMO1PxxP, with or without pEGFPC1-ACF7, were visualized by live laser-scanning microscopy upon plating on fibronectin-coated plates. A selection of time lapse acquisitions from a representative experiment is shown (see Videos 1 and 4 for supplemental Fig. S3 for the complete video sequences). Inset, overlay of DsRed±GFP. Scale bars, 20 μm. B, expression of ELMO1 and ACF7 increases membrane velocity. Membrane velocity was measured on the representative acquisitions shown in A to derive membrane velocity maps. The pseudocolor scale provides a reference for the membrane velocity across time shown in the maps. C, the membrane velocities determined in B were classified in three categories (protruding, static, or retracting) and quantified for each of the indicated conditions. ANOVA tests and Bonferroni's multiple comparison were performed to compare each category for the different conditions (**, p < 0.01; error bars represent S.E., minimum of eight cells/condition). D, the ACF7-ELMO1 complex increases the persistence of membrane protrusions. Autocorrelation maps for the indicated conditions are shown. The maps were cropped from Δcell periphery (−180 to 180 degree) and from Δtime (0–40 min). The dashed arrow indicates the temporal correlation function at Δcell periphery = 180 °. A pseudocolor scale provides a reference for the autocorrelation coefficient (A.C.). E, the ELMO1-ACF7 interaction promotes cell motility. Migration of CHO LR73 cells, transfected with the indicated plasmids, was evaluated by Transwell migration assays. The ELMO1 condition was arbitrarily set at 100% (**, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001; by ANOVA test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison; error bars represent S.E., n = 3).

To gain quantitative insights on protrusion activity during the different experimental conditions described in Fig. 3A, we used the time lapse videos to measure plasma membrane velocities. From these analyses, we generated membrane velocity maps and a color scale to represent the spatiotemporal membrane velocity (Fig. 3B). Co-expression of GFP-ACF7 and DsRed-ELMO1 increased the plasma membrane velocity, compared with the GFP-ACF7 alone or GFP-ACF7 together with DsRed-ELMO1PxxP conditions (Fig. 3B). These analyses also revealed that cells expressing DsRed-ELMO1 alone had more dynamic protrusions when spreading on fibronectin (Fig. 3B). Expression of DsRed-ELMO1I204D alone or together with GFP-ACF7 promoted dynamic protrusive activity (supplemental Fig. S2).

To more precisely examine the behavior of these protrusions, we classified them in three categories: retracting, static, and protruding as previously done (50). In cells expressing GFP-ACF7, DsRed-ELMO1PxxP or GFP-ACF7 together with DsRed-ELMO1PxxP, the membrane behaviors were very similar (Fig. 3C). Co-expression of GFP-ACF7 with DsRed-ELMO1 significantly increased the formation of protruding membrane area (+11% versus DsRed-ELMO1 alone) at the expense of static membrane edges (−36% versus DsRed-ELMO1 alone) (Fig. 3C).

These results suggested that co-expression of ELMO1 and ACF could increase the duration of membrane extension. To test this, autocorrelation maps of the membrane velocity maps were generated as previously done (50) (Fig. 3D). An increase in the autocorrelation coefficient was observed in the conditions where the cells are expressing GFP-ACF7 together with either DsRed-ELMO1 or DsRed-ELMO1I204D (Fig. 3D and supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, despite the fact that DsRed-ELMO1 can increase membrane velocity (Fig. 3B), no persistence in membrane protrusions was observed by expression of ELMO1 alone (Fig. 3D). We conclude that the ELMO1-ACF7 complex promotes the temporal persistence of membrane protrusions.

We rationalized that persistence in membrane protrusions may favor directional cell migration. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether the ACF7-ELMO1 complex can promote directional cell motility (haptotaxis) in Boyden's chambers. Co-expression of HA-ACF7 with either MycELMO1 or Myc-ELMO1I204D induced a significant increase of 155 and 147%, respectively, in cell migration in comparison with the Myc-ELMO1 condition (Fig. 3E). Expression of Myc-ELMO1PxxP, alone or together with HA-ACF7, failed to promote directed cell movement (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the formation of an ELMO1-ACF7 complex promotes haptotaxis.

