Background: Antisense transcription can inhibit complementary strand gene expression.

Results: Multiple mechanisms ensure that adh1 antisense transcripts preferentially accumulate in zinc-limited cells.

Conclusion: Different mechanisms control the ratio of sense and antisense transcripts in response to changes in nutrient levels.

Significance: Alterations in the environment may contribute to the aberrant expression of antisense transcripts in complex diseases.

Keywords: Alcohol Dehydrogenase, Antisense RNA, Gene Silencing, Yeast, Zinc

Abstract

In yeast, Adh1 (alcohol dehydrogenase 1) is an abundant zinc-binding protein that is required for the conversion of acetaldehyde to ethanol. Through transcriptome profiling of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome, we identified a natural antisense transcript at the adh1 locus that is induced in response to zinc limitation. This antisense transcript (adh1AS) shows a reciprocal expression pattern to that of the adh1 mRNA partner. In this study, we show that increased expression of the adh1AS transcript in zinc-limited cells is necessary for the repression of adh1 gene expression and that the increased level of the adh1AS transcript in zinc-limited cells is a result of two mechanisms. At the transcriptional level, the adh1AS transcript is expressed at a high level in zinc-limited cells. In addition to this transcriptional control, adh1AS transcripts preferentially accumulate in zinc-limited cells when the adh1AS transcript is expressed from a constitutive promoter. This secondary mechanism requires the simultaneous expression of adh1. Our studies reveal how multiple mechanisms can synergistically control the ratio of sense to antisense transcripts and highlight a novel mechanism by which adh1 gene expression can be controlled by cellular zinc availability.

Introduction

Cells have evolved a wide variety of mechanisms to precisely control gene expression in response to changes in the environment. This control is often mediated by specific transcription factors that bind to promoter regions and conditionally regulate gene expression (1–3). Alternately, RNA-binding proteins can play a central role in regulating gene expression by altering the stability of target mRNAs in response to environmental signals (4, 5). Although many studies have focused on the regulation of protein-coding genes, recent transcriptome profiling has revealed that many genes that are strongly induced or repressed in response to environmental signals have an antisense counterpart (6–8). Moreover, a growing amount of evidence suggests that these natural antisense transcripts (NATs)2 frequently have a regulatory role in controlling gene expression (9–13).

NATs are defined as a class of RNA that shares sequence complementarity with other RNA transcripts in cells. Most commonly, NATs are transcribed at the same genomic locus as their complementary RNA (14). These cis-NATs typically have perfect pair complementarity with their sense strand counterpart. NATs can also be generated at a different genomic locus from their partner RNA and act in trans to regulate gene expression (15). Despite the fact that all NATs are to some extent complementary to their sense strand target, they can control gene expression in a variety of ways. NATs can directly affect transcription of the sense strand gene by blocking the progression of a sense strand RNA polymerase or by providing a scaffold for histone/DNA-modifying enzymes (11, 12, 16, 17). At a post-transcriptional level, antisense/sense RNA duplexes can affect splicing, editing, stability, or translation of mRNAs (16, 18, 19). Antisense/sense duplexes can also be processed into endogenous siRNAs, which in turn can stimulate RNAi-mediated transcriptional or post-transcriptional gene silencing (20, 21). Although many different mechanisms of antisense-dependent regulation of gene expression have been observed, little is known about how the levels of NATs are regulated.

In our studies to identify genes that are regulated by the essential metal zinc in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, we found that one of the most highly expressed transcripts in zinc-limited cells is an antisense transcript generated at the adh1 (alcohol dehydrogenase 1) gene locus. Conversely, adh1 is the most repressed gene under this condition. Because of the high abundance of the adh1AS transcript in response to zinc limitation, we used the adh1 locus as a tool to study how the levels of NATs are regulated. We found that like other zinc-regulated genes in fission yeast, the adh1AS transcript is regulated at a transcriptional level in response to zinc limitation. In addition to this transcriptional control, we show that when the adh1AS transcript is expressed from a heterologous promoter, adh1AS transcript levels are still regulated by zinc. We propose that fission yeast utilizes at least two mechanisms to precisely adjust the ratio of adh1 sense to antisense transcripts in response to cellular zinc status.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fission Yeast Strains and Medium

The S. pombe strains used in this study are described in supplemental Table 1. Strains were generated using a standard PCR-based gene targeting method (22) with the following exceptions. To create nmt1-adh1, additional homologous sequences were added to the kanMX6 cassette using two-step overlapping PCR. The overlapping PCR product was transformed, and correct integration events were screened by diagnostic PCR. For the nmt1-adh1AS strain, primers were designed such that the adh1AS transcript was fused to the nmt1 transcriptional start site. A zinc-limiting form of Edinburgh minimal medium (ZL-EMM) was generated using pure metal stocks and metal-free flasks and omitting the 1.39 μm zinc supplement typically added to EMM. For the majority of studies, yeast cells were grown to exponential phase at 31 °C in YES medium (yeast extracts with supplements). Cells were then spun down, washed twice with ZL-EMM, and then grown for an additional 16 h in ZL-EMM with or without a 200 μm zinc supplement before harvesting. For studies that used the nmt1 promoter, yeast cells were pregrown in EMM before transfer to ZL-EMM. Slower growing strains were grown for longer periods to obtain zinc deficiency.

Plasmid Construction

The primers used for cloning are listed in supplemental Table 2. A lacZ reporter vector was generated by releasing a BamHI/ApaI fragment that contained the lacZ gene from the Yep353 vector (23). This fragment was subcloned into similar sites in the JK148 vector (24) to create JK-lacZ. Specific reporter constructs were generated by amplifying the promoter regions of adh1, adh4, SPBC1348.06 (vel1), adh1AS, nmt1, and pgk1 by PCR. The PCR primers contained BamHI and EagI (adh4, vel1, nmt1, and pgk1) or BamHI and XbaI (adh1 and adh1AS) restriction sites to facilitate cloning into similar sites in JK-lacZ. To generate pgk1-driven adh1AS constructs, the pgk1 promoter region was PCR-amplified with primers containing PstI and SalI sites. PCR products were digested with PstI and SalI before cloning into similar sites in the Rep3x vector (25). All antisense transgenes were PCR-amplified and digested with BamHI and SmaI before cloning into similar sites in the Rep3x-pgk1 vector. One exception was the adh1AS(1–1025) gene fusion, which was cloned as a BamHI/XhoI fragment into BamHI/SalI-digested Rep3x-pgk1. pAAA was generated by amplifying adh1, inclusive of its promoter and terminator, by PCR. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and PstI before cloning into similar sites in the JK148 vector. padh1PA was generated by amplifying by PCR the adh1 promoter and ORF with primers containing PstI and BamHI sites. PCR products were digested with PstI and BamHI before cloning into similar sites in the JK148 vector to generate JK-adh1prom-ORF. The protein A ORF and adh1 terminator were sequentially introduced into BamHI/XbaI and XbaI/SacII sites, respectively, in the JK-adh1prom-ORF vector by similar methods. pPAN was created by amplifying the adh1 ORF with PCR primers containing SalI and BamHI sites. The PCR product was digested with SalI and BamHI and cloned into similar sites in the Rep3x-pgk1 vector to create Rep3x-PAN. The fragment containing the pgk1 promoter, the adh1 ORF, and the nmt1 terminator was subsequently excised using PstI and EcoRI and cloned into similar sites in the JK148 vector. All plasmids containing a JK148 backbone were digested with NruI before integration at leu1 in yeast. All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing analysis.

