Abstract

Diabetic bladder dysfunction (DBD), a prevalent complication of diabetes mellitus (DM), is characterized by a broad spectrum of symptoms including urinary urgency, frequency, and incontinence. As DBD is commonly diagnosed late, it is important to understand the chronic impact of DM on bladder tissues. While changes in bladder smooth muscle and innervation have been reported in diabetic patients, the impact of DM on the specialized epithelial lining of the urinary bladder, the urothelium (UT), is largely unknown. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis and electron microscopy were used to evaluate UT gene expression and cell morphology 3, 9, and 20 wk following streptozotocin (STZ) induction of DM in female Sprague-Dawley rats compared with age-matched control tissue. Desquamation of superficial (umbrella) cells was noted at 9 wk DM, indicating a possible breach in barrier function. One causative factor may be metabolic burden due to chronic hyperglycemia, suggested by upregulation of the polyol pathway and glucose transport genes in DM UT. While superficial UT repopulation occurred by 20 wk DM, the phenotype was different, with significant upregulation of receptors associated with UT mechanosensation (transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily member 1; TRPV1) and UT autocrine/paracrine signaling (acetylcholine receptors AChR-M2 and -M3, purinergic receptors P2X2 and P2X3). Compromised barrier function and alterations in UT mechanosensitivity and cell signaling could contribute to bladder instability, hyperactivity, and altered bladder sensation by modulating activity of afferent nerve endings, which appose the urothelium. Our results show that DM impacts urothelial homeostasis and may contribute to the underlying mechanisms of DBD.

Keywords: streptozotocin, urothelium, barrier, sensory, diabetic bladder dysfunction

in the united states alone it is estimated that approximately 19 million individuals, comprising both men and women, suffer from diabetes mellitus (DM) (13). DM is characterized by defects in the secretion of the hormone insulin by the pancreas and/or insulin signaling (53), which causes a dysregulation of cellular glucose uptake. Glucose is a large hydrophilic molecule that depends on specific glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins, present on the cell membrane, for cellular entry (12). From the GLUT family (13 cloned to date), GLUT4 is regulated by insulin and controls glucose uptake by skeletal muscle [which accounts for ∼40% of total body mass (70)], cardiac muscle, and adipose tissue (75). Thus Type 1 and 2 diabetics are unable to efficiently transport glucose from the blood into these tissue groups (66) resulting in a state of hyperglycemia. Consequently, glucose inundates cells that express insulin-independent glucose transporters (such as GLUT1). Chronic elevation in cytosolic glucose leads to metabolic abnormalities such as osmotic and oxidative stress, thought to be factors that contribute to tissue injury and dysfunction associated with long-term DM (15, 61).

The urinary bladder is one of the many organs affected by DM. Urine production is increased as hyperglycemia results in elevated glucose filtered load, which when exceeding the reabsorption capacity (renal threshold) of the kidney, leads to osmotic diuresis (63). It is proposed that initially the bladder adapts to polyuria by compensatory, increased activity but subsequently decompensates due to the direct effects of chronic systemic hyperglycemia on bladder tissues (18, 25). DM patients commonly fail to recognize urological symptoms (39) and thus treatment strategies are more likely to be applied at a late stage.

Diabetic cystopathy/diabetic bladder dysfunction (DBD) is a very common DM-associated lower urinary tract pathology, occurring in almost 80% of patients (67). It is a complex, multifactorial disease that affects both storage and emptying/voiding functions and is characterized by a broad spectrum of symptoms including urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia, and incontinence (13, 26). While not considered life threatening, DBD profoundly affects quality of life both from a social and economic perspective. Recent large-scale studies have indicated that patients with DM exhibit a 30–80% increased risk of urinary incontinence (14). There is dispute as to whether this is as a result of compromised bladder voiding ability (overflow incontinence) or a storage problem (urge incontinence) (25, 43, 73).

A number of studies in animal models of DM have shown that morphological and functional manifestations of DBD are time dependent. Bladder hypertrophy and remodeling, increased contractility, and associated neurogenic changes occur soon after the onset of DM (20, 54, 60, 71), while decreased peak voiding pressure, evidenced in urodynamic measurements, develops only at a later stage of DM (23, 25). Alterations in bladder smooth muscle (detrusor) and innervation have also been reported in DM patients (24, 26, 28).

Research to date has focused mainly on detrusor smooth muscle (18), bladder vasculature, and innervation (54), whereas the physiological impact of DM on the epithelial lining of the urinary bladder, the urothelium (UT) (57), is largely unknown. The UT consists of at least three cellular strata: basal, intermediate, and apical/superficial. The highly differentiated cells of the superficial layer, also called umbrella cells, form a vital barrier (44) preventing the flow of toxins, ions, and water between urine and blood (46) as well as protecting the underlying excitable tissues from perturbation by constituents of the urine. The UT expresses a wide range of receptors and produces signaling molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), ATP, and acetylcholine (ACh) (7). Chemical dialogue between the UT and underlying afferent innervation is proposed to play an important role in reflex responses to bladder filling and distension (16). Phenotypic alterations in the UT in pathological conditions such as DM could contribute to bladder dysfunction.

This study explored the temporal impact of DM on UT cell physiology. Relative expression of genes involved in cellular metabolism, cell stress/apoptosis, cell turnover (repair), and sensory reception was assessed in the urothelia of streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats at 3,9, and 20 wk postinduction of DM to examine for progressive urothelial changes in acute versus chronic DM. Findings were statistically compared with age-matched control tissue and correlated with temporal morphological observations. UT ultrastructure was investigated using both transmission (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and relative gene expression was assessed using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR).

METHODS

Animals

All procedures were conducted in accordance with Case Western Reserve University and University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policies. Female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (250–300 g) were used in this study and were fed a standard diet with free access to water.

Induction of Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes was induced after a 24-h fast by a single intraperitoneal injection of 65 mg/kg STZ, diluted in 0.1 M citrate buffer solution, pH 4.5. Three days after STZ treatment, a blood sample was obtained to monitor the blood glucose level. Blood was sampled from the tail vein, and blood glucose levels were measured with Accu-Chek Advantage blood glucose monitoring system. Animals with blood glucose of 300 mg/dl or greater were deemed diabetic and, therefore, suitable for study. Blood glucose was tested before euthanasia, to confirm maintained hyperglycemia (Table 1). The STZ-diabetic animal model can be of substantial value in studying the complications of diabetes and the effect of prolonged hyperglycemia, as STZ-diabetic rats exhibit DBD symptoms similar to those observed clinically in human patients (20, 64). Generation of animal models of disease by genetic manipulation [knockout/overexpression of gene(s)] may result in more global phenotypic changes in the animal's physiology and influence the experimental outcome. The STZ-diabetic rat presents with hyperglycemia due to destruction of pancreatic β-cells, on a normal genetic background.

