Abstract

Objective:

The research explored the roles of practicing clinical librarians embedded in a patient care team.

Methods:

Six clinical librarians from Canada and one from the United States were interviewed to elicit detailed descriptions of their clinical roles and responsibilities and the context in which these were performed.

Results:

Participants were embedded in a wide range of clinical service areas, working with a diverse complement of health professionals. As clinical librarians, participants wore many hats, including expert searcher, teacher, content manager, and patient advocate. Unique aspects of how these roles played out included a sense of urgency surrounding searching activities, the broad dissemination of responses to clinical questions, and leverage of the roles of expert searcher, teacher, and content manager to advocate for patients.

Conclusions:

Detailed role descriptions of clinical librarians embedded in patient care teams suggest possible new practices for existing clinical librarians, provide direction for training new librarians working in patient care environments, and raise awareness of the clinical librarian specialty among current and budding health information professionals.

Highlights.

The often broad dissemination of responses to clinical questions by clinical librarians contrasts with the one-to-one interactions typical of in-library reference transactions.

As team members, clinical librarians contribute expert searching, instruction, and content management skills and leverage those skills to support and advocate for patients.

Being detached from hands-on patient care may allow clinical librarians to provide an objective and valuable perspective to clinical team.

Clinical librarians perceive that their presence on wards and at team meetings enhances their visibility and understanding of clinicians' use of the information they provide.

Implications.

Based on the participants' reports, it is possible to take on a clinical librarian role in addition to other duties and to be embedded without having dedicated office space in the clinical area being served.

There is a need for additional research to confirm this study's findings with respect to information prescriptions, electronic health records, and the concept of emotional labor.

INTRODUCTION

Librarians have been supporting patient care teams in clinical settings for more than thirty years 1, 2, providing benefits to medicine such as saving clinicians' time 3, decreasing costs 4, supporting decision making 5, and improving overall patient care 6. These clinical librarians (CLs) have been cast in roles ranging from the “traditional” (such as performing literature searches and promoting library services) to less traditional, more embedded roles (such as attending case conferences and participating in patient care rounds) 1, 3, 7–10. In 2003, Winning described the CL role: “to support clinical decision-making and/or education by providing timely, quality-filtered information to clinicians at the point of need” 11. Later CL characterizations have expanded to include performing critical appraisals and outreach activities such as participating in team discussions, ward rounds, and journal clubs 12, 13. A scan of the Medical Library Association's jobs web page <http://www.mlanet.org/jobs/> in March 2012 revealed that many libraries were hiring CLs. For example, Stanford University Lane Medical Library recently advertised a position in which the successful applicant would spend the majority of his or her workday embedded within a patient care team. In this role, the CL would accompany physicians on daily patient care bedside rounds, provide information literacy training based on patient care questions, and attend team meetings.

A great deal has been written about clinical librarianship and captured in systematic reviews 7, 11, 12, 14. This literature predominantly takes a quantitative approach to the study of clinical librarianship, providing broad concept models of CL programs and evidence regarding their effectiveness. Other publications describe CL roles based on survey data or report on a specific program employing a CL 15, 16. However, this literature does not provide those interested in CL positions, or those who wish to hire CLs, with the benefits of a qualitative approach, designed to depict how individuals experience and interact with their social worlds 17.

A current review of the CL literature revealed only a handful of qualitative studies. Harrison interviewed five CLs using a semi-structured protocol to determine CL roles in the United Kingdom 18. Harrison's interview questions focused on core duties, available training, key skills, and service promotion. From this exploration, Harrison generated a qualitative report 19, supported by insightful quotes from participants, that provided a portrait of CLs' “lived experiences” 18. In 2009, Robison gathered qualitative data on health researchers' and clinicians' perceptions of informationists with whom they worked in the field of clinical research 20. According to participants, the informationist was seen as part of the research team and provided resource identification and instruction. More recently, in Sweden, Määttä described a CL program aimed at assisting nurses to procure evidence-based nursing skills, including results from interviews with two CLs and from focus groups conducted with fifteen nurses 21. Although this account focused primarily on the perspective of nurses and provided limited insight into the CL position, the reflections of the CLs revealed three themes: “to be an outsider,” “to acquire new knowledge,” and “to acquire a new role.”

The purpose of the present study was to characterize the roles and responsibilities of North American CLs today. The guiding research question was: What does the role of a clinical librarian embedded in a patient care team look like?

