Abstract

Type 2 diabetes is known to cause endothelial activation resulting in the secretion of von Willebrand factor (VWF). We have shown that levels of VWF in a glycoprotein Ib-binding conformation are increased in specific clinical settings. The aim of the current study is to investigate whether active VWF levels increase during aging and the development of diabetes within the population of patients suffering from type 2 diabetes. Patients and controls were divided into two groups based on age: older and younger than 60 years of age. VWF antigen, VWF propeptide, VWF activation factor and total active VWF were measured. Patients older than 60 years of age had increased levels of total active VWF, VWF activation factor and VWF propeptide compared to younger patients and controls. All measured VWF parameters were associated with age in diabetic patients. Total active VWF and VWF propeptide correlated with the period of being diagnosed with diabetes. Regression analyses showed that especially the VWF activation factor was strongly associated with diabetes in patients older than 60 years of age. In conclusion, we found that the conformation of VWF could be involved in the disease process of diabetes and that the VWF in a glycoprotein Ib-binding conformation could play a role as risk marker during the development of diabetes in combination with an increase in age. Our study shows that the active quality of VWF was more important than the quantity.

Keywords: Diabetes, Aging, VWF antigen, VWF activation factor, Total active VWF

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes, formerly known as non-insulin dependent diabetes, is caused by insulin resistance leading to high levels of glucose in the blood. Patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are known to have a higher incidence of thrombotic complications (Frankel et al. 2008). Multiple causes have been proposed to explain the observed prothrombotic state. With respect to this prothrombotic state, endothelial activation has been shown to occur in patients suffering from type 2 diabetes (Natali et al. 2006). Von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a multimeric glycoprotein produced by vascular endothelial cells and is frequently used as a marker for endothelial activation (Sadler 1998; Ruggeri 1999; Blann 2006). When endothelial cells become activated, VWF and its propeptide are released from the Weibel–Palade bodies in equimolar concentrations (Wagner et al. 1987). VWF propeptide has a five- to sixfold shorter half-life compared to VWF. Therefore, the ratio of VWF/pro-VWF can be used to study acute versus chronic endothelial cell perturbation (van Mourik et al. 1999; Hollestelle et al. 2006; Vischer et al. 1998).

Our group has studied VWF having different conformations with VWF in a glycoprotein Ib (GPIb)-binding conformation as a major interest. Under normal circumstances, VWF is in a latent conformation, unable to bind GPIb on platelets. After endothelial perturbation, VWF is secreted in long stretches of multimers. The newly secreted ultra-large VWF is in its active conformation, able to bind spontaneously to the platelet receptor GPIb. This activity is downregulated by ADAMTS13, which is able to cleave the ultra-large VWF in smaller polymers of VWF. Under certain pathological conditions, activated VWF is present in the circulation in increased concentrations. With a specific antibody directed against the “active” conformation of VWF (spontaneous binding to platelet–receptor glycoprotein Ib), increased levels of active VWF could be demonstrated in various patients suffering from thrombotic complications (Groot et al. 2007; de Mast et al. 2009; Hollestelle et al. 2010; Jezovnik and Poredos 2010).

Several studies demonstrated that increased VWF levels are associated with age (Vischer 2006; Gill et al. 1987; Coppola et al. 2003; Favaloro et al. 2005). In particular, high levels of VWF antigen were demonstrated in centenarians showing that even at high age, VWF levels are still continuing to increase (Coppola et al. 2003). How age affects VWF levels in patients with diabetes is unknown. Furthermore, it is not known if and how VWF propeptide levels and active VWF are affected due to aging and whether they correlate with age. In the present study, we investigated VWF in type 2 diabetic patients by measuring active VWF together with VWF antigen and VWF propeptide levels. These results were correlated with age, duration of diabetes and other related clinical parameters.

