Abstract

Background

In clinical trials, 5FU/oxaliplatin improves survival in resected stage III colon cancer with manageable toxicity. This combination’s tolerability in the general population of colon cancer patients is uncertain.

Methods

Adverse outcomes were compared in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with 5FU or 5FU/oxaliplatin within 120 days of resection and a control group of stage II patients not treated with chemotherapy in SEER-Medicare and New York State Cancer Registry linked to Medicare and Medicaid. Hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient adverse events (AEs) were measured in claims from 30 days-9 months after resection. Multiple logistic regressions calculated adjusted odds ratios of events by treatment. Propensity score matching was used to minimize selection bias.

Results

Adverse outcomes were more frequent for chemotherapy recipients. AE rates were higher in 5FU/oxaliplatin treated as compared to 5FU-only treated patients, e.g. 81% versus 72% respectively in SEER-Medicare. Oxaliplatin’s effect on AE was greater in older patients, SEER-Medicare OR ≥75 2.10, 95% CI 1.53-2.87 vs. <75 1.75, 95% CI 1.39-2.21. ER use was high in Medicaid patients (83% of chemotherapy-treated), but neither ER use nor hospitalization was increased by oxaliplatin. 60-day mortality was 1-3% in 5FU patients and 1-2% in 5FU/oxaliplatin patients.

Conclusions

The incremental harms of 5FU/oxaliplatin compared with 5FU-only adjuvant chemotherapy are modest in patients with stage III colon cancer insured by Medicare and Medicaid. The additional harms in patients ≥75 are largely restricted to outpatient events and do not extend to an increased rate of hospitalization or early death.

Keywords: colon cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy, toxicity, elderly, oxaliplatin

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States.1 For patients with stage III (lymph node-positive) colon cancer, six months of post-surgical adjuvant chemotherapy with leucovorin-modulated 5-fluorouracil (5FU) was the standard of care from 1990 to 2004 based on clinical trials demonstrating a 25% relative reduction in mortality over surgery alone.2, 3 Since 2004 the combination of 5FU and oxaliplatin has been standard based on a 20% further reduction in mortality offered by the addition of oxaliplatin.4

Although the addition of oxaliplatin to adjuvant therapy improves survival, it also increases toxicity. In the pivotal Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer (MOSAIC) trial, oxaliplatin increased severe paresthesias by 12%; increased severe neutropenia by 37%; and increased severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea by 3 to 4% each.5 Less severe toxicities were increased more profoundly. Little is known about the severity of oxaliplatin toxicity in patients treated in the community who are older and less healthy than clinical trial populations.6, 7 Moreover, although drug dosing and supportive care are well-defined in trials, off-trial patients may face varying dosing and supportive care practices that could alter the tolerability of oxaliplatin.

In 2010, Kahn et al reported on the toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy for the stage III colon cancer patients in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) study, a cohort of newly diagnosed patients from diverse treatment settings.8 Among 574 patients with stage III colon cancer who received chemotherapy in CanCORS, adverse events between 31 days and 15 months after surgical resection were higher in patients who received oxaliplatin; however, after excluding neuropathy, patients who received oxaliplatin did not experience more adverse events in any age group. However, in light of the known increase in toxicity from oxaliplatin seen in clinical trials and because only 14 patients aged ≥75 in CanCORS received oxaliplatin, the true incremental toxicity of oxaliplatin in the community in general, and in patients aged >75 years in particular, remains unmeasured.

The primary objective of the current study was to examine whether oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy regimens result in measurable differences in toxicity experienced by patients treated in the context of usual care. Data from 3 observational cohorts were used to compare hospitalization, emergency department (ER) use, and billing for common adverse events (AEs) between patients who received oxaliplatin/5FU and patients who received 5FU in the community.

METHODS

Data Sources

Cohorts for this study were derived from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare), the New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) linked to Medicaid claims; and NYSCR linked to Medicare claims. The NCI links data on incident cancers from the SEER program of cancer registries to patients’ corresponding fee-for-service Medicare claims allowing longitudinal assessment of treatment and outcomes.9, 10 SEER-Medicare data in years 2003 to 2007 were included. The NYSCR-linked Medicare and Medicaid data (years 2002-2006) fundamentally are similar, with NYSCR data linked to administrative claims data beneficiaries of these public insurance programs. The Institutional Review Board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute approved this study (IRB 08-338).

