Abstract

The ability of the endothelium to produce nitric oxide, which induces generation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) that activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG-I), in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), is essential for the maintenance of vascular homeostasis. Yet, disturbance of this nitric oxide/cGMP/PKG-I pathway has been shown to play an important role in many cardiovascular diseases. In the last two decades, in vitro and in vivo models of vascular injury have shown that PKG-I is suppressed following nitric oxide, cGMP, cytokine, and growth factor stimulation. The molecular basis for these changes in PKG-I expression is still poorly understood, and they are likely to be mediated by a number of processes, including changes in gene transcription, mRNA stability, protein synthesis, or protein degradation. Emerging studies have begun to define mechanisms responsible for changes in PKG-I expression and have identified cis- and trans-acting regulatory elements, with a plausible role being attributed to post-translational control of PKG-I protein levels. This review will focus mainly on recent advances in understanding of the regulation of PKG-I expression in VSMCs, with an emphasis on the physiological and pathological significance of PKG-I down-regulation in VSMCs in certain circumstances.

Keywords: cGMP-dependent protein kinase, Gene, mRNA stability, Regulation, Transcription, Vascular smooth muscle cells, Ubiquitination, Post-transcription

1. PKG-I and the vasculature

Nitric oxide (NO) signalling plays a pivotal role in the normal physiology of the vasculature. NO, generated by different nitric oxide synthase isoforms (eNOS, nNOS and iNOS), activates soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) to produce variable amounts of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) depending on the NOS isoform involved. cGMP can be also synthesized following activation of particulate guanylyl cyclase by natriuretic peptides. These cyclases differ in their intracellular distribution, with sGC being described as a cytosolic protein and particulate guanylyl cyclase being a membrane-bound protein. The downstream effectors of cGMP include cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG-I),1,2 cGMP-modulated ion channels,3 and phosphodiesterases.4 The physiological relevance of PKG-I in the vascular system was demonstrated following studies using PKG-I-deficient mice.5–8 In these mice, the loss of PKG-I not only abolished relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in response to NO/cGMP, but severely altered vascular, kidney, cardiac, and intestinal functions.5,8

In addition to its vasodilator effect, NO/cGMP has been revealed to have beneficial roles within the vessel wall, including inhibition of VSMC proliferation,9,10 reduction of platelet aggregation,11 apoptosis,10 and gene regulation.12–18 These effects are mediated by PKG-I activation. PKG-I is a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase that is activated by the NO/sGC/cGMP system. PKG-I belongs to the family of serine/threonine kinases that are present in a variety of eukaryotes ranging from unicellular organisms to Homo sapiens. PKG-I exists in two isoforms, PKG-1α and PKG-1β, which are expressed and active in different types of cells and tissues,19,20 with predominance of one isoform over another. PKG-I is expressed at high levels in VSMCs (both PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ) and platelets (PKG-Iβ), and at lower levels in endothelial cells (PKG-Iβ) and cardiomyocytes (PKG-Iα). The reason for the differential distribution of PKG-I isoforms in cells is unknown; however, It is noteworthy that PKG-I expression is reduced or even lost in many primary cultured and passaged cells (VSMCs and endothelial cells),21,22 as well as in numerous cell lines. PKG-I is involved in many cell functions, such as relaxation, platelet aggregation, remodelling, hypertrophy, apoptosis, differentiation, neuronal plasticity, and erectile dysfunction.23–29 Functionally, PKG phosphorylates several substrates7,23,30 and interacts, by engaging its N-terminal, with numerous proteins. Both isoforms appear to have specific preferences for interaction with target substrate proteins. For instance, PKG-1α interacts specifically with the myosin-interacting subunit of myosin phosphatase 1 and regulator of G-protein signalling 2, while PKG-1β interacts with inositol triphosphate (IP3) receptor-associated cGMP kinase substrate (reviewed by Francis et al.).23

In the vascular system, PKG-I mediates vascular tone, as well as VSMC proliferation and differentiation. In vascular endothelial cells, PKG-I regulates cell motility, migration, and proliferation. These functions are reported to be essential for vascular permeability and angiogenesis. In cardiac myocytes, PKG-I negatively modulates contractility and hypertrophy, as well as mediating apoptosis.31 Given that PKG is needed to accomplish multiple cellular functions, its dysregulation has been incriminated in many diseases, such as hypertension (systemic and pulmonary), atherosclerosis, chronic heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular remodelling, ischaemia/reperfusion injury, diabetes, and cancer. Accumulating evidence suggests that cGMP/PKG signalling plays a cardioprotective role against various cardiovascular pathologies. In vivo animal experiments are supporting this role and are providing models for testing the therapeutic potential of the cGMP/PKG pathway. Indeed, ongoing clinical trials, specifically using phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, are aiming to develop therapies for systemic hypertension, cardiac failure, cardiac reperfusion injury, VSMC proliferation, atherogenesis, and endothelial dysfunction.5,6,31–36

Recent studies have established that many stimuli, as well as many pathological situations, contribute to the modulation of PKG-I mRNA and protein expression. These effects on PKG-I occur in VSMCs from different vascular beds, both in vitro and in vivo (Table 1). It is of importance that most of these stimuli have been implicated in vascular pathophysiology. They include growth factors, cytokines, and inflammatory mediators, such as lipopolysaccharides. In most of these situations, a large increase in cGMP levels followed by sustained activation of PKG-I leads to a suppression of its expression via negative feedback control. Despite advanced knowledge concerning PKG function,37–40 little is known about the molecular mechanism governing its expression. Few studies have provided a detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of PKG-I expression. \

Table 1.

Situations where PKG-I mRNA and/or protein were suppressed in different cells, tissues, or organs

| First author | Cells/organ | Protein | mRNA | Stimulus/situation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamura et al. | Rat/human VSMCs (aorta) | ND | + | Mitogenes (PDGF-BB, Ang II, TGF-β TNF-α) | 19 |

| Wollert et al. | Cardiomyocytes | + | ND | cGMP analogues | 35 |

| Browner et al. | Bovine VSMCs (aorta) | + | + | cGMP/cAMP analogues, IL-1, LPS, TNF-α | 74 |

| Dey et al. | Rat/mouse VSMCs (aorta)/COS7 | + | ND | cGMP analogues, NO donors | 78 |

| Melichar et al. Sinnaeve et al. |

Aortic homogenate, neointima Carotid arteries |

ND + |

+ ND |

Atherosclerosis In-stent restenosis |

84

85 |

| Dou et al. | Porcine coronary arteries | + | + | NO donors, cGMP analogues | 96 |