RNA Purification and Transcriptome Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using hot acidic phenol. For Northern analysis, 5–7 μg of total RNA was denatured and separated on formaldehyde gels containing 1.5% agarose. RNA was transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized to strand-specific probes. Radiolabeled strand-specific RNA probes were generated from purified PCR products and the MAXIscript T7 kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For semiquantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from cells using standard phenol extraction and then treated with DNase I. 2 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using either Tetro reverse transcriptase (Bioline) or Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following standard protocols. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. 10-Fold serial dilutions of samples were performed to confirm the quantitative nature of the assay. For the array analysis, three replicates were performed using total RNA purified from cells grown for 4 h in LZM supplemented with 3 μm Zn2+ and three replicates in LZM supplemented with 3 mm Zn2+. LZM is a zinc-limiting medium that contains 1 mm EDTA (26). The array analysis, array hybridization, antibody detection, and transcriptome analysis were performed using the HybMap system (27). The tiling arrays contained 60-mer oligonucleotide probes (55-base resolution, 5-base overlap), in both the forward and reverse orientation, that represented the entire S. pombe genome. In HybMap, total RNA is hybridized to a tiling array. Arrays are incubated with a monoclonal antibody (S9.6) that recognizes DNA/RNA hybrids of ∼15 bp, followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to a Cy3 fluorophore, allowing quantification. The S9.6 antibody has negligible sequence specificity and is highly sensitive to mismatches in the DNA/RNA hybrid. More details of HybMap are described in Ref. 27. In this study, data are shown as the normalized zinc-limiting signal/normalized zinc-replete signal.

Protein Purification and Western Analysis

Total protein extracts were obtained using a trichloroacetic acid protein precipitation as described previously (28). Proteins were separated using 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and Western blot analysis was performed using standard procedures. Western blots were incubated with the anti-Adh1 (ab34680, Abcam) and anti-Act1 (ab3280, Abcam) primary antibodies, washed, and then incubated with IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR) and IRDye 680-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR). Signal intensities were analyzed using the Odyssey infrared image system (LI-COR).

ChIP and β-Galactosidase Assays

ChIP was performed as described previously (29) using an anti-RNA polymerase II (phospho-Ser5) antibody (ab5131, Abcam). Immunoprecipitations were repeated five times using different chromatin extracts. A representative sample is shown. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (30), and activity units were calculated as follows: (ΔA420 × 1000)/(min × ml of culture × absorbance of culture at 595 nm).

RESULTS

An Antisense Transcript Is Generated at the adh1 Locus under Zinc-limiting Conditions

To identify genes that are induced in response to zinc limitation, tiling arrays were performed using the HybMap system (see “Experimental Procedures” and Ref. 27). For the array analysis, wild-type cells were grown to exponential phase in LZM containing the metal ion chelator EDTA and 3 μm Zn2+ (without zinc) or 3 mm Zn2+ (with zinc). Comparison of our array data with other published data on gene expression in response to zinc deficiency revealed a significant overlap with known zinc-regulated target genes (data not shown). We also noted that growth in LZM led to increased expression of genes necessary for iron uptake and assimilation. Because EDTA can chelate a variety of divalent metal ions, we generated a new zinc-limiting medium (ZL-EMM) that lacked metal ion chelators (see “Experimental Procedures”). When a wild-type strain was grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM, genes that are specifically induced in response to zinc limitation, including adh4, zrt1, and vel1, were highly induced (data not shown). Because growth in ZL-EMM resulted in the robust regulation of known zinc-regulated genes without the use of metal ion chelators, all further studies were performed using ZL-EMM with or without zinc supplements.

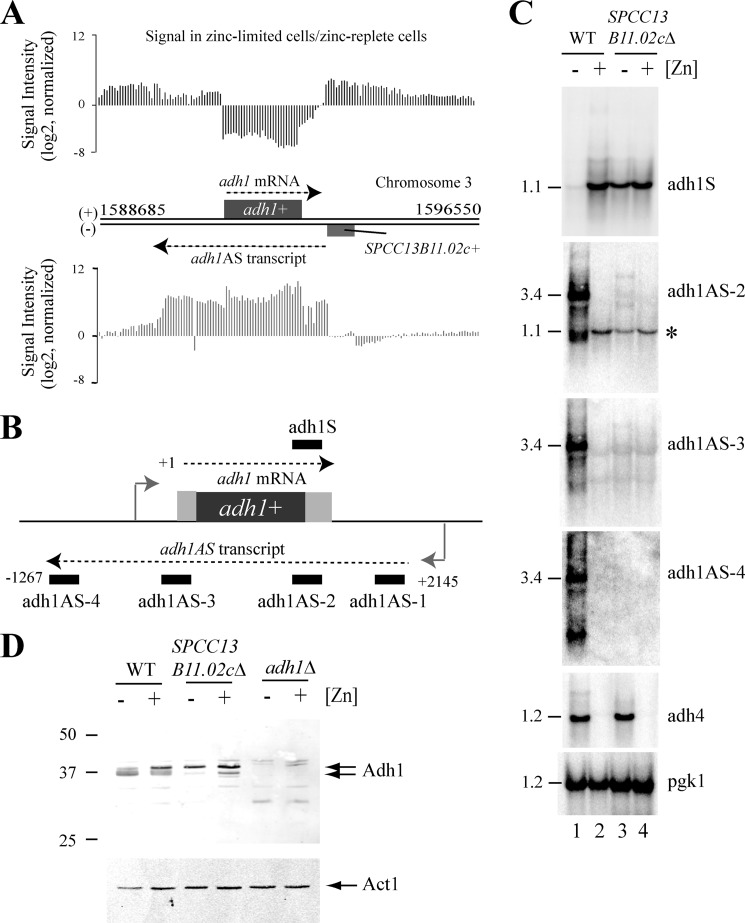

In the array analysis, one of the most repressed genes in response to zinc deficiency was adh1, whereas one of the most highly expressed transcripts under this condition was an antisense transcript at this locus (Fig. 1A). In yeast, Adh1 is an abundant zinc-binding protein that catalyzes the conversion of acetaldehyde to ethanol in the last step of fermentation (31, 32). Because, adh1AS transcript levels were the inverse of the adh1 mRNA, we hypothesized that increased expression of the adh1AS transcript was a mechanism to lower adh1 mRNA levels and that this reduction conserved zinc for other cellular functions.

FIGURE 1.

An antisense transcript is generated at the adh1 locus. A, transcript profile of the adh1 locus on chromosome 3. Individual bars represent the normalized array signal for a given probe. Data are shown on a log 2 scale and as the normalized array signal in zinc-limited cells/normalized array signal in zinc-replete cells. The upper bars represent the normalized array signal obtained for the 5′-strand (+), and the lower bars represent the normalized array signal obtained for the 3′-strand (−). The chromosome position is shown in numbers, and the locations of adh1 and SPCC13B11.02c are indicated by rectangles. B, schematic diagram of the transcripts generated at the adh1 locus. Black rectangles show the positions of strand-specific probes used in Northern blot analysis. C, Northern analysis of total RNA purified from wild-type or SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn). Northern blots were incubated with strand-specific probes that hybridize to the adh1AS transcript or adh1 mRNA. As controls, pgk1 mRNAs levels were determined to confirm equal loading of RNA, and adh4 mRNA levels were measured to ensure that cells grown in ZL-EMM were limited for zinc. Approximate transcript sizes in kilobases are indicated on the left. D, Western analysis of total protein extracts purified from wild-type, SPCC13B11.02cΔ, or adh1Δ cells grown as described for C. Approximate sizes in kilodaltons are shown on the left.