METHODS

A definition of clinical librarian for the purposes of this study was created by: (1) reviewing the existing CL literature and (2) communicating informally with individuals in the health librarian community. Based on this analysis, CLs were defined as individuals with a library science degree who, in the context of a patient care team, provide customized services to meet information needs related to patient care. CLs may attend hospital rounds, journal clubs, or other health care team meetings. These individuals have responsibilities beyond those of a general hospital librarian and beyond providing traditional reference and document delivery services. For the purpose of this study, CL was used as an encompassing term that included synonyms such as clinical informationist and patient care librarian.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta. In July and August 2011, 7 information professionals working in Canada (n = 6) and the United States (n = 1) who fit the above CL definition were interviewed by telephone about their clinical roles. A convenience sample of participants was recruited through posting to health librarian email discussion lists and discussion forums (n = 4); networking at professional meetings and with known CLs (n = 2); consultation with an expert in the area of clinical librarianship (n = 1); and snowball sampling (n = 2). A single CL was known to author Maggio but not to Tan, the interviewer. The invitation to participate included the CL definition mentioned above and a request to share experiences about their CL roles and responsibilities. Of the 9 individuals who volunteered to participate, 2 were excluded because they did not work on a patient care team and failed to meet the CL definition used for this study. The remaining 7 CLs completed the study.

Data collection

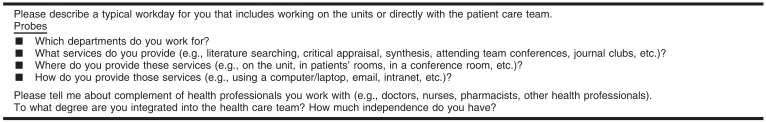

Each participant was interviewed once by telephone for forty-five to sixty minutes. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured protocol (Figure 1) that began with the question, “Please describe a typical workday for you that includes working on the units or directly with the patient care team.” When necessary, question probes—such as, “Can you tell me a little bit more about where [rounds] take place?”; “Approximately how many people are on the team that you work with?”; and “How do you communicate search results to the team?”—were used to clarify details related to the physical environment, complement of team members, specific activities, and procedures. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1.

