Abstract

Background

In crosses between the proline-deficient mutant homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2 (p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2), used as male, and different Arabidopsis mutants, used as females, the p5cs2 mutant allele was rarely transmitted to the outcrossed progeny, suggesting that the fertility of the male gametophyte carrying mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 is severely compromised.

Results

To confirm the fertility defects of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants, transmission of mutant alleles through pollen was tested in two ways. First, the number of progeny inheriting a dominant sulfadiazine resistance marker linked to p5cs2 was determined. Second, the number of p5cs2/p5cs2 embryos was determined. A ratio of resistant to susceptible plantlets close to 50%, and the absence of aborted embryos were consistent with the hypothesis that the male gametophyte carrying both p5cs1 and p5cs2 alleles is rarely transmitted to the offspring. In addition, in reciprocal crosses with wild type, about 50% of the p5cs2 mutant alleles were transmitted to the sporophytic generation when p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 was used as a female, while less than 1% of the p5cs2 alleles could be transmitted to the outcrossed progeny when p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 was used as a male. Morphological and functional analysis of mutant pollen revealed a population of small, degenerated, and unviable pollen grains, indicating that the mutant homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2 is impaired in pollen development, and suggesting a role for proline in male gametophyte development. Consistent with these findings, we found that pollen from p5cs1 homozygous mutants, display defects similar to, but less pronounced than pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants. Finally, we show that pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants contains less proline than wild type and that exogenous proline supplied from the beginning of another development can partially complement both morphological and functional pollen defects.

Conclusions

Our data show that the development of the male gametophyte carrying mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 is severely compromised, and indicate that proline is required for pollen development and transmission.

Keywords: Proline, Male gametophyte, Arabidopsis, p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2

Background

In addition to its role as proteinogenic amino acid, and as a molecule involved in responses to a number of biotic and abiotic stresses, proline has been implicated in plant development, particularly flowering and reproduction [1-3]. The first convincing evidence that proline may play a key role in plant reproduction under normal unstressed conditions, came from measurements of free proline content in a number of plant species, which revealed low levels of proline in vegetative tissues followed, after flower transition, by proline accumulation in reproductive tissues and organs [4-8]. Chiang and Dandekar [7], for example, reported that free proline accumulates in Arabidopsis reproductive tissues up to 26% of the total amino acid pool, while in vegetative tissues represents only 1-3%. Among floral organs, different authors [7-11] pointed out that the floral organ with the highest proline content is pollen, where proline may represent more than 70% of the total amino acid content [8].

It is not clear, to date, the reason for such a massive proline accumulation in pollen. Because pollen grains undergo a process of natural dehydration, a role of compatible osmolyte capable of protecting cellular structures from denaturation, has been proposed by some authors [7,12,13], while others [14] have postulated a role for proline as a source of energy or as metabolic precursor to support the rapid and energy-demanding elongation of the pollen tube. On the other hand, the rapid elongation of the pollen tube requires extensive synthesis of cell wall proteins [15], some of which are rich in proline or hydroxyproline stretches, and proline accumulation may be needed to sustain the synthesis, at high levels, of proline-rich cell wall proteins [16].

Irrespective of its function, proline may accumulate in pollen due to an increased transport from external sources, or to an increased ratio between synthesis and degradation of endogenous proline, or because of a combination of the two, but no conclusive evidence has been produced, as yet, to distinguish among these alternative models. Long distance transport of proline through phloem vessels has been documented [17,18] and since AtProT1 (AT2G39890), a gene encoding an amino acid carrier recently shown to mediate proline uptake in plants, is highly expressed in mature pollen [19], transport has been proposed to account for proline accumulation in pollen grains. However single, double, and triple knockout mutants for all the genes belonging to the AtProT family are available, and none of them show difference, compared to wild type, neither in proline content, nor in pollen germination efficiency [19], raising the possibility that endogenous proline synthesis may be responsible for, or contribute to proline accumulation in pollen.

In higher plants proline synthesis proceeds from glutamate that is converted to proline in a two-step pathway catalyzed by the enzymes Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate ynthetase (P5CS), and Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (P5CR). The existence of an alternative route for proline synthesis, converting ornithine to proline by the action of δ-ornithine-amino-transferase (δ-OAT; At5g46180) and P5CR, has been hypothesized by some authors [20,21]. However the relevance of this pathway for proline synthesis has been recently questioned [22] and glutamate may be the only precursor of proline synthesis in plants. P5CS, regarded as the rate-limiting enzyme for proline biosynthesis in plants, is encoded in Arabidopsis by the two paralog genes P5CS1 (At2g39800) and P5CS2 (At3g55610) [23], while no paralog genes have been described for P5CR (At5g14800).

T-DNA insertional mutants have been characterized [1,3,24] for both P5CS1 (SALK_063517, p5cs1-4) and P5CS2 (GABI_452G01, p5cs2-1;FLAG_139H07, p5cs2-2), providing hints for assigning gene functions. P5CS1 is responsible for abiotic stress-induced proline accumulation, as homozygous p5cs1 mutants do not accumulate proline upon stress induction and are hypersensitive to environmental stresses [3,24], while P5CS2 is necessary for embryo development, as homozygous p5cs2 mutants are embryo lethal and the p5cs2 mutant allele can be propagated only in p5cs2/P5CS2 heterozygous mutants [1,24]. In addition, both genes have been shown to modulate flower transition in Arabidopsis, as the flowering time of mutants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2, is more delayed than that of the single p5cs1 mutant [1,2].

In the course of a genetic screen designed to identify the floral pathway(s) proline interacts with in Arabidopsis (Mattioli et al., in preparation), we found that the p5cs2 mutation was rarely transmitted to the offspring when the proline-deficient p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 was used as a pollen donor suggesting yet another role for proline in affecting male fertility. This prompted the analysis presented in this work, aimed to evaluate the role of endogenous proline in pollen development and fertility. We show here that the development of the male gametophyte carrying mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 is severely compromised, indicating a role for proline in pollen function and development.

Results

In crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2, used as male, and Arabidopsis flowering time mutants, used as females, aimed to understand the flowering pathway proline interacts with (Mattioli et al., in preparation), the p5cs1 mutant allele was always transmitted to the outcrossed progeny, while the transmission frequency of the p5cs2 mutant allele was exceedingly low (in average 0.8 ± 0.1%). Since no obvious gametophytic defects have been ever noticed neither on p5cs1 nor on p5cs2 single mutants, this result suggests that a male fertility defect may be linked to pollen grains bearing mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 genes.

Segregation of the p5cs2 mutant allele in a seed population from self-pollinated p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants is consistent with the presence of a gametophytic mutation

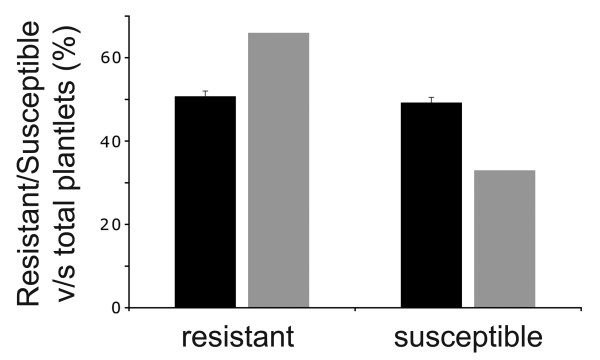

To verify the fertility defects of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants, the segregation of the sulfadiazine gene – a dominant resistance marker associated to the T-DNA insertion on P5CS2 – was analyzed in a seed population from selfed p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. Since the homozygous p5cs2 single mutant is embryo lethal [1], we expected that the segregation of the p5cs2-linked sulfadiazine resistance in the selfed population would approximate a 2:1 ratio of resistant over susceptible plants. If, on the other hand, the segregation ratio for the p5cs2 mutant allele should approximate a 1:1 ratio, a fertility defect for the gametophyte carrying both p5cs1 and p5cs2 mutations would be confirmed. To clarify this point, 831 seeds, from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, were planted on sulfadiazine plates in six independent experiments. As shown in Figure 1, the p5cs2 mutation segregated in a 1:1 resistant:susceptible ratio, as about 50% (50.6 ± 0.1%; n= of 831; p*** < 0.000 1; χ2 = 45) plantlets were sulfadiazine resistant (black bars in Figure 1), consistent with the hypothesis that the p5cs1 p5cs2 gametophyte is infertile and can hardly transmit the p5cs2 allele to the sporophytic generation.