Sample Eligibility and Treatment Ascertainment

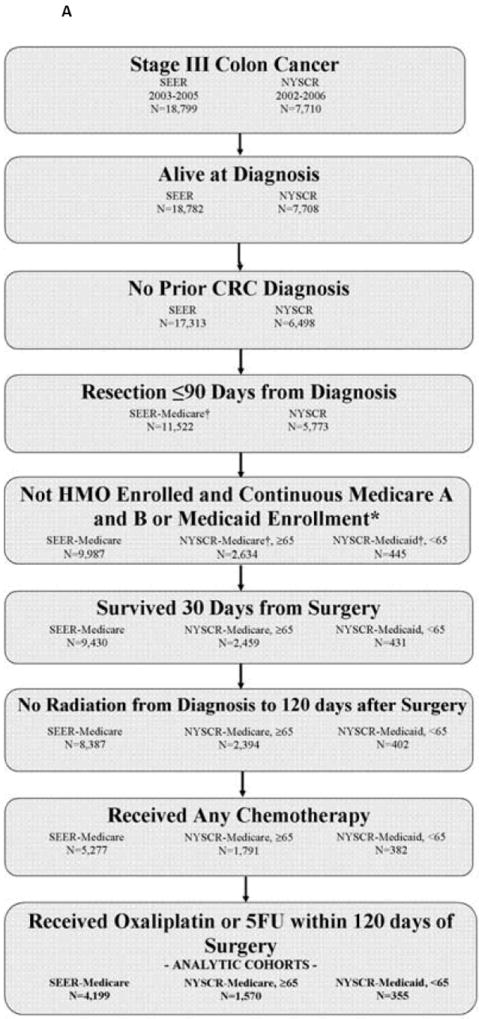

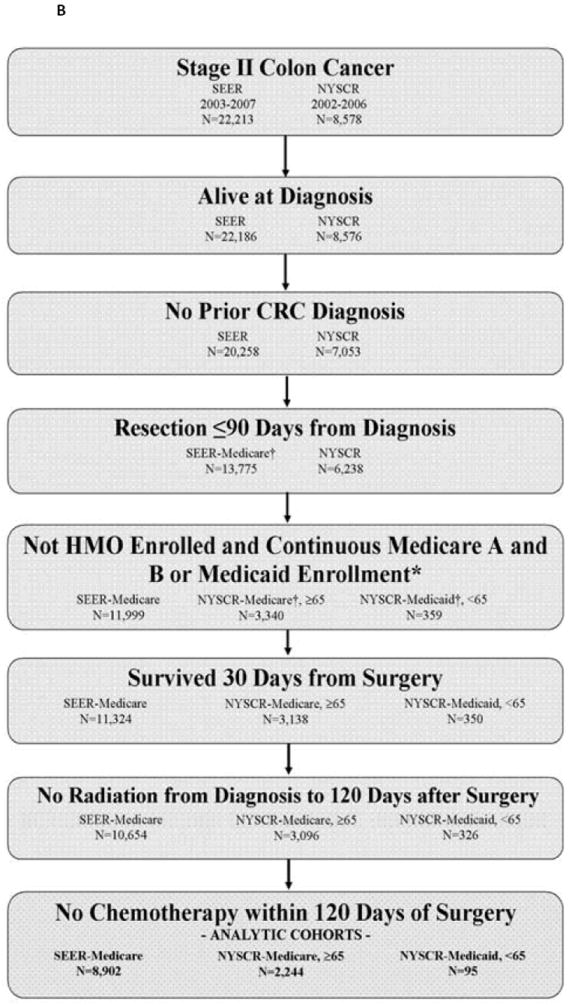

To assure complete capture of claims data, Medicare patients were excluded if they were enrolled in a Medicare Managed Care/health maintenance organization (HMO) or if they were not continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B in the 12 months after diagnosis. Medicaid patients were excluded if not continuously enrolled in Medicaid in the 12 months after diagnosis. To facilitate interpretation of dual Medicare-eligible and Medicaid-eligible patients, NYSCR-Medicare is restricted to patients 65≥years, including dual-eligible patients; NYSCR-Medicaid is restricted to patients < 65 years, including dual-eligible patients. Eligible patients had newly diagnosed, stage III adenocarcinoma of the colon (excluding the rectum) that was resected within 90 days of diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they died within 30 days of surgery or if they received radiation therapy from time of diagnosis to 120 days after surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A: Stage III Cohort Assembly

B: Stage II Cohort Assembly

† Registry-claims files linked here.

* Enrollment restrictions applied to the 12 months following diagnosis. HMO restriction applied to Medicare patients only.

Patients without a chemotherapy claim within 120 days of surgery comprised a no-chemotherapy group. Patients who had a chemotherapy claim within 120 days were assigned to the 5FU/oxaliplatin group if they had an oxaliplatin claim within 30 days of starting chemotherapy. Patients were assigned to the 5FU group if they had any 5FU or capecitabine claim and no claim for oxaliplatin, irinotecan, cetuximab, or bevacizumab within 30 days of starting chemotherapy. Patients receiving chemotherapy regimens that did not fall into either of these two categories were excluded.

Because the intent of the study was to compare adverse chemotherapy outcomes, a control group of patients with resected stage II colon cancer was included to provide an estimate of the baseline rate of events expected from a similar group of patients with surgically resected colon cancer who did not receive chemotherapy. Patients with untreated stage II disease were chosen as a comparison group because adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer is optional in light of the small absolute benefit provided. In contrast, chemotherapy is standard for stage III colon cancers; therefore, patients with untreated stage III disease inevitably are different, presumably sicker, than treated patients. The stage II control group met eligibility criteria defined above, but had no claims for chemotherapy within 120 days from surgical resection. A small proportion of patients assigned to this no-chemotherapy stage II group (2.6% in SEER-Medicare, 5.4% in NYSCR-Medicare, 10% in NYSCR-Medicaid) had a claim for chemotherapy between 121-240 days from surgical resection.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes were measured during an 8 month window from 30 days to 9 months post-resection. This start time was chosen because it could be reliably measured for all patients. Because median time to chemotherapy start in these cohorts was 40 days, this measure approximated the chemotherapy start date. The window encompasses the standard 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy, allowing for treatment delays and for the capture of immediate post-therapy outcomes.

Outcomes included outpatient AE claims; all-cause hospitalizations; all-cause ER visits not resulting in hospitalization; and 60 day mortality (from 30 days postsurgery). The incidence of specific chemotherapy-associated AEs (diarrhea, dehydration, nausea/ vomiting, neutropenia, infections, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus, acute coronary syndromes, transient ischemic attack/stroke) was examined using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes in outpatient records (codes available upon request). Finally, we examined the duration of chemotherapy, defined as the interval between the first and last dates of chemotherapy record.

The following covariates were available: age, sex, race, tumor substage, tumor grade, year of diagnosis, and income based on zip code of census tract. The Deyo and Klabunde modifications of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were measured based on claims from 1 to 13 months before the month of diagnosis.11-13

Statistical Analysis

The primary analytic focus of this study was to compare rates of adverse outcomes among patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin versus patients who received 5FU only. Because of stipulations surrounding data use and differences in ascertainment between SEER-Medicare and the NYSCR cohorts, results were not combined. Rather, outcomes were analyzed independently after applying consistent cohort specifications. Unadjusted and multivariate adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to compare outcomes between patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin and patients who received 5FU. All covariates were retained in multivariate models to facilitate cross-sample comparison. Analyses were conducted using the SAS software package (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Because our cohorts vary substantially in age composition (Medicaid aged <65 years, and Medicare patients aged ≥65 years) and because the underlying evidence base varies by age (the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients <75 years has been clearly demonstrated in clinical trials, but the benefit in patients > 75 years is unknown), we present all of our results stratified by age (< 75 years or ≥75 years). Though others have used age 70 as a cut point for subgroup analyses,14-16 we chose age 75 yers, because there is the least evidence for this age group in light of the recent report from Kahn et al and the findings from the MOSAIC trial, which excluded patients aged >75 years.5, 8

