Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the literature to determine if health risk behaviors in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are associated with subsequent symptom burden or level of functioning.

Method

Using the PRISMA systematic review method we searched PubMed, Cochrane, PsychInfo and EMBASE databases with key words: health risk behaviors, diet, obesity, overweight, BMI, smoking, tobacco use, cigarette use, sedentary lifestyle, sedentary behaviors, physical inactivity, activity level, fitness, sitting AND schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, bipolar illness, schizoaffective disorder, severe and persistent mental illness, and psychotic to identify prospective, controlled studies of greater than 6 months duration. Included studies examined associations between sedentary lifestyle, smoking, obesity, physical inactivity and subsequent symptom severity or functional impairment in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Results

Eight of the 2130 articles identified met inclusion criteria and included 508 patients with a health risk behavior and 825 controls. Six studies examined tobacco use and two studies examined weight gain/obesity. Seven studies found that patients with schizophrenia or bipolar illness and at least one health risk behavior had more severe subsequent psychiatric symptoms and/or decreased level of functioning.

Conclusion

Tobacco use and weight gain/obesity may be associated with increased severity of symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder or decreased level of functioning.

Keywords: Health risk behaviors, severe and persistent mental illness, obesity, sedentary behavior

Background

Health risk behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle [1], tobacco use [2], poor diet [3] and obesity [4] have been associated with increased risk of developing chronic medical disorders. These health risk behaviors account for approximately 40% of deaths in the United States [5]. Depression is associated with the incidence of health risk behaviors such as obesity, smoking and lack of exercise potentially causing early development of chronic illnesses such as coronary heart disease (CHD) and diabetes [6]. Once chronic illnesses develop depression is associated with poor self-care including lack of change in diet, increasing exercise, cessation of smoking and taking medications as prescribed [7–9]. In patients with comorbid depression and CHD adverse health risk behaviors have been found to mediate the relationship between depression and morbidity and mortality [8]. Other severe psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder are also associated with a higher prevalence of health risk behaviors and poor self-care (ie adherence to diet, exercise, cessation of smoking and taking medications as prescribed) [10–14]. Thus there is likely a bidirectional relationship between depression and other psychiatric illnesses and chronic medical illnesses [8]. Health risk behaviors may contribute to this bidirectional relationship in patients with depression or severe and persistent mental illnesses (SPMI). For this paper, the term SPMI will refer to only schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

Numerous studies have documented that many chronic illnesses are more prevalent in patients with SPMI compared to the general population [15–19]. For example, Leucht, et al. [15] performed a systematic review and found that cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection and other chronic infectious diseases, hepatitis, osteoporosis, impaired lung functioning, poor dental status, altered pain sensitivity, sexual dysfunction, obstetric complications, thyroid dysfunction, and hyperlipidemia were consistently found to have an increased prevalence in populations of patients with schizophrenia compared to control populations. Notably, many of these disorders, including cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia, are strongly associated with health risk behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle, smoking, poor diet and obesity.

The importance of identification and treatment of health risk behaviors and general medical problems in patients with SPMI has recently been emphasized due to data showing that patients with SPMI are dying of chronic medical illesses one to two decades earlier than community populations [20–29]. A high prevalence of obesity, lack of exercise and tobacco use in patients with SPMI has often been described [13,30,31]. Although these studies call attention to the adverse medical outcomes associated with health risk behaviors, fewer studies have specifically addressed the associations of poor general heath or risk behaviors with the course and symptoms of SPMI.

In this paper, we report the results of a systematic review of the literature assessing whether associations exist between health risk behaviors and the course and symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder measured by standardized measures of symptom severity or functional impairment. Finding an association between health risk behaviors and higher symptom burden or impaired functioning in patients with SPMI could lead to a wider implementation of health risk behavior screening and management in psychiatric clinics.

Methods

We followed the PRISMA method of conducting a systematic review [32], but did not register the review using a pre-specified protocol. We searched the PubMed, Cochrane, PsychInfo and EMBASE databases [last search run on March 30th, 2012] using the following term combinations: health risk behaviors, diet, obesity, overweight, BMI, smoking, tobacco use, cigarette use, sedentary lifestyle, sedentary behaviors, physical inactivity, activity level, fitness, sitting AND schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, bipolar illness, schizoaffective disorder, severe and persistent mental illness, and psychotic to identify reports in English published between January 1980 – March 2012. The reference lists of selected studies were scanned to identify additional articles. Unblinded eligibility assessment was performed by one author (JMC). The search strategy was developed by the authors in consultation with a librarian with expertise in literature searches.

