In the absence of elongation factor EF-G, ribosomes undergo spontaneous, thermally driven fluctuation between the pre-translocation (classical) and intermediate (hybrid) states of translocation. These fluctuations do not result in productive mRNA translocation. Extending previous findings that the antibiotic sparsomycin induces translocation, the authors identify additional peptidyl transferase inhibitors that trigger mRNA translocation. They find that antibiotics that bind the peptidyl transferase A site induce mRNA translocation, whereas those that do not occupy the A site fail to induce translocation. The results support the idea that the ribosome is a Brownian ratchet machine, whose intrinsic dynamics can be rectified into unidirectional translocation by ligand binding.

Keywords: antibiotics, Brownian ratchet mechanism, mRNA translocation, ribosome

Abstract

In the absence of elongation factor EF-G, ribosomes undergo spontaneous, thermally driven fluctuation between the pre-translocation (classical) and intermediate (hybrid) states of translocation. These fluctuations do not result in productive mRNA translocation. Extending previous findings that the antibiotic sparsomycin induces translocation, we identify additional peptidyl transferase inhibitors that trigger productive mRNA translocation. We find that antibiotics that bind the peptidyl transferase A site induce mRNA translocation, whereas those that do not occupy the A site fail to induce translocation. Using single-molecule FRET, we show that translocation-inducing antibiotics do not accelerate intersubunit rotation, but act solely by converting the intrinsic, thermally driven dynamics of the ribosome into translocation. Our results support the idea that the ribosome is a Brownian ratchet machine, whose intrinsic dynamics can be rectified into unidirectional translocation by ligand binding.

INTRODUCTION

During protein synthesis, mRNA and tRNAs are moved through the ribosome by the dynamic process of translocation. Sequential movement of tRNAs from the A (aminoacyl) site to the P (peptidyl) site to the E (exit) site is coupled to movement of their associated codons in the mRNA (Spirin 2004). Translocation is catalyzed by a universally conserved elongation factor (EF-G in prokaryotes and EF-2 in eukaryotes) (Spirin 2004).

Ribosomal translocation takes place in two steps, in which the acceptor ends of the tRNAs first move relative to the large ribosomal subunit (50S in bacteria), from the classical A/A and P/P states into hybrid A/P and P/E states, followed by the movement of their anticodon ends on the small ribosomal subunit (30S), coupled with mRNA movement, into the post-translocational P/P and E/E states (Fig. 1A; Moazed and Noller 1989). While hybrid state formation can occur spontaneously, translocation on the small subunit requires EF-G and GTP (Moazed and Noller 1989). Formation of the hybrid state intermediate is accompanied by a counterclockwise rotation of the small ribosomal subunit (Valle et al. 2003; Ermolenko et al. 2007a; Agirrezabala et al. 2008; Julian et al. 2008; Dunkle et al. 2011). Blocking intersubunit rotation by formation of a disulfide cross-link abolishes translocation (Horan and Noller 2007). Single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) studies demonstrate that pre-translocation ribosomes undergo spontaneous intersubunit rotational movement in the absence of ribosomal factors and GTP (Cornish et al. 2008), fluctuating between two conformations corresponding to the classical and hybrid states of the tRNA translocational cycle (Fig. 1A; Blanchard et al. 2004; Ermolenko et al. 2007b; Munro et al. 2007; Fei et al. 2008). However, under most experimental conditions, in the absence of EF-G, these fluctuations do not result in productive translocation of mRNA and tRNAs on the small ribosomal subunit. EF-G transiently stabilizes the hybrid state conformation (Pan et al. 2007; Spiegel et al. 2007; Ermolenko and Noller 2011) and catalyzes mRNA translocation during the reverse (clockwise) rotation of the small subunit (Ermolenko and Noller 2011). mRNA translocation is likely accompanied by additional conformational changes within the small ribosomal subunit, i.e., “swiveling” motion of the “head” relative to the “body” and the “platform” of the 30S, which is orthogonal to the intersubunit rotation (Schuwirth et al. 2005; Ratje et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2012). Despite recent progress in studies of the translocation mechanism, the question remains: How does EF-G convert unproductive spontaneous fluctuations of the ribosome and tRNAs into efficient translocation of tRNA and mRNA?

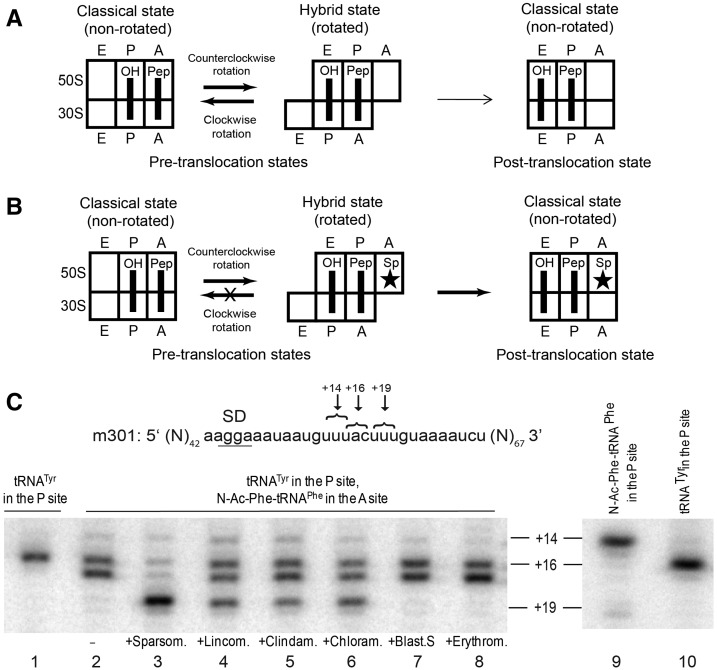

FIGURE 1.

Antibiotic-induced translocation of mRNA. (A) Schematic depiction of intersubunit rotation and tRNA movement in pre-translocation ribosomes. (Movement of mRNA is not shown.) Under most experimental conditions, spontaneous, nonproductive forward and reverse intersubunit rotation, coupled to fluctuations between the classical and hybrid states of tRNA binding, does not result in mRNA translocation in the absence of EF-G. (B) Schematic illustration of hypothesized mechanism of sparsomycin-induced translocation (see details in the text). Binding of sparsomycin to the 50S A site is indicated by a star. (C) Toeprinting assay of antibiotic-induced mRNA translocation. A pre-translocation complex was made by binding deacylated tRNATyr to the P site (lanes 1 and 10) and the peptidyl-tRNA analog N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe to the A site (lane 2) in the presence of mRNA 301. Pre-translocation ribosomes were incubated with sparsomycin (lane 3), lincomycin (lane 4), clindamycin (lane 5), chloramphenicol (lane 6), blasticidin S (lane 7), and erythromycin (lane 8). A toeprint band at +16 corresponds to the pre-translocation complex, a band at +19 is the product of translocation, and a band at +14 is the product of direct binding of N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe to the upstream Phe codon (lane 9).