Because factors related to treatment selection, e.g. frailty, may be expected to confound the rate of adverse outcomes, we performed a propensity score (PS)-matched analysis in the patients who received chemotherapy to compare rates of adverse outcomes within patients who had a similar risk.17, 18 We generated a PS for the likelihood of oxaliplatin receipt from clinically relevant covariates (all covariates in Table 1), then matched 5FU/oxaliplatin patients with patients who had the same PS in the 5FU group. Patients for whom there was no match were excluded, creating a smaller cohort of patients balanced across treatment groups for measured confounders. Adverse outcomes were then compared in this similar risk group.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| SEER-Medicare 2003-2007 | NYSCR-Medicare, ≥65* 2002-2006 | NYSCR-Medicaid,<65** 2002-2006 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage II | Stage III | Stage II | Stage III | Stage II | Stage III | |

| No Chemotherapy | 8,902 (100%) | 3,706(47%) | 2,244 (100%) | 824 (34%) | 95 (100%) | 47 (12%) |

| 5FU, No Oxaliplatin | NA | 2,594(33%) | NA | 1,251 (52%) | NA | 290(72%) |

| 5FU and Oxaliplatin | NA | 1,605(20%) | NA | 319 (13%) | NA | 65 (16%) |

| Age (Median years, range) | 80 (32-103) | 77(31-105) | 80 (65-100) | 77 (65-101) | 55 (21-64) | 54 (25-64) |

| <50 | 40(0%) | 61(1%) | - | - | 26 (27%) | 128 (32%) |

| 50-64 | 235(3%) | 334(4%) | - | - | 69 (73%) | 274 (68%) |

| 65-69 | 1,072(12%) | 1,309(17%) | 206 (9%) | 431 (18%) | - | - |

| 70-74 | 1,403(16%) | 1,443(18%) | 322 (14%) | 453 (19%) | - | - |

| 75-79 | 1,839(21%) | 1,677(21%) | 556 (25%) | 540 (23%) | - | - |

| 80-84 | 2,201(25%) | 1,645(21%) | 584 (26%) | 539 (23%) | - | - |

| ≥85 | 2,112(24%) | 1,436(18%) | 576 (26%) | 431 (18%) | - | - |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 5,219(59%) | 4,537(57%) | 1317 (59%) | 1410 (59%) | 51 (54%) | 216 (54%) |

| Male | 3,683(41%) | 3,368(43%) | 927 (41%) | 984 (41%) | 44 (46%) | 186 (46%) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 7,635(86%) | 6,545(83%) | 3,933 (87%) | 3,138 (84%) | 58 (61%) | 225 (56%) |

| Black | 692(8%) | 762(10%) | 445 (10%) | 426 (11%) | 22 (23%) | 129 (32%) |

| Asian† | 259(3%) | 273(3%) | 123 (3%) | 148 (4%) | 15 (16%) | 48 (12%) |

| Other | 316(4%) | 325(4%) | 35 (1%) | 26 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Latino | ||||||

| Yes | 428(5%) | 444(6%) | 67 (3%) | 153 (6%) | 25 (26%) | 102 (25%) |

| No | 8,474(95%) | 7,461(94%) | 2,177 (97%) | 2,241 (94%) | 70 (74%) | 300 (75%) |

| CCIˆ | ||||||

| 0 | 4,965(56%) | 4,571(58%) | 1,176 (52%) | 1,313 (55%) | 58 (61%) | 239 (59%) |

| 1 | 2,202(25%) | 1,956(25%) | 608 (27%) | 620 (26%) | 22 (23%) | 75 (19%) |

| ≥2 | 1,735(19%) | 1,378(17%) | 460 (20%) | 461 (19%) | 15 (16%) | 88 (22%) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 3,977(45%) | 3,834(49%) | 957 (43%) | 1,044 (44%) | 39 (41%) | 144 (36%) |

| Single | 830(9%) | 736(9%) | 259 (12%) | 345 (14%) | 38 (40%) | 163 (41%) |

| Widow/divorced† | 3,702(42%) | 3,042(38%) | 969 (43%) | 927 (39%) | 18 (19%) | 95(24%) |

| Other | 393(4%) | 293(4%) | 59 (3%) | 78 (3%) | 0 | 0 |

| AJCC stage | ||||||

| IIA/ IIIA | 6,173(69%) | 835(11%) | 2,068 (92%) | 272 (11%) | 87 (92%) | 43 (11%) |

| IIB/IIIB | 733(8%) | 4,602(58%) | 176 (8%) | 1,370 (57%) | + | 216 (54%) |

| IIIC | 0 | 2,425(31%) | 0 | 752 (31%) | + | 143 (36%) |

| IIINOS | 1,996(22%) | 43(1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median Income | ||||||

| Top quantile | 2,225(25%) | 1,975(25%) | 587 (26%) | 607 (25%) | 13 (14%) | 34 (8%) |

| 3rd quantile | 2,225(25%) | 1,976(25%) | 765 (34%) | 824 (34%) | 23 (24%) | 116 (29%) |

| 2nd quantile† | 2,226(25%) | 1,975(25%) | 871 (39%) | 906 (38%) | 59 (62%) | 214 (53%) |

| 1st quantile | 2,224(25%) | 1,975(25%) | 21 (1%) | 57 (2%) | - | 38 (9%) |

| Diagnosis Year | ||||||

| 2002 | - | - | 418 (19%) | 469 (20%) | 12 (13%) | 54 (13%) |

| 2003 | 1,996(22%) | 1,882(24%) | 380 (17%) | 429 (18%) | 13 (14%) | 57 (14%) |

| 2004 | 1,906(21%) | 1,744(22%) | 504 (22%) | 531 (22%) | 21 (22%) | 96 (24%) |

| 2005 | 1,833(21%) | 1,734(22%) | 498 (22%) | 512 (21%) | 25 (26%) | 96 (24%) |

| 2006 | 1,740(20%) | 1,454(18%) | 444 (20%) | 453 (19%) | 24 (25%) | 99 (25%) |

| 2007 | 1,427(16%) | 1,091(14%) | - | - | - | - |

“NYSCR-Medicare ≥65” includes patients 65 years of age and older with any Medicare enrollment.

“NYSCR-Medcaid <65” includes patients less than 65 years of age with any Medicaid enrollment.

CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index estimated by Deyo-Klabunde modification in SEER and Deyo modification in NYSCR.

Asian/Other; Widowed/Divorced/Other; and bottom income quartiles merged in NYSCR-Medicaid to ensure confidentiality.

N≤11. Value omitted to ensure confidentiality.

RESULTS

In total, 21,942 patients with stage II and III colon cancer met criteria for inclusion, including 16,807 from the SEER-Medicare database, 4,638 from the NYSCR-Medicare database, and 497 from the NYSCR-Medicaid database (Table 1). The demographic distribution of the cohorts varied. The NYSCR-Medicaid sample was younger and had larger non-white (43%) and Latino populations than the Medicare samples.