Methods

Patients and control participants

To determine the relationship of VWF-related parameters in type 2 diabetic patients, we studied a group of 75 type 2 diabetic patients, recruited between October and November 2007 in Liaocheng People’ Hospital and Department of Aging Medicine, Taishan Medical University. The diagnosis was according to American Diabetes Association criteria (Ediger et al. 2009). Patients with additional inflammation complications were excluded from the study. It was based on clinical symptoms and the ruling out of common bacterial and viral pathogens, damaged cells or irritants that cause acute high-grade inflammation. Fifty-nine healthy volunteers were included in the study to serve as controls. The control participants did not have major chronic medical illnesses and were not taking any medication known to influence VWF-related parameters. No clinically significant abnormalities were found during the physical examination. Participants were not anaemic and had normal liver and kidney function. The institutional review board of Liaocheng School of Clinical Medicine, Taishan Medical University approved the study. The study has been executed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent.

VWF-related parameter measurements

Venous blood samples were collected in 0.129 M trisodium citrate. The samples were centrifuged at 2,000×g for 20 min at 4°C and platelet-poor plasma was stored at −70°C. VWF antigen was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a rabbit anti-human VWF polyclonal antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for both VWF capture and detection. VWF propeptide antigen was measured by using in-house assay based on polyclonal rabbit-anti human propeptide antibodies (van Schooten et al. 2007). The VWF activation factor was determined by measuring the levels of activated VWF that specifically recognizes the active, GPIb-binding conformation by using the AU/VWFa-11 llama-derived nanobody, as described by (Hulstein et al. 2005). The VWF activation factor was calculated by dividing the absorbance slope of a patient sample to the slope of the corresponding standard sample (normal plasma from a pool of more than 150 adult donors served as standard, NPP) and correct them for VWF antigen levels. By using this method, the VWF activation factor is calculated, which describes the ratio of total active VWF per micrograms per milliliter VWF antigen. Total active VWF was calculated by multiplying the VWF activation factor with the VWF antigen levels and describes the number of active VWF expressed in percentages. NPP was set at 100%. The NPP contained 48 nM VWF antigen and 6.3 nM of VWF propeptide.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as a median and interquartile range and compared using a Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon test, unless otherwise stated. The Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the relationship between VWF-related parameters/age and VWF-related parameters/years of diabetes. A nonparametric ANOVA Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's post test were performed to compare the different VWF-related parameters. All reported P values are calculated based on two-sided tests. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 15.0. The graphics were made by GraphPad and Instat software (San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

The characteristics of the type 2 diabetic patients and the controls

The characteristics of the type 2 diabetic (n = 75) and the controls (n = 59) are summarized in Table 1. The patients and controls were divided into two groups: individuals below 60 years of age and individuals who are above 60 years of age. Glucose levels were significantly elevated in both diabetic patient groups, independent of age (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01). The older patients had a significantly higher incidence of hypertension (54%) and coronary artery disease (41%) (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) compared to diabetic patients below 60 years (29% and 3%, respectively). Furthermore, no difference was observed between the period of established diabetes in patients below or above 60 years of age (median in younger patients 6 years and in older patients 9 years, P > 0.05).

Table 1.

The characteristics of study participants

| Below 60 years | Above or equal 60 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 34) | Controls (n = 45) | P value | Patients (n = 41) | Controls (n = 14) | P value | P value, diabetes | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, years | 49.3 ± 8.3 | 44.8 ± 9.1 | 0.026 | 68.7 ± 6.3 | 67.4 ± 5.3 | NS | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 17 (50%) | 24 (53%) | NS | 18 (44%) | 3 (21%) | NS | NS |

| Duration of diabetes | 6.1 ± 5.5 | – | 9.1 ± 7.9 | – | NS | ||

| BMI | 25.4 (23.2–28.7) | 24.3 (23.5–26.4) | NS | 24.4 (22.3–26.5) | 25.7 (22.7–27.5) | NS | NS |

| Platelets (109/L) | 197 (168–272) | 173 (156–224) | NS | 199 (173–252) | 188 (152–216) | NS | NS |