| Zhuang et al. | Rat VSMCs (aorta) | + | + | PDGF, NO donors | 97 |

| Soff et al. | Rat/mouse VSMCs (aorta) | + | + | Nitrovasodilators, cGMP/cAMP analogues | 98 |

| Jacob et al. | Rabbit urinary bladder | + | + | Diabetes | 99 |

| Li et al. Anderson et al. |

Neointimal VSMCs (carotid artery) | + + |

ND ND |

Intimal thickening/carotid artery Ballon injury/coronary artery |

100 101 |

| Resnik et al. | VSMCs from normal/hypertensive fetal lambs (pulmonary artery) | + | + | Hypoxia | 102 |

| Lin et al. | VSMCs of old/young rats (aorta) | + | ND | Age | 103 |

| Yamashita et al. | Aorta extracts | + | ND | Mouse overexpressing eNOS | 104 |

| Chang et al. | Corpus cavernosum smooth muscle | + | + | Diabetes | 105 |

| Perkins et al. | Porcine pulmonary artery | + | + | NO donors, cGMP analogues | 106 |

| Bachiller et al. | Mouse pup lung VSMCs (pulmonary vein) | + | + | TGF-β | 107 |

| Gao et al. | Lamb fetal pulmonary veins | + | + | Hypoxia | 108 |

| Ruetten et al. | Aortic rings | ND | + | Hypertensive rats | 109 |

| Li et al. | Kidney | + | + | Ischaemia/reperfusion | 110 |

| Zhou et al. | Ovine fetal pulmonary veins | + | ND | Hypoxia | 111 |

| Liu et al. | Rat VSMCs (aorta) | + | + | High glucose | 112 |

| Wang & Li | Primary rat/mouse VSMCs (aorta) | + | ND | High glucose | 113 |

Abbreviations: Ang II, angiotensin II; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ND, not determined; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; COS7, monkey fibroblast cell line.

This review will mainly focus on what has been learned about the molecular mechanisms governing the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of PKG-I in VSMCs. We will provide a discussion of the physiological and pathophysiological significance of the modulation of PKG-I expression.

2. PKG-I gene

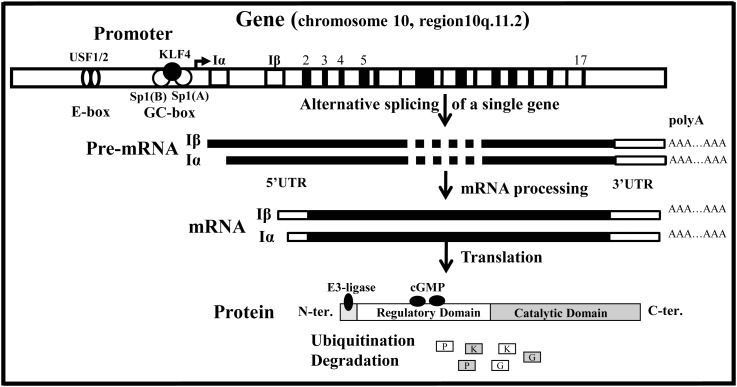

Mammals possess two PKG genes, prkg1 and prkg2, which encode for PKG-I and PKG-II proteins, respectively. The prkg1 gene, which is the only one expressed in smooth muscle, is a single-copy gene consisting of 19 exons encompassing at least 1.3 Mbp assigned to chromosome 10, region 10q11.2.19,41–43 The first two exons of human prkg1, (α and β) have been identified, and cDNAs encoding PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ have been cloned from different tissues,41,44,45 while the remaining 17 exons are common between the two isoforms. Southern/northern blot analysis suggested that human PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ are generated by alternative splicing of a single gene.46 The two isoforms differ only in the N-terminal dimerization domain of the protein.47 Using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends, potential sites for initiation of transcription were identified 5′ upstream of both PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ exons. Northern blot analysis demonstrated distinct patterns of distribution of these two isoforms in cells and tissues.48

3. Transcriptional regulation of PKG-I

The PKG-I promoter has been cloned from different species.19,48 Like many of the so-called constitutively expressed proteins, the PKG-I promoter lacks a typical TATA box and CCAT box, but harbours multiple potential cis-regulatory DNA consensus sequences, including Sp1 sites, upstream stimulatory factor 1/2 (USF1/2), zinc-finger-type Krüppel-like transcriptional factor (KLF4), and probably other unidentified elements. A dissection of the human PKG-I proximal core promoter revealed the presence of regulatory regions involved in basal PKG-I transcription.49 Regulatory domain I (RDI, from −120 to +1 bp relative to transcription initiation) corresponds to high-affinity Sp1 transcription factor recognition sites (Sp1A and Sp1B; Figure 1). This domain was found to bind Sp1 and Sp3, but not Sp2, as demonstrated by gel shift assays.49 The regulatory domain II (RDII, from −591 to −473 bp) binds USF1/2,50 and most probably other unidentified transcription factors. Site-directed mutagenesis of the E-boxes abolished the binding of USF1/2 proteins and decreased the luciferase activity of the PKG-I −591 bp promoter, thus confirming the involvement of these transcription factors in mediating gene expression. In addition, cotransfection experiments demonstrated that overexpression of USF1/2 increased PKG-I promoter activity.50

Figure 1.

Structural organization of prkg1 and the corresponding mRNA(s) and proteins. The characterization of the human prkg1 has revealed that the transcription unit of 19 exons and 18 introns spans a region greater than 1.3 Mbp on chromosome 10 at region 10q11.2. The PKG-I promoter is transcriptionally controlled by upstream stimulatory factor 1/2 (USF1/2), Sp1(A), Sp1(B), and Krüppel-like transcriptional factor (KLF4). The PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ isoforms are generated by alternative splicing of a single gene and possess similar 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs), while differing in their 5′UTRs. These transcripts are translated to PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ, which differ only in the first 100 amino acids within the N-terminal domain.