The spontaneity of intersubunit rotational movement prompted several groups to apply the theoretical framework of the Brownian ratchet mechanism to the analysis of ribosomal translocation (Frank and Gonzalez 2010; Ratje et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2011). In Brownian ratchet models, unidirectional movement of macromolecules is enabled by ligand binding and chemical reactions that rectify spontaneous thermal fluctuations of macromolecules by preferentially locking in a preferred state (Howard 2006). (By “rectify,” we mean conversion of movement, which periodically reverses direction, to unidirectional motion.) Thus, ligand binding is analogous to the pawl of a mechanical ratchet. However, the hypothesis that the ribosome is a Brownian ratchet machine whose spontaneous dynamics can be converted into translation (Spirin 2004; Frank and Gonzalez 2010; Ratje et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2011) has not been rigorously tested. Moreover, the exact nature of the pawl of the translocation ratchet and its mechanics is unknown.

Here, we exploit the use of antibiotics as an example of rectification of ribosomal dynamics via ligand binding. Previously, an intriguing translocation phenomenon was discovered: The antibiotic sparsomycin, a peptidyl transferase inhibitor that binds to the large ribosomal subunit, was found to induce efficient translocation of tRNA and mRNA on the small subunit (Fredrick and Noller 2003). Early studies on the inhibitory action of sparsomycin showed that it increases the affinity of tRNA for the P site while interfering with binding to the A site (Monro et al. 1969; Pestka 1969; Lazaro et al. 1991). Consistent with these findings, crystallographic studies of sparsomycin bound to the large ribosomal subunit showed that its uracil moiety interacts with the 3′-terminal cytosine and adenine of the P-site tRNA, while its sulfur-rich tail overlaps with the binding position of the aminoacyl moiety and terminal adenine of the A-site tRNA (Hansen et al. 2003). It was originally hypothesized that sparsomycin induces translation by stabilization of the post-translocation state of the ribosome via interaction with peptidyl-tRNA in the 50S P site (Fredrick and Noller 2003). However, the observation that spontaneous movement of the acceptor ends of tRNAs on the large subunit does not result in efficient translocation on the small subunit (Fig. 1A; Moazed and Noller 1989; Blanchard et al. 2004; Fei et al. 2008) suggests that this explanation may be insufficient. An alternative possibility is that sparsomycin induces ribosomal translocation by sterically blocking the reverse movement of peptidyl-tRNA from the hybrid A/P to the classical A/A state as the ribosome spontaneously fluctuates between the rotated and nonrotated conformations (Fig. 1B). In this model, sparsomycin plays the role of a pawl in a Brownian ratchet. To test this possibility, we examined the ability of other antibiotics that bind to the 50S A site but are chemically different from sparsomycin, to induce mRNA translocation.

RESULTS

Antibiotics that bind to the 50S A site induce mRNA translocation

Biochemical and crystallographic studies have identified several peptidyl transferase inhibitors that bind to the A site of the large subunit, including chloramphenicol, puromycin, and the lincosamides lincomycin and clindamycin (Schlunzen et al. 2001; Hansen et al. 2003; Wilson 2009; Bulkley et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2010). These antibiotics compete for 50S A-site binding with each other as well as with aminoacylated oligonucleotide fragments corresponding to the 3′ terminus of aminoacyl-tRNA (Celma et al. 1971; Fernandez-Munoz et al. 1971; Contreras and Vazquez 1977; Wilson 2009). We tested the ability of chloramphenicol, lincomycin, clindamycin, and puromycin to induce translocation using a toeprinting assay, which uses primer extension to monitor mRNA movement on the ribosome (Fig. 1C; Joseph and Noller 1998). Binding of the defined m301 mRNA (Fredrick and Noller 2003) and deacylated tRNATyr produced a toeprint band corresponding to position +16, indicating the positioning of the Tyr codon UAC in the ribosomal P site by tRNATyr (Fig. 1C, lane 1) (+16 corresponds to the position on the mRNA relative to the first nucleotide of the P-site codon where reverse transcriptase stops upon encountering the ribosome). Addition of the peptidyl-tRNA analog N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe resulted in formation of a pre-translocation complex, as evidenced by the appearance of a doublet band indicative of peptidyl-tRNA binding to the A site (Fig. 1C, lane 2; Joseph and Noller 1998). Incubation of the pre-translocation complex with sparsomycin shifted the toeprint stop to position +19, indicating translocation of mRNA by one codon, in agreement with previous observations (Fig. 1C, lane 3; Fredrick and Noller 2003). Incubation of pre-translocation ribosomes with lincomycin, clindamycin, or chloramphenicol also resulted in appearance of a stop at position +19 (Fig. 1C, lanes 4–6; Fig. 2). The m301 sequence contains an upstream UUU codon overlapping with the tyrosine codon UAC (Fig. 1C). Since this UUU codon is positioned more optimally with respect to the Shine–Dalgarno sequence, it is preferentially used over the downstream UUU codon when N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe is bound directly to the P site (Fredrick and Noller 2003), evidenced by appearance of a +14 toeprint stop (Fig. 1C, lane 9). Thus, the appearance of the +19 toeprint induced by the 50S A-site antibiotics corresponds to authentic mRNA translocation and cannot be explained by the possibility of dissociation and reassociation of ribosomal complexes.

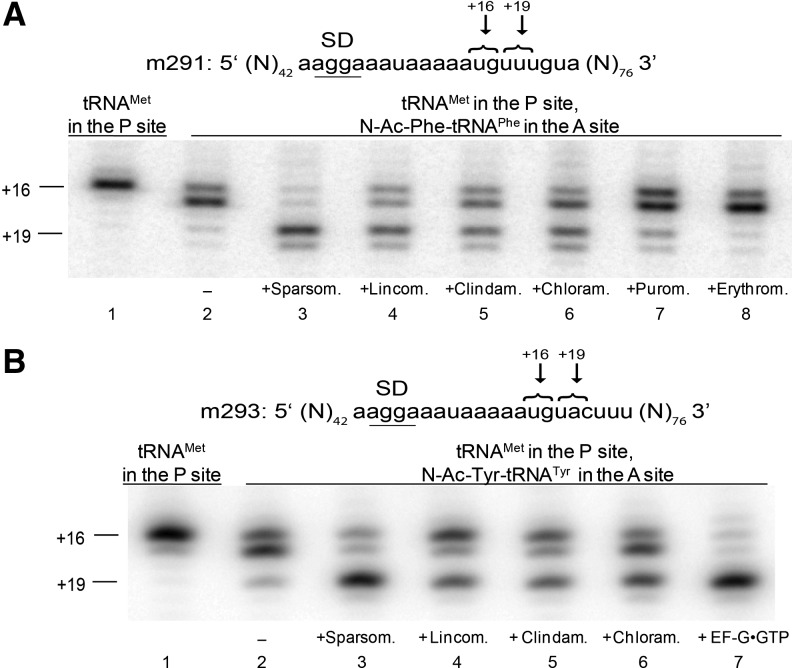

FIGURE 2.