Figure 1.

Segregation of the p5cs2 mutant allele in a self-pollinated p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 population. Percentage of resistant versus total plantlets (black left column) or susceptible versus total plantlets (black right column) grown under sulfadiazine selection are shown. The corresponding gray columns represent the percentages expected if the p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 were not a gametophytic mutant. Values represent the means of six independent experiments ± SE.

The absence of aborted embryos in p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 siliques is consistent with a gametophytic mutation hampering homozygous formation

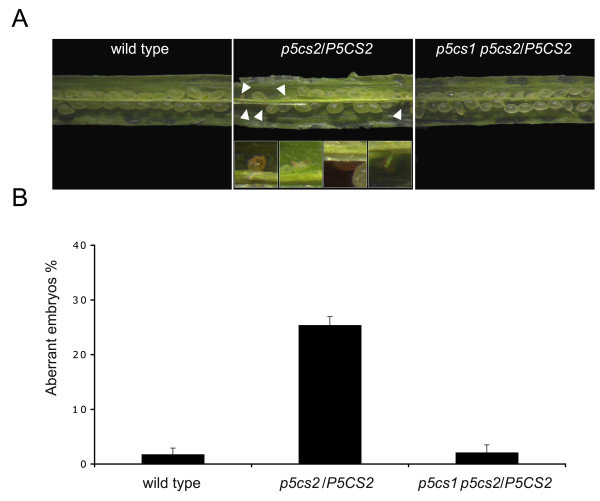

To further confirm the gametophytic defect of the p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutant, the incidence of embryo abortion was examined in the siliques of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2. Aborted seeds could be observed in the siliques of a self-pollinated heterozygous p5cs2/P5CS2 mutant, accounting for about 25% of the total seeds and corresponding to the genotype p5cs2/p5cs2 (Figure 2, middle, see white arrowheads) compared with about 1% of spontaneous seed abortion found in wild type siliques (Figure 2, left). However, in case a gametophytic defect should impede homozygous formation, the absence of aborted embryos in the siliques of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 would be expected. Indeed, as shown in the right part of Figure 2, p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 siliques show a wild type-like phenotype with less than 1% aborted seeds. These data are in agreement with the hypothesis that the (male) gametophyte carrying both p5cs1 and p5cs2 alleles is rarely transmitted to the offspring.

Figure 2.

Morphological analysis of seed defects in siliques of wild type, p5cs2/P5CS2 and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. The percentage of aberrant versus normal seeds was scored in wild type, p5cs2/P5CS2 heterozygous and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants. While siliques from heterozygous p5cs2 mutant (A and B, middle) present ~25% of aberrant seeds (white arrowheads) the percentage of seed abortion of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 siliques (A and B, right) is indistinguishable from wild type (A and B, left). Details, at higher magnification, of some of the aberrant seeds of figure B (middle) are shown in the insets. Values represent the means of four independent experiments ± SE.

Reciprocal crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type confirm the male gametophytic defects associated to pollen grains mutated in both P5CS1 and P5CS2

To confirm genetically the male sterility of pollen grains carrying both p5cs1 and p5cs2 mutant alleles, reciprocal backcrosses were made between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type plants. All seeds produced by the outcrossed siliques were collected and germinated on sulfadiazine-containing media, to follow the transmission of the p5cs2 mutant allele (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, when pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants was used to fertilize wild type pistils, the p5cs2 mutant allele could be transmitted to the progeny only in 1 out of 132 plants (0.76 ± 0.09%; χ2=128; P<0.001), producing a p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 genotype. In contrast, transmission of the p5cs2 allele in reciprocal crosses occurred in 41 out of 92 cases, suggesting that mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 have no effects on the female gametophyte.

Table 1.

Reciprocal crosses betweenp5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2mutants and wild type plants

| Crosses (Female×male) |

Genotype of the progeny |

|

|---|---|---|

| p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 | ||

|

wt×p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 |

1/132 (0.75%)*** |

131/132 (99.15 %)*** |

| p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2×wt | 41/92 (45%) | 51/92 (55%) |

Reciprocal crosses between mutants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2 and wild type plants. *** Significantly different from the expected segregation ratio of 50% (P < 0.001).

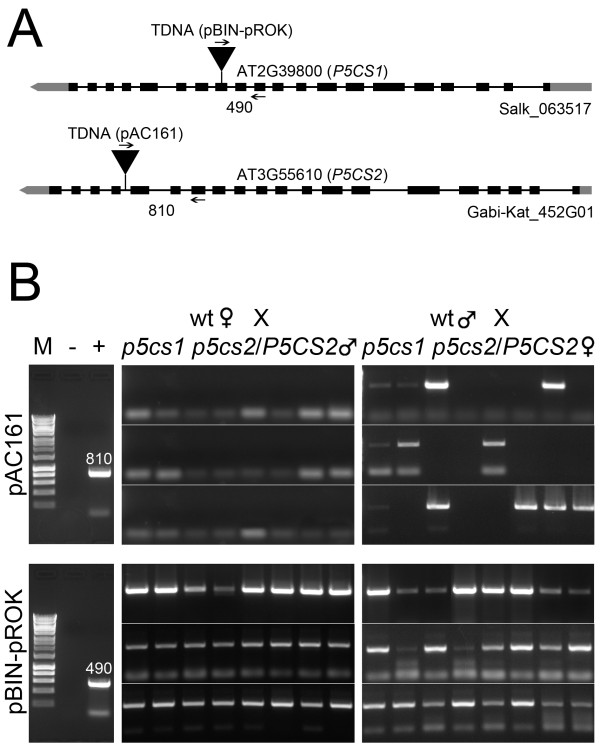

To confirm these data at molecular level, 24 individuals were randomly chosen from each outcrossed progeny (male p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 × female wt, and female p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 × male wt) and analyzed by PCR for the presence of the T-DNA insertion on P5CS2 (Figure 3A and 3B, top panel), and on P5CS1 (Figure 3A and 3B, bottom panel). As shown in the top panel of Figure 3B, when p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 was used as a male, a combination of primers specific for P5CS2 and for the T-DNA vector pAC161 could not detect the presence of a T-DNA insertion on P5CS2 (Figure 3B leftmost top panel). On the contrary, when p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 was used as a female, a PCR product specific for the T-DNA insertion on P5CS2 was amplified in 12 out of 24 samples (Figure 3B rightmost top panel), providing molecular support that the transmission of the p5cs2 mutant allele is compromised in male, but not in female gametophytes from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. In addition, as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 3B, all the samples analyzed detected both the presence of a mutant p5cs1 allele (Figure 3B left and right bottom panel), by using a couple of primers specific for P5CS1 and for the T-DNA vector pROCK, and the presence of a wild type P5CS1 allele (not shown), by using a primer pair specific for P5CS1, indicating that the chosen plants derived from an outcrossing event, and excluding the possibility of an unintended contamination from self-pollinated parental genotypes. Overall, the reciprocal crosses with wild type plants provide genetic and molecular evidence that p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 is impaired in male fertilization.

Figure 3.

Molecular analysis of reciprocal crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants and wild type. (A) Schematic drawing of the insertional mutant p5cs1(Salk_063517) and p5cs2 (Gabi-Kat _452G01). The position of the T-DNA insertion, the location of the PCR primers used for genotyping, and the expected length of the PCR products are shown for P5CS1 (At2G39800), and P5CS2 (At3G55610). (B) PCR amplification of T-DNA insertions associated to P5CS2 (PAC161 T-DNA, top panels) and P5CS1 (pROK T-DNA, bottom panels) in reciprocal crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type. Samples from 24 randomly chosen outcrossed plantlets are shown. The Results shown on top panels indicate that the P5CS2 mutation is never transmitted to the progeny (0/24) when p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 serves as a male (top panel left), but is normally segregated (12/24), when serves as a female. Negative and positive controls are shown in the leftmost panel, relative to the amplification of wt (− ,top and bottom leftmost panel), p5cs2/P5CS2 (+, top leftmost panel) and p5cs1 (+, bottom leftmost panel) parental genotypes. The numbers next to the PCR products represent the expected molecular weight expressed in Kb for the P5CS2-T-DNA (top panel), and P5CS1-T-DNA (bottom panel) junction fragments, respectively.

