Abstract

Objectives

To test the feasibility of delivery and evaluate the helpfulness of a coaching heart failure (HF) home management program for family caregivers.

Background

The few available studies on providing instruction for family caregivers are limited in content for managing HF home care and guidance for program implementation.

Method

This pilot study employed a mixed methods design. The measures of caregiver burden, confidence, and preparedness were compared at baseline and 3 months post-intervention. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize program costs and demographic data. Content analysis research methods were used to evaluate program feasibility and helpfulness.

Results

Caregiver (n=10) burden scores were significantly reduced and raw scores of confidence and preparedness for HF home management improved 3 months after the intervention. Content analyses of nurse and caregiver post-intervention data found caregivers rated the program as helpful and described how they initiated HF management skills based on the program.

Conclusion

The program was feasible to implement. These results suggest the coaching program should be further tested with a larger sample size to evaluate its efficacy.

Introduction

Results of meta-analyses and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines emphasize the critical importance of family caregivers' involvement in home management of heart failure (HF).1,2,3 Family caregivers perform daily HF home management and provide essential support for patients in recognizing worsening symptoms (i.e. edema, shortness of breath).4 Results of several studies have shown that HF rehospitalization is frequently precipitated by excess dietary sodium, inappropriate changes or reductions in taking prescribed medications, and respiratory infections, most of which family caregivers could help prevent if they were educated to be alert for these problems.5,6,7,8 One intervention program found that a family partnership program on HF home care was helpful in adherence to diet with significant reductions in patients' urine sodium.9 Yet, the few available studies on providing instruction for family caregivers are limited in content and lack guidance for implementing HF self-management strategies at home. 10,11,12,13,14 Also, past studies found that 59% or more of family caregivers were employed, and consequently, were not routinely available to attend HF discharge education.15,16

Further, studies consistently report caregivers' lack of knowledge and their need for specific HF home management information, which can prevent rehospitalization.17,18,19 Caregivers can provide support for patients and have greater confidence in HF care when they understand worsening symptoms, are prepared for daily HF management, and experience less emotional burden related to HF caregiving.20,21,22,23 These study results indicate the need for a more effective and targeted family caregiver intervention.

Given the escalating morbidity and mortality of HF and the devastating effects of worsening symptoms, providing caregivers with HF home management information could potentially increase their confidence and skills, and decrease their caregiving burden. Also, in developing interventions that involve family caregivers, researchers need to measure caregiver outcomes (i.e. burden) to ensure that interventions do improve patient outcomes but do not have untoward negative impacts on the caregivers.24

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the feasibility and evaluate the helpfulness and costs of a coaching program for family caregiver HF home care management. The research questions were: (1) Did the family caregivers completing the program and nurse interventionists implementing the coaching program evaluate the program as helpful for HF home management? (2) Were there improvements in outcomes data on caregivers' level of HF caregiving burden, confidence and preparedness in providing HF home care? (3) What were the costs of the program materials and delivery?

Conceptual Framework

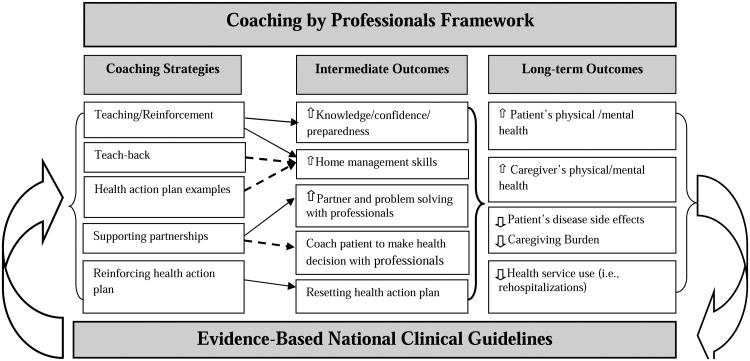

Coaching by healthcare professionals was the framework (Figure 1) used to guide this caregiver HF home care program.25,26 Coaching professionals engage caregivers in specific strategies based on evidence-based national clinical guidelines. The use of nurse coaching strategies (left column) are designed to improve caregiver HF home management skills which can then improve patient and caregiver outcomes27,28 The coaching strategies the nurse uses are the posited behavioral self-efficacy mechanisms29,30 that then increase the intermediate caregiver outcomes (center column) such as knowledge, confidence, preparedness. The combined intermediate outcomes result in the long-term outcomes (right column) such as reduction in caregiving burden improvement in both patient and caregiver health. Coaching strategies provide teaching and reinforcement for resetting home care health action plans.31,32

Figure 1. Coaching Framework for Improving Outcomes in Complex Chronic Care.