Antibiotic-induced translocation of different mRNA and tRNA species. (A) A pre-translocation complex made by binding deacylated tRNAMet to the P site (lane 1) and the peptidyl-tRNA analog N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe to the A site (lane 2) in the presence of mRNA 291 was incubated with sparsomycin (lane 3), lincomycin (lane 4), clindamycin (lane 5), chloramphenicol (lane 6), puromycin (lane 7), or erythromycin (lane 8). (B) A pre-translocation complex made by binding deacylated tRNAMet to the P site (lane 1) and peptidyl-tRNA analog N-Ac-Tyr-tRNATyr to the A site (lane 2) in the presence of mRNA 293 was incubated with sparsomycin (lane 3), lincomycin (lane 4), clindamycin (lane 5), chloramphenicol (lane 6), or EF-G and GTP (lane 7).

The extent of mRNA translocation in the presence of lincomycin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol varied from 40% for clindamycin to 60% for lincomycin, less efficient than sparsomycin-induced translocation (near 90% complete), but dramatically enhanced relative to spontaneous translocation, which was virtually undetectable. The 50S A-site binding antibiotic puromycin also reproducibly stimulated translocation in 15%–20% of ribosomes (Fig. 2A, lane 7). However, we excluded puromycin from further analysis because of its significantly lower translocation efficiency, relative to other A-site antibiotics. The antibiotics blasticidin S and erythromycin, which bind to the P site in the peptidyl transferase cavity (Hansen et al. 2003) and in the peptide exit tunnel (Schlunzen et al. 2001), respectively, but do not occupy the A site fail to induce mRNA translocation (Fig. 1C, lanes 7,8; Fig. 2A, lane 8). Therefore, only those peptidyl-transferase inhibitors that bind to the 50S A site were found to induce mRNA translocation.

Properties of antibiotic-induced translocation

Lincomycin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol promoted translocation of a variety of different mRNA and tRNA combinations: mRNA m301 with tRNATyr and N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe (Fig. 1C); m291 (Fredrick and Noller 2002) with tRNAMet and N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe (Fig. 2A); and m293 (Fredrick and Noller 2002) with tRNAMet and N-Ac-Tyr-tRNATyr (Fig. 2B). Thus, A-site binding antibiotics induce translocation regardless of the identity of A- and P-site tRNA species.

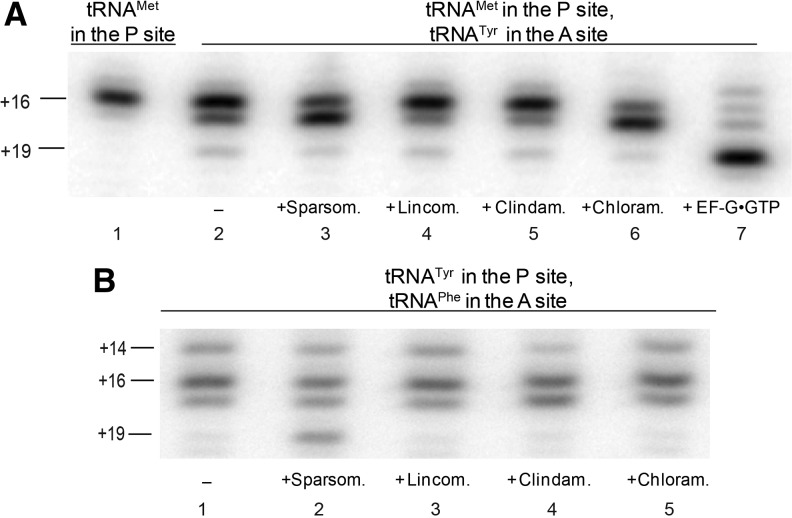

Crystallographic studies showed that the sulfur-rich tail moiety of sparsomycin, the prolyl moiety of clindamycin, and the nitrobenzene moiety of chloramphenicol clash with the aminoacyl moiety of A-site tRNA (Hansen et al. 2003; Bulkley et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2010). Accordingly, we next tested whether the A-site antibiotics can induce translocation in pre-translocation ribosomes containing deacylated tRNA in the A site. When A-site peptidyl-tRNA was replaced with deacylated tRNA, the ability of lincomycin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol to induce translocation was completely abolished (Fig. 3). The efficiency of sparsomycin-induced translocation also dramatically decreased (Fig. 3). In contrast, EF-G-catalyzed translocation remained complete (Fig. 3A, lane 7). Therefore, antibiotic-induced translocation requires the presence of an aminoacyl moiety at the A-site tRNA.

FIGURE 3.

Translocation of complexes containing deacylated A-site tRNA. (A) A pre-translocation complex made by binding deacylated tRNAMet to the P site (lane 1) and deacylated tRNATyr to the A site (lane 2) in the presence of mRNA 293 was incubated with sparsomycin (lane 3), lincomycin (lane 4), clindamycin (lane 5), chloramphenicol (lane 6), or EF-G and GTP (lane 7). (B) A pre-translocation complex made by binding deacylated tRNATyr to the P site and deacylated tRNAPhe to the A site in the presence of mRNA 301 (lane 1) was incubated with sparsomycin (lane 2), lincomycin (lane 3), clindamycin (lane 4), and chloramphenicol (lane 5).