Titles and abstracts of studies returned from the search were screened, and selected full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. We included prospective observational studies or intervention studies of greater than 6 months duration examining as primary or secondary outcomes the associations between health risk behaviors (sedentary lifestyle, smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity) and psychiatric outcomes measured by standardized measures of symptom severity or functional impairment in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder diagnosed by clinical interview, standardized measures or chart review. Included studies were also required to have a control group. Changes in standardized symptom measures or measures of functioning were the principal outcomes.

Information was extracted by one author from each included trial including: patient demographics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, control group, type of study, health risk behaviors studied, outcome measures, effects, and miscellaneous comments. The PRISMA method includes the assessment of risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for intervention studies only [33]. Our review returned only observational studies, so the risk of bias tool was not used.

Results

Study characteristics

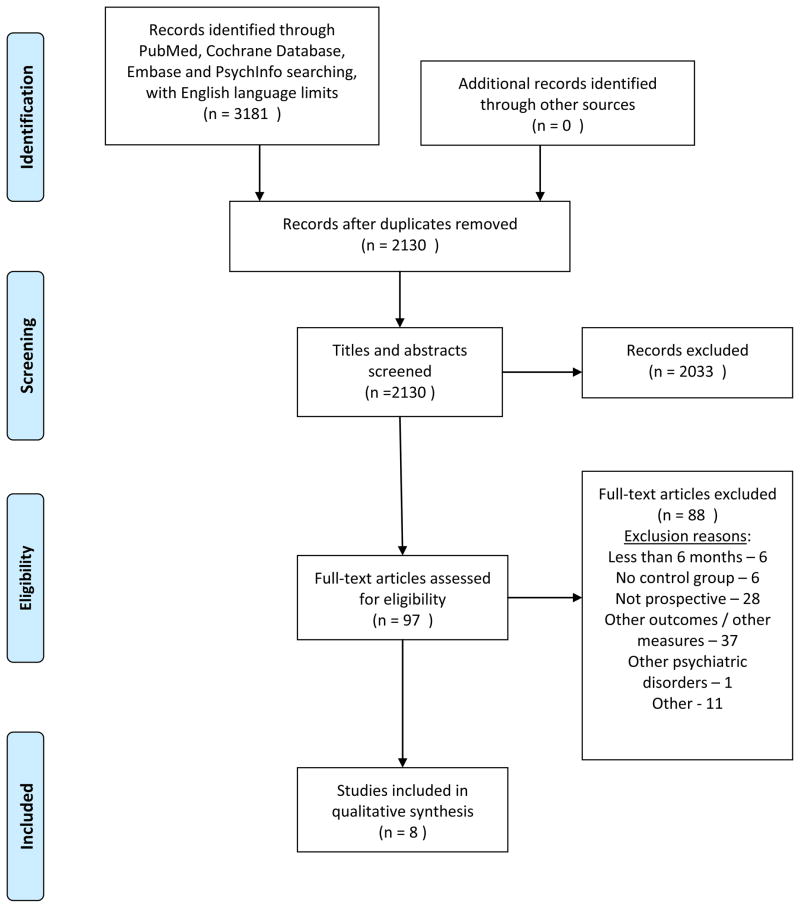

The results of our search are shown in Figure 1. Two thousand one hundred and thirty studies were identified and screened after duplicates were removed. Full articles were pulled and assessed for eligibility for ninety-three of these studies. Eight studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The 8 studies included 508 patients with SPMI and a health risk behavior and 825 control patients with SPMI without a health risk behavior. Study size ranged from 19 to 147 patients and 15 to 322 control patients. Study duration ranged from 9 months to 10 years.

Figure 1.