Thirty-eight percent of the 4,199 patients with stage III disease who received chemotherapy in the SEER-Medicare sample received 5FU/oxaliplatin, compared with 18% of 355 patients who received chemotherapy in the NYSCR-Medicaid sample (aged <65 years) and 20% of 1570 patients who received chemotherapy in the NYSCR-Medicare sample (aged ≥65 years). The factor most consistently associated with oxaliplatin use was age: Oxalipltain use decreased with increasing age. Year of diagnosis was also an important determinant: The use of oxaliplatin increased over time.19

Adverse Outcomes

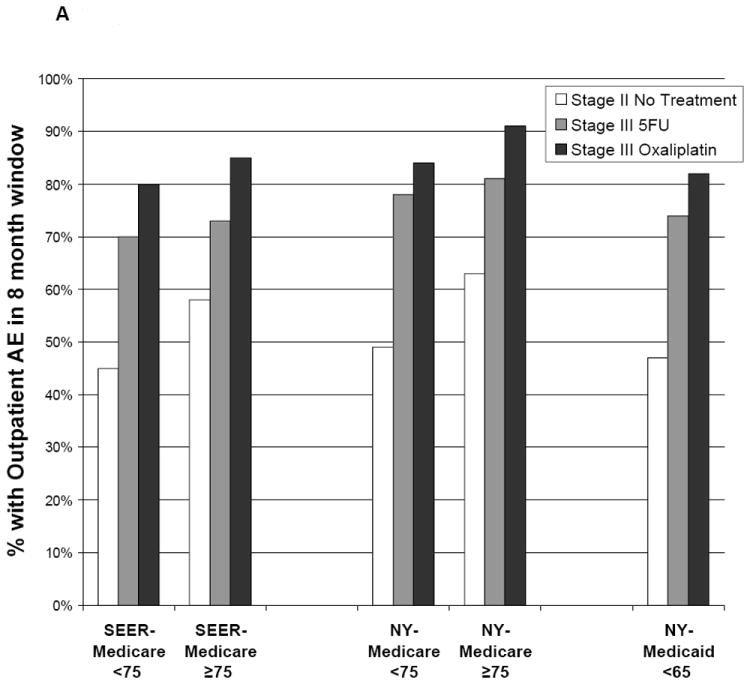

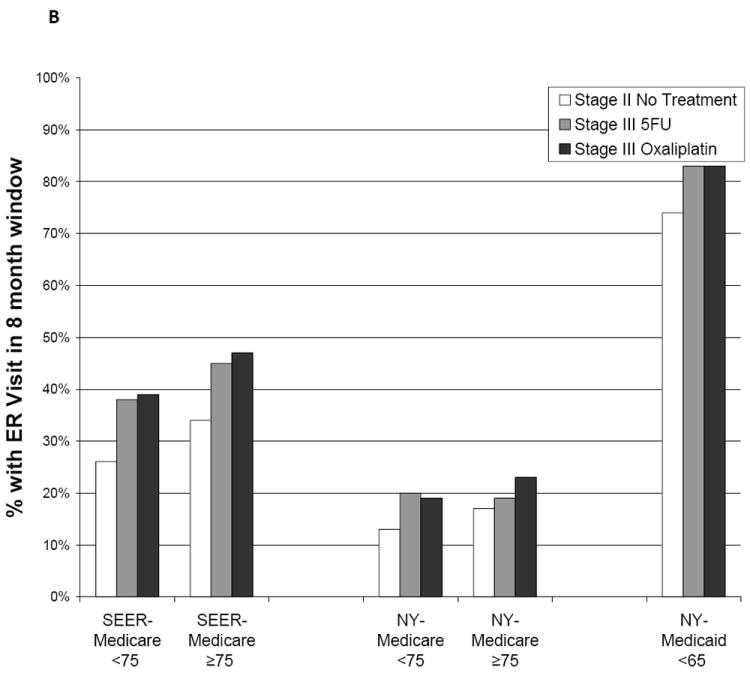

Patients who received chemotherapy had a greater number of outpatient AEs recorded in claims from 1 month to 9 months postresection than untreated patients with stage II disease; patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin consistently had the most AE claims. In SEER-Medicare, 54% of untreated patients with stage II disease had an AE claim compared to 72% of patients who received 5FU and 81% of patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin (Table 2, Figure 2). Corresponding AE rates in NYSCR-Medicare were 59% of untreated patients with stage II disease, 80% of patients who received 5FU, and 87% of patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin. AE rates in NYSCR-Medicaid were 47% for patients with untreated stage II disease, 74% for patients who received 5FU, and 82% for patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin. The adjusted odds of an AE were increased by oxaliplatin for all cohorts and were similar in the PS-matched analysis (Table 3). The most commonly identified AEs among all patients who received chemotherapy were diarrhea, dehydration, and nausea and/or vomiting (Table 4).

Table 2.

Effect of Adjuvant Therapy on Adverse Outcomes

|

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient Adverse Events | ER Visits | Hospitalizations | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Stage II | Stage III | Stage III | *OR, 95% CI | Stage II | Stage III | Stage III | *OR, 95% CI | Stage II | Stage III | Stage III | *OR, 95% CI | |

| No Chemo | 5FU | Ox | Ox vs. 5FU | No Chemo | 5FU | Ox | Ox vs. 5FU | No Chemo | 5FU | Ox | Ox vs. 5FU | |

|

SEER-MEDICARE

| ||||||||||||

| ALL AGES | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 8,902 | 2,594 | 1,605 | - | 8,902 | 2,594 | 1,605 | - | 8,902 | 2,594 | 1,605 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 4,807 | 1,857 | 1,307 | 1.84 | 2,790 | 1,074 | 663 | 1.11 | 2,628 | 1,072 | 618 | 1.01 |

| % affected | 54% | 72% | 81% | (1.53-2.21) | 31% | 41% | 41% | (0.95-1.30) | 30% | 41% | 39% | (0.86-1.18) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| <75 Years | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 2,750 | 1,214 | 1,141 | - | 2,750 | 1,214 | 1,141 | - | 2,750 | 1,214 | 1,141 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 1,233 | 845 | 913 | 1.75 | 719 | 456 | 446 | 1.05 | 694 | 467 | 432 | 1.1 |

| % affected | 45% | 70% | 80% | (1.39-2.21) | 26% | 38% | 39% | (0.86-1.30) | 25% | 38% | 38% | (0.89-1.35) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ≥75 Years | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 6,152 | 1,380 | 464 | - | 6,152 | 1,380 | 464 | - | 6,152 | 1,380 | 464 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 3,574 | 1,012 | 394 | 2.1 | 2,071 | 618 | 217 | 1.18 | 1,934 | 605 | 186 | 0.91 |

| % affected | 58% | 73% | 85% | (1.53-2.87) | 34% | 45% | 47% | (0.92-1.51) | 31% | 44% | 40% | (0.71-1.17) |

