Abstract

This pilot study assessed the determinants of engagement in HIV care among Zambian patients new to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, and the effect of an intervention to increase medication adherence. Participants (n = 160) were randomized to a 3-month group or individual intervention utilizing a crossover design. Psychophysiological (depression, cognitive functioning, health status), social (social support, disclosure, stigma), and structural (health care access, patient-provider communication) factors and treatment engagement (adherence to clinic visits and medication) were assessed. Participants initially receiving group intervention improved their adherence, but gains were not maintained following crossover to the individual intervention. Increased social support and patient-provider communication and decreased concern about HIV medications predicted increased clinic attendance across both arms. Results suggest that early participation in a group intervention may promote increased adherence among patients new to therapy, but long-term engagement in care may be sustained by both one-on-one and group interventions by health care staff.

Keywords: behavioral intervention, engagement in care, HIV, medication adherence, Zambia

Determinants of Engagement in HIV Treatment and Care among Zambians new to Antiretroviral Therapy Linking and retaining patients to HIV treatment has emerged as a priority for HIV prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa, a region which is home to 22.5 million persons living with HIV (PLWH), or 68% of HIV cases globally (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], 2010). In Zambia, one of the nations with the highest HIV prevalence, the public health system provides HIV treatment and antiretroviral (ARV) distribution through large referral health facilities, smaller provincial hospitals, and community health centers (CHCs). No-cost ARV distribution has been decentralized to CHCs to encourage patients to utilize local clinics rather than hospitals to reduce crowding, yet fears of HIV-related stigma and discrimination and anxiety about confidentiality cause some patients to begin testing, diagnosis, and initial treatment in public hospitals and subsequently to transition to CHCs (Jones et al., 2009). For these patients, critical elements of HIV care are to ensure that they continue to receive services and treatment over time, not only at the hospital, but also as they transition to the CHC and that they maintain adherence to their medication and treatment regimens.

In 2009, more than half of those who were eligible (283,000 HIV-infected Zambian adults and children were on medication) had initiated ARV treatment (ART) and were primarily found to be adherent (as measured by pharmacy pick-up; Stringer, 2008). Yet, despite availability, some failed to benefit from treatment because they were poorly engaged in treatment and the risk ratio was approximately double (1.4-2.9, adjusted) that of optimal adhering patients. In this population, mortality was associated with being lost to follow-up within the first 90 days of ART, while among those who survived at least 12 months, 91% had more than 80% adherence (Stringer, 2008). Recent initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa have focused on linkage to care but, ultimately, clients must both value and want care and support services to be successfully linked and retained (UNAIDS, 2010). Engagement strategies play a critical role in HIV care, linking clients with health systems offering treatment and helping patients to achieve an undetectable viral load (Cheever, 2007) and remain healthy. In addition, early establishment of HIV-related health behaviors may enhance adherence (Jones et al., 2010) and reduce the potential for the development of a resistant virus (Walshe et al., 2010).

Individual, social, and structural factors in sub-Saharan Africa impact linkage to and engagement in care, which has been associated with viral suppression and reduced viral burden (Mugavero et al., 2012). Stigma and negative attitudes in health care settings, both perceived and enacted, may reduce access to care and HIV medication adherence (Murray et al., 2009; Nachega et al., 2004), for example, health care may be perceived as supportive or stigmatizing and inaccessible (Rogers et al., 2006). Aspects of the patient-provider relationship, such as patient concerns and beliefs about HIV medication and difficulty understanding and carrying out the medication regimen, have been associated with non-adherence to ART (Fogarty et al., 2002; Ickovics & Meisler, 1997). Similarly, lack of social support and perceived and enacted stigma in the community have been demonstrated as barriers to care (Nachega et al., 2004). Increased social support has been shown to improve adherence to HIV medication and has been linked to an improved quality of life for PLWH (Ncama et al., 2008; Peltzer, Friend-du Preez, Ramlagan, & Anderson, 2010).