Interview guide

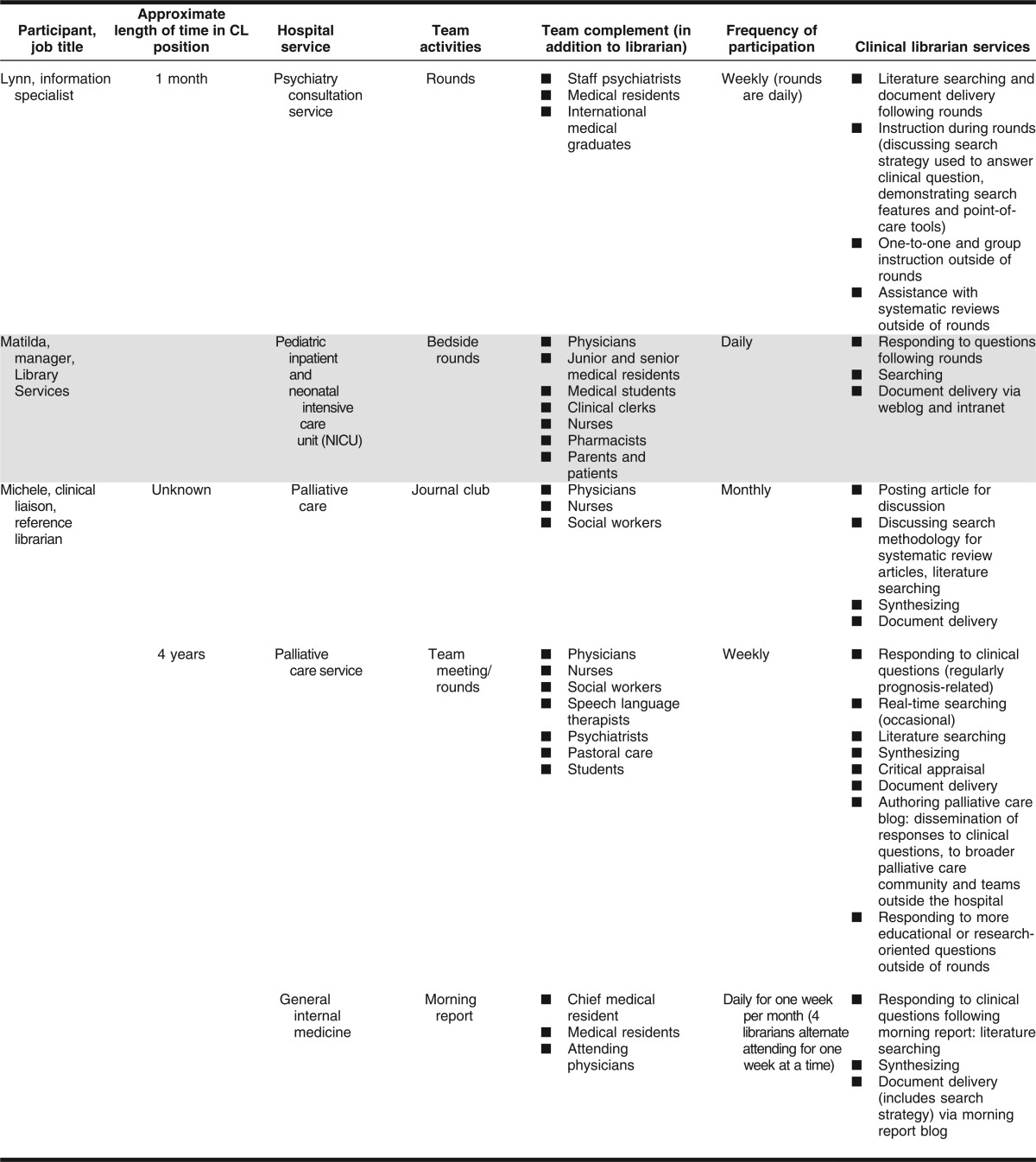

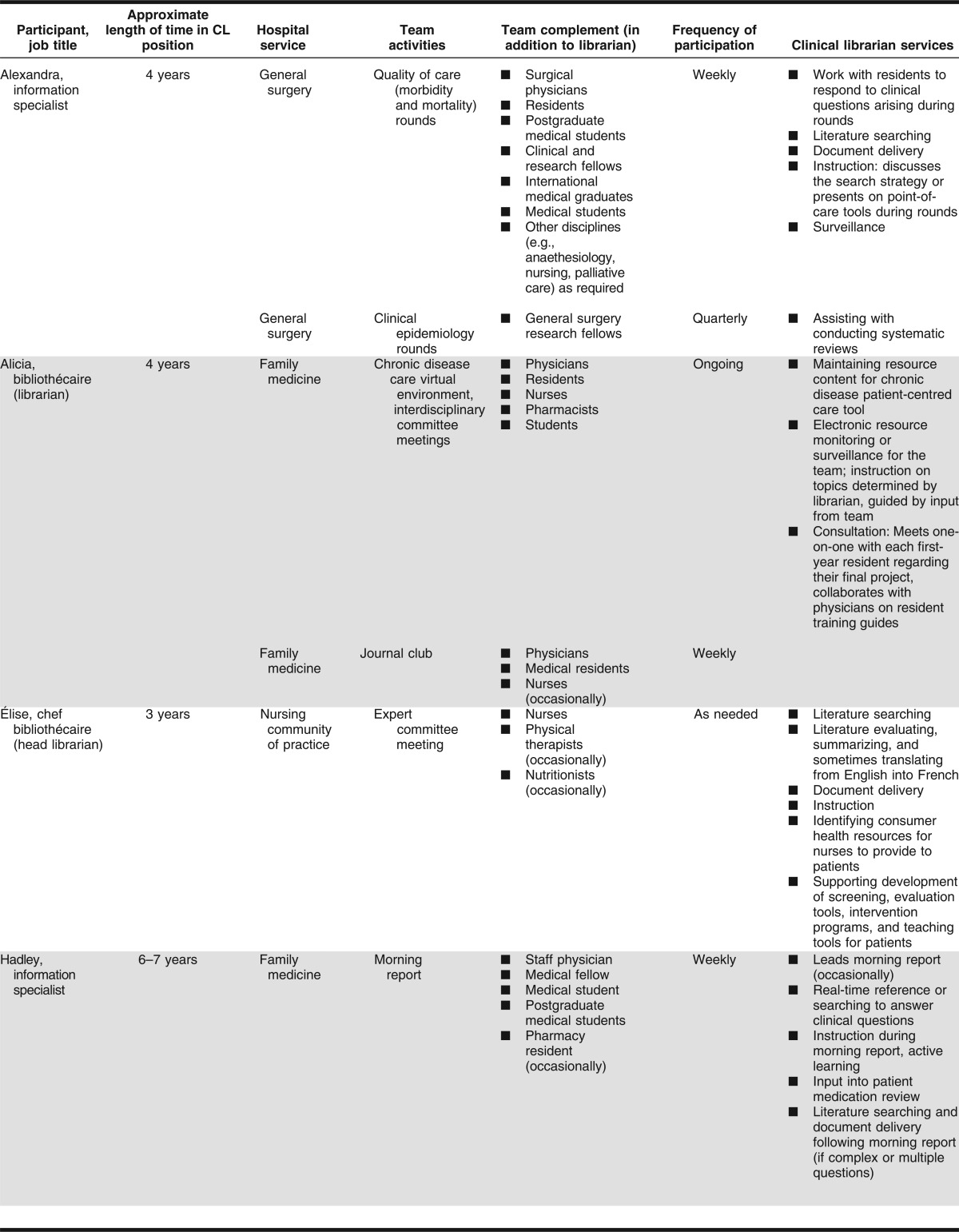

Table 1.

Continued.