Morphological and functional analysis of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants reveals severe defects in pollen development

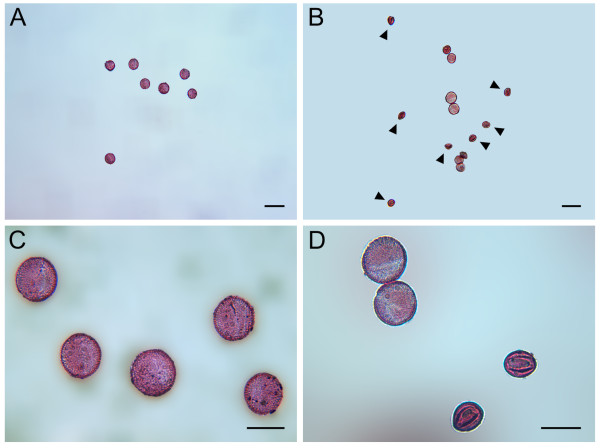

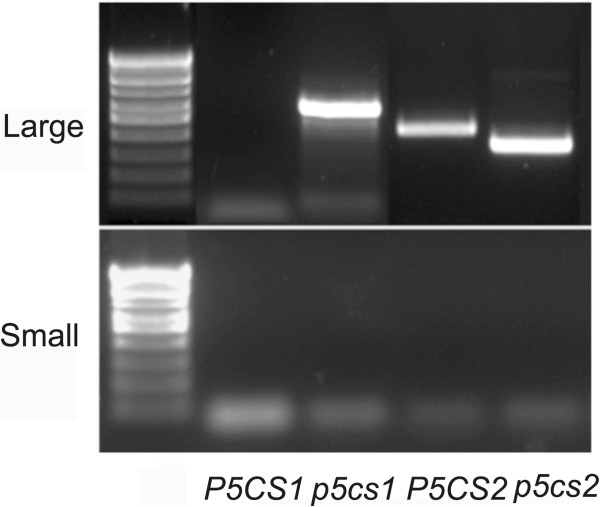

If p5cs1 p5cs2 pollen is impaired in male fertilization, morphologic abnormalities in pollen grains may be expected. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, microscopic analysis of mature pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, stained with acetic orcein, revealed (Figure 4B and D), alongside normal-looking grains, a population of small, misshaped and shriveled pollen grains, roughly accounting for half of the total pollen population (46.23 ± 1.2%). This evidence indicates that in plants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2, the development of the male gametophyte is impaired and suggests that this defect may arise in pollen of p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype. To understand at which stage of pollen development the aberrations took place, toluidine-stained histological cross-sections of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anthers, from different developmental stages [25], were prepared and analyzed in comparison to wild type. As shown in Figure 5, the first clear differences between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type anthers appear from stage 11 (Figure 5F and N), when two populations of pollen grains – one similar to wild type, and another showing smaller size and initial signs of degeneration - can be distinguished in the pollen sacs. In order to assess whether this small abnormal pollen is vital, pollen grains from wild type and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants were treated with Alexander’s stain, a staining procedure capable of distinguishing viable, red-colored pollen from non viable, green or unstained pollen [26,27]. As shown in Figure 6, a population of small and abnormal pollen grains, representing 47.5 ± 2.1% of the total pollen grains, appear selectively unstained when treated with Alexander’s stain (Figure 6B and D, and Additional file 1: Figure S1). In contrast, the larger and normal-looking pollen present in the pollen population from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, takes up Alexander’s stain and appear as red as wild type pollen (Figure 6A and C, and Additional file 1: Figure S1). In addition, within the pollen population from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants, while the large pollen grains seem to have a normal nuclear content, the small and unviable pollen grains appear degenerated and devoid of DNA as judged by DAPI (Figure 7A and B) and PCR analysis (Figure 8). Indeed, in DAPI-stained pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2, no nuclei were ever observed in the small and abortive pollen grains, while up to three nuclei can be seen in the large and normal-looking pollen grains, as in normal pollen (Figure 9F).

Figure 4.

Morphological analysis of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type. Acetic orcein stain of pollen from wild type (A and C) and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants (B and D) at two different magnifications show the presence in the latter pollen of small and shriveled pollen grains (arrows) alongside normal-looking grains. Bars = 50 μm (A, B) and 25 μm (C,D).

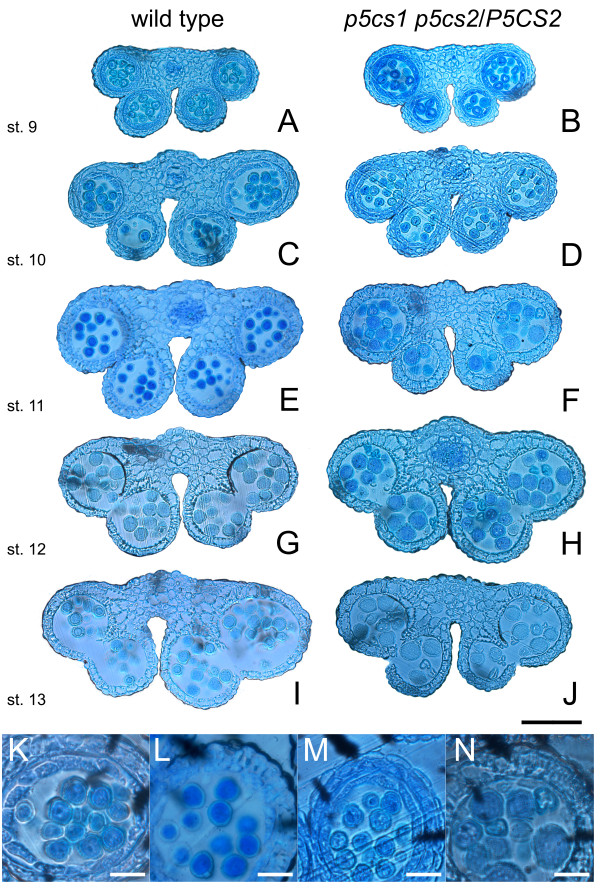

Figure 5.

Histological analysis of wild type and mutant pollen. Cross-sections of anthers of different developmental stages. Toluidine blue-stained cross-sections of anthers from wild type (A,C,E,G,I) and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 (B,D,F,H,J) from stage 9 to 13 are shown. The first clear differences between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type anthers appear from stage 11 (E,F), when two populations of pollen grains can be distinguished in the pollen sacs. Bar = 100 μm. (K-N) Details at higher magnification of anthers from wild type (K,L) and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 (M,N), relative to stage 10 (K,M) and 11 (L,N), respectively. Small misshaped pollen grains are clearly visible from stage 11 (E). No significant alterations, compared to wild type, are seen in anthers from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 before stage 11. Bar = 25 μm.

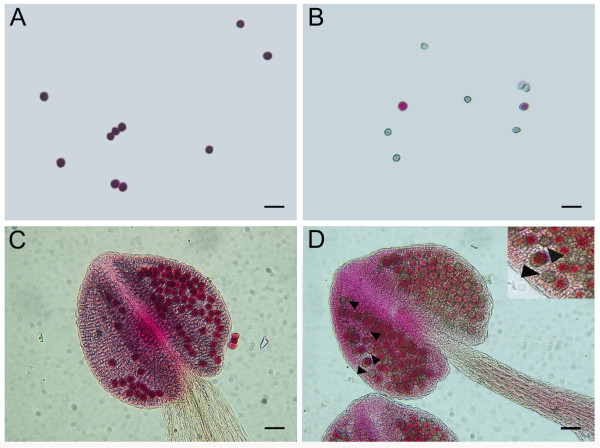

Figure 6.