Figure 1: Coaching by professionals is an ongoing process (top horizontal box) underscored by using evidence-based national clinical guidelines (bottom horizontal box) for supporting health care self-management and with multiple feedback loops (curved arrows). Solid line arrows represent the published empirically verified relationships bewteen coaching strategies and intermediate outcomes.25,26 The dashed lines indicate the relationships tested in this study. The bold bracket represents the testing of all intermediate outcome data on each of the long-term outcomes in future quantitative studies. Curved arrows illustrate feedback loops linking the coaching by professionals based on national clinical guidelines (left arrow) to long-term outcomes, which link back (right arrow).

The nurse coach teaches the “how-to's” of HF home management such as organizing medication schedules or obtaining tangible resources (i.e., low-cost prescriptions) and providing examples of health action plans (i.e. monitoring fluid retention via daily weighing). The nurse coach also supports partnerships related to patient and caregiver needs for social, financial, or mental health counseling. Further, the nurse coach is an advocate who assists clients in achieving their health action plans within the clients' cultural context or home environment resources. The coach evaluates and subsequently resets the HF home health actions based on each client's performance and progress.25,33 Specifically, coaches use the teach-back mechanisms (caregiver reiterates what they learned) to assess knowledge and skills. Coaching use interactive approaches that engage clients to actively take part in problem solving and decision making about their healthcare. This coaching framework guides intervention development of successful home care management of complex chronic illnesses.34 Thus methods were established to test the telephone coaching caregivers program.

Methods

Research Design

This pilot study employed a mixed methods design. The measures of caregiver burden, confidence, and preparedness were compared pre- and post-intervention. Also overall cost analysis was used to determine the expenses for educational materials and the cost of the nurse's time to administer the coaching program. Focus group and content analysis research methods were used to evaluate the feasibility and helpfulness of the program.

Sample

Caregivers in this study were recruited from a group of HF patients receiving care at a large Midwestern university medical center who were recently hospitalized due to HF exacerbation and who had preserved systolic function or diastolic dysfunction and those with Ejection Fraction < 40%. All patients had received HF information from the same discharge nurse. The inclusion criteria were: (1) family members or significant others (18 years or older) of adult patients with a diagnosis of either systolic or diastolic heart failure (both require similar home care management regimens); (2) alert and oriented individuals who provided written consent to participate and were able to read and write English; and (3) individuals designated by the HF patient as a primary caregiver who assisted the patient on a daily basis. Caregivers of patients who also had Alzheimer's disease were excluded because managing this condition requires different education, coaching, and counseling than that in the HF home management program.

To evaluate the feasibility of the program, we analyzed the proportion of subjects recruited (n=12) compared to those who completed the four-session program (n=10). All 12 family caregivers completed baseline data, and 10 subjects completed the four-session program. Two caregivers completed only the first weekly session (one was too ill and the other was too busy to continue). There was a 12% rescheduling of sessions (5 out of 40) due to conflicts with caregivers' work schedules.

The procedures for the study were approved by the university medical center Institutional Review Board (IRB). All individually identifiable information collected during the study was handled confidentially in accordance with university IRB policies and in compliance with HIPAA regulations. Consent was obtained from caregivers and nurse interventionists as well as from patients for medical record review of demographics data.

Caregiver Telephone HF Home Management Coaching Program

The coaching program for family caregivers was nurse-administered and conducted in four telephone sessions. The content in the program and the need for four coaching sessions was based on previous study results,35,36 the ACC/AHA HF national clinical guidelines1 and the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) information for family and friends,37 also including the HF nurse practitioner input on skills needed by caregivers in daily HF home management activities.36 The content of the four coaching sessions (Table 1) included: (1) preparing the family caregiver for HF home care and reinforcing the plan of care; (2) working with the patient's health care team to develop problem-solving skills to conduct an efficient self-management routine; (3) preventing caregiver strain and burnout and seeking professional help or support groups for caregivers managing in-home HF care; and (4) preparing for caregiver HF challenges and emergency planning.

Table 1. Heart Failure Telephone Coaching Program for Family Caregivers.

| TELEPHONE SESSION | EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES | COACHING ACTIVITIES |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Preparing family caregiver for HF home care and reinforcing the plan of care. |

|

|

| Session 2: Working with the patient's health care team to develop problem-solving skills to conduct an efficient self-management routine. |

|

|

| Session 3: Preventing caregiver strain and burnout and seeking professional help or support groups for caregivers managing in-home HF care. |

|

|

| Session 4: Preparing for caregiver challenges and emergency planning |

|

|

Each family caregiver was given program materials which included two American Heart Association handouts38 and the caregivers' guidebook, The Comfort of Home® for Chronic Heart Failure: A Guide for Caregivers.39 The book and handouts were used during all the telephone sessions. Throughout each session nurses used coaching mechanisms of teaching, providing HF management examples, supporting partnerships with health professionals, and reinforcing use of a daily HF health action plan and problem-solving HF home care challenges. At the end of each telephone coaching session, nurses engaged caregivers in teach-back techniques, asking the caregivers to reiterate what they had learned in that session. 32 Teach-back mechanisms examples included caregivers being asked to explain to the nurse how they would assist in the scheduling of HF medications, monitoring sodium intake in the patient's diet, and helping patients restrict fluid intake (Table 1).