The purpose of this study was to examine the determinants of patient engagement in care and to enhance engagement in care and adherence to HIV treatment in new ARV users in Lusaka, Zambia. The relationship between psychophysiological (depression, cognitive functioning, health status), social (social support, disclosure, stigma), and structural (health care access, patient-provider communication) factors and engagement in treatment (health care use, medication adherence) was examined. A group and an individual intervention were developed and implemented, and their impact on engagement in treatment was assessed. To date, few intervention studies have addressed factors underlying health care engagement in Zambia (e.g., Cantrell et al., 2008; Torpey et al., 2008), and this study sought to extend previous research in sub-Saharan Africa (Bärnighausen et al., 2011; Byakika-Tusiime et al., 2009; Hatcher et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2006). It was hypothesized that individuals with lower psychophysiological functioning and limited social and structural support would demonstrate lower treatment engagement, as measured by health care use and adherence. It was further hypothesized that an intervention targeting social and structural factors would enhance treatment engagement.

Methods

Design

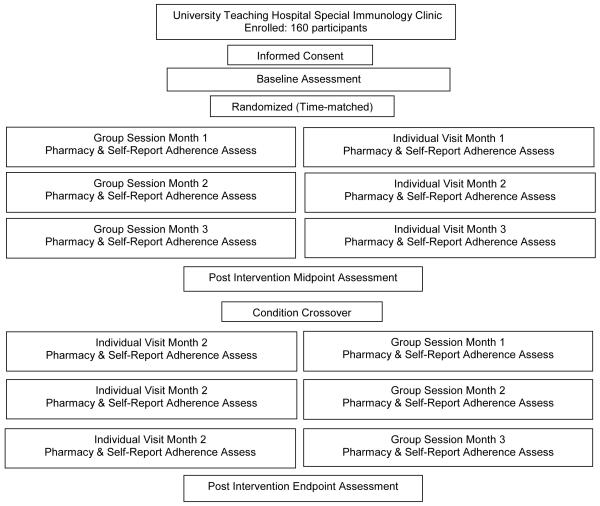

This study was a randomized clinical trial, assessing the effect of intervention assignment on engagement in care and determining the relationship of psychophysiological, social, and structural factors with study outcomes. Participants were randomly assigned to start in the group or individual intervention condition and crossed over to the alternate condition after three sessions. Randomization was accomplished using a computer-generated list of random numbers to which participants were sequentially matched during enrollment. The investigators were blind to study assignment and were not involved in provision of the intervention or assessments. Assessment and intervention staff were multilingual nurses trained in assessment administration and were conversant in the primary local languages (Bemba, Nyanja, or English). Institutional review board and ethics committee approvals were obtained in accordance with the provisions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the University of Zambia regarding the conduct of research prior to study onset.

Participants

This study enrolled 160 HIV-infected Zambians 18 years of age or older. Participants were recruited September 2006 to June 2008 from the Lusaka metropolitan area at the University Teaching Hospital Immunology Clinic at the University of Zambia School of Medicine. Interested recruits were screened for eligibility: HIV seropositive, ARV use duration less than 24 consecutive months, and no previous use of ARVs (e.g., nevirapine associated with pregnancy). Participants were administered all assessments to eliminate the requirement of literacy for study participation. Prior to study enrollment, participants provided informed consent and were then randomly assigned to a study condition. Participants were provided with monetary compensation (Kwacha 20,000, ~US$5) for travel and associated expense.

All Zambians diagnosed with HIV are eligible to receive the standard of care: no-cost treatment and medication. The standard of care in Zambia for treatment is monthly health care provider (physician or clinic officer) visits over the first 6 months of medication provision to assess health status, tolerance, and adherence, and patients obtain monthly prescription refills during this period. Thereafter, patients are provided with 3 months of medication at each pharmacy visit and attend provider visits every 3 months, followed by visit every 6 months at the end of the first year of treatment. Prior to the initiation of ART, CD4/CD8 and liver function tests are conducted. At the time of this study, almost all participants received Triomune – 30/40, one of the most frequently prescribed treatments in Africa, a generic fixed-dose combination of stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC) and nevirapine (2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and 1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor). A minority of participants were not maintained on nevirapine due to negative reactions. These generic fixed-dose combinations began with a 2-week run-in of nevirapine at low dose to ensure drug tolerance, followed by d4T and 3TC separately, followed by Triomune.