Table 1.

Plasma glucose

| Blood Glucose, mg/dl | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 wk |

9 wk |

20 wk |

|||

| Control | DM | Control | DM | Control | DM |

| 140.8 ± 5.9 | 440.8 ± 25.2* | 133.1 ± 2.9 | 416.7 ± 17.2* | 129.5 ± 4.1 | 442.9 ± 13.5* |

Values are means ± SE., n = 10. Plasma glucose levels in 3 wk, 9 wk, and 20 wk-diabetes mellitis (DM) rats and age-matched control rats before euthansia.

P < 0.005.

At designated time points of 3, 9, and 20 wk, STZ-diabetic animals and normal rats (n = 10 per group) were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and urinary bladders were dissected and placed in sterile-buffered medium on ice to be processed for electron microscopy (n = 5) and also for dissection of the UT for RNA extraction (n = 5) (gene expression study).

Microscopy

Preparation of samples for TEM.

Excised rat bladders were plunged in EM fixative (2.0% vol/vol glutaraldehyde, 2% wt/vol paraformaldehyde, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 in 100 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4) and incubated for 15 min. Afterwards, the bladder was carefully cut open and then further fixed for 45 min. The tissue was washed with 100 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4, cut into small blocks (2–5 mm in size), and then postfixed in 1.0% wt/vol OsO4, 1.0% wt/vol K4Fe(CN)6, in 100 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4. After a wash with water, the samples were en bloc stained overnight in 0.5% wt/vol uranyl acetate. The tissue were then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and following incubation in propylene oxide, the tissue blocks were embedded in the epoxy resin LX-112 (Ladd; Burlington, VT) and cured 2 days at 60°C. Embedded tissue was sectioned with a diamond knife (Diatome; Fort Washington, PA), and sections, silver to pale gold in color, were mounted on butvar-coated nickel grids, contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed at 80 kV in a JEOL (Japan) 100 CX electron microscope. Images were captured using an L9C Peltier-cooled TEM camera system (Scientific Instruments and Applications, Duluth, GA). Digital images were imported into Adobe Lightroom (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), and the images were processed by using the brightness, contrast, and clarity controls. When contrast was too low, adjustments to the tone curve were made to the whole image. Images were sharpened using a radius of 0.5, and luminance noise reduction was performed. The composite images were assembled using Adobe Illustrator CS5.

Preparation of samples for SEM.

Bladder samples were fixed and osmicated as described for the TEM sample preparation. The tissues were then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, critical point dried, and sputter coated with gold-paladium. Samples were viewed in a JEOL T-300 SEM and samples photographed using an attached Nikon D40 digital camera. The digital images were imported into Adobe Photoshop and contrast and brightness were corrected. The composite images were assembled using Adobe Illustrator CS5.

Molecular Assays

Using a dissecting microscope, excised urinary bladders were carefully cut open to expose the urothelial lining and pinned to a Sylgard-coated dish containing chilled, oxygenated Hank's balanced saline solution (HBSS). The UT was subsequently dissected from the underlying tissue. Samples were homogenized in Lysing Matrix (MP Biomedical) tubes containing TRIzol (Invitrogen) on a FastPrep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedical). The homogenates were then processed for RNA extraction using RNeasy RNA extraction kits (Qiagen), inclusive of a DNase treatment step to eliminate any genomic DNA.

Reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

RNA was measured using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed (RT) with an oligo (dT) primer by Superscript II (Invitrogen). RT controls were performed for each sample by omission of the enzyme. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was conducted using 1.25 units of platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies); primer sequences are listed in Table 2. Amplification products were visualized on a 1.3% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. Purity of the RNA isolation was confirmed by empty RT− lanes. QPCR experiments were then performed using a CFX96 thermal cycler and SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Gene expression was normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) in control and STZ-DM cDNA samples and expressed as fold difference between experimental and control tissue (ΔΔCt) using the Livak Method (55). The data are shown in Fig. 3. Removal of the bladder epithelium by mechanical stripping and processing for mRNA is not likely to include cells of the vasculature, smooth muscle, or neural tissue, though inclusion of a small percentage of other cell types below the basal UT may occur.

Table 2.

Primer pair sequences used in the gene expression study

| Gene | Primer Sequences | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | agcagcagtgagacccctaa | |

| ttccacaggccgatagtagg | NM_031982 | |

| P2X2 | aaacggcactaccaccactc | |

| acgcaccttgtcgaacttct | NM_053656 | |

| P2X3 | aagggaaacctcctgcctaa | |

| cacacccagccgatcttaat | NM_031075 | |

| AChR-M2 | tgcctccgttatgaatctcc | |

| tccacagtcctcacccctac | NM_031016 | |

| AChR-M3 | gtgccatcttgctagccttc | |

| tcacactggcacaagaggag | NM_012527 | |

| SHh | gacccaactccgatgtgttcc | |

| atataaccttgcctgctgttgctg | NM_017221 | |

| Pct1 | acatgttcgctcctgttctggac | |

| gttgagaactcccaagacggtga | NM_053566 | |

| AR | actgccattgcaaaggcatcgtggt | |

| cccccataggactggagttctaagc | NM_012498 | |

| SDH | agacccctcacgacattgcc | |

| attctggctacgaggtcccc | NM_017052 | |

| GLUT1 | cccattcctgtctcttccaa | |

| gagtgtccgtgtcttcagca | NM_138827 | |

| COX2 | agtatcagaaccgcattgcc | |

| taaggtttcagggagaagcg | NM_017232 | |

| BNIP3 | tacctctcagtggtcacttc | |

| gtgggtgtcaatttcagctc | NM_053420 | |

| mTOR | gggcttctgaagatgctgtc | |

| agttcgaagggcaagagtga | NM_019906 | |

| HPRT | atgggaggccatcacattgt | |

| atgtaatccagcaggtcagcaa | NM_012583 | |

| NGF | caaggacgcagctttctatcctg | |

| cttcagggacagagtctccctct | XM_227525 |

Primers were designed using Primer3 software, and melt curves were performed at the end of all QPCR experiments to confirm primer specificity. QPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) was the housekeeping gene. See text for other abbreviations.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE and analyzed using ANOVA followed by unpaired Student's t-test for comparison between temporal groups (test and age-matched controls); a probability level of P ≤ 0.05 was required for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Temporal Changes in Barrier Morphology in DM