Nurse Interventionist Training and Procedures

For fidelity of the intervention implementation, a 2-hour training session, as well as the materials that would be used in the program was provided to the five nurse interventionists. During the training, each nurse interventionist practiced coaching mechanisms (i.e., reinforce HF medication schedules) and teach-back methods, reviewed the caregiver guide book, and read the selected AHA educational materials to be used during the weekly telephone coaching sessions. Role play was used in the training session. Each nurse was instructed to review all the program materials as well as each of the weekly targeted educational objectives and coaching activities prior to administering the program by telephone. Prompts to coach caregivers by using the mechanisms listed in the left column of Figure 1 were written into the training manual for use in each educational session. Nurses used standard scripts and protocols to guide implementation of the instruction to ensure consistency and fidelity of the coaching program.40,41 Field notes and checklists were used to record the length of intervention administration time, topics discussed, and topics that required reinforcement. In this study, each of the five nurses delivered the complete four-session coaching program to either one, two or three caregivers.

Caregiver Program Outcomes and Cost Measures

Questionnaires were collected at baseline prior to the program and 3 months after completion of the telephone coaching program.

Caregiving burden of HF home care management was measured with a 17-item five-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating more burden or difficulty in providing HF home caregiving. This 17-item scale was modified by Bakas et al based on the original Oberst Caregiving Burden Scale.42 Internal reliability of this 17-item scale has been reported in studies of HF and stroke caregivers, α = .92 and .94 respectively. 43, 44 Examples of items were: “How difficult is it for you to do medical or nursing treatments (e.g. giving medications)?” “How difficult is it for you to manage finances, bills, and forms related to the patient's illness?”

Confidence in providing HF care was assessed by a validated and reliable four-item Likert-type scale (ranging from not confident to extremely confident), with higher scores indicating greater confidence. A sample question was: “Generally, how confident are you that you can help the patient relieve HF symptoms?” The 4-item confidence scale has α=.80.45

Preparedness in providing HF home care was measured in a one-item Likert-type scale (ranging from not at all to very well prepared), with higher scores indicating caregivers felt better prepared. The nationally used, 8-item preparedness scale has high reliability (α=.80-88).46 In this study, we used single item preparedness as recommended by preparedness instrument researchers to reduce questionnaire response burden.47 In our sample, the correlation of the single item to 8-item preparedness was r=.68, p<.001. The single item was: “How well prepared do you think you are now to handle the daily heart failure home care?”

Feasibility and Satisfaction Measures

Caregiver Telephone Interviews

At the end of each telephone session, caregivers were asked, “Were the telephone sessions helpful?” (Prompt: “What did you like best and least about the program?”) “What did you like most and least about the education materials?” “Did you make any changes in your HF self-management behaviors after completing each education session?” (Prompt: “If yes, what were these changes?” “If no, why not?”) Caregivers were also asked if they would like to have had additional tips or information during that coaching session or if any information needed further discussion. This caregiver interview data was categorized using content analysis.

In addition, family caregivers responded to an anonymous telephone “helpfulness” interview administered after completion of all four sessions of the coaching program. Helpfulness data was collected by a nurse who did not provide the coaching program. It was explained to the caregivers that no names would be used, and their responses would be anonymous. The helpfulness rating scale question was: “How helpful was the coaching program to you?” (Options ranged from not helpful, a little bit helpful, somewhat helpful, helpful, and very helpful).

Coaching program cost data was collected for all costs related to implementing the program.48 The cost for nurse time was recorded for delivery of this program. Also, materials and supplies needed to conduct the program were included in the cost analysis. At the end of the coaching program and following the program helpfulness evaluation, caregivers were asked if they would be willing to pay out-of-pocket for the coaching sessions and education materials.