One study examined the effects of obesity [34], 1 examined effects of weight gain [36] and 6 examined the effects of cigarette use on symptoms of SPMI [35,37–41]. Three studies included patients with bipolar disorder only [34–36], one\ study included those with bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder [37], two included patients with schizophrenia only [38,39], one included patients with first episode psychosis only [40] and one included patients with a first manic or mixed episode only [41]. Two studies [36, 41] included adolescent and adult patients while the rest included only adult patients.

Bipolar disorder

Fagiolini, et al [34] assessed the association of obesity and numerous markers of bipolar disorder severity including time spent in acute episode treatment, time until recurrence of mood episode, and scores on standardized symptom scales. The authors compared 62 patients with bipolar disorder and obesity (defined as BMI >30) to 113 non-obese patients with bipolar disorder prospectively over 2 years. The authors found that obesity was associated with poorer outcomes on all three outcome measures. (See Table for details).

Table 1.

| Study | Patients | Study methods | Control | Health risk behaviors | Outcome measures | Effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fagiolini, et al. (34) | 62 obese patients with bipolar disorder between ages 18–65. | Two year prospective study assessing the effects of patients’ baseline characteristics, including BMI, on the course of bipolar disorder and acute and maintenance treatment outcomes | 113 non-obese patients with bipolar disorder between ages 18–65 | Obesity, defined as body mass index >30 |

|

|

Other health risk behaviors were not assessed |

| Ostacher , et al. (35) | 31 smokers with bipolar disorder with mean age of 37.3 years SD 10.8years | Nine month prospective, longitudinal study of cigarette smoking and suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder | 85 non- smokers with bipolar disorder with mean age of 46.7years SD 13.5 years | Cigarette smoking, defined as any cigarette use in the past month |

|

|

Patients who smoked also had higher rate of lifetime substance abuse (61% vs 33%, p<0.05) |

| Bond, et al. (36) | 19 patients with bipolar disorder 14–35 years old who experienced first manic or mixed episode and >7% increase in body weight in 1 year | One year, prospective naturalistic study of patients with bipolar disorder subsequent to first manic or mixed episode, assessing association of weight gain, bipolar symptoms and functioning | 27 patients with bipolar disorder 14–35 years old who experienced first manic or mixed episode without >7% increase in body weight in 1 year | Weight gain, defined as >7% increase in baseline body weight |

|

|

Differences in functional impairment remained after controlling for mood symptoms, baseline weight and demographics |

| Dodd, et al. (37) | 122 patients with daily cigarette use with bipolar I disorder (n=86) or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n=36) | Two year, prospective, observational study of patients with bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, assessing association of tobacco use and bipolar symptoms | 117 non-daily smoking patients with bipolar I disorder (n=89) or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n=28) (55 patients never smoked, 51 were ex- smokers, 8 were occasional smokers and 3 “experimented a few times” | Smoked tobacco use, defined as daily cigarette use |

|

|

Daily smokers were significantly younger than non-daily smokers (38.17 years +/−10.99 vs 45.67 years +/− 13.26, p<0.0001), and more daily smokers had a history of alcohol dependence (24.6% vs 9.4%, p=0.002) |

| Wang, et al. (38) | 52 patients 18-65 years old with schizophrenia and tobacco use (13.2+/− 8.2 cigarettes/day) , less than 8 weeks after an acute episode | Twelve month long prospective study assessing the association between smoked tobacco use and schizophrenia symptom progression. Some patients were observed up to 26 months | 322 patients with schizophrenia 18–65 years old less than 8 weeks after an acute episode who did not use tobacco | Smoked tobacco use, defined as any cigarette use |

|

|

Sample of smokers with schizophrenia had 45 men and 7 women compared to 127 men and 195 women in nonsmoking group (p<0.001) |

| Kotov, et al. (39) | 147 smokers with schizophrenia who completed the 10 year follow- up | 10 year prospective, observational study evaluating the association between longitudinal symptoms and cigarette consumption | 82 non- smokers with schizophrenia who completed the 10 year follow-up | Smoked tobacco use, defined as any cigarette use over the 30 days preceding assessment at baseline, or over preceding 6 months at follow-up |