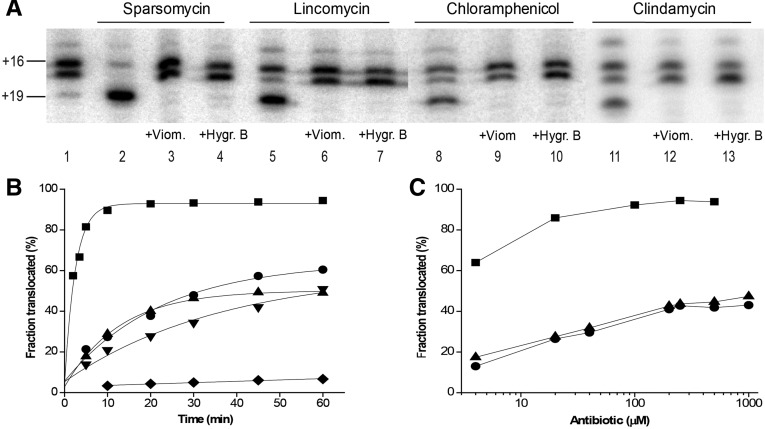

Sparsomycin-, chloramphenicol-, lincomycin-, and clindamycin-induced translocation was completely eliminated in the presence of antibiotics viomycin and hygromycin B, which are known to inhibit EF-G-catalyzed translocation without hindering EF-G binding or GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 4A; Peske et al. 2004). Viomycin and hygromycin B bind >50 Å away from the peptidyl-transferase cavity at the intersubunit interface and decoding site of the small subunit, respectively, and therefore cannot directly compete with peptidyl-transferase inhibitors for binding (Borovinskaya et al. 2008; Stanley et al. 2010). The inhibition of antibiotic-induced translocation by viomycin and hygromycin B provides evidence for underlying similarities between the mechanisms of antibiotic- and EF-G-dependent translocation.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of antibiotic-induced mRNA translocation. (A) Inhibition of antibiotic-induced translocation by viomycin and hygromycin B. Pre-translocation ribosomes containing deacylated tRNATyr in the P site and N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe in the A site (lane 1) were first pre-incubated with the translocation inhibitors viomycin (lanes 3,6,9,12) or hygromycin B (lanes 4,7,10,13) and then incubated with sparsomycin (lanes 2–4), lincomycin (lanes 5–7), chloramphenicol (lanes 8–10), or clindamycin (lanes 11–13) for 30 min at 37°C. In control experiments (lanes 2,5,8,11), no translocation inhibitor was added. (B) Kinetics of mRNA translocation in the presence of sparsomycin (▪), lincomycin (•), chloramphenicol (▴), or clindamycin (▾). (♦) Spontaneous translocation in the absence of antibiotics. (Black lines) Single exponential fits. (C) Dependence of mRNA translocation (30 min at 37°C) on concentration of sparsomycin (▪), lincomycin (•), or chloramphenicol (▴).

Using the toeprinting assay, we measured the kinetics of antibiotic-induced translocation, facilitated by terminating the translocation reaction at various time points with viomycin (Fig. 4B; Fredrick and Noller 2003). Fitting of the kinetic data to single exponentials gave apparent first-order rate constants of 0.04 min−1, 0.03 min−1, and 0.08 min−1 for lincomycin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol, respectively. Although these rates are about fivefold to 10-fold slower than that of sparsomycin-induced translocation (0.4 min−1) (Fig. 4B; Fredrick and Noller 2003), they are about two orders of magnitude faster than the estimated rate of 0.8 × 10−3 min−1 for spontaneous translocation (Fig. 4B; Fredrick and Noller 2003). The extent of translocation also depended on antibiotic concentration (Fig. 4C). Maximum translocation efficiency was achieved at ∼200 µM chloramphenicol or lincomycin. Further increases in antibiotic concentration did not lead to an increase in the fraction of translocated mRNA (Fig. 4C). It is not immediately clear why translocation in the presence of chloramphenicol and lincomycin does not reach completion. Possible explanations are considered in the Discussion below. Nevertheless, our results unambiguously demonstrate the ability of A-site binding antibiotics to significantly stimulate mRNA translocation.