|

| ||||||||||||

|

NYSCR-MEDICARE

| ||||||||||||

| ALL AGES | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 2,244 | 1,251 | 319 | 2,244 | 1,251 | 319 | 2,244 | 1,251 | 319 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 1,332 | 1,000 | 276 | 1.84(1.25-2.75) | 356 | 241 | 65 | 1.09(0.77-1.55) | 954 | 669 | 134 | 0.63(0.47-0.84) |

| % affected | 59% | 80% | 87% | 16% | 19% | 20% | 43% | 53% | 42% | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 65-75 Years | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 528 | 541 | 202 | 528 | 541 | 202 | 528 | 541 | 202 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 259 | 422 | 169 | 1.40(0.85-2.33) | 68 | 108 | 38 | 1.03(0.63-1.68) | 172 | 272 | 82 | 0.57(0.39-0.85) |

| % affected | 49% | 78% | 84% | 13% | 20% | 19% | 33% | 50% | 41% | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| ≥75 Years | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 1,716 | 710 | 117 | 1716 | 710 | 117 | 1,716 | 710 | 117 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 1,073 | 578 | 107 | 2.87(1.45-6.25) | 288 | 133 | 27 | 1.26(0.74-2.11) | 782 | 397 | 52 | 0.66(0.42-1.03) |

| % affected | 63% | 81% | 91% | 17% | 19% | 23% | 46% | 56% | 44% | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

NYSCR-MEDICAID

| ||||||||||||

| <65 Years | ||||||||||||

| N eligible | 95 | 290 | 65 | 95 | 290 | 65 | 95 | 290 | 65 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N affected | 45 | 215 | 53 | 1.66(0.80-3.67) | 70 | 240 | 54 | 1.03(0.46-2.43) | 16 | 140 | 26 | 0.57(0.30-1.04) |

| % affected | 47% | 74% | 82% | 74% | 83% | 83% | 17% | 48% | 40% | |||

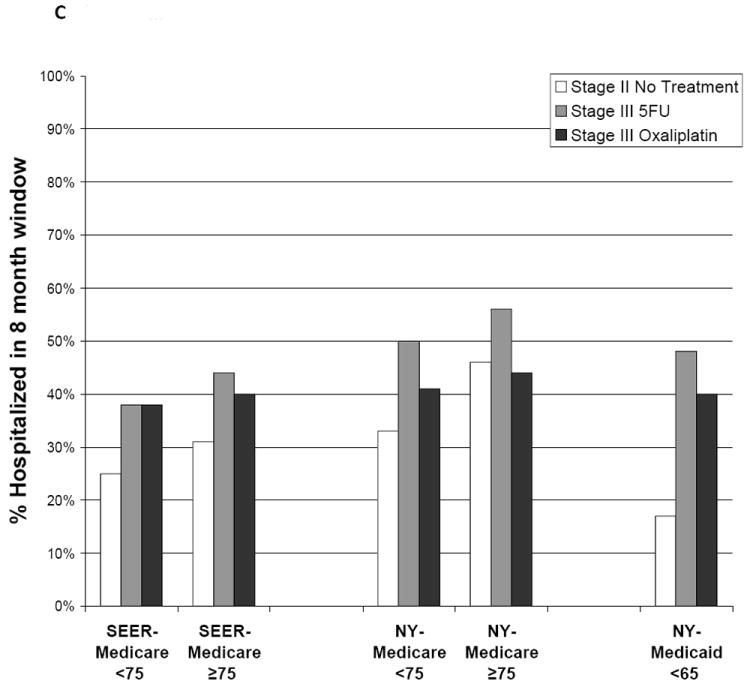

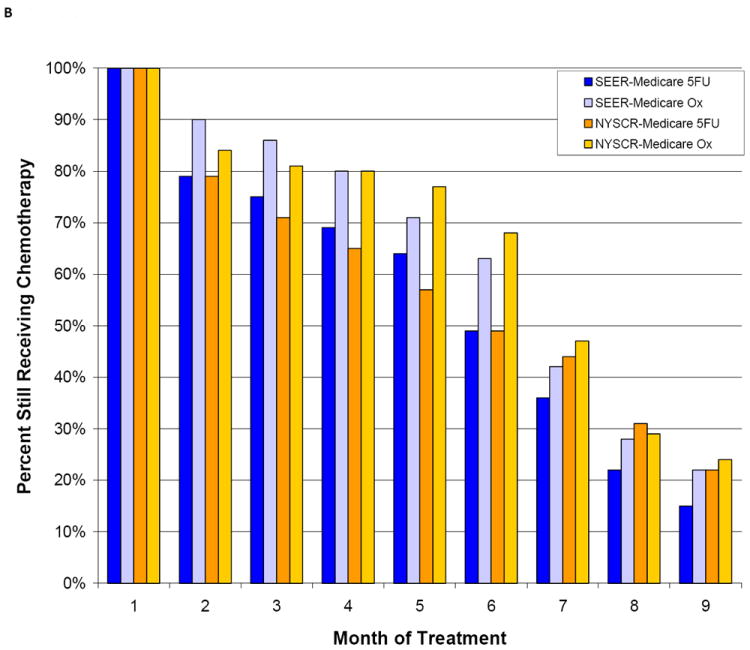

Figure 2.

Adverse outcomes are illustrated according to postoperative treatment. Outcomes were measured during an 8-month window beginning 30 days after patients underwent surgical resection. (A) Outpatient adverse events are illustrated, including diarrhea, dehydration, nausea/vomiting, neutropenia, infections, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus, acute coronary syndromes, transient ischemic attack, stroke, and neuropathy. 5FU indicates 5-fluorouracil; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. (B) Emergency room (ER) visits are illustrated. (C) Hospitalizations are illustrated.

Table 3.