PKG-I expression was reported to be controlled by RhoA and Rac1 activities.51 RhoA and Rac1 have opposing effects on PKG-I expression, with RhoA suppressing and Rac1 activating its promoter. RhoA regulation of the PKG-Iα promoter is mediated, at least in part, through binding of KLF4 to Sp1 consensus sites in the proximal promoter, which is located within the two Sp1 sites.51 Zeng et al. found that the Sp1(A) site, at the transcription start, is the most important, with the other site contributing to maximal transcriptional effects of RhoA. The sequence of the Sp1(A) site resembles the major Rho-regulated Sp1 site of the p21Cip1/Waf1 promoter, whereas the other putative Sp1 sites in the PKG-I promoter have slightly different sequences.19,52 In an electrophoretic mobility shift assay using a probe corresponding to the combined Sp1(A) and (B) sites encompassing two juxtaposed Sp-binding sites within the PKG-I promoter, the authors obtained a single major protein–DNA complex that contained KLF4. The authors could not rule out the existence of a tight co-operation of KLF4 with other transacting factors. In addition, the complex did not contain detectable amounts of Sp1 or Sp3 despite a long autoradiograph exposure. This contrasted with a previously reported electrophoretic mobility shift assay study on PKG-I promoter, where single Sp1(A) or Sp1(B) sequences showed a net Sp1 and Sp3 binding.49 The reason for this discrepancy is not known; however, the nature of the probes used [single Sp1(A) or Sp1(B)49 vs. double Sp1(A-B)]51 might explain this difference. Also, it is not surprising that a competition between Sp1/Sp3 and KLF4 in transcriptional regulation might occur and contribute to this discrepancy.53 Although PKG-I expression is down-regulated by RhoA and up-regulated by Rac1, it is not known whether these processes are involved in producing a prolonged elevation of cGMP via expression of iNOS, for instance. It is, however, important to mention that a significant role was attributed to PKG-I in the regulation of Rac1 and RhoA activities.54–56 Thus, it is tempting to speculate, as previously suggested, that reduction of PKG-I expression by RhoA may explain the decreased PKG-I levels in VSMCs found in some models of hypertension and vascular injury.51

It is well known that the FoxO family of transcription factors (FoxO1a, FoxO3, and FoxO4a) regulates diverse cellular responses, including apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, differentiation, DNA repair, and oxidative stress. The transcriptional factor FoxO1a was reported to activate PKG-I expression directly during myoblast fusion.57 The regions containing the FoxO1a binding sites (−7.0 to −6.7 kb and +6.5 to +6.8 kb) surround the PKG-Iα exon 1.57 Upon muscle cell differentiation, FoxO1a directly activates PKG-I transcription. This FoxO1a activity is required in initiating, but not sustaining, PKG-I expression during myoblast differentiation. Mechanistically, PKG-I is acting as a feedback loop, not only by phosphorylating FoxO1a and abolishing its DNA binding activity to consensus elements, but also by expelling it from the nucleus. This negative transcription regulation of FoxO1a by PKG-I results in controlling proper fusion and muscle differentiation.57 Interestingly, FoxO1a transcription factor was reported to be regulated by NO/cGMP,58 mediators that are known to affect PKG-I mRNA and protein levels in many situations.

Owing to the multiple actions of PKG-I in many cell and tissue types, it is likely that several factors would contribute to the regulation of its expression. A recent study demonstrated that the tumour suppressor p53 induces PKG-I mRNA and protein expression in PC12 cells.59 The p53 tumour suppressor protein was shown to drive the expression of PKG-I required for counteracting growth cone collapse. Mechanistically, p53 contributes to PKG-I up-regulation through binding to specific consensus elements on several introns, common to both PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ isoforms, of the PKG-I mouse gene.60,61 Interestingly, the PKG-I gene was found to contain two high-scored p53 consensus binding sites (half-sites) within 1125 bp upstream of its transcription start site.61 Activation of p53 resulted in an increase of PKG-I promoter activity, assayed by luciferase reporter analysis, along with the up-regulation of PKG-I mRNA, simulating transcription regulation.61 Using chromatin immunoprecipitation assay and electrophoretic mobility shift assay, the authors demonstrated that p53 binds and interacts with p53 cis-elements within the promoter.

In light of the modulation of PKG-I expression by all of the above-mentioned factors, it is of importance to highlight that Sp1/Sp3, KLF4, p53, FoxO1, USF1/2, and RhoA expression and activity were reported to be regulated by NO/cyclic nucleotides.58,62–66 However, the existence of a direct relation between the effect of the NO/cyclic nucleotide pathway on these transcription factors and PKG-I expression has not yet been demonstrated. In addition, the regulation of gene expression by PKG-I downstream of cGMP elevation is an emerging area of interest. Indeed, PKG-I has been shown to regulate the activity of many transcription factors, including cAMP-response element binding protein, transcription factor II-I, activator protein 1, early growth response protein 1, and nuclear factor-kappa B in different cell types.12–18,67–71 However, it is not known whether these transcription factors are also involved in modulating PKG-I expression.

4. Post-transcriptional regulation

The alteration in mRNA stability and translation efficiency is often considered as key mediator of post-transcriptional regulation.72 The reason for studying the importance of post-transcriptional regulation of PKG-I may relate to the finding that its mRNA has a relative long half-life at baseline (10–12 h).73 In addition, an examination of the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) mRNA of PKG-I revealed the presence of multiple copies of adenylate- and uridylate-rich elements composed of the sequence 5′-AUUUA-3′ and 5′-AUUUUA-3′. These 3′UTRs are potential sites of interaction with specific RNA-binding proteins important for the destiny of PKG-I mRNA.

The level of PKG-I mRNA in the cell is very low. Using real-time PCR, it has been estimated that the levels of PKG-I mRNA in primary cultures of bovine aortic smooth muscle cells are approximately 1000–2000 copies per cell.74 In fact, northern blot analysis of PKG-I mRNA expression is exceedingly difficult to accomplish owing to the low copy number. However, it is not known whether a post-transcriptional mechanism might affect PKG mRNA levels through cis-acting RNA elements located in the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) and 3′UTR of PKG-I.

4.1. Contribution of 5′UTR mRNA

It is well established that PKG-I undergoes alternative splicing to generate isoform Iα or Iβ,19,45–48 which both possess the same 3′UTR mRNA sequence but have different 5′UTRs located upstream of the two first exons coding for PKG-Iα or PKG-Iβ. In an unpublished study (Sellak H, CS Choi, TM Lincoln unpublished observations), we explored the possible involvement of the 5′UTR in the regulation of luciferase reporter vector. For this purpose, 5'UTR sequences related to PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ were cloned and inserted upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. The 5′UTR of PKG-Iα induced stronger luciferase activity compared with the 5′UTR of PKG-Iβ. The precise mechanism by which 5′UTR PKG-Iα increased luciferase activity was not established; however, it is possible that the size (40 nucleotides for PKG-Iα, and 267 nucleotides for PKG-Iβ)19 as well as the secondary structure adopted by these mRNA regions may account for this difference.