ELMO Recruits ACF7 to the Membrane

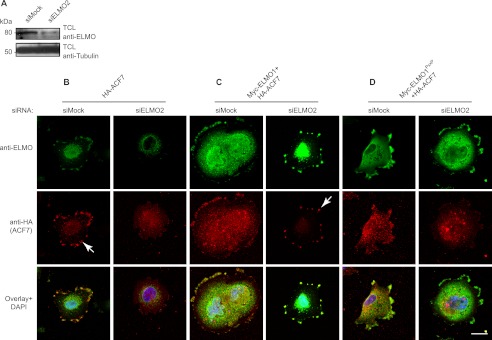

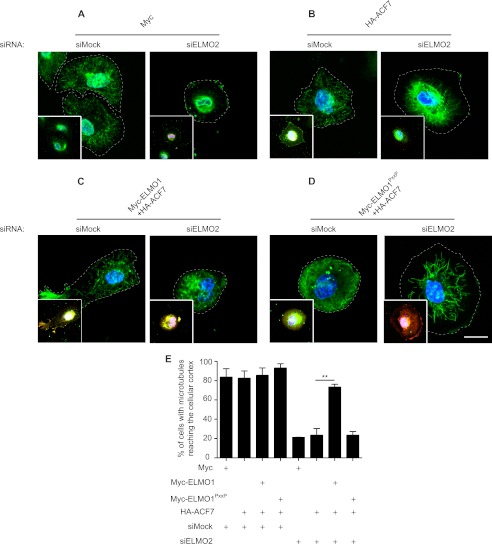

Recruitment of ACF7 at the membrane is important for in situ capture of microtubules and to support directed cell migration (48, 56). We next aimed to gain mechanistic insight on how ELMO and ACF7 are stabilizing membrane protrusions. A function of ELMO could be to localize a pool of ACF7 at the plasma membrane. A siRNA approach to deplete ELMO2 in the MDA-MB-231 human carcinoma cell line was used to test this hypothesis (Fig. 4A). RT-PCR experiments demonstrated that this cell line expresses ELMO2 and not ELMO1 or ELMO3 (supplemental Fig. S3), making it a good cellular model to assay ELMO proteins functions. Likewise, RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that ACF7 is expressed in these cells (data not shown). Following plating on fibronectin, HA-ACF7 localized to the membrane in control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 4B, arrow). In contrast, such a membrane recruitment of HA-ACF7 was completely abolished in ELMO2 siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 4B). We next performed rescue experiments to confirm the importance of ELMO in the recruitment of HA-ACF7 to the membrane. We found that expression of Myc-ELMO1 in ELMO2-depleted cells was sufficient to restore the recruitment of HA-ACF7 at the membrane (Fig. 4C, arrow). In contrast, the rescue of ELMO2 silenced cells by the ACF7-binding deficient ELMO1PxxP mutant failed to relocalize HA-ACF7 to the membrane (Fig. 4D). Although this ELMO-mediated recruitment of ACF7 to the membrane was detectable by immunofluorescence, we were unable to detect ELMO-mediated membrane/cytoskeleton enrichment of ACF7 in biochemical cell fractionation assays (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

ELMO recruits ACF7 to the membrane. A, down-regulation of ELMO2 expression by siRNA was verified by Western blotting. B–D, ELMO2 is required for ACF7 recruitment to the membrane: MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with HA-ACF7 (B), Myc-ELMO1 and HA-ACF7 (C), and Myc-ELMO1PxxP and HA-ACF7 plasmids (D) together with either a siRNA targeting ELMO2 or a nonspecific siRNA were serum-starved. The cells were plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 2 h and stained for ELMO1 (anti-ELMO1 for endogenous or anti-Myc for exogenous ELMO1), ACF7 (anti-HA) and DAPI. The arrows represent recruitment of ACF7 at the membrane. TCL, total cell lysate.

ELMO Is Required for Efficient Microtubule Outgrowth at the Membrane

ACF recruitment at the membrane is required for capture of microtubules downstream of HER2 activation (48). Whether the ACF7-ELMO complex contributes to microtubule capture in MDA-MB-231 cell spreading on fibronectin was tested. In spreading, cells transfected with a control siRNA, microtubules were found to reach the cell cortex (Fig. 5A). In contrast, depletion of ELMO2 by siRNA abolished the capture of microtubules at the cortex (Fig. 5A). Expression of HA-ACF7 alone in ELMO2 depleted cells did not rescue the microtubule capture defect, suggesting that ACF7 must first be recruited by ELMO at the plasma membrane to exert its effect on microtubules (Fig. 5B). Rescue of ELMO2-depleted cells with Myc-ELMO1 restored microtubule capture at the cell cortex (Fig. 5C). However, Myc-ELMO1PxxP failed at rescuing the microtubule defects of ELMO2-depleted cells (Fig. 5D). This phenotype is quantified in Fig. 5E. These results highlight an unexpected role for ELMO in recruiting ACF7 at the membrane to promote efficient microtubule capture in cells spreading on fibronectin.

FIGURE 5.

ELMO2 knockdown impairs microtubule capture at the membrane during integrin-mediated cell spreading. A–D, MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with Myc alone (A), HA-ACF7 (B), Myc-ELMO1 and HA-ACF7 (C), and Myc-ELMO1PxxP and HA-ACF7 plasmids (D) together with either a siRNA targeting ELMO2 or a nonspecific siRNA were serum-starved. The cells were plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 2 h and stained for β-tubulin, Myc, HA, and DAPI. The main panels show the β-tubulin staining, whereas the insets are the overlays of the staining for ELMO1, ACF7, and DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. E, quantification of the percentage of cells with microtubule reaching the cellular cortex in the various conditions (**, p < 0.005; by ANOVA test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison; error bars represent S.E., n = 3).