Alexander's stain of pollen from wild type and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. Alexander's staining of pollen and anthers from wild type (A,C) compared to p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutant (B,D) reveals that a fraction of the mutant pollen population, looking small and misshaped, is not viable, as does not assume Alexander's stain. In contrast the remaining fraction of the pollen population appears as red as, and indistinguishable from wild type pollen. A detail of pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutant is shown in the inset at higher magnification. Bars = 50 μm.

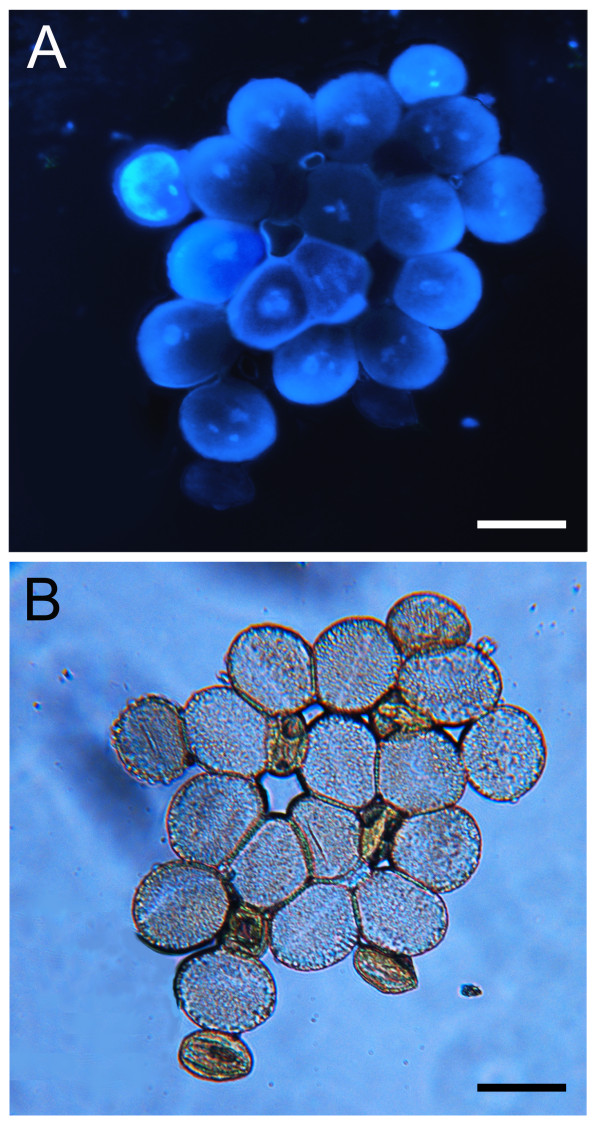

Figure 7.

DAPI analysis of pollen from wild type and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2. (A) DAPI staining of mature pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2. The small misshaped pollen of the mutant pollen population appears highly degenerated and depleted of nucleus. In contrast the larger and wild-type looking pollen grains display up to three nuclei, as in normal wild type pollen. (B) Bright-field image of the same picture showing large and small mutant pollen grains. Bar = 25 μm.

Figure 8.

PCR analysis of large and small pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. DNA extracted from pools of large and small pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants was genotyped by PCR for the presence or absence of insertional mutations in P5CS1 and P5CS2. No DNA could be amplified from the small pollen population (bottom panel), while both p5cs1 and p5cs2 mutant alleles, as well as the wild type P5CS2 allele, were amplified from large pollens (top panel).

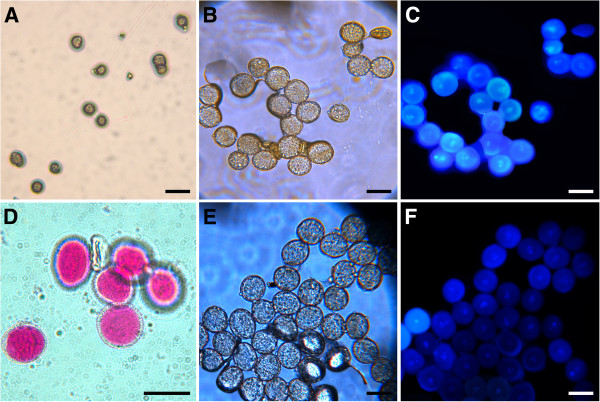

Figure 9.

Morphological analysis of pollen from p5cs1 homozygous mutants. In support of a proline requirement for pollen development, morphologic analysis of pollen from p5cs1 homozygous mutants revealed the presence of degenerated pollen grains (A-D), unstained with Alexander's stain (D) and lacking visible nuclei with DAPI staining (C, and bright-field control in B). Up to three nuclei are visible in pollen from wild type control (F, and bright-field control in E). Bars= 50 μm (A), 25 μm (B-D).

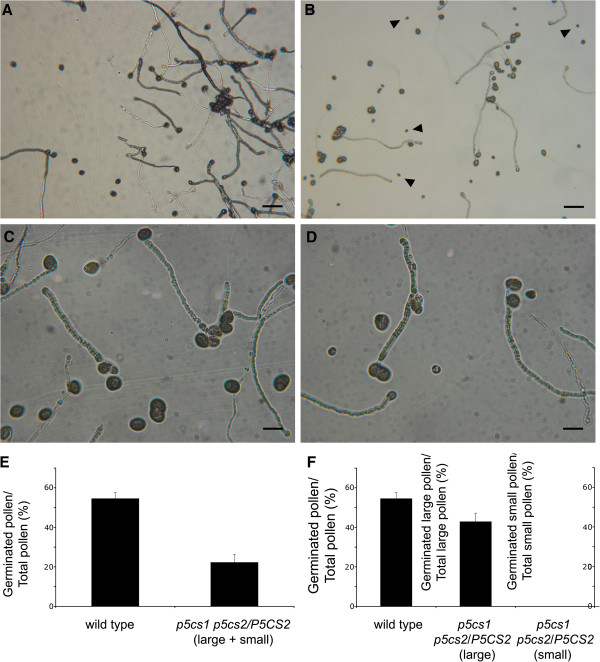

In vitro germination assays confirm that p5cs1 p5cs2 pollen is essentially non viable, and suggest a quantitative role for proline in pollen development