To confirm that an antisense transcript was generated at the adh1 locus, wild-type cells were grown in ZL-EMM with or without a 200 μm zinc supplement, and total RNA was purified for Northern analysis. To examine adh1AS transcript levels, multiple strand-specific probes were generated that hybridized to specific regions of the adh1AS transcript (Fig. 1B, adh1AS-1–4). When the Northern blot was probed with any of the adh1AS probes, a major ∼3.4-kb transcript was detected in zinc-limited cells (Fig. 1C, lane 1). Further 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends Analysis revealed that the major forms of this adh1AS transcript were 3412 and 3348 bp in length and entirely overlapped with the adh1 mRNA (supplemental Fig. 1). When the Northern blot was probed with a strand-specific probe that hybridized to the adh1 mRNA, low levels of adh1 mRNAs were detected in zinc-limited cells, consistent with the regulation seen in the array analysis.

In zinc-replete cells, the inverse regulation was observed. High levels of adh1 mRNAs were detected, and the major adh1AS transcript was not detected. One exception was a single antisense transcript that was comparable in size to the adh1 mRNA (Fig. 1C, adh1AS-2, asterisk). This smaller transcript was not detected by other probes that overlapped with the adh1 gene (Fig. 1C, adh1AS-3) or by strand-specific RT-PCR, suggesting that it was an artifact arising from nonspecific binding of the adh1AS-2 probe to the adh1 mRNA (data not shown). Taken together, the Northern and array analyses indicate that adh1AS transcripts preferentially accumulate in zinc-limited cells, whereas adh1 mRNAs accumulate in zinc-replete cells.

The adh1AS Transcript Is Required for the Zinc-dependent Reduction in adh1 Gene Expression

The inverse relationship between adh1 sense and antisense levels suggested that increased expression of the adh1AS transcript inhibited adh1 gene expression. To test whether expression of the adh1AS transcript was required for repression of adh1 expression, we took advantage of SPCC13B11.02c, an uncharacterized gene that overlaps with the adh1AS promoter region (see Fig. 1A). Because this gene overlapped with the adh1AS promoter, we predicted that SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells would lack important promoter elements necessary for adh1AS transcription. When adh1AS and adh1 transcript levels were examined in SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells, the adh1AS transcript was not detected, and adh1 mRNAs were detected in both zinc-limited and zinc-replete cells (Fig. 1C). A similar result was obtained when a plasmid expressing SPCC13B11.02c was introduced into the SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells, demonstrating that the misregulation of adh1 gene expression was specific to the loss of the adh1AS transcript (data not shown). These results are consistent with the adh1AS transcript being required for the repression of adh1.

To investigate whether the decrease in adh1 mRNA levels in zinc-limited cells also led to reduced levels of the Adh1 protein, Western analysis was performed using crude protein extracts isolated from wild-type, SPCC13B11.02cΔ, and adh1Δ cells that had been grown in ZL-EMM with or without a zinc supplement. When the Western blot was probed with an antibody raised against Saccharomyces cerevisiae Adh1, two major bands were detected that were specific to Adh1 (Fig. 1D, arrows). The smaller band was not regulated by zinc. However, the larger band preferentially accumulated under zinc-replete conditions in wild-type cells and constitutively accumulated in SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells. Thus, changes in adh1AS levels influence the levels of Adh1 protein, suggesting that this mechanism may exist to conserve zinc.

The adh1AS Transcript Is Regulated at a Transcriptional Level in Response to Zinc Limitation

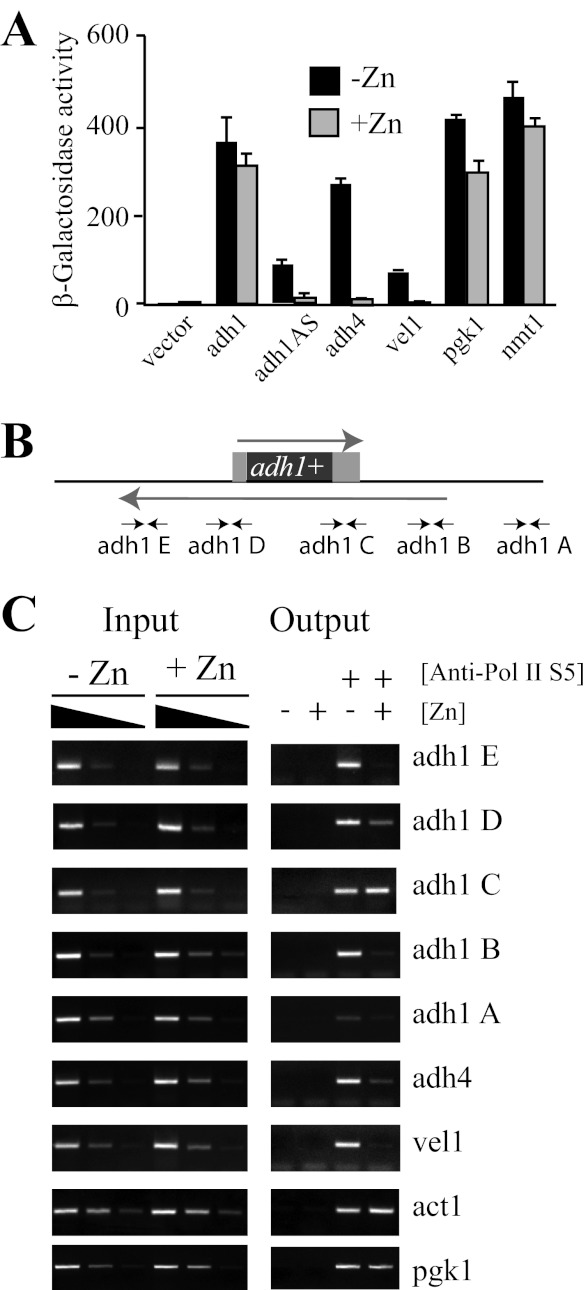

Previous reporter gene studies in S. pombe suggested that increased adh4 expression in zinc-limited cells was a result of increased transcription under this condition (33). To test whether the zinc-dependent changes in adh1AS transcript levels were the result of a transcriptional mechanism, a reporter construct was generated that contained ∼600 nucleotides of the adh1AS promoter fused to the lacZ gene. For controls, lacZ reporter constructs were generated for adh1 (adh1), for genes that are induced in response to zinc deficiency (adh4 and vel1), and for genes that are not regulated by zinc (nmt1 and pgk1). In wild-type cells expressing the adh1AS-lacZ, adh4-lacZ, or vel1-lacZ reporter, β-galactosidase activity was elevated in zinc-limited cells (Fig. 2A). Zinc-dependent regulation of β-galactosidase activity was not observed in cells expressing the nmt1-lacZ, pgk1-lacZ, or adh1-lacZ reporter. The regulation of the adh1AS-lacZ reporter construct by zinc suggests that the adh1AS transcript is regulated at a transcriptional level by zinc.

FIGURE 2.

The adh1AS transcript is regulated by zinc at a transcriptional level. A, wild-type cells containing adh1-lacZ, adh1AS-lacZ, adh4-lacZ, vel1-lacZ, pgk1-lacZ, and nmt1-lacZ reporters were grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn). β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in triplicate by standard procedures. B, schematic diagram of the transcripts generated at the adh1 locus. Arrows indicate the positions at which ChIP primer pairs bind. C, wild-type cells were grown as described for Fig. 1C before cells were harvested, and ChIP was performed using primer pairs that amplified the adh1 locus, other zinc-regulated genes (adh4 and vel1), and constitutively expressed genes (act1 and pgk1). ChIP was performed five times. A representative data set is shown. Anti-Pol II S5, anti-RNA polymerase II (phospho-Ser5) antibody.