Data analysis

The first author used an open-coding approach to identify general themes emerging from the data. Each transcript was reviewed to identify passages relevant to the research question. Quotes were extracted from these relevant passages and organized into general categories (e.g., clinical activities, degree of integration). Broad descriptive categories such as “Activities” were subdivided into specific activities (e.g., morning report, journal club). These qualitative data were synthesized into a profile, relying heavily on paraphrases and quotes to accurately represent the participants' portrayal of their clinical roles. Lastly, elements from all profiles were summarized in a table to allow for easier identification of trends and unique features. Email follow up with five participants helped to clarify or expand aspects discussed in the initial interview, and follow-up data were incorporated into participant profiles. The other two participants' responses did not require clarification. Maggio and a faculty advisor reviewed each de-identified participant's transcripts, extracted quotes, general categories, and profiles. Agreement about themes was achieved through discussions among all three researchers.

To ensure the reliability and validity (or confirmability and credibility) of the research, several approaches were undertaken, including (1) documenting in detail the research process and results, (2) using iterative data analysis involving both authors and an external advisor, (3) following up with participants for clarification of their responses throughout and after the interview process (a form of member-checking), (4) developing participant profiles to highlight data relevant to the research question while preserving the context, and (5) integrating qualitative data (participant's words) into results and discussion so that findings and interpretations could be traced to the source.

RESULTS

This section provides an overview of participant characteristics, then focuses on four roles that emerged as themes from participant interviews: expert searcher, teacher, content manager, and patient support or advocate. Each theme is presented with supporting quotations, credited to each participant.

Study participants

To maintain confidentiality, all participants are identified by pseudonyms of their own choosing. Characteristics of the participants including job titles, settings in which participants performed their clinical roles, patient care team composition, and CL services provided are detailed in Table 1. Coincidentally, all participants worked at university-affiliated teaching hospitals. They were embedded in a range of health care specialties including family medicine, pediatrics, surgery, and psychiatry. None of the participants had an office or permanent work space within the specific unit or program to which they provided clinical librarian services. They joined their teams in team conference rooms, in the physicians' offices, or on patient care units to participate in patient care rounds, morning report, journal clubs, and committee meetings. Two participants mentioned that they bring mobile devices with them to use during team activities. Following team meetings or activities, participants returned to their home bases at their libraries to follow up on work arising from team interactions. Most teams comprised primarily physicians and medical trainees, with representation from at least one other health discipline (e.g., social work, rehabilitation medicine, pastoral care). Although six of the seven participants' job titles did not reflect the clinical aspect of their position or relationship with clinical care, participants self-described their clinical identity as “clinical librarian” or “informationist” or referred to the “clinical component” of their positions.

Table 1.

Summary of participant characteristics, hospital service, team complement and activities, and clinical librarian (CL) services

Librarian as expert searcher

For all participants, literature searching was a major component of their clinical role. Searches were undertaken predominantly to support clinician information needs. Participants received as many as ten questions per day from team members during the course of rounds and other activities. In some cases, the CLs were assigned a single question per team interaction; others routinely received multiple questions across a variety of topics. Drug interactions, disease prognosis, and critical appraisal of search methodology in systematic reviews were common question types. Non-patient-specific requests related to finding images for resident presentations and contributing to systematic reviews. According to four participants, being on the unit with clinicians appeared to be a stimulus for additional reference questions. For example, participant Alexandra said that when the senior surgeons see her at rounds they approach her with additional requests.

Participants noted that searches were initiated during or shortly after team meetings. Response time ranged from a few minutes to forty-eight hours. Two participants regularly conducted searches on the fly during team activities. For example, Hadley explained that during morning report, “Everything is done in real time, so I don't know what the questions are going to be, and [you're] kind of flying by the seat of your pants seeing what you can get done in the time they've given you.” Michele, in her interview, elaborated on the time-sensitivity of some of the CL responses to the team's clinical questions: “Particularly if I see it's going to change care, and it's a pivotal piece of information, I will page them and say ‘I have sent this to you, so you might want to take a look at this.’”

Librarian as teacher

Instruction was an integral part of many, but not all, participants' interactions with the patient care team. Three participants had “structured teaching time” carved out during team rounds and journal clubs, during which they would engage the team in a dialogue about the searching process or demonstrate relevant resources, such as point-of-care tools. During rounds with the psychiatry consult team, Lynn “show[ed] them why it's good to search one database at a time because the subject headings are different depending on which database you use.” Hadley actively engaged learners during morning report: Her aim was to nurture an understanding of the search process by having medical residents or students come up to the computer to “show us what they would do and I…give suggestions as to how to improve this type of a search.” Other participants took part in instruction planning activities. As examples of other teaching roles, Alicia collaborated with a physician on a resident training guide and Élise worked with nurses to prepare professional development materials for adopting best practices. Meeting one-to-one or in small groups with health practitioners and clinical residents to support their research and learning needs was also common practice. Training topics included, but were not limited to, database searching, critical appraisal, how to read a scientific paper, interpretation of copyright policies, and reference management strategies.

