Abstract

BACKGROUND

The ability to distinguish increased platelet destruction from platelet hypo-production is important in the care of patients with bone marrow failure syndromes and patients receiving high dose chemotherapy. The measurement of immature circulating platelets based on RNA content using an automated counter is now feasible. This study evaluated the impact of recent platelet transfusion on measurement of immature platelet parameters.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

The immature platelet fraction (IPF) and absolute immature platelet number (AIPN) were measured using the Sysmex XE-5000 analyzer prior to and following platelet transfusion in 9 transfusion-dependent patients with marrow failure secondary to aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia or transplantation conditioning. IPF and AIPN were also measured serially over 5 days of storage in 3 plateletpheresis components collected from normal donors.

RESULTS

Platelet transfusion did not significantly change the mean AIPN in transfused patients. In contrast, IPF decreased significantly from 6.6 ±4.6% at day -1 to 2.3 ±1.4% at day 0 before returning to 4.3 ±2.3% at day +1. In the platelet component, AIPN and IPF% increased significantly over 5 days of storage, most likely due to an artifact of the staining and detection process for stored platelets, no longer detected in vivo once the platelets were transfused.

CONCLUSION

Platelet transfusion decreases the IPF due to the resultant increase in circulating platelet count. However, platelet transfusion does not change the circulating absolute immature platelet number (AIPN), validating this assay as a reflection of ongoing platelet production by the bone marrow in various clinical settings, regardless of proximity to platelet transfusion.

Introduction

Ablative or highly myelosuppressive therapies are utilized prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and to treat an array of hematologic malignancies. This approach often consists of repeated cycles of high dose therapy, possibly followed by a series of autologous and/or allogeneic stem cell transplants. As patient outcomes improve and intensive therapies are applied to a broader group of patients, increasing demands are placed on transfusion services for the provision of platelet components. Prediction of time to marrow engraftment and informed decision-making regarding the duration and intensity of platelet transfusion requirements have been major challenges in this setting. Platelet recovery often lags behind neutrophil engraftment, and the ability to distinguish inadequate platelet production from platelet consumption due to bleeding, fever, or graft-versus-host disease can be challenging. The ability to measure production of new platelets from the marrow using a simple blood test, analogous to measurement of red cell production using a reticulocyte count, may help predict incipient marrow recovery and help distinguish platelet production from platelet consumption as causes of thrombocytopenia.

Immature and recently-released platelets contain RNA, analogous to reticulocytes in the erythroid lineage, but this RNA degrades rapidly over time due to lack of replenishment in anucleate circulating platelets. The detection of RNA-containing platelets using the recently-developed Sysmex XE-5000 blood cell analyzer allows measurement of the immature platelet fraction (IPF) as a percentage of the total platelet population, and calculation of the absolute immature platelet number (AIPN).1 Briggs et al.2 evaluated the clinical utility of the IPF as a measure to predict marrow recovery and platelet transfusion dependency in a cohort of patients undergoing stem cell transplantation. They prospectively evaluated 15 autologous or allogeneic transplant patients by measuring serial IPF percent and platelet count and showed that IPF can be used as a parameter to identify the recovery phase from thrombocytopenia several days prior to an actual increase in total circulating platelet counts. Takami et al.3 similarly showed that IPF transiently increased in the early post-transplant period in all patients who eventually engrafted, which may reflect an explosive increase in platelet production at the beginning of engraftment.

Recently, Barsam et al.4 demonstrated the utility of the absolute immature platelet number (AIPN), which represents the number of newly released platelets (IPF % x the platelet count), to determine real time marrow thrombopoiesis in patients with putative ITP, thereby avoiding the need for bone marrow examination to distinguish hypo-productive from consumptive thrombocytopenia.