| Glucose (mM) | 8.2 (6.5–11.2) | 4.4 (3.6–5.7) | <0.001 | 8.1 (6.1–10.3) | 5.6 (5.3–6.8) | 0.002 | NS |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 (6.2–11.0) | – | – | 7.9 (7.0–11.4) | – | – | NS |

| LDL (mM) | 3.0 (2.4–3.7) | 2.2 (1.8–2.5) | 0.001 | 3.1 (2.5–3.5) | – | – | NS |

| HDL (mM) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | NS | 1.2 (0.1–1.4) | – | – | NS |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 1.7 (1.3–2.5) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | – | – | 0.001 |

| SP-D (ng/ml) | 769 (356–1,219) | 265 (206–421) | <0.001 | 661 (262–1,131) | 279 (216–343) | 0.013 | NS |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 130 (120–140) | – | – | 135 (120–150) | – | – | NS |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 80 (80–90) | – | – | 80 (70–89) | – | – | 0.015 |

| Hypertension | 10 (29%) | – | – | 22 (54%) | – | – | 0.035 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (3%) | – | – | 17 (41%) | – | – | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 (0%) | – | – | 2 (5%) | – | – | NS |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 (6%) | – | – | 4 (10%) | – | – | NS |

Plus–minus signs are mean ± standard deviation (SD)

SP-D surfactant protein D, BMI body mass index, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HDL high-density lipoprotein

The relationship between the VWF-related parameters and age in diabetic patients and controls

At first, we investigated within the group of controls and the group of diabetic patients for possible associations between VWF and age. In the controls, we observed a correlation between age and VWF antigen as well as between age and total active VWF (R s = 0.352, P < 0.01 and R s = 0.259, P < 0.05, respectively, Table 2). In diabetic patients, correlations between VWF antigen and total active VWF were also observed (R s = 0.236, P < 0.05/R s = 0.350, P = 0.002, respectively, Table 2). In contrast to the control population, VWF propeptide and the VWF activation factor also correlated strongly with age in diabetic patients (R s = 0.394, P = 0.001 and R s = 0.373, P = 0.001, respectively, Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between VWF-related parameters and age

| Patients | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R s | P | R s | P | |

| VWF | 0.236 | 0.045 | 0.352 | 0.006 |

| VWF propeptide | 0.394 | 0.001 | 0.212 | NS |

| VWF activation factor | 0.373 | 0.001 | 0.027 | NS |

| Total active VWF | 0.350 | 0.002 | 0.259 | 0.048 |

The Spearman correlation coefficient R s and the P value were calculated to determine the relationship between VWF-related parameters and age

VWF von Willebrand factor

Duration of diabetes and VWF-parameters

Next, we analyzed whether there is a positive correlation between the period suffering from diabetes and VWF-related parameters. A significant positive correlation between VWF propeptide and years of diabetes was observed (R s = 0.395, P < 0.05, Table 3). The amount of total active VWF also proved to be positively associated with the time of having type 2 diabetes (R s = 0.323, P < 0.05, Table 3). No association was observed between the VWF-related parameters and glucose levels or HbA1c levels.

Table 3.

Correlations between VWF-related parameters and the duration of diabetes

| Patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| R s | P | |

| VWF | 0.288 | 0.075 |

| VWF propeptide | 0.395 | 0.017 |

| VWF activation factor | 0.169 | 0.297 |

| Total active VWF | 0.323 | 0.045 |

The Spearman correlation coefficient R s and the P value were calculated to determine the relationship between VWF-related parameters and suffering years of diabetic patients