Nurse Interventionist Focus Group

All nurse interventionists shared their experiences in one focus group that was held after delivery of the four-session coaching program. Prior to the focus group, questions were designed to obtain data as to whether nurse interventionists thought the intervention was helpful for caregiver HF home care management, whether nurses had any major challenges in implementing the program, and whether it was feasible to use the program in their current clinical practice setting. During the focus group, the principal investigator took notes and asked probing questions for clarification and depth of information. The focus group discussion was audiotaped, field notes were taken, and data transcriptions were summarized with no individual data source disclosed. The focus group was completed in 90 minutes after data saturation was achieved (no new topics or information was discussed). Both the lead facilitator and the principal investigator were experienced in focus group methods and working with HF patients and caregivers.49 The lead facilitator was a master's-prepared counselor who has conducted focus group discussions in a large clinical trial and had no involvement in developing or conducting this coaching program.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize cost, demographic and HF hospitalization data. Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Ranks test was used to determine whether there was a difference in the caregiving burden scale, preparedness, and the confidence scale responses at baseline and 3 months after the intervention. The Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Ranks test, a non-parametric statistics, is used to determine the magnitude of the differences between groups of paired data when the data do not meet the sample size required for a parametric test.50 Data was analyzed using SPSS version 17.

In this study, content analysis research methods were used to categorize the responses of the five nurse interventionists from the focus group data transcriptions and separately from the caregiver program evaluation narrative data, thus answering the research questions pertaining to the fesibility and helpfulness of the intervention. Content analysis is a method used to identify the presence, meanings and relationships of words or concepts within narrative data.51 A number of steps were taken to maintain trustworthiness and credibility of the data collection and analysis.52 To maintain coding category reliability, all transcriptions were coded independently by two HF content expert researchers who grouped the statements with similar content into distinct categories.53 The quotes from participant's own words were used to develop the common themes. Data saturation was achieved when there was no new topic discussed by the participants. To ensure the consistency of data interpretation, the two researchers met to compare content and resolve the few differences in topic categorization, resulting in subsequent 100% agreement in category themes.54,55 The final categories and themes were reviewed by a HF nurse practitioner. Confidentiality and privacy were safeguarded per HIPAA as transcribed information did not contain participant names or identifiers.

Traditional cost accounting methods were used to calculate caregiving coaching program cost. This traditional method accounts for all expenses related to delivering the program (e.g., personnel time, intervention materials, and telephone expenses) which was averaged per caregiver. 56,57 In this study, nurse interventionist (personnel) cost was calculated by multiplying the time (hours) spent on training and administering the four-session program by the average of the nurse's salary per hour. The cost of the materials and supplies was extracted from the project's expense record. This included a caregiver guide book, printing costs, postage, telephone contacts, paper, and other office supplies used to create and distribute the coaching materials. All costs were tabulated. Although the caregivers received a small honorarium to compensate for their time to participate in this study, this honorarium was not included in this cost analysis. Time developing the program content by a HF nurse practitioner and research questionnaire costs were excluded.

Results

Of the 12 caregivers enrolled in the study (Table 2), 10 reported having one or more chronic health problems (osteoarthritis, hypertension, asthma, myocardial infarction, and diabetes mellitus). One caregiver did not have health insurance coverage. When caregivers were asked to rate the adequacy of family income in relation to paying monthly expenses, two reported having “just enough” money to pay monthly bills and “no more,” while six reported “having enough, with a little extra sometimes.” On the extremes of this rating scale, two reported they “can't make ends meet,” while another two reported “always have money left over.”

Table 2. Sample characteristics of HF patients and their caregivers enrolled in this pilot sudy (n=12).

| Caregiver Characteristics | Percentage/Mean (SD) N (%) | Patient Characteristics | Percentage/Mean (SD) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Age (Years) | 62.6 (13.7) Range=38-81 |

Patient Age | 61.6 (12.8) Range=43-79 |

| Caregiver Gender | Patient Gender | ||

| Female | 9 (75) | Female | 4 (33.3) |

| Male | 3 (25) | Male | 8 (66.7) |

| Employment | Employment | ||

| Full or part time | 3 (25) | Full or part time | 1 (8.3) |

| Retired | 7 (58.3) | Retired | 6 (50) |

| Retired/Disabled | 2 (16.7) | Retired/Disabled | 4 (33.3) |

| Education | Missing (did not answer) | 1 (8.3) | |

| High School | 1 (8.3) | Education | |

| Technical/Some college | 7 (58.3) | High School or lower | 5 (41.7) |

| College or more | 4 (33.3) | Technical/Some college | 6 (50) |

| Race | College or more | 1 (8.3) | |

| Caucasian | 8 (66.7) | Race | |

| African American | 4 (33.3) | Caucasian | 6 (50) |

| Relationship | African American | 5 (41.7) | |

| Spouse | 8 (66.7) | Other | 1 (8.3) |

| Adult child | 1 (8.3) | EF | |

| Mother | 1 (8.3) | < 40 % | 9 (75) |

| Other | 2 (16.7) | ≤ 40 % | 3 (25) |

Patients (Table 2) were predominantly male, eight of them had a diagnosis of HF exacerbation with Ejection Fraction ≤ 40% and another four had preserved systolic function or diastolic dysfunction. All had home caregiving needs. These patients had 2-6 (median=4) comorbidities. All patients ambulated independently at discharge, however one patient required assistance to walk.