Measures and Intervention

Adaptation and pilot testing of assessments and intervention materials

Focus group data (n = 24; 3 language groups, 12 men, 12 women) were used to adapt the assessments and intervention content to the Zambian context, and all assessment instruments and intervention elements were translated, back translated, and reviewed for cultural appropriateness and comprehension. Intervention sessions were conducted using a combination of local languages (Bemba and Nyanja) and English, due to the mixture of audience languages (there are 73 dialects and 3 primary regional languages in Zambia). The cultural translation process has been described (Jones et al., 2010).

Assessment protocol and battery

Participants in both conditions were given 6 monthly assessments of engagement in care and self-reported adherence (previous 4 days’ medication adherence and missed doses over 3 months). Additionally, participants were administered comprehensive questionnaires inquiring about demographic and health-related characteristics at baseline, midpoint (approximately 3 months post-baseline, pre-crossover), and study endpoint (approximately 6 months post-baseline). The midpoint assessment was added after the first cohorts had crossed-over and was available to only 100 participants.

Demographic and Health Characteristics

Demographics

Demographic items assessed included age, ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, marital status, number of children. HIV specific items included partner serostatus, mode of infection, approximate date of HIV diagnosis, time on ARV medication, HIV serostatus disclosure (number of persons to whom status was disclosed), and clinic attendance rates.

Brief Health and Functioning Questionnaire (BHFQ)

This 19-item quality-of-life scale, designed for HIV-infected persons, was used to assess measured multiple dimensions of health and well-being (health perceptions, pain, physical, role, social and cognitive functioning, mental health, energy, health distress, and quality of life; Huba & Melchior, 1997). The BHFQ is internally consistent (Bozzette, Hays, Berry, Kanouse, & Wu, 1995), correlated with concurrent measures of health, and predicts disease progression over time (internal consistency of multi-item scales, Cronbach’s alpha average > .78).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961), a 21-item Likert-type scale, is designed to measure depression within the previous 7 days. The scale assesses affective, behavioral, and somatic components associated with depression. Participants rate items from 0 to 3, resulting in a maximum score of 63. Scores on subscales (somatic and cognitive) and full scales are the sum of items. Scores indicate minimal depression (< 10), mild to moderate depression (10-18), moderate to severe depression (19-29), and severe depression (≥ 30).

Social Functioning

Stigma Indicators Questionnaire (SIQ)

Stigma was assessed to identify perceived and enacted stigma (discrimination) using the Stigma Indicators measure (Nyblade et al., 2008). Perceived community stigma (subscale 0-17), enacted stigma (subscale 0-18), and stigma enacted in a health care setting (subscale 0-14) were reported. Disclosure was measured in the demographics questionnaire.

Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ)

The SSQ (Zich & Temoshok, 1987) is an 8-item Likert-type scale that includes a subscale assessing Perceived Social Support. Participants rated the extent to which others (including peers) were perceived as available to assist with HIV illness, including health care and overall assistance (range 8-40).

Engagement in Health Care

Adherence Attitude Inventory (AAI)

The AAI is a 28-item scale assessing attitudes regarding HIV-related adherence. The Patient-Provider Communication subscale (alpha internal consistency 0.89; Lewis & Abell, 2002) addressed mutual exchange of thoughts, attitudes, and feelings regarding adherence, service delivery, and access to care. The subscale consists of 7 items with a 7-point scale ranging from none of the time to all of the time (range 7-49). Frequency of clinic visits was assessed in Demographics and the BHFQ.

Clinic attendance and adherence

Engagement in care was operationalized as clinic attendance and self-reported adherence. Clinic visits in the last 4 weeks was assessed by patient self-report; change in clinic attendance was dichotomized into those who increased their number of provider visits per month over the course of the study (post – pre > 0) and those who did not increase or decreased their number of visits (post – pre ≤ 0). Monthly self-reported ARV use was assessed using a 4-day self-report measure, AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Questionnaire for Adherence to Anti-HIV Medications (Chesney, 2000) and reported missed doses over the previous 3 months. Participants’ adherence over time was also dichotomized into improved adherence and unchanged/reduced adherence.