VWF von Willebrand factor

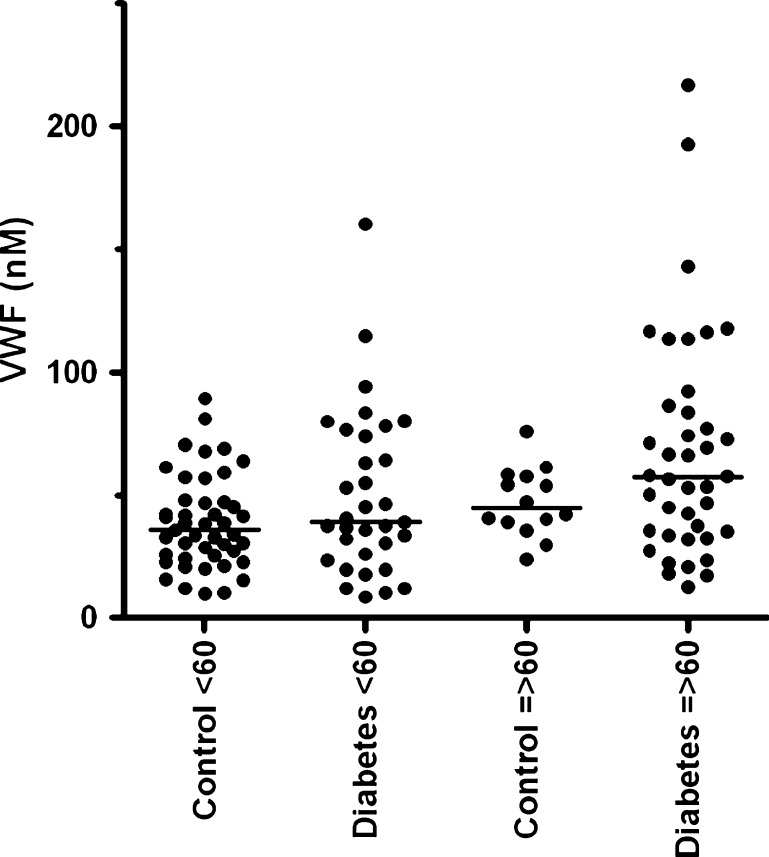

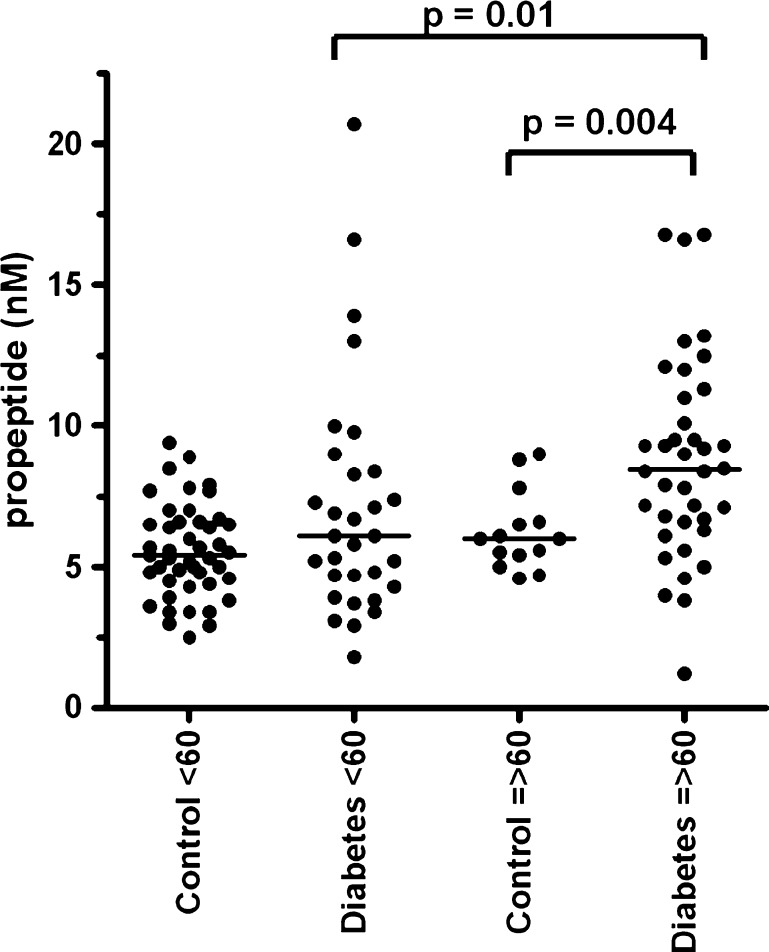

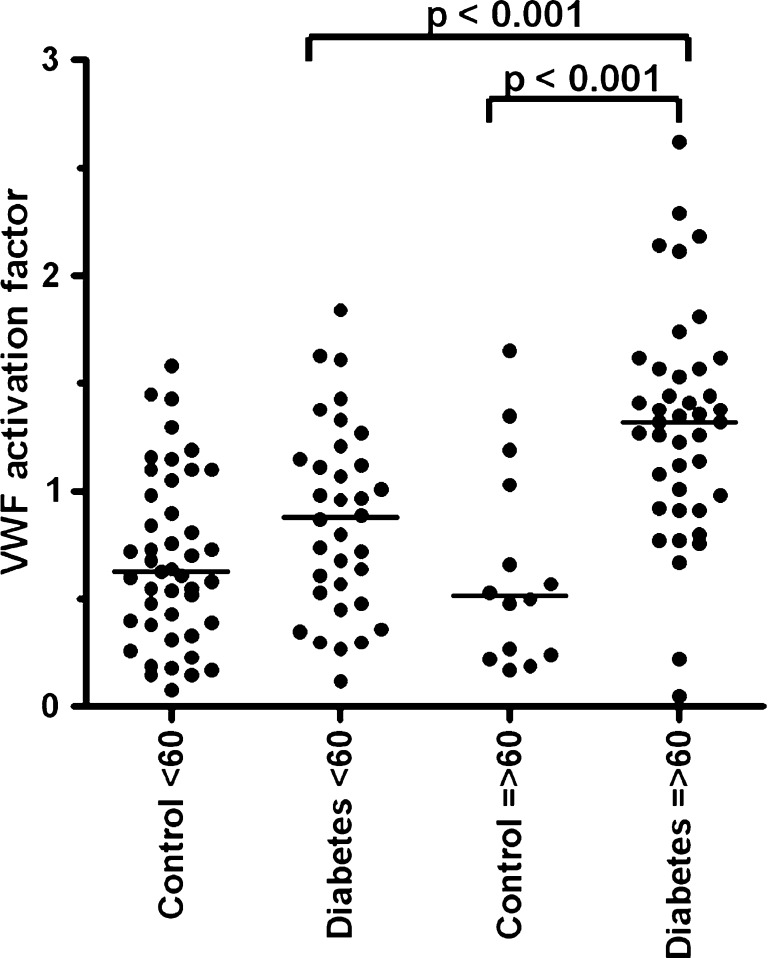

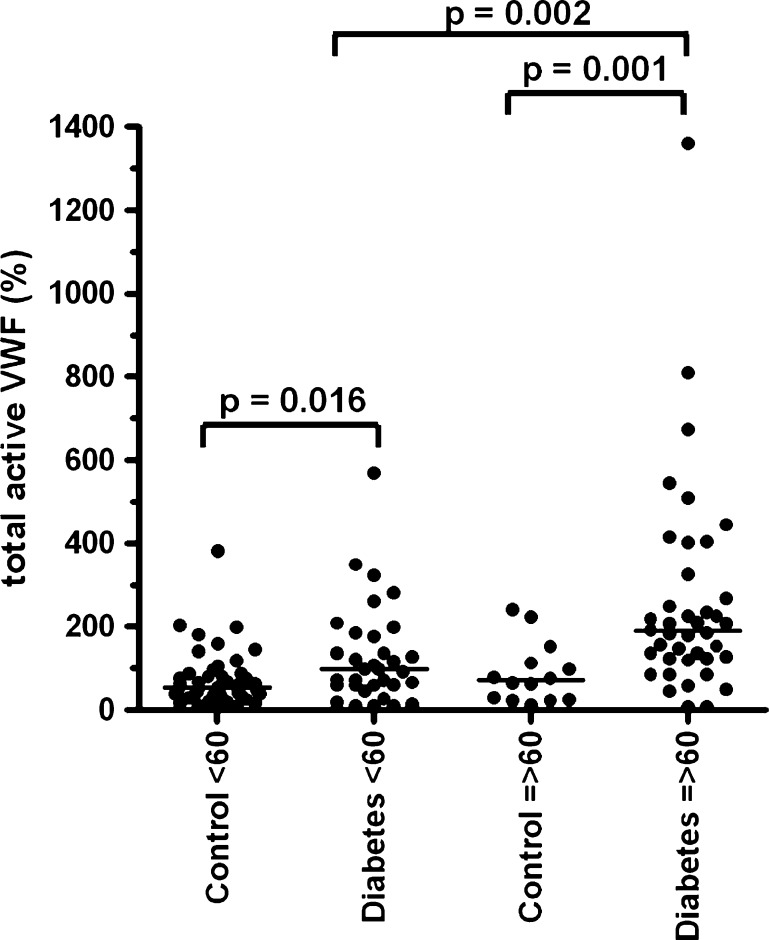

Differences between VWF parameters and the patient and control groups divided by age

We investigated possible differences between the controls and diabetic patients regarding VWF and age. No significant difference of VWF antigen levels was observed between the controls and diabetic patients below and above 60 years (Fig. 1). We did find that VWF propeptide (Fig. 2), VWF activation factor (Fig. 3) and total active VWF (Fig. 4) were significantly elevated in diabetic patients >60 years of age in comparison to their controls (P = 0.004, P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively) and diabetic patients below 60 years of age (P = 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively). In addition, we found that the