Results of the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test indicated that the overall caregiving burden score was lower (M=21.8, SD=8.9) at 3-month follow-up than at baseline (M=25.4, SD=11.8), Z = −1.74, p < .05 (one-tailed). In addition, the descriptive data showed improvement on the twelve caregiving burden items, such as “monitoring patients' progress or worsening symptoms, understanding patients' needs, and coordinating and managing resources for the patient.” The five items on the burden scale that remained unchanged pre and post coaching program were “providing patient personal care, assistance with mobility, managing behavior (moodiness), arranging care while away, and communicating with healthcare professionals.” There was improvement in the total burden score from baseline to 3-month follow-up in all but one caregiver.

Six of 10 caregivers indicated that they had gained more confidence in managing HF at home (from not confident/somewhat confident at baseline to very/extremely confident at 3 months) after the intervention; this includes the four African American caregivers in the sample. Three of the 10 caregivers remained at baseline levels of confident to extremely confident, and one caregiver went from very confident to somewhat confident. Five of the 10 caregivers reported improvement in preparedness scores (from not prepared to well or pretty well prepared) at 3 months after the intervention.

The average length of telephone contact time across the four coaching sessions ranged from 47 minutes to 71 minutes (M=59, SD = +/− 8.1 minutes). Two caregivers went beyond this average time; one took about 106 minutes to complete each session and another took over 100 minutes at the first session, but required less time (average range of 75-90 minutes) in the subsequent sessions. The field notes in these two cases indicated that caregivers revealed concerns and asked questions about end-of-life issues and legal documents, which could account for the additional session time.

Content analysis research methods were used to categorize data from the nurse interventionist focus group and the caregiver interviews into themes (Table 3). Themes that emerged from this data were used to evaluate the feasibility of this study and to answer research questions about the telephone program helpfulness. The content analysis of the caregiver interviews included all caregivers' statements narrative data collected at 3-month follow up telephone interviews.

Table 3.

Themes and Sample Quotes from Intervention Nurses and Caregivers.

| Themes | Nurses' sample quotes | Caregivers' sample quotes |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Use of coaching strategies in delivering the program was valuable to caregivers. The teach-back method determined if caregivers had learned or needed reinforcement. |

“Develop trust” and nurse reinforcing reading food labels, monitor daily weight…” “The teach-back method was valuable because it helps validate whether the caregivers understand the content.” |

Caregivers reiterated: “It is important to keep on top of symptoms, to make and keep doctor appointments.” “I know it is important now to weigh him [patient] every day and write it down.” |

|

2. The program provided caregivers with specific information. Caregivers were able to monitor the patient weight, blood pressure, medication, reportable HF symptoms and their own moods. |

“Caregivers started doing blood pressure measures and monitoring daily weight.” “Caregivers now read food labels for sodium.” “Caregivers comfortable calling doctors and reporting HF symptoms for the patient.” “The advance directive discussion was an eye opener to caregivers.” |

“The diary checklist prompts me to pay more attention to symptoms and needs of the patient.” “I take care of myself. I purposely take time for myself,” “I will talk about an advance directive with the doctor….” |

| 3. Program content and materials were helpful to caregivers. |

“They (caregivers) used the guide book as a reference when they needed more information and shared it with friends and family members.” “Preparing for emergencies was good;” “identifying roles was helpful, especially the roles of the dietitian and social worker.” |

“… The book is our reference. “We have looked several things up, like the AHA diet and caregiver websites.” “Knowing different options and organizations was helpful.” “I know what I'd do in case of emergency…” |

|

4. The coaching program was easily delivered via telephone. Caregivers were comfortable and satisfied with the telephone coaching method. |

“A caregiver told me that having a one-on-one talk with someone who knows [you] by name made a difference.” “Training protocol was helpful, well organized and easy to follow.” |

“I feel sad we have to stop our weekly talks.” “I have my questions answered this week, and I am looking forward to your call next week.” |

| 5. The coaching program could be translated into clinical practice. | “It would be feasible and advantageous to use this coaching technique in clinical practice, but time constraints and cost may pose a challenge.” | This theme was not found in caregivers' telephone interview. |

Four themes that emerged from the caregiver telephone interviews aligned with themes from the intervention nurses' focus group. These themes were: (1) The teach-back mechanism was helpful to determine if caregivers had learned the content and to identify the education needs; (2) Caregivers initiated self-management behaviors (i.e., use of a diary checklist for symptom monitoring, keeping doctors' appointments, or monitoring their own stress); (3) The program and materials were helpful; (4) Caregivers were satisfied with the telephone coaching method. In addition, in the anonymous helpfulness evaluation of the telephone coaching program, all caregivers rated all four coaching sessions as highly satisfactory, and very helpful. All caregivers were willing to pay for coaching sessions and education materials out-of-pocket.