4.2. Contribution of 3′UTR mRNA

The rationale for exploring the involvement of 3′UTR mRNA in PKG-I regulation emerged from previous studies suggesting that the PKG-I proximal promoter contained few consensus elements (USF1/2, Sp1/3, and KLF4) to account for PKG-I expression.19,49–51 An examination of the PKG-I 3′UTR mRNA sequence revealed the presence of several adenylate- and uridylate-rich regions, which might play a significant role in stabilizing or destabilizing PKG-I mRNA. The 3′UTR mRNA contains two AUUUA and two AUUUUA sequences, in addition to a potential polyadenylated signal.73 These regions were found to be highly conserved across human, bovine, chimpanzee, and murine species by analysing sequence homology between species. This conservation of these elements between species is itself of interest because it may suggest the existence of a common mechanism governing post-transcriptional regulation of PKG-I through its 3′UTR mRNA.

The individual adenylate- and uridylate-rich regions as well as the 3′UTR mRNA generated by in vitro transcription were able to bind to cytosolic and nuclear proteins having molecular weights ranging from 35 to 55 kDa.73 In addition, the 3′UTR of the PKG-I mRNA possesses potent stabilizing activity, as tested by luciferase reporter assays. The study did not exclude other possibilities contributing to this stability, such as translational efficiency and cap structure located at the 5′UTR. On the contrary, the results indicated that different repertoires of unidentified RNA-binding proteins target the PKG-I 3′UTR to regulate PKG-I mRNA stability and, thus, alter PKG-I expression.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that microRNAs play an important role in gene regulation. To the best of our knowledge, however, there is no information regarding the potential role of microRNAs in the modulation of PKG-I expression. Recently, we scanned the PKG 3′UTR mRNA using TargetScanHuman 6.2 software for prediction of microRNA targets. The result showed that several microRNAs might be potential candidates for the regulation of PKG-I expression (miR103/107/15abc/16/195/218/181abcd/ 322/424/497/1987…etc); however, there is no experimental evidence to support this assumption.

5. Post-translational regulation of PKG-I

The half-life of the PKG-I protein can be viewed as very long or as rather short. For example, platelets express very high levels of the PKG-Iβ isoform (not PKG-Iα), and they possess no nucleus, no mRNA, and circulate for up to 60 days. In contrast, the half-life of PKG-I protein in VSMCs can be only 24 h, and this appears to be affected by inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which are reported to promote modulation of VSMCs to the proliferative synthetic phenotype.75 The regulation of PKG-I mRNA turnover is not the only mechanism by which PKG-I (at least the PKG-Iα isoform) is regulated in VSMCs. It is known that activation of the NO/cGMP pathway can lead to a sustained activation of PKG-I. Thus, like protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase degradation by phorbol myristate acetate and cAMP, respectively,76,77 sustained activation of PKG-I may be followed by its more long-term down-regulation. This results in autophosphorylation of the autoinhibitory domain, a concept that is well described in the literature, leading to down-regulation of PKG-I expression.78 Moreover, in response to sustained activation/autophosphorylation, it was hypothesized that PKG-I becomes ubiquitinated and degraded. This down-regulation occurs even in cells where total mRNA synthesis is inhibited as well as in cells that do not express endogenous PKG-I mRNA or protein (COS7).78 Further investigations determined that PKG-I is subjected to ubiquitination following incubation with 8-bromo-cGMP and that serine 64 (Ser64) of PKG-Iα appears to be the autophosphorylation site that targets E3 ligase binding and ubiquitination. Likewise, Ser64 is reported to be the key site that promotes prolonged activation of PKG-Iα.79 This down-regulation of PKG-Iα protein occurs after chronic activation in murine aortic smooth muscle cells by the cGMP analogue in normoxic conditions.78,80 Recently, another report has demonstrated that hypoxia rapidly induces the conjugation of multiple ubiquitin molecules to PKG-I protein, leading to an enhanced accumulation of ubiquitinated PKG-I, which affects its ligand affinity.81 This accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated PKG-I induced by hypoxia is not affected by the endogenous activation of PKG-I by a cGMP analogue, or by the endogenous inhibition of PKG-I activity via a cell-permeable inhibitor. Although these described mechanisms of PKG-I regulation at the post-translational level are different, the outcome is similar, because they both lead to alteration of the NO/cGMP response in VSMCs.

As mentioned above, PKG-I isoforms undergo autophosphorylation.82,83 At least five and two autophosphorylated residues have been identified in PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ, respectively. Further investigations have demonstrated that autophosphorylation of Ser64 is involved in the activation of PKG-Iα79; likewise, autophosphorylation of Ser79 activates PKG-Iβ.82 Given that the N-terminal autoinhibitory domain differs between PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ, it was suggested that autophosphorylation may account for the different sensitivity of the two isoforms to cGMP, in addition to mediating the binding of partner proteins. Consequently, at least one common role for the autophosphorylation of the autoinhibitory domain is to participate in the activation process. Alternatively, in certain conditions, autophosphorylation of PKG-Iα at Ser64 may account for a negative feedback regulation by promoting the kinase ubiquitination and degradation, because mutation of Ser64 to alanine did not cause degradation of PKG-Iα.78

It is interesting to underline the difference between the behaviour of the PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ isoforms in response to NO/cGMP-dependent ubiquitination. It was found that the PKG-Iα isoform is more sensitive to ubiquitination compared with the PKG-Iβ isoform. The latter has a different autophosphorylation/autoinhibitory domain from the PKG-Iα isoform.78 It is believed that this type of regulation might dictate the destiny of the two isoforms in a particular cell.

6. Significance of PKG-I suppression

PKG-I is involved in many diseases,5–8,27–29 including vasculoproliferative disorders, such as restenosis and atherosclerosis.84,85 A key process in vascular remodelling is the phenotypic modulation of VSMCs from contractile to proliferating/synthetic (dedifferentiated) cells.86,87 In addition, vascular diseases are known to be mediated by inflammatory mediators that activate growth and dedifferentiation programmes in VSMCs.88,89 In these situations, tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, transforming growth factor-β, and lipopolysaccharides stimulate VSMCs proliferation and promote phenotypic modulation. These effects are enhanced in the presence of growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor, that activate tyrosine kinase receptors in VSMCs.90–92 The inflammatory response may be initiated by injury as well as by a wide variety of other risk factors associated with atherosclerosis, stroke, and cardiovascular disorders. It is interesting that the PKG-Iα isoform, in contrast to the PKG-Iβ isoform, exists as a partially active form that does not require an elevation in cGMP.93 As previously suggested, PKG-Iα may serve to maintain differentiated characteristics of VSMCs in the absence of cGMP elevation. Thus, PKG-Iα, in particular, would be susceptible to down-regulation upon sustained elevations of NO/cGMP. This observation has a pathophysiological significance, because cytokines, by inducing iNOS expression, increase cGMP to high and persistent levels, leading to PKG-Iα down-regulation and cell dedifferentiation, if only temporarily, to accomplish wound-healing functions through proliferation and fibrotic activity.13 Unfortunately, this key mechanism to allow repair of vascular injury may also lead to progression of vascular diseases.86