Effect of Adjuvant Therapy on Adverse Outcomes in Propensity Score Matched Patients

|

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient Adverse Events | ER Visits | Hospitalizations | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | *OR, 95% CI Oxaliplatin vs. 5FU | Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | *OR, 95% CI Oxaliplatin vs. 5FU | Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | *OR, 95% CI Oxaliplatin vs. 5FU | |

|

SEER-MEDICARE

| |||||||||

| ALL AGES | |||||||||

| N eligible | 952 | 952 | 952 | 952 | 952 | 952 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 672 | 779 | 1.94 | 374 | 416 | 1.22 | 370 | 365 | 0.98 |

| % affected | 71% | 82% | (1.56-2.41) | 39% | 44% | (1.01-1.46) | 39% | 38% | (0.82-1.18) |

|

| |||||||||

| <75 Years | |||||||||

| N eligible | 573 | 562 | 573 | 562 | 573 | 562 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 395 | 447 | 1.77 | 212 | 231 | 1.18 | 210 | 210 | 1.03 |

| % affected | 69% | 80% | (1.35-2.33) | 37% | 41% | (0.93-1.51) | 37% | 37% | (0.81-1.32) |

|

| |||||||||

| ≥75 Years | |||||||||

| N eligible | 379 | 390 | 379 | 390 | 379 | 390 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 277 | 332 | 2.29 | 162 | 185 | 1.25 | 160 | 155 | 0.93 |

| % affected | 73% | 85% | (1.58-3.31) | 43% | 47% | (0.93-1.66) | 42% | 40% | (0.69-1.24) |

|

| |||||||||

|

NYSCR-MEDICARE

| |||||||||

| ALL AGES | |||||||||

| N eligible | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 228 | 243 | 1.62 | 66 | 57 | 0.83 | 162 | 118 | 0.50 |

| % affected | 81% | 86% | (1.01-2.63) | 23% | 20% | (0.55-1.26) | 58% | 42% | (0.35-0.71) |

|

| |||||||||

| 65-75 Years | 168 | 167 | 168 | 167 | 168 | 167 | |||

| N eligible | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 134 | 139 | 1.35 | 36 | 31 | 0.84 | 94 | 66 | 0.50 |

| % affected | 80% | 83% | (0.75-2.43) | 21% | (19%) | (0.48-1.48) | 56% | 40% | (0.31-0.79) |

|

| |||||||||

| ≥75 Years | 113 | 114 | 113 | 114 | 113 | 114 | |||

| N eligible | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 94 | 104 | 2.44 | 30 | 26 | 0.81 | 68 | 52 | 0.47 |

| % affected | 83% | 91% | (1.00-6.39) | 27% | 23% | (0.42-1.54) | 60% | 46% | (0.26-0.83) |

|

| |||||||||

|

NYSCR-MEDICAID

| |||||||||

| <65 Years | |||||||||

| N eligible | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| N affected | 50 | 51 | 1.23 | 51 | 52 | 0.95 | 35 | 25 | 0.46 |

| % affected | 79% | 81% | (0.44-3.52) | 81% | 83% | (0.32-2.80) | 56% | 40% | (0.20-1.02) |

Ox, Oxaliplatn.

Adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, sex, income, marital status, comorbidity index, tumor substage, year of diagnosis.

Table 4.

Incidence of Chemotherapy Associated Adverse Events

| SEER-Medicare | NYSCR-Medicare | NYSCR-Medicaid | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Stage II, No Rx | Stage III, No Rx | Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | OR, 95% CI Ox vs. 5FU | Stage II, no Rx | Stage III, no Rx | Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | OR, 95% CI Ox vs. 5FU | Stage II, No Rx | Stage III, No Rx | Stage III 5FU | Stage III Ox | OR, 95% CI Ox vs. 5FU | |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| N, TOTAL | 8,902 | 3,706 | 2,594 | 1,605 | - | 2,244 | 824 | 1,251 | 319 | - | 95 | 47 | 290 | 65 | - |

| <75 N eligible* | 2,750 | 792 | 1,214 | 1,141 | 528 | 141 | 541 | 202 | 95 | 47 | 290 | 65 | |||

| ≥75 N eligible | 6,152 | 2,914 | 1,380 | 464 | 1,716 | 683 | 710 | 117 | - | - | - | - | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 11% | 18% | 30% | 34% | 0.83(0.70-0.99) | 12% | 11% | 30% | 29% | 0.94(0.66-1.33) | 14% | + | 23% | 20% | 0.85(.42-1.61) |

| Age ≥75 | 12% | 15% | 38% | 31% | 0.74(0.59-0.93) | 12% | 15% | 33% | 32% | 0.99(0.65-1.50) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Dehydration | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 16% | 31% | 38% | 42% | 1.20(1.02-1.41) | 13% | 28% | 35% | 32% | 0.87(0.61-1.23) | + | + | 25% | 18% | 0.69(.33-1.32) |

| Age ≥75 | 21% | 29% | 44% | 46% | 1.08(0.88-1.33) | 23% | 29% | 41% | 42% | 1.04(0.70-1.55) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Nausea/vomiting | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 8% | 17% | 35% | 51% | 1.93(1.63-2.27) | 7% | 16% | 45% | 65% | 2.31(1.66-3.25) | + | + | 32% | 49% | 2.02(1.17-3.5) |

| Age ≥75 | 9% | 13% | 32% | 51% | 2.14(1.73-2.65) | 7% | 14% | 37% | 74% | 4.87(3.17-7.68) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Neutropenia | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | <1% | <1% | 1% | 14% | 13.2(7.74-22.60) | 0% | + | 2% | 10% | 5.11(2.50-10.9) | 0% | 0% | + | + | 5.96(1.5-24.7) |

| Age ≥75 | <1% | <1% | 1% | 16% | 17.3(9.80-30.42) | <1% | 0% | + | 12% | 19.2(7.17-60.3) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Infection | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 24% | 39% | 25% | 29% | 1.22(1.02-1.47) | 26% | 35% | 31% | 28% | 0.84(0.58-1.19) | 28% | 34% | 36% | 32% | 0.84(0.47-1.5) |

| Age ≥75 | 33% | 40% | 30% | 32% | 1.09(0.87-1.36) | 36% | 43% | 40% | 33% | 0.74(0.49-1.11) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| DVT /PE | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | 3.20(0.33-30.8) | 5% | 12% | 15% | 16% | 1.09(0.70-1.68) | + | + | 12% | + | 0.85(0.33-1.9) |

| Age ≥75 | <1% | 0% | <1% | <1% | 5.97(0.54-66.0) | 7% | 9% | 15% | 17% | 1.16(0.67-1.93) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| ACS | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 18% | 28% | 20% | 13% | 0.61(0.49-0.76) | 18% | 33% | 24% | 13% | 0.49(0.31-0.76) | 14% | + | 20% | + | 0.55(.23-1.16) |

| Age ≥75 | 29% | 33% | 23% | 21% | 0.89(0.69-1.16) | 31% | 40% | 31% | 18% | 0.48(0.28-0.77) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| TIA/CVA | |||||||||||||||

| Age < 75 | 7% | 9% | 7% | 6% | 0.93(0.67-1.29) | 8% | 9% | 8% | 7% | 0.91(0.47-1.66) | + | + | 5% | + | 0.29(.02-1.45) |

| Age ≥75 | 11% | 12% | 10% | 10% | 0.98(0.69-1.39) | 12% | 11% | 12% | + | 0.54(0.24-1.08) | - | - | - | - | - |

NYSCR-Medicare patients are ≥ 65 years. NYSCR-Medicaid patients are < 65 years.