Effect of peptidyl-transferase inhibitors on intersubunit movement

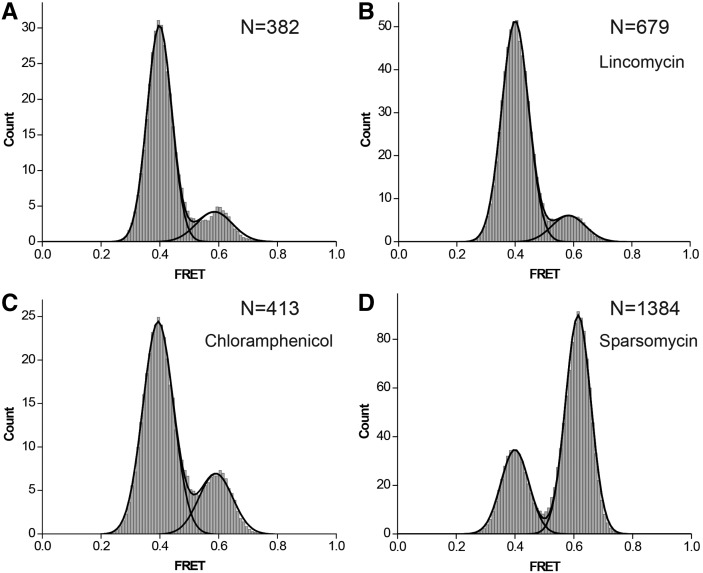

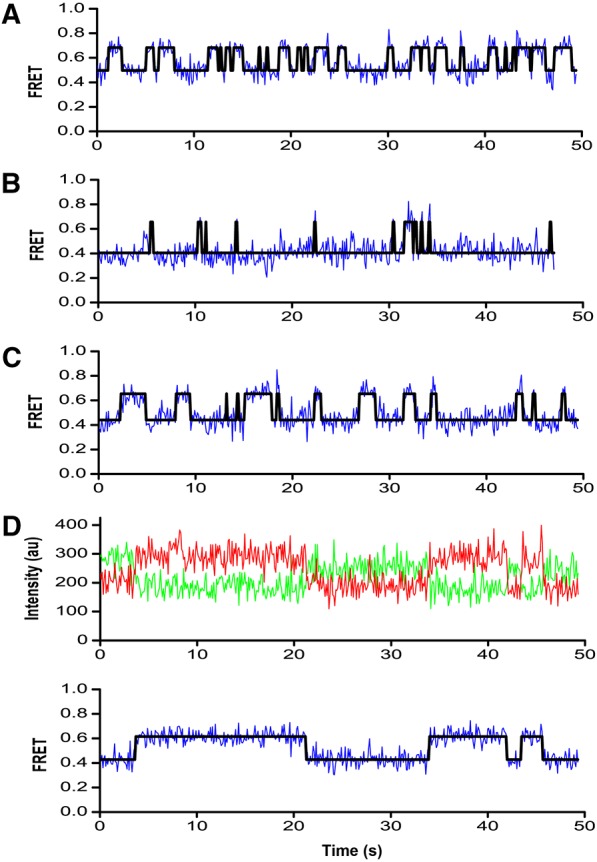

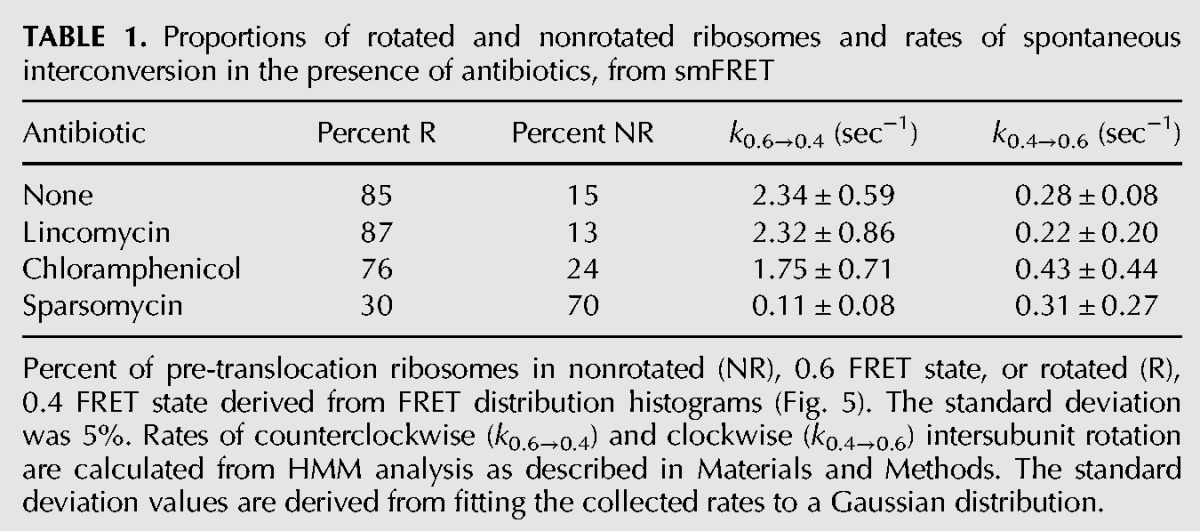

We next tested whether sparsomycin, lincomycin, and chloramphenicol affected the equilibrium between the rotated and nonrotated conformations of the ribosome and accelerated the rates of intersubunit rotation, which underlie ribosomal translocation. We previously developed a method to follow intersubunit movement of the ribosome by measuring smFRET between fluorophores attached to protein S6 on the platform of the small subunit and protein L9 on the large subunit, which is juxtaposed with S6 across the subunit interface. Using this assay in combination with total internal reflection microscopy, we previously demonstrated spontaneous fluctuation of single pre-translocation ribosomes between FRET values of 0.6 and 0.4 that correspond to the nonrotated (classical) and rotated (hybrid) states, respectively (Fig. 1A). Measurement of the effects of antibiotics on the structural dynamics of pre-translocation ribosomes is complicated by the translocation induced by binding of the antibiotic. To overcome this problem, we used fluorescently labeled complexes containing a single deacylated tRNA bound to the P site, since translocation requires the presence of tRNAs in both the A and P sites (Joseph and Noller 1998). Our previous smFRET experiments demonstrated that the intersubunit dynamics of ribosomes containing a single deacylated tRNA in the P site and authentic pre-translocation complexes are very similar (Cornish et al. 2008). Consistent with our previous results, a majority (85% ± 5%) of ribosomes containing tRNATyr in the P site were in the rotated (0.4 FRET) state (Fig. 5A), frequently transitioning into the nonrotated (0.6 FRET) conformation and back, at a rate of 0.3 sec−1 (Fig. 6; Table 1). Neither chloramphenicol nor lincomycin significantly affected these intersubunit dynamics (Fig. 5B,C; Table 1). In contrast, in the presence of sparsomycin, only 30% of the ribosomes were observed in the rotated conformation (Fig. 5D). Sparsomycin binding caused a 20-fold decrease in the rate of counterclockwise rotation without affecting the rate of clockwise rotation (Table 1). Sparsomycin was shown to enhance binding of tRNA to the 50S P site via interaction with the two 3′-terminal nucleotides of tRNA (Hansen et al. 2003; Wilson 2009). Thus, sparsomycin appears to favor binding of the deacylated tRNA in the classical P/P state in the nonrotated conformation of the ribosome. Nevertheless, sparsomycin-bound ribosomes remain highly dynamic, fluctuating between the nonrotated (classical) and rotated (hybrid) states at a rate of 0.1–0.3 sec−1 (Fig. 6; Table 1) that is at least 10-fold faster than the rate of intersubunit rotation in post-translocation ribosomes, which are predominantly fixed in the nonrotated conformation (Cornish et al. 2008). Taken together, our smFRET data suggest that translocation-inducing antibiotics do not accelerate intersubunit rotation, but act solely by converting the intrinsic, thermally driven dynamics of the ribosome into translocation.

FIGURE 5.

Histograms showing distribution of FRET values in different ribosomal complexes. S6-Cy5/L9-Cy3 ribosomes were assembled with mRNA (m301) and deacylated tRNATyr in the P site (A) and incubated with lincomycin (B), chloramphenicol (C), or sparsomycin (D). N is the number of single-molecule traces compiled.

FIGURE 6.

Representative FRET time trajectories of intersubunit movement. Traces show fluorescence intensities observed for Cy3 (green) on ribosomal protein L9 and Cy5 (red) on ribosomal protein S6 and the calculated FRET traces (blue). The fitted curves obtained by Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM) analysis (black) are superimposed on the FRET trajectories. Fluorescence intensities are only shown for the complex in panel D. 70S ribosomes containing tRNATyr in the P site (A) were incubated with lincomycin (B), chloramphenicol (C), or sparsomycin (D).

TABLE 1.

Proportions of rotated and nonrotated ribosomes and rates of spontaneous interconversion in the presence of antibiotics, from smFRET

DISCUSSION

The results of our toeprinting and smFRET experiments show that spontaneous intersubunit rotation of the ribosome can be rectified into unidirectional translocation by binding of antibiotics to the A site. We observe that the ability to induce translocation is not unique to sparsomycin; other chemically distinct peptidyl-transferase inhibitors, which bind to the 50S A site, such as chloramphenicol, and the lincosamides lincomycin and clindamycin, can induce translocation.