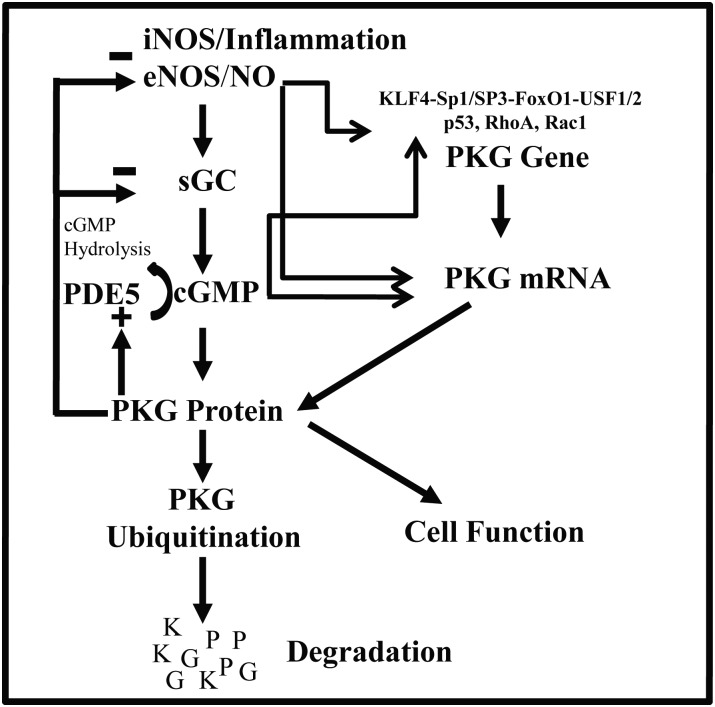

Suppression of PKG-I through mRNA and/or protein degradation might be the outcome of cell adaptation to avoid PKG-I hyperactivation and, ultimately, substrate hyperphosphorylation. It is also possible that activation of phosphodiesterase 5 in response to sustained increases in the NO/cGMP/PKG-I signalling pathway may result in a classic feedback response to blunt or terminate a signal leading to a long-lasting reduction of cGMP content. Alternatively, in pathological situations, sustained release of NO induces hyperactivation of PKG-I. Hence, a negative feedback will be initiated by PKG-I, or inflammatory mediators, resulting in termination of eNOS/sGC activities,94,95 in addition to resulting in its own degradation (Figure 2).78,80

Figure 2.

Regulation of PKG-I expression. In physiological situations, cGMP released following soluble guanylyl cylase (sGC) activation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-generated NO leads to PKG-I stimulation, and results in normal cellular function. In pathological situations, in contrast, excessive cGMP production in response to iNOS expression leads to sustained activation of PKG-I, which results in its own degradation by ubiquitination. Also, PKG-I suppresses eNOS/sGC and activates phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5). This negative feedback control represents an adaptation of cells to higher concentrations of cGMP. One scenario in this type of regulation is the possibility of two mechanisms contributing to PKG-I suppression, with one occurring rapidly at the post-translational level and resulting in PKG-I ubiquitination, and one more slowly, resulting in a decrease of PKG-I mRNA.

7. Conclusion and perspectives

While PKG-I was demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of numerous cellular functions, its deregulation can lead to many cardiovascular diseases. Although the literature contains an abundance of pathophysiological situations in which PKG-I (protein and/or mRNA) expression is suppressed (Table 1), the molecular mechanisms governing this decrease are not fully understood. Few groups have attempted to dissect this pathway, and emerging data will provide more details about the mechanism of PKG expression. From what we have learned so far, PKG suppression seams to occur predominantly at the post-translational level.

Although the molecular mechanisms contributing to PKG-I gene expression are gradually emerging, many details regarding its transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation are still unknown. However, an examination of the correlation between changes in PKG-I activity along with the PKG-I mRNA concentration, as well as protein expression (Iα isoform vs. Iβ), in normal and pathological situations, will advance our knowledge of PKG-I function in the cardiovascular system. In addition, understanding of the mechanism of PKG-I expression will open the search for improved new therapies for cardiovascular diseases. Indeed, accumulating evidence, using in vivo animal models, is demonstrating this and providing pharmacological tools to test the therapeutic potential of the cGMP/PKG-I pathway in systemic and pulmonary hypertension, cardiac failure, cardiac reperfusion injury, atherogenesis, endothelial dysfunction, and many other diseases.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant HL066164.