However, neither of these investigators examined the impact of platelet transfusions on measurement of the AIPN. In patients with profound thrombocytopenia, it is important to establish whether or not platelet transfusion will result in an increase in AIPN due to allogeneic immature platelets, preventing accurate assessment of a patient’s ongoing autologous platelet production. In this study, we asked whether platelet transfusions will impact the measurement of the AIPN, and thus whether the AIPN can be used to assess marrow thrombopoiesis in platelet transfusion-dependent patients, especially in patients with delayed hematopoietic recovery after transplantation or in the setting of aplastic anemia.

Materials and Methods

Study design and clinical details

All patients were enrolled in Institutional Review Board approved protocols for bone marrow failure or hematologic malignancies and all blood parameters studied were part of the routine clinical care of these patients. Platelet count and IPF were measured on blood drawn into standard EDTA-containing purple top tubes. None of the patients had sepsis, shock or disseminated intravascular coagulation at the time of transfusion, although many were neutropenic and intermittently febrile due to infection. The threshold platelet count for prophylactic platelet transfusion in an otherwise stable patient was 20 × 109/L. Platelets were collected with use of an apheresis device known to yield a leukoreduced platelet concentrate (Amicus Blood Cell Separator, double-needle system, 5.0 liters processed per procedure, Fenwal, Inc., Lake Zurich, IL). All components were irradiated with 2500 cGy (IBL 437C Irradiator, CIS-US, Boston) immediately prior to issue.

Platelet collections for in vitro research use were obtained from three healthy donors enrolled in an IRB-approved study. Apheresis was performed with use of the same device used to collect transfusion products, with the exception that only 4.0 liters were processed per procedure. Each leukoreduced platelet concentrate was split into two bags of equal volume and stored on a platelet agitator at 22°C. Forty-eight hours after collection, one bag from each split collection was irradiated with 2500 cGy. An aliquot of 6 mL was withdrawn from each bag daily to measure platelet count and IPF percent during the 5-day shelf life of the component.

Measurement of IPF and APIN

The immature platelet fraction (IPF) was measured using a Sysmex XE-5000 automated hematology analyzer, with platelet gating accomplished using forward light scatter and identification of immature platelets achieved by staining with polymethine and oxazine fluorescent dyes5 (Sysmex America, Mundelein, IL). These fluorescent dyes penetrate cell membranes and bind to and fluorescently stain RNA, allowing separation of immature (RNA-rich) and mature platelets. IPF is expressed as a percentage, which represents the ratio of immature platelets to the total number of platelets X 100. The AIPN was calculated by multiplying the IPF by the circulating platelet count/100. The reference range for IPF provided by the manufacturer is 0.9 - 11.2%. Testing on a validation sample of 107 healthy subjects in our institution revealed an IPF of 2.6 ± 1.2% (range 0.9 – 7.2%) and AIPN of 6.0 ± 2.7 × 109/L (range 2.4 - 20.7 × 109/L) (values given as mean ± standard deviation).

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired or paired t-tests were used as appropriate to calculate p values between continuous variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD. All statistical studies were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA).

Results

We evaluated the effect of platelet transfusion on the AIPN in 9 platelet transfusion-dependent adult patients with profound hypo-productive thrombocytopenia due to severe aplastic anemia (n=5) or recent high dose chemotherapy given as transplantation conditioning (n=4). The mean pre-transfusion platelet count was 23.3 ± 18.8 × 109/L. One of the transplant recipients was HLA-alloimmunized and received only HLA-compatible platelet components. All patients received single donor leukoreduced platelets collected via apheresis, with a mean component content of 3.09± 0.89 × 1011platelets, a mean volume of 237 ± 72 mL, and mean storage time of 4.1 ± 0.8 days (n=17 components). The platelet increment was 23.2 ± 4.4 × 109/L at one hour following transfusion and 6.2 ± 4.5 × 109/L at one day following transfusion (n=17 transfusion events in 9 patients). All patients had AIPN measured 24 hours or less before platelet transfusion, 15-60 minutes following platelet transfusion, and one day following platelet transfusion.