To further investigate the pollen viability of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, an in vitro germination assay was performed to test the capability of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants to germinate in vitro (Figure 10B, D), as compared as to wild type pollen (Figure 10A, C). As reported in Figure 10, when pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants was grown on solid germination medium, the percentage of germinated versus total pollen (germinated + non germinated), including both large and small pollen grains, was reduced by ~ 50% (22 ± 4% compared to 54 ± 2.9% of control) compared to wild type (Figure 10, panel E). The fact that the germination percentage of wild type pollen was, on average, only 54 ± 2.9% can be accounted for by the relative inefficiency of this kind of experiments. It is known that in vitro germination cannot fully substitute for in vivo germination, with germination percentages showing ample variations [28]. In order to minimize this inherent variability, all experiments were carried out by placing, on the same microscope slides, pollen from wild type controls close to pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants. Since genetic analysis indicated that half of the pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants are of p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype, and morphological observations showed that ~ 50% of the pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants are small and misshaped, it is likely to hypothesize that all the aberrant pollens are p5cs1 p5cs2. According to this notion when large and small pollen grains are scored separately, all the small and degenerate pollen grains (p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype) should fail to germinate, while all the large and wild type-looking pollens (p5cs1 P5CS2 genotype) should elongate a pollen tube. To verify this point, the percentage of pollen germination was calculated separately for large and small pollen grains, either as number of large germinated pollen grains out of total large pollen grains, or as small germinated pollen grains out of total small pollen grains (Figure 10, panel F). Unexpectedly, while small pollen grains were never observed to germinate (Figure 10, panel B and D), the germination percentage of the large pollen grains vs. total large pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants was not 100%, but accounted for only 89% of that of wild type (43 ± 4.2% compared to 54 ± 2.9% of control pollen), as shown in Figure 10F, middle column, suggesting that the two pollen populations may not be pure, i.e. some pollen of p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype might occasionally have degenerated and looking small, while some pollen of p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype may be not, or not completely, degenerated and yet looking large. To clarify this point, pools of either large or small pollen grains were analyzed by PCR for the presence or absence of T-DNA insertions in P5CS1 and P5CS2. As shown in Figure 8, no DNA could be amplified from the small pollen population, as expected from their morphological and functional degeneration and apparent absence of intact nuclei. When DNA from the large pollen population was examined for the presence of mutations in P5CS1, only the T-DNA insertion on P5CS1 could be amplified (Figure 8), confirming that the large pollen grains are vital and indicating that the whole population contains the mutated p5cs1 allele, as expected from a line homozygous for the p5cs1 allele. However, when DNA from the large pollen population was examined for the presence of mutations in P5CS2, both wild type and mutant P5CS2 allele were found, as witnessed by the presence of specific PCR products for both wild type and mutant P5CS2 gene (see the two rightmost lines of Figure 8), confirming that the wild-type like pollen contains, to some extent, pollens carrying mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2. The presence of pollens containing mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 within the large, wild-type looking pollen population, suggests that pollen with genotype p5cs1 P5CS2 is likely present within the degenerated pollen population. The simplest interpretation of these results is that proper development of the male gametophyte is dependent from proline availability, and that pollens of genotype p5cs1 p5cs2 may contribute to some extent to the overall fertility defect of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants. An important implication of this reasoning is that pollen defects similar to, but less severe than those found on pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants should be present in pollen grains from homozygous p5cs1 single mutants. Accordingly, mature pollen was collected from a homozygous p5cs1 single mutant, and analyzed for pollen morphology and vitality by microscopic analysis, Alexander's stain, DAPI stain, and in vitro germination assay. As shown in Figure 9, microscopic and functional analysis of p5cs1 pollen grains revealed the presence of misshaped (Figure 9A-D), non-viable (Figure 9D) and degenerated (Figure 9B and C) pollen grains, although to a lesser extent (~ 18%) compared to pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants. Moreover, as shown in Additional file 2: Figure S2, pollens from p5cs1 single mutants grown on germination medium, exhibited a ~ 12% reduction of germination rate, compared to wild type pollens. As seen in Additional file 2: Figure S2, A the percentage of germinated versus total pollen, including both large and small pollen grains, is 40 ± 2,0%, compared to 54 ± 2,9% of wild type control, confirming that male gametophytic defects are present, to a lesser extent, in p5cs1 single mutants too. In addition, when large and small pollen grains are scored separately (Additional file 2: Figure S2, B), the percentage of large versus total large germinated pollen is 48 ± 2,5%, compared to 54 ± 2,9% of wild type control, while small pollen grains were never seen to germinate. As in p5cs1 single mutant the percentage of large germinated pollen grains is not significantly different from that of wild type pollen grains, the 12% reduction of germination efficiency must be accounted for by the small and degenerated pollen fraction.

Figure 10.

In vitro germination assays of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. To assess the viability of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, pollen from wild type (A and, at higher magnification, C) and p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 (B and, at higher magnification, D) was incubated in vitro on germination medium and scored for successful germination (pollen tube fully or partially elongated). In panel (E) the percentage of germinated versus total pollen is shown for wild type (left column) and mutant pollen (right column). In (F) the percentage of germination over total pollen is given for either large (middle column) or small (rightmost column) mutant pollen, compared to wild type (leftmost column). Bars = 100 μm (A, B) and 25 μm (C,D). Values in (E) and (F) represent the means of four independent experiments ± SE.

Proline content analysis and exogenous proline treatment of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants provides a direct correlation between proline and pollen development

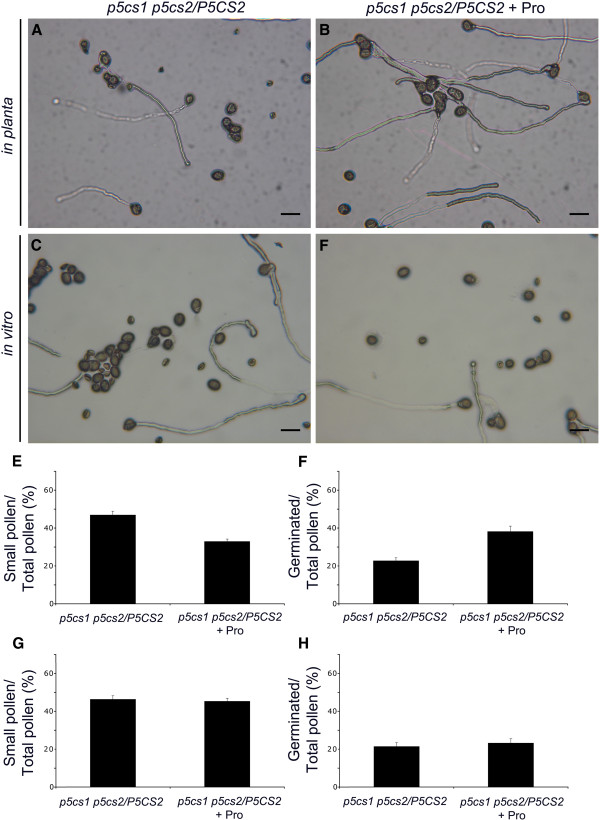

On the whole, the data presented above point to a requirement for p5CS1 and p5CS2 in pollen development and functionality. To establish a direct correlation between proline and pollen development, we measured the proline content of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, compared to wild type. About 7.000 mature pollen grains from either wild type or p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants were collected on a microscope slide and processed with a modification (see methods for details) of the Bates method [29]. The measurements were repeated in three independent experiments and expressed as average values ± SE. A clear difference in proline content was detected between the two pollen populations, as 336 ± 31 ng of free proline, roughly corresponding to 48 pg/pollen, was detected in wild type pollen, while only 105 ± 23 ng of free proline, corresponding to 15 pg/pollen of proline, could be detected in the mixed pollen population (large and small pollen grains) from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. The low content of proline measured in pollen from mutant plants (15 pg/pollen), compared to that found in wild type pollen (48 pg/pollen), provides a direct correlation between proline deficiency and pollen defects. Because in a pollen population from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, approx 50% of the pollen grains look aberrant, a ~ 50% reduction of proline content is expected. However, a proline reduction exceeding 70% was detected in pollen from mutant plants. This result suggests that the observed proline reduction cannot be accounted for only by the abortion of the small misshaped pollen, but that a reduction in proline content must take place, to some extent, also in the large wild type-looking pollen grains. In addition, 10 μM L-proline was supplemented in vitro to mature pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants grown on germination medium, or in planta to developing anthers. As shown in Figure 11, while no significant effect on pollen germination was produced by proline supplemented in vitro (Figure 11C, D, G and H), a significant complementation of pollen defect was observed when proline was sprayed daily to inflorescence buds, from early developmental stages to fully developed dehiscent anthers: the percentage of aberrant pollens decreased from 47.0 ± 2.5% to 33.0 ± 1.5% (Figure 11E), and the percentage of germinated pollens increased from 21.3 ± 1.3% to 39.2 ± 2.1% (Figure 11F). This indicates that exogenous proline can partially rescue the defects of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants, when supplemented from the beginning of pollen development, confirming that proline plays a role in pollen development.

Figure 11.

Exogenous proline treatment of anthers and pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants. To confirm a proline requirement for pollen development and functionality 10 μM proline was supplied either in vitro to germinating pollens (C,D,G,H) or in planta to developing anthers (A,B,E,F). While in vitro proline treatment of pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants produces no differences in germination percentage (E, F), in planta supplementation gives rise to a significant improvement of germination efficiency (G, H). Bars = 50 μm. Values in (E to F) represent the means of four independent experiments ± SE.

Discussion

On the basis of crosses showing that pollen with genetic defects in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 is almost completely unable of a successful fertilization, a requirement for proline in male gametophyte viability was hypothesized and demonstrated here, by means of genetic, developmental and molecular evidence.