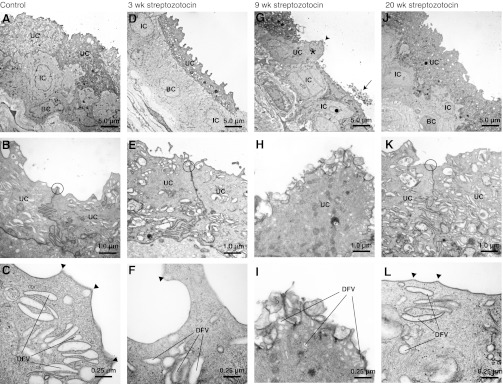

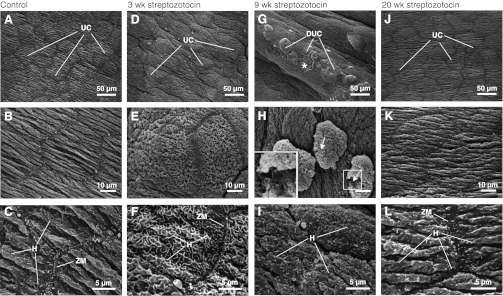

When examined by TEM, the UT of bladders isolated from untreated/control animals was composed of umbrella, intermediate, and basal cell layers (Fig. 1A). A junctional complex (an important intercellular attachment zone) was apparent between adjacent umbrella cells (Fig. 1B), and the apical cytoplasm was replete with discoidal or fusiform-shaped vesicles (DFV) (Fig. 1C). DFV are responsible for delivery of uroplakins (integral membrane proteins important in reducing membrane water permeability) and other proteins to the apical surface of the cells (5, 44). The apical plasma membrane of the umbrella cells was angular in appearance and composed of stereotypical hinge (microplicae) and adjacent plaque regions (Fig. 1C). SEM of the luminal surface of the umbrella cell layer in control tissue revealed a continuous layer of polyhedral-shaped cells (Fig. 2A). The apical surface of the umbrella cells appeared folded into parallel pleats (Fig. 2B), and the border between adjacent cells contained zippered apical membranes (formed by interdigitation of the apical membrane of adjacent cells) (Fig. 2C), which lie just above the tight junctions (47). The angular hinge regions and adjacent plaque regions were visible at higher magnifications (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopic analysis of streptozotocin-treated and control rat bladder urothelium. Rats were untreated (A–C) or 3 wk (D–F), 9 wk (G–I), and 20 wk DM (J–L). The location of the junctional complex between adjacent umbrella cells is circled. In E and F, arrowheads show hinge areas. A, D, G, and J show the three urothelial cell layers: and basel (BC), intermediate (IC), and umbrella (UC). B and C, E and F, H and I, K and L are respectively corresponding stepwise higher magnifications focusing on the umbrella cells. 9 wk DM tissue in G and H and I exhibits dramatic defects in UC morphology, such as fewer discoidal- or fusiform-shaped vesicle (DCV). In G, the asterisk marks an UC that lacks underlying ICs or BCs and has an apical protrusion/dome (marked with an arrowhead). The IC marked with a black dot extends deep into the submucosa. The arrow in G cell debris. J–L from 20 wk DM tissue exhibit normal/unperturbed morphology, similar to A–C from control/untreated tissue and D–F, from 3 wk DM tissue. Images were processed as described in materials and methods.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis of control and streptozotocin (STZ)-treated rat bladder urothelium. SEM was performed to examine the three-dimensional morphology of the surface of the urothelium in control/untreated rats (A–C) or STZ-diabetic rats at 3 wk (D–F), 9 wk (G–I), and 20 wk (J–L) postonset of STZ-induced DM. D–F reveal signs of barrier pathophysiology at 3 wk DM tissue, not apparent in TEM (discussed in the results). G–I show compromised barrier morphology in 9 wk DM tissue. The asterisk in G shows a region where an UC has dissociated, revealing the underlying intermediate cells. The arrows in H indicate regions where the plasma membrane is disrupted. A higher magnification view of the boxed area is shown in the inset. Scale bar is equal to 10 μm. J–L from 20 wk DM tissue show unperturbed/normal morphology of the apical surface of the UCs, similar to A–C, from control/untreated tissue. DUC, dissociating umbrella cell; H, hinge; ZM, zippered apical membrane. Images were processed as described in materials and methods.

Despite the variation in cell shape, which depends on the degree of bladder wall extension at the time of fixation, the general morphology of the UT from 3 wk DM animals appeared similar to that observed in control samples: The three cell layers were present (Fig. 1D), junctional complexes were observed between adjacent umbrella cells (Fig. 1E), DFV were observed in the apical cytoplasm of the umbrella cells (Fig. 1F), and the apical surfaces of the cells were arranged in plaques and hinges. Differences were noted when the surface of the umbrella cells was examined by SEM, which provides a three-dimensional overview of the surface not possible when examining the 70-nm thick TEM sections shown in Fig. 1. When compared with control samples, the 3 wk DM tissue showed a lack of surface pleats (Fig. 2E), and the hinge areas appeared less angular and formed curved ridges that meandered along the apical surfaces of the cells (Fig. 2F). Zippered apical membranes were observed at the border of cell-cell contacts (Fig. 2F).

The most dramatic differences in urothelial morphology were observed in 9 wk DM tissue. While normal-looking epithelium was observed in many sections, ∼20% of sections showed tracks of UT that appeared rugged and disorganized compared with control tissue or tissues after 3 or 20 wk of STZ treatment (compare Fig. 1G with A, D, J). In the latter, the umbrella cell layer sometimes lacked underlying intermediate or basal cells and formed protrusions or domes that extended into the bladder lumen (see umbrella cell marked with an asterisk in Fig. 1G). Domed umbrella cells showed fewer DFVs, and their apical surfaces were covered with membranous blebs and particles (Fig. 1, H–I). Plaques and hinges were vaguely evident in these samples but were less defined than observed in control ones. Furthermore, the boundaries between the intermediate and basal cell layers were less easy to distinguish, and intermediate cells were seen to extend processes deep into the underlying sub mucosa (see dark circle in Fig. 1G). Cell debris was seen to lie above existing cells (e.g., see arrow in Fig. 1G) and necrotic cells, which lacked cytoplasmic density, were sometimes observed between adjacent umbrella cells (data not shown).

SEM findings supported the presence of defective urothelial cells in 9 wk DM tissue, indicating a dramatic breach of the urothelial barrier. Regions of epithelium exhibited broken cell-cell junctions between adjacent cells (Fig. 2G) and in some cases umbrella cell loss, revealing the underlying intermediate cell layer (asterisk in Fig. 2G). In cells that appeared to be detaching from the underlying mucosa, discontinuities were noted in their apical plasma membranes (arrows in Fig. 2H), indicating they were undergoing cell death. The apical surface of the adjacent cells appeared to be covered with disorganized hinges and short protrusions (Fig. 2I).