|

|

|

| Segarra, et al. (40) | 26 smokers with first episode psychosis 15– 65 years old (8 patients with schizophrenia, 2 with schizoaffective disorder, 4 with bipolar disorder, 12 with other explanations for first episode psychosis | 1 year prospective, observational study evaluating the association between cigarette use, positive and negative symptoms, and cognitive functioning. Included only patients who completed 1 year follow-up. | 15 non- smokers with first episode psychosis 15– 65 years old (5 patients with schizophrenia, 2 with schizoaffective disorder, 1 with bipolar disorder, 7 with other explanations for first episode psychosis | Smoked tobacco use, defined as >/= 15 cigarettes/day |

|

|

|

| Heffner, et al. (41) | 26 adolescent patients (mean age 14.9years +/− 1.6 years) and 23 adult patients (mean age 24.7 years +/−6.7 years) with first episode mania or mixed episode who also smoked cigarettes | 1 year prospective study evaluating the association of tobacco use with symptoms of bipolar disorder and alcohol and cannabis use | 46 non- smoking adolescent patients (mean age 13.9years +/− 1.5 years) and 18 non- smoking adult patients (mean age 26.1 years +/−8.3 years) with first episode mania or mixed episode | Smoked tobacco use defined as self-report of any cigarette use over the month prior to baseline assessment and during the first four months of prospective observation |

|

|

|

Bond, et al [36] prospectively observed the association of weight gain with symptom severity and degree of functioning in 19 patients with bipolar disorder and weight gain (defined as >7% increase in body weight over 1 year) compared to 27 patients with bipolar disorder who did not gain >7% body weight over one year. This trial included patients between ages 14–35 years. Patients with weight gain showed more impairment in functioning, but showed no significant differences in mood symptom or episode relapse outcomes. However, patients with weight gain showed numerically more days with depressive symptoms compared to those without weight gain. Weight gain, level of functioning and mood symptoms were all measured prospectively. Therefore, in this study, it is unclear if weight gain preceded functional impairment and depressive symptoms, or if functional impairment and depressive symptoms preceded weight gain. The authors also noted that it was very likely that this study had limited statistical power to detect an association between weight gain and mood symptoms.

Ostacher, et al [35] studied the association between suicidal behavior and smoking over 9 months in 31 patients with bipolar disorder compared to 85 non-smoking patients with bipolar disorder. Cigarette use was associated with higher scores on measures of suicidality, and patients who smoked made more suicide attempts compared to non-smokers. Patients who smoked also had higher rates of lifetime substance abuse (61% compared to 33%. P<0.05). Although the authors controlled for lifetime substance use using multivariate regression, it is likely that the difference in rates of substance use were proxies for many other differences in the populations that were not controlled for.

Dodd, et al [37] followed 122 patients with tobacco use and either bipolar disorder (n=86) or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n=36) over 2 years and compared several measures of symptom severity compared to non-smoking patients with bipolar disorder (n=89) or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n=28). At 2 years, patients who used tobacco had worse Clinical Global Impression (CGI) – Depression and CGI –Overall Bipolar scores and spent more days hospitalized compared to those who did not smoke. As in the Ostacher, et al [35] study, patients who used tobacco were also more likely to use alcohol. Smoking patients in this study were also significantly younger than non-smoking patients. Multivariate analysis was used to control for age, sex, diagnosis, length of hospitalization, smoking status, medication use over past 24 months, and length of time treated with mood stabilizers, antipsychotics and hypnotics. The analysis did not control for other health risk behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle.

Schizophrenia

Wang, et al [38] examined the rate of cigarette use and associated clinical characteristics in patients with schizophrenia discharged from an acute care hospital living in China. They followed 52 patients who smoked cigarettes and 322 patients who did not smoke for at least 12 months (patients were followed between 12–26 months). The main outcomes were schizophrenia symptom severity measured by standardized scales. Patients who smoked had more hospitalizations than those who did not smoke, and demonstrated less reduction in the hostility-excitement subscore of the PANSS. Otherwise, symptom measures were not significantly different between the two groups. The majority of patients who smoked were men (45 men and 7 women) compared to a mixed population of non-smokers (127 men and 195 women). This study included a multivariate analysis to control for these differences, although other differences that were not controlled for may have been present in the two populations.