As a complementary method of examining the effects of zinc on adh1AS expression, ChIP analysis was performed using antibodies raised against a Ser5-phosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II that is typically associated with an active transcriptional complex (34). For the ChIP analysis, multiple sets of primers were generated that each amplified a specific region of the adh1 locus (Fig. 2B). Primers were also designed to examine RNA polymerase II recruitment to the zinc-regulated adh4 and vel1 genes and the constitutively expressed pgk1 and act1 genes. When Ser5-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II was immunoprecipitated from cross-linked chromatin, genomic regions coding for the adh1AS transcript co-immunoprecipitated in samples from zinc-limited cells (Fig. 2C, adh1 B–E). In contrast, a much smaller genomic region coding for the adh1 mRNA co-immunoprecipitated in samples from zinc-replete cells (Fig. 2C, adh1 C and D). Although ChIP analysis does not provide information relating to which strand is being transcribed, the localization of RNA polymerase II throughout the entire region of the adh1AS transcript in zinc-limited cells and its restricted localization to the adh1 gene in zinc-replete cells are consistent with the adh1AS transcript being preferentially transcribed under zinc-limited conditions.

adh1AS Transcript Levels Are Regulated by Zinc in a Manner That Is Independent of the adh1AS Promoter

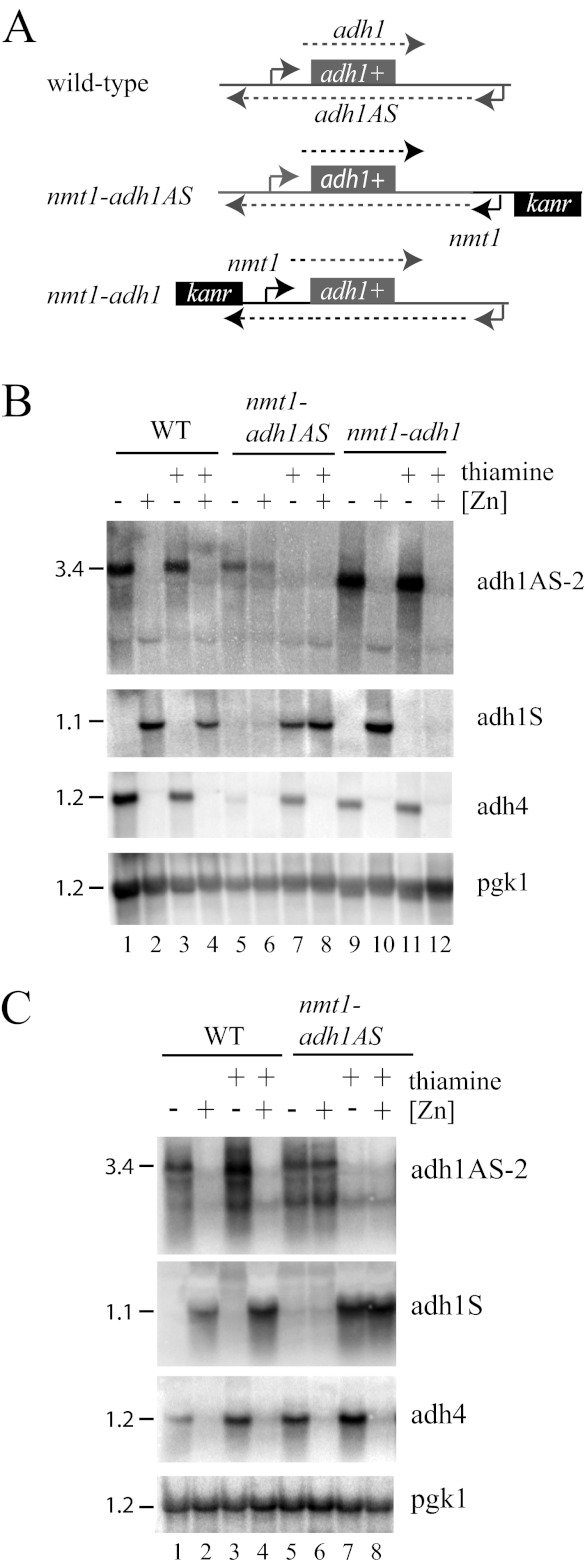

Because the adh1AS transcript was found to be expressed in zinc-limited cells, and adh1 gene expression was reduced under this condition, we hypothesized that the reduction in adh1 gene expression was a direct result of higher transcription of the adh1AS transcript in zinc-limited cells. To test this hypothesis, yeast strains were generated in which the endogenous adh1 or adh1AS promoter was replaced with the nmt1 promoter (Fig. 3A). The nmt1 (no message in thiamine 1) promoter is a conditional promoter that is active in the absence of thiamine and is repressed by the addition of thiamine (35). These strains therefore provided a means of examining the regulation of adh1 transcript levels in a manner that was independent of the endogenous adh1 and adh1AS promoters.

FIGURE 3.

Zinc-dependent regulation of the adh1 transcript is independent of the adh1 promoter. A, schematic diagram of the adh1 locus in wild-type, nmt1-adh1AS, and nmt1-adh1 strains. adh1 sense and antisense transcripts are shown as dashed lines. B and C, Northern analysis of total RNA purified from wild-type, nmt1-adh1AS, and nmt1-adh1 cells grown to exponential phase (B) or stationary phase (C) in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 15 μm thiamine. Blots were probed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

To test how adh1AS and adh1 expression levels influenced the regulation at the adh1 locus, the wild-type, nmt1-adh1AS, and nmt1-adh1 strains were grown under zinc-limiting and zinc-replete conditions in the presence or absence of thiamine, and total RNA was purified for Northern analysis (Fig. 3B). When wild-type cells were grown in the presence or absence of thiamine, adh1AS transcripts accumulated in zinc-limited cells, and adh1 mRNAs accumulated in zinc-replete cells (Fig. 3B, lanes 1–4), indicating that the addition of thiamine did not interfere with general zinc homeostasis. When the nmt1-adh1AS strain was grown in the absence of thiamine, adh1AS transcripts accumulated under both zinc-limiting and zinc-replete conditions, and there was a reduction in adh1 mRNA levels (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6). Although expression from the nmt1 promoter is not regulated by zinc, slightly higher levels of the adh1AS transcript accumulated in zinc-limited cells, suggesting that adh1AS transcript levels might be subject to a second level of regulation. This secondary zinc effect appeared to be limited to exponentially growing cells because adh1AS transcripts accumulated to equal levels under zinc-limiting and zinc-replete conditions when nmt1-adh1AS cells were grown to stationary phase (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6). When nmt1-adh1AS cells were grown to exponential phase in the presence of thiamine, there was a significant decrease in adh1AS transcript levels and a corresponding increase in adh1 mRNAs (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8). Thus, the expression level of the adh1AS transcript directly influences adh1 gene expression.

In the nmt1-adh1 strain, the endogenous adh1 gene is under the control of the nmt1 promoter. The replacement of the endogenous adh1 promoter region with the nmt1 promoter results in the deletion of the 3′-end of the adh1AS transcript (Fig. 3A, nmt1-adh1). In vivo, this replacement led to the production of an abundant shorter antisense transcript that contained both adh1 and nmt1 antisense promoter sequences (Fig. 3B, lanes 9 and 11; and data not shown). Despite this significant change in the adh1AS sequence, this antisense chimera was able to repress adh1 gene expression in zinc-limited cells (Fig. 3B, lane 9). When thiamine was added to nmt1-adh1 cells, there was the expected decrease in adh1 mRNAs. However, there was no change in adh1AS transcript levels. Because alterations in adh1 gene expression had no major effect on adh1AS transcript levels, the data are consistent with the expression level of the adh1AS transcript primarily driving the regulation at the adh1 locus.