Evidence of barrier repair was seen in the 20 wk DM tissue. TEM presented a largely reconstituted UT that was morphologically similar to control tissue. It was composed of three cell layers (Fig. 1J), the umbrella cell cytoplasm contained abundant DFVs, and junctional complexes were readily apparent between adjacent cells (Fig. 1K). Furthermore, distinct plaques and hinges were observed at the apical surface of the umbrella cells (Fig. 1L). The apical surface of the umbrella cells was pleated, angular hinges were apparent, and a zippered apical membrane was found at the cell periphery (Fig. 2, J–L).

Temporal Profile of UT Gene Expression in DM

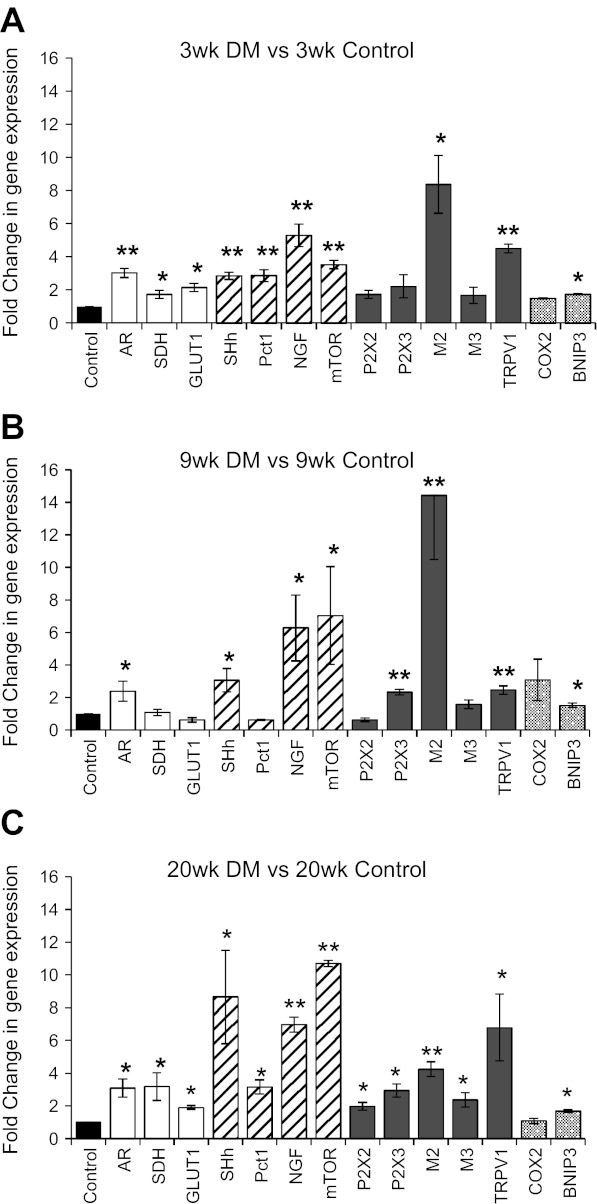

Genes examined for relative transcript (mRNA) expression levels compared with age-matched controls were grouped into the following four categories: glucose metabolism, cell survival and proliferation, cell-signaling receptors, and cell stress and cell death (apoptosis). Data are expressed as fold change in expression of each gene relative to age-matched control for each of the three temporal groups (Fig. 3, A–C).

Fig. 3.

Temporal impact of DM on UT gene expression at: 3 wk (A); 9 wk (B), and 20 wk (C). Genes were grouped into four categories: glucose metabolism (open bars); cell survival and proliferation (hatched bars); cell-signaling receptors (closed bars); cell stress and cell death (apoptosis) (dotted bars). Values are expressed as fold change in gene expression relative to age-matched control values (black bars); n = 4–5; ANOVA, *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.005. See text for abbreviations.

Glucose metabolism.

Temporal expression of the polyol pathway enzymes aldose reductase (AR; converts glucose to sucrose) and sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH; converts sucrose to fructose) (15), and, in addition, glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1; non-insulin-dependent) (4) were examined.

QPCR data indicated significant upregulation of AR at all three time points. SDH and GLUT1 were both significantly elevated at 3 wk and 20 wk DM, whereas 9 wk DM values did not significantly differ from those of age-matched control tissue (Fig. 3, A–C, open bars).

Cell survival and proliferation.

Based on the morphological indication of urothelial repair at 20 wk DM (Fig. 1, J–L; Fig. 2, J–L) following desquamation of the umbrella cell layer noted in 9 wk DM tissue (Fig. 1, G–I; Fig. 2, G–I), we assessed UT temporal expression of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and nerve growth factor (NGF), as these genes are reported to promote cell proliferation (22, 35, 72). As recent evidence supports a dependence of urothelial repair upon signal feedback between basal UT cells, the stromal cells that underlie them, and the sonic hedgehog (SHh) signaling pathway (69), we also examined temporal expression of SHh and its associated receptor patched 1 (Pct1) (40).

QPCR findings showed significant upregulation of NGF, mTOR, and SHh at all three time points compared with age-matched control tissue (Fig. 3, A–C, hatched bars). Pct1 expression exhibited significant increase at the acute 3 wk and late 20 wk DM time points (Fig. 3, A–C, hatched bars); however, at 9 wk DM, values were not significantly different from those of age-matched control tissue (Fig. 3B, hatched bar).

Cell-signaling receptors.

We examined temporal expression of receptors known to be functionally expressed by the UT: purinergic receptors P2X2 and P2X3; cholinergic muscarinic receptors AChR-M2 and AChR-M3; and the transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily member 1 (TRPV1), known to play a role in UT mechanosensation (5).

At the acute 3 wk DM stage, purinergic receptor expression did not differ significantly from age-matched control values (Fig. 3A, closed bars). At 9 wk DM, P2X3 was significantly upregulated while P2X2 was not (Fig. 3B, closed bars). At 20 wk DM, both receptors were upregulated significantly (Fig. 3C, closed bars). AChR-M2 exhibited significantly large increases in expression relative to age-matched control tissue at all time points (Fig. 3, A–C, closed bars), the highest expression was noted at 9 wk DM (Fig. 3B; closed bar). While AChR-M3 did not significantly differ from age-matched control values at 3 wk and 9 wk DM (Fig. 3, A and B, closed bars), it was significantly higher at 20 wk DM (Fig. 3C, closed bars). TRPV1 was significantly upregulated at all three time points (Fig. 3, A–C, closed bars) with its highest expression noted at 20 wk DM.

Cell stress and cell death (apoptosis).

The morphological findings of this study indicated cellular disruption and death within the mucosal lining, predominantly in 9 wk DM tissue (Fig. 1, G–I; Fig. 2, G–I). For this reason, we assessed the temporal expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), classically considered a proinflammatory enzyme induced upon tissue irritation and damage (58), and BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), a gene involved in the apoptotic pathway (29).

Relative to aged-matched control tissue all three time points, BNIP3 expression was significantly higher while COX2 expression was not (Fig. 3, A–C, dotted bars).