Proline is required for pollen development and fertility

Massive accumulation of proline has been reported in anthers and pollen by different authors in a number of species [7-11,14], but it is not yet clear why such high amount of proline is required. Functions as diverse as free radical scavenger [12], protector of membranes and cellular structures [13], energy source [15], metabolic precursor [14], and main amino acid constituent of hydroxyproline-rich cell walls [16] have been proposed but none of these possibilities has attained wide acceptance, and the interesting hypothesis that multiple functions may be accounted for by proline action has been suggested [30].

Evidence provided in this work indicates that pollen from mutants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2 can transmit the p5cs2 mutation with an overall frequency of about 0.8%, and that mutants with decreasing levels in proline content [2,3,24] have increasing problems in pollen viability indicating that proline is required for male fertility.

Proline accumulation in pollen may rely on endogenous proline synthesis

Apart from the defects in pollen development described in this work, and from a delay in flower transition described by Mattioli et al. [1], the vegetative and reproductive growth of mutants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2, including the development of the female gametophyte, is essentially normal. This evidence implies that the small amount of proline coming from the activity of the wild type P5CS2 allele, always present in the sporophytic tissues of p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2, is sufficient for normal growth and reproduction, but not for proper pollen development.

The specific requirement of proline for pollen development and function, is confirmed by the high amount of proline found in pollen by different authors [7-11,14], by the very low level of proline measured in mutant pollen, and by the partial rescue of pollen defects obtained by exogenous proline treatment. While this complementation provides direct proof that proline is required for pollen development and function, it gives no indication whether the required proline derives uniquely from endogenous synthesis inside the pollen or also from proline synthesized in nearby mother cells and transported or diffused inside pollen grains. This point clearly needs to be understood in future works.

However, since pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 is infertile, a possible transport or diffusion of proline synthesized in surrounding sporophytic cells by the residual P5CS2 allele is obviously insufficient. Furthermore, single, double and triple knockout mutants of the AtProT genes (At2G39890, At3G55740, At2G36590) responsible for proline transport in plants, have been isolated and characterized but none of them revealed alterations, compared to wild type, neither in proline content nor in pollen germination efficiency [19]. Although the possibility that different carriers, such as AtLHT5 (At1g67640) [31] or AtLHT7 (At4G35180) [32], may compensate, overlap to, or substitute for AtProTs, current evidence does not support a role of transport for proline accumulation in pollen grains. In addition, microarray data indicate that all the genes involved in proline synthesis are strongly expressed in pollen [33,34], and data from Szekely et al. [24], who detected in the pollen of Arabidopsis the expression of both AtP5CS1–GFP and AtP5CS2–GFP, confirm the presence of the P5CS protein in the male gametophyte. Overall these data suggest that proline is actively synthesized in pollen.

The question whether proline may be synthesized directly in pollen grains has been the object of controversial discussions, because some authors could detect low [8,32] or no expression of P5CS in pollen [19], while others reported the presence of an AtP5CS-GFP protein in the pollen of Arabidopsis, suggesting that biosynthesis of proline takes place in this organ [24]. However, the discrepancy in the expression levels of P5CS gene as observed by different authors [8,19,24,32], may depend on the developmental stage in which pollen was analyzed, and we may speculate that P5CS1/2 genes could be expressed only in particular stages of pollen development, and still accumulate enough P5CS enzyme to satisfy overall proline demand for pollen maturation. Temporal discrepancies between transcript and protein levels have been reported in pollen also for other genes, such as AtSUC1 (AT1G71880), whose transcript level is high at tricellular stage and low in mature pollen [35] and AtSTP9 (AT1G50310), whose gene product can only be detected by immunofluorescence microscopy after the onset of germination [36]. In addition, as above stated, high levels of expression of either P5CS1, P5CS2, and P5CR are detected in pollen by microarray analysis [33,34], directly confirming that endogenous proline synthesis from glutamate takes place in pollen grains. Unexpectedly, microarrays analysis also detects the expression of δ-OAT in pollen, although ornithine pathway seems not able to compensate P5CS deficiency in pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2. These contrasting pieces of evidence can be reconciled if ornithine pathway does not contribute to proline synthesis. Incidentally, this evidence supports the finding of Funck et al. [22] who demonstrated that the ornithine pathway is essential for arginine catabolism but not for proline synthesis.

Overall, proline accumulation in pollen may rely essentially on endogenous proline synthesis, although is yet to be understood whether proline derives uniquely from endogenous synthesis inside the male gametophyte or also from proline synthesized in nearby sporophytic cells and transported or diffused inside pollen grains. A likely hypothesis is that, as pollen lose desmosomal connections to surrounding sporophytic cells, becomes dependent on endogenous proline synthesis, consistent with the late appearance (stage 11) of visible aberrations in developing pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2, and with the absence of obvious defects in female gametopytes, always embedded in sporophytic cells.

Relationship between p5cs and p5cr mutants

Intriguingly, two Arabidopsis mutants bearing T-DNA insertions on P5CR, emb-2772-1 and emb-2772-2[37] exhibit an embryo lethal phenotype, similarly to p5cs2 mutants, halting embryo development at a preglobular stage. In sharp contrast, however, no gametopytic defects have been associated, so far, to these mutants.

While it is not surprising that lesions in P5CR and P5CS2, two genes coding for proline synthesis enzymes belonging to the same pathway, may lead to similar defects in embryo development, it is puzzling that, contrary to p5cs2, emb-2772 exhibits no gametophytic defects. In Arabidopsis a number of mutants have been described by Muralla et al. [38] with defects in embryo but not in gametophyte development.

To explain this apparent paradox, the authors propose that gene products derived from transcription of wild type alleles in heterozygous sporocytes may compensate the deficiency of the mutant gametophytes, and that embryo lethality results when these products are eventually depleted. Likewise, we may speculate that, contrary to P5CS2, the P5CR transcript and/or protein, synthesized in heterozygous sporocytes, is stable enough to sustain pollen but not embryo development.

Proline may have distinct roles in pollen development and germination

The data presented here suggest that proline is required for pollen development, but gives no indication on the role of proline in pollen development. We know from histological analysis (Figure 5) that a fraction of pollen grains begins to look shriveled and shrunk from stage 11, when, after completion of the two mitotic divisions, the microspores start their maturation to pollen grains. As pollen development proceeds, it becomes more and more desiccated, and increasing amounts of proline may be needed to avoid protein denaturation and preserve cellular structures, including nuclei, as hypothesized by Chiang and Dandekar [7]. A role for proline in the protection of cellular structures from denaturation has been proposed by different authors either as compatible osmolyte [7], scavenger of free radicals [12,24], or as protector of membranes and cellular structures [13]. Although, from available data, a defect in mitotic divisions cannot be ruled out, the degeneration of the cellular structures observed in pollen grains of p5cs1 p5cs2 genotype, may be caused by the irreversible damages on cellular membranes caused by the process of dehydration in absence of the protective action of proline.

Once pollen has reached full maturation, accumulated proline is catabolized and serves as source of energy - to fuel the rapid and energy-demanding elongation of the pollen tube [15,39] - and/or as metabolic precursor of γ-amino butyric acid (GABA), the catabolism of which has been shown essential for late pollen tube elongation and guidance [40].

In the future it will be interesting to address this issue by uncoupling these two putative functions, for example targeting in developing pollen grains from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants non-metabolizable compatible osmolyte, such as glycine betaine. Equally interesting it will be to dissect the role of proline synthesized in the haploid male gametophyte from that synthesized in diploid sporophytic tissues of the anther.

Conclusions

We show here that in mutants homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2, defective in proline synthesis, the development of the male gametophyte with mutations in both P5CS1 and P5CS2 is severely compromised, and provide genetic evidence that proline is needed for pollen development and fertility.