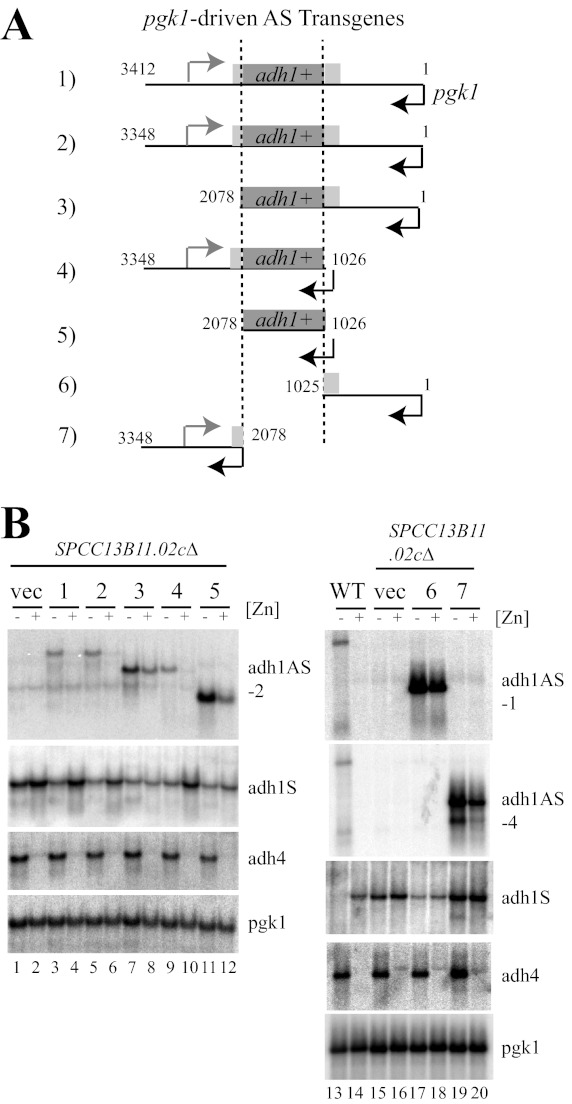

In vivo antisense transcripts can act in cis and/or in trans to inhibit partner strand gene expression (12, 13, 36). To further understand the mechanism by which the adh1AS transcript inhibited adh1 gene expression, we investigated whether the adh1AS transcript could act in trans. For these studies, a plasmid construct (pAS(1–3412)) was generated that expressed the 3.4-kb adh1AS transcript from the pgk1 promoter (Fig. 4A, construct 1). The pgk1 promoter is a constitutive promoter that is not regulated by zinc (Fig. 2A). To distinguish the pgk1-driven adh1AS transgene from the endogenous adh1AS transcript, the pgk1-driven adh1AS transgene was introduced into SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells (a strain in which the native adh1AS transcript is not produced). Surprisingly, in this strain background, the pgk1-driven adh1AS transcript accumulated in low zinc, but not in high zinc (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 3 and 4). A similar result was observed with an integrated version of pAS(1–3412), suggesting that the reduction in adh1AS levels was not a result of an altered plasmid copy number (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of adh1AS transgenes by zinc. A, schematic diagram of the pgk1-driven adh1AS (AS) transgenes. The start and end points of each transgene is shown in nucleotides. B, Northern blot analysis of total RNA purified from a WT control or SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells expressing each of the transgenes or the empty vector (vec). Cells were grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn). Blots were probed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

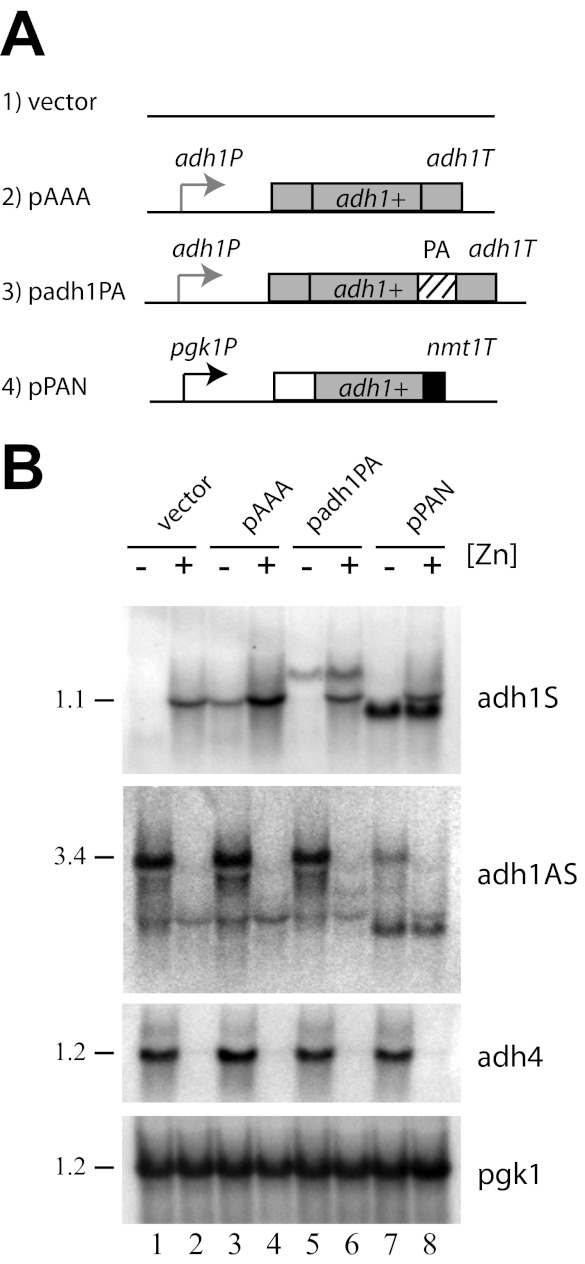

The regulation of the pgk1-driven adh1AS transcript levels by zinc was consistent with the previous results suggesting that a secondary mechanism might contribute to the overall regulation of adh1AS transcript levels by zinc. Alternately, the introduction of a second copy of the antisense transcript into a cell may have promoted RNAi- or antisense-dependent gene silencing (12, 37). To investigate why adh1AS transcript levels were regulated by zinc when expressed in trans, we tested whether the introduction of a second copy of the adh1 gene could trigger zinc-dependent changes in adh1 sense or antisense levels. For these studies, new constructs were generated in which adh1 or protein A-tagged adh1 was expressed from its own promoter and terminator (pAAA and padh1PA, respectively) (Fig. 5A). The introduction of the protein A epitope tag created a longer transcript that could be easily distinguished from the endogenous adh1 mRNA. A construct was also generated in which the adh1 ORF was placed under the control of the pgk1 promoter (pPAN). This construct contained the short nmt1 3′-untranslated region, which resulted in a slightly smaller adh1 transcript. All constructs lacked the adh1AS transcript promoter, preventing the expression of the full-length adh1AS transcript. When wild-type cells expressing pAAA or pPAN were grown under zinc-limited and zinc-replete conditions, adh1 mRNAs derived from each of the constructs accumulated under all conditions (Fig. 5B). In wild-type cells expressing padh1PA, a modest decrease in adh1PA transcript levels was observed in zinc-limited cells. However, this decrease was not reproduced in independent experiments. Thus, the zinc-dependent changes in gene regulation were specific to adh1AS transgene constructs and not adh1 transgenes.

FIGURE 5.

Regulation of adh1 transgenes. A, schematic diagram of adh1 transgenes. adh1P and pgk1p indicate use of the adh1 and pgk1 promoters, respectively. adh1T and nmt1T indicate use of the adh1 and nmt1 terminators, respectively. PA represents a protein A epitope tag. B, Northern blot analysis of total RNA purified from wild-type cells expressing each of the transgenes. Cells were grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn). Blots were probed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

Regulation of the adh1AS Transgene Requires the Simultaneous Expression of adh1

To determine whether the zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS transcript levels could be mapped to a specific region of the adh1AS transcript, truncated derivatives of pAS(1–3412) were introduced into SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells, and the levels of adh1 mRNA and antisense transcripts were examined by Northern analysis (Fig. 4, A and B). Robust zinc-dependent regulation of adh1 antisense levels required that the adh1AS transgene contain sequences that overlapped the adh1 promoter region and adh1 ORF (Fig. 4B, constructs 1, 2, and 4). Zinc-dependent regulation was also apparent (but reduced) in strains containing transgenes that overlapped with adh1, but not with the adh1 promoter (Fig. 4B, constructs 3 and 5). Low levels of zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS levels were observed with smaller transgenes that had no overlap with the adh1 open reading frame (Fig. 4B, constructs 6 and 7). When there was direct overlap between the adh1AS transgene and the adh1 mRNA, the levels of the adh1 mRNAs were, for the most part, reciprocal to those of complementary adh1AS transgenes, i.e. when there were high levels of adh1AS transgenes, there were lower levels of adh1 mRNAs.