Kotov, et al [39] followed patients after first episode psychosis for 10 years and aimed to determine if cigarette use was associated with symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia. Although patients with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder were originally included in this assessment, the study’s main aim was to observe only patients with schizophrenia. One hundred and forty seven smokers with schizophrenia and 82 non-smokers with schizophrenia completed the 10 year observation. The authors used standardized scales as outcome measures. After 10 years, cigarette use was associated with a significant, but modest difference in negative symptom severity as measured by the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and was otherwise not associated with any significant differences in severity of schizophrenia symptoms.

First episode psychosis

One study [40] used neuropsychological assessments to determine the association between cigarette use and cognitive functioning in 41 patients with first-episode psychosis (26 smokers and 15 non-smokers) who completed the 1 year observation. Specific diagnoses were assessed over the 12 months and in both groups the most common diagnosis was schizophrenia. Measures of symptom severity were also performed. The authors found no significant longitudinal differences between the groups in cognitive functioning measured by numerous neuropsychological measures. However, after 12 months, compared to non-smoking controls patients who smoked showed greater increases in total and negative symptoms subscale on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores compared to their baseline scores. Comparisons between patients who did and did not smoke showed no significant differences in symptom severity.

First mixed or manic episode

Heffner et al [41] followed adolescent (n=72) and adult (n=41) patients for 1 year after hospitalization for their first mixed or manic episode to determine the association between cigarette use and bipolar disorder symptom severity measured by time to recovery from first episode, percentage of time with mood symptoms and service utilization outcomes. The authors found no significant differences between those who smoked (n=26 adolescents, n=23 adults) and those who did not smoke (n=46 adolescents, n=18 adults) on any study outcome measure. The only difference between groups was found in the adolescent sub-population where tobacco use was associated with cannabis and alcohol use.

Discussion

Findings and Implications

This systematic review found 8 studies that have prospectively examined the associations among health risk behaviors and symptoms of SPMI. The only health risk behaviors assessed in these studies were weight gain/obesity and tobacco use. No studies have examined other health risk behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle or physical inactivity. Health risk behaviors were associated with adverse outcomes based on either symptoms of SPMI or level of functioning (or both) in 7 out of 8 studies. Outcome measures included duration of episodic symptoms (e.g. time spent in acute treatment, time until recurrence of mood episode), severity of mood and psychotic symptoms (e.g. PANSS, HAM-D), standardized measures of suicidality and functional impairment, and service utilization (e.g. hospitalizations). It remains unanswered whether health risk behaviors are markers of severity of chronic mental illness or whether health risk behaviors influence subsequent symptom severity and functional impairment.

The four studies [34–37] that examined outcomes of patients with bipolar disorder included 198 patients with bipolar disorder and 36 patients with schizoaffective disorder bipolar type plus a health risk behavior. Obesity and weight gain were studied in this population, but not in the population with schizophrenia. The study by Fagiolini, et al [34] suggests that the observed bidirectional relationship between depression and obesity may also be present in bipolar disorder in patients with a BMI > 30. Furthermore, Bond, et al [36] showed that gaining more than 7% body weight over one year is associated with significantly more impairment in functioning after controlling for mood symptoms, even in patients with BMI of less than 30. The authors did not find an association between weight gain and mood symptoms. This study had a small sample size of 19 patients and 27 control patients. Future studies should examine larger populations to assess whether weight gain, obesity or both are associated with worsening symptoms of bipolar disorder or impaired functioning.

Six studies [35,37–41] assessed associations between cigarette use and subsequent symptom severity. Two studies [35,37] were in patients with bipolar disorder, two studies [38,39] in patients with schizophrenia and two in patients with first episode psychosis [40], mania or mixed episode [41]. Only one [45] of these studies did not show an association between cigarette use and poorer outcomes on standardized measures. However, in that study of adolescents and adults with first episode mania or mixed episode, cigarette use was associated with development of cannabis or alcohol use in adolescents [41]. Only one study [40] did not include multivariate analysis in comparing patient populations.

The two studies [38,39] examining outcomes in 199 total patients with schizophrenia who smoked cigarettes found that tobacco use was associated with higher scores on PANSS measurements. The patients in the study by Kotov, et al [39] were followed for 10 years which suggests that the associations observed are stable over time, although the differences between patients who smoked and did not smoke were minor (though significant). The prevalence of tobacco use among patients with schizophrenia is as high as 88% [42], and the most common preventable diseases in the United States are related to smoking [43]. Reducing tobacco use in patients with schizophrenia should have significant health benefits, but may also be associated with reduction in severity of schizophrenia symptoms.