The translocation potency of the A-site antibiotics varies dramatically. While sparsomycin induces translocation in >90% of ribosomes, translocation in the presence of lincosamides and chloramphenicol remains incomplete, even at saturating concentrations of these antibiotics (Fig. 4C) and prolonged incubation times, where the kinetics of translocation reach a plateau (Fig. 4B). Translocation in the presence of puromycin is even less efficient (Fig. 2). No translocation was observed in the presence of linezolid, another A-site-binding antibiotic (Li et al. 2011). There may be several factors that contribute to the decreased translocation potency of other A-site antibiotics in comparison to sparsomycin. Stabilization of peptidyl-tRNA binding to the 50S P site through interaction with the uracil moiety of sparsomycin (Figs. 5, 6; Hansen et al. 2003; Wilson 2009) may increase the efficiency of sparsomycin-induced translocation in comparison to other translocation-inducing antibiotics that interact with the 50S A site only. Moreover, the overlap of the sulfur-rich tail of sparsomycin with the 50S A site is more extensive than the structural overlap observed for the other antibiotics. Sparsomycin clashes with both the aminoacyl moiety and the 3′ adenine of the A-site tRNA, while all the other A-site antibiotics overlap only with the aminoacyl moiety (Hansen et al. 2003; Bulkley et al. 2010; Dunkle et al. 2010). Consistent with this observation, sparsomycin is the only antibiotic that induced a detectable level of translocation of deacylated A-site tRNA (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Furthermore, the translocation efficiency of A-site antibiotics appears to correlate loosely with their affinity for the ribosome, decreasing from sparsomycin (Kd < 1 µM) (Lazaro et al. 1987) to chloramphenicol (Kd ∼ 2–6 µM) (Contreras and Vazquez 1977) and the lincosamides (Kd ∼ 4–6 µM) (Contreras and Vazquez 1977; Douthwaite 1992) to linezolid (Kd ∼ 20 µM) (Lin et al. 1997) and puromycin (Kd ∼ 3–4 mM) (Wohlgemuth et al. 2006). Recently, it has been demonstrated that while neither linezolid nor the pseudouridine moiety of sparsomycin, which binds to the A and P sites of large subunit, respectively, can stimulate mRNA translocation by themselves, a linezolid–pseudouridine conjugate can induce translocation in a fraction of ribosomes (Li et al. 2011). Conjugation of linezolid with the pseudouridine moiety of sparsomycin likely enhances the translocation potency of linezolid by increasing its binding affinity for the ribosome.

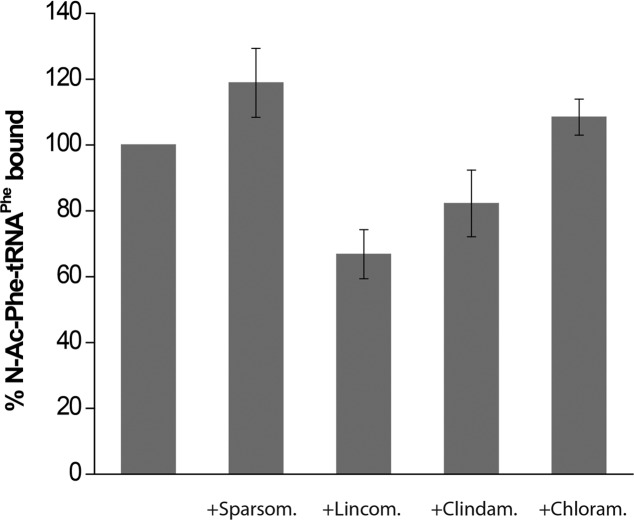

In addition to binding affinity, other factors may affect the translocation efficiencies of A-site antibiotics. Binding of an antibiotic to the 50S A site may trigger two competing processes: translocation of the A-site tRNA or its dissociation from the ribosome. Indeed, when we measured retention of A-site tRNA using a filter binding assay, dissociation of N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe from the A site was observed for 30%–40% of ribosomes after incubation of pre-translocation ribosome complexes with lincomycin or clindamycin (Fig. 7). The translocation potency of puromycin may also be affected by the ribosome-catalyzed transpeptidation reaction between peptidyl-tRNA bound to the A/P hybrid state and puromycin itself, which results in deacylation of peptidyl-tRNA. However, this is unlikely to be the main factor determining the low translocation potency of puromycin, since previous experiments have shown that it reacts poorly with the peptidyl-tRNA analogs used in this work (such as NAc-Phe-tRNAPhe and NAc-Tyr-tRNATyr), bound to the A site of pre-translocation ribosomes (Moazed and Noller 1989; Spiegel et al. 2007).

FIGURE 7.

Dissociation of N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe from the A site in the presence of peptidyl-transferase inhibitors. Pre-translocation ribosomes were assembled by binding deacylated tRNAMet to the P site and the peptidyl-tRNA analog N-Ac-[3H]Phe-tRNAPhe to the A site in the presence of mRNA, as in Figure 2A, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with sparsomycin, lincomycin, clindamycin, or chloramphenicol, as indicated. Histograms show the percentage of N-Ac-[3H]Phe-tRNAPhe bound to the A site relative to that in ribosomes untreated with antibiotics. The amount of Ac-[3H]Phe-tRNAPhe bound to the ribosome was detected by a filter-binding assay. Sparsomycin slightly stabilizes binding of Ac-[3H]Phe-tRNAPhe to post-translocation ribosomes in comparison to ribosomes untreated with antibiotics.

Despite differences in translocation efficiency, A-site-binding antibiotics evidently promote translocation. Although the ability to induce translocation is unlikely to contribute to the antimicrobial activity of these antibiotics, which are known to be potent inhibitors of the peptidyl-transferase activity of the ribosome, the phenomenon of antibiotic-induced translocation provides an important insight into the mechanism of ribosome translocation. Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that they induce translocation by sterically blocking the reverse movement of peptidyl-tRNA from the hybrid A/P to the classical A/A state as the ribosome spontaneously fluctuates between the rotated and nonrotated conformations. The antibiotics blasticidin S and erythromycin, which bind in the peptidyl transferase cavity but do not occupy the A site, do not induce mRNA translocation (Figs. 1, 2). A-site binding antibiotics that predominately clash with the aminoacyl moiety of the A-site tRNA failed to induce translocation of deacylated A-site tRNA (Fig. 3). Furthermore, isomerization of the sulfur-rich tail of sparsomycin, which interacts with the 50S A site, was recently shown to significantly decrease the ability of sparsomycin to induce translocation (Li et al. 2011). Thus, our results support the idea that the ribosome is a Brownian ratchet machine whose spontaneous fluctuation can be rectified into translocation by ligand binding.

Although EF-G accelerates translocation by 103-fold to 104-fold more than the A-site antibiotics (Rodnina et al. 1997), it may operate through an analogous mechanism, serving as a pawl in a Brownian ratchet mechanism (Frank and Gonzalez 2010; Ratje et al. 2010). Indeed, in cryo-EM reconstructions of EF-G–ribosome complexes (Valle et al. 2003; Ratje et al. 2010), as well as in a recent crystal structure of EF-G bound to a nonrotated, classical-state ribosome (Gao et al. 2009), domain IV of EF-G, which has been shown to be essential for catalysis of translocation (Rodnina et al. 1997; Martemyanov et al. 1998), overlaps with the A site of the small ribosomal subunit. Thus, one role of domain IV of EF-G could be to prevent the return of tRNA back into the 30S A site during translocation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of ribosomes and ribosomal ligands

tRNAPhe , tRNATyr, and tRNAMet were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N-Ac-Phe-tRNAPhe and EF-G with 6-histidine tag were prepared and purified as previously described (Moazed and Noller 1989; Wilson and Noller 1998; Dorner et al. 2006). Tight-couple 70S ribosomes and ribosomal subunits were prepared from Escherichia coli MRE600 as previously described (Lancaster et al. 2002; Hickerson et al. 2005). Cy5-labeled protein S6 was incorporated into 30S subunits by in vitro reconstitution from purified 16S rRNA and the other 19 individually purified ribosomal proteins according to published procedures (Culver and Noller 1999; Hickerson et al. 2005). Cy3-labeled protein L9 was incorporated into 50S subunits by partial reconstitution from 50S subunits carrying an L9 deletion, and doubly labeled 70S ribosomes were isolated using previously described procedures (Ermolenko et al. 2007a). The components of the oxygen-scavenging system (glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger, glucose, and 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Catalase from beef liver was from Roche.