Recorded focus group data from five intervention nurses who conducted the telephone coaching program were grouped by common topics into five major themes. These themes were: (1) The coaching, including teach-back mechanisms were valuable; (2) The program provided specific information caregivers stated they were not familiar with and prompted new self-management skills related to daily HF care; (3) All program content and materials were helpful to caregivers; (4) Coaching was easily delivered via the telephone; and (5) The telephone coaching program could be translated into clinical practice (See Table 3).

Nurse interventionists also agreed that the topics of advanced directives and palliative and end-of-life care should be added to the program. Therefore, a fifth session of telephone coaching should be included after first establishing rapport with the caregiver in order to include these topics and to encourage further discussion with primary healthcare professionals. Nurses described using teach-back methods to help identify specific areas that required reinforcement for specific self-management topics. The most commonly reinforced topics were recording daily weight (in pounds), ways to modify diet and sodium content to stay within the patient's limitations, and stress management. Nurses stated that the telephone coaching program was well received by all family caregivers, and none of the nurses reported having difficulty or challenges delivering the program via the telephone.

The total cost of the program was tabulated. Nurse interventionist time for one caregiver (including telephone scheduling, four session contacts, and a 2-hour training) was: 10 hours × $30 (nurse hourly rate) = $300; the printed information sheets in a notebook = $25 (including shipping and postage); the caregiver guide book = $25. Thus, the total cost = $350 per family caregiver ($87.5 per session).

Discussion

The telephone coaching program was shown to reduce the caregiving burden and improve caregiver confidence and preparedness in HF home care management. As in previous studies, we found that caregivers benefit from HF self-management information.58,59,60

The telephone coaching program was described by the nurses as feasible, helpful, and transferable into practice. Nurses using coaching strategies and teach-back methods in delivering the program resulted in caregivers' use of home-management skills.61 Caregivers not only rated the program as helpful but identified new skills they had gained, likely based on their improved self-efficacy for home HF care.62,63 These findings reflect the feedback loops in the coaching framework, illustrated by the curved arrows in Figure 1. Specifically, the narrative data from both nurses and caregivers indicated that coaching program improved aspects of HF home self-management skills (intermediate outcomes). However, these relationships need to be confirmed with future efficacy studies.

Although the caregivers received all telephone coaching sessions free of charge, their ratings indicated that they were willing to pay for the telephone coaching sessions and the caregiver guide book, even if insurance would not cover this cost. As previously noted, the cost for the program is considerably less than the cost for home health care providers ($120-$160 per each visit), a single emergency department visit, or one inpatient hospitalization for HF due to poor HF home management.64,65 The current emphasis on pay for performance66 and the potential for keeping HF patients out of the hospital support further study of this program.

Limitations

Without a randomized control group, no cause and effect can be established. However, the one group design allows for feasibility testing and for caregivers' and nurse interventionists' evaluation of the program. The sample size was small but included four minority (African American) caregivers who completed all four sessions.

Another limitation of this study was the low participation rate. Twenty eight caregivers of patients recently in the hospital for a HF exacerbation were eligible and invited, 12 participated. Of those not participating, four declined due to deteriorating health of patients or caregivers. The remaining twelve non-participants were too busy or did not respond to the invitation. This 43% (12 out of 28) non-participation rate is likely to improve when program brochures are available prior to patient discharge and nurses, physicians, dieticians, and social workers refer families into the program.

Conclusion

This program was rated helpful by caregivers and feasible to integrate into practice by nurses. Caregivers described how they implemented new HF management skills based on the program. These caregivers had increased confidence and decreased caregiving burden. Likely, self-efficacy related to HF home care management is the mechanism underlying these improvements. The coaching program should be further tested with a larger sample size to evaluate its efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank those nurses who participated in the focus group discussion and family caregivers who participated in the telephone coaching program.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by an award from the American Association of Heart Failure Nurses (AAHFN), Bernard Saperstein Caregiver Grant and partially from, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBl #HL085397s, Ubolrat Piamjariyakul, PhD, RN, awardee). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Association of Heart Failure Nurses or NHLBl.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors have report no conflict of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ubolrat Piamjariyakul, Email: upiamjariyakul@kumc.edu, School of Nursing.

Carol E. Smith, Email: csmith@kumc.edu, School of Nursing, Preventive Medicine and Public Health.

Christy Russell, Email: crussell@mac.md, University of Kansas Medical Center Mid America Cardiology.

Marilyn Werkowitch, Email: mwerkowi@kumc.edu, School of Nursing.