Michele stated that her clinical role did not include an instructional mandate. Both she and Matilda, another participant, appeared to have more of a consultative role on the ward. However, both incorporated instruction informally (e.g., sharing search strategies upon request, explaining their decision-making process when commenting on the strength of a search method in a scholarly article). Matilda also posted training tips on the staff intranet in response to frequently asked questions.

Librarian as content manager

Content management activities common to all participants were: identifying, selecting, and disseminating information in response to patient-related questions. Additional responsibilities for some participants included summarizing, synthesizing or critically appraising literature, and surveying information. For one librarian, translating content from one language to another and transforming research information into plain language resources for patients and families were parts of her content management role. Another participant, Alicia, maintained and updated a collection of information for clinicians and patients in an online clinical care tool. This “virtual library” was accessed continuously by the family medicine team for patient assessment, clinical decision making, and documentation of patient care. Alicia explained, “It's an IT [information technology] tool so we have to find the right answer for different questions that [clinicians] ask…For example, if a doctor…sees a patient is hypertensive, what does he have to ask him, what does he have to think about for the patient? It has to be inside this tool.”

A notable aspect of participants' content management activities was the broad dissemination of responses to clinical questions. Participants leveraged a wide range of communication strategies to facilitate timely and widespread dissemination of relevant information to clinicians. Responses to clinical questions arising in care team situations were shared in team venues (e.g., rounds) and sometimes with the clinical community at large. This broad dissemination contrasts with the one-to-one interactions typical of in-library reference interactions. Results of literature searches were communicated to team members via email, presented verbally at rounds or morning report, or shared via social media applications. Participants employed blogs, microblogs, staff intranets, social bookmarking applications, and Twitter to deliver search results to their teams, to post articles for journal club discussions, and to disseminate relevant and timely resources from information surveillance activities. Examples of participants' applications of social media in the clinical setting included: using a Tumblr microblog to communicate responses to questions that arise during rounds, setting up Google Custom Searches to help users search for and access relevant clinical content on the staff intranet, and using a team blog to post articles and supplementary materials for journal club discussions. In Michele's case, information sharing extended beyond the in-house clinical team. She explained how responses to patient care questions are shared with the broader palliative care community:

I would blog relevant questions and answers if the requester consents…I send it out not just to our local team but there's a whole directory of palliative care personnel and they are located at several hospitals and they are also located at the community family hospice in the area. So it goes out to the palliative care teams at other hospitals and to community health care professionals working with us. So it's a pretty unique and wide distribution.

Librarian as patient support or advocate

Some participants leveraged the roles of expert searcher, teacher, and content manager to support and advocate for patients. To some degree, CL participants also leveraged their detachment from the direct hands-on care of the patient to provide a different but valuable viewpoint of the experience. For example, because Hadley, was “not of that department but I'm included in that department,” she found that she picked up things during patient medication reviews at morning report that other team members “might not notice because it's not the primary complaint,” and she felt comfortable prompting the team about her observations.

In another example of patient advocacy, Élise described how she opened a patient and family library in the hospital and collaborated with physicians on what she calls “information prescriptions.” These “prescriptions” are written by the doctor or specialist and are used to direct the patient to the library and to guide the librarian about the genre of information to provide the patient: “I ask the doctor to give me some directive, to say what the patient expect[s] to receive from me or the library…It could be to ask for a general book on the subject, [or] to do some search in PubMed or MEDLINE.” Élise initiated this stage of integrating the librarian into the patient care team to enhance patients' capacity to make informed health decisions. She asserts: “How can we empower the patient if we can't give them any information? That's why I thought about [making] the information available to them, because you can't decide when you don't have the information.”

Playing a dual role of serving clinicians and providing consumer health information to the team's patients and families appeared to add an element of complexity to some CLs' jobs. In Matilda's situation, pediatric patients and sometimes parents are present during ward rounds in the patients' rooms. Matilda is dedicated to directly serving the medical team and does not encourage questions from families: “[When] the medical team goes around to the patients' rooms…I usually wait and not bring my stuff up when the parents are involved—and they don't get the chance to ask me directly for information. We do have a consumer health library and they can come down there and ask, but I don't…solicit from them ‘what do you want.’” When parents visit the consumer health library, Matilda is cautious about not biasing her response based on what she knows about the team's treatment approach: “I know that the team seems to be in a different direction perhaps, than what the parents are asking about, so then I have to be very careful just to deal with the parents' request as is, and not sort of steer things at all and kind of let that understanding of what's happening unfold without much intervention from me.”