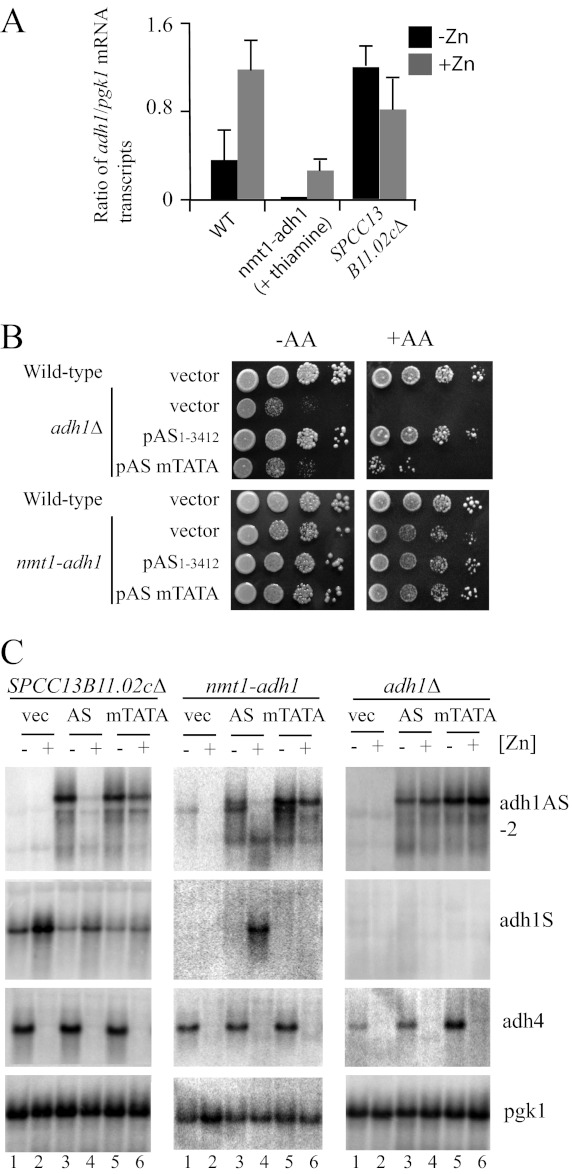

Because maximal zinc-responsive regulation of adh1AS transcript levels was observed with transgenes that were complementary to the adh1 promoter and ORF, we next tested whether the zinc-dependent change in adh1AS transgene levels was dependent upon the expression of the adh1 gene. For these studies, we utilized three different yeast strains: SPCC13B11.02cΔ, nmt1-adh1, and adh1Δ. These strains were used because they express the endogenous adh1 gene at different levels. The SPCC13B11.02cΔ and adh1Δ strains constitutively express or entirely lack the endogenous adh1 gene, respectively. The nmt1-adh1 strain was used because it is a strain in which the endogenous adh1 gene can be expressed at a low basal level following growth in thiamine. For example, when nmt1-adh1 cells are grown in the presence of thiamine, adh1 mRNAs cannot be detected by Northern analysis but can be detected by the more sensitive technique of strand-specific RT-PCR (Figs. 3 and 6A). Fig. 6A shows the relative levels of endogenous adh1 gene expression in each of the strain backgrounds. No adh1 gene expression was detected in adh1Δ cells by strand-specific RT-PCR (data not shown). In addition to using different strain backgrounds to alter the expression level of the endogenous adh1 gene, a new transgene construct (pAS-mTATA) was generated in which the adh1 TATA box was mutated in the full-length pAS(1–3412) transgene. The rationale behind this construct was to generate a transgene construct that expressed only the adh1AS transcript.

FIGURE 6.

Zinc-dependent regulation of the adh1AS transgene requires adh1. A, wild-type, SPCC13B11.02cΔ, nmt1-adh1, and adh1Δ cells were grown in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn). An additional 15 μm thiamine supplement was added to the nmt1-adh1 strain. Total RNA was purified, and strand-specific RT-PCR was used to examine adh1 mRNA levels. The levels of pgk1 transcripts were examined as a loading control following RT-PCR with random hexamers. Values are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of three repeats normalized to the pgk1 control. B, wild-type, adh1Δ, and nmt1-adh1 cells containing Rep3x-pgk1, pAS(1–3412), or pAS-mTATA were grown overnight in EMM. Cells were diluted to A600 = 1.0, and 10-fold serial dilutions were plated onto EMM supplemented with 50 μm thiamine and with (+AA) or without (−AA) 15 μm antimycin A. C, SPCC13B11.02cΔ, nmt1-adh1, and adh1Δ cells that contained the empty vector (vec), pAS(1–3412) (AS), or pAS-mTATA (mTATA) were grown to exponential phase in ZL-EMM (−Zn) or in ZL-EMM supplemented with 200 μm zinc (+Zn) before total RNA was purified for Northern analysis. Blots were probed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

To test whether the adh1 TATA mutation was sufficient to inhibit adh1 gene expression, the pAS(1–3412) and pAS-mTATA transgenes were introduced into adh1Δ cells, and growth was examined on EMM medium. In EMM medium, adh1Δ cells have a slow growth defect (Fig. 6B, vector rows). This slow growth defect was rescued by the introduction of pAS(1–3412), but not by pAS-mTATA. As a second method of examining the effect of the TATA mutation on adh1 levels, the growth of each of the above strains was examined on plates containing antimycin A (Fig. 6B, +AA panels). Because adh1Δ cells rely primarily on respiration for growth, they are unable to grow in the presence of antimycin A, an inhibitor of respiration. Although the full-length antisense transgene (pAS(1–3412)) was able to fully rescue the growth defect of adh1Δ on plates containing antimycin A, pAS-mTATA could only weakly rescue growth. Together, these results suggest that the TATA box mutation significantly reduced adh1 gene expression in the transgene construct. Consistent with our previous results showing that low levels of adh1 gene expression occur in the nmt1-adh1 strain when it is grown in a thiamine-rich medium, the nmt1-adh1 strain was able to grow in medium containing antimycin A in the presence of high thiamine levels (Fig. 6B).

To investigate how adh1 gene expression affected adh1AS transcript levels, Northern analysis was performed using total RNA purified from SPCC13B11.02cΔ, nmt1-adh1, and adh1Δ cells that contained the pAS(1–3412) or pAS-mTATA transgene. In SPCC13B11.02cΔ cells, the pAS-mTATA mutation led to a significant reduction in the zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS transcript levels (Fig. 6C). A similar trend was observed in nmt1-adh1 cells expressing pAS-mTATA. These results are consistent with the zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS transgene levels requiring that adh1 be expressed in cis. Surprisingly, in adh1Δ cells, a different trend was observed. There was no zinc-dependent regulation of the pAS(1–3412) or pAS-mTATA transgene, suggesting that a signal generated at the endogenous locus might be critical to the zinc-dependent regulation or that other factors might be important (see “Discussion”).