The ELMO1-ACF7 Interaction and Biological Function Depend on Microtubule Integrity

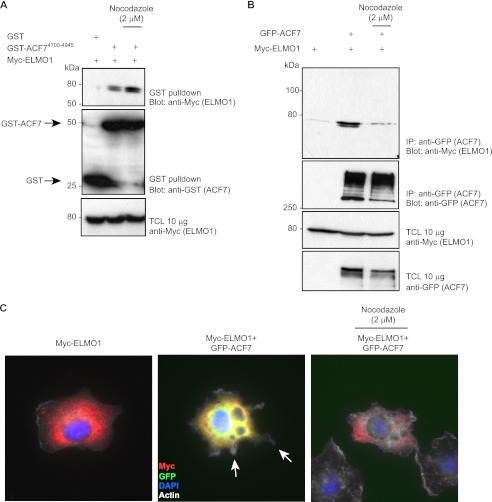

Because ACF7 is a microtubule-binding protein, we investigated whether integrity of the microtubule network is required for efficient ACF7-ELMO1 coupling. First, we found that the isolated ELMO-binding fragment of ACF7, which lacks the microtubule interacting region, can precipitate Myc-ELMO1 in both control condition and when microtubules are disturbed by nocodazole treatment (Fig. 6A). In contrast, we found that an intact microtubule network is necessary for GFP-ACF7-Myc-ELMO1 complex formation (Fig. 6B). Functionally, we investigated whether membrane protrusions elongation induced by co-expression of GFP-ACF7 and Myc-ELMO1 is dependent on the microtubule network. As reported above in Fig. 2, GFP-ACF7-Myc-ELMO1 co-expressing cells formed multiple membrane extensions (Fig. 6C). In contrast, when cells were allowed to spread in the presence of nocodazole, no ACF7-ELMO1 co-expressing cells formed protrusions (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that the ELMO-ACF7 complex forms and functions on microtubules.

FIGURE 6.

Microtubules are required for ELMO1-ACF7 complex formation and function. A, the spectrin 17 region of ACF7 interacts with ELMO1 in a microtubule-independent manner. The cells were treated with 2 μm nocodazole, as indicated, for 30 min. Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with GST alone or GST-ACF74700–4945 together with ELMO1 were subjected to GST pulldown assays. Immunoblots were analyzed using anti-Myc (ELMO proteins) and anti-GST (GST or GST-ACF74700–4945) antibodies. B, microtubule integrity is required for ELMO1-ACF7 coupling. The cells were treated with 2 μm nocodazole for 30 min, as indicated. Lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-GFP (ACF7) antibody. Immunoblots were analyzed with anti-Myc (ELMO1) and anti-GFP (ACF7) antibodies. C, microtubule integrity is essential for GFP-ACF7-Myc-ELMO1-induced membrane protrusions. Following serum starvation, the cells were plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 60 min in the presence or not of 2 μm nocodazole. The cells were stained for ELMO1 (anti-ELMO1) and ACF7 (GFP signal). The arrows indicate membrane protrusions. IP, immunoprecipitation; TCL, total cell lysate.

The ELMO1-ACF7 Interaction Stabilizes Microtubules

Whether the formation of an ACF7-ELMO complex can promote microtubule stability was directly tested. Kodama et al. (42) reported a cold treatment assay to measure microtubule stability in the presence/absence of ACF7. In CHO LR73 cells spreading on fibronectin, we found that microtubules are captured at the cell cortex in all conditions tested (t = 0; Fig. 7A and supplemental Fig. S4). In control cells expressing Myc alone, microtubules completely depolymerized upon incubation on ice (t = 25; supplemental Fig. S4; quantified in Fig. 7B). In cells expressing either Myc-ELMO1, HA-ACF7, Myc-ELMO1PxxP, or Myc-ELMO1I204D, microtubules depolymerized following incubation on ice, although not as completely as in Myc-alone control cells (Fig. 7, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S4). However, co-expression of Myc-ELMO1 with HA-ACF7 protected the cells from cold-induced microtubule depolymerization (Fig. 7, A and B). In contrast, co-expression of HA-ACF7 with Myc-ELMO1PxxP failed to protect against cold-induced microtubule depolymerization (Fig. 7, A and B). Co-expression of HA-ACF7 with Myc-ELMO1I204D promoted microtubule stability upon cold treatment to the same extent as co-expression with Myc-ELMO1 (Fig. 7B and supplemental Fig. S4). We conclude that the ACF7-ELMO complex contributes toward microtubule stability.

FIGURE 7.

The ELMO1-ACF7 interaction stabilizes the microtubule network. A, serum-starved CHO-LR73 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were serum-starved and plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 2 h. Control cells were fixed (t = 0 min), whereas the rest of the cells were subjected to a cold treatment to destabilize microtubules. The cells were stained for β-tubulin, DAPI, ELMO1, and ACF7. Left inset of each panel, overlay of the staining for ELMO1, ACF7, and DAPI to depict transfected cells. Right inset of each panel, magnification of the dashed area. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, quantification of cells with microtubule reaching the cell cortex after cold treatment. >120 cells were analyzed for each condition (***, p < 0.001, by ANOVA and Bonferroni's multiple comparison; error bars represent S.E., n = 3).