Intervention Conditions

Participants in both conditions attended a monthly visit with a health care provider to review their medication use and pharmacy refill history over the previous month and address challenges and solutions to adherence. The intervention was developed from previous research (Jones et al., 2010) and utilized a combination of strategies targeting health literacy, HIV, and medication adherence and transmission information. The study utilized the Information Motivation Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model of ARV Adherence, in which the underlying components of medication adherence (adherence related-information, motivation, and behavioral skills) function together to promote adherence (Fisher, Fisher, Amico, & Harman, 2006). Participants were provided with information on treatment and adherence (realistic expectations for medication, side effects, treatment duration, and the relationship between ARVs, viral load, CD4+ T cell count, and disease progression) that enhance treatment motivation (positive attitudes on medication and engagement in treatment) and skills (increased patient-provider communication, coping with side effects, use of pill reminders) to increase adherence to treatment and retention in care.

Provision of intervention

Staff (n = 4) were trained by the study investigators in the provision of the intervention, using a manualized protocol described in earlier literature (Jones et al., 2010). Staff members provided the intervention on a rotating basis to counteract the influence of a specific provider, although the number of study participants was too small to address provider-specific influences. Quality control of tape recordings of study sessions by the senior staff member and investigators was used to ensure consistency of staff delivery of the intervention to all participants.

Group intervention

Participants attended 3 monthly group sessions (10 participants per group) designed to facilitate adherence skills and enhance uptake of information though repeated presentation. Sessions lasted 90 minutes and focused on HIV and medication knowledge, concerns or barriers in the use of ARVs, and challenges or solutions to their use. Group interaction maximized the impact of peer and facilitator support; all facilitators were nurses trained to administer the intervention and supervised by a senior nurse (site coordinator).

Individual intervention

Participants attended a one-on-one intervention with a health care provider and visits were time-matched monthly individual sessions. Sessions included the same material as addressed in the group presented, but on an individual basis, as well as additional time-matched videos on stress management and healthy nutrition, to coincide with the length of the group intervention sessions.

Data Analyses

This study utilized an intent-to-treat analysis, which included everyone who enrolled in the trial, regardless of the level of participation. This analysis ignores the effects of drop out, and has been used rather than a subset analysis, which may increase the chance of a type I error. Pairwise deletion of missing data was employed when necessary. Demographic comparisons were completed using baseline data, and outcomes were analyzed using monthly adherence and engagement assessments as well as baseline, midpoint, and endpoint data. However, because the midpoint assessment was not available to every participant, adherence was analyzed using 3-month data instead of midpoint data. A total of 15 participants withdrew from the initial group intervention condition, and 23 withdrew from the initial individual intervention condition.

To examine engagement in care, this study utilized chi-square tests of independence to determine differences in adherence between groups, McNemar’s test to determine differences in adherence within groups over time, and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare changes in psychosocial predictors between categories of improved adherence and unchanged/reduced adherence. Mann-Whitney U tests were also used to determine factors associated with increased clinic visits, and associated factors were examined using logistic regression to assess predictive ability. All tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 software at a two-tailed level of significance of p = .05.

Results

Participant demographics by condition are outlined in Table 1. Participants were primarily married (53%), and most had been on ARVs for approximately 15 months. The majority (82%) reported living in extreme poverty (under $5,000 yearly). While 60% had completed secondary school, many (40%) were unemployed. At baseline, nearly one third had disclosed their HIV serostatus to three or fewer people.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants by Initial Condition Assignment (n = 160)

| Characteristic | Individual | Group | χ 2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | 1.2 | .34 | ||||

| Male | 37 | 45 | 41 | 53 | ||

| Female | 46 | 55 | 36 | 47 | ||

| Age (Range) | .09 | .96 | ||||

| 18-35 | 44 | 53 | 39 | 51 | ||

| 36-50 | 33 | 40 | 32 | 42 | ||

| 51-60 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Ethnicity | 8.7 | .03 | ||||

| Bemba | 25 | 30 | 13 | 17 | ||

| Nsenga | 9 | 11 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Lozi | 2 | 2 | 9 | 12 | ||