Toeprinting analysis

Toeprinting experiments were performed as previously described (Fredrick and Noller 2002; Spiegel et al. 2007). The pre-translocation complex was assembled by incubating 70S ribosomes (1 μM) with deacylated tRNA (2 μM) and mRNA (2 μM) pre-annealed to [32P]-labeled primer (Fredrick and Noller 2002) in buffer A containing 30 mM HEPES·KOH (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl, and 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 20 min at 37°C. A-site tRNA (2 μM) was added to P-site tRNA-bound complexes followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. Ribosomal complexes were diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 μM with buffer A lacking MgCl2 to adjust Mg concentration to 10 mM. Translocation was carried out by incubation of pre-translocation complexes with A-site binding antibiotics or 1.5 μM EF-G and 0.5 mM GTP (Figs. 2, 3) for 20 (Fig. 1C) or 30 (Figs. 2–4) min at 37°C. The concentration of sparsomycin was 0.5 mM; all other A-site binding antibiotics were 5 mM. The position of the ribosome along the mRNA was monitored using a primer-extension reaction as described previously (Fredrick and Noller 2002). In the experiments from Figure 4A, pre-translocation ribosomes were pre-incubated with the antibiotics viomycin (1 mM) or hygromycin B (1 mM). Viomycin (1 mM) was used to stop the translocation reaction in kinetic experiments (Fig. 4C).