total active VWF was also increased in younger diabetic patients in comparison to their corresponding controls (P < 0.05, Fig. 4). Because the number of patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease was relatively low in our patient population (Table 1), no significant difference in VWF-related parameters could be observed between patients with or without hypertension and with or without coronary artery disease (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

VWF antigen in type 2 diabetes patients and controls, which were divided by age below and above 60 years of age. Individual values of the VWF antigen are shown as closed circle for patients or controls. Bars represent the means of each group (in nanomolar)

Fig. 2.

VWF propeptide in type 2 diabetes patients and controls, which were divided by age below and above 60 years of age. Individual values of the VWF propeptide are shown as closed circle for patients or controls. Bars represent the means of each group (in nanomolar); note the statistic differences in scale between the respective groups. The image analyses were performed with Graph Pad Instat software, version 4.00 (San Diego, CA, USA)

Fig. 3.

VWF activation factor in type 2 diabetes patients and controls, which were divided by age below and above 60 years of age. Individual values of the VWF activation factor are shown as closed circle for patients or controls. The VWF activation factor was calculated by dividing the absorbance slope of a patient sample to the slope of the corresponding standard sample. And the VWF activation factor as a percentage of active VWF is described per micrograms per millilitre VWF antigen. Bars represent the means of each group; note the statistic differences in scale between the respective groups. The graphics was made by GraphPad and Instat software (San Diego, CA, USA)

Fig. 4.