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus, a metabolic disorder caused by an absolute or relative deficiency of insulin, is a debilitating and costly disease with multiple serious complications. The most common lower urinary tract complication of DM is diabetic bladder dysfunction. Recent clinical and experimental reports have added storage problems such as urgency and urge incontinence to the traditional description of voiding problems in DBD. The spectrum of bladder dysfunction in patients with type I or type II DM (24) has been ascribed to length of pathology; that is, temporal manifestations may explain the wide variations in DBD symptoms.

Previous functional studies (in vivo: cystometrograms and in vitro: UT-complete detrusor muscle contractility experiments) using STZ-induced diabetic rats and age-matched normal rats over a temporal period extending and including 20 wk DM showed marked differences in bladder function. In the early 3 to 9 wk DM period, increased peak detrusor leak pressure was exhibited and interpreted as a compensatory response to cope with increased urine flow. In the later period, beginning 9 to 12 wk after STZ induction of DM, bladder contractile activity changed (atonic bladder), with peak detrusor leak pressures decreasing and resting bladder pressures increasing (25). This latter finding was noted as potentially due to incomplete bladder emptying resulting in increased postvoid/residual urine.

Very little is known about the temporal impact of DM on the urinary bladder UT, which serves not only as an important urine-blood barrier but also as a dynamic sensory tissue playing an active role in bladder function through chemical dialogue with the underlying excitable bladder tissues (5). The present study was carried out to investigate the temporal profile (over 20 wk) of urothelial morphology and gene expression in STZ-diabetic rats compared with age-matched controls.

Our morphological study of bladder UT includes both SEM and TEM and covers a longer temporal period (20 wk) compared with previous reports of 8 wk [TEM and SEM (38)] and 16 wk [TEM only (65)] post-STZ-induction of DM in rats. Our findings of morphological changes at the acute stage of 3 wk DM (Fig. 2, D–F) progressing to denudation of the mucosal surface at 9 wk DM (Fig. 2, G–I) are similar to those reported by Ibrahim (38). While Rizk et al. (65), using TEM only, do not refer to mucosal denudation, they do report progressive (8 wk, 10 wk, and 16 wk DM) subcellular morphological changes in the UT indicative of pathology and the preapoptotic state. The present temporal study, which extends for a longer time period, revealed that DM is associated with damage to the UT (9 wk DM; Fig. 1, G–I; Fig. 2, G–I) followed by evidence of barrier repair by 20 wk DM (Fig. 1, J–L; Fig. 2, J–L).

Our findings of elevation of polyol-pathway gene expression (AR and SDH) and the non-insulin-dependent glucose transporter GLUT1 in the UT of diabetic rats indicates that this tissue is metabolically impacted by DM-associated hyperglycemia. In addition, elevation in GLUT1 expression and activity is reported to impact directly on polyol-pathway flux by increasing glucose delivery and indirectly, by upregulating expression of AR (12). As the UT is a highly active tissue (with a metabolic rate greater than the detrusor muscle) (37), exposure to elevated glucose levels both on the serosal/blood side and mucosal/urine side in DM, indicates a high potential for metabolic burden. In other non-insulin-dependent tissues such as the retina, lens, and nerves (15, 61), excess cellular influx of glucose is shunted through the polyol- and the pentose-phosphate pathways with detrimental outcomes such as intracellular osmotic stress (mainly due to increased cytoplasmic sorbitol), oxidative stress, intracellular nonenzymatic glycation, and elevated protein kinase C (PKC) activation (62). The lack of increase in SDH at 9 wk DM, in parallel with increased AR expression (Fig. 3b), relative to age-matched control tissue, indicates the potential for intracellular osmotic stress due to accrued cytoplasmic sorbitol and may be a contributing factor in the morphological damage to the UT at this time point (Fig. 1, G–I; Fig. 2, G–I). Although the epithelia of organs such as the intestine regenerate constantly and thus remain continuously proliferative, other organs, such as the mammalian urinary bladder, shift from near quiescence to a highly proliferative state in response to epithelial damage (69). It has recently been reported in the mouse bladder that basal cells of the UT include stem cells capable of regenerating all cell types within the UT and are marked by expression of the secreted protein SHh. In the mouse bladder, regenerative response to urothelial injury has been shown to correlate with increased SHh expression in stem cells within the basal UT layer (69). Our finding of increased expression of SHh (at all 3 time points) and associated receptor Pct1 3 wk and 20 wk DM in DM UT suggest that UT barrier repair in DM very likely involves cells sourced from basal/stem cells of the UT. NGF is not only a target-derived neurotrophic factor, important in the development and maintenance of the peripheral and central nervous systems (49), but it is also reported to have important “epitheliotrophic” (11) effects including epidermal wound healing (56). mTOR is a component of one of three major NGF signaling pathways, the well-established prosurvival pathway: PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (36); it both suppresses apoptosis and promotes cellular growth (17). Studies to date have focused on whole bladder expression of NGF in animal models of DM (45, 67, 74). A temporal decline (9–12 wk post-STZ-DM induction in rat) in whole bladder NGF levels has been proposed to be a permissive/causative factor in DBD by affecting Aδ- and c-fiber bladder afferent pathways (67). As the UT is reported to have abundant expression of both NGF and its receptors (9, 77), we specifically assessed the impact of chronic hyperglycemia on NGF gene expression in this tissue. Our findings show that UT NGF expression is not downregulated in STZ-DM but rather increases (Fig. 3, A–C), with its highest expression noted at the latest time point (Fig. 3C). The increased urothelial expression of NGF in addition to mTOR, seen in the present study, may be supportive of cell survival and proliferative responses contributing to urothelial repair. Upregulation of UT expression may also be due to response of the tissue to denervation (diabetic neuropathy) (32, 33) as bladder nerves lie close to the UT (5).

The UT is a dynamic sensory tissue expressing a wide range of receptors and releasing a large number of transmitters (5). Modification of UT receptor expression in pathological conditions such as DM could result in altered UT signaling during the micturition cycle (especially the bladder-filling stage) (2) and offset the normal chemical dialogue between this tissue and underlying detrusor muscle and sensory afferents (24). In addition, there is strong evidence of important autocrine feedback loops in the UT as these cells express receptors to signaling molecules endogenously released by them, such as ATP (6). AChR-M2 and -M3 are known to be important in detrusor muscle activity during the micturition cycle (68); however, little is known as to the role of these receptors in UT physiology. Increases in expression of UT AChR-M2 and -M3, have been previously reported focusing only on acute (2 wk DM) STZ-diabetic rats (19, 76). Our findings also support significant upregulation in AChR-M2 at the acute stage (3 wk DM; Fig. 3A). Furthermore, we show that AChR-M2 expression is highest at 9 wk DM (Fig. 3B) and remains elevated at the latest (20 wk DM; Fig. 3C) time point. Contrary to previous findings (19) our studies, using real-time QPCR, revealed that AChR-M3 expression was not significantly different at the acute stage (Fig. 3A) and also remained statistically similar to control tissue at 9 wk DM (Fig. 3B). However, at the latest time point of 20 wk DM, AChR-M3 gene expression was significantly elevated (Fig. 3C). In addition to expressing the full complement of muscarinic receptors (48) the UT also expresses enzymes necessary for the synthesis and release of acetylcholine (31, 52). Thus changes in UT expression of AChR-M2 and -M3 receptors in DM may alter UT cholinergic autocrine signaling (31), which could impact on barrier function by modification of tight-junction permeability (59) and also the release of UT ATP (30, 48). The pathophysiological significance of alteration in muscarinic receptor expression in DM will need further investigation.