Health risk behaviors associated with SPMI may also lead to early development of chronic medical disorders which may in turn worsen the course of SPMI. However, none of the studies identified in this review examined whether the association of health risk behaviors with subsequent severity of SPMI symptoms is mediated by development or complications from chronic medical disorders. Several authors have suggested ways in which chronic medical disorders may contribute to symptoms of SPMI. Psychiatrists may be less likely to treat schizophrenia in patients with chronic medical disorders [44], the presence of general medical disorders may be associated with prominent depressive and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia [45,46], common pathophysiologic processes may contribute to the general medical problems and the worsening of symptoms of SPMI [47], or general medical disorders may contribute directly to functional impairment in patients with SPMI, which may in turn lead to worsening of the psychiatric disorder [45,48]. Future studies should address the associations among health risk behavior, chronic medical disorders, symptoms of SPMI, and overall level of functioning.

Identifying associations among these behaviors and disorders could lead to a deeper understanding of the premature mortality in patients with SPMI. Long-standing observations of the decreased life expectancy in patients with severe psychiatric disorders have been reconfirmed in newer population based studies and reviews [49–52]. In patients with schizophrenia, some chronic medical problems are also associated with reduced quality of life [53]. These findings have led researchers to develop ways to deliver or coordinate general medical care to this patient population [20]. These new interventions [20,54] have found positive associations between increased access to primary care and improved general health, though the impact on life expectancy remains unknown.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. Although our search strategy yielded 2130 unique articles, only 8 studies fit our inclusion criteria. The small sample size in the majority of studies is a major limitation. Having one adverse health risk behavior is often correlated with a higher likelihood of having multiple health risk behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, use of alcohol and other substances, and lack of use of preventive care [55]. However, most studies did not evaluate and control for a full range of health risk behaviors and quality of medical care received. Using less-stringent inclusion criteria would have increased the number of studies included in our qualitative analysis and increased the total number of patients studied. However, broader inclusion criteria may have also limited the conclusions we could draw from our findings. Our findings are also limited by the databases we searched and the English language restriction. Three studies [35,37,38] also had significant differences in characteristics of patients with the health risk behavior and control populations.

It is notable that all included studies were observational. No studies examined whether an intervention targeting reduction in a health risk behavior (such as increased activity, reduced weight or reduction in cigarette use) was associated with improved outcomes. Positive findings from intervention studies would further strengthen the evidence for an association between health risk behaviors and symptom severity.

Conclusions

We found that 7 out of 8 published prospective studies found negative associations between health risk behaviors and subsequent severity of symptoms of SPMI or decreased level of functioning. No conclusion on the direct impact of health risk behaviors on symptom severity or level of functioning can be made. Large prospective studies are needed that control for socioeconomic variables and a full range of health risk behaviors and quality of medical care. If negative associations between health risk behaviors and SPMI symptoms were consistently shown, then interventions targeting health risk behaviors in patients with SPMI may be associated with reduction in psychiatric disorder symptom severity or improved level of functioning.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: Supported by NRSA grant 5T32MH020021 from the NIMH

Previous presentations of work: No prior presentations

Assistance: The authors wish to acknowledge Judy C. Stribling, MLS, MA for her valuable assistance with the literature search.

Footnotes

Disclaimer statements: Dr. Cerimele has no disclosures. Dr. Katon has received speaking fees from Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Forest during the last 12 months.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joseph M. Cerimele, Email: cerimele@uw.edu, University of Washington School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 1959 NE Pacific St, Box 356560, Seattle, WA 98195, Tel: 206-221-4928, Fax: 206-543-9520.

Wayne J. Katon, Division of Health Services and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 1959 NE Pacific, Dept of Psychiatry, Box 356560, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, 98195.