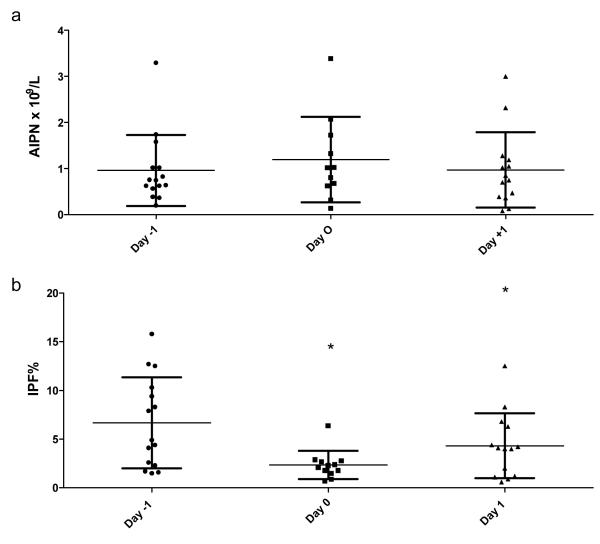

The mean AIPN did not significantly change following platelet transfusion (Figure 1a). In contrast, IPF decreased significantly from 6.6 ± 4.6 % at day -1 to 2.3 ± 1.4% at day 0 before returning to 4.3 ± 2.3% at day +1 (Figure 1b). The absence of changes in the absolute concentration of immature platelets in the peripheral circulation of patients following platelet transfusion, despite significant increases in the circulating platelet counts one hour and one day after transfusion, led us to ask whether the immature platelets presumably present in the circulation of healthy donors and collected by apheresis may be preferentially lost or become undetectable due to RNA degradation during standard storage at room temperature.

Figure 1.

Effect of platelet transfusion on the (a) absolute immature platelet number (AIPN) and (b) Immature Platelet Fraction (IPF) at day -1 (day before transfusion), day 0 (15-60 minutes after transfusion) and day +1 (after transfusion). Each dot represents a single measurement. There are more than 9 points because some patients had these parameters measured before and after multiple platelet transfusions. The horizontal lines indicate the means (graph a, p value 0.74 and graph b, * p < 0.05 as compared with day -1).

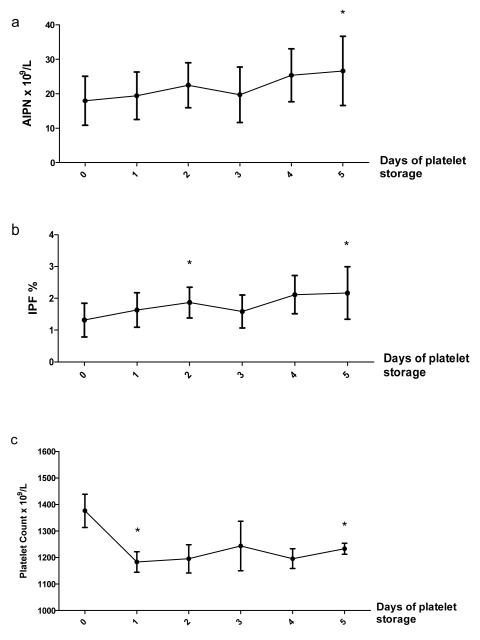

We collected platelets by apheresis from 3 healthy donors and measured the IPF% and calculated the AIPN in the platelet component each day during storage at room temperature. We observed a moderate but statistically significant increase in both AIPN and IPF% over the 5 day period of platelet storage. AIPN increased from 17.9 ± 7.0 × 109/L at day 0 to 26.6 ± 10.0 × 109/L at day 5 (Figure 2a). The IPF% increased from 1.3 ± 0.5 to 2.1 ± 0.8% (Figure 2b) from day 0 to day 5 of storage. In contrast, platelet number in the component decreased during the same period, with a significant drop during the first 24 hours of storage, followed by stabilization over the following 4 days (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Comparison of (a) absolute immature platelet number (AIPN), (b) immature platelet fraction percentage (IPF%) and (c) platelet concentration at different time points from the platelet component during standard storage conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD (* p < 0.05 as compared with day 0).