Integration of clinical librarians into patient care teams

All seven participants reported feeling that they were part of the patient care team. Some indicated that they were deeply integrated with the team, which was supported by their access to areas of the patient care unit and their involvement in social and milestone events. Hadley reported, “I can't imagine what more—apart from having an office in that particular vicinity—what more integration could be involved.” Michele echoed this with her statement: “I feel, if I had to quantify it, I would say I'm integrated [into] about 80% of the activities. I do everything but go eye-to-eye with patients.” By being embedded in the patient care team environment, Matilda said, “I have an infinitely better understanding of the context, the situation where they're [clinicians are] actually using the information.” The participants' believed their presence on the wards and at team meetings enhanced their visibility, improved clinicians' access to timely CL services, and provided opportunities for additional conversations, consultations, and collaborations outside formal team activities. Being embedded into the patient care team enabled CLs to carry out their expert searching, instructional, knowledge management, and patient advocacy roles in an optimal fashion. As one participant, Matilda, summed it up:

Certainly [being at rounds,] it's a tremendous chance to get to know all the residents during their training. Enormously improves my visibility—even if they don't know my name they know [I'm] the librarian. There's no way that would happen if I sat in my office.

One participant expressed concerns about the lack of a work space in proximity to the team: Alicia stated, “I would feel more integrated if I would be able to have a couple of hours in…the family medicine unit…I know that I'm missing things because I'm out of this office.” Another participant, Michele, hinted that the patient care team's perception of the CL role as expert searcher might be swayed because of her nursing background: “I'm the first person who was invited to join the journal club…it was [because of] my clinical credentials they, rightfully, decided I was a good person for it.”

Several of the participants described the affective component of their work in a patient care setting, a topic explored by Lyon 22. Some of these experiences appeared to be unique to librarian responsibilities in a clinical environment. For example, one participant, Alexandra, described the emotions surrounding viewing surgical procedures:

It can be kind [of] gruesome though, I have to admit. Part of the problem I find is that I'm not desensitized to some of the stuff. For example, all of the laparoscopic surgeries are now videorecorded. So they'll actually show when things go wrong [laughs]…I can't watch them cut—I can't watch the initial—like when they're putting in the trocars and stuff. I am getting much better, but initially, for the first little while—occasionally I go home crying—it can be that intense…I'm much better now but at the beginning I did find it very difficult, and it really was a challenge.

DISCUSSION

This exploration of CL roles yielded findings that support and contrast with existing literature. The lack of a consistent title for the clinical role appears to be an ongoing issue 1, 11, 17. One possible reason that this study found, as did Ward, was that clinical duties were just one aspect of our participants' overall positions 15.

As in previous studies, literature searching emerged as a strong theme among participants in our study of CL roles. This activity has been consistently given high priority by both CLs and users 1, 15, 23, 24. Harrison and Beraquet found that the twenty-six CLs they surveyed reported spending the largest fraction of their hours on literature searching, and those authors considered literature searching a core activity in their CL model 1. The sense of urgency that accompanied literature searching found in our study did not seem to be as well described in other published reports of CL activities in the patient care environment. This notion, however, has been discussed in the special libraries literature, especially in corporate settings 25.

Participants in the current study engaged in a broad range of teaching activities for the patient care team, from formal instructional sessions to informal consultative activities. In addition to search-skills training, study participants taught team members about critical appraisal, interpretation of copyright policies, reference management strategies, and point-of-care tool use. This contrasted with CLs in the United Kingdom, for whom instruction, limited specifically to search-skills training, ranked fourth of seven activities in terms of hours spent 1. All participants in our study worked at teaching hospitals, where a large proportion of the clinical clientele base was residents and other trainees, which might account for the emphasis on instruction observed with our sample.

Recently, Damani and Fulton described CL experiences using Web 2.0 tools to disseminate evidence-based literature to patient care teams in one American institution 26. The authors highlighted challenges of Web 2.0 adoption, but also recognized the potential for using social media to better serve clinicians at the point of need. Our study findings suggested that CLs were successfully leveraging social media tools in their clinical environments to disseminate timely and relevant information to the immediate patient care team and to the team's network of health professionals who provided support in the community.

Some themes emerging from our study did not appear to have been reported in existing literature. Further research to confirm their importance would be valuable. For example, little has been published on the role of CLs in using electronic health records (EHRs) in their work 27, a concept that was envisioned a number of years ago 28. Although none of our participants used EHRs in their work, their reported experiences as content managers and knowledge translators hinted at the potential contribution of CLs to this area. Also, while physician-directed information prescriptions guiding patients to online health information sources have been reported 29, physician-librarian collaboration on information prescriptions for patients and families as described by a participant in our study went beyond this approach. Physicians referring a patient to the CL who searched for and vets the information in digital or print formats for the patient resembled Vanderbilt University's Patient Informatics Consult Service 30. Simultaneously serving both patients and physicians, as reported by some CLs in this study, and—with the exception of tangential results in the research of Marshall 31 and Robison 20—the perceived degree of integration or embeddedness of the clinical librarian were two other aspects of clinical librarianship not reported elsewhere. Given the minimal literature exploring CL roles in Canada, this study brings attention to the presence of CLs in Canada and provides a stepping-stone for further investigation on CL roles from a Canadian perspective. The influence of credentials on CL role, responsibilities, and integration with health care teams was raised. Although this topic has been broached indirectly in relation to the informationist role 22, current coverage directly tied to CL and health care provider perspectives could provide valuable insights.