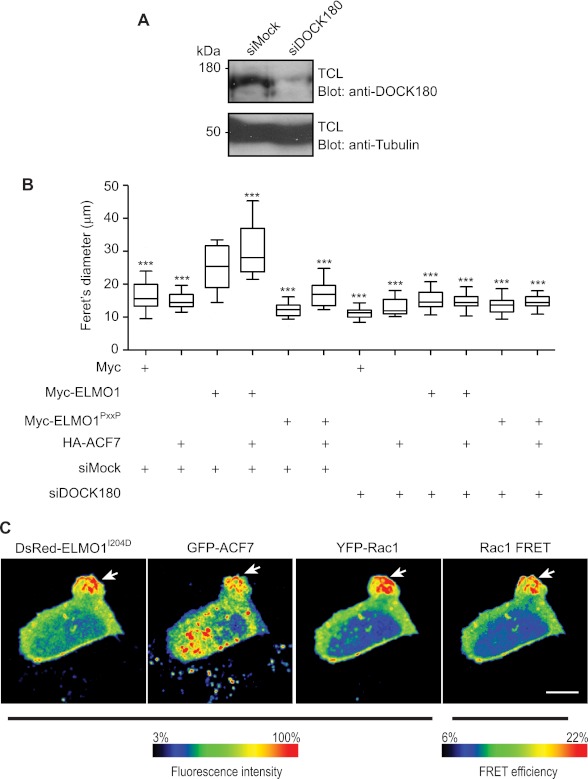

DOCK180 Is Required for Signaling by the ELMO1-ACF7 Complex

ELMO proteins are found in a complex with DOCK GEFs at the basal state. At least two models can be envisioned: (i) ELMO-ACF7 forms an independent module that signals autonomously or (ii) ELMO-DOCK180 complex recruits ACF7 at the membrane to stabilize microtubules, and the DOCK180 GEF activity toward Rac is required at these sites to mediate protrusion elongation. To discriminate between these mechanisms, a siRNA approach was used to knock down DOCK180 in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 8A). Cells treated with the DOCK180 specific siRNA displayed a modest decrease in spreading on fibronectin in comparison with cells expressing a control siRNA, as judged by measuring the cells Feret's diameter (Fig. 8B). As expected, co-expression of HA-ACF7 with Myc-ELMO1 increased cell spreading in control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 8B). In contrast, silencing DOCK180 expression completely blocked the activity of this complex (Fig. 8B). Individual expression of HA-ACF7, Myc-ELMO1, Myc-ELMO1PxxP, or their co-expression with HA-ACF7 in DOCK180-silenced cells failed to enhance cell spreading (Fig. 8B). These results demonstrate that DOCK180 is required downstream of ACF7-ELMO to promote membrane dynamics.

FIGURE 8.

DOCK180 is required for signaling by ELMO1-ACF7. A, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with a control siRNA or a DOCK180-specific siRNA. The knockdown of DOCK180 was verified by Western blotting using a DOCK180-specific antibody. B, ELMO1-ACF7-mediated cell elongation is impaired in DOCK180 knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells. The cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and siRNAs and plated on fibronectin-coated chambers for 2 h. Their morphology was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using anti-ELMO or anti-HA antibodies. For each condition, the Feret's diameter of >40 cells was measured. ANOVA tests and Bonferroni's multiple comparison were performed to compare each condition (***, p < 0.001; error bars represent 10–90 percentiles, n = 3). C, ELMO and ACF7 co-localize with active Rac in membrane protrusions. Serum-starved CHO-LR73 cells transfected with pDsRed-ELMO1I204D, pEGFPC1A-ACF7, and Raichu-Rac1 were imaged using laser-scanning microscopy upon plating on fibronectin-coated plates. The ratio fluorescence intensity range of FRET efficiency is displayed using a color scale. The arrows indicate the area of the cell where the proteins co-localize and the Rac activity is enriched. TCL, total cell lysate.

In support of a model where DOCK180 is acting in concert with ELMO-ACF7, a prediction would be that Rac activity should be higher where ELMO and ACF7 accumulate. We tested whether ELMO1 and ACF7 spatiotemporally co-localized with Rac activation during protrusion establishment; to do this, we co-expressed DsRed-ELMO1I204D that we previously characterized to induced polarized protrusion elongation (27). Using a Raichu-Rac1 FRET approach coupled to DsRed-ELMO1I204D and GFP-ACF7 expression, we mapped the localization of DsRed-ELMO1, GFP-ACF7, YFP-Rac1 (total Rac1), and activated Rac1 (FRET signal) in CHO LR73 cells. Upon examining multiple cells (total of 15 cells/experiment, n = 3), we found that ACF7, ELMO, and the Rac biosensor characteristically co-localize in the protruding membrane area (Fig. 8C). Importantly, Rac activation is also maximal in the membrane area where ACF7 and ELMO1I204D accumulate. These results demonstrate that, in addition to acting as a microtubule capture complex, the ELMO-ACF7 complex coordinates microtubule dynamics with Rac activation via the co-recruitment of DOCK180.

DISCUSSION

Membrane polarization is essential in the establishment of directed cell migration. Typically, high Rac activity at the leading edge sets a positive feedback loop together with PI3K that results in signal amplification and accumulation of both GTP-loaded Rac and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-phosphate at the front of the cell (57, 58). Several studies established that activation of the Rac GTPase by the evolutionarily conserved complex composed of ELMO and DOCK contributes to leading edge formation and consequently to collective or single cell movement (31, 33, 34, 36). The ELMO-DOCK protein complex functions in lamellipodia formation by initiating this critical positive feedback loop through its Rac GEF activity and its phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-phosphate binding activity (33, 34), yet it is now accepted that membrane protrusions are highly dynamic and prone to spontaneous retraction (59). Therefore, formation of a protrusion is not necessarily sufficient to promote sustained and directional cell migration, and it is therefore expected that additional signaling events be required to stabilize the polarized edge (60). One such stabilization signal has been attributed to the microtubule network, and the work presented here suggests that ELMO recruits the actin- and microtubule-binding protein ACF7 at sites of nascent protrusions to promote microtubule capture and stabilization. Our results therefore highlight a novel mechanism whereby membrane protrusions initiated by the ELMO-DOCK180-Rac module can have persistence over time through cross-talk with the microtubule network.