smFRET data acquisition and analysis

Ribosomal complexes were constructed in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES KOH (pH 7.5), 6 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM spermidine, and 0.1 mM spermine. Ribosome P-site tRNA mRNA complexes were constructed by incubation of 70S ribosomes (0.3 µM) with mRNA m301 (0.6 μM) pre-annealed to biotin-labeled primer (0.8 µM) and tRNATyr (0.7 µM) for 20 min at 37°C. All complexes were subsequently diluted to a final concentration of ∼2 nM and were immobilized on the quartz surface of microscope slides prepared for these experiments using an established protocol (Zhuang et al. 2000). To prevent photobleaching during data acquisition, the sample buffer was exchanged for imaging buffer, containing an oxygen scavenging system (20 mM HEPES KOH at pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM spermidine, 0.1 mM spermine, 0.8 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.625% glucose, ∼1.5 mM 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic [Trolox] and 0.03 mg/mL catalase) (Rasnik et al. 2006). Data were acquired and analyzed as previously described (Cornish et al. 2008). The time binning of the data was set at 100 msec. The resultant image files were processed using IDL software and analyzed using MatLab. Time traces were selected from the data set by choosing only traces that contained single photobleaching steps for Cy3 and Cy5. Furthermore, fluorescence blinking events, although extremely rare, were removed by truncating the traces prior to the blinking event. Histograms were created from the selected traces and smoothed with a 5-point window. Histograms were fit to Gaussian distributions using Origin. The peak position was left unrestrained. HaMMy was used for Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM) analysis of the FRET data (McKinney et al. 2006).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Culver and A. Korostelev for helpful discussions. These studies were supported by grants from the US National Institute of Health no. GM-099719 (to D.N.E.), P30 GM092424 (to the Center for RNA Biology at University of Rochester), and GM-17129 (to H.F.N.). Single-molecule experiments were supported in part by the National Science Foundation Physics Frontiers Center Program through the Center for the Physics of Living Cells (no. 0822613). T.H. is an employee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author contributions: D.N.E. conceived the idea. D.N.E. and H.F.N. designed the research. D.N.E. carried out biochemical experiments. P.V.C. and D.N.E. did single-molecule experiments and analyzed the data. D.N.E. and H.F.N. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agirrezabala X, Lei J, Brunelle JL, Ortiz-Meoz RF, Green R, Frank J 2008. Visualization of the hybrid state of tRNA binding promoted by spontaneous ratcheting of the ribosome. Mol Cell 32: 190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RL Jr, Puglisi JD, Chu S 2004. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 12893–12898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovinskaya MA, Shoji S, Fredrick K, Cate JH 2008. Structural basis for hygromycin B inhibition of protein biosynthesis. RNA 14: 1590–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley D, Innis CA, Blaha G, Steitz TA 2010. Revisiting the structures of several antibiotics bound to the bacterial ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 17158–17163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celma ML, Monro RE, Vazquez D 1971. Substrate and antibiotic binding sites at the peptidyl transferase centre of E. coli ribosomes: Binding of UACCA-Leu to 50 S subunits. FEBS Lett 13: 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras A, Vazquez D 1977. Cooperative and antagonistic interactions of peptidyl-tRNA and antibiotics with bacterial ribosomes. Eur J Biochem 74: 539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish PV, Ermolenko DN, Noller HF, Ha T 2008. Spontaneous intersubunit rotation in single ribosomes. Mol Cell 30: 578–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver GM, Noller HF 1999. Efficient reconstitution of functional Escherichia coli 30S ribosomal subunits from a complete set of recombinant small subunit ribosomal proteins. RNA 5: 832–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner S, Brunelle JL, Sharma D, Green R 2006. The hybrid state of tRNA binding is an authentic translation elongation intermediate. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 234–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthwaite S 1992. Interaction of the antibiotics clindamycin and lincomycin with Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 20: 4717–4720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle JA, Xiong L, Mankin AS, Cate JH 2010. Structures of the Escherichia coli ribosome with antibiotics bound near the peptidyl transferase center explain spectra of drug action. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 17152–17157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle JA, Wang L, Feldman MB, Pulk A, Chen VB, Kapral GJ, Noeske J, Richardson JS, Blanchard SC, Cate JH 2011. Structures of the bacterial ribosome in classical and hybrid states of tRNA binding. Science 332: 981–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolenko DN, Noller HF 2011. mRNA translocation occurs during the second step of ribosomal intersubunit rotation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 457–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolenko DN, Majumdar ZK, Hickerson RP, Spiegel PC, Clegg RM, Noller HF 2007a. Observation of intersubunit movement of the ribosome in solution using FRET. J Mol Biol 370: 530–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolenko DN, Spiegel PC, Majumdar ZK, Hickerson RP, Clegg RM, Noller HF 2007b. The antibiotic viomycin traps the ribosome in an intermediate state of translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei J, Kosuri P, MacDougall DD, Gonzalez RL Jr 2008. Coupling of ribosomal L1 stalk and tRNA dynamics during translation elongation. Mol Cell 30: 348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Munoz R, Monro RE, Torres-Pinedo R, Vazquez D 1971. Substrate- and antibiotic-binding sites at the peptidyl-transferase centre of Escherichia coli ribosomes. Studies on the chloramphenicol, lincomycin and erythromycin sites. Eur J Biochem 23: 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Gonzalez RL Jr 2010. Structure and dynamics of a processive Brownian motor: The translating ribosome. Annu Rev Biochem 79: 381–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrick K, Noller HF 2002. Accurate translocation of mRNA by the ribosome requires a peptidyl group or its analog on the tRNA moving into the 30S P site. Mol Cell 9: 1125–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrick K, Noller HF 2003. Catalysis of ribosomal translocation by sparsomycin. Science 300: 1159–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YG, Selmer M, Dunham CM, Weixlbaumer A, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V 2009. The structure of the ribosome with elongation factor G trapped in the posttranslocational state. Science 326: 694–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JL, Moore PB, Steitz TA 2003. Structures of five antibiotics bound at the peptidyl transferase center of the large ribosomal subunit. J Mol Biol 330: 1061–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson R, Majumdar ZK, Baucom A, Clegg RM, Noller HF 2005. Measurement of internal movements within the 30 S ribosomal subunit using Forster resonance energy transfer. J Mol Biol 354: 459–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan LH, Noller HF 2007. Intersubunit movement is required for ribosomal translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 4881–4885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J 2006. Protein power strokes. Curr Biol 16: R517–R519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Noller HF 1998. EF-G-catalyzed translocation of anticodon stem–loop analogs of transfer RNA in the ribosome. EMBO J 17: 3478–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian P, Konevega AL, Scheres SH, Lazaro M, Gil D, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina MV, Valle M 2008. Structure of ratcheted ribosomes with tRNAs in hybrid states. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 16924–16927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster L, Kiel MC, Kaji A, Noller HF 2002. Orientation of ribosome recycling factor in the ribosome from directed hydroxyl radical probing. Cell 111: 129–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro E, van den Broek LA, Ottenheijm HC, Lelieveld P, Ballesta JP 1987. Structure–activity relationships of sparsomycin: Modification at the hydroxyl group. Biochimie 69: 849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro E, van den Broek LA, San Felix A, Ottenheijm HC, Ballesta JP 1991. Biochemical and kinetic characteristics of the interaction of the antitumor antibiotic sparsomycin with prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes. Biochemistry 30: 9642–9648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Cheng X, Zhou Y, Xi Z 2011. Sparsomycin-linezolid conjugates can promote ribosomal translocation. Chembiochem 12: 2801–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AH, Murray RW, Vidmar TJ, Marotti KR 1997. The oxazolidinone eperezolid binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit and competes with binding of chloramphenicol and lincomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41: 2127–2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martemyanov KA, Yarunin AS, Liljas A, Gudkov AT 1998. An intact conformation at the tip of elongation factor G domain IV is functionally important. FEBS Lett 434: 205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney SA, Joo C, Ha T 2006. Analysis of single-molecule FRET trajectories using hidden Markov modeling. Biophys J 91: 1941–1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D, Noller HF 1989. Intermediate states in the movement of transfer RNA in the ribosome. Nature 342: 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monro RE, Celma ML, Vazquez D 1969. Action of sparsomycin on ribosome-catalysed peptidyl transfer. Nature 222: 356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro JB, Altman RB, O’Connor N, Blanchard SC 2007. Identification of two distinct hybrid state intermediates on the ribosome. Mol Cell 25: 505–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Kirillov SV, Cooperman BS 2007. Kinetically competent intermediates in the translocation step of protein synthesis. Mol Cell 25: 519–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peske F, Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W 2004. Conformational changes of the small ribosomal subunit during elongation factor G-dependent tRNA-mRNA translocation. J Mol Biol 343: 1183–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka S 1969. Studies on the formation of transfer ribonucleic acid-ribosome complexes. XI. Antibiotic effects on phenylalanyl-oligonucleotide binding to ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 64: 709–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasnik I, McKinney SA, Ha T 2006. Nonblinking and long-lasting single-molecule fluorescence imaging. Nat Methods 3: 891–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratje AH, Loerke J, Mikolajka A, Brunner M, Hildebrand PW, Starosta AL, Donhofer A, Connell SR, Fucini P, Mielke T, et al. 2010. Head swivel on the ribosome facilitates translocation by means of intra-subunit tRNA hybrid sites. Nature 468: 713–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodnina MV, Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Wintermeyer W 1997. Hydrolysis of GTP by elongation factor G drives tRNA movement on the ribosome. Nature 385: 37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlunzen F, Zarivach R, Harms J, Bashan A, Tocilj A, Albrecht R, Yonath A, Franceschi F 2001. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature 413: 814–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuwirth BS, Borovinskaya MA, Hau CW, Zhang W, Vila-Sanjurjo A, Holton JM, Cate JH 2005. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 Å resolution. Science 310: 827–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel PC, Ermolenko DN, Noller HF 2007. Elongation factor G stabilizes the hybrid-state conformation of the 70S ribosome. RNA 13: 1473–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin AS 2004. The ribosome as an RNA-based molecular machine. RNA Biol 1: 3–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley RE, Blaha G, Grodzicki RL, Strickler MD, Steitz TA 2010. The structures of the anti-tuberculosis antibiotics viomycin and capreomycin bound to the 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 289–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle M, Zavialov A, Sengupta J, Rawat U, Ehrenberg M, Frank J 2003. Locking and unlocking of ribosomal motions. Cell 114: 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DN 2009. The A–Z of bacterial translation inhibitors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 44: 393–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KS, Noller HF 1998. Mapping the position of translational elongation factor EF-G in the ribosome by directed hydroxyl radical probing. Cell 92: 131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth I, Beringer M, Rodnina MV 2006. Rapid peptide bond formation on isolated 50S ribosomal subunits. EMBO Rep 7: 699–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Lancaster L, Trakhanov S, Noller HF 2012. Crystal structure of release factor RF3 trapped in the GTP state on a rotated conformation of the ribosome. RNA 18: 230–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X, Bartley LE, Babcock HP, Russell R, Ha T, Herschlag D, Chu S 2000. A single-molecule study of RNA catalysis and folding. Science 288: 2048–2051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]