We also investigated whether irradiation of the platelet components had an impact on immature platelet numbers. The collections were split into two components of equal volume, one of which was exposed to 2400 cGy on the day of collection. Measurements of IPF%, AIPN and platelet counts were performed daily from days 0-5 and were similar in the irradiated and non-irradiated components (data not shown).

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of measurements of the concentration of circulating immature platelets as a predictor of imminent platelet engraftment or recovery following bone marrow transplant or other myelosuppressive therapies.2, 3, 4 The objective of this study was to determine the effects of platelet transfusion on absolute numbers of circulating immature platelets and to document whether transfusion could confound the accurate assessment of marrow platelet production. While staining of platelets with fluorescent RNA dyes was detected in apheresis concentrates immediately after collection, as noted by others,6 the number of fluorescent staining platelets increased over time despite in vitro storage at room temperature. Given that de novo generation of new platelets in vitro, in the platelet component bag, is unlikely, and that degradation of RNA in platelets over time in vitro is expected, the apparent increase in immature platelets detected by this methodology in the apheresis platelet component is likely a staining artifact,6 related in some way to non-specific staining of degrading cells. The fact that there was no increase in AIPN when platelets were transfused indicates that the cells in the component staining with the RNA dyes did not represent functional platelets capable of detection in the circulation following transfusion, since we found no changes in AIPN in the circulation after transfusion in 9 patients. Gamma irradiation of platelet components had no impact on AIPN.

It is also possible that the lack of increase in AIPN in the recipient was due to the dilution effect of transfusing a modest number of immature platelets, on the order of 2% of the total, or 6 × 109 immature platelets in a volume of approximately 200 mL, into an average plasma volume of 3500 mL. Transfusion of a relatively massive number of platelets into a small-stature patient might be reflected in an increase in AIPN. However, this circumstance would be rare in current transfusion practice.

In conclusion, we show that platelet transfusion does not alter the absolute number of circulating immature platelets, and therefore, that assessment of marrow thrombopoiesis using this methodology is possible without regard to the timing of a blood draw relative to platelet transfusions. The AIPN is a reliable marker of marrow production in the presence or absence of platelet transfusion and its predictive role may be of particular importance in patients at risk of graft failure or graft-versus-host disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yu Ying Yau, RN, of the Department of Transfusion Medicine and Sabrina Ivory, Department of Laboratory Medicine, NIH Clinical Center, for their expert assistance in this study.

References

- 1.Briggs C, Kunka S, Hart D, Oguni S, Machin S. J. Assessment of an immature platelet fraction (IPF) in peripheral thrombocytopenia. Brit J Haematol. 2004;126:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggs C, Hart D, Kunka S, Oguni S, Machin S. J. Immature platelet fraction measurement: a future guide to platelet transfusion requirement after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transfus Med. 2006;16:101–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2006.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takami A, Shibayama M, Orito M, Omote M, Okumura H, Yamashita T, Shimadoi S, Yoshida T, Nakao S, Asakura H. Immature platelet fraction for prediction of platelet engraftment after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:501–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barsam SJ, Psaila B, Forestier M, Page LK, Sloane PA, Geyer JT, Villarica GO, Ruisi MM, Gernsheimer TB, Beer JH, Bussel JB. Platelet production and platelet destruction: assessing mechanisms of treatment effect in immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117:5723–5732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walters J, Garrity P. Performance evaluation of the Sysmex XE-2100 Hematology Analyzer. Lab Hematol. 2000;6:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albanyan A, Murphy MF, Wilcock M, Harrison P. Changes in the immature platelet fraction within ageing platelet concentrates. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2213–2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]