The total active VWF in type 2 diabetes patients and controls, which were divided by age below and above 60 years of age. Individual values of the total active VWF are shown as closed circle for patients or controls. Total active VWF was calculated by multiplying the VWF activation factor with the VWF antigen levels. NPP was set at 100%. The NPP contained 48 nM VWF antigen and 6.3 nM of VWF propeptide. Bars represent the means of each group; note the statistic differences in scale between the respective groups. The graphics was made by GraphPad and Instat software (San Diego, CA, USA)

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

Type 2 diabetic patients older than 60 years of age had increased levels of total active VWF, VWF activation factor and VWF propeptide compared to younger patients and controls. We also found that the total active VWF was associated with the time of being diagnosed with diabetes, indicating that probably the total active VWF is the best marker in this patient population for endothelial activation and endothelial damage. The increased incidence of vascular complications in patients above 60 years aging is probably reflected by increased levels of the VWF parameters measured. This is in line with previous studies which showed that the active quality of VWF is increased in various severely ill patient populations suffering from thrombocytopenia, thrombotic complications or both (Groot et al. 2007; de Mast et al. 2009; Hollestelle et al. 2010; Jezovnik and Poredos 2010).

One of the limitations in this study is the limited number of diabetic patients with vascular disease (Table 1), and this perhaps could explain why we did not observe any association between the VWF-related parameters and vascular disease in aging diabetic patients (data not shown). Furthermore, the number of female controls above 60 years is lower, although not significant, compared to the patients above 60 years. Larger studies are needed to confirm our findings.

All parameters correlated positively with age in patients. In contrast, VWF antigen and total active VWF correlated positively with age in the controls only. This is in agreement with results found in previous studies showing increased VWF levels are associated with age (Gill et al. 1987; Coppola et al. 2003; Favaloro et al. 2005). Next to age, also the period of having diabetes correlated with VWF propeptide and total active VWF, indicating that the duration of the diabetic process influences the endothelium and thereby promotes VWF secretion. When patients and controls were not subdivided by age, we observed a significant difference for VWF antigen between patients and controls (P = 0.018), similar to previous results found in literature (van Mourik et al. 1999; Vischer et al. 1998). However, when the patients and controls were divided by age below and above 60 years of age, VWF antigen levels were not significantly different between the patients and the controls. Probably, we did not find the difference between the subgroups due to the known large variation of VWF antigen levels and smaller size of the groups. Previously, it was shown that VWF is an independent risk factor for the incidence of diabetes (Meigs et al. 2006). Our study shows that the difference for additional VWF-related parameters in patients and controls were more pronounced in type 2 diabetic patients above 60 years of age. Furthermore, no correlation was observed between an inflammation marker, like pulmonary surfactant protein D, and any of the VWF parameters (data not shown).

Together, our data demonstrate that endothelial cell activation and the release of active VWF could be key features of aging type 2 diabetic patients, in particular in patients above 60 years of age. From our data, it has become clear that the “active quality” of VWF is more important than the quantity. The current work could be of high interest because it provides indications that the active quality of VWF plays a significant role in the diabetic disease during the development in age and could be of help in designing new therapeutic strategies against the diabetic complications. Furthermore, potential implications of our results could be to get better insigne which patients are at risk of extra thrombosis complications due to high active VWF levels, as especially was observed in patients above 60 years.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Lenting (UMC Utrecht, The Netherlands) for his advice. This work was partly supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant #2006B010; Peter J. Lenting) (grant 2006T053; Bas de Laat) and supported by the Nature Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (grant Z2008C09) and National Science and Technology Supporting Item (2006BAI01A13), China. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or in preparation of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Shuang Feng Chen, Zuo Li Xia, Ji Ju Han, Yi Ting Wang, Ji Yue Wang, Shao Dong Pan, and Ya Ping Wu contributed equally to this manuscript.

The institutional review board of Liaocheng School of Clinical Medicine, Taishan Medical University approved this article.