Urothelial ATP autocrine signaling, mediated by P2X2, P2X3, and possibly P2Y subunits, acts to trigger membrane trafficking to and from the apical membrane of the umbrella cells. In this way, mucosal surface area is reversibly increased to accommodate bladder filling (3, 44). The present findings of upregulated P2X2 gene expression at 20 wk DM (Fig. 3C) and P2X3 gene expression at 9 wk and 20 wk DM (Fig. 3, B and C) may be involved in a chronic augmentation of UT membrane trafficking to accommodate increased urine volumes. In addition to changes in purinergic receptors, TRPV1 transcript has been reported in rodent (8, 27, 79) and human (50) UT, where it is has been proposed to act as a polymodal receptor and play a role in UT mechanosensation (5). Here we report significant elevation in TRPV1 gene expression in the UT of STZ-diabetic rats (Fig. 3, A–C). Contamination of urothelial samples with afferent nerve endings [known to express TRPV1 (2)] is contraindicated by the fact that nerve terminals are unlikely to contain significant amounts of transcript (mRNA). In addition, Daneshgari et al. (54) have reported significantly decreased mucosal/submucosal nerve density by 20 wk in STZ-diabetic rats; a time point in the present study that exhibits the highest expression of this gene (Fig. 3C). Upregulation of UT TRPV1 may lead to hypersensitization of the UT to mechanical stimulation (upon bladder filling) and in turn play a role in augmented reflex transmission (hyper-reflexia), a common symptom of DBD. NGF is reported to increase TRPV1 mRNA expression, mediated in part by the transcription factor Sp1 (21), and may underlie our findings of parallels in expression of both genes in STZ-DM UT. Upregulation of TRPV1 in STZ-DM UT may serve as a cell “braking mechanism” on NGF-proliferative drive, preventing a transition in barrier repopulation/repair activity to one of tumorigenesis (42, 51). In addition, whereas there was no indication of statistically significant changes in the inducible isoform of the cyclooxygenase gene COX2 in STZ-DM UT at all time points examined (Fig. 3, A–C), our finding of COX2 expression in control UT was unexpected. Recent reports of constitutive expression of COX2 in tissues including the brain, kidney, and tracheal epithelial cells, suggest that the biological functions of COX enzymes might be more complex than previously thought (80). Whereas morphological data from this study indicate a normal-appearing UT at the latest time point of 20 wk DM, expression of the pro-apoptotic gene BNIP3 continues to be significantly elevated compared with age-matched control tissue (Fig. 3C). Change in UT cell turnover (growth/death) might impact barrier homeostasis in DM.

The UT normally has a low turnover rate of 3–6 mo (34, 41); however, it rapidly repairs itself within days when damaged (which can occur due to chemical, microbial, or mechanical insult) (44). Based on the molecular findings, the desquamation of the umbrella cell layer by 9 wk DM is very likely associated with metabolic burden due to elevated cellular entry of glucose, and yet the UT regenerates by 20 wk DM in continued presence of hyperglycemia. This apparent adaptation to continued hyperglycemic insult, enabling barrier repair, is accompanied by phenotypic modification of UT receptor expression, which may affect functional responses of the UT and contribute to the symptoms of DBD. In DM, a chronically compromised urothelial barrier would result in open access for entry of toxins, ions, and excreted neurotransmitters such as catecholamines [known to occur in DM (1, 10)], in addition to excreted glucose, to the systemic circulation. Altered UT signaling could have a wide range of effects on UT cell physiology and homeostasis including UT autocrine regulation and chemical dialogue with underlying excitable tissues and contribute to the pathology of DBD.

This initial survey of UT morphology and gene expression following onset of STZ-induced DM will increase our understanding in terms of adaptive responses of the UT to chronic hyperglycemia.