References

- 1.Lincoln TM, Hall CL, Park CR, Corbin JD. Guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate binding proteins in rat tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2559–2563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2559. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.8.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo JF, Kuo WN, Shoji M, Davis CW, Seery VL, Donnelly TE., Jr Purification and general properties of guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from guinea pig fetal lung. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1759–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Light DB, Corbin JD, Stanton BA. Dual ion-channel regulation by cyclic GMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Nature. 1990;344:336–339. doi: 10.1038/344336a0. doi:10.1038/344336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beavo JA, Hardman JG, Sutherland EW. Hydrolysis of cyclic guanosine and adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphates by rat and bovine tissues. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5649–5655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeifer A, Klatt P, Massberg S, Ny L, Sausbier M, Hirneiss C, et al. Defective smooth muscle regulation in cGMP kinase I-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1998;11:3045–3051. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3045. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.11.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feil R, Lohmann SM, de Jonge H, Walter U, Hofmann F. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases and the cardiovascular system: insights from genetically modified mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:907–916. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100390.68771.CC. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000100390.68771.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann F, Feil R, Kleppisch T, Schlossmann J. Function of cGMP-dependent protein kinases as revealed by gene deletion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1–23. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2005. doi:10.1152/physrev.00015.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao YD, Cai L, Mirza MK, Huang X, Geenen DL, Zhao YY. Protein kinase G-I deficiency induces pulmonary hypertension through Rho A/Rho kinase activation. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2268–2275. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.016. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munzel T, Feil R, Mulsch A, Lohmann SM, Hofmann F, Walter U. Physiology and pathophysiology of vascular signaling controlled by cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation. 2003;108:2172–2183. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094403.78467.C3. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000094403.78467.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiche JD, Schlutsmeyer SM, Bloch DB, de la Monte SM, Roberts JD, Jr, Filippov G, et al. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of cGMP-dependent protein kinase increases the sensitivity of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells to the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of nitric oxide/cGMP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34263–34271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34263. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.51.34263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Xi X, Gu M, Feil R, Ye RD, Eigenthaler M, et al. Stimulatory role for cGMP-dependent protein kinase in platelet activation. Cell. 2003;12:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01254-0. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi C, Sellak H, Brown FM, Lincoln TM. cGMP-dependent protein kinase and the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell gene expression: possible involvement of Elk-1 sumoylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1660–H1670. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2010. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lincoln TM, Wu X, Sellak H, Dey N, Choi CS. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by cyclic GMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Front Biosci. 2006;11:356–367. doi: 10.2741/1803. doi:10.2741/1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilz RB, Casteel DE. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP. Circ Res. 2003;93:1034–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000103311.52853.48. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000103311.52853.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln TM, Dey N, Sellak H. cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling mechanisms in smooth muscle: from the regulation of tone to gene expression. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1421–1430. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idriss SD, Gudi T, Casteel DE, Kharitonov VG, Pilz RB, Boss GR. Nitric oxide regulation of gene transcription via soluble guanylate cyclase and type I cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9489–9493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9489. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.14.9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudi T, Lohmann SM, Pilz RB. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase requires nuclear translocation of the kinase: identification of a nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5244–5254. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haby C, Lisovoski F, Aunis D, Zwiller J. Stimulation of the cyclic GMP pathway by NO induces expression of the immediate early genes c-fos and junB in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 1994;62:496–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020496.x. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura N, Itoh H, Ogawa Y, Nakagawa O, Harada M, Chun TH, et al. cDNA cloning and gene expression of human type Iα cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Hypertension. 1996;27:552–557. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.552. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.27.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo JF. Guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases in mammalian tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4037–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4037. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.10.4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornwell TL, Soff GA, Traynor AE, Lincoln TM. Regulation of the expression of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase by cell density in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res. 1994;31:330–337. doi: 10.1159/000159061. doi:10.1159/000159061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Draijer R, Vaandraager AR, Nolte C, De Jonge HG, Walter U, Van Hinsbergh VWM. Expression of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I and phosphorylation of its substrate, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein, in human endothelial cells of different origin. Circ Res. 1995;77:897–905. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.897. doi:10.1161/01.RES.77.5.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francis SH, Busch JL, Corbin JD, Sibley D. cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:525–563. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002907. doi:10.1124/pr.110.002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlossmann J, Desch M. IRAG and novel PKG targeting in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H672–H682. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00198.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmann F, Bernhard D, Lukowski R, Weinmeister P. cGMP-dependent protein kinase modulators. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:409–421. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_8. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp-Harper B, Schmidt HH. cGMP in the vasculature. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:447–467. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_19. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson K, Pandita RK, Aszodi A, Ahmad M, Pfeifer A, Fassler R, et al. Functional characteristics of urinary tract smooth muscles in mice lacking cGMP protein kinase type I. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1112–R1120. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ny L, Pfeifer A, Aszodi A, Ahmad M, Alm P, Hedlund P, et al. Impaired relaxation of stomach smooth muscle in mice lacking cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:395–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703061. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedlund P, Aszodi A, Pfeifer A, Alm P, Hofmann F, Ahmad M, et al. Erectile dysfunction in cyclic GMP-dependent kinase I-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2349–2354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030419997. doi:10.1073/pnas.030419997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbrügge M, Walter U. Purification of vasodilator regulated phosphoprotein from human platelets. Eur J Biochem. 1989;185:41–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15079.x. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai EJ, Kass DA. Cyclic GMP signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:216–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.009. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kass DA. Cardiac role of cyclic-GMP hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase type 5: from experimental models to clinical trials. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2012;9:192–199. doi: 10.1007/s11897-012-0101-0. doi:10.1007/s11897-012-0101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. PDE5 inhibition with sildenafil improves left ventricular diastolic function, cardiac geometry, and clinical status in patients with stable systolic heart failure: results of a 1-year, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:8–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944694. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landmesser U, Wollert KC, Drexler H. Potential novel pharmacological therapies for myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:519–527. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn317. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvn317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollert KC, Fiedler B, Gambaryan S, Smolenski A, Heineke J, Butt E, et al. Gene transfer of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I enhances the antihypertrophic effects of nitric oxide in cardiomyocytes. Hypertension. 2002;39:87–92. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097292. doi:10.1161/hy1201.097292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiedler B, Lohmann SM, Smolenski A, Linnemuller S, Pieske B, Schroder F, et al. Inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT hypertrophy signaling by cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11363–11368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162100799. doi:10.1073/pnas.162100799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lincoln TM, Komalavilas P, Boerth NJ, MacMillan-Crow LA, Cornwell TL. cGMP signaling through cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;34:305–322. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61094-7. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sausbier M, Schubert R, Voigt V, Hirneiss C, Pfeifer A, Korth M, et al. Mechanisms of NO/cGMP-dependent vasorelaxation. Circ Res. 2000;87:825–830. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.825. doi:10.1161/01.RES.87.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofmann F. The biology of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter U. Physiological role of cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase in the cardiovascular system. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;113:41–88. doi: 10.1007/BFb0032675. doi:10.1007/BFb0032675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orstavik S, Sandberg M, Bérubé D, Natarajan V, Simard J, Walter U, et al. Localization of the human gene for the type I cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase to chromosome 10. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1992;59:270–273. doi: 10.1159/000133267. doi:10.1159/000133267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butt E, Geiger J, Jarchau T, Lohmann SM, Walter U. The cGMP-dependent protein kinase: gene, protein, and function. Neurochem Res. 1993;18:27–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00966920. doi:10.1007/BF00966920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter U. Physiological role of cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase in cardiovascular system. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;113:42–88. doi: 10.1007/BFb0032675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandberg M, Natarajan V, Ronander I, Kalderon D, Walter U, Lohmann SM, et al. Molecular cloning and predicted full-legth amino acid sequence of the type IB isozyme of cGMP-dependent protein kinase from human placenta. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:321–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81114-7. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(89)81114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf L, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Characterization of a novel isozyme of cGMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine aorta. J Biol Chem. 1989;364:4157–4172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wernet W, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. The cDNA of the two isoforms of bovine cGMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine aorta. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81453-x. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(89)81453-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francis SH, Woodford TA, Wolfe L, Corbin JD. Types Ialpha and Ibeta isozymes of cGMP-dependent protein kinase: alternative mRNA splicing may produce different inhibitory domains. Second Messengers Phosphoproteins. 1989;12:301–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orstavik S, Natarajan V, Taskén K, Jahnsen T, Sandberg M. Characterization of the human gene encoding the type Iα and type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PRKG1) Genomics. 1997;42:311–318. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4743. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sellak H, Yang X, Cao X, Cornwell T, Soff GA, Lincoln TM. Sp1 transcription factor as a molecular target for nitric oxide- and cyclic nucleotide-mediated suppression of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-Iα expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2002;90:405–412. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105898. doi:10.1161/hh0402.105898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sellak H, Choi CS, Browner N, Lincoln TM. Upstream stimulatory factors (USF-1/USF-2) regulate human cGMP-dependent protein kinase I gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18425–18433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500775200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng Y, Zhuang S, Gloddek J, Tseng CC, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase expression by Rho and Kruppel-like transcription factor-4. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16951–16961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602099200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M602099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koutsodontis G, Moustakas A, Kardassis D. The role of Sp1 family members, the proximal GC-rich motifs and the upstream enhancer region in the regulation of the human cell cycle inhibitor p21WAF-1/Cip1 gene promoter. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12771–12784. doi: 10.1021/bi026141q. doi:10.1021/bi026141q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ai W, Liu Y, Langlois M, Wang TC. Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) represses histidine decarboxylase gene expression through an upstream Sp1 site and downstream gastrin responsive elements. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8684–8693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308278200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hou Y, Ye RD, Browning DD. Activation of the small GTPase Rac1 by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sauzeau V, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Marionneau C, Loirand G, Pacaud P. RhoA expression is controlled by nitric oxide through cGMP-dependent protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9472–9480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212776200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawada N, Itoh H, Yamashita J, Doi K, Inoue M, Masatsugu K, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates and inactivates RhoA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:798–805. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4194. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bois PRJ, Brochard VF, Salin-Cantegrel AVA, Cleveland JL, Grosveld GC. FoxO1a–cyclic GMP-dependent kinase I interactions orchestrate myoblast fusion. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7645–7656. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7645-7656.2005. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.17.7645-7656.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X, Jiang Y, Wang Z, Liu G, Hutz RJ, Liu W, et al. Regulation of FoxO1 transcription factor by nitric oxide and cyclic GMP in cultured rat granulosa cells. Zoolog Sci. 2005;22:1339–1346. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.1339. doi:10.2108/zsj.22.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tedeschi A, Nguyen T, Steele SU, Feil S, Naumann U, Feil R, et al. The tumor suppressor p53 transcriptionally regulates PKG-I expression during neuronal maturation and is required for cGMP-dependent growth cone collapse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15155–15160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4416-09.2009. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4416-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Wu Q, Qiu P, Mirza A, McGuirk M, Kirschmeier P, et al. Analyses of p53 target genes in the human genome by bioinformatic and microarray approaches. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43604–43610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106570200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao J, Lin H, Luo X, Luo X, Wang Z. miR-605 joins p53 network to form a p53:miR-605:Mdm2 positive feedback loop in response to stress. EMBO J. 2011;30:524–532. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.347. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borgan C. Nitric oxide and the regulation of gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:66–75. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01900-0. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Birsoy K, Chen Z, Friedman J. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis by KLF4. Cell Metab. 2008;7:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee J-W, Chen H, Pullikotil P, Quon MJ. Protein kinase A-α directly phosphorylates FoxO1 in vascular endothelial cells to regulate expression of vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:6423–6432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180661. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.180661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sayasith K, Lussier JG, Sirois J. Role of upstream stimulatory factor phosphorylation in the regulation of the prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 promoter in granulosa cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28885–28893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413434200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang S, Wang W, Wesley R, Danner RL. A Sp1 binding site of the tumor necrosis factor α promoter functions as a nitric oxide response element. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33190–33193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33190. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.47.33190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casteel DE, Zhuang S, Gudi T, Tang J, Vuica M, Desiderio S, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase Iβ physically and functionally interacts with the transcriptional regulator TFII-I. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32003–32014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112332200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gudi T, Casteel DE, Vinson C, Boss GR, Pilz RB. NO activation of fos promoter elements requires nuclear translocation of G-kinase I and CREB phosphorylation but is independent of MAP kinase activation. Oncogene. 2000;19:6324–6333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204007. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He B, Weber GF. Phosphorylation of NF-κB proteins by cyclic GMP-dependent kinase. A noncanonical pathway to NF-κB activation. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2174–2185. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03574.x. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esteve L, Lutz P, Thiriet N, Revel M, Aunis D, Zwiller J. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase potentiates serotonin-induced Egr-1 binding activity in PC12 cells. Cell Signal. 2001;13:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00163-2. doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pilz R, Suhasini M, Idrissi S, Meinkoth JL, Boss GR. Nitric oxide and cGMP analogs activate transcription from AP-1-responsive promoters in mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1995;9:552–558. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.7.7737465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ross J. mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:423–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.423-450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sellak H, Lincoln TM, Choi CS. Stabilization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (PKG) expression in vascular smooth muscle cells: contribution of 3′UTR of its mRNA. J Biochem. 2011;149:433–441. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr003. doi:10.1093/jb/mvr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Browner NC, Sellak H, Lincoln TM. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase expression by inflammatory cytokines in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C88–C96. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00039.2004. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00039.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boerth NJ, Dey NB, Cornwell TL, Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. J Vasc Res. 1997;34:245–259. doi: 10.1159/000159231. doi:10.1159/000159231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee HW, Smith L, Pettit GR, Vinitsky A, Smith JB. Ubiquitination of protein kinase C-α and degradation by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20973–20976. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.35.20973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Richardson JM, Howard P, Massa JS, Maurer RA. Post-transcriptional regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity by cAMP in GH3 pituitary tumor cells. Evidence for increased degradation of catalytic subunit in the presence of cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13635–13640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dey NB, Busch JL, Francis SH, Corbin JD, Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP specifically suppresses Type 1α cGMP-dependent protein kinase expression by ubiquitination. Cell Signal. 2009;21:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.014. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Busch JL, Bessay EP, Francis SH, Corbin JD. A conserved serine juxtaposed to the pseudosubstrate site of type I cGMP-dependent protein kinase contributes strongly to autoinhibition and lower cGMP affinity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34048–34054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202761200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gao Y, Dhanakoti S, Trevino EM, Wang X, Sander FC, Portugal AD, et al. Role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in development of tolerance to nitric oxide in pulmonary veins of newborn lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L786–L792. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00314.2003. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00314.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramchandran R, Pilipenko E, Bach L, Raghavan A, Reddy SP, Raj JU. Hypoxic regulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent kinase by the ubiquitin conjugating system. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:323–330. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0165OC. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2011-0165OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith JA, Francis SH, Walsh KA, Kumar S, Corbin JD. Autophosphorylation of type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase increases basal catalytic activity and enhances allosteric activation by cGMP or cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20756–20762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20756. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.34.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Francis SH, Smith JA, Colbran JL, Grimes K, Walsh KA, Kumar S, et al. Arginine 75 in the pseudosubstrate sequence of type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase is critical for autoinhibition, although autophosphorylated serine 63 is outside this sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20748–20755. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.34.20748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Melichar VO, Behr-Roussel D, Zabel U, Uttenthal LO, Rodrigo J, Rupin A, et al. Reduced cGMP signaling associated with neointimal proliferation and vascular dysfunction in late-stage atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16671–16676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405509101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405509110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sinnaeve P, Chiche JD, Gillijns H, Van Pelt N, Wirthlin D, Van De Werf F, et al. Overexpression of a constitutively active protein kinase G mutant reduces neointima formation and in-stent restenosis. Circulation. 2002;105:2911–2916. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018169.59205.ca. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000018169.59205.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. doi:10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.deBois D, O'Brien ER. The intima soil for atherosclerosis and restenosis. Circ Res. 1995;77:445–465. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.445. doi:10.1161/01.RES.77.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chyu KY, Dimayuga P, Zhu J, Nilsson J, Kaul S, Shah PK, et al. Decreased neointimal thickening after arterial wall injury in inducible nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. Circ Res. 1999;85:1192–1198. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1192. doi:10.1161/01.RES.85.12.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Von der Leyen HE, Gibbons GH, Morishita R, Lewis NP, Zhang L, Nakajima M, et al. Gene therapy inhibiting neointimal vascular lesion: in vivo transfer of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1137–1141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1137. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beasley D, Cooper A. Constitutive expression of interleukin-1a precursor promotes human vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H901–H912. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H901. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taylor AM, McNamara CA. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell growth: targeting the final common pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1717–1720. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000094396.24766.DD. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000094396.24766.DD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anwar A, Zahid AA, Scheidegger KJ, Brink M, Delafontaine P. Tumor necrosis factor-α regulates insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 expression in vascular smooth muscle. Circulation. 2002;105:1220–1225. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105187. doi:10.1161/hc1002.105187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor MS, Okwuchukwuasanya C, Nicki C, Tegge W, Brayden JE, Dostmann WRG. Inhibition of cGMP-dependent protein kinase by the cell-permeable peptide DT-2 reveals a novel mechanism of vasoregulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1111. doi:10.1124/mol.65.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou Z, Sayed N, Pyriochou A, Roussos C, Fulton D, Beeves A, et al. Protein kinase G phosphorylates soluble guanylyl cyclase on serine 64 and inhibits its activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1803–1810. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165043. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.John TA, Ibe BO, Raj JU. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: involvement of protein kinase G 1β, serine 116 phosphorylation and lipid structures. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dou D, Zheng X, Qin X, Qi H, Liu L, Raj JU, et al. Role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in development of tolerance to nitroglycerine in porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:497–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707600. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhuang D, Balani P, Pu Q, Thakran S, Hassid A. Suppression of PKG by PDGF or nitric oxide in differentiated aortic smooth muscle cells: obligatory role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H57–H63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00225.2010. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00225.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Soff GA, Cornwell TL, Cundiff DL, Gately S, Lincoln TM. Smooth muscle cell expression of type I cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase is suppressed by continuous exposure to nitrovasodilators, theophylline, cyclic GMP, and cyclic AMP. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2580–2587. doi: 10.1172/JCI119801. doi:10.1172/JCI119801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jacob A, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Begum N. MKP-1 expression and stabilization and cGK Iα prevent diabetes-associated abnormalities in VSMC migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1077–C1086. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00477.2003. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00477.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li Y, Gao Y, Zeng D. Atorvastatin inhibits collar-induced intimal thickening of rat carotid artery: effect on C-type natriuretic peptide expression. Mol Med Report. 2012;5:675–679. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Anderson PG, Boerth NJ, Liu M, McNamara DB, Cornwell TL, Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP–dependent protein kinase expression in coronary arterial smooth muscle in response to balloon catheter injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2192–2197. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.10.2192. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.20.10.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Resnik E, Herron J, Keck M, Sukovich D, Linden B, Cornfield DN. Chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension selectively modifies pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L426–L433. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00281.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lin CS, Liu X, Tu R, Chow S, Lue TF. Age-related decrease of protein kinase G activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:244–248. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5567. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yamashita T, Kawashima S, Ohashi Y, Ozaki M, Rikitake Y, Inoue N, et al. Mechanisms of reduced nitric oxide/cGMP-mediated vasorelaxation in transgenic mice overexpressing endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension. 2000;36:97–102. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.1.97. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.36.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang S, Hypolite JA, Velez M, Changolkar A, Wein AJ, Chacko S, et al. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-1 activity in the corpus cavernosum smooth muscle of diabetic rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R950–R960. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00639.2003. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00639.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Perkins WJ, Warner D, Jones KA. Prolonged treatment of porcine pulmonary artery with nitric oxide decreases cGMP sensitivity and cGMP-dependent protein kinase specific activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L121–L129. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90318.2008. doi:10.1152/ajplung.90318.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bachiller PR, Nakanishi H, Roberts JD. Transforming growth factor-β modulates the expression of nitric oxide signaling enzymes in the injured developing lung and in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L324–L334. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00181.2009. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00181.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gao Y, Dhanakoti S, Trevino EM, Sander FC, Portugal AM, Raj JU. Effect of oxygen on cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated relaxation in ovine fetal pulmonary arteries and veins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L611–L618. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00411.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruetten H, Zabel U, Linz W, Schmidt HH. Downregulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase in young and aging spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1999;85:534–541. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.6.534. doi:10.1161/01.RES.85.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Y, Tong X, Maimaitiyiming H, Clemons K, Cao J-M, Wang S. Overexpression of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (PKG-I) attenuates ischemia-reperfusion-induced kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F561–F570. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00355.2011. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00355.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhou W, Dasgupta C, Negash S, Raj JU. Modulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in hypoxia: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1459–L1466. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00143.2006. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00143.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu S, Ma X, Gong M, Shi L, Lincoln T, Wang S. Glucose downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I expression in vascular smooth muscle cells involves NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:852–863. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.025. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang S, Li Y. Expression of constitutively active cGMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits glucose-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H2075–H2083. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00521.2009. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00521.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]