Because of their highly conserved sequence and repetitive organization, little is known on how spectrin repeats achieve specificity in ligand binding (61). Our mapping studies suggest that a fragment of ACF7 encompassing the 17th spectrin repeat acts as a novel ELMO-binding domain. Although no consensus sequence has emerged as a canonical spectrin-binding domain, it was unexpected that the C-terminal polyproline region of ELMO would act as a binding site for ACF7. To our knowledge, this would be the first report of a spectrin repeat interacting with a polyproline motif. Interestingly, we previously identified two regions in ELMO mediating contact to DOCK180: (i) an atypical α-helical extension of the ELMO PH domain providing a high affinity interaction site and (ii) the C-terminal polyproline region of ELMO that allowed for stabilization of the complex in vitro (35). However, mutation of the proline residues in full-length ELMO or a mutation/deletion of the SH3 domain had no deleterious effect on the formation of an ELMO-DOCK180 complex, whereas mutations in the α-helical region fully abrogated the interaction (35, 36). In contrast to these biochemical results, functional migration and spreading assays led to the puzzling conclusion that simultaneous inactivation of both DOCK180-binding sites on ELMO1 was necessary to abrogate the activity of this complex in cells (35, 36). In agreement with these observations, it was noted that Ced-12 lacking its proline-rich region was 40% less efficient at rescuing engulfment defects in comparison with its wild-type counterpart (26). Our findings here that the proline-rich region of ELMO carries ACF7 binding activity explains, at least in part, the previous reports suggesting that the polyproline region of ELMO is likely to recruit additional factors critical for motility and engulfment.

Recent studies uncovered roles for ACF7 in cell migration. In response to a wound-induced migration cue, keratinocytes deficient in ACF7 can initially orchestrate signals such as CDC42 GTP loading and recruitment of PKCζ at the leading edge (42), yet they fail to migrate efficiently because of the transient nature of the polarized membrane, implying an important role for ACF7-mediated microtubule remodeling in the persistence of protrusions (42). Mechanistically, GSK3β constitutively phosphorylates ACF7 to negatively control its microtubule binding activity, whereas signals leading to inhibition of GSK3β, such as migration cues, are in contrast promoting ACF7-microtubule interactions by preventing its phosphorylation (44). Similarly, it was found that activation of HER2 by heregulin, a potent migration signal, inhibits GSK3β via a MEMO-mDia1 complex to facilitate ACF7 recruitment at the membrane, microtubule capture, and cell migration in breast cancer cells (48, 56). Our results add to these mechanisms by providing a novel way of recruiting ACF7 to the membrane through binding of ELMO proteins during integrin-mediated cell spreading. Knockdown of ELMO2 expression in MDA-MB-231 strikingly prevented microtubule capture at the membrane. Our rescue experiments in this system suggest an important role for ELMO-ACF7 in the stabilization of microtubule at the membrane because ELMO1, but not an ELMO1 mutant defective in ACF7 binding, can restore both ACF7 localization and microtubule capture. Our overexpression studies in the context of a cold-induced microtubule depolymerization assay also point to a role for the ELMO-ACF7 complex in microtubule stabilization. Further characterization will be required to identify the mechanism whereby ACF7 becomes competent for microtubule capture when recruited by ELMO at the membrane. Negative regulation of GSK3β activity during integrin-mediated cell spreading, potentially via a mechanism implicating ELMO or DOCK180, would be a logical pathway facilitating the microtubule binding activity of ACF7 in a spatiotemporal manner.

Consistent with this notion, GSK3β was found to interact with members of the DOCK-B family of DOCK GEFs, namely DOCK3 and DOCK4, although the conclusions of these studies are opposite in term of the regulation of GSK3β activity (62, 63). One study highlights that DOCK4 enters in the β-catenin degradation complex via direct interaction with APC, axin, and GSK3β (62). Within this complex, DOCK4 is a substrate of the kinase activity of GSK3β where it mediates Rac activation and contributes to β-catenin release downstream of Wnt-3. In contrast, formation of a DOCK3-GSK3β complex was proposed to repress the kinase activity of GSK3β (63). Functionally, this DOCK3-mediated inhibition of GSK3β controlled the accumulation of nonphosphorylated CRMP-2 that is available to promote microtubule assembly. Further investigations will be important to determine whether DOCK-A GEFs (DOCK180,2,5) interact with and modulate the activity of GSK3β. An attractive model would be that the ELMO-DOCK complex could spatiotemporally promote the simultaneous accumulation of inactive GSK3β and nonphosphorylated ACF7 to set up ideal conditions for microtubule capture and stability at sites of leading edge formation.