Andrea Elyachar, Email: aelyachar@kumc.edu, School of Preventive Medicine.

References

- 1.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53(15):e1–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):599–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, Appel LJ, Dunbar SB, Grady KL, et al. State of the science: Promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120(12):1141–1163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambardekar AV, Fonarow GC, Hernandez AF, Pan W, Yancy CW, et al. Characteristics and in- hospital outcomes for nonadherent patients with heart failure: Findings from Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) American Heart Journal. 2009;158(4):644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Davis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:80–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forma DE, Butler J, Wang Y, Abraham WT, O'Connor CM, Gottlieb SS, et al. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43(1):61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annema C, Luttik ML, Jaarsma T. Reasons for readmission in heart failure: perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart & Lung. 2009;38(5):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Deaton C, Smith AL, De AK, O'Brien MC. Family education and support interventions in heart failure. Nursing Research. 2005;54(3):158–166. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Heart Association. News Releases: Heart failure patients, caregivers have unmet care needs. 2009 Available at http://americanheart.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=716.

- 11.Clark AM, Freydberg CN, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Armstrong PW, Strain LA. Patient and informal caregivers' knowledge of heart failure: Necessary but insufficient for effective self-care. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2009;11(6):617–621. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Quinn C, Gary RA, Kaslow NJ. Family influences on heart failure self-care and outcomes. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23(3):258–265. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305093.20012.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molloy GJ, Johnston DW, Witham MD. Family caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2005;7(4):592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins LG, Swartz K. Caregiver care. American Family Physician. 2011;83(11):1309–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Alliance of Caregivers. Caregiving in the U.S.: findings from a national survey. 2004 Available at: http://www.caregiving.org/data/04finalreport.pdf.

- 16.Piamjariyakul U, Smith C, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Family Caregivers in Heart Failure (HF): A Pilot Study; International Nursing Conference; Phuket, Thailand. 7-9; Apr, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark AM, Freydberg CN, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Armstrong PW, Strain LA. Patient and informal caregivers' knowledge of heart failure: Necessary but insufficient for effective self-care. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2009;11(6):617–621. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Quinn C, Gary RA, Kaslow NJ. Family influences on heart failure self-care and outcomes. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23(3):258–265. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305093.20012.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molloy GJ, Johnston DW, Witham MD. Family caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2005;7(4):592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duhamel F, Dupis F, Reidy M, Nadon N. A qualitative evaluation of a family nursing intervention. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2007;21(1):43–49. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC. Effect of marital quality on eight-year survival of patients with heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;98(8):1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC, Cranford JA, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM. Beyond the “self” in self efficacy: spouse confidence predicts patient survival following heart failure. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):184–193. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizli I, Chubinski SD, Smith G, Wheeler S, Wu J, et al. Family caregiver outcomes in heart failure. American Journal of Critical Care. 2009;18(2):149–159. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyde M, Turner C, Thompson DR, Stewart S. Educational interventions for patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011;26(4):E27–35. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ee5fb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piamjariyakul U, Reeder KM, Wongpiriyayothar A, Smith CE. Coaching: An Innovative Teaching Strategy in Heart Failure Home Management. In: Henderson JP, Lawrence AD, editors. Teaching Strategy Chapter 7. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wongpiriyayothar A, Piamjariyakul U, Williams PD. Effects of Coaching Using Telephone on Dyspnea and Physical Functioning Among Persons with Chronic Heart Failure. Applied Nursing Research. 2011;24(4):e59–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riegel B, Dickson VV, Hoke L, McMahon JP, Reis BF, Sayer S. A motivational counseling approach to improving heart failure self-care. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21(3):232–241. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelma B, Brawford S, Fleury S, Belyea M. Randomized control trial of the health empowerment intervention. Nursing Research. 2010;59(3):203–211. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbbd4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC, Cranford JA, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM. Beyond the “self” in self efficacy: spouse confidence predicts patient survival following heart failure. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):184–193. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones D, Duffy ME, Flanagan J. Randomized clinical trial testing efficacy of a nurse-coached intervention in arthroscopy patients. Nursing Research. 2011;60(2):92–99. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182002e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith CE, Koehler J, Moore J, Blanchard E, Ellerbeck E. Testing video care education for heart failure. Clinical Nursing Research. 2005;14(2):191–205. doi: 10.1177/1054773804273276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson FL, Baker LM, Nordstrom CK, Legwand CL. Using the teach-back and Orem's self-care deficit nursing theory to increase childhood immunization communication among low-income mothers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2008;31:7–22. doi: 10.1080/01460860701877142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones D, Duffy ME, Flanagan J. Randomized clinical trial testing efficacy of a nurse-coached intervention in arthroscopy patients. Nursing Research. 2011;60(2):92–99. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182002e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes E, McCahon C, Panahi MR, Hamre T, Pohlman K. Alliance not compliance: coaching strategies to improve type 2 diabetes outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part I: Heart failure home management: patients, multidisciplinary healthcare professionals and family caregivers perspectives. Applied Nursing Research. 2011a doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part II: Heart failure home management: integrating patients', professionals', and caregivers recommendations. Applied Nursing Research. 2011b doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) Education Modules on Heart Failure. Module 7: Tips for family and friends. 2006 Available at: http://www.hfsa.org/heart_failure_education_modules.asp.