Methods

Plant growth conditions, segregation and embryo analyses

Wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis thaliana from Columbia-0 (Col-0) ecotype used in this work were grown in a growth chamber at 24/21°C with light intensity of 300-μE·m-2·s-1 under 16 h light and 8 h dark per day. Arabidopsis homozygous for p5cs1 (SALK_063517), originally obtained from the SALK collection, are knockout insertional mutants described in [3] containing a pROCK-derived T-DNA within exon 14. Arabidopsis heterozygous for p5cs2 (GABI_452G01), originally obtained from the GABI-Kat collection, are insertional mutants described in [1], containing a PAC161- derived T-DNA within exon 18. As reported in [1,3]p5cs2/P5CS2 is embryo lethal in homozygous state and must be propagated in heterozygous state. Arabidopsis homozygous for p5cs1 and heterozygous for p5cs2 (p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2), have been characterized and described elsewhere [1,3]. For segregation analysis, seeds from a self-fertilized p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plant were stratified for three days at 4°C, surface-sterilized, and germinated on MS1/2 plates supplemented with 12 μg/ml sulfadiazine. Segregation ratios were calculated by scoring the number of resistant over susceptible plantlets, and confirmed by PCR analysis of random samples. using primers 5’-CAAGCAATGGTGGAAGAGTAAA-3’ and 5’- CGGGGCTCAAGAAAAATCC -3’ for the sulfadiazine resistance gene. For embryo analysis, siliques derived from self-fertilized wild types, p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants, or p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 mutants, were dissected and analyzed under a Zeiss Stevi SV 6 light stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH, Jena, Germany). Digital images were acquired with a Jenoptik ProgRes® C3 digital camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany). All the analyses have been repeated at least four times. Statistical significance was inferred from percentage data by using χ2 analysis.

Plant crosses

In crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and flowering time mutants the F1 generation was allowed to self-fertilize and the presence of the p5cs2 mutant allele was assessed from the F2 generation, by sulfadiazine selection or by PCR genotyping of the sulfadiazine resistance gene. To confirm the data and rule out any possible interference of the flowering time mutant genotypes in the transmission of the p5cs2 mutation, reciprocal crosses between p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 and wild type were performed. Transmission of the T-DNA insertion on P5CS2 gene was assessed, either by sulfadiazine selection of outcrossed seeds germinated on sulfadiazine-containing solid medium, or by PCR genotyping of sulfadiazine resistance gene on plantlets grown without selection Statistical significance was inferred from percentage data by using χ2 analysis.

Morphological and functional pollen characterization

For orcein staining, pollen was collected by dabbing mature flowers, from four weeks old plants, on a microscope slide. After a brief incubation in 1% acetic orcein, the pollen grains were rinsed in 50% acetic acid and examined under a Leitz Laborlux D light microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Jenoptik ProgRes® C3 digital camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany). For histological analysis, floral buds, of different developmental stages, were embedded in Technovit 7100 (Kulzer), and 3-mm cross-sections were stained with 1% Toluidine blue as described in [41] and analyzed under a Leitz Laborlux D light microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany). For evaluation of pollen vitality, flower buds or isolated anthers were collected, fixed overnight in Carnoy’s fixative (6 alcohol:3 chloroform:1 acetic acid), and stained with a modified Alexander’s stain as described by Peterson et al. (2010). For DAPI (4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining [42], mature pollen was collected, incubated 30’ in DAPI staining solution (0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 0.4 μg/ml DAPI) and analyzed with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH, Jena, Germany) equipped with a DAPI filter set consisting of an excitation filter (BP 365/12 nm), a beam splitter (395 nm), and an emission filter (LP 397 nm). Acquisition of digital images was made with a Jenoptik ProgRes® C3 digital camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany).

Molecular analysis

Pollen grains were separated by size (large and small) under a Zeiss Stevi SV 6 light stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH, Jena, Germany) and pools of about 500 pollen grains were prepared and frozen at −20°C. Pollen DNA was extracted from these samples with a modified CTAB (cetyl trimethylammonium bromide) protocol according to [43]. Because of the presence of a tough pollen coat, major modifications were introduced in the initial steps consisting in squashing pollens between a microscope slide and a cover slip, retrieving them with 50 μl CTAB buffer and heating the solution for 15’ at 95°C. PCR conditions were 3’ at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 30” at 94°C, 1’ at 58°C, and 50” at 72°C. The primer pairs used were 5’-CAAGCAATGGTGGAAGAGTAAA-3’ and 5’-CGGGGCTCAAGAAAAATCC-3’ for the sulfadiazine resistance gene, 5’-GGAGCAGAATGGTTTTCTCG-3’ and 5’-TATCTGGGAATGGCGAAATC-3’ for the T-DNA insertion on P5CS2, 5’-GGAGCAGAATGGTTTTCTCG-3’ and 5’-TGGAAAACAGCAGCACTGTC - 3’ for the gene P5CS2, 5’-CTGTTGGGGGTAAACTCATTG-3’ and 5 -GCGTGGACCGCTTGCTGCAACT-3’ for the T-DNA insertion on P5CS1, 5’-CTGTTGGGGGTAAACTCATTG-3’ and 5’-CTCTGCAACTTCGTGATCCTC-3’ for the gene P5CS1.

In vitro pollen germination

Mature pollens from stage 13 flowers [44] were collected, transferred to glass slides coated with freshly prepared germination medium (5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 mM KCl, 0.01 mM H3BO3, 10% sucrose and 1.5% agarose, pH 8.0), and kept overnight in a moist chamber at 21°C. To minimize in vitro germination variability, pollen from wild type plants was always included nearby pollen from p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 plants on the same microscope slide.

For pollen germination analysis, the slides were examined under a Leitz Laborlux D microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) and digital pictures of randomly chosen fields were acquired with a Jenoptik ProgRes® C3 digital camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany). To determine pollen germination efficiency, the number of germinated and non-germinated pollens was scored from five, randomly chosen, fields per replica in four independent experiments. Statistical significance was inferred from percentage data by using χ2 analysis.

Proline determination and exogenous proline complementation

Proline measurements were modified from [29] as follows: Mature pollen grains (~ 5–10.000) were collected on a microscope slide, smashed with a slide cover glass, and retrieved with 30 μl of a 3% (w/v) aqueous solution of sulfosalicylic acid. After centrifugation (12.000 ×g for 10’), the supernatant was added to 30 μl of acid-ninydrin and 30 μl of glacial acetic acid and let react for 2 hours at 80°C in a micro-test tube made up by the tip of pasteur pipette heat-sealed at the two ends. The reaction mixture was extracted with 60 μl of toluene and its optical density measured at 520 nm with a NanoDrop 2000 micro-spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA). Proline concentration was determined from a standard curve built with L-proline. In vitro complementation was attempted by spotting mature pollens in microscope slides coated with germination medium supplemented with 10 μM L-proline. In vivo complementation was performed by daily spraying early developing inflorescences with 10 μM proline. Mature pollens from stage 13 proline-treated flowers were collected and analyzed as described above.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MT wrote and supervised the work, performed reciprocal crosses, orcein stains and Alexander’s stains, RM carried out segregation and silique analyses, DAPI stains, germination assays and proline complementation assays, CL carried out histological analyses, MB performed molecular analyses, PC gave financial support and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther stained with Alexander’s stain. Close up of a p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther stained with Alexander’s stain. The small and misshaped pollen grains are clearly visible, within a p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther, as non-stained pollen pollen grains alongside wild type-like, red stained, pollen grains. Bar = 50 μm.

Figure S2. In vitro germination assays of pollen from p5cs1 single mutants. To evaluate possible defects in pollen viability of a mutant bearing a single mutation in P5CS1 gene, pollen from a homozygous knockout p5cs1 mutant was incubated in vitro on germination medium and scored for germination. (A) Percentage of germinated versus total pollens (germinated + non germinated), including both large and small pollen grains (right column), compared to wild type (left column). (B) Percentage of large (middle column), small (right column), and wild type pollen (left column) versus large (middle column), small (right column) and wild type (left column) total germinated pollen. Values in (A) and (B) represent the means of four independent experiments ± SE.

Contributor Information

Roberto Mattioli, Email: roberto.mattioli@uniroma1.it.

Marco Biancucci, Email: marco.biancucci83@gmail.com.