| Other | 47 | 57 | 49 | 64 | ||

| Years of Education | 6.2 | .05 | ||||

| Primary | 10 | 12 | 17 | 24 | ||

| Secondary | 50 | 60 | 46 | 60 | ||

| College Level | 23 | 28 | 12 | 16 | ||

| Employment | .05 | .82 | ||||

| Full or part time | 50 | 60 | 45 | 58 | ||

| Unemployed | 33 | 40 | 32 | 42 | ||

| Annual Income | 1.4 | .50 | ||||

| < $5,000 | 68 | 83 | 62 | 82 | ||

| $5,001 - $9,999 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | ||

| $10,000 or greater | 10 | 12 | 7 | 9 | ||

| Marital Status | 1.4 | .51 | ||||

| Married | 44 | 53 | 41 | 53 | ||

| Not Married or Divorced | 22 | 27 | 25 | 33 | ||

| Widowed | 17 | 21 | 11 | 14 | ||

| HIV Serostatus of Partner | .52 | .77 | ||||

| Infected | 30 | 46 | 27 | 45 | ||

| Uninfected | 28 | 43 | 24 | 40 | ||

| Do Not Know | 7 | 11 | 9 | 15 | ||

|

Participant Disclosure of

Serostatus |

.05 | .82 | ||||

| To 3 or fewer people | 33 | 40 | 32 | 42 | ||

| To more than 3 people | 50 | 60 | 45 | 58 | ||

| Travel Time to Clinic | .29 | .59 | ||||

| 1 hour or less travelling | 53 | 64 | 46 | 60 | ||

| More than 1 hour travelling | 30 | 36 | 31 | 40 | ||

| Time at Clinic Appointments | .79 | .38 | ||||

| 1 hour or less at visit | 9 | 11 | 12 | 16 | ||

| More than 1 hour at visit | 74 | 89 | 65 | 84 | ||

Note. Bolded values = p < .05.

Adherence

At baseline, self-reported adherence was very high for all participants (99% reported perfect adherence to medication over a 4-day period). The percentage of participants who reported consistent adherence over the previous 3 months was high for both conditions (88% group, 89% individual), and there was no difference between conditions (X2 < .001, p = 1.0). At 3-month follow-up, the proportion reporting consistent adherence over the previous 3 months increased in the group condition (98%, McNemar’s test, p = .02) but it did not in the individual condition (88%, McNemar’s test, p = 1.0). One month after crossover of condition, consistent medication adherence returned to near baseline levels in both conditions (85% group, 86% individual) and there was no difference between conditions (X2 < .001, p = .99). From midpoint to follow-up, the proportion reporting consistent adherence did not improve in either condition.

In order to evaluate the relationship between changes in psychosocial predictors and adherence, scores were examined over time. No differences were observed in the changes in predictor values from baseline to midpoint and midpoint to follow-up. Associations were explored between changes in predictor values and improvement in adherence. Increased social support (Mann-Whitney U test, p = .04) and increased belief in the necessity of HIV medication (Mann-Whitney U test, p = .01) were associated with increased adherence, such that participants reporting increased social support and increased belief in the necessity of HIV medication from baseline to midpoint also reported improved adherence.

Engagement in Care

To determine which components of the intervention may have been related to increased clinic visits, a series of Mann-Whitney U tests were performed examining changes in predictor variables across categories of increased and decreased/unchanged clinic visits, with all moderately associated (p < .25) variables being considered (see Table 3). Condition, overall severity of illness, and time on ART were also considered as possible predictors, regardless of level of association. Logistic regression models were constructed to determine which associated factors would be able to best predict an increase in clinic visits during the first 3 months of the study, after crossover, and across the duration of the study.

Table 3.