- 38.AHA (American Heart Association) Getting Healthy. 2010 Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/GettingHealthy_UCM_001078_SubHomePage.jsp.

- 39.Meyer MM, Derr P, Kendall K, Reese J. The Comfort of Home® for Chronic `Heart Failure: A Guide for Caregivers. Portland, Oregon: Cawns LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark AM, Savard LA, Thompson DR. What is the strength of evidence for heart failure disease- management programs? Journal of the American College of cardiology. 2009;54(5):397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zauszniewski JA. Intervention development: assessing critical parameters from the intervention recipient's perspective. Applied Nursing Research. 2010 Aug 3; doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.06.002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberst MT. Unpublished manuscript. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1990. Caregiving burden scale. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakas T, Pressler SJ, Johnson E, Nauser JA, Shaneyfelt T. Family caregiving in heart failure. Nursing Research. 2006;55(3):180–188. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakas T, Austin JK, Jessup SL, Williams LS, Oberst MT. Time and difficulty of tasks provided by family caregivers of stroke survivors. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2004;36(2):95–106. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riegel B, Carlson B, Moser DK, Sebern M, Hicks FD, Roland V. Psychometric testing of the Self- Care of Heart Failure Index. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2004;10(4):350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13(6):375–384. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith CE, Piamjariyakul U, Yadrich SM, Ross VM, Gajewski B, Williams AR. Complex Home Care: Part III-Economic Impact on Family Caregiver Quality of Life and Patient's Clinical Outcomes. Nursing Economic$ 2010;28(6):393–399. 414. PMCID:PMC3075108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong GN, Lairson DR. Cost-effectiveness of alternate contact protocols and cost of mammography promotion interventions for women veterans. Evaluation and Program planning. 2006;29:120–129. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part I: Heart failure home management: patients, multidisciplinary healthcare professionals and family caregivers perspectives. Applied Nursing Research. 2011a doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crichton NJ. Statistical considerations in design and analysis. In: Roe B, Webb C, editors. Research and development in clinical nursing practice. Whurr; London: 1998. p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krippendorf K. Content Analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage: Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(9):1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calloway AK. Qualitative research for development of evidenced-based intervention. Kentucky Nurse. 2005;53(2):7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part I: Heart failure home management: patients, multidisciplinary healthcare professionals and family caregivers perspectives. Applied Nursing Research. 2011a doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Ross VM, Yadrich D, Williams AR, Howard L. Part I: Complex Home Care: Utilization and Costs to Families for Health Care Services Each Year. Nursing Economic$ 2010;28(4):255–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Armstrong GN, Lairson DR. Cost-effectiveness of alternate contact protocols and cost of mammography promotion interventions for women veterans. Evaluation and Program planning. 2006;29:120–129. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wongpiriyayothar A, Piamjariyakul U, Williams PD. Effects of Coaching Using Telephone on Dyspnea and Physical Functioning Among Persons with Chronic Heart Failure. Applied Nursing Research. 2011;24(4):e59–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Ross VM, Yadrich D, Williams AR, Howard L. Part I: Complex Home Care: Utilization and Costs to Families for Health Care Services Each Year. Nursing Economic$ 2010;28(4):255–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Werkowitch M, Elyachar A. Part II: Heart failure home management: integrating patients', professionals', and caregivers recommendations. Applied Nursing Research. 2011b doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.05.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, Coleman EA. Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 2009;25(3):11–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC, Cranford JA, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM. Beyond the “self” in self efficacy: spouse confidence predicts patient survival following heart failure. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):184–193. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones D, Duffy ME, Flanagan J. Randomized clinical trial testing efficacy of a nurse-coached intervention in arthroscopy patients. Nursing Research. 2011;60(2):92–99. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182002e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piamjariyakul U, Smith CE, Ross VM, Yadrich D, Williams AR, Howard L. Part I: Complex Home Care: Utilization and Costs to Families for Health Care Services Each Year. Nursing Economic$ 2010;28(4):255–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moushey L. personal communication. Cost for home health nurse per each home visit 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 66.CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) Reporting hospital quality data for annual payment update. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2010 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/08_HospitalRHQDAPU.asp.