N≤11. Value omitted to ensure confidentiality.

There was modest evidence of increased toxicity from 5FU/oxaliplatin relative to 5FU with advancing age. In the SEER-Medicare and NYSCR-Medicare samples, the adjusted odds of an AE between 5FU and oxaliplatin among patients aged ≥75 years were greater than the odds among patients aged <75 years, and a similar trend was observed in the PS-matched cohorts. Further age stratification in the SEER-Medicare sample revealed a trend towards an increasing effect on AEs with age: (ages 65-59: odds ration [OR], 1.67; 95%CI 1.24-2.24; ages 70-74 OR 3.18, 95% CI 0.38-26.3; ages 75-79, OR 1.80 95% CI 1.27-2.55; ages 80-84, OR 3.37, 95%CI 1.74-6.51; ages ≥85, OR 3.18, 95% CI 0.38-26.8).

Combined 5FU/oxaliplatin was not associated with increased ER use. In the SEER-Medicare sample, 41% of patients who received 5FU and 41% of patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin required an ER visit, though a 5% increase in ER use among patients who received oxaliplatin was observed in the PS-matched analysis (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01-1.46). Oxaliplatin did not increase ER use in either NYSCR cohort. However, ER use in NYSCR-Medicaid cohort was exceptionally high, and 74% of patients with untreated stage II disease and 83% of both chemotherapy groups visited an ER 1 month to 9 months after undergoing resection.

Hospitalization was more common in patients who received 5FU than in patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin; in the NYSCR-Medicare sample, there was a significant decrease in the adjusted odds of hospitalization in those who received oxaliplatin (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.47-0.84) that persisted with PS matching. However, all chemotherapy-treated patients were hospitalized more commonly than patients with untreated stage II disease. This trend was most pronounced in the NYSCR-Medicaid population, in which 17% of patients who had untreated stage II disease were hospitalized compared with 40% of patients who had stage III disease and received oxaliplatin. Hospitalization rates among patients aged ≥75 years were high even in the patients with untreated stage II disease (SEER-Medicare sample, 31%; NYSCR-Medicare sample, 46%).

In stratified analyses, there was no consistent evidence of a differential or increased risk of ER use or hospitalization from 5FU/oxalipatin, including the 2 commonly cited factors for omitting oxaliplatin: advanced age or comorbidity. The mortality rate between 30 days and 90 days after resection, the surrogate for 60-day treatment mortality, was ≤3% in all subgroups.

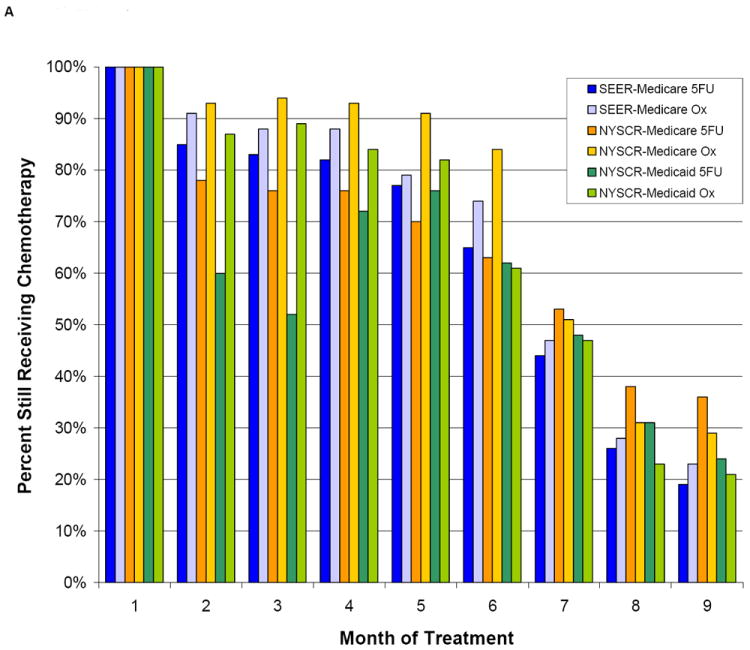

Duration of Chemotherapy

In both age cohorts, fewer patients who received 5FU than patients who received FU/oxaplatin still had claims for chemotherapy 9 months after initiating treatment, suggesting a shorter duration of chemotherapy was more common in patients who received 5FU than in patients who received oxaliplatin (Figure 3). Eight months after starting chemotherapy, a large proportion of patients still had claims for chemotherapy even in the PS-matched cohort (NYSCR-Medicaid sample: 5FU, 31% ; 5FU/oxaliplatin, 23%).

Figure 3.

The duration of adjuvant chemotherapy is illustrated according to the propensity score (PS) in (A) PS-matched patients aged <75 years and (B) PS-matched patients aged ≥75 years. SEER indicates Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; Ox, oxaliplatin.

DISCUSSION

Adjuvant chemotherapy improves the chance of cure for patients with resected stage III colon cancer aged< 75 years. The standard of care regimen of 5FU with modulating leucovorin, plus oxaliplatin increases severe neutropenia, nausea and vomiting, and diarrhea. Despite this toxicity, in the MOSAIC trial 75% of patients received all of the planned cycles, and 80% of the planned oxaliplatin dose was delivered in those cycles,5 suggesting that the toxicity from this regimen is manageable with proper supportive care.

By using population-based registry data linked to administrative claims to compare rates of adverse outcomes in chemotherapy-treated patients with stage III colon cancer, we observed higher rates of AEs in chemotherapy-treated patients compared to a control group of patients with stage II colon cancer who underwent similar surgery but did not receive any chemotherapy. We also observed higher rates of AEs in patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin compared with patients who received 5FU. Despite more AEs between 1 month to 9 months after surgical resection, patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin were not more likely to require ER visits or hospitalization. The toxicity of 5FU/oxaliplatin relative to that of 5FU, as measured by AE claims, was more pronounced in patients aged≥75 years; however age did not modify the effect of oxaliplatin on ER visits or hospitalizations.