Predictors Associated with Increased Provider Visits (Mann-Whitney U Test) and Logistic Regression Predicting Increase in Provider Visits

| Predictors associated with increased provider visits | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Baseline-Midpoint Predictor (p) |

Midpoint-Endpoint Predictor (p) |

Baseline-Endpoint Predictor (p) |

| Concerns about HIV medication (.06) |

Beliefs about health care in general (.09) |

Beliefs about the necessity of HIV medication (.13) |

| Perceived stigma in a health care environment (.13) |

Social support (.02) | Concerns about HIV medication (.01) |

| Social support (.01) | Perceived stigma in a health care environment (.17) |

|

| Patient-provider communication (.05) |

Social support (.08) | |

| Patient-provider communication (.06) |

Cognitive depression (.02) Total depression (.10) |

|

| Logistic regression predicting increase in provider visits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B(SE) | Wald(df) | p | OR(95% CI) |

| Baseline-Midpoint | ||||

| Decreased stigma in a health care environment |

−2.7(1.2) | 5.2(1) | .022 | .07(.01, .68) |

| Increased social support |

.11(.06) | 3.9(1) | .049 | 1.12(1.0, 1.3) |

| Midpoint-Endpoint | ||||

| Decreased stigma in a health care environment |

−1.9(.84) | 4.9(1) | .027 | .16(.03, .81) |

| Baseline-Endpoint | ||||

| Decreased concerns about HIV medication |

−.15(.04) | 11.5(1) | .001 | .86(.79, .94) |

| Increased social support |

.05(.02) | 5.4(1) | .020 | 1.1(1.0, 1.1) |

| Increased patient- provider communication |

.04(.02) | 4.5(1) | .035 | 1.04(1.0, 1.1) |

From baseline to midpoint, decreased enacted stigma in a health care environment and increased social support predicted increased clinic visits (Nagelkerke R2 = .28, model χ2 = 14.3, p = .003). From midpoint to endpoint, only decreased enacted stigma in a health care environment predicted increased clinic visits (Nagelkerke R2 = .16, model χ2 = 7.3, p = .007). Across the duration of the study, decreased concern about HIV medication, increased social support, and increased patient-provider communication predicted increased clinic visits (Nagelkerke R2 = .26, model χ2 = 21.9, p < .001).

Discussion

This study sought to examine engagement in care, targeting factors associated with adherence and clinic attendance (patient-provider communication, depression, stigma, social support, and attitudes about medication), and compared group and individual interventions with immediate and delayed onset. Participants enrolled in the immediate-onset group condition demonstrated increased medication adherence; however, they failed to maintain gains in adherence after crossover to the individual condition. Participants in the immediate onset individual condition did not demonstrate increased adherence, even after crossover to the group condition. Stigma, social support, concerns about medication, and patient-provider communication predicted increased clinic attendance among participants in both conditions.

While most participants reported consistent adherence, those who were non-adherent at baseline had difficulty achieving and maintaining adherence during the study, suggesting that maintaining long-term adherence may require a continuous rather than single-dose intervention strategy. Early intervention with a group strategy and continuous provider involvement may provide support for the establishment of health behaviors that promote successful adherence to lifelong use of medication (Knowlton et al., 2010; Thrun et al., 2009). However, failure to maintain gains in adherence may be associated with study design, such as variability in standard of care (de Bruin et al., 2010); poor outcomes have been obtained in numerous ARV adherence studies (Simoni, Amico, Pearson, & Malow, 2008). In addition, a meta-analysis by de Bruin and colleagues (2010) found that controlling for variability in the standard care provided to control groups might lead to more accurate estimates of intervention effects.

Stigma, social support, concerns about medication, and patient-provider communication predicted increased clinic attendance among participants in both conditions. Both group and individual conditions provided a forum for open discussion of HIV concerns, which may typically be avoided due to perceived stigma (Jones et al., 2009). In fact, increased one-on-one patient-provider interaction and support group participation have both been found to predict health behaviors (Ncama et al., 2008). Once diagnosed with HIV infection, the role of the patient-provider relationship appears essential to engagement in care and the achievement of optimal adherence (Mills et al., 2006).

Findings support the use of the IMB model to increase engagement in care among HIV-infected populations in urban Lusaka, Zambia. HIV support groups are common in Zambia in the form of “Post-Test Clubs” and their use as a forum for ARV support could also be a cost-effective strategy. Forums to encourage the establishment of health behaviors or to target behavioral change to increase engagement in care could be used for patients new to care. Additionally, groups stimulate open sharing and fellowship and provide increased opportunities to discuss issues with health care practitioners. As in many countries, typical provider visits are 10 minutes or less, and the interventions provided an hour or more to address questions and HIV-related medical information. As previously found (Bärnighausen et al,. 2011; Hatcher et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2009; Ncama et al., 2008), this study provided evidence for the importance of targeting social support, stigma, issues surrounding medication, and communication with providers to increase engagement in HIV treatment and care. The role of health care staff in provision of HIV information and medication adherence support should continue to be expanded as an adjunct to regular medical visits. Future studies should address the critical role of health care staff/providers in supporting medication adherence and explore the feasibility of larger, more cost effective group-intervention strategies.