Perspectives and Significance

The UT is not only a vital barrier, protecting bladder tissue from constituents of urine, but is also proposed to play an important role in reflex responses to bladder filling and distension by the release of ATP, which binds to purinergic receptors of sensory nerves endings, communicating the state of bladder fullness to the CNS (16, 78). Our study revealed that chronic hyperglycemia (mimics untreated DM) affects the UT, causing changes in receptor expression and breach to barrier. Phenotypic alterations in the UT, such as alterations in mechanosensitivity or signaling molecule release, could contribute to bladder instability, hyperactivity, and altered bladder sensation and contribute to DBD. Treatment modalities for DBD are limited and as the incidence of DM continues to rise, the importance and medical costs associated with this syndrome are likely to escalate. These findings provide a foundation toward identifying underlying mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of DBD that can provide a basis for new and future approaches to treatment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants K01-DK-080184 (to A. Hanna-Mitchell); R37-DK-054824 and U24-DK-076169 (to L. Birder); U01-DK-61018-02S1 (to F. Daneshgari); R37-DK-54425 and R01-DK-077777 (to G. Apodaca); and by the Urinary Tract Epithelial Imaging Core of the Pittsburgh Center for Kidney Research (P30-DK-079307) and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International Innovative Partnership Grant (19-2006-1061 to F. Daneshgari; co-principal investigator L. Birder).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.T.H.-M., F.D., G.L., and L.A.B. conception and design of research; A.T.H.-M. and G.W.R. performed experiments; A.T.H.-M., G.W.R., and G.A. analyzed data; A.T.H.-M. and G.A. interpreted results of experiments; A.T.H.-M., G.W.R., and G.A. prepared figures; A.T.H.-M. and G.A. drafted manuscript; A.T.H.-M., F.D., G.A., and L.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.T.H.-M., F.D., G.A., and L.A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdel-Aziz MT, Abdel-Kader MM, Rashad MM. Urinary catecholamines and their metabolites in diabetes. Acta Biol Med Ger 710: 1643–1650, 1975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersson KE. Bladder activation: afferent mechanisms. Urology 59: 43–50, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Apodaca G. Modulation of membrane traffic by mechanical stimuli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F179–F190, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Augustin R. The protein family of glucose transport facilitators: It's not only about glucose after all. IUBMB Life 62: 315–333, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Birder LA. Urothelial signaling. Hand Exp Pharmacol 202: 207–231, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Birder LA. Urothelial signaling. Auton Neurosci 153: 33–40, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birder LA, de Groat WC. Mechanisms of disease: involvement of the urothelium in bladder dysfunction. Nat Clin Pract Urol 4: 46–54, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Birder LA, Kanai AJ, de Groat WC, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Burke NE, Dineley KE, Watkins S, Reynolds IJ, Caterina MJ. Vanilloid receptor expression suggests a sensory role for urinary bladder epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13396–13401, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birder LA, Wolf-Johnston AS, Chib MK, Buffington CA, Roppolo JR, Hanna-Mitchell AT. Beyond neurons: involvement of urothelial and glial cells in bladder function. Neurourol Urodyn 29: 88–96, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bolli G, Cartechini MG, Compagnucci P, Malvicini S, De Feo P, Santeusanio F, Angeletti G, Brunetti P. Effect of metabolic control on urinary excretion and plasma levels of catecholamines in diabetics. Horm Metab Res 11: 493–497, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Botchkarev VA, Metz M, Botchkareva NV, Welker P, Lommatzsch M, Renz H, Paus R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin-3, and neurotrophin-4 act as “epitheliotrophins” in murine skin. Lab Invest 79: 557–572, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bouche C, Serdy S, Kahn CR, Goldfine AB. The cellular fate of glucose and its relevance in type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev 25: 807–830, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown JS. Diabetic cystopathy–what does it mean? J Urol 181: 13–14, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown JS, Seeley DG, Fong J, Black DM, Ensrud KE, Grady D. Urinary incontinence in older women: who is at risk? Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Obstet Gynecol 87: 715–721, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burnstock G. Purine-mediated signalling in pain and visceral perception. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22: 182–188, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cao GF, Liu Y, Yang W, Wan J, Yao J, Wan Y, Jiang Q. Rapamycin sensitive mTOR activation mediates nerve growth factor (NGF) induced cell migration and pro-survival effects against hydrogen peroxide in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414: 499–505, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Changolkar AK, Hypolite JA, Disanto M, Oates PJ, Wein AJ, Chacko S. Diabetes induced decrease in detrusor smooth muscle force is associated with oxidative stress and overactivity of aldose reductase. J Urol 173: 309–313, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng JT, Yu BC, Tong YC. Changes of M3-muscarinic receptor protein and mRNA expressions in the bladder urothelium and muscle layer of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett 423: 1–5, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Christ GJ, Hsieh Y, Zhao W, Schenk G, Venkateswarlu K, Wang HZ, Tar MT, Melman A. Effects of streptozotocin-induced diabetes on bladder and erectile (dys)function in the same rat in vivo. BJU Int 97: 1076–1082, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chu C, Zavala K, Fahimi A, Lee J, Xue Q, Eilers H, Schumacher MA. Transcription factors Sp1 and Sp4 regulate TRPV1 gene expression in rat sensory neurons. Mol Pain 7: 44, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Costa MM, Violato NM, Taboga SR, Goes RM, Bosqueiro JR. Reduction of insulin signalling pathway IRS-1/IRS-2/AKT/mTOR and decrease of epithelial cell proliferation in the prostate of glucocorticoid-treated rats. Int J Exp Pathol 93: 188–195, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daneshgari F, Huang X, Liu G, Bena J, Saffore L, Powell CT. Temporal differences in bladder dysfunction caused by diabetes, diuresis, and treated diabetes in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1728–R1735, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Daneshgari F, Liu G, Birder L, Hanna-Mitchell AT, Chacko S. Diabetic bladder dysfunction: current translational knowledge. J Urol 182: S18–S26, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daneshgari F, Liu G, Imrey PB. Time dependent changes in diabetic cystopathy in rats include compensated and decompensated bladder function. J Urol 176: 380–386, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daneshgari F, Moore C. Diabetic uropathy. Semin Nephrol 26: 182–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Everaerts W, Vriens J, Owsianik G, Appendino G, Voets T, De Ridder D, Nilius B. Functional characterization of transient receptor potential channels in mouse urothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F692–F701, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faerman I, Glocer L, Celener D, Jadzinsky M, Fox D, Maler M, Alvarez E. Autonomic nervous system and diabetes. Histological and histochemical study of the autonomic nerve fibers of the urinary bladder in diabetic patients. Diabetes 22: 225–237, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feng X, Liu X, Zhang W, Xiao W. p53 directly suppresses BNIP3 expression to protect against hypoxia-induced cell death. EMBO J 30: 3397–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanna-Mitchell A, de Groat W, Kanai A, Levitan E, Birder L. The correlation of vesicular traffic and transmitter release in bladder urothelial cells: involvement of urothelial muscarinic receptors and overactive bladder (Abstract). Neurourol Urodyn 26: 689–690, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hanna-Mitchell AT, Beckel JM, Barbadora S, Kanai AJ, de GWC, Birder LA. Non-neuronal acetylcholine and urinary bladder urothelium. Life Sci 80: 2298–2302, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hellweg R, Hartung HD. Endogenous levels of nerve growth factor (NGF) are altered in experimental diabetes mellitus: a possible role for NGF in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. J Neurosci Res 26: 258–267, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heumann R, Korsching S, Bandtlow C, Thoenen H. Changes of nerve growth factor synthesis in nonneuronal cells in response to sciatic nerve transection. J Cell Biol 104: 1623–1631, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hicks RM. The mammalian urinary bladder: an accommodating organ. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 50: 215–246, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hong J, Qian T, Le Q, Sun X, Wu J, Chen J, Yu X, Xu J. NGF promotes cell cycle progression by regulating D-type cyclins via PI3K/Akt and MAPK/Erk activation in human corneal epithelial cells. Mol Vis 18: 758–764, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 609–642, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hypolite JA, Longhurst PA, Gong C, Briscoe J, Wein AJ, Levin RM. Metabolic studies on rabbit bladder smooth muscle and mucosa. Mol Cell Biochem 125: 35–42, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ibrahim SH. Evaluation of time-dependent structural changes of rat urinary bladder in experimentally-induced diabetes mellitus light and electron microscopic study. Egypt J Urol 30: 367–382, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ioanid CP, Noica N, Pop T. Incidence and diagnostic aspects of the bladder disorders in diabetics. Eur Urol 7: 211–214, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jenkins D. Hedgehog signalling: emerging evidence for non-canonical pathways. Cell Signal 21: 1023–1034, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jost SP. Cell cycle of normal bladder urothelium in developing and adult mice. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 57: 27–36, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalogris C, Caprodossi S, Amantini C, Lambertucci F, Nabissi M, Morelli MB, Farfariello V, Filosa A, Emiliozzi MC, Mammana G, Santoni G. Expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) in urothelial cancers of human bladder: relation to clinicopathological and molecular parameters. Histopathology 57: 744–752, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaplan SA, Te AE, Blaivas JG. Urodynamic findings in patients with diabetic cystopathy. J Urol 153: 342–344, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khandelwal P, Abraham SN, Apodaca G. Cell biology and physiology of the uroepithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1477–F1501, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koo HP, Santarosa RP, Buttyan R, Shabsigh R, Olsson CA, Kaplan SA. Early molecular changes associated with streptozotocin-induced diabetic bladder hypertrophy in the rat. Urol Res 21: 375–381, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kreft ME, Hudoklin S, Jezernik K, Romih R. Formation and maintenance of blood-urine barrier in urothelium. Protoplasma 246: 3–14, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kreplak L, Wang H, Aebi U, Kong XP. Atomic force microscopy of mammalian urothelial surface. J Mol Biol 374: 365–373, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kullmann FA, Artim D, Beckel J, Barrick S, de Groat WC, Birder LA. Heterogeneity of muscarinic receptor-mediated Ca2+ responses in cultured urothelial cells from rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F971–F981, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science 237: 1154–1162, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li M, Sun Y, Simard JM, Chai TC. Increased transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) signaling in idiopathic overactive bladder urothelial cells. Neurourol Urodyn 30: 606–611, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li S, Bode AM, Zhu F, Liu K, Zhang J, Kim MO, Reddy K, Zykova T, Ma WY, Carper AL, Langfald AK, Dong Z. TRPV1-antagonist AMG9810 promotes mouse skin tumorigenesis through EGFR/Akt signaling. Carcinogenesis 32: 779–785, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lips KS, Wunsch J, Zarghooni S, Bschleipfer T, Schukowski K, Weidner W, Wessler I, Schwantes U, Koepsell H, Kummer W. Acetylcholine and molecular components of its synthesis and release machinery in the urothelium. Eur Urol 51: 1042–1053, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu G, Daneshgari F. Temporal diabetes- and diuresis-induced remodeling of the urinary bladder in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R837–R843, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu G, Li M, Vasanji A, Daneshgari F. Temporal diabetes and diuresis-induced alteration of nerves and vasculature of the urinary bladder in the rat. BJU Int 107: 1988–1993, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-Delta Delta C(T)] Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Matsuda H, Koyama H, Sato H, Sawada J, Itakura A, Tanaka A, Matsumoto M, Konno K, Ushio H, Matsuda K. Role of nerve growth factor in cutaneous wound healing: accelerating effects in normal and healing-impaired diabetic mice. J Exp Med 187: 297–306, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Melicow MM. The urothelium: a battleground for oncogenesis. J Urol 120: 43–47, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Neufang G, Furstenberger G, Heidt M, Marks F, Muller-Decker K. Abnormal differentiation of epidermis in transgenic mice constitutively expressing cyclooxygenase-2 in skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7629–7634, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Phillips TE, Phillips TL, Neutra MR. Macromolecules can pass through occluding junctions of rat ileal epithelium during cholinergic stimulation. Cell Tissue Res 247: 547–554, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pitre DA, Ma T, Wallace LJ, Bauer JA. Time-dependent urinary bladder remodeling in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model. Acta Diabetol 39: 23–27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase mediates cytotoxic signals of hyperglycemia and TNF-alpha in human lens epithelial cells. FASEB J 17: 315–317, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ramasamy R, Goldberg IJ. Aldose reductase and cardiovascular diseases, creating human-like diabetic complications in an experimental model. Circ Res 106: 1449–1458, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rave K, Nosek L, Posner J, Heise T, Roggen K, van Hoogdalem EJ. Renal glucose excretion as a function of blood glucose concentration in subjects with type 2 diabetes–results of a hyperglycaemic glucose clamp study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2166–2171, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rees DA, Alcolado JC. Animal models of diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 22: 359–370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rizk DE, Padmanabhan RK, Tariq S, Shafiullah M, Ahmed I. Ultra-structural morphological abnormalities of the urinary bladder in streptozotocin-induced diabetic female rats. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 17: 143–154, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414: 799–806, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sasaki K, Chancellor MB, Phelan MW, Yokoyama T, Fraser MO, Seki S, Kubo K, Kumon H, Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Diabetic cystopathy correlates with a long-term decrease in nerve growth factor levels in the bladder and lumbosacral dorsal root Ganglia. J Urol 168: 1259–1264, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sellers DJ, Chess-Williams R. Muscarinic agonists and antagonists: effects on the urinary bladder. Hand Exp Pharmacol 208: 375–400, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shin K, Lee J, Guo N, Kim J, Lim A, Qu L, Mysorekar IU, Beachy PA. Hedgehog/Wnt feedback supports regenerative proliferation of epithelial stem cells in bladder. Nature 472: 110–114, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Smith AG, Muscat GE. Skeletal muscle and nuclear hormone receptors: implications for cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2047–2063, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sonar SS, Ehmke M, Marsh LM, Dietze J, Dudda JC, Conrad ML, Renz H, Nockher WA. Clara cells drive eosinophil accumulation in allergic asthma. Eur Respir J 39: 429–438, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sonar SS, Schwinge D, Kilic A, Yildirim AO, Conrad ML, Seidler K, Muller B, Renz H, Nockher WA. Nerve growth factor enhances Clara cell proliferation after lung injury. Eur Respir J 36: 105–115, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Starer P, Libow L. Cystometric evaluation of bladder dysfunction in elderly diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 150: 810–813, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Steinbacher BC, Jr, Nadelhaft I. Increased levels of nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder and hypertrophy of dorsal root ganglion neurons in the diabetic rat. Brain Res 782: 255–260, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stockli J, Fazakerley DJ, Coster AC, Holman GD, James DE. Muscling in on GLUT4 kinetics. Commun Integr Biol 3: 260–262, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tong YC, Cheng JT. Alterations of M2,3-muscarinic receptor protein and mRNA expression in the bladder of the fructose fed obese rat. J Urol 178: 1537–1542, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vizzard MA. Changes in urinary bladder neurotrophic factor mRNA and NGF protein following urinary bladder dysfunction. Exp Neurol 161: 273–284, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vlaskovska M, Kasakov L, Rong W, Bodin P, Bardini M, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G. P2X3 knock-out mice reveal a major sensory role for urothelially released ATP. J Neurosci 21: 5670–5677, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yu W, Hill WG, Apodaca G, Zeidel ML. Expression and distribution of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in bladder epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F49–F59, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zimmermann KC, Sarbia M, Schror K, Weber AA. Constitutive cyclooxygenase-2 expression in healthy human and rabbit gastric mucosa. Mol Pharmacol 54: 536–540, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]