DISCUSSION

NATs are generated in the majority of eukaryotic cells, where they can have important regulatory functions. Despite their importance in general gene regulation, very little is known about the mechanisms that control antisense levels. In this study, we have identified a NAT that is generated at the adh1 locus in response to zinc limitation. Increased expression of this antisense transcript leads to reduced levels of the partner adh1 mRNA, indicating that the adh1AS transcript has a regulatory role in controlling adh1 gene expression.

Here, we found that the levels of the adh1AS transcript are regulated according to cellular zinc status. Specifically, we have shown that the adh1AS transcript is transcribed at a higher level in zinc-limited cells relative to zinc-replete cells. We have also shown that adh1AS transcript levels are regulated by a second mechanism that is independent of the adh1AS promoter.

In other organisms, a number of transcription factors have been identified that are able to “sense” and regulate gene expression in response to changes in intracellular zinc levels. For example, in the yeast S. cerevisiae, the zinc-responsive transcriptional activator Zap1 plays a central role in zinc homeostasis by activating the expression of zinc-uptake genes in zinc-limited cells (38, 39). Although there is no Zap1 homolog in fission yeast, our data are consistent with a zinc-responsive factor controlling the expression level of the adh1AS transcript. The identity of this factor will therefore be important to understand the mechanism behind zinc-dependent transcriptional regulation in S. pombe.

Although the transcriptional regulation of the adh1AS transcript is sufficient to explain the zinc-dependent changes in adh1 sense and antisense transcript levels, we have shown that the adh1AS transcript preferentially accumulated in zinc-limited cells when the adh1AS transcript was expressed from the nmt1 promoter (Fig. 3B). A similar result was observed when an adh1AS transgene was expressed from the constitutive pgk1 promoter (Fig. 4B). Together, these results suggest that a second mechanism might contribute to the overall zinc-dependent regulation of adh1 sense and antisense transcript levels. When additional transgene constructs were generated to map the region(s) of the antisense transcript required for this secondary regulation, zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS transcript levels was strongest when adh1 was present in cis. Although the precise regulatory mechanism is unclear, expression of the adh1 gene in cis could potentially alter the expression or processing of the adh1AS transcript in zinc-replete cells. Notably, when the nmt1-adh1AS strain was grown to exponential phase in high zinc, a condition was reached in which no adh1AS and adh1 mRNAs accumulated (Fig. 3B, lane 6). One possible explanation for this result is that, in high zinc, the reduction in adh1AS transcripts is through a mechanism that requires a double-stranded RNA intermediate or the elimination of both sense and antisense transcripts. Although this would seem a wasteful mechanism, in a wild-type cell, the adh1AS transcript is under the transcriptional control of a zinc-regulated promoter. As a consequence, only basal levels of the adh1AS transcript are produced in high zinc, and only small levels of adh1 mRNAs would need to be sacrificed to eliminate adh1AS transcripts.

Although the adh1AS transcript primarily acts in cis to regulate adh1 mRNA levels, it also can act in trans. In trans, the reduction in adh1 mRNAs appears to be independent of zinc and instead correlates with the levels of adh1AS transcripts (Fig. 4). It is also relatively weak because adh1 mRNAs will accumulate despite high levels of the adh1AS transcript being present. The observed regulation in trans might therefore be a result of a general mechanism to eliminate sense/antisense pairs.

An unexpected result was that adh1AS transcripts accumulated under all conditions when the pgk1-driven antisense transgene (pAS(1–3412)) was introduced in adh1Δ cells. One explanation of this result is that a trans-acting signal generated at the endogenous adh1 gene locus is critical for the regulation of the adh1AS transgene. An alternative possibility is that the lack of regulation arose from experimental differences between the strains. One concern with adh1Δ is that even in the presence of the pAS(1–3412) transgene, adh1Δ cells grow slowly in ZL-EMM and must be grown for longer periods to reach zinc limitation.3 When the nmt1-adh1AS strain was grown for longer periods, adh1AS transcripts accumulated in zinc-limited and zinc-replete cells (Fig. 3C). Thus, the regulation of adh1AS transcript levels by zinc might depend on growth phase or be influenced by the time of growth in a given medium. For example, prolonged expression of the adh1AS transcript might inhibit adh1 gene expression, preventing zinc-dependent regulation of adh1AS transcript levels. Future studies are needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

If the adh1AS transcript is typically transcribed in a zinc-limited cell, why would cells require a mechanism to eliminate adh1AS transcripts in high zinc? Such a mechanism might be advantageous to yeast during transitions from a zinc-limiting to a zinc-rich environment. For example, the rapid removal of adh1AS transcripts upon zinc exposure would allow the rapid reestablishment of adh1 gene expression. A different possibility is that the adh1AS transcript has another unknown function, and this secondary mechanism exists to ensure that basal levels of adh1AS transcripts do not accumulate in zinc-replete cells. Finally, bidirectional transcription is critical to establish and maintain RNAi-mediated gene silencing in S. pombe. Because, adh1 is the major alcohol dehydrogenase gene in S. pombe, the rapid elimination of basal adh1AS transcripts generated under zinc-replete conditions could be a mechanism to ensure that an RNAi response is not initiated at this locus when zinc is in excess. Consistent with this idea, very low levels of adh1 siRNAs have been detected in S. pombe (40). However, adh1AS transgene levels are regulated by zinc in strains that lack genes required for RNAi (data not shown).

Antisense transcripts are generated at a large number of gene loci. Antisense transcripts can arise from transcriptional read-through, bidirectional transcriptional initiation from a single promoter, transcription from nucleosome-free regions in the 3′-untranslated region, or increased or decreased transcription from an antisense promoter region (13, 41, 42). Here, we have shown that the regulation of antisense levels can be far more complex, with multiple mechanisms acting together to control the levels of transcripts within sense/antisense pairs. In a wide variety of species, antisense transcripts are commonly generated in response to different stress or environmental conditions (7, 8, 43, 44). Aberrant expression of antisense transcripts or altered ratios of sense to antisense transcripts are also frequently observed in a wide range of human cancers and complex diseases (10, 45–48). Because the precise levels of antisense transcripts can significantly impact gene expression, further studies of how antisense transcript levels are regulated by changes in the environment are likely to provide important insight into the mechanisms behind altered gene expression and disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Andrew Patrick, Spencer Rupard, and Dr. Kurt Runge for helping with strain generation and Drs. Jian-Qiu Wu and Danesh Moazed for kindly providing the yeast strains and plasmids that were used in this study. We thank Drs. R. Michael Townsend, Anita Hopper, and James Hopper and members of the Bird laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM056285 (to Dave Eide) and seed grant money from National Institutes of Health/NCI Leukemia Spore Grant CA140158. This work was also supported by a graduate student fellowship from the Center for RNA Biology at The Ohio State University (to K. M. E.) and National Science Foundation Biological Sciences REU Grant DBI 0750631 (to C. A.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2.

Array data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under GEO accession number GSE39701.