Related to the multifaceted CL role, a finding of this study was that our participants did not view their lack of office space in the patient care setting as a major barrier to their embeddedness on the patient care team. Participants engaged in diverse activities and carried out their CL duties in a various ways, even in the same institution. This finding is a reminder for CL and library administrators that there is no “one size fits all” approach to being a CL and suggests the shortcomings of making assumptions about which specific activities—such as rounding with teams, facilitating morning report, providing materials for journal clubs, and so on—will be most desired by, and useful to, the clinical department to which the CL is assigned. There may be a tendency to cast the CL presence in hospital rounds as the ultimate indicator of CL embeddedness. Medical library leaders should bear in mind that this is just one approach and that there is a need to create and maintain robust communication channels to best understand the needs of the clinical department.

Managing emotions when performing CL duties and the tension described earlier by some participants who worked with both clinicians and their patients resonated with the sociological concept of “emotional labour” that has been examined in information literacy instruction research 33. Librarians interested in pursuing clinical librarianship need to be aware of this potential occupational stressor. It is also critical that resources such as those offered to health professionals are made readily available to support the emotional well-being of CLs.

Limitations of the study

All participants were volunteers, which might have led to an over-representation of CL “success stories.” It is possible that CLs who have had negative experiences were less likely to volunteer. Data on CL roles were collected solely from the CL perspective and only through interviews. Additional sources of data, such as directly observing CLs in patient care settings and surveying health care team members about their perceptions of the CL role, might provide a more complete picture. Generalizability is limited by the small sample size and geographical limitations; however, the data emerging from this study warrant further exploration.

CONCLUSION

Using a qualitative lens to examine CL roles yielded data about the varied contexts in which these information professionals work, the key roles CLs may play, and current CL practices they employ to support clinicians' information needs. These detailed descriptions of the CL role embedded in patient care teams suggest possible new practices for current CLs, provide some direction for training new librarians working in patient care environments, and can raise awareness of this specialty among current and budding health information professionals. Our study also reinforces the findings of others that clinical duties may constitute only one component of CL positions and that the majority of participants also engage in other duties unrelated to their CL role.