Limitations to this study include the lack of biological data associated with adherence (e.g., viral load, CD4+ T cell count); subsequent research in this population should include viral load assessment and pill count as an additional measure of medication compliance. Self-reported adherence may have been inflated due to participants’ desires to please the interviewer.

Health care providers in Zambia play an essential role in facilitating the establishment and maintenance of health behaviors following diagnosis. Public health programs should continue to address the collaborative role of nurses, clinic staff, and medical providers to enhance HIV outcomes. Community health care providers and their patients enjoy a unique relationship that can be used within an intervention to leverage improved engagement in care.

Clinical Considerations.

Early engagement in care is vital to the efficacy of ARV treatment regimens.

The patient-provider relationship is vital and may provide a level of support necessary to maintain long-term adherence to ARV medication. Good patient-provider communication appears to be a necessary component for successful engagement in care.

The role of clinic staff in provision of HIV information and medication adherence support should continue to be expanded as an adjunct to regular medical visits.

The feasibility of larger, more cost effective group-intervention strategies should be considered by clinics serving HIV-infected communities in resource poor settings.

Figure 1.

Flowchart

Figure 2.

Consort diagram

Table 2.

| Initial Condition | Individual n (%) |

Group n (%) |

X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 73 (89%) | 68 (88%) | .00 | .99 |

| 1 month | 58 (85%) | 62 (95%) | 2.8 | .10 |

| 3 months | 58 (87%) | 65 (98%) | 4.3 | .04 |

| Baseline - 3 months, McNemar’s test | p = .99 | p = .02 | ||

| Crossover |

Group

n (%) |

Individual

n (%) |

X2 | p |

| 4 months | 51 (85%) | 55 (86%) | .00 | .99 |

| 6 months | 51 (91%) | 54 (86%) | .39 | .54 |

| Endpoint | 48 (83%) | 52 (85%) | .01 | .91 |

| 4 months- Endpoint, McNemar’s test | p = .99 | p = .51 |

Self-Reported Consistent Adherence (Previous 3 Months)

Consistent adherence = No missed doses.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nurses, physicians, and patients participating in the study, without whom the study would not have been possible. This study was supported by a National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases grant, no. R21AI067115.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Deborah L. Jones, Dept. of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

Isaac Zulu, Center for Disease Control & Prevention Lusaka, Zambia.

Szonja Vamos, Dept. of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Miami, FL, USA.

Ryan Cook, Dept. of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

Ndashi Chitalu, University Teaching Hospital Lusaka, Zambia.

Stephen M. Weiss, Dept. of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Miami, FL, USA.

References

- Bärnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, Peoples A, Haberer J, Newell ML. Interventions to increase antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11:942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzette SA, Hays RD, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Wu AW. Derivation and psychometric properties of a brief health-related quality of life instrument for HIV disease. Journal of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes and Retrovirology. 1995;8:253–265. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006. doi:10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byakika-Tusiime J, Crane J, Oyugi JH, Ragland K, Kawuma A, Musoke P, Bangsberg DR. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-Plus family treatment model: Role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS & Behavior. 2009;13(Suppl. 1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9546-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, Lawson-Marriott S, Washington S, Chi BH, Stringer JS. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49:190–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: Their lives depend on it. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44:150–152. doi: 10.1086/517534. doi:10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;30:S171–S176. doi: 10.1086/313849. doi:10.1086/313849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin M, Viechtbauer W, Schaalma HP, Kok G, Abraham C, Hospers HJ. Standard care impact on effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(3):240–250. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.536. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Fisher W, Amico K, Harman J. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology. 2006;25:462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: A review of published and abstract reports. Patient Education & Counseling. 2002;46:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher A, de Wet J, Bonell CP, Strange V, Phetla G, Proynk PM, Hargreaves JR. Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programs: Lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Education Research. 2011;26:542–555. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq057. doi:10.1093/her/cyq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huba GJ, Melchior LA, The Measurement Group, & HRSA/HAB’s SPNS Cooperative Agreement Steering Committee Module 17: Brief Health and Functioning Questionnaire. 1997 Retrieved from http://www.themeasurementgroup.com/modules/mods/module17.htm.