Our findings of higher AE rates in patients who received oxaliplatin and of relatively greater toxicity from 5FU/oxaliplatin in older patients conflict with recent results from CanCORS. CanCORS is a study of incident cases of stage III colon cancer from a heterogeneously sampled group of health systems which approximates a population-based sample. In CanCORS, after excluding peripheral neuropathy, which we did not include in our investigation of claims-based outpatient AEs, there was no difference in the mean number of AEs between patients who did and did not receive oxaliplatin. Patients aged ≥75 years who received chemotherapy in CanCORS were less likely to experience adverse outcomes between 1 month to 15 months after surgical resection than were patients ages 55 to 74 years.8 AEs were ascertained very differently in these 2 investigations: CanCORS used medical record abstraction in CanCORS, and we used claims in our study. Although it seems reasonable to anticipate better AE capture from medical record review than from claims, only 24% of patients aged >75 years in CanCORS who received chemotherapy experienced a chart-abstracted AE compared with 76% of our SEER-Medicare patients aged≥75 years with a claim-based AE.

Although oxaliplatin did not increase the need for hospitalization, rates of hospitalization in our sample of older (Medicare) and disadvantaged (Medicaid) Americans with colon cancer were exceptionally high. Between 38 to 56% of all patients we examined who received chemotherapy required hospitalization during the interval between 31 days to 9 months after resection of their cancer. In contrast, in the CanCORS study, only 13 to 19% of patients required hospitalization from 1 to 15 months after surgery, which may be related to lower rates of ascertainment of hospitalization through medical record review or differences in patient sample. In neither CanCORS nor our claims-based analyses was there any evidence of an increased need for hospitalization with age.

ER use was particularly frequent in NYSCR-Medicaid patients. Compared with an estimated 24% of general Medicaid patients using the ER annually,20 74% of patients with stage II disease and 83% of patients who received oxaliplatin in the NYSCR-Medicaid sampled used the ER. This exceptionally high rate of ER use is probably related less to treatment than to health system factors, such as barriers to seeking care from oncologists related to communication, race and poverty. Our results should prompt development of strategies to optimally support Medicaid-insured patients during adjuvant chemotherapy with the objective of minimizing ER use, which is not optimized for symptom management, and thus, improving health outcomes. Because this effectiveness research is conducted in collaboration with the leadership of the NY State Health Department, these results can be used to inform care design at the local level.

We observed the duration of chemotherapy in this community sample differed substantially from the standard 6-month course. Although a chemotherapy duration of <4 months was associated previously with increased mortality in patients with stage III colon cancer who received 5FU in the SEER-Medicare database,21 that may be related to factors associated with discontinuation. Indeed, there is some suggestion that six months may not be required,22 a issue that is being addressed by the currently enrolling clinical Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) trial 80702. With that in mind, we were surprised to observe that nearly 1 in 5 patients was still receiving chemotherapy 9 months after the initiation of treatment. A small proportion of these patients likely continued therapy because they developed metastatic disease. Others may have required dose delays for toxicity; however, it is unknown whether continuing chemotherapy for as long as 9 months after surgical resection has any effect on micrometastatic cancer.

The current results are limited by the nature of administrative claims data. Claims best capture AEs of sufficient severity to require an intervention and rely on the physician’s thoroughness in coding.23 Indeed, for that reason, we did not investigate the most common AE of oxaliplatin: neuropathy. Certainly if we were able to accurately capture neuropathy, then the AE rate in patients who received 5FU/oxaliplatin would have been higher. Also, patients with more comorbidity may be less likely to have treatment-related AEs coded when competing illnesses better meet requirements for billing a “complex” Evaluation and Management code. Such differential reporting may be expected to decrease AE capture in older and sicker patients. Rates of hospitalization and ER use, however, are less dependent on coding practice. Between 2 to 10% of our control group of patients with untreated stage II disease received some chemotherapy during the observation window, which slightly diminishes our ability to conclude causality with regard to higher adverse events in patients with stage III disease. In addition, we attempted to address selection bias through PS matching; however, such methods cannot account for unmeasured confounding. If patients who received 5FU were inherently sicker than the oxaliplatin cohort, they might have greater rates of adverse outcomes regardless of chemotherapy treatment.

Acknowledging these limitations, we observed small increases in AEs among patients with stage III colon cancer who received 5FU/oxaliplatins compared with patients who received 5FU. Among patients aged≥75 years, we observed a modest differential increase in AEs from oxaliplatin but without increased need for ER visits or hospitalizations. These data provide additional evidence that, although oxaliplatin does increase AEs, for most patients, this does not extend to include severe and life-threatening toxicities that require hospitalization. By using a similar multi-cohort strategy we have also found adjuvant therapy to retain its effectiveness in the community.19 Our results support oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy as the standard of care for adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer in the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Jennifer Wind for her many invaluable contributions to this project.

The Institutional Review Board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute approved this study (IRB #08-338).

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. This resource has been made available to the research community through collaborative efforts of the NCI and CMS. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

This study used the linked NYSCR-Medicare and Medicaid database. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the NYS Cancer Registry and NYS Medicaid Program.

Funding Funding sources were not directly involved with the design, analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services through Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness program; Contract HSA290-2005-0016-I-TO7-WA1, 36-BWH-1; HHSA290-2005-0040-I-TO4-WA1, 36-UNC. The authors are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by AHRQ or the US Department of HHS.

The National Cancer Institute, R01CA131847; 1R25CA116339.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the Association of Schools of Public Health, S3888 (Schymura, PI)

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Authors report no financial COI.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1797–1806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990;264:1444–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjarnason NH. Disparities in participation in cancer clinical trials. JAMA. 2004;292:922. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.922-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use and adverse events among older patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1037–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCI. [May 24, 2011];SEER-Medicare: Brief Description of the SEER-Medicare Database. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview/

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1091–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, et al. Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4085–4091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCleary NAJ, Meyerhardt J, Green E, et al. Impact of older age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in >12,500 patients with stage II/III colon cancer: Findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15s) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6638. abstr 4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects form large data sets using propensity scores. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons L. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. [1 August 2011];2001 http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf.

- 19.Sanoff H, Carpenter W, Martin C, et al. Effectiveness of Oxaliplatin-Containing Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. JNCI. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr524. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handel DA, McConnell KJ, Wallace N, Gallia C. How much does emergency department use affect the cost of Medicaid programs? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:614–621. 621–e611. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neugut AI, Matasar M, Wang X, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2368–2375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. A randomised comparison between 6 months of bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin and 12 weeks of protracted venous infusion fluorouracil as adjuvant treatment in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:549–557. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potosky AL, Warren JL, Riedel ER, Klabunde CN, Earle CC, Begg CB. Measuring complications of cancer treatment using the SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-62–68. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]