K. M. Ehrensberger and A. J. Bird, unpublished data.

- NAT

- natural antisense transcript

- ZL-EMM

- zinc-limiting Edinburgh minimal medium.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hahn S., Young E. T. (2011) Transcriptional regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: transcription factor regulation and function, mechanisms of initiation, and roles of activators and coactivators. Genetics 189, 705–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehrensberger K. M., Bird A. J. (2011) Hammering out details: regulating metal levels in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Günther V., Lindert U., Schaffner W. (2012) The taste of heavy metals: gene regulation by MTF-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1416–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U., Galy B., Camaschella C. (2010) Two to tango: regulation of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142, 24–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Puig S., Askeland E., Thiele D. J. (2005) Coordinated remodeling of cellular metabolism during iron deficiency through targeted mRNA degradation. Cell 120, 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsui A., Ishida J., Morosawa T., Mochizuki Y., Kaminuma E., Endo T. A., Okamoto M., Nambara E., Nakajima M., Kawashima M., Satou M., Kim J. M., Kobayashi N., Toyoda T., Shinozaki K., Seki M. (2008) Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis under drought, cold, high-salinity and ABA treatment conditions using a tiling array. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 1135–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ni T., Tu K., Wang Z., Song S., Wu H., Xie B., Scott K. C., Grewal S. I., Gao Y., Zhu J. (2010) The prevalence and regulation of antisense transcripts in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS ONE 5, e15271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yassour M., Pfiffner J., Levin J. Z., Adiconis X., Gnirke A., Nusbaum C., Thompson D. A., Friedman N., Regev A. (2010) Strand-specific RNA sequencing reveals extensive regulated long antisense transcripts that are conserved across yeast species. Genome Biol. 11, R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Faghihi M. A., Kocerha J., Modarresi F., Engström P. G., Chalk A. M., Brothers S. P., Koesema E., St. Laurent G., 3rd, Wahlestedt C. (2010) RNAi screen indicates widespread biological function for human natural antisense transcripts. PLoS ONE 5, e13177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faghihi M. A., Modarresi F., Khalil A. M., Wood D. E., Sahagan B. G., Morgan T. E., Finch C. E., St. Laurent G., 3rd, Kenny P. J., Wahlestedt C. (2008) Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of β-secretase. Nat. Med. 14, 723–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houseley J., Rubbi L., Grunstein M., Tollervey D., Vogelauer M. (2008) A ncRNA modulates histone modification and mRNA induction in the yeast GAL gene cluster. Mol. Cell 32, 685–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camblong J., Beyrouthy N., Guffanti E., Schlaepfer G., Steinmetz L. M., Stutz F. (2009) Trans-acting antisense RNAs mediate transcriptional gene cosuppression in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 23, 1534–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hongay C. F., Grisafi P. L., Galitski T., Fink G. R. (2006) Antisense transcription controls cell fate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 127, 735–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Werner A., Swan D. (2010) What are natural antisense transcripts good for? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1144–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J. T., Zhang Y., Kong L., Liu Q. R., Wei L. (2008) Trans-natural antisense transcripts including noncoding RNAs in 10 species: implications for expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 4833–4844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Faghihi M. A., Wahlestedt C. (2009) Regulatory roles of natural antisense transcripts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 637–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prescott E. M., Proudfoot N. J. (2002) Transcriptional collision between convergent genes in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8796–8801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beltran M., Puig I., Peña C., García J. M., Alvarez A. B., Peña R., Bonilla F., de Herreros A. G. (2008) A natural antisense transcript regulates Zeb2/Sip1 gene expression during Snail1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genes Dev. 22, 756–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters N. T., Rohrbach J. A., Zalewski B. A., Byrkett C. M., Vaughn J. C. (2003) RNA editing and regulation of Drosophila 4f-rnp expression by sas-10 antisense readthrough mRNA transcripts. RNA 9, 698–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moazed D. (2009) Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature 457, 413–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carthew R. W., Sontheimer E. J. (2009) Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bähler J., Wu J. Q., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A., 3rd, Steever A. B., Wach A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Myers A. M., Tzagoloff A., Kinney D. M., Lusty C. J. (1986) Yeast shuttle and integrative vectors with multiple cloning sites suitable for construction of lacZ fusions. Gene 45, 299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keeney J. B., Boeke J. D. (1994) Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 136, 849–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Forsburg S. L. (1993) Comparison of Schizosaccharomyces pombe expression systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2955–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao H., Eide D. J. (1997) Zap1p, a metalloregulatory protein involved in zinc-responsive transcriptional regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5044–5052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dutrow N., Nix D. A., Holt D., Milash B., Dalley B., Westbroek E., Parnell T. J., Cairns B. R. (2008) Dynamic transcriptome of Schizosaccharomyces pombe shown by RNA-DNA hybrid mapping. Nat. Genet. 40, 977–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peter M., Gartner A., Horecka J., Ammerer G., Herskowitz I. (1993) FAR1 links the signal transduction pathway to the cell cycle machinery in yeast. Cell 73, 747–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roberts D. N., Stewart A. J., Huff J. T., Cairns B. R. (2003) The RNA polymerase III transcriptome revealed by genome-wide localization and activity-occupancy relationships. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14695–14700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guarente L. (1983) Yeast promoters and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 101, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Auld D. S., Bergman T. (2008) Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families: the role of zinc for alcohol dehydrogenase structure and function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3961–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Smidt O., du Preez J. C., Albertyn J. (2008) The alcohol dehydrogenases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a comprehensive review. FEMS Yeast Res. 8, 967–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dainty S. J., Kennedy C. A., Watt S., Bähler J., Whitehall S. K. (2008) Response of Schizosaccharomyces pombe to zinc deficiency. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 454–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Komarnitsky P., Cho E. J., Buratowski S. (2000) Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 14, 2452–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maundrell K. (1990) nmt1 of fission yeast. A highly transcribed gene completely repressed by thiamine. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10857–10864 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Camblong J., Iglesias N., Fickentscher C., Dieppois G., Stutz F. (2007) Antisense RNA stabilization induces transcriptional gene silencing via histone deacetylation in S. cerevisiae. Cell 131, 706–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iida T., Nakayama J., Moazed D. (2008) siRNA-mediated heterochromatin establishment requires HP1 and is associated with antisense transcription. Mol. Cell 31, 178–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu C. Y., Bird A. J., Chung L. M., Newton M. A., Winge D. R., Eide D. J. (2008) Differential control of Zap1-regulated genes in response to zinc deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 9, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eide D. J. (2009) Homeostatic and adaptive responses to zinc deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18565–18569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bühler M., Spies N., Bartel D. P., Moazed D. (2008) TRAMP-mediated RNA surveillance prevents spurious entry of RNAs into the Schizosaccharomyces pombe siRNA pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1015–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neil H., Malabat C., d'Aubenton-Carafa Y., Xu Z., Steinmetz L. M., Jacquier A. (2009) Widespread bidirectional promoters are the major source of cryptic transcripts in yeast. Nature 457, 1038–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu Z., Wei W., Gagneur J., Perocchi F., Clauder-Münster S., Camblong J., Guffanti E., Stutz F., Huber W., Steinmetz L. M. (2009) Bidirectional promoters generate pervasive transcription in yeast. Nature 457, 1033–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang X., Xia J., Lii Y. E., Barrera-Figueroa B. E., Zhou X., Gao S., Lu L., Niu D., Chen Z., Leung C., Wong T., Zhang H., Guo J., Li Y., Liu R., Liang W., Zhu J. K., Zhang W., Jin H. (2012) Genome-wide analysis of plant nat-siRNAs reveals insights into their distribution, biogenesis and function. Genome Biol. 13, R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu Z., Wei W., Gagneur J., Clauder-Münster S., Smolik M., Huber W., Steinmetz L. M. (2011) Antisense expression increases gene expression variability and locus interdependency. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yu W., Gius D., Onyango P., Muldoon-Jacobs K., Karp J., Feinberg A. P., Cui H. (2008) Epigenetic silencing of tumour suppressor gene p15 by its antisense RNA. Nature 451, 202–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maruyama R., Shipitsin M., Choudhury S., Wu Z., Protopopov A., Yao J., Lo P. K., Bessarabova M., Ishkin A., Nikolsky Y., Liu X. S., Sukumar S., Polyak K. (2012) Altered antisense-to-sense transcript ratios in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2820–2824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Taft R. J., Pang K. C., Mercer T. R., Dinger M., Mattick J. S. (2010) Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. J. Pathol. 220, 126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tufarelli C., Stanley J. A., Garrick D., Sharpe J. A., Ayyub H., Wood W. G., Higgs D. R. (2003) Transcription of antisense RNA leading to gene silencing and methylation as a novel cause of human genetic disease. Nat. Genet. 34, 157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.