Our quantification of membrane protrusions induced by ELMO-ACF7 is in agreement with a role for this complex in the persistence of protrusive activity. We attribute this phenotype to the spatiotemporal capture and stabilization of microtubules by ACF7 through its recruitment at nascent protrusions through a direct interaction with ELMO. Nevertheless, DOCK180 depletion experiments underscore that this Rac GEF is essential for the effect of ELMO-ACF7. The simplest working model would be that upon stabilization of nascent protrusions by ACF7-ELMO, Rac activation by DOCK180 contributes to actin polymerization and remodeling, for example, by activating the Arp2/3 complex. Nevertheless, it is possible that Rac activation also directly impinges on the microtubules network. It has been reported that activated Rac, in part via p21-activated kinase signaling, controls both actin and microtubule dynamics (64). In agreement with such findings, Van Aelst and co-workers (65) previously reported that DOCK7-mediated activation of Rac is critical for stabilization of the neurite that is selected to become an axon. Interestingly, Rac activation by DOCK7 does not regulate the actin cytoskeleton but instead appears to stabilize the microtubule network via an uncharacterized pathway that promotes stathmin/Op18 phosphorylation. Because phosphorylation negatively regulates the microtubule catastrophe activity of stathmins, DOCK7-Rac-mediated phosphorylation of this microtubule regulator provides stabilization of the microtubule network (65). Further investigation is required to determine whether DOCK180-mediated activation of Rac also stabilizes the microtubule network by a complementary pathway targeting stathmins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michiyuki Matsuda (Kyoto University), Dr. Elaine Fuchs (The Rockefeller University), and Dr. Ronald Liem (Columbia University) for the generous gift of reagents. We thank Dr. Javier Di Noia and Stephen Methot (Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal) for the advice on GFP immunoprecipitation. We are grateful to Dr. Dominic Filion for support in Matlab programming. We are indebted to Nathalie Lamarche-Vane (McGill) and Erika R. Geisbrecht for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. David Hipfner and Dominic Meier (Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal) for comments on the work.

This work was supported by Operating Grant 019104 from the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Institute of Health Research Grant MOP 77591 (to J.-F. C.).

This article contains supplemental text, videos, and Figs. S1–S4.