Findings from this study add to the existing body of literature on clinical librarianship and reveal themes for further exploration, including the affective nature of clinical librarianship, the potential dual roles of librarian as patient advocate and clinician support, the ability of CLs to widely and efficiently disseminate information, and the time-sensitivity of CL response to information requests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ann Curry who advised on our research study and contributed to the manuscript. Thank you also to Dr. Shelagh Genuis and to Blair Anton for reviewing the manuscript. We also express our appreciation to our study participants for their valuable time and input.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrison J, Beraquet V. Clinical librarians, a new tribe in the UK: roles and responsibilities. Health Inf Lib J. 2010 Jun;27(2):123–32. doi: 10.1111/2Fj.1471-1842.2009.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipscomb CE. Clinical librarianship [historical notes] Bull Med Lib Assoc. 2000 Oct;88(4):393–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makowski G. Clinical medical librarianship: a role for the future. Bibl Medica Canadiana. 1994;16(1):7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urquhart C, Durbin J, Turner J. North Wales clinical librarian project [Internet] Aberystwyth, UK: University of Wales, Department of Information Studies; May 2005 [cited 14 May 2012]. < http://www.dils.aber.ac.uk/dis/research/reports/nwalesclinlibproject_report.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aitken EM, Powelson SE, Reaume RD, Ghali WA. Involving clinical librarians at the point of care: results of a controlled intervention. Acad Med. 2011 Dec;86(12):1508–12. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823595cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulvaney A, Bickman L, Giuse N, Lambert W, Sathe N, Jerome R. A randomized effectiveness trial of a clinical informatics consult service: impact on evidence-based decision-making and knowledge implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008 Mar/Apr;15(2):203–211. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimpl K. Clinical medical librarianship: a review of the literature. Bull Med Lib Assoc. 1985 Jan;73(1):21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargeant SJE, Harrison J. Clinical librarianship in the UK: temporary trend or permanent profession? part I: a review of the role of the clinical librarian. Health Inf Lib J. 2004 Sep;21(3):173–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2004.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwing LJ, Coldsmith EE. Librarians as hidden gems in a clinical team. Med Ref Serv Q. 2005;24(1):29–39. doi: 10.1300/J115v24n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Miller MD, Wilder KS, Martin SL, Sathe NA, Campbell JD. Clinical medical librarianship: the Vanderbilt experience. Bull Med Lib Assoc. 1998 Jul;86(3):412–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winning MA, Beverley CA. Clinical librarianship: a systematic review of the literature. Health Inf Lib J. 2003 Jun;20(suppl s1):10–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.20.s1.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brettle A, Maden-Jenkins M, Anderson L, McNally R, Pratchett T, Tancock J, Thornton D, Webb A. Evaluating clinical librarian services: a systematic review. Health Inf Lib J. 2011 Mar;28(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2010.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill P. Report of a national review of NHS funded library information services in England: from knowledge to health in the 21st century [Internet] Warwick, UK: National Institute for Innovation and Improvement; p. 107. Mar 2008 [cited 14 May 2012]. < http://www.healthlinklibraries.co.uk/pdf/National_Library_Review_Final_Report_4Feb2008.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner KC, Byrd GD. Evaluating the effectiveness of clinical medical librarian programs: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Lib Assoc. 2004 Jan;92(1):14–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward L. A survey of UK clinical librarianship: February 2004. Health Inf Lib J. 2005 Mar;22(1):26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2005.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greco E, Englesakis M, Faulkner A, Trojan B, Rotstein LE, Urbach DR. Clinical librarian attendance at general surgery quality of care rounds (morbidity and mortality conference) Surg Innov. 2009 Sep;16(3):266–9. doi: 10.1177/1553350609345487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merriam S. Qualitative research in practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 3–17. Chapter 1, Introduction to qualitative research; [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison J, Sargeant SJE. Clinical librarianship in the UK: temporary trend or permanent profession? part II: present challenges and future opportunities. Health Inf Lib J. 2004 Dec;21(4):220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2004.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker H. The epistemology of qualitative research. In: Jessor R, Colby A, Schweder R, editors. Ethnography and human development. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 1996. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robison RR, Ryan ME, Cooper ID. Inquiring informationists: a qualitative exploration of our role. Evid Based Lib Inf Pract. 2009;4(1):4–16. doi: 10.18438/b8t03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Määttä S, Wallmyr G. Clinical librarians as facilitators of nurses' evidence-based practice. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Dec;19(23/24):3427–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyon JA, Ferree N, Butson LC, Moeller K, Summey K. Scared and squeamish: identifying fears and barriers to providing information services in the real world of rounding [Internet] Paper presented at: MLA ’11, 111th Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; Minneapolis, MN; 13–18 May 2011 [cited 14 May 2012]. < http://www.mlanet.org/am/am2011/pdf/mla11_abstracts.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tod AM, Bond B, Leonard N, Gilsenan IJ, Palfreyman S. Exploring the contribution of the clinical librarian to facilitating evidence-based nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Apr;16:621–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brookman A, Lovell A, Henwood F, Lehmann J. What do clinicians want from us? an evaluation of Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust clinical librarian service and its implications for developing future working patterns. Health Inf Lib J. 2006 Dec;23(suppl s1):10–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2006.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rimland E, Masuchika G. Transitioning to corporate librarianship. J Bus Fin Lib. 2008;13(3):321–34. doi: 10.1080/08963560802183302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damani S, Fulton S. Collaborating and delivering literature search results to clinical teams using Web 2.0 tools. Med Ref Serv Q. 2010;29(3):207–17. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2010.494476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barron S, Manhas S. Electronic health record (EHR) projects in Canada: participation options for Canadian health librarians. J Can Health Lib Assoc. 2011;32(3):137–43. doi: 10.5596/c11-044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert K. Integrating knowledge-based resources into the electronic health record: history, current status, and role of librarians. Med Ref Serv Q. 2007 Fall;26(3):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J115v26n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coberly E, Boren SA, Davis JW, McConnell AL, Chitima-Matsiga R, Ge B, Logan RA, Steinmann WC, Hodge RH. Linking clinic patients to Internet-based, condition-specific information prescriptions. J Med Lib Assoc. 2010 Apr;98(2):160–4. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.98.2.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams MD, Wilder KS, Giuse NB, Sathe NA, Carrell DL. The Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS): an approach for a patient-centered service. Bull Med Lib Assoc. 2001 Apr;89(2):185–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall JG. The value of library and impact of library and information services [Internet] Keynote presented at: Canadian Health Library Association CHLA/ABSC 35th Annual Conference; Calgary, AB; 26–30 May 2011 [cited 14 May 2012]. < http://www.chla-absc.ca/2011/keynote_video>. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sathe NA, Jerome R, Giuse NB. Librarian-perceived barriers to the implementation of the informationist/information specialist in context role. J Med Lib Assoc. 2007 Jul;95(3):270–4. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.95.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julien H, Genuis SK. Emotional labour in librarians' instructional work. J Doc. 2009;65(6):926–37. doi: 10.1108/00220410910998924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]