Chiara Lonoce, Email: chiaralonoce@hotmail.it.

Paolo Costantino, Email: paolo.costantino@uniroma1.it.

Maurizio Trovato, Email: maurizio.trovato@uniroma1.it.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by research grants from MIUR, FIRB, and ERA-PG to PC and by a research grant from Università La Sapienza (Progetto di Ateneo) to MT.

References

- Mattioli R, Falasca G, Sabatini S, Costantino P, Altamura MM, Trovato M. The proline biosynthetic genes P5CS1 and P5CS2 play overlapping roles in Arabidopsis flower transition but not in embryo development. Physiol Plantarum. 2009;137:72–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli R, Costantino P, Trovato M. Proline accumulation in plants:not only stress. Plant signal Behavior. 2009;4:1016–1018. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.11.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli R, Marchese D, D’Angeli S, Altamura MM, Costantino P, Trovato M. Modulation of intracellular proline levels affects flowering time and inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansuyt G, Vallee J-C, Prevost J. La pyrroline-5-carboxylate réductase et la proline déhydrogénase chez Nicotiana tabacum var. Xanthi n.c. en fonction de son développement. Physiol Veg. 1979;19:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Venekamp JH, Koot JTM. The sources of free proline and asparagine in field bean plants, Vicia faba L., during and after a short period of water withholding. J Plant Physiol. 1988;32:102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mutters RG, Ferreira LGR, Hall AE. Proline content of the anthers and pollen of heat-tolerant and heat-sensitive cowpea subjected to different temperatures. Crop Sci. 1989;29:1497–1500. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1989.0011183X002900060036x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HH, Dandekar AM. Regulation of proline accumulation in Arabidopsis during development and in response to dessication. Plant Cell Environ. 1995;18:1280–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00187.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R, Grallath S, Breitkreuz KE, Stransky H, Frommer WB, Rentsch D. LeProT1, a transporter for proline, glycine betaine, and -amino butyric acid in tomato pollen. Plant Cell. 1999;11:377–391. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo U, Stinson HT. Free amino acid differences between cytoplasmic male sterile and normal fertile anthers. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1957;43:603–607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.7.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogaard H, Andersen AS. Free amino acids of Nicotiana alata anthers during development in vivo. Physiol Plant. 1983;57:527–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1983.tb02780.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lansac AR, Sullivan CY, Johnson BE. Accumulation of free proline in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) pollen. Can J Bot. 1996;74:40–45. doi: 10.1139/b96-006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N, Cumbes QJ. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:1057–1060. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(89)80182-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour M. Protection of plasma membrane of onion epidermal cells by glycine betaine and proline against NaCl stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1998;36:767–772. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(98)80028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-qu Z, Croes AF. Proline metabolism in pollen: degradation of proline during germination and early tube growth. Planta. 1983;159:46–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00998813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-qu Z, Croes AF, Linskens H. Protein synthesis in germinating pollen of Petunia: Role of proline. Planta. 1982;154:199–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00387864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowalter AM. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell. 1993;5:9–23. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girousse C, Bournoville R, Bonnemain JL. Water deficit-induced changes in concentrations in proline and some other amino acids in the phloem sap of alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:109–113. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä P, Peltonen-Sainio P, Jokinen K, Pehu E, Setälä H, Hinkkanen R, Somersalo S. Uptake and translocation of foliar-applied glycinebetaine in crop plants. Plant Sci. 1996;121:221–230. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(96)04527-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann S, Gumy C, Blatter E, Boeffel S, Fricke W, Rentsch D. In planta function of compatible solute transportes of the AtProT family. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:787–796. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestichelli LJJ, Gupta RN, Spencer ID. The biosynthetic route from ornithine to proline. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:640–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosens NH, Thu TT, Iskandar HM, Jacobs M. Isolation of the ornithine- δ- aminotransferase cDNA and effect of salt stress on its expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:263–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funck D, Stadelhofer B, Koch W. Ornithine-δ-aminotransferase is essential for arginine catabolism but not for proline biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizhov N, Ábrahám E, Ökresz L, Blickling S, Zilberstein A, Schell J, Koncz C, Szabados L. Differential expression of two P5CS genes controlling proline accumulation during salt-stress requires ABA and is regulated by ABA1, ABI1 and AXR2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1997;12:557–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Székely G, Ábrahám E, Cséplo Á, Rigo G, Zsigmond L, Csiszár J, Ayaydin F, Strizhov N, Jásik J, Schmelzer E, Koncz C, Szabados L. Duplicated P5CS genes of Arabidopsis play distinct roles in stress regulation and developmental control of proline biosynthesis. Plant J. 2008;53:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders PM, Bui AQ, Weterings K, McIntire KN, Hsu YC, Lee PY, Truong MT, Beals TP, Goldberg RB. Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male sterile mutants. Sex Plant Reprod. 1999;11:297–322. doi: 10.1007/s004970050158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MP. Differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen. Stain Technol. 1969;44:117–122. doi: 10.3109/10520296909063335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R, Slovin JP, Chen C. A simplified method for differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen grains. Int J Plant Biol. 2010;1:e13. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Brousseau SA, McCormick S. A compendium of methods useful for characterizing Arabidopsis pollen mutants and gametophyticallyexpressed genes. Plant J. 2004;39:761–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hare PD, Cress WA, Van Staden J. Dissecting the roles of osmolyte accumulation during stress. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:535–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertel L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Bioinformatics: Advances in; 2008. p. 420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J, Lee YH, Tegeder M. Distinct expression of members of the LHT amino acid transporter family in flowers indicates specific roles in plant reproduction. Sex Plant Reprod. 2008;21:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s00497-008-0074-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis eFP Browser. http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp.

- Genevestigator. https://www.genevestigator.com.

- Bock KW, Honys D, Ward JM, Padmanaban S, Nawrocki EP, Hirschi KD, Twell D, Sze H. Integrating membrane transport with male gametophyte development and function through transcriptomics. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1151–1168. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidereit A, Scholz-Starke J, Büttner M. Functional characterization and expression analyses of the glucose-specific AtSTP9 monosaccharide transporter in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:182–190. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SeedGenes Project. http://seedgenes.org.

- Muralla R, Lloyd J, Meinke D. Molecular foundations of reproductive lethality in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2011;6:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare PD, Cress WA. Metabolic implications of stress-induced proline accumulation in plants. Plant Growth Reg. 1997;21:79–102. doi: 10.1023/A:1005703923347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palanivelu R, Brass L, Edlund AF, Preuss D. Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell. 2003;114:47–49. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V, Altamura MM, Falasca G, Costantino P, Cardarelli M. Auxin regulates Arabidopsis anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and filament elongation. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1760–1774. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Howden R, Twell D. The Arabidopsis thaliana gametophytic mutation gemini pollen1 disrupts microspore polarity, division asymmetry and pollen cell fate. Development. 1998;125:3789–3799. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CN Jr, Via LE. A rapid CTAB DNA isolation technique useful for RAPD fingerprinting and other PCR applications. Biotechniques. 1993;14:748–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL. Arabidopsis: an Atlas of Morphology and Development. Berlin & New York: Springer-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther stained with Alexander’s stain. Close up of a p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther stained with Alexander’s stain. The small and misshaped pollen grains are clearly visible, within a p5cs1 p5cs2/P5CS2 anther, as non-stained pollen pollen grains alongside wild type-like, red stained, pollen grains. Bar = 50 μm.

Figure S2. In vitro germination assays of pollen from p5cs1 single mutants. To evaluate possible defects in pollen viability of a mutant bearing a single mutation in P5CS1 gene, pollen from a homozygous knockout p5cs1 mutant was incubated in vitro on germination medium and scored for germination. (A) Percentage of germinated versus total pollens (germinated + non germinated), including both large and small pollen grains (right column), compared to wild type (left column). (B) Percentage of large (middle column), small (right column), and wild type pollen (left column) versus large (middle column), small (right column) and wild type (left column) total germinated pollen. Values in (A) and (B) represent the means of four independent experiments ± SE.