- GEF

- guanine exchange factor

- GSK

- glycogen synthase kinase

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heasman S. J., Ridley A. J. (2008) Mammalian Rho GTPases. New insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 690–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jaffe A. B., Hall A. (2005) Rho GTPases. Biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karnoub A. E., Symons M., Campbell S. L., Der C. J. (2004) Molecular basis for Rho GTPase signaling specificity. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 84, 61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossman K. L., Der C. J., Sondek J. (2005) GEF means go. Turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Côté J. F., Vuori K. (2007) GEF what? Dock180 and related proteins help Rac to polarize cells in new ways. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang J., Zhang Z., Roe S. M., Marshall C. J., Barford D. (2009) Activation of Rho GTPases by DOCK exchange factors is mediated by a nucleotide sensor. Science 325, 1398–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brugnera E., Haney L., Grimsley C., Lu M., Walk S. F., Tosello-Trampont A. C., Macara I. G., Madhani H., Fink G. R., Ravichandran K. S. (2002) Unconventional Rac-GEF activity is mediated through the Dock180-ELMO complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Côté J. F., Vuori K. (2002) Identification of an evolutionarily conserved superfamily of DOCK180-related proteins with guanine nucleotide exchange activity. J. Cell Sci. 115, 4901–4913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Geisbrecht E. R., Haralalka S., Swanson S. K., Florens L., Washburn M. P., Abmayr S. M. (2008) Drosophila ELMO/CED-12 interacts with myoblast city to direct myoblast fusion and ommatidial organization. Dev. Biol. 314, 137–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duchek P., Somogyi K., Jékely G., Beccari S., Rørth P. (2001) Guidance of cell migration by the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor. Cell 107, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Erickson M. R., Galletta B. J., Abmayr S. M. (1997) Drosophila myoblast city encodes a conserved protein that is essential for myoblast fusion, dorsal closure, and cytoskeletal organization. J. Cell Biol. 138, 589–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rushton E., Drysdale R., Abmayr S. M., Michelson A. M., Bate M. (1995) Mutations in a novel gene, myoblast city, provide evidence in support of the founder cell hypothesis for Drosophila muscle development. Development 121, 1979–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu Y. C., Horvitz H. R. (1998) C. elegans phagocytosis and cell-migration protein CED-5 is similar to human DOCK180. Nature 392, 501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reddien P. W., Horvitz H. R. (2000) CED-2/CrkII and CED-10/Rac control phagocytosis and cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith H. W., Marra P., Marshall C. J. (2008) uPAR promotes formation of the p130Cas-Crk complex to activate Rac through DOCK180. J. Cell Biol. 182, 777–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheresh D. A., Leng J., Klemke R. L. (1999) Regulation of cell contraction and membrane ruffling by distinct signals in migratory cells. J. Cell Biol. 146, 1107–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiyokawa E., Hashimoto Y., Kurata T., Sugimura H., Matsuda M. (1998) Evidence that DOCK180 up-regulates signals from the CrkII-p130(Cas) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24479–24484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laurin M., Fradet N., Blangy A., Hall A., Vuori K., Côté J. F. (2008) The atypical Rac activator Dock180 (Dock1) regulates myoblast fusion in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15446–15451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park D., Tosello-Trampont A. C., Elliott M. R., Lu M., Haney L. B., Ma Z., Klibanov A. L., Mandell J. W., Ravichandran K. S. (2007) BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature 450, 430–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pajcini K. V., Pomerantz J. H., Alkan O., Doyonnas R., Blau H. M. (2008) Myoblasts and macrophages share molecular components that contribute to cell-cell fusion. J. Cell Biol. 180, 1005–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanematsu F., Hirashima M., Laurin M., Takii R., Nishikimi A., Kitajima K., Ding G., Noda M., Murata Y., Tanaka Y., Masuko S., Suda T., Meno C., Côté J. F., Nagasawa T., Fukui Y. (2010) DOCK180 is a Rac activator that regulates cardiovascular development by acting downstream of CXCR4. Circ. Res. 107, 1102–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fukui Y., Hashimoto O., Sanui T., Oono T., Koga H., Abe M., Inayoshi A., Noda M., Oike M., Shirai T., Sasazuki T. (2001) Haematopoietic cell-specific CDM family protein DOCK2 is essential for lymphocyte migration. Nature 412, 826–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vives V., Laurin M., Cres G., Larrousse P., Morichaud Z., Noel D., Côté J. F., Blangy A. (2011) The Rac1 exchange factor Dock5 is essential for bone resorption by osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 1099–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gumienny T. L., Brugnera E., Tosello-Trampont A. C., Kinchen J. M., Haney L. B., Nishiwaki K., Walk S. F., Nemergut M. E., Macara I. G., Francis R., Schedl T., Qin Y., Van Aelst L., Hengartner M. O., Ravichandran K. S. (2001) CED-12/ELMO, a novel member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac pathway, is required for phagocytosis and cell migration. Cell 107, 27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu Y. C., Tsai M. C., Cheng L. C., Chou C. J., Weng N. Y. (2001) C. elegans CED-12 acts in the conserved crkII/DOCK180/Rac pathway to control cell migration and cell corpse engulfment. Dev. Cell 1, 491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Z., Caron E., Hartwieg E., Hall A., Horvitz H. R. (2001) The C. elegans PH domain protein CED-12 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization via a Rho/Rac GTPase signaling pathway. Dev. Cell 1, 477–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel M., Margaron Y., Fradet N., Yang Q., Wilkes B., Bouvier M., Hofmann K., Côté J. F. (2010) An evolutionarily conserved autoinhibitory molecular switch in ELMO proteins regulates Rac signaling. Curr. Biol. 20, 2021–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel M., Chiang T. C., Tran V., Lee F. J., Côté J. F. (2011) The Arf family GTPase Arl4A complexes with ELMO proteins to promote actin cytoskeleton remodeling and reveals a versatile Ras-binding domain in the ELMO proteins family. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38969–38979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katoh H., Negishi M. (2003) RhoG activates Rac1 by direct interaction with the Dock180-binding protein Elmo. Nature 424, 461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanawa-Suetsugu K., Kukimoto-Niino M., Mishima-Tsumagari C., Akasaka R., Ohsawa N., Sekine S., Ito T., Tochio N., Koshiba S., Kigawa T., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Nishikimi A., Uruno T., Katakai T., Kinashi T., Kohda D., Fukui Y., Yokoyama S. (2012) Structural basis for mutual relief of the Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor DOCK2 and its partner ELMO1 from their autoinhibited forms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3305–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bianco A., Poukkula M., Cliffe A., Mathieu J., Luque C. M., Fulga T. A., Rørth P. (2007) Two distinct modes of guidance signalling during collective migration of border cells. Nature 448, 362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nolan K. M., Barrett K., Lu Y., Hu K. Q., Vincent S., Settleman J. (1998) Myoblast city, the Drosophila homolog of DOCK180/CED-5, is required in a Rac signaling pathway utilized for multiple developmental processes. Genes Dev. 12, 3337–3342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kunisaki Y., Nishikimi A., Tanaka Y., Takii R., Noda M., Inayoshi A., Watanabe K., Sanematsu F., Sasazuki T., Sasaki T., Fukui Y. (2006) DOCK2 is a Rac activator that regulates motility and polarity during neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Cell