- Ickovics JR, Meisler AW. Adherence in AIDS clinical trials: A framework for clinical research and clinical care. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00041-3. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/globalreport/documents.htm.

- Jones D, Zulu I, Mumbi M, Chitalu N, Vamos S, Gomez J, Weiss SM. Strategies for living with the challenges of HIV and antiretroviral use in Zambia. International Electronic Journal of Health Education. 2009;12:253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Chitalu N, Ndubani P, Mumbi M, Weiss SM, Villar-Loubet O, Waldrop-Valverde D. Sexual risk reduction among Zambian couples. SAHARA Journal. 2010;6:69–75. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724932. doi:10.1080/17290376.2009.9724932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton AR, Arnsten JH, Eldred LJ, Wilkinson JD, Shade SB, Bohnert AS, Purcell DW. Antiretroviral use among active injection-drug users: The role of patient–provider engagement and structural factors. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24:421–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0240. doi:10.1089/apc.2009.0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SJ, Abell N. Development and evaluation of the Adherence Attitude Inventory. Research on Social Work Practice. 2002;12:107–123. doi:10.1177/104973150201200108. [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, Bangsberg DR. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. doi:10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, Crane HM, Zinski A, Willig JH, Saag MS. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: Implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;59(1):679–690. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2. doi:10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Semrau K, McCurley E, Thea DM, Scott N, Mwiya M, Bolton P. Barriers to acceptance and adherence of antiretroviral therapy in urban Zambian women: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21:78–86. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032643. doi:10.1080/09540120802032643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega JB, Stein DM, Lehman DA, Hlatshwayo D, Mothopeng R, Chaisson RE, Karstaedt AS. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2004;20:1053–1056. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.1053. doi:10.1089/aid.2004.20.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ncama BP, McInerney PA, Bhengu BR, Corless IB, Wantland DJ, Nicholas PK, Davis SM. Social support and medication adherence in HIV disease in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45:1757–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.06.006. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyblade L, MacQuarrie K, Kwesigabo G, Jain A, Kajula L, Philip F, Mwambo J. Moving forward: Tackling stigma in a Tanzanian community. 2008 Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADL579.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Friend-du Preez N, Ramlagan S, Anderson J. Antiretroviral adherence among HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-111. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Meundi A, Amma A, Rao A, Shetty P, Antony J, Shetty AK. HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, perceived benefits, and risks of HIV testing among pregnant women in rural Southern India. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2006;20:803–811. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.803. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.20.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Amico RK, Pearson CR, Malow R. Strategies for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the literature. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2008;10:515–521. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0083-y. doi:10.1007/s11908-008-0083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer JS. Rapid scale-up of HIV care and treatment services in Zambia: A challenge to ART adherence and retention in care. Paper presented at International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Conference; New Orleans, LA. Nov, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun M, Cook PF, Bradley-Springer LA, Gardner L, Marks G, Wright J, Golin C. Improved prevention counseling by HIV care providers in a multisite, clinic-based intervention: Positive STEPs. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:55–66. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.1.55. doi:10.1521/aeap.2009.21.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torpey KE, Kabaso ME, Mutale LN, Kamanga MK, Mwango AJ, Simpungwe J, Mukadi YD. Adherence support workers: A way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe L, Saple DG, Mehta SH, Shah B, Bollinger RC, Gupta A. Physician estimate of antiretroviral adherence in India: Poor correlation with patient self-report and viral load. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(3):189–193. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0208. doi:10.1089=apc.2009.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zich J, Temoshok L. Perceptions of social support in men with AIDS and ARC: Relationships with distress and hardiness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17:193–215. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1987.tb00310.x. [Google Scholar]