References

- Blann AD. Plasma von Willebrand factor, thrombosis, and the endothelium: the first 30 years. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola R, Mari D, Lattuada A, Franceschi C. Von Willebrand factor in Italian centenarians. Haematologica. 2003;88:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mast Q, Groot E, Asih PB, Syafruddin D, Oosting M, Sebastian S, Ferwerda B, Netea MG, de Groot PG, van der Ven AJ, Fijnheer R. ADAMTS13 deficiency with elevated levels of ultra-large and active von Willebrand factor in P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:492–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ediger MN, Olson BP, Maynard JD. Noninvasive optical screening for diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:776–780. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaloro EJ, Soltani S, McDonald J, Grezchnik E, Easton L, Favaloro JW. Reassessment of ABO blood group, sex, and age on laboratory parameters used to diagnose von Willebrand disorder: potential influence on the diagnosis vs the potential association with risk of thrombosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:910–917. doi: 10.1309/W76QF806CE80CL2T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel DS, Meigs JB, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, O'Donnell CJ, D'Agostino RB, Tofler GH. Von Willebrand factor, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and risk of cardiovascular disease: the framingham offspring study. Circulation. 2008;118:2533–2539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.792986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill JC, Endres-Brooks J, Bauer PJ, Marks WJ, Jr, Montgomery RR. The effect of ABO blood group on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 1987;69:1691–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot E, de Groot PG, Fijnheer R, Lenting PJ. The presence of active von Willebrand factor under various pathological conditions. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;214:284–289. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3280dce531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollestelle MJ, Donkor C, Mantey EA, Chakravorty SJ, Craig A, Akoto AO, O'Donnell J, van Mourik JA, Bunn J. von Willebrand factor propeptide in malaria: evidence of acute endothelial cell activation. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollestelle MJ, Sprong T, Bovenschen N, de Mast Q, van der Ven AJ, Joosten LA, Neeleman C, Hyseni A, Lenting PJ, de Groot PG, van Deuren M. Von Willebrand factor activation, granzyme-B and thrombocytopenia in meningococcal disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1098–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulstein JJ, de Groot PG, Silence K, Veyradier A, FijnheerR LPJ. A novel nanobody that detects the gain-of-function phenotype of von Willebrand factor in ADAMTS13 deficiency and von Willebrand disease type 2B. Blood. 2005;106:3035–3042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezovnik MK, Poredos P. Idiopathic venous thrombosis is related to systemic inflammatory response and to increased levels of circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction. Int Angiol. 2010;29:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs JB, O'Donnell CJ, Tofler GH, Benjamin EJ, Fox CS, Lipinska I, Nathan DM, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW. Hemostatic markers of endothelial dysfunction and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2006;55:530–537. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natali A, Toschi E, Baldeweg S, CiociaroD FS, Sacca L, Ferrannini E. Clustering of insulin resistance with vascular dysfunction and low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:1133–1140. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri ZM. Structure and function of von Willebrand factor. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:576–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler JE. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mourik JA, Boertjes R, Huisveld IA, Fijnvandraat K, Pajkrt D, van Genderen PJ, Fijnheer R. von Willebrand factor propeptide in vascular disorders: a tool to distinguish between acute and chronic endothelial cell perturbation. Blood. 1999;94:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schooten CJ, Denis CV, Lisman T, Eikenboom JC, Leebeek FW, Goudemand J, Fressinaud E, van den Berg HM, de Groot PG, Lenting PJ. Variations in glycosylation of von Willebrand factor with O-linked sialylated T antigen are associated with its plasma levels. Blood. 2007;109:2430–2437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-032706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer UM. von Willebrand factor, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1186–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer UM, Emeis JJ, Bilo HJ, Stehouwer CD, Thomsen C, Rasmussen O, Hermansen K, Wollheim CB, Ingerslev J. von Willebrand factor (vWf) as a plasma marker of endothelial activation in diabetes: improved reliability with parallel determination of the vWf propeptide (vWf:AgII) Thromb Haemost. 1998;80:1002–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD, Fay PJ, Sporn LA, Sinha S, Lawrence SO, Marder VJ. Divergent fates of von Willebrand factor and its propolypeptide (von Willebrand antigen II) after secretion from endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;8:1955–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]