Biol. 174, 647–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Côté J. F., Motoyama A. B., Bush J. A., Vuori K. (2005) A novel and evolutionarily conserved PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding domain is necessary for DOCK180 signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Komander D., Patel M., Laurin M., Fradet N., Pelletier A., Barford D., Côté J. F. (2008) An α-helical extension of the ELMO1 pleckstrin homology domain mediates direct interaction to DOCK180 and is critical in Rac signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 4837–4851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grimsley C. M., Kinchen J. M., Tosello-Trampont A. C., Brugnera E., Haney L. B., Lu M., Chen Q., Klingele D., Hengartner M. O., Ravichandran K. S. (2004) Dock180 and ELMO1 proteins cooperate to promote evolutionarily conserved Rac-dependent cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6087–6097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nishikimi A., Fukuhara H., Su W., Hongu T., Takasuga S., Mihara H., Cao Q., Sanematsu F., Kanai M., Hasegawa H., Tanaka Y., Shibasaki M., Kanaho Y., Sasaki T., Frohman M. A., Fukui Y. (2009) Sequential regulation of DOCK2 dynamics by two phospholipids during neutrophil chemotaxis. Science 324, 384–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Côté J. F., Vuori K. (2009) Cell biology. Two lipids that give direction. Science 324, 346–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ho E., Irvine T., Vilk G. J., Lajoie G., Ravichandran K. S., D'Souza S. J., Dagnino L. (2009) Integrin-linked kinase interactions with ELMO2 modulate cell polarity. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 3033–3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ho E., Dagnino L. (2012) Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 492–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karakesisoglou I., Yang Y., Fuchs E. (2000) An epidermal plakin that integrates actin and microtubule networks at cellular junctions. J. Cell Biol. 149, 195–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kodama A., Karakesisoglou I., Wong E., Vaezi A., Fuchs E. (2003) ACF7. An essential integrator of microtubule dynamics. Cell 115, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu X., Kodama A., Fuchs E. (2008) ACF7 regulates cytoskeletal-focal adhesion dynamics and migration and has ATPase activity. Cell 135, 137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wu X., Shen Q. T., Oristian D. S., Lu C. P., Zheng Q., Wang H. W., Fuchs E. (2011) Skin stem cells orchestrate directional migration by regulating microtubule-ACF7 connections through GSK3β. Cell 144, 341–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leung C. L., Sun D., Zheng M., Knowles D. R., Liem R. K. (1999) Microtubule actin cross-linking factor (MACF). A hybrid of dystonin and dystrophin that can interact with the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. J. Cell Biol. 147, 1275–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sun Y., Zhang J., Kraeft S. K., Auclair D., Chang M. S., Liu Y., Sutherland R., Salgia R., Griffin J. D., Ferland L. H., Chen L. B. (1999) Molecular cloning and characterization of human trabeculin-alpha, a giant protein defining a new family of actin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33522–33530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sanchez-Soriano N., Travis M., Dajas-Bailador F., Gonçalves-Pimentel C., Whitmarsh A. J., Prokop A. (2009) Mouse ACF7 and drosophila short stop modulate filopodia formation and microtubule organisation during neuronal growth. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2534–2542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zaoui K., Benseddik K., Daou P., Salaün D., Badache A. (2010) ErbB2 receptor controls microtubule capture by recruiting ACF7 to the plasma membrane of migrating cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18517–18522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dubin-Thaler B. J., Hofman J. M., Cai Y., Xenias H., Spielman I., Shneidman A. V., David L. A., Döbereiner H. G., Wiggins C. H., Sheetz M. P. (2008) Quantification of cell edge velocities and traction forces reveals distinct motility modules during cell spreading. PLoS One 3, e3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parrini M. C., Sadou-Dubourgnoux A., Aoki K., Kunida K., Biondini M., Hatzoglou A., Poullet P., Formstecher E., Yeaman C., Matsuda M., Rossé C., Camonis J. (2011) SH3BP1, an exocyst-associated RhoGAP, inactivates Rac1 at the front to drive cell motility. Mol. Cell 42, 650–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Itoh R. E., Kurokawa K., Ohba Y., Yoshizaki H., Mochizuki N., Matsuda M. (2002) Activation of Rac and Cdc42 video imaged by fluorescent resonance energy transfer-based single-molecule probes in the membrane of living cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6582–6591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mochizuki N., Yamashita S., Kurokawa K., Ohba Y., Nagai T., Miyawaki A., Matsuda M. (2001) Spatio-temporal images of growth-factor-induced activation of Ras and Rap1. Nature 411, 1065–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takaya A., Ohba Y., Kurokawa K., Matsuda M. (2004) RalA activation at nascent lamellipodia of epidermal growth factor-stimulated Cos7 cells and migrating Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2549–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yoshizaki H., Ohba Y., Kurokawa K., Itoh R. E., Nakamura T., Mochizuki N., Nagashima K., Matsuda M. (2003) Activity of Rho-family GTPases during cell division as visualized with FRET-based probes. J. Cell Biol. 162, 223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mitra R. D., Silva C. M., Youvan D. C. (1996) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between blue-emitting and red-shifted excitation derivatives of the green fluorescent protein. Gene 173, 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zaoui K., Honoré S., Isnardon D., Braguer D., Badache A. (2008) Memo-RhoA-mDia1 signaling controls microtubules, the actin network, and adhesion site formation in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 183, 401–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang F., Herzmark P., Weiner O. D., Srinivasan S., Servant G., Bourne H. R. (2002) Lipid products of PI(3)Ks maintain persistent cell polarity and directed motility in neutrophils. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weiner O. D., Neilsen P. O., Prestwich G. D., Kirschner M. W., Cantley L. C., Bourne H. R. (2002) A PtdInsP3- and Rho GTPase-mediated positive feedback loop regulates neutrophil polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poukkula M., Cliffe A., Changede R., Rørth P. (2011) Cell behaviors regulated by guidance cues in collective migration of border cells. J. Cell Biol. 192, 513–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rørth P. (2011) Whence directionality. Guidance mechanisms in solitary and collective cell migration. Dev Cell 20, 9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Djinovic-Carugo K., Gautel M., Ylänne J., Young P. (2002) The spectrin repeat. A structural platform for cytoskeletal protein assemblies. FEBS Lett. 513, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Upadhyay G., Goessling W., North T. E., Xavier R., Zon L. I., Yajnik V. (2008) Molecular association between β-catenin degradation complex and Rac guanine exchange factor DOCK4 is essential for Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Oncogene 27, 5845–5855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Namekata K., Harada C., Guo X., Kimura A., Kittaka D., Watanabe H., Harada T. (2012) Dock3 stimulates axonal outgrowth via GSK-3β-mediated microtubule assembly. J. Neurosci. 32, 264–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wittmann T., Bokoch G. M., Waterman-Storer C. M. (2003) Regulation of leading edge microtubule and actin dynamics downstream of Rac1. J. Cell Biol. 161, 845–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Watabe-Uchida M., John K. A., Janas J. A., Newey S. E., Van Aelst L. (2006) The Rac activator DOCK7 regulates neuronal polarity through local phosphorylation of stathmin/Op18. Neuron 51, 727–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.