References

- 1.Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson ME. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1785–1790. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rigotti NA. Treatment of tobacco use and dependence. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:506–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts CK, Barnard RJ. Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:3–30. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00852.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1523–1529. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, et al. Depressive symptoms, health behavios, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2379–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katon W, Richardson L, Russo J, et al. Depressive symptoms in adolescence: the association with multiple health risk behaviors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katon W. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kupfer DJ. The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2528–2530. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmberg SK, Kane C. Health and self-care practices of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(6):827–829. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon L, Postrado L, Delahanty J, Fischer P, Lehman A. The association of medical comorbidity in schizophrenia with poor physical and mental health. J Nerv Ment DIs. 1999;187(8):496–502. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199908000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and obesity, physical inactivity and smoking among a national sample of veterans. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:697–701. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1133–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sokal J, Messias E, Dickerson FB, et al. Comorbidity of medical illnesses among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatry services. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:421–427. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000130135.78017.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber NS, Cowan DN, Millikan AM, Niebuhr DW. Psychiatric and general medical conditions comorbid with schizophrenia in the national hospital discharge survey. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(8):1059–1067. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goff DC, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Druss BG. The mental health/primary care interface in the United States: history, structure and context. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wulsin LR, Sollner W, Pincus HA. Models of integrated care. Med Clin N Am. 2006;90:647–677. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychaitry. 1998;155(12):1775–1777. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer F, Peteet J, Joseph R. Models of care for co-occurring mental and medical disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17:353–360. doi: 10.3109/10673220903463325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thielke S, Vannoy S, Unutzer J. Integrating mental health and primary care. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2007;34:571–592. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MH, Everett A, Kathol R, et al. American Psychiatric Association ad hoc work group report on the integration of psychiatry and primary care [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the health care needs of adults with severe mental illness. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):659–669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Druss BG, Mays RA, Jr, Edwards VJ, Chapman DP. Primary care, public health and mental health. [Accessed March 1st, 2012.];Prev Chronic Dis. 2010 7(1) http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0131.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental illness. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):867–873. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;76(2–3):135–157. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline r results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W-65–W-94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Houck PR, Novick DM, Frank E. Obesity as a correlate of outcome in patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):112–117. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostacher MJ, LeBeau RT, Perlis RH, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with suicidality in bipolar patients. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:766–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bond DJ, Kunz M, Torres IJ, Lam RW, Yatham LN. The association of weight gain with mood symptoms and functional outcomes following a first manic episode: prospective 12-month data from the Systematic Treatment Optimization Program for Early Mania (STOP-EM) Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:616–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodd S, Brnabic AJM, Fitzgerald PB, et al. A prospective study of the impact of smoking on outcomes in bipolar and schizoaffective disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang CY, Xiang YT, Weng YZ, et al. Cigarette smoking in patients with schizophrenia in China: prospective, multicentre study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:456–462. doi: 10.3109/00048670903493348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotov R, Guey LT, Bromet EJ, Schwartz JE. Smoking severity in schizophrenia: diagnostic specificity, symptom correlates, and illness severity. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(1):173–181. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segarra R, Zabala A, Eguiluz JI, et al. Cognitive performance and smoking in first-episode psychosis: the self-medication hypothesis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:241–250. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heffner JL, DelBello MP, Anthenelli RM, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Strakowski SM. Cigarette smoking and its relationship to mood disorder symptoms and co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders following first hospitalization for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00985.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National institute of mental health report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surgeon General’s Reports. The Health Consequences of Smoking. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chwastiak L, Rosenheck R, Leslie D. Impact of medical comorbidity on the quality of schizophrenia pharmacotherapy in a national VA sample. Med Care. 2006;44:55–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000188993.25131.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, Keefe RS, Swartz MS, Leiberman JA. Interrelationships of psychiatric symptom severity, medical comorbidity, and functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(8):1102–1109. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman JI, Wallenstein S, Moshier E, et al. The effects of hypertension and body mass index on cognition in schizophrenia. Am J Psychaitry. 2010;167(10):1232–1239. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasrallah HA. Linkage of cognitive impairment with metabolic disorders in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):1155–1157. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Swartz M, Stroup S, Lieberman JA, Keefe RSE. Relationship of cognition and psychopathology to functional impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):978–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study) Lancet. 2009;374:620–627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chwastiak L, Tek C. The unchanging mortality gap for people with schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:590–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(2):174–156. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lev-Ran S, Le Strat Y, Le Foll B. Impact of hypertension and body mass index on quality of life in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):552–553. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the primary care access, referral, and evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